Alevism

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2024) |

| Alevism | |

|---|---|

| Alevilik | |

| |

| Scripture | Quran,Nahj al-Balagha,MakalatandBuyruks |

| Leader | Dede |

| Teachings of | [9] |

| Theology | Haqq–Muhammad–Ali |

| Region | Turkey |

| Language | Turkish,Azerbaijani,Kurdish,andZazaki[10] |

| Liturgy | Cem,Sama |

| Headquarters | Haji Bektash Veli Complex,Nevşehir,Turkey |

| Founder | Haji Bektash Veli |

| Origin | 13th-century Sulucakarahöyük |

| Part ofa serieson theAlevis Alevism |

|---|

|

|

Alevism(/æˈlɛvɪzəm/;Turkish:Alevilik;Kurdish:Elewîtî[11][failed verification]) is asyncretic[12]Islamictradition, whose adherents follow themysticalIslamic teachings ofHaji Bektash Veli,who taught the teachings of theTwelve Imams,whilst incorporating some traditions fromTengrism.[13]Differing fromSunni IslamandUsuliTwelver Shia Islam,Alevis have no binding religiousdogmas,and teachings are passed on by aspiritual leaderas withSufi orders.[14]They acknowledge thesix articles of faith of Islam,but may differ regarding their interpretation.[10]They have faced significant institutional stigma from the Ottoman and later Turkish state and academia, being described asheterodox[15]to contrast them with the "orthodox"Sunnimajority.

Originally one of many Sufi approaches within Sunni Islam, by the 16th century the order adopted some tenets of Shia Islam, including the following of ʿAlī and the Twelve Imams, as well as a variety of syncretic beliefs. The Alevis acquired political importance in the 15th century, when the order dominated theJanissaries.[16]

The term “Alevi-Bektashi” is currently a widely and frequently used expression in the religious discourse of Turkey as an umbrella term for the two religious groups of Alevism andBektashism.[17]Adherents of Alevism are found primarily in Turkey and estimates of the percentage of Turkey's population that are Alevi include between 4% and 25%.[10][18][19]

Beliefs

[edit]According to scholarSoner Çağaptay,Alevism is a "relatively unstructured interpretation of Islam".[20]Journalist Patrick Kingsley states that for some self-described Alevi, their religion is "simply acultural identity,rather than a form of worship ".[21]

The Alevi beliefs among Turkish Alevis and Kurdish Alevis diverge as Kurdish Alevis put more emphasis onPir Sultan Abdalthan Haji Bektash Veli, and Kurdish Alevism is rooted more innature veneration.[22][23]

God

[edit]In Alevicosmology,God is also calledAl-Haqq(the Truth)[24]or referred to asAllah.God created life, so the created world can reflect His Being.[25]Alevis believe in the unity ofAllah, Muhammad, and Ali,but this is not atrinitycomposed ofGodand the historical figures of Muhammad and Ali. Rather,Muhammad and Aliare representations of Allah's light (and not of Allah himself), being neither independent from God, nor separate characteristics of Him.[24]

In Alevi writings are many references tothe unity of Muhammad and Ali,such as:

Ali Muhammed'dir uh dur fah'ad, Muhammad Ali, ( "Ali is Muhammad, Muhammad is Ali" ) Gördüm birelmadır, el-Hamdû'liLlâh.( "I've seen an apple, all praise is for God" )[26]

Spirits and afterlife

[edit]Alevis believe in the immortality of the soul,[24]the literal existence of supernatural beings, includinggood angels(melekler) andbad angels(şeytanlar),[27]bad ones as encourager of human's evil desires (nefs), andjinn(cinler), as well as theevil eye.[28]

Angels feature in Alevi cosmogony. Although there is no fixed creation narrative among Alevis, it is generally accepted that God created five archangels, who have been invited to the chamber of God. Inside they found a light representing the light of Muhammad and Ali. A recount of the Quranic story, one of the archangels refused to prostrate before the light, arguing, that the light is a created body just like him and therefore inappropriate to worship. He remains at God's service, but rejects the final test and turns back to darkness. From this primordial decline, the devil's enmity towards Adam emerged. (The archangels constitute of the same four archangels as within orthodox Islam. The fifth archangel namelyAzazilfell from grace, thus not included among the canonical archangels apart from this story).[29]

Another story features the archangelGabriel(Cebrail), who is asked by God, who they are. Gabriel answers: "I am I and you are you". Gabriel gets punished for his haughty answer and is sent away, until Ali reveals a secret to him. When God asks him again, he answers: "You are the creator and I am your creation". Afterwards, Gabriel was accepted and introduced to Muhammad and Ali.[29]

Scriptures and prophets

[edit]Alevis acknowledge the four revealed scriptures also recognized in Islam: theTawrat(Torah), theZabur(Psalms), theInjil(Gospel), and theQuran.[30]Additionally, Alevis are not opposed to looking to other religious books outside the four major ones as sources for their beliefs including Hadiths, Nahjul Balagha and Buyruks. Alevism also acknowledges the Islamic prophet Mohammed. Unlike the vast majority of Muslims, Alevis do not regard interpretations of the Quran today as binding or infallible, since the true meaning the Quran is considered to be taken as a secret by Ali and must be taught by a teacher, who transmits the teachings of Ali (Buyruk) to his disciple.[31]

Twelve Imams

[edit]The Twelve Imams are part of another common Alevi belief. Each Imam represents a different aspect of the world. They are realized as twelve services orOn İki Hizmetwhich are performed by members of the Alevi community. Each Imam is believed to be a reflection ofAli ibn Abu Talib,the first Imam of the Shi'ites, and there are references to the "First Ali"(Birinci Ali),Imam Hasanthe "Second 'Ali"(İkinci Ali),and so on up to the "Twelfth 'Ali"(Onikinci Ali),Imam Mehdi.The Twelfth Imam is hidden and represents theMessianic Age.

Plurality

[edit]The plurality in nature is attributed to the infinite potential energy of Kull-i Nafs when it takes corporeal form as it descends into being from Allah. During the Cem ceremony, the cantor oraşıksings:

- "All of us alive or lifeless are from one, this is ineffable, Sultan.

- For to love and to fall in love has been my fate from time immemorial. "

This is sung as a reminder that the reason for creation is love, so that the followers may know themselves and each other and that they may love that which they know.

Creed and jurisprudence

[edit]

Sources differ on how important formal doctrine is among contemporary Alevi. According to scholar Russell Powell, there is a tradition of informal "Dede" courts within the Alevi society, but regarding Islamic jurisprudence orfiqhthere has been "little scholarship on Alevi influences" in it.[33]Alevismhas a unique belief system tracing back toKaysanitesandKhurramites.[34]

Practices

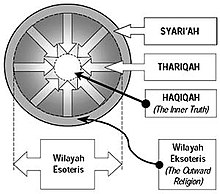

[edit]The Alevi spiritual path (yol) is commonly understood to take place through four major life-stages, or "gates". These may be further subdivided into "four gates,forty levels "(Dört Kapı Kırk Makam). The first gate (religious law) is considered elementary (and this may be perceived as subtle criticism of other Muslim traditions).

The following are major crimes that cause an Alevi to be declareddüşkün(shunned):[35]

- killing a person

- committing adultery

- divorcing one's wife without a just reason

- stealing

- backbiting/gossiping

Most Alevi activity takes place in the context of the second gate(spiritual brotherhood),during which one submits to a living spiritual guide(dede,pir,mürşid).The existence of the third and fourth gates is mostly theoretical, though some older Alevis have apparently received initiation into the third.[36]

Rakia,afruit brandy,is used as a sacramental element by theBektashi Order,[37]andAleviJemceremonies, where it is not considered alcoholic and is referred to as "dem".[38]

Dede

[edit]A Dede (literally meaning grandfather) is a traditional leader that is claimed to be from the lineage of Muhammad that performs ritual baptisms for newborns, officiates at funerals, and organises weekly gatherings at cemevis.[39]

Cem and Cemevi

[edit]

Alevi religious, cultural and other social activities take place in assembly houses (Cemevi). The ceremony's prototype is theMuhammad's nocturnal ascent into heaven,where he beheld a gathering of forty saints (Kırklar Meclisi), and the Divine Reality made manifest in their leader, Ali.

TheCemceremony features music, singing, and dancing (Samāh) in which both women and men participate. Rituals are performed inTurkish,Zazaki,Kurmanjiand other local languages.

- Bağlama

During theCem ceremonytheÂşıkplays theBağlamawhilst singing spiritual songs, some of which are centuries old and well known amongst Alevis. Every song, called aNefes,has spiritual meaning and aims to teach the participants important lessons.

- Samāh

A family of ritual dances characterized by turning and swirling, is an inseparable part of anycem.Samāhis performed by men and women together, to the accompaniment of theBağlama.The dances symbolize (for example) the revolution of the planets around the Sun (by man and woman turning in circles), and the putting off of one's self and uniting with God.

- Görgü Cemi

The Rite of Integration(görgü cemi)is a complex ritual occasion in which a variety of tasks are allotted to incumbents bound together by extrafamilial brotherhood (müsahiplik), who undertake a dramatization of unity and integration under the direction of the spiritual leader (dede).

- Dem

The love of the creator for the created and vice versa is symbolised in theCem ceremonyby the use of fruit juice and/or red wine[citation needed][Dem]which represents the intoxication of the lover in the beloved. During the ceremonyDemis one of the twelve duties of the participants. (see above)

- Sohbet

At the closing of the cem ceremony theDedewho leads the ceremony engages the participants in a discussion (chat), this discussion is called asohbet.

Twelve services

[edit]There are twelve services (Turkish:On İki hizmet) performed by the twelve ministers of the cem.

- Dede: This is the leader of the Cem who represents Muhammad and Ali. The Dede receives confession from the attendees at the beginning of the ceremony. He also leads funerals, Müsahiplik, marriage ceremonies and circumcisions. The status of Dede is hereditary and he must be a descendant of Ali and Fatima.

- Rehber: This position representsHusayn.The Rehber is a guide to the faithful and works closely with the Dede in the community.

- Gözcü: This position representsAbu Dharr al-Ghifari.S/he is the assistant to the Rehber. S/he is the Cem keeper responsible for keeping the faithful calm.

- Çerağcı: This position representsJabir ibn Abd-Allahand s/he is the light-keeper responsible for maintaining the light traditionally given by a lamp or candles.

- Zakir: This position representsBilal ibn al-Harith.S/he plays thebağlamaand recites songs and prayers.

- Süpürgeci: This position representsSalman the Persian.S/he is responsible for cleaning the Cemevi hall and symbolically sweeping the carpets during the Cem.

- Meydancı: This position representsHudhayfah ibn al-Yaman.

- Niyazcı: this position representsMuhammad ibn Maslamah.S/he is responsible for distributing the sacred meal.

- İbrikçi: this position represents Kamber. S/he is responsible for washing the hands of the attendees.

- Kapıcı: this position represents Ghulam Kaysan. S/he is responsible for calling the faithful to the Cem.

- Peyikçi: this position represents Amri Ayyari.

- Sakacı: representsAmmar ibn Yasir.Responsible for the distribution of water,sherbet(sharbat),milk etc..

Festivals

[edit]

Alevis celebrate and commemorate the birth of Ali, his wedding with Fatima, the rescue ofYusuffrom the well, and the creation of the world on this day. Various cem ceremonies and special programs are held.

Mourning of Muharram

[edit]The Muslim month ofMuharrambegins 20 days afterEid ul-Adha(Kurban Bayramı). Alevis observe a fast for the first twelve days, known as theMourning of Muharram(Turkish:Muharrem Mâtemi,Yâs-ı Muharrem,orMâtem Orucu;Kurdish:Rojîya ŞînêorRojîya Miherremê). This culminates in the festival ofAshura(Aşure), which commemorates the martyrdom ofHusaynatKarbala.The fast is broken with a special dish (also calledaşure) prepared from a variety (often twelve) of fruits, nuts, and grains. Many events are associated with this celebration, including the salvation of Husayn's sonAli ibn Husaynfrom the massacre at Karbala, thus allowing the bloodline of the family of Muhammad to continue.

Hıdırellez

[edit]

Hıdırellezhonors the mysterious figureKhidr(Turkish:Hızır) who is sometimes identified withElijah(Ilyas), and is said to have drunk of the water of life. Some hold that Khidr comes to the rescue of those in distress on land, while Elijah helps those at sea; and that they meet at a rose tree in the evening of every 6 May. The festival is also celebrated in parts of the Balkans by the name of "Erdelez," where it falls on the same day asGeorge's Day in SpringorSaint George's Day.

Khidr is also honored with a three-day fast in mid-February calledHızır Orucu.In addition to avoiding any sort of comfort or enjoyment, Alevis also abstain from food and water for the entire day, though they do drink liquids other than water during the evening.

Note that the dates of the Khidr holidays can differ among Alevis, most of whom use a lunar calendar, but some a solar calendar.

Müsahiplik

[edit]Müsahiplik(roughly, "Companionship" ) is a covenant relationship between two men of the same age, preferably along with their wives. In a ceremony in the presence of a dede the partners make a lifelong commitment to care for the spiritual, emotional, and physical needs of each other and their children. The ties between couples who have made this commitment is at least as strong as it is for blood relatives, so much so that müsahiplik is often called spiritual brotherhood(manevi kardeşlik).The children of covenanted couples may not marry.[40]

Krisztina Kehl-Bodrogi reports that theTahtacıidentifymüsahiplikwith the first gate(şeriat),since they regard it as a precondition for the second(tarikat).Those who attain to the third gate(marifat,"gnosis") must have been in amüsahiplikrelationship for at least twelve years. Entry into the third gate dissolves themüsahiplikrelationship (which otherwise persists unto death), in a ceremony calledÖz Verme Âyini( "ceremony of giving up the self" ).

The value corresponding to the second gate (and necessary to enter the third) isâşinalık( "intimacy," perhaps with God). Its counterpart for the third gate is calledpeşinelik;for the fourth gate(hâkikat,Ultimate Truth),cıngıldaşlıkorcengildeşlik(translations uncertain).[41]

Folk practices

[edit]Many folk practices may be identified, though few of them are specific to the Alevis. In this connection, scholar Martin van Bruinessen notes a sign from Turkey's Ministry of Religion, attached to Istanbul's shrine ofEyüp Sultan,which presents

...a long list of ‘superstitious’ practices that are emphatically declared to be non-Islamic and objectionable, such as lighting candles or placing ‘wishing stones’ on the tomb, tying pieces of cloth to the shrine or to the trees in front of it, throwing money on the tomb, asking the dead directly for help, circling seven times around the trees in the courtyard or pressing one’s face against the walls of the türbe in the hope of a supernatural cure, tying beads to the shrine and expecting supernatural support from them, sacrificing roosters or turkeys as a vow to the shrine. The list is probably an inventory of common local practices the authorities wish to prevent from re-emerging.[42]

Other, similar practices include kissing door frames of holy rooms; not stepping on the threshold of holy buildings; seeking prayers from reputed healers; and makinglokmaand sharing it with others. Also,Ashureis made and shared with friends and family during the month ofMuharramin which theDay of Ashuretakes place.[43]

Ziyarat to sacred places

[edit]Performingziyaratanddu'aat the tombs of Alevi-Bektashi saints orpirsis quite common. Some of the most frequently visited sites are the shrines ofŞahkuluandKaracaahmet(both inIstanbul), Abdal Musa (Antalya),Seyyid Battal Gazi Complex(Eskişehir), Hamza Baba (İzmir), Hasandede (Kırıkkale).[44]

In contrast with the traditional secrecy of theCem ceremonyritual, the events at these cultural centers and sites are open to the public. In the case of theHacibektaş celebration,since 1990 the activities there have been taken over by Turkey's Ministry of Culture in the interest of promoting tourism and Turkish patriotism rather than Alevi spirituality. The annual celebrations held atHacıbektaş(16 August)andSivas(thePir SultanAbdalKültür Etkinlikleri, 23–24 June).

Some Alevis make pilgrimages to mountains and other natural sites believed to be imbued with holiness.

Almsgiving

[edit]Alevis are expected to givezakat,but there is noset formula or prescribed amountfor annual charitable donation as there is in other forms of Islam (2.5% of possessions above a certain minimum). Rather, they are expected to give the "excess" according to Qur'an 2:219. A common method of Alevi almsgiving is through donating food (especially sacrificial animals) to be shared with worshippers and guests. Alevis also donate money to be used to help the poor, to support the religious, educational and cultural activities of Alevi centers and organizations (dargahs,awqaf,and meetings), and to provide scholarships for students.

History

[edit]

Seljuk period

[edit]During the great Turkish expansion from Central Asia into Iran and Anatolia in the Seljuk period (11–12th centuries), Turkmen and Kurdish nomad tribes accepted a Sufi and pro-Ali form of Islam that co-existed with some of their pre-Islamic customs. Their conversion to Islam in this period was achieved largely through the efforts not of textual scholars (ulema) expounding the finer points of Koranic exegesis and shari‘a law, but by charismaticSufidervishes a belief whose cult of Muslim saint worship, mystical divination andmillenarianismspoke more directly to the steppe mindset. These tribes dominated Anatolia for centuries with their religious warriors (ghazi) spearheading the drive against Byzantines and Crusaders.[45][page needed][verification needed]

Ottoman period

[edit]As in Khorasan and West Asia before, the Turkmens who spearheaded the Ottomans’ drive into the Balkans and West Asia were more inspired by a vaguely Shiite folk Islam than by formal religion. Many times, Ottoman campaigns were accompanied or guided by Bektaşi dervishes, spiritual heirs of the 13th century Sufi saintHaji Bektash Veli,himself a native ofKhorasan.After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottoman state became increasingly determined to assert its fiscal but also its juridical and political control over the farthest reaches of the Empire.[45]

The resulting Alevi revolts, a series of millenarian anti-state uprisings by the non-SunniTurkmenpopulation of Anatolia that culminated in the establishment of a militantly Shiite rival state in neighbouring Iran.[45]The Ottoman Empire later proclaimed themselves its defenders against theSafavid Shia stateand related sects. This created a gap between the Sunni Ottoman ruling elite and the Alevi Anatolian population. Anatolia became a battlefield between Safavids and Ottomans, each determined to include it in their empire.

Republic of Turkey

[edit]According to Eren Sarı, Alevi saw Kemal Atatürk as aMahdi"savior sent to save them from the Sunni Ottoman yoke".[46]However, pogroms against Alevi did not cease after the establishment of the Turkish Republic. In attacks against leftists in the 1970s, ultranationalists and reactionaries killed many Alevis.Malatya in 1978,Maraş in 1979,andÇorum in 1980witnessed the murder of hundreds of Alevis, the torching of hundreds of homes, and lootings.[47][48]

Alevis have been victims ofpogromsduring both Ottoman times and under the Turkish republic up until the1993 Sivas massacre.[21][47][48]

Organization

[edit]| Part ofa seriesonIslam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

In contrast to theBektashi order–tariqa,which like other Sufi orders is based on asilsila"initiatory chain or lineage" of teachers and their students, Alevi leaders succeed to their role on the basis of family descent. Perhaps ten percent of Alevis belong to a religious elite calledocak"hearth", indicating descent from Ali and/or various other saints and heroes.Ocakmembers are calledocakzades or "sons of the hearth". This system apparently originated in the Safavid state.

Alevi leaders are variously calledmurshid,pir,rehberordede.Groups that conceive of these as ranks of a hierarchy (as in theBektashi Order) disagree as to the order. The last of these,dede"grandfather", is the term preferred by the scholarly literature.Ocakzades may attain to the position ofdedeon the basis of selection (by a father from among several sons), character, and learning. In contrast to Alevi rhetoric on the equality of the sexes, it is generally assumed that only males may fill such leadership roles.

Traditionally,dedesdid not merely lead rituals, but led their communities, often in conjunction with local notables such as theağas(large landowners) of theDersim Region.They also acted as judges or arbiters, presiding over village courts calledDüşkünlük Meydanı.

Ordinary Alevi would owe allegiance to a particulardedelineage (but not others) on the basis of pre-existing family or village relations. Some fall instead under the authority of Bektashi dargahs.

In the wake of 20th century urbanization (which removed young laborers from the villages) and socialist influence (which looked upon the dedes with suspicion), the old hierarchy has largely broken down. Many dedes now receive salaries from Alevi cultural centers, which arguably subordinates their role. Such centers no longer feature community business or deliberation, such as the old ritual of reconciliation, but emphasize musical and dance performance to the exclusion of these.[49]Dedes are now approached on a voluntary basis, and their role has become more circumscribed – limited to religious rituals, research, and giving advice.

According to John Shindeldecker "Alevis are proud to point out that they aremonogamous,Alevi women are encouraged to get the best education they can, and Alevi women are free to go into any occupation they choose. "[50]

Relationship with Shia Islam

[edit]Alevis are classified as a sect of Shia Islam,[51]and AyatollahRuhollah Khomeinidecreed Alevis to be part of the Shia fold in the 1970s.[52]However, Alevi philosophies, customs, and rituals are appreciably different from those of mainstream, orthodoxUsulis.According to Alevis[which?],Ali and Muhammad are likened to the two sides of a coin, or the two halves of an apple.[citation needed]

Relationship with Alawites

[edit]Similarities with theAlawitesofSyriaexist.[citation needed]Both are viewed asheterodox[citation needed],syncreticIslamic minorities, whose names both mean "devoted toAli,"(the son-in-law and cousin of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, and fourthcaliphfollowing Muhammad as leader of the Muslims), and are located primarily in the Eastern Mediterranean. Like mainstream Shia they are known as "Twelvers" as they both recognize the Twelve Imams.

How the two minorities relate is disputed. According to scholar Marianne Aringberg-Laanatza, "the Turkish Alevis... do not relate themselves in any way to the Alawites in Syria."[53]However journalistJeffrey Gettlemandclaims that both Alevi and the less than one million Alawite minority in Turkey "seem to be solidly behind Syria’s embattled strongman,Bashar al-Assad"and leery of Syrian Sunni rebels.[54]Deutsche Wellejournalist Dorian Jones states that Turkish Alevis are suspicious of the anti-Assad uprising in Syria. "They are worried of the repercussions for Alawites there, as well as for themselves."[55]

Some sources (Martin van Bruinessen and Jamal Shah) mistake Alawites living in Turkey to be Alevis (calling Alevis "a blanket term for a large number of different heterodox communities" ),[56]but others do not, giving a list of the differences between the two groups. These include their liturgical languages (Turkish or Kurdish for Alevi, Arabic for Alawites). Opposing political nationalism, with Alawites supporting their ruling dictatorship and considering Turks (including Alevis) an "opponent" of its Arab "historic interests".[citation needed](Even Kurdish and Balkan Alevi populations pray in Turkish.)[20]

Unlike Alevis, Alawites not only traditionally lack mosques but do not maintain their own places for worship, except for shrines to their leaders.[citation needed]Alevi "possess an extensive and widely-read religious literature, mainly composed of spiritual songs, poems, and epic verse." Their origins are also different: The Alawite faith was founded in the ninth century by Abu Shuayb Muhammadibn Nusayr.Alevism started in the 14th century by mystical Islamic dissenters in Central Asia, and represent more of a movement rather than a sect.

Relationship with Sunnis

[edit]The relationship between Alevis and Sunnis is one of mutual suspicion and prejudice dating back to the Ottoman period. Hundreds of Alevis were murdered in sectarian violence in the years that preceded the1980 coup,and as late as the 1990s dozens were killed with impunity.[21]While pogroms have not occurred since then, Erdogan has declared "acemeviis not a place of worship, it is a center for cultural activities. Muslims should only have one place of worship. "[21]

Alevis[which?]claim that they have been subject tointolerantSunni "nationalism" that has been unwilling to recognize Alevi "uniqueness".[57]

Demographics

[edit]

Most Alevi live in Turkey, where they are a minority and Sunni Muslims the majority. The size of the Alevi population is likewise disputed, but most estimates place them somewhere between 5 and 10 million people or about 10% of the population.[58][59]Estimates of the percentage of Turkey's population that are Alevi range between 4% and 15%.[10][18]Scattered minorities live in theBalkans,the Caucasus,Cyprus,Greece,Iranand the diaspora such as Germany and France.[60]In the2021 United Kingdom census,Alevism was discovered to be the eighth largest religion in England and Wales, after Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism, Judaism and Paganism.[61]

Different estimations exist on the ethnic composition of the Alevi population. Although Turks are probably the largest ethnic group among Alevis considering their historical towns and cities.[citation needed]While Dressler stated in 2008 that about a third of the Alevi population is Kurdish,[23]Hamza Aksüt argued that the majority is Kurdish[62]when all groups he considers as Alevis, such as theYarsanis,[63]are counted.[64]

Most Alevis are probably of Kizilbash or Bektashi origin.[10]The Alevis (Kizilbash) are traditionally predominantly rural and acquire identity by parentage. Bektashis, however, are predominantly urban, and formally claim that membership is open to any Muslim. The groups are separately organized, but subscribe to "virtually the same system of beliefs".[10]

Population estimates

[edit]The Alevi population has been estimated as follows:

- Approximately 20 million according toDaily Sabah,a newspaper close to the government in 2021.[65]

- 12,521,000 according toSabahat Akkiraz,an MP fromCHP.[66]

- "approx. 15 million..." – Krisztina Kehl-Bodrogi.[67]

- 4% of total population of Turkey –KONDA Research(2021).[18]

- In Turkey, 15% of Turkey's population (approx. 10.6 million) – Shankland (2006).[68]

- 20 to 25 million according to Minority Rights Group.[10]

- There is a native 3,000 Alevi community inWestern Thrace,Greece.[69]

- The predominant religion of theÄynu peopleof western China is Alevism.[70][71][72]There are estimated to be around 30–50 thousand Äynu, mostly located on the fringe of theTaklamakan Desert.[73][74]

- 25,672 Alevi live in England and Wales.[61]

- 600k to 700k Alevi live in Germany.[75][76]

- 100k to 200k Alevi live in France.[77][78]

Social groups

[edit]

A Turkish scholar working in France has distinguished four main groups among contemporary Alevis in Turkey.[79]

The first group, who form a majority of the Alevi population, regard themselves as true Muslims and are prepared to cooperate with the state. It adheres to the way ofJafar as-Sadiq,the Sixth Imam of Shia Islam. This group's concept ofGodis the same as Orthodox Islam, and like their Shia counterparts they reject the first three chosenCaliphs,whom Sunni accept as legitimate, and accept onlyAlias the actual and true Caliph.[79]

The second group, which has the second most following among Alevis, are said to be under the active influence of the official Iranian Shia and to be confirmed adherents of theTwelverbranch of Shia Islam and they reject the teachings of Bektashism Tariqa. They follow theJa'fari jurisprudenceand oppose secular state power.[79]

The third group, a minority belief held by the Alevis, is mainly represented by people who belong to the political left and presumedthe Alevinessas an outlook on life rather than a religious conviction by renouncing the ties of Alevism with Twelver Shia Islam. The followers of this congregation, who later turned out to supportErdoğan Çınar,hold ritual unions of a religious character and have established cultural associations named afterPir Sultan Abdalas well. According to their philosophy, the human being should enjoy a central role reminiscent of the doctrine ofKhurramites,and as illustrated byHurufiphrase ofGod is Manquoted above in the context of theTrinity.[79]

The fourth[citation needed]who adopted some aspirations ofChristian mysticism,is more directed towards heterodoxmysticismand stands closer to theHajji BektashiBrotherhood. According to the philosophy developed by this congregation,ChristianmysticSt Francis of AssisiandHinduMahatma Gandhiare better believers ofGodthan manyMuslims.[79]

Influences of other beliefs and sects on Alevism

[edit]| Part ofa serieson the Bektashi Order |

|---|

|

Sufi elements in Alevism

[edit]Despite this essentially Shi‘i orientation, much of Aleviness' mystical language is inspired by Sufi traditions. For example, the Alevi concept of God is derived from the philosophy ofIbn Arabiand involves a chain ofemanationfrom God, to spiritual man, earthly man, animals, plants, and minerals. The goal of spiritual life is to follow this path in the reverse direction, to unity with God, oral-Haqq(Reality, Truth). From the highest perspective, all is God (seeSufi metaphysics). Alevis admireal-Hallaj,a 10th-century Sufi who was accused of blasphemy and subsequently executed inBaghdadfor saying "I am the Truth"(Ana al-Haqq).

There is some tension between folk tradition Aleviness and the Bektashi Order, which is a Sufi order founded on Alevi beliefs.[80]In certain Turkish communities other Sufi orders (theHalveti-Jerrahiand some of theRifaʽi) have incorporated significant Alevi influence.

Wahdat al-Mawjud

[edit]Bektashism places much emphasis on the concept ofWahdat al-Mawjudوحدة الوجود, the "Unity of Being" that was formulated byIbn Arabi.Bektashism is also heavily permeated with Shiite concepts, such as the marked veneration of Ali, the Twelve Imams, and the ritual commemoration ofAshurahmarking the Battle of Karbala. The oldPersianholiday ofNowruzis celebrated by Bektashis asImamAli's birthday.

In keeping with the central belief ofWahdat Al-Mawjudthe Bektashi see reality contained inHaqq-Muhammad-Ali,a single unified entity. Bektashi do not consider this a form oftrinity.There are many other practices and ceremonies that share similarity with other faiths, such as a ritual meal (muhabbet) and yearly confession of sins to ababa(magfirat-i zunubمغفرة الذنوب).

Bektashis base their practices and rituals on their non-orthodox andmystical interpretationand understanding of theQur'anand the prophetic practice (Sunnah). They have no written doctrine specific to them, thus rules and rituals may differ depending on under whose influence one has been taught. Bektashis generally revere Sufi mystics outside of their own order, such asIbn Arabi,Al-GhazaliandJelalludin Rumiwho are close in spirit to them.

Mysticism

[edit]Bektashism isinitiaticand members must traverse various levels or ranks as they progress along the spiritual path to theReality.First level members are calledaşıksعاشق. They are those who, while not having taken initiation into the order, are nevertheless drawn to it. Following initiation (callednasip) one becomes amühipمحب. After some time as amühip,one can take further vows and become adervish.

The next level above dervish is that ofbaba.Thebaba(lit. father) is considered to be the head of atekkeand qualified to give spiritual guidance (irshadإرشاد). Above thebabais the rank ofhalife-baba(ordede,grandfather). Traditionally there were twelve of these, the most senior being the "dedebaba"(great-grandfather).

Thededebabawas considered to be the highest ranking authority in the Bektashi Order. Traditionally the residence of thededebabawas the Pir Evi (The Saint's Home) which was located in the shrine ofHajji Bektash Waliin the central Anatolian town ofHacıbektaş(Solucakarahüyük).

Non-Islamic elements

[edit]Alevism is indeed heavily influenced by oldTurkicandshamanisticbeliefs. Concepts such asOdjak,inclusive social roles for women, musical performances, various rituals celebrating the nature or the seasons (likeHıdırellez) and some customs like the cult of ancestors, trees and rocks are both observed in Alevism andTengrism.[81][82]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abMarkussen, Hege Irene (2010)."Alevi Theology from Shamanism to Humanism".Alevis and Alevism.pp. 65–90.doi:10.31826/9781463225728-006.ISBN978-1-4632-2572-8.

- ^Procházka-Eisl, Gisela (5 April 2016)."The Alevis".Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion.doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.101.ISBN978-0-19-934037-8.Retrieved14 April2023.

- ^"Alevism-Bektashism From Seljuks to Ottomans and Safavids; A Historical Study".Retrieved14 April2023.

- ^Yildirim, Riza (2019)."The Safavid-Qizilbash Ecumene and the Formation of the Qizilbash-Alevi Community in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1500–c. 1700".Iranian Studies.52(3–4): 449–483.doi:10.1080/00210862.2019.1646120.S2CID204476564.Retrieved14 April2023– via academia.edu.

- ^Mete, Levent (2019)."Buyruk und al Jafr Das Esoterische Wissen Alis"[Buyruk and al Jafr The esoteric knowledge of Ali].Alevilik-Bektaşilik Araştırmaları Dergisi: Forschungszeitschrift über das Alevitentum und das Bektaschitentum[Alevilik-Bektaşilik Araştırmaları Dergisi: Research journal on Alevism and Bektashism] (in German).19:313–350.Retrieved9 January2024.

- ^Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer (2019). "5 Mysticism and Imperial Politics: The Safavids and the Making of the Kizilbash Milieu".The Kizilbash-Alevis in Ottoman Anatolia: Sufism, Politics and Community.Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 220–255.doi:10.1515/9781474432702-012.ISBN9781474432702.

- ^Karolewski, Janina (2021). "Adaptation of Buyruk Manuscripts to Impart Alevi Teachings: Mehmet Yaman Dede and the Arapgir-Çimen Buyruğu".Education Materialised.pp. 465–496.doi:10.1515/9783110741124-023.ISBN9783110741124.S2CID237904256.

- ^Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer (2010). "Documents and" Buyruk "Manuscripts in the Private Archives of Alevi Dede Families: An Overview".British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies.37(3): 273–286.doi:10.1080/13530194.2010.524437.JSTOR23077031.S2CID161466774.

- ^[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

- ^abcdefg"Alevis".World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples.Minority Rights Group.19 June 2015.Retrieved14 April2023.

- ^Gültekin, Ahmet Kerim (2019),Kurdish Alevism: Creating New Ways of Practicing the Religion(PDF),University of Leipzig,p. 10

- ^Selmanpakoğlu, Ceren (11 February 2024).The formation of Alevi syncretism(Thesis). Bilkent University.

- ^Markussen, Hege Irene (2010)."Alevi Theology from Shamanism to Humanism".Alevis and Alevism.pp. 65–90.doi:10.31826/9781463225728-006.ISBN978-1-4632-2572-8.

- ^Tee, Caroline (29 January 2013)."The Sufi Mystical Idiom in Alevi Aşık Poetry: Flexibility, Adaptation and Meaning".European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey.doi:10.4000/ejts.4683.ISSN1773-0546.

- ^Karolewski, Janina (2008)."What is Heterodox About Alevism? The Development of Anti-Alevi Discrimination and Resentment".Die Welt des Islams.48(3/4): 434–456.doi:10.1163/157006008X364767.ISSN0043-2539.JSTOR27798275.

- ^"Bektashiyyah | Religion, Order, Beliefs, & Community | Britannica".

- ^"The Amalgamation of Two Religious Cultures: The Conceptual and Social History of Alevi-Bektashism".12 May 2022.

- ^abc"TR100".interaktif.konda.tr.Retrieved13 October2022.

- ^Kızıl, Nurbanu (31 December 2021)."Govt signals action for Turkey's Alevi community amid obstacles".Daily Sabah.Retrieved12 March2023.

- ^abCagaptay, Soner (17 April 2012)."Are Syrian Alawites and Turkish Alevis the same?".CNN.Archived fromthe originalon 7 January 2022.Retrieved28 July2017.

- ^abcdKINGSLEY, PATRICK (22 July 2017)."Turkey's Alevis, a Muslim Minority, Fear a Policy of Denying Their Existence".The New York Times.New York Times.Retrieved27 July2017.

- ^Wakamatsu, Hiroki (2013). "Veneration of the Sacred or Regeneration of the Religious: An Analysis of Saints and the Popular Beliefs of Kurdish Alevis".Thượng trí アジア học.31.Sophia University:12.

- ^abDressler, Markus (2008)."Alevīs".In Fleet, Kate;Krämer, Gudrun;Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John;Rowson, Everett(eds.).Encyclopaedia of Islam(3rd ed.). Brill Online.ISSN1873-9830.

- ^abcHande SözerManaging Invisibility: Dissimulation and Identity Maintenance among Alevi Bulgarian TurksBRILL 2014ISBN978-9-004-27919-3page 114

- ^Tord Olsson, Elisabeth Ozdalga, Catharina RaudvereAlevi Identity: Cultural, Religious and Social PerspectivesTord Olsson, Elisabeth Ozdalga, Catharina RaudvereISBN978-1-135-79725-6page 25

- ^These and many other quotations may be found inJohn Shindeldecker (1998).Turkish Alevis Today.Sahkulu Sultan Külliyesi Vakfı.ISBN9789759444105.OCLC1055857045.

- ^Özbakir, Akin. Malatya Kale yöresi Alevi-Bektaşi inançlarının tespit ve değerlendirilmesi. MS thesis. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, 2010.

- ^Aksu, İbrahim."Differences & Similarities Between Anatolian Alevis & Arab Alawites: Comparative Study on Beliefs and Practices".academia.edu.

- ^abAlevi Hafızasını Tanımlamak: Geçmiş ve Tarih Arasında. (2016). (n.p.): İletişim Yayınları.

- ^Tord Olsson, Elisabeth Ozdalga, Catharina RaudvereAlevi Identity: Cultural, Religious and Social PerspectivesTord Olsson, Elisabeth Ozdalga, Catharina RaudvereISBN978-1-135-79725-6page 72

- ^Handan Aksünger Jenseits des Schweigegebots: Alevitische Migrantenselbstorganisationen und zivilgesellschaftliche Integration in Deutschland und den Niederlanden Waxmann Verlag 2013ISBN978-3-830-97883-1page 83-84 (German)

- ^Darke, Diana (2022).The Ottomans: A Cultural Legacy.Thames & Hudson. pp. 86, 88.ISBN978-0-500-77753-4.

- ^Powell, Russell (2016).Shariʿa in the Secular State: Evolving Meanings of Islamic Jurisprudence in.Routledge. p. 35.ISBN9781317055693.Retrieved27 July2017.

- ^Roger M. Savory (ref. Abdülbaki Gölpinarli),Encyclopaedia of Islam,"Kizil-Bash", Online Edition 2005

- ^Also see, Öztürk, ibid, pp. 78–81. In the old days, marrying a Sunni [Yezide kuşak çözmek] was also accepted as an offense that led to the state of düşkün. See Alevi Buyruks

- ^Kristina Kehl-Bordrogi reports this among theTahtacı.See her article "The significance ofmüsahiplikamong the Alevis "inSynchronistic Religious Communities in the Near East(co-edited by her, with B. Kellner-Heinkele & A. Otter-Beaujean), Brill 1997, p. 131 ff.

- ^Magra, Iliana (26 November 2023)."The Bektashis have stopped hiding".Ekathimerini.Archived fromthe originalon 30 November 2023.

- ^Soileau, Mark (August 2012)."Spreading theSofra:Sharing and Partaking in the Bektashi Ritual Meal ".History of Religions.52(1): 1–30.doi:10.1086/665961.JSTOR10.1086/665961.Retrieved5 June2021.

- ^Farooq, Umar."Turkey's Alevis beholden to politics".aljazeera.

- ^Krisztina Kehl-Bodrogi. 1988. Die Kizilbash/Aleviten, pp. 182–204.

- ^See again "The significance ofmüsahiplikamong the Alevis "inSynchronistic Religious Communities in the Near East(co-edited by her, with B. Kellner-Heinkele & A. Otter-Beaujean), Brill 1997, p. 131 ff.

- ^Religious practices in the Turco-Iranian World,2005.

- ^Fieldhouse, P. (2017).Food, Feasts, and Faith: An Encyclopedia of Food Culture in World Religions [2 volumes].ABC-CLIO. p. 42.ISBN978-1-61069-412-4.Retrieved11 August2017.

- ^"ALEVİ & BEKTAŞİLERİN KUTSAL YERLERİ-TÜRBELER haberleri".

- ^abcشيعه_لبنان_زير_سلطه_عثمانيebookshia (in Arabic)

- ^Sarı, Eren (2017).The Alevi Of Anatolia: During the great Turkish expansion from Central Asia.noktaekitap. p. 16.Retrieved27 July2017.

- ^ab"Pir Sultan Abdal Monument and Festival".memorializeturkey.Archived fromthe originalon 14 July 2014.Retrieved27 June2014.

- ^abRana Birden Çorbacıoğlu, Zeynep Alemdar."ALEVIS AND THE TURKISH STATE"(PDF).turkishpolicy.Retrieved27 June2014.

- ^See Martin Stokes' study.

- ^Flows, Capital."Religious Diversity And The Alevi Struggle For Equality In Turkey".Forbes.Retrieved1 January2020.

- ^Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009)."Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population, Pew Research Center"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 10 October 2009.Retrieved8 October2009.

- ^Nasr, V: "The Shia Revival," page 1. Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc, 2006

- ^{ Aringberg-Laanatza, Marianne.“Alevis in Turkey–Alawites in Syria: Similarities and Differences.” In Alevi Identity: Cultural, Religious and Social Perspectives.Edited by Tord Olsson, Elisabeth Özdalga, and Catharina Raudvere, 181–199. Richmond, UK: Curzon, 1998.}

- ^Gettleman, Jeffrey (4 August 2012)."Turkish Alawites Fear Spillover of Violence From Syria".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved28 July2017.

- ^Jones, Dorian (22 March 2012)."Alevi Turks concerned for Alawi 'cousins' in Syria | Globalization | DW |".Deutsche Welle.Deutsche Welle.Retrieved28 July2017.

- ^van Bruinessen, Martin (c. 1995)."Kurds, Turks, and the Alevi Revival in Turkey".islam.uga.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 12 May 2014.Retrieved31 July2017.

- ^Karin Vorhoff. 1995. Zwischen Glaube, Nation und neuer Gemeinschaft: Alevitische Identitat in der Türkei der Gegenwart, pp. 95–96.

- ^"Turkey: International Religious Freedom Report 2007".State.gov. 14 September 2007.Retrieved9 August2011.

- ^Daan Bauwens (18 February 2010)."Turkey's Alevi strive for recognition".Asia Times Online.Archived fromthe originalon 22 February 2010.Retrieved9 August2011.

- ^Massicard, Elise (12 October 2012).The Alevis in Turkey and Europe: Identity and Managing Territorial Diversity.Routledge.ISBN9781136277986.Retrieved5 June2014– via googlebooks.

- ^ab"Religion, England and Wales".Office of National Statistics.Retrieved30 November2022.

- ^Gezik, Erdal (2021). "The Kurdish Alevis: The Followers of the Path of Truth". In Bozarslan, Hamit (ed.).The Cambridge History of the Kurds.Cambridge University Press.p. 562.doi:10.1017/9781108623711.026.S2CID235541104.

- ^Aksüt, Hamza (2009).Aleviler: Türkiye, İran, İrak, Suriye, Bulgaristan: araştırma-inceleme.Yurt Kitap-Yayın. p. 319.ISBN9789759025618.Retrieved31 July2022.

- ^Hamza Aksüt.Hamza Aksüt ile Alevi Ocakları Üzerine - Aleviliğin Kökleri(in Turkish).Retrieved1 August2022.

- ^"Govt signals action for Turkey's Alevi community amid obstacles".dailysabah.31 December 2021.Retrieved9 March2022.

- ^"Sabahat Akkiraz'dan Alevi raporu".haber.sol.org.tr.14 December 2012.Retrieved25 June2014.

- ^From the introduction ofSyncretistic Religious Communities in the Near Eastedited by her, B. Kellner-Heinkele, & A. Otter-Beaujean. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

- ^Structure and Function in Turkish Society.Isis Press, 2006, p. 81.

- ^Μποζανίνου Τάνια (23 January 2011)."ΤΟ ΒΗΜΑ – Αλεβίτες, οι άγνωστοι" συγγενείς "μας – κόσμος".Tovima.gr.Retrieved22 November2012.

- ^Louie, Kam (2008).The Cambridge Companion to Modern Chinese Culture.Cambridge University Press.p. 114.ISBN978-0521863223.

- ^Starr, S. Frederick (2004).Xin gian g: China's Muslim Borderland: China's Muslim Borderland.Routledge.p. 303.ISBN978-0765613189.

- ^Bader, Alyssa Christine (9 May 2012)."Mummy dearest: questions of identity in modern and ancient Xin gian g Uyghur Autonomous Region".Alyssa Christine BaderWhitman Collegep31.Retrieved19 November2020.

- ^Johanson, Lars (2001)."Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map"(PDF).Stockholm: Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul. pp. 21–22.

- ^Minahan, James B. (2014).Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO. pp. 14–15.ISBN9781610690188.

- ^"Alevitische Gemeinde".Stadt Kassel.

- ^"Aleviten in Deutschland".16 September 2021.

- ^Yaman, Ali; Dönmez, Rasim Özgür (2016)."Creating cohesion from diversity through mobilization: Locating the place of Alevi federations in Alevi collective identity in Europe".Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi(77). Ankara Hacı Bayram Veli University: 13–36.

- ^Koşulu, Deniz (2013). "The Alevi quest in Europe through the redefinition of the Alevi movement: recognition and political participation, a case study of the Fuaf in France".Muslim Political Participation in Europe.Edinburgh University Press. pp. 255–276.doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748646944.003.0013.ISBN978-0-7486-4694-4.

- ^abcdeBilici, F: "The Function of Alevi-Bektashi Theology in Modern Turkey", seminar. Swedish Research Institute, 1996

- ^Ataseven, I: "The Alevi-Bektasi Legacy: Problems of Acquisition and Explanation", page 1. Coronet Books Inc, 1997

- ^"The formation of Alevi syncretism".

- ^Dressler, Markus."The Discovery of the Alevis' Shamanism and the Need for Scholarly Accuracy".

Bibliography

[edit]- General introductions

- Dressler, Markus (2008)."Alevīs".In Fleet, Kate;Krämer, Gudrun;Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John;Rowson, Everett(eds.).Encyclopaedia of Islam(3rd ed.). Brill Online.ISSN1873-9830.

- Engin, Ismail & Franz, Erhard (2000).Aleviler / Alewiten. Cilt 1 Band: Kimlik ve Tarih / Identität und Geschichte.Hamburg: Deutsches Orient Institut (Mitteilungen Band 59/2000).ISBN3-89173-059-4

- Engin, Ismail & Franz, Erhard (2001).Aleviler / Alewiten. Cilt 2 Band: İnanç ve Gelenekler / Glaube und Traditionen.Hamburg: Deutsches Orient Institut (Mitteilungen Band 60/2001).ISBN3-89173-061-6

- Engin, Ismail & Franz, Erhard (2001).Aleviler / Alewiten. Cilt 3 Band: Siyaset ve Örgütler / Politik und Organisationen.Hamburg: Deutsches Orient Institut (Mitteilungen Band 61/2001).ISBN3-89173-062-4

- Kehl-Bodrogi, Krisztina (1992).Die Kizilbas/Aleviten. Untersuchungen über eine esoterische Glaubensgemeinschaft in Anatolien. Die Welt des Islams,(New Series), Vol. 32, No. 1.

- Kitsikis, Dimitri(1999). Multiculturalism in the Ottoman Empire: The Alevi Religious and Cultural Community, in P. Savard & B. Vigezzi eds.Multiculturalism and the History of International RelationsMilano: Edizioni Unicopli.

- Kjeilen, Tore (undated). "AlevismArchived4 June 2012 at theWayback Machine,"in the (online)Encyclopedia of the Orient.

- Shankland, David (2003).The Alevis in Turkey: The Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition.Curzon Press.

- Shindeldecker, John (1996).Turkish Alevis Today.Istanbul: Sahkulu.

- White, Paul J., & Joost Jongerden (eds.) (2003).Turkey’s Alevi Enigma: A Comprehensive Overview.Leiden: Brill.

- Yaman, Ali & Aykan Erdemir (2006).Alevism-Bektashism: A Brief Introduction,London: England Alevi Cultural Centre & Cem Evi.ISBN975-98065-3-3

- Zeidan, David (1999) "The Alevi of Anatolia."Middle East Review of International Affairs 3/4.

- Kurdish Alevis

- Bumke, Peter (1979). "Kizilbaş-Kurden in Dersim (Tunceli, Türkei). Marginalität und Häresie."Anthropos74, 530–548.

- Gezik, Erdal (2000), Etnik Politik Dinsel Sorunlar Baglaminda Alevi Kurtler, Ankara.

- Van Bruinessen, Martin (1997)."Aslını inkar eden haramzadedir! The Debate on the Kurdish Ethnic Identity of the Kurdish Alevis."In K. Kehl-Bodrogi, B. Kellner-Heinkele, & A. Otter-Beaujean (eds),Syncretistic Religious Communities in the Near East(Leiden: Brill).

- Van Bruinessen, Martin (1996).Kurds, Turks, and the Alevi revival in Turkey.Middle East Report,No. 200, pp. 7–10. (NB: The online version is expanded from its original publication.)

- White, Paul J. (2003), "The Debate on the Identity of ‘Alevi Kurds’." In: Paul J. White/Joost Jongerden (eds.)Turkey’s Alevi Enigma: A Comprehensive Overview.Leiden: Brill, pp. 17–32.

- Alevi / Bektashi history

- Birge, John Kingsley (1937).The Bektashi order of dervishes,London and Hartford.

- Brown, John P. (1868),The Dervishes; or, Oriental Spiritualism.

- Küçük, Hülya (2002)The Roles of the Bektashis in Turkey’s National Struggle.Leiden: Brill.

- Mélikoff, Irène (1998).Hadji Bektach: Un mythe et ses avatars. Genèse et évolution du soufisme populaire en Turquie.Leiden: Islamic History and Civilization, Studies and Texts, volume 20,ISBN90-04-10954-4.

- Shankland, David (1994). "Social Change and Culture: Responses to Modernization in an Alevi Village in Anatolia." In C.N. Hann, ed.,When History Accelerates: Essays on Rapid Social Change, Complexity, and Creativity.London: Athlone Press.

- Yaman, Ali (undated). "Kizilbash Alevi Dedes."(Based on his MA thesis forIstanbul University.)

- Ghulat sects in general

- Halm, H. (1982).Die Islamischegnosis:Die extreme Schia und die Alawiten.Zürich.

- Krisztina Kehl-Bodrogi, Krisztina, & Barbara Kellner-Heinkele, Anke Otter-Beaujean, eds. (1997)Syncretistic Religious Communities in the Near East.Leiden: Brill, pp. 11–18.

- Moosa, Matti (1988).Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects,Syracuse University Press.

- Van Bruinessen, Martin (2005). "Religious practices in the Turco-Iranian world: continuity and change."French translation published as:" Les pratiques religieuses dans le monde turco-iranien: changements et continuités ",Cahiers d'Études sur la Méditerranée Orientale et le Monde Turco-Iranien,no. 39–40, 101–121.

- Alevi Identity

- Erdemir, Aykan (2005). "Tradition and Modernity: Alevis' Ambiguous Terms and Turkey's Ambivalent Subjects",Middle Eastern Studies,2005, vol.41, no.6, pp. 937–951.

- Greve, Martin and Ulas Özdemir and Raoul Motika, eds. 2020.Aesthetic and Performative Dimensions of Alevi Cultural Heritage.Ergon Verlag. 215 pages.ISBN978-3956506406

- Koçan, Gürcan/Öncü, Ahmet (2004) "Citizen Alevi in Turkey: Beyond Confirmation and Denial."Journal of Historical Sociology,17/4, pp. 464–489.

- Olsson, Tord & Elizabeth Özdalga/Catharina Raudvere, eds. (1998).Alevi Identity: Cultural, Religious and Social Perspectives.Istanbul: Swedish Research Institute.

- Stokes, Martin (1996). "Ritual, Identity and the State: An Alevi (Shi’a) Cem Ceremony." In Kirsten E. Schulze et al. (eds.),Nationalism, Minorities and Diasporas: Identities and Rights in the Middle East,,pp. 194–196.

- Vorhoff, Karin (1995).Zwischen Glaube, Nation und neuer Gemeinschaft: Alevitische Identität in der Türkei der Gegenwart.Berlin.

- Alevism in Europe

- Geaves, Ron (2003) "Religion and Ethnicity: Community Formation in the British Alevi Community." Koninklijke Brill NV 50, pp. 52– 70.

- Kosnick, Kira (2004) "‘Speaking in One’s Own Voice’: Representational Strategies of Alevi Turkish Migrants on Open-Access Television in Berlin."Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,30/5, pp. 979–994.

- Massicard, Elise (2003) "Alevist Movements at Home and Abroad: Mobilization Spaces and Disjunction."New Perspective on Turkey,28, pp. 163–188.

- Rigoni, Isabelle (2003) "Alevis in Europe: A Narrow Path towards Visibility." In: Paul J. White/Joost Jongerden (eds.) Turkey's Alevi Enigma: A Comprehensive Overview, Leiden: Brill, pp. 159–173.

- Sökefeld, Martin (2002) "Alevi Dedes in the German Diaspora: The Transformation of a Religious Institution."Zeitschrift für Ethnologie,127, pp. 163–189.

- Sökefeld, Martin (2004) "Alevis in Germany and the Question of Integration" paper presented at the Conference on the Integration of Immigrants from Turkey in Austria, Germany and Holland,Boğaziçi University,Istanbul, February 27–28, 2004.

- Sökefeld, Martin & Suzanne Schwalgin (2000). "Institutions and their Agents in Diaspora: A Comparison of Armenians in Athens and Alevis in Germany." Paper presented at the sixth European Association of Social Anthropologist Conference, Krakau.

- Thomä-Venske, Hanns (1990). "The Religious Life of Muslim in Berlin." In: Thomas Gerholm/Yngve Georg Lithman (eds.)The New Islamic Presence in Western Europe,New York: Mansell, pp. 78–87.

- Wilpert, Czarina (1990) "Religion and Ethnicity: Orientations, Perceptions and Strategies among Turkish Alevi and Sunni Migrants in Berlin." In: Thomas Gerholm/Yngve Georg Lithman (eds.)The New Islamic Presence in Western Europe.New York: Mansell, pp. 88–106.

- Zirh, Besim Can (2008) "Euro-Alevis: From Gastarbeiter to Transnational Community." In: Anghel, Gerharz, Rescher and Salzbrunn (eds.) The Making of World Society: Perspectives from Transnational Research. Transcript; 103–130.

- Bibliographies

- Vorhoff, Karin. (1998), "Academic and Journalistic Publications on the Alevi and Bektashi of Turkey." In: Tord Olsson/Elizabeth Özdalga/Catharina Raudvere (eds.) Alevi Identity: Cultural, Religious and Social Perspectives, Istanbul: Swedish Research Institute, pp. 23–50.

- Turkish-language works

- Ata, Kelime. (2007), Alevilerin İlk Siyasal Denemesi: (Türkiye Birlik Partisi) (1966–1980). Ankara: Kelime Yayınevi.

- Aydın, Ayhan. (2008), Abidin Özgünay: Yazar Yayıncı ve Cem Dergisi Kurucusu. İstanbul: Niyaz Yayınları.

- Balkız, Ali. (1999), Sivas’tan Sydney’e Pir Sultan. Ankara: İtalik.

- Balkız, Ali. (2002), Pir Sultan’da Birlik Mücadelesi (Hızır Paşalar’a Yanıt). Ankara: İtalik.

- Bilgöl, Hıdır Ali. (1996), Aleviler ve Canlı Fotoğraflar, Alev Yayınları.

- Coşkun, Zeki (1995) Aleviler, Sünniler ve... Öteki Sivas, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları.

- Dumont, Paul. (1997), "Günümüz Türkiye’sinde Aleviliğin Önemi" içinde Aynayı Yüzüme Ali Göründü Gözüme: Yabancı Araştırmacıların Gözüyle Alevilik, editör: İlhan Cem Erseven. İsntabul: Ant, 141–161.

- Engin, Havva ve Engin, Ismail (2004). Alevilik. Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi.

- Gül, Zeynel. (1995), Yol muyuz Yolcu muyuz? İstanbul: Can Yayınları.

- Gül, Zeynel. (1999), Dernekten Partiye: Avrupa Alevi Örgütlenmesi. Ankara: İtalik.

- Güler, Sabır. (2008), Aleviliğin Siyasal Örgütlenmesi: Modernleşme, Çözülme ve Türkiye Birlik Partisi. Ankara: Dipnot.

- İrat, Ali Murat. (2008), Devletin Bektaşi Hırkası / Devlet, Aleviler ve Ötekiler. İstanbul: Chiviyazıları.

- Kaleli, Lütfü. (2000), "1964–1997 Yılları Arasında Alevi Örgütleri" içinde Aleviler/Alewiten: Kimlik ve Tarih/ Indentität und Geschichte, editörler: İsmail Engin ve Erhard Franz. Hamburg: Deutsches Orient-Institut, 223–241.

- Kaleli, Lütfü. (2000), Alevi Kimliği ve Alevi Örgütlenmeri. İstanbul: Can Yayınları.

- Kaplan, İsmail. (2000), "Avrupa’daki Alevi Örgütlenmesine Bakış" içinde Aleviler/Alewiten: Kimlik ve Tarih/ Indentität und Geschichte, editörler: İsmail Engin ve Erhard Franz. Hamburg: Deutsches Orient-Institut, 241–260.

- Kaplan, İsmail. (2009), Alevice: İnancımız ve Direncimiz. Köln: AABF Yayınları.

- Kocadağ, Burhan. (1996), Alevi Bektaşi Tarihi. İstanbul: Can Yayınları.

- Massicard, Elise. (2007), Alevi Hareketinin Siyasallaşması. İstanbul: İletişim.

- Melikoff, Irene. (1993), Uyur İdik Uyardılar. İstanbul: Cem Yayınevi.

- Okan, Murat. (2004), Türkiye’de Alevilik / Antropolojik Bir Yaklaşım. Ankara: İmge.

- Özerol, Süleyman. (2009), Hasan Nedim Şahhüseyinoğlu. Ankara: Ürün.

- Şahhüseyinoğlu, H. Nedim. (2001), Hızır Paşalar: Bir İhracın Perde Arkası. Ankara: İtalik.

- Şahhüseyinoğlu, Nedim. (1997), Pir Sultan Kültür Derneği’nin Demokrasi Laiklik ve Özgürlük Mücadelesi. Ankara: PSAKD Yayınları.

- Şahhüseyinoğlu, Nedim. (2001), Alevi Örgütlerinin Tarihsel Süreci. Ankara: İtalik.

- Salman, Meral. 2006, Müze Duvarlarına Sığmayan Dergah: Alevi – Bektaşi Kimliğinin Kuruluş Sürecinde Hacı Bektaş Veli Anma Görenleri. Ankara: Kalan.

- Saraç, Necdet. (2010), Alevilerin Siyasal Tarihi. İstanbul: Cem.

- Şener, Cemal ve Miyase İlknur. (1995), Şeriat ve Alevilik: Kırklar Meclisi’nden Günümüze Alevi Örgütlenmesi. İstanbul: Ant.

- Tosun, Halis. (2002), Alevi Kimliğiyle Yaşamak. İstanbul: Can Yayınları.

- Vergin, Nur (2000, [1981]), Din, Toplum ve Siyasal Sistem, İstanbul: Bağlam.

- Yaman, Ali (2000) "Anadolu Aleviliği’nde Ocak Sistemi Ve Dedelik Kurumu."Alevi Bektaşi.

- Zırh, Besim Can. (2005), "Avro-Aleviler: Ziyaretçi İşçilikten Ulus-aşırı Topluluğa" Kırkbudak 2: 31–58.

- Zırh, Besim Can. (2006), "Avrupa Alevi Konfederasyonu Turgut Öker ile Görüşme" Kırkbudak 2: 51–71.

External links

[edit]- Official Alevi-Bektashi Order of Derwishes website(in English)

- A Sufi Metamorphosis: Imam Ali

- History of Sufism / Islamic Mysticism and the importance of Ali

- Alevis(in English)

- Alevi Bektaşi Research Site(in Turkish)

- Semah from a TV show(YouTube)

- Semah – several samples(YouTube)