Almohad doctrine

Almohad doctrine(Arabic:الدَّعوَة المُوَحِّدِيَّة) orAlmohadismwas the ideology underpinning the Almohad movement, founded byIbn Tumart,which created theAlmohad Empireduring the 12th to 13th centuries.[1][2]Fundamental to Almohadism was Ibn Tumart's radical interpretation oftawḥid— "unity" or "oneness" —from which the Almohads get their name:al-muwaḥḥidūn(المُوَحِّدون).[1][3]: 246

The literalist ideology and policies of the Almohads involved a series of attempted radical changes toIslamicreligious and social doctrine under their rule. These policies affected large parts of theMaghreband altered the existing religious climate inal-Andalus(IslamicSpainandPortugal) for many decades.[4][5]They marked a major departure from the social policies and attitudes of earlier Muslim governments in the region, including the precedingAlmoraviddynasty which had followed its own reformist agenda.[1][2]The teachings of Ibn Tumart were compiled in the bookAʿazzu Mā Yuṭlab.[1][6]

On the grounds that Ibn Tumart proclaimed himself to be themehdi,or renewer—not only of Islam, but of "the pure monotheistic message" common to Islam, Christianity, and Judaism—the Almohads rejected the status ofDhimmacompletely.[1]: 171–172 As the Almohad Caliphate expanded,Abd al-Mu'minordered Jews and Christians in conquered territories—as well as theKharijites,Maliki Sunnis,andShi‘isof the Muslim majority—to accept Almohad Islam, depart, or risk death.[1]: 171–172 The Almohad conquest ofal-Andalusled to the emigration of Andalusi Christians from southern Iberia to the Christian north, especially to theTagus valleyandToledo.[1]: 173–174 Andalusi Jews, an urban and visible population, faced intense, often violent Almohad pressure to convert, and many, instead of leaving life as a minority in one place to hazard life as a minority in another, converted at least superficially, though many of these converts continued to face discrimination.[1]: 174–176 After the 13th century collapse of the Almohad Caliphate, an Arabized Jewish population reappeared in the Maghreb, but a Christian one did not.[1]: 176

Origins

[edit]Religious climate before Almohads

[edit]During its golden age,al-Andalus(in present-day Spain and Portugal) was open to a good deal of religious tolerance. For the most part the Almoravids let otherPeople of the Book,or other religions that held the Old Testament as a holy text, practice their religion freely.[7]The Almoravids, were more fundamentalist than previous Muslim rulers of Spain, championing a strict adherence to theMaliki schoolof Islamic law.[8][9]

Thegolden age for Jews in the Iberian Peninsulais considered to be under the relatively tolerant rule of theUmayyad Caliphatein al-Andalus. It was generally a time when Jews were free to conduct business and practice their religion under the limitations ofDhimmistatus.[10]

Rise to power

[edit]

The Almohads were led byIbn Tumart,regarded by historians as a fundamentalist who was convinced that it was his destiny to reform Islam. Ibn Tumart claimed to be themahdi,a title which elevated him to something similar to amessiahor leader of a redemption of righteous Islamic order.[1]He was an intelligent and charismatic man; he claimed to be a direct descendant ofMuhammad.He had studied inAlexandria,Córdoba,Mecca,andBaghdad,[7]and his charismatic preaching earned him a devoted group of followers.

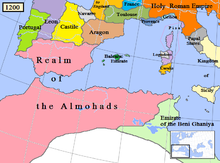

He presented a different religious view that caused outright hostility on theIberian Peninsula[11]after the Almohads crossed theStrait of Gibraltarin 1146.[12]Their rule quickly spread across the Muslim territories of the peninsula (known as Al-Andalus). At their height they were one of the most powerful forces in the westernMediterranean.They were a determined military and economic force, defeating Christian forces primarily composed of Castilians at theBattle of Alarcos.[13]

Ibn Tumart himself died in 1130, well before the Almohads' main military successes, and had no spiritual successor. However, the political leadership of his movement passed on toAbd al-Mu'min,who effectively founded the ruling Almohad dynasty. He and his successors had very different personalities from Ibn Tumart but nonetheless pursued his reforms, culminating in a particularly aggressive push byYa'qub al-Mansur(who arguably ruled at the apogee of Almohad power in the late 12th century).[1]: 255–258

Religious doctrine and ideology

[edit]Tawḥīd

[edit]The Almohad ideology preached by Ibn Tumart is described byAmira Bennisonas a "sophisticated hybrid form of Islam that wove together strands fromHadithscience,ZahiriandShafi'ifiqh,Ghazaliansocial actions (hisba), and spiritual engagement withShi'inotions of theimamandmahdi".[1]: 246 This contrasted with the highly orthodox or traditionalistMalikischool (maddhab) ofSunni Islamwhich predominated in the region up to that point. Central to his philosophy, Ibn Tumart preached a fundamentalist or radical version oftawhid– referring to a strict monotheism or to the "oneness of God". This notion gave the movement its name:al-Muwaḥḥidūn(Arabic:المُوَحِّدون), meaning roughly "those who advocatetawhid",which was adapted to" Almohads "in European writings.[1]: 246 Ibn Tumart saw his movement as a revolutionary reform movement much asearly Islamsaw itself relative to the Christianity and Judaism which preceded it, with himself as itsmahdiand leader.[1]: 246 Whereas the Almoravids before him saw themselves as emirs nominally acknowledging theAbbasidsascaliphs,the Almohads established their own rival caliphate, rejecting Abbasid moral authority as well as the local Maliki establishment.[15][1]

Law

[edit]The Almohad judicial system has been described as looking to the letter of the law rather than the deeper intended purpose of the law.[citation needed]They primarily followed theZahiri schooloffiqhwithinSunni Islam;under the reign ofAbu Yaqub Yusuf,chief judgeIbn Maḍāʾoversaw the banning of any religious material written by non-Zahirites.[16]Abu Yaqub's son Abu Yusuf went even further, actually burning non-Zahirite religious works instead of merely banning them.[17]They trained new judges, who were given schooling in both the religious and military arts.[11]

Theology

[edit]In terms ofIslamic theology,the Almohads wereAsh'arites,their Zahirite-Ash'arism giving rise to a complicated blend of literalist jurisprudence and esoteric dogmatics.[18][19]Some authors occasionally describe Almohads as heavily influenced byMu'tazilism.[20]Scholar Madeline Fletcher argues that while one of Ibn Tumart's original teachings, themurshidas (a collection of sayings memorized by his followers), holds positions on theattributes of Godwhich might be construed as moderately Mu'tazilite (and which were criticized as such byIbn Taimiyya), identifying him with Mu'tazilites would be an exaggeration. She points out that another of his main texts, the'aqida(which was likely edited by others after him), demonstrates a much clearer Ash'arite position on a number of issues.[21]

Nonetheless, the Almohads, particularly from the reign of CaliphAbu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansuronward, embraced the use oflogicalreasoningas a method of validating the more central Almohad concept oftawhid.This effectively provided a religious justification for philosophy and for arationalistintellectualism in Almohad religious thought. Al-Mansur's father,Abu Ya'qub Yusuf,had also shown some favour towards philosophy and kept the philosopherIbn Tufaylas his confidant.[21][22]Ibn Tufayl in turn introducedIbn Rushd(Averroes) to the Almohad court, to whom Al-Mansur gave patronage and protection. Although Ibn Rushd (who was also anIslamic judge) saw rationalism and philosophy as complimentary to religion and revelation, his views failed to convince the traditional Malikiulema,with whom the Almohads were already at odds.[22]: 261 After the decline of Almohadism, Maliki Sunnism ultimately became the dominant official religious doctrine of the region.[23]By contrast, the teachings of Ibn Rushd and other philosophers like him were far more influential for Jewish philosophers – includingMaimonides,his contemporary – and Christian Latin scholars – likeThomas Aquinas– who later promoted his commentaries onAristotle.[22]: 261

Dissemination

[edit]Arabic-Berber bilingualism

[edit]Thekhuṭbas(fromخطبة,the Friday sermon) of the Almohads were essential to the dissemination of Almohad doctrine and ideology.[24]One of the most important Almohad innovations in thekhuṭbawas the imposition ofBerber language—oral-lisān al-gharbī(اللسان الغربي'the western tongue') as the Andalusi historianIbn Ṣāḥib aṣ-Ṣalātdescribed it—as an official liturgical language; bilingualism became a feature of Almohad preaching in both al-Andalus and the Maghreb.[24]Ibn Tumart was described by an anonymous chronicler of the Almohads as "afṣaḥ an-nāss(the most eloquent of the people) in Arabic and Berber. "[24]Under the Almohads, thekhaṭīb,or sermon-giver, ofal-Qarawiyyīn Mosquein Fes, Mahdī b. ‘Īsā, was replaced by Abū l-Ḥasan b. ‘Aṭiyya khaṭīb because the latter was fluent in Berber.[24]

Almohad creed

[edit]It was obligatory in thekhuṭbato repeat the "Almohad creed," with blessings upon the Mahdi Ibn Tumart and affirmation of his claimedhidāyaandprophetic lineage.[24]UnderAbd al-Mu'min,Ibn Tumart's sermon became institutionalized as what contemporary sources calledkhuṭbat al-Muwaḥḥidīn(خطبة الموحدين,'khuṭba of the Almohads') oral-khuṭba l-ma‘lūma(الخطبة المعلومة,'the well-known sermon').[24]Thiskhuṭbawas delivered by every Almohadkhaṭīb,and also on theḥarakasof the sultan and his courts betweenMarrakeshandSeville.[24]

Treatment of non-Muslims

[edit]At their peak in the 1170s, the Almohads had firm control over most of Islamic Spain, and were not threatened by the Christian forces to the north.[13]Once the Almohads took control of southern Spain and Portugal, they introduced a number of very strict religious laws. Even before they took complete control in the 1170s, they had begun removing non Muslims from positions of power.[25]

Jews and Christians were denied freedom of religion, with many sources relating that the Almohads rejected the very concept ofdhimmi(the official protected but subordinate status of Jews and Christians under Islamic rule) and insisted that all people should accept Ibn Tumart asmahdi.[1]: 171 During his siege against theNormansinMahdia,Abd al-Mu'min infamously declared that Christians and Jews must choose betweenconversion or death.[1]: 173 Likewise, the Almohads officially regarded all non-Almohads, including non-Almohad Muslims, as false monotheists and in multiple cases massacred or punished the entire population of a town, both Muslim and non-Muslim, for defying them.[1]Generally, however, the enforcement of this ideological position varied greatly from place to place and appears to have been especially tied to whether or not local communities resisted the Almohad armies as they advanced.[1]However, as the Almohads were on a self-declaredjihad,they were willing to use brutal techniques to back up their holy war.[26]In some cases the threats of violence were carried out locally as a warning to others even if the authorities did not have the ability to actually follow through on a larger scale.[1]NativeChristians in al-Andaluswho were living under Muslim rule up until this point had the option to escape to Christian-controlled lands to the north, and many did so.Alfonso VIIofLeonandCastilealso encouraged them to flee by offering them lands if they migrated to his territory.[1]: 173–174 Jews, however, were particularly vulnerable as they faced an uncertain minority status in both Christian or Muslim territory, as well as because they lived mainly in urban areas where they were especially visible to authorities.[1]Many were killed in the course of Almohad invasions or repressions.[25]

This pressure to convert resulted in many conversions under duress which were insincere, with many Christians and Jews officially converting in order to escape violence while preserving their livelihoods. Even the famous Jewish philosopherMaimonideswas reported to have officially converted to Islam under Almohad rule when he moved fromCordobatoFes,before finally leaving for Egypt where he was able to live openly as a Jew again.[1]: 174 Half-hearted oaths were certainly not looked to as ideal and brought a lot of problems for the population of al-Andalus, much as it did during theforced conversion of Muslimsand Jewsin Spainand Portugala few centuries later.[1]The Almohads recognized that many of the conversions by Jews were not particularly sincere, which certainly did not help to promote social and religious unity.[25]They responded to this by imposing severe regulations on the business of former Jews.Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansurset up a strict dress code for Jews living within Almohad territory: Jews had to wear dark blue or black, the traditional colors of mourning in Islam, which further entrenched discrimination.[27]

Decline

[edit]

In al-Andalus the Almohad caliphate was decisively defeated by the combined Christian forces ofPortugal,Castile,andAragonat theBattle of Las Navas de Tolosa,in 1212.[28]The battle is recognized as one of the most important events in thereconquistamovement in Spain. Not only was it a decisive defeat of the Muslim forces, it was also one of the first times the fractured Christian kingdoms of the north came together for the common goal of reclaiming the peninsula.[citation needed]

Following 1212 the Almohad Caliphate's power declined and the revolutionary religious dogmatism of Ibn Tumart began to fade as later Almohad dynastic rulers were more preoccupied with the practicalities of maintaining the empire over a wide region whose population largely did not subscribe to Almohadism. This culminated in 1229 when Caliph al-Ma'mun publicly repudiated Ibn Tumart's status asmahdi.[1]: 116 This declaration may have been an attempt to appease the Muslim population of al-Andalus, but it also allowed for one Almohad faction, theHafsids,to disavow his leadership and declare the eastern part of the empire inIfriqiya(Tunisia) to be independent, thus founding the Hafsid state.[1][2]

By 1270, the Almohads were no longer a force of any significance on the Iberian Peninsula or Morocco. After their fall, the fundamentalist religious doctrine that they supported was relaxed once again. Some scholars consider that Ibn Tumart's overall ideological mission ultimately failed, but that, like the Almoravids, his movement nonetheless played a role in the history ofIslamizationin the region.[1]: 246 One holdover for Jews was a law that stated that people who converted to Islam would be put to death if they reconverted.[29]

The Hafsids of Tunisia, in turn, officially declared themselves the true "Almohads" after their independence from Marrakesh but this identity and ideology lessened in importance over time. The early Hafsid leadership mainly attempted to keep the Almohads as a political elite more than a religious elite in a region that was otherwise predominantlyMalikiSunni in orientation. Eventually, the Almohads were merely one among multiple factions competing for power in their state.[2]After 1311, when Sultan al-Lihyani took power withAragonesehelp, Ibn Tumart's name was dropped from thekhutba(the main community sermon on Fridays), effectively signaling the end of public support for Almohad doctrine.[2]: 127 Over the 14th century the Malikiulama(scholars) increasingly occupied positions in the state and were thede factoreligious authorities.[2]: 132–133

References

[edit]- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabBennison, Amira K.(2016).The Almoravid and Almohad Empires.Edinburgh University Press.ISBN9780748646821.

- ^abcdefAbun-Nasr, Jamil (1987).A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0521337674.

- ^"7. Fiqh".Brockelmann in English: The History of the Arabic Written Tradition Online.doi:10.1163/97890043200862542-8098_breo_com_122070.Retrieved2022-10-20.

- ^Pascal Buresi and Hicham El Aallaoui,Governing the Empire: Provincial Administration in the Almohad Caliphate 1224-1269,pg. 170. Volume 3 of Studies in the History and Society of the Maghrib. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2012.ISBN9789004233331

- ^Dominique Urvoy,The Ulama of al-Andalus,pg. 868. Taken fromThe Legacy of Muslim Spain,Volume 12 of Handbook of Oriental Studies: The Near and Middle East. Eds.Salma Khadra Jayyusiand Manuela Marín. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1992.ISBN9789004095991

- ^abIbn Tūmart, Muḥammad (1997) [originally recorded approximately 1130]. Abū al-ʻAzm, ʻAbd al-Ghanī (ed.).Aʻazz mā yuṭlab.Rabat: Muʼassasat al-Ghanī lil-Nashr.ISBN9981-891-11-8.OCLC40101950.

- ^abAllen Fromherz,"North Africa and the Twelfth-century Renaissance: Christian Europe and the Almohad Islamic Empire",Islam & Christian-Muslim Relations20, no. 1 (January 2009): 43-59.

- ^Lay, Stephen (2008).The Reconquest Kings of Portugal: Political and Cultural Reorientation on the Medieval Frontier.Springer. p. 31.ISBN978-0-230-58313-9.

- ^Messier, Ronald A. (2010).The Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad.Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. xiv, 206 (and elsewhere).ISBN978-0-313-38590-2.

- ^Fernandez-Morera, Dario (April 1, 2013)."Some Overlooked Realities of Jewish Life under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain".Comparative Civilizations Review.68(68): 16 – via BYU Scholars Archive.

- ^abMadeleine Fletcher, "The Almohad Tawhīd: Theology Which Relies on Logic",Numen,v. 38, no. 1 (June 1, 1991): 110-127

- ^Amira Bennison,"The Almohads and the Qur'ān of Uthm ān: The Legacy of the Umayyads of Cordoba in the Twelfth Century Maghrib",Al-Masaq: Islam & the Medieval Mediterranean19, no. 2 (2007): 131-154.

- ^abJ. F. Powers,"The Early Reconquest Episcopate at Cuenca, 1177–1284",The Catholic Historical Review,v. 87, no. 1 (2001): 1-16.

- ^Bennison, Amira (2016).Almoravid and Almohad Empires.Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 99.ISBN9780748646821.Retrieved19 October2022.

- ^Maribel Fierro, "Alfonso X 'The Wise': The Last Almohad Caliph?",Medieval Encounters15, no. 2-4 (December 2009): 175-198.

- ^Kees Versteegh,The Arabic Linguistic Tradition,pg. 142. Part of Landmarks in Linguistic Thought series, vol. 3.New York:Routledge,1997.ISBN9780415157575

- ^Shawqi Daif,Introduction to Ibn Mada'sRefutation of the Grammarians,pg. 6. Cairo, 1947.

- ^Kojiro Nakamura,"Ibn Mada's Criticism of Arab Grammarians."Orient,v. 10, pp. 89–113. 1974

- ^Pascal Buresi and Hicham El Aallaoui,Governing the Empire: Provincial Administration in the Almohad Caliphate 1224–1269,p. 170. Volume 3 of Studies in the History and Society of the Maghrib. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2012.ISBN9789004233331

- ^Nazeer Ahmed, Dr (10 July 2001).Islam in Global History: Volume One: From the Death of Prophet Muhammed to the First World War.ISBN9781462831302.

- ^abFletcher, Madeleine (1991). "The Almohad Tawhīd: Theology Which Relies on Logic".Numen.38:110–127.doi:10.1163/156852791X00060.

- ^abcBennison, Amira K. (2016).The Almoravid and Almohad Empires.Edinburgh University Press.ISBN9780748646821.

- ^Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987).A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0521337674.

- ^abcdefg"The Preaching of the Almohads: Loyalty and Resistance across the Strait of Gibraltar",Spanning the Strait,BRILL, pp. 71–101, 2013-01-01,doi:10.1163/9789004256644_004,ISBN9789004256644,retrieved2023-02-13

- ^abcNorman Roth, "The Jews and the Muslim Conquest of Spain",Jewish Social Studies38, no. 2 (Spring 1976): 145-158.

- ^Maribel Fierro,"Decapitation of Christians and Muslims in the Medieval Iberian Peninsula: Narratives, Images, Contemporary Perceptions",Comparative Literature Studies,v. 45, no. 2 (2008): 137-164.

- ^Comparative Literature Studies,"The Decline of the Almohads: Reflections on the Viability of Religious Movements",History of Religions,v. 4, no. 1 (July 1, 1964): 23-29.

- ^Isabel O’Connor, "The Fall of the Almohad Empire in the Eyes of Modern Spanish Historians",Islam & Christian-Muslim Relations14, no. 2 (April 2003): 145

- ^Amira Bennison, "The Almohads and the Qur’ān of Uthm ān: The Legacy of the Umayyads of Cordoba in the Twelfth Century Maghrib",Al-Masaq: Islam & the Medieval Mediterranean19, no. 2 (2007): 131-154.