Ambush predator

Ambush predatorsorsit-and-wait predatorsarecarnivorous animalsthatcapturetheirpreyviastealth,luringor by (typicallyinstinctive)strategiesutilizing an element of surprise. Unlikepursuit predators,who chase to capture prey using sheerspeedorendurance,ambush predators avoidfatigueby staying in concealment, waiting patiently for the prey to get near, before launching a sudden overwhelming attack that quickly incapacitates and captures the prey.

The ambush is often opportunistic, and may be set by hiding in aburrow,bycamouflage,byaggressive mimicry,or by the use of a trap (e.g. aweb). The predator then uses a combination ofsensestodetectand assess the prey, and to time the strike. Nocturnal ambush predators such ascatsandsnakeshave vertical slitpupilshelping them to judge the distance to prey in dim light. Different ambush predators use a variety of means to capture their prey, from the long sticky tongues ofchameleonsto the expanding mouths offrogfishes.

Ambush predation is widely distributed in theanimalkingdom, spanning some members of numerous groups such as thestarfish,cephalopods,crustaceans,spiders,insectssuch asmantises,andvertebratessuch as manysnakesandfishes.

Strategy[edit]

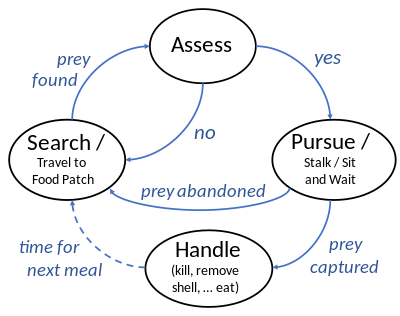

Ambush predators usually remain motionless (sometimes hidden) and wait for prey to come within ambush distance before pouncing. Ambush predators are oftencamouflaged,and may be solitary.Pursuit predationbecomes a better strategy than ambush predation when the predator is faster than the prey.[2]Ambush predators use many intermediate strategies. For example, when a pursuit predator is faster than its prey over a short distance, but not in a long chase, then either stalking or ambush becomes necessary as part of the strategy.[2]

Bringing the prey within range[edit]

Concealment[edit]

Ambush often relies on concealment, whether by staying out of sight or by means of camouflage.

Burrows[edit]

Ambush predators such astrapdoor spidersandAustralian crab spiderson land andmantis shrimpsin the sea rely on concealment, constructing and hiding in burrows. These provide effective concealment at the price of a restricted field of vision.[3][4][5][6]

Trapdoor spiders excavate a burrow and seal the entrance with a web trapdoor hinged on one side with silk. The best-known is the thick, bevelled "cork" type, which neatly fits the burrow's opening. The other is the "wafer" type; it is a basic sheet of silk and earth. The door's upper side is often effectively camouflaged with local materials such as pebbles and sticks. The spider spins silk fishing lines, or trip wires, that radiate out of the burrow entrance. When the spider is using the trap to capture prey, itschelicerae(protruding mouthparts) hold the door shut on the end furthest from the hinge. Prey make the silk vibrate, and alert the spider to open the door and ambush the prey.[7][8]

Camouflage[edit]

Many ambush predators make use ofcamouflageso that their prey can come within striking range without detecting their presence. Among insects, coloration inambush bugsclosely matches the flower heads where they wait for prey.[9]Among fishes, thewarteye stargazerburies itself nearly completely in the sand and waits for prey.[10]Thedevil scorpionfishtypically lies partially buried on the sea floor or on a coral head during the day, covering itself with sand and other debris to further camouflage itself.[11][12][13][14]Thetasselled wobbegongis a shark whose adaptations as an ambush predator include a strongly flattened and camouflaged body with afringethat breaks up its outline.[15]Among amphibians, thePipa pipa's brown coloration blends in with the murky waters of the Amazon Rainforest which allows for this species to lie in wait and ambush its prey.[16]

Aggressive mimicry[edit]

Many ambush predators actively attract their prey towards them before ambushing them. This strategy is calledaggressive mimicry,using the false promise of nourishment to lure prey. Thealligator snapping turtleis a well-camouflaged ambush predator. Its tongue bears a conspicuous pink extension that resembles awormand can be wriggled around;[17]fish that try to eat the "worm" are themselves eaten by the turtle. Similarly, some reptiles such asElapherat snakes employcaudal luring(tail luring) to entice small vertebrates into striking range.[18]

Thezone-tailed hawk,which resembles theturkey vulture,flies among flocks of turkey vultures, then suddenly breaks from the formation and ambushes one of them as its prey.[19][20]There is however some controversy about whether this is a true case ofwolf in sheep's clothingmimicry.[21]

Flower mantisesare aggressive mimics, resemblingflowersconvincingly enough to attract prey that come to collect pollen and nectar. Theorchid mantisactually attracts its prey,pollinatorinsects, more effectively than flowers do.[22][23][24][25]Crab spiders,similarly, are coloured like the flowers they habitually rest on, but again, they can lure their prey even away from flowers.[26]

Traps[edit]

Some ambush predators build traps to help capture their prey. Lacewings are a flying insect in the orderNeuroptera.In some species, their larval form, known as theantlion,is an ambush predator. Eggs are laid in the earth, often in caves or under a rocky ledge. The juvenile creates a small, crater shaped trap. The antlion hides under a light cover of sand or earth. When an ant, beetle or other prey slides into the trap, the antlion grabs the prey with its powerful jaws.[27][28]

Some but not allweb-spinningspidersare sit-and-wait ambush predators. The sheetweb spiders (Linyphiidae) tend to stay with their webs for long periods and so resemble sit-and-wait predators, whereas the orb-weaving spiders (such as theAraneidae) tend to move frequently from one patch to another (and thus resemble active foragers).[29]

Detection and assessment[edit]

Ambush predators must time their strike carefully. They need to detect the prey, assess it as worth attacking, and strike when it is in exactly the right place. They have evolved a variety of adaptations that facilitate this assessment. For example,pit vipersprey on small birds, choosing targets of the right size for their mouth gape: larger snakes choose larger prey. They prefer to strike prey that is both warm and moving;[31]their pit organs between the eye and the nostril containinfrared(heat) receptors, enabling them to find and perhaps judge the size of their small, warm-blooded prey.[32]

The deep-sea tripodfishBathypterois grallatoruses tactile and mechanosensory cues to identify food in its low-light environment.[33]The fish faces into the current, waiting for prey to drift by.[34][35][36]

Several species ofFelidae (cats)and snakes have vertically elongated (slit) pupils, advantageous fornocturnalambush predators as it helps them to estimate the distance to prey in dim light; diurnal and pursuit predators in contrast have round pupils.[30]

Capturing the prey[edit]

Ambush predators often have adaptations for seizing their prey rapidly and securely. The capturing movement has to be rapid to trap the prey, given that the attack is not modifiable once launched.[6][37]Zebra mantis shrimpcapture agile prey such as fish primarily at night while hidden in burrows, striking very hard and fast, with a mean peak speed 2.30 m/s (5.1 mph) and mean duration of 24.98 ms.[37]

Chameleons(family Chamaeleonidae) are highly adapted as ambush predators.[38]They can change colour to match their surroundings and often climb through trees with a swaying motion, probably to mimic the movement of the leaves and branches they are surrounded by.[38]All chameleons are primarilyinsectivoresand feed byballistically projectingtheirtongues,often twice the length of their bodies, to capture prey.[39][40]The tongue is projected in as little as 0.07 seconds,[41][42]and is launched at an acceleration of over 41g.[42]Thepowerwith which the tongue is launched, over 3000 W·kg−1,is more than muscle can produce, indicating that energy is stored in an elastic tissue for sudden release.[41]

All fishes face a basic problem when trying to swallow prey: opening their mouth may pull food in, but closing it will push the food out again.Frogfishescapture their prey by suddenly opening their jaws, with a mechanism which enlarges the volume of the mouth cavity up to 12-fold and pulls the prey (crustaceans,molluscsand other whole fishes) into the mouth along with water; the jaws close without reducing the volume of the mouth cavity. The attack can be as fast as 6 milliseconds.[43]

Taxonomic range[edit]

Ambush predation is widely distributed across theanimal kingdom.It is found in many vertebrates including fishes such as the frogfishes (anglerfishes) of the sea bottom, and thepikesof freshwater; reptiles including crocodiles,[44]snapping turtles,[45]themulga dragon,[46]and many snakes such as theblack mamba;[47]mammals such as the cats;[48]and birds such as theanhinga(darter).[49]The strategy is found in several invertebrate phyla including arthropods such asmantises,[50][51][52]purseweb spiders,[53]and somecrustaceans;[3]cephalopodmolluscs such as thecolossal squid;[54]andstarfishsuch asLeptasterias tenera.[55]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Kramer, Donald L. (2001)."Foraging behavior"(PDF).In Fox, C. W.; Roff, D. A.; Fairbairn, D. J. (eds.).Evolutionary Ecology: Concepts and Case Studies.Oxford University Press. pp. 232–238.ISBN9780198030133.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 12 July 2018.Retrieved20 September2018.

- ^abScharf, I.; Nulman, E.; Ovadia, O.; Bouskila, A. (2006)."Efficiency evaluation of two competing foraging modes under different conditions"(PDF).The American Naturalist.168(3): 350–357.doi:10.1086/506921.PMID16947110.S2CID13809116.

- ^abdeVries, M. S.; Murphy, E. A. K.; Patek S. N. (2012)."Strike mechanics of an ambush predator: the spearing mantis shrimp".Journal of Experimental Biology.215(Pt 24): 4374–4384.doi:10.1242/jeb.075317.PMID23175528.

- ^"Trapdoor spiders".BBC.Retrieved12 December2014.

- ^"Trapdoor spider".Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. 2014.Retrieved12 December2014.

- ^abMoore, Talia Y.; Biewener, Andrew A. (2015)."Outrun or Outmaneuver: Predator–Prey Interactions as a Model System for Integrating Biomechanical Studies in a Broader Ecological and Evolutionary Context"(PDF).Integrative and Comparative Biology.55(6): 1188–97.doi:10.1093/icb/icv074.PMID26117833.

- ^"Trapdoor spiders".BBC.RetrievedDecember 12,2014.

- ^"Trapdoor spider".Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. 2014.RetrievedDecember 12,2014.

- ^Boyle, Julia; Start, Denon (2020). Galván, Ismael (ed.)."Plasticity and habitat choice match colour to function in an ambush bug".Functional Ecology.34(4): 822–829.Bibcode:2020FuEco..34..822B.doi:10.1111/1365-2435.13528.ISSN0269-8463.S2CID214302722.

- ^Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2013)."Gillellus uranidea"inFishBase.April 2013 version.

- ^Gosline, William A. (July 1994). "Function and structure in the paired fins of scorpaeniform fishes".Environmental Biology of Fishes.40(3): 219–226.Bibcode:1994EnvBF..40..219G.doi:10.1007/BF00002508.hdl:2027.42/42637.S2CID30229791.

- ^World Database of Marine Species:Spiny devil fishArchived2012-03-04 at theWayback Machine.Accessed 03-22-2010.

- ^Michael, Scott (Winter 2001)."Speak of the devil: fish in the genusInimicus"(PDF).SeaScope.18.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-13.Retrieved2010-03-27.

- ^WetWebMedia:The Ghoulfish/Scorpion/Stonefishes of the Subfamily Choridactylinae (Inimicinae),by Bob Fenner. Accessed 03-27-2010.

- ^Ceccarelli, D. M.; Williamson, D. H. (2012-02-04)."Sharks that eat sharks: opportunistic predation by wobbegongs".Coral Reefs.31(2): 471.Bibcode:2012CorRe..31..471C.doi:10.1007/s00338-012-0878-z.

- ^Buchacher, Christian O. (1993-01-01)."Field studies on the small Surinam toad, Pipa arrabali, near Manaus, Brazil".Amphibia-Reptilia.14(1): 59–69.doi:10.1163/156853893X00192.ISSN1568-5381.

- ^Spindel, E. L.; Dobie, J. L.; Buxton, D. F. (2005). "Functional mechanisms and histologic composition of the lingual appendage in the alligator snapping turtle, Macroclemys temmincki (Troost) (Testudines: Chelydridae)".Journal of Morphology.194(3): 287–301.doi:10.1002/jmor.1051940308.PMID29914228.S2CID49305881.

- ^Mullin, S.J. (1999). "Caudal distraction by rat snakes (Colubridae, Elaphe): A novel behaviour used when capturing mammalian prey".Great Basin Naturalist.59:361–367.

- ^Smith, William John (2009).The Behavior of Communicating: an ethological approach.Harvard University Press. p. 381.ISBN978-0-674-04379-4.

Others rely on the technique adopted by a wolf in sheep's clothing—they mimic a harmless species.... Other predators even mimic their prey's prey: angler fish (Lophiiformes) and alligator snapping turtlesMacroclemys temminckican wriggle fleshy outgrowths of their fins or tongues and attract small predatory fish close to their mouths.

- ^Willis, E. O. (1963). "Is the Zone-Tailed Hawk a Mimic of the Turkey Vulture?".The Condor.65(4): 313–317.doi:10.2307/1365357.JSTOR1365357.

- ^Clark, William S. (2004). "Is the zone-tailed hawk a mimic?".Birding.36(5): 495–498.

- ^Cott, Hugh(1940).Adaptive Coloration in Animals.Methuen.pp.392–393.

- ^Annandale, Nelson (1900). "Observations on the habits and natural surroundings of insects made during the 'Skeat Expedition' to the Malay Peninsula, 1899–1900".Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London.69:862–865.

- ^O'Hanlon, James C.; Holwell, Gregory I.; Herberstein, Marie E. (2014)."Pollinator deception in the orchid mantis".The American Naturalist.183(1): 126–132.doi:10.1086/673858.PMID24334741.S2CID2228423.

- ^Levine, Timothy R. (2014).Encyclopedia of Deception.Sage Publications. p. 675.ISBN978-1-4833-8898-4.

In aggressive mimicry, the predator is 'a wolf in sheep's clothing'. Mimicry is used to appear harmless or even attractive to lure its prey.

- ^Vieira, Camila; Ramires, Eduardo N.; Vasconcellos-Neto, João; Poppi, Ronei J.; Romero, Gustavo Q. (2017)."Crab Spider Lures Prey In Flowerless Neighborhoods".Scientific Reports.7(1): 9188.Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.9188V.doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09456-y.PMC5569008.PMID28835630.

- ^"Video of antlion larva ambushing an ant".National Geographic. Archived fromthe originalon June 17, 2014.RetrievedNovember 30,2014.

- ^"Antlion ambush".BBC.26 January 2012.RetrievedNovember 30,2014.

- ^Janetos, Anthony C. (1982). "Foraging tactics of two guilds of web-spinning spiders".Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology.10(1): 19–27.doi:10.1007/bf00296392.S2CID19631772.

- ^abBanks, M. S.; Sprague, W. W.; Schmoll, J.; Parnell, J. A. Q.; Love, G. D. (2015-08-07)."Why do animal eyes have pupils of different shapes?".Science Advances.1(7): e1500391.Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0391B.doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500391.PMC4643806.PMID26601232.Supplement:List of species by pupil shape.

- ^Shine, R.; Sun, L.-X. (2003)."Attack strategy of an ambush predator: which attributes of the prey trigger a pit-viper's strike?".Functional Ecology.17(3): 340–348.Bibcode:2003FuEco..17..340S.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00738.x.

- ^Fang, Janet (2010-03-14). "Snake infrared detection unravelled".Nature.doi:10.1038/news.2010.122.

- ^Hoar, W. S.; Randall, D. J.; Conte, F. P. (1997).Deep-Sea Fishes.Fish Physiology. Vol. 16. Academic Press. p. 344.ISBN0-12-350440-6.

- ^Hyde, N. (2009).Deep Sea Extremes.Crabtree Publishing Company. p.16.ISBN978-0-7787-4501-3.

- ^Winner, C. (2006).Life on the Edge.Lerner Publications. pp.18.ISBN0-8225-2499-6.

- ^Gage, J. D.; Tyler, P.A. (1992).Deep-sea biology: a natural history of organisms at the deep-sea floor.Cambridge University Press.p. 86.ISBN0-521-33665-1.

- ^abdeVries, M. S.; Murphy, E. A. K.; Patek, S. N. (2012)."Strike mechanics of an ambush predator: the spearing mantis shrimp".Journal of Experimental Biology.215(24): 4374–4384.doi:10.1242/jeb.075317.PMID23175528.

- ^abTolley, Krystal A.; Herrel, Anthony (2013).The Biology of Chameleons.University of California Press.p. 128.ISBN978-0-520-95738-1.

Chameleons may also employ a form of movement-based camouflage,... [they] often rhythmically rock backward and forward as they walk... [perhaps] imitating a swaying leaf... moving in the breeze... The behavior is widespread in highly cryptic, generally slow-moving, ambush predators, notably chameleons and some snakes and mantids

- ^Anderson, C. V.; Sheridan, T.; Deban, S. M. (2012). "Scaling of the ballistic tongue apparatus in chameleons".Journal of Morphology.273(11): 1214–1226.doi:10.1002/jmor.20053.PMID22730103.S2CID21033176.

- ^Anderson, Christopher V. (2009)Rhampholeon spinosusfeeding video.chamaeleonidae

- ^abde Groot, J. H.; van Leeuwen, J. L. (2004)."Evidence for an elastic projection mechanism in the chameleon tongue".Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B.271(1540): 761–770.doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2637.PMC1691657.PMID15209111.

- ^abAnderson, C.V.; Deban, S. M. (2010)."Ballistic tongue projection in chameleons maintains high performance at low temperature".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.107(12): 5495–5499.Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5495A.doi:10.1073/pnas.0910778107.PMC2851764.PMID20212130.

- ^Bray, Dianne."Eastern Frogfish, Batrachomoeus dubius".Fishes of Australia.Archived fromthe originalon 14 September 2014.Retrieved14 September2014.

- ^"Nile Crocodile: Photos, Video, E-card, Map – National Geographic Kids".Kids.nationalgeographic. 2002. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-01-16.Retrieved2010-03-16.

- ^"Common Snapping Turtle".Canadian Museum of Nature. 2013.RetrievedDecember 2,2014.

- ^Browne-Cooper, Robert; Brian Bush; Brad Maryan; David Robinson (2007).Reptiles and Frogs in the Bush: Southwestern Australia.University of Western Australia Press. pp. 145, 146.ISBN9781920694746.

- ^Richardson, Adele (2004).Mambas.Mankato, Minnesota: Capstone Press. p. 25.ISBN9780736821377.Retrieved2010-05-19.

- ^Etnyre, Erica; Lande, Jenna; Mckenna, Alison."Felidae | Cats".Animal Diversity Web.Retrieved28 September2018.

- ^Ryan, P. G. (2007). "Diving in shallow water: the foraging ecology of darters (Aves: Anhingidae)".Journal of Avian Biology.38(4): 507–514.doi:10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.04070.x(inactive 2024-04-29).

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - ^"Praying mantis ambushes a grasshopper".National Geographic. Archived fromthe originalon April 14, 2014.RetrievedNovember 30,2014.

- ^"Nature wildlife: Praying mantis".BBC.RetrievedNovember 30,2014.

- ^"How the praying mantis hides".Pawnation.RetrievedNovember 30,2014.

- ^Piper, R.(2007).Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals.Greenwood Press.ISBN9780313339226.

- ^Bourton, J. (2010)."Monster colossal squid is slow not fearsome predator".BBC.RetrievedDecember 1,2014.

- ^Hendler, G.; Franz, D. R. (1982)."The biology of a brooding seastar,Leptasterias tenera,in Block Island Sound ".Biological Bulletin.162(1): 273–289.doi:10.2307/1540983.JSTOR1540983.Archived fromthe originalon 2015-09-23.Retrieved2014-12-01.

External links[edit]

- Predation lectureUniversity of Washington