Ancient Greece

| History ofGreece |

|---|

|

|

|

| Ancient history |

|---|

| Preceded byprehistory |

|

Ancient Greece(Greek:Ἑλλάς,romanized:Hellás) was a northeasternMediterraneancivilization,existing from theGreek Dark Agesof the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end ofclassical antiquity(c. 600 AD), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically relatedcity-statesand other territories. Most of these regions were officially unified only once, for 13 years, underAlexander the Great'sempirefrom 336 to 323 BC.[a]InWestern history,the era of classical antiquity was immediately followed by theEarly Middle Agesand theByzantineperiod.[1]

Three centuries after theLate Bronze Age collapseofMycenaean Greece,Greek urbanpoleisbegan to form in the 8th century BC, ushering in theArchaic periodandthe colonizationofthe Mediterranean Basin.This was followed by the age ofClassical Greece,from theGreco-Persian Warsto the 5th to 4th centuries BC, and which included theGolden Age of Athens.The conquests of Alexander the Great spread Hellenistic civilization from the western Mediterranean toCentral Asia.TheHellenistic periodended with theconquestof theeastern Mediterraneanworld by theRoman Republic,and the annexation of theRoman provinceofMacedoniainRoman Greece,and later the province ofAchaeaduring theRoman Empire.

ClassicalGreek culture,especially philosophy, had a powerful influence onancient Rome,which carried a version of it throughout theMediterraneanand much of Europe. For this reason, Classical Greece is generally considered the cradle ofWestern civilization,theseminalculture from which the modern West derives many of its founding archetypes and ideas in politics, philosophy, science, and art.[2][3][4]

Chronology

Classical antiquityin the Mediterranean region is commonly considered to have begun in the 8th century BC[5](around the time of the earliest recorded poetry of Homer) and ended in the 6th century AD.

Classical antiquity in Greece was preceded by theGreek Dark Ages(c. 1200–c. 800 BC),archaeologicallycharacterised by theprotogeometricandgeometric stylesof designs on pottery. Following the Dark Ages was theArchaic Period,beginning around the 8th century BC, which saw early developments in Greek culture and society leading to theClassical Period[6]from the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC until the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC.[7]The Classical Period is characterized by a "classical" style, i.e. one which was considered exemplary by later observers, most famously in theParthenonof Athens. Politically, the Classical Period was dominated byAthensand theDelian Leagueduring the 5th century, but displaced bySpartan hegemonyduring the early 4th century BC, before power shifted toThebesand theBoeotian Leagueand finally to theLeague of Corinthled byMacedon.This period was shaped by theGreco-Persian Wars,thePeloponnesian War,and theRise of Macedon.

Following the Classical period was the Hellenistic period (323–146 BC), during which Greek culture and power expanded into theNearandMiddle Eastfrom the death of Alexander until the Roman conquest.Roman Greeceis usually counted from the Roman victory over theCorinthiansat theBattle of Corinthin 146 BC to the establishment ofByzantiumbyConstantineas the capital of theRoman Empirein 330 AD. Finally,Late Antiquityrefers to the period ofChristianizationduring the later 4th to early 6th centuries AD, consummated by the closure of theAcademy of AthensbyJustinian Iin 529.[8]

Historiography

The historical period of ancient Greece is unique in world history as the first period attested directly in comprehensive, narrativehistoriography,while earlier ancient history orprotohistoryis known from much more fragmentary documents such as annals, king lists, and pragmaticepigraphy.

Herodotusis widely known as the "father of history": hisHistoriesare eponymous of the entirefield.Written between the 450s and 420s BC, Herodotus' work reaches about a century into the past, discussing 6th century BC historical figures such asDarius I of Persia,Cambyses IIandPsamtik III,and alluding to some 8th century BC persons such asCandaules.The accuracy of Herodotus' works is debated.[9][10][11][12][13]

Herodotus was succeeded by authors such asThucydides,Xenophon,Demosthenes,PlatoandAristotle.Most were either Athenian or pro-Athenian, which is why far more is known about the history and politics of Athens than of many other cities. Their scope is further limited by a focus on political, military and diplomatic history, ignoring economic and social history.[14]

History

Archaic period

The archaic period, lasting from approximately 800 to 500 BC, saw the culmination of political and social developments which had begun in the Greek dark age, with thepolis(city-state) becoming the most important unit of political organisation in Greece.[15]The absence of powerful states in Greece after the collapse of Mycenaean power, and the geography of Greece, where many settlements were separated from their neighbours by mountainous terrain, encouraged the development of small independent city-states.[16]Several Greek states saw tyrants rise to power in this period, most famously atCorinthfrom 657 BC.[17]The period also saw the founding of Greek colonies around the Mediterranean, withEuboeansettlements atAl-Minain the east as early as 800 BC, andIschiain the west by 775.[18]Increasing contact with non-Greek peoples in this period, especially in the Near East, inspired developments in art and architecture, the adoption of coinage, and the development of the Greek Alpha bet.[19]

Athens developed its democratic system over the course of the archaic period. Already in the seventh century, the right of all citizen men to attend theassemblyappears to have been established.[20]After a failed coup led byCylon of Athensaround 636 BC,Dracowas appointed to establish a code of laws in 621. This failed to reduce the political tension between the poor and the elites, and in 594Solonwas given the authority to enact another set of reforms, which attempted to balance the power of the rich and the poor.[21]In the middle of the sixth century,Pisistratusestablished himself as a tyrant, and after his death in 527 his sonHippiasinherited his position; by the end of the sixth century he had been overthrown andCleisthenescarried out further democratising reforms.[22]

In Sparta, a political system with two kings, acouncil of elders,and fiveephorsdeveloped over the course of the eighth and seventh century. According to Spartan tradition, this constitution was established by the legendary lawgiverLycurgus.[23]Over the course of thefirstandsecond Messenian wars,Sparta subjugated the neighbouring region ofMessenia,enserfing the population.[24]

In the sixth century, Greek city-states began to develop formal relationships with one another, where previously individual rulers had relied on personal relationships with the elites of other cities.[25]Towards the end of the archaic period, Sparta began to build a series of alliances, thePeloponnesian League,with cities includingCorinth,Elis,andMegara,[26]isolating Messenia and reinforcing Sparta's position againstArgos,the other major power in the Peloponnese.[27]Other alliances in the sixth century included those between Elis andHeraeain the Peloponnese; and between the Greek colonySybarisin southern Italy, its allies, and the Serdaioi.[28]

Classical Greece

In 499 BC, theIoniancity states under Persian rule rebelled against their Persian-supported tyrant rulers.[29]Supported by troops sent from Athens andEretria,they advanced as far asSardisand burnt the city before being driven back by a Persian counterattack.[30]The revolt continued until 494, when the rebelling Ionians were defeated.[30]Darius did not forget that Athens had assisted the Ionian revolt, and in 490 he assembled an armada to retaliate.[31]Though heavily outnumbered, the Athenians—supported by theirPlataeanallies—defeated the Persian hordes at theBattle of Marathon,and the Persian fleet turned tail.[32]

Ten years later, asecond invasionwas launched by Darius' sonXerxes.[33]The city-states of northern and central Greece submitted to the Persian forces without resistance, but a coalition of 31 Greek city states, including Athens and Sparta, determined to resist the Persian invaders.[33]At the same time, Greek Sicily was invaded by a Carthaginian force.[33]In 480 BC, the first major battle of the invasion was fought atThermopylae,where a small rearguard of Greeks, led by three hundred Spartans, held a crucial pass guarding the heart of Greece for several days; at the same timeGelon,tyrant of Syracuse, defeated the Carthaginian invasion at theBattle of Himera.[34]

The Persians were decisively defeated at sea by a primarily Athenian naval force at theBattle of Salamis,and on land in 479 BC at theBattle of Plataea.[35]The alliance against Persia continued, initially led by the SpartanPausaniasbut from 477 by Athens,[36]and by 460 Persia had been driven out of the Aegean.[37]During this long campaign, theDelian Leaguegradually transformed from a defensive alliance of Greek states into an Athenian empire, as Athens' growing naval power intimidated the other league states.[38]Athens ended its campaigns against Persia in 450, after a disastrous defeat in Egypt in 454, and the death ofCimonin action against the Persians on Cyprus in 450.[39]

As the Athenian fight against the Persian empire waned, conflict grew between Athens and Sparta. Suspicious of the increasing Athenian power funded by the Delian League, Sparta offered aid to reluctant members of the League to rebel against Athenian domination. These tensions were exacerbated in 462 BC when Athens sent a force to aid Sparta in overcoming ahelotrevolt, but this aid was rejected by the Spartans.[40]In the 450s, Athens took control of Boeotia, and won victories overAeginaand Corinth.[39]However, Athens failed to win a decisive victory, and in 447 lost Boeotia again.[39]Athens and Sparta signed theThirty Years' Peacein the winter of 446/5, ending the conflict.[39]

Despite the treaty, Athenian relations with Sparta declined again in the 430s, and in 431 BC thePeloponnesian Warbegan.[41]Thefirst phase of the warsaw a series of fruitless annual invasions of Attica by Sparta, while Athens successfully fought the Corinthian empire in northwest Greece and defended its own empire, despite aplaguewhich killed the leading Athenian statesmanPericles.[42]The war turned after Athenian victories led byCleonatPylosandSphakteria,[42]and Sparta sued for peace, but the Athenians rejected the proposal.[43]The Athenian failure to regain control of Boeotia atDeliumandBrasidas' successes in northern Greece in 424 improved Sparta's position after Sphakteria.[43]After the deaths of Cleon and Brasidas, the strongest proponents of war on each side,a peace treatywas negoitiated in 421 by the Athenian generalNicias.[44]

The peace did not last, however. In 418 BC allied forces of Athens and Argos were defeated by Sparta atMantinea.[45]In 415 Athens launched an ambitious naval expedition to dominate Sicily;[46]the expedition ended in disaster at the harbor ofSyracuse,with almost the entire army killed, and the ships destroyed.[47]Soon after the Athenian defeat in Syracuse, Athens' Ionian allies began to rebel against the Delian league, while Persia began to once again involve itself in Greek affairs on the Spartan side.[48]Initially the Athenian position continued relatively strong, with important victories atCyzicusin 410 andArginusaein 406.[49]However, in 405 the SpartanLysanderdefeated Athens in theBattle of Aegospotami,and began to blockade Athens' harbour;[50]driven by hunger, Athens sued for peace, agreeing to surrender their fleet and join the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League.[51]Following the Athenian surrender, Sparta installed an oligarchic regime, theThirty Tyrants,in Athens,[50]one of a number of Spartan-backed oligarchies which rose to power after the Peloponnesian war.[52]Spartan predominance did not last: after only a year, the Thirty had been overthrown.[53]

The first half of the fourth century saw the major Greek states attempt to dominate the mainland; none were successful, and their resulting weakness led to a power vacuum which would eventually be filled by Macedon under Philip II and then Alexander the Great.[54]In the immediate aftermath of the Peloponnesian war, Sparta attempted to extend their own power, leading Argos, Athens, Corinth, and Thebes to join against them.[55]Aiming to prevent any single Greek state gaining the dominance that would allow it to challenge Persia, the Persian king initially joined the alliance against Sparta, before imposing thePeace of Antalcidas( "King's Peace" ) which restored Persia's control over the Anatolian Greeks.[56]

By 371 BC, Thebes was in the ascendancy, defeating Sparta at theBattle of Leuctra,killing the Spartan kingCleombrotus I,and invading Laconia. Further Theban successes against Sparta in 369 led to Messenia gaining independence; Sparta never recovered from the loss of Messenia's fertile land and the helot workforce it provided.[57]The rising power of Thebes led Sparta and Athens to join forces; in 362 they were defeated by Thebes at theBattle of Mantinea.In the aftermath of Mantinea, none of the major Greek states were able to dominate. Though Thebes had won the battle, their general Epaminondas was killed, and they spent the following decades embroiled in wars with their neighbours; Athens, meanwhile, saw its second naval alliance, formed in 377, collapse in the mid-350s.[58]

The power vacuum in Greece after the Battle of Mantinea was filled by Macedon, underPhilip II.In 338 BC, he defeated a Greek alliance at theBattle of Chaeronea,and subsequently formed theLeague of Corinth.Philip planned to lead the League to invade Persia, but was murdered in 336 BC. His sonAlexander the Greatwas left to fulfil his father's ambitions.[59]After campaigns against Macedon's western and northern enemies, and those Greek states that had broken from the League of Corinth following the death of Philip, Alexander began his campaign against Persia in 334 BC.[60]He conquered Persia, defeatingDarius IIIat theBattle of Issusin 333 BC, and after theBattle of Gaugamelain 331 BC proclaimed himself king of Asia.[61]From 329 BC he led expeditions to Bactria and then India;[62]further plans to invade Arabia and North Africa were halted by his death in 323 BC.[63]

Hellenistic Greece

The period from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC until the death ofCleopatra,the last Macedonian ruler of Egypt, is known as the Hellenistic period. In the early part of this period, a new form of kingship developed based on Macedonian and Near Eastern traditions. The first Hellenistic kings were previously Alexander's generals, and took power in the period following his death, though they were not part of existing royal lineages and lacked historic claims to the territories they controlled.[64]The most important of these rulers in the decades after Alexander's death wereAntigonus Iand his sonDemetriusin Macedonia and the rest of Greece,Ptolemyin Egypt, andSeleucus Iin Syria and the former Persian empire;[65]smaller Hellenistic kingdoms included theAttalidsin Anatolia and theGreco-Bactrian kingdom.[66]

In the early part of the Hellenistic period, the exact borders of the Hellenistic kingdoms were not settled. Antigonus attempted to expand his territory by attacking the other successor kingdoms until they joined against him, and he was killed at theBattle of Ipsusin 301 BC.[67]His son Demetrius spent many years in Seleucid captivity, and his son,Antigonus II,only reclaimed the Macedonian throne around 276.[67]Meanwhile, the Seleucid kingdom gave up territory in the east to the Indian kingChandragupta Mauryain exchange for war elephants, and later lost large parts of Persia to theParthian Empire.[67]By the mid-third century, the kingdoms of Alexander's successors was mostly stable, though there continued to be disputes over border areas.[66]

During the Hellenistic period, the importance of "Greece proper" (the territory of modern Greece) within the Greek-speaking world declined sharply. The great capitals of Hellenistic culture wereAlexandriain thePtolemaic KingdomandAntiochin theSeleucid Empire.

The conquests of Alexander had numerous consequences for the Greek city-states. It greatly widened the horizons of the Greeks and led to a steady emigration of the young and ambitious to the new Greek empires in the east.[68]Many Greeks migrated to Alexandria, Antioch and the many other new Hellenistic cities founded in Alexander's wake, as far away as present-dayAfghanistanandPakistan,where theGreco-Bactrian Kingdomand theIndo-Greek Kingdomsurvived until the end of the first century BC.

The city-states within Greece formed themselves into two leagues; theAchaean League(including Thebes, Corinth and Argos) and theAetolian League(including Sparta and Athens). For much of the period until the Roman conquest, these leagues were at war, often participating in the conflicts between theDiadochi(the successor states to Alexander's empire).

The Antigonid Kingdom became involved in a war with the Roman Republic in the late 3rd century. Although theFirst Macedonian Warwas inconclusive, the Romans, in typical fashion, continued to fight Macedon until it was completely absorbed into the Roman Republic (by 149 BC). In the east, the unwieldy Seleucid Empire gradually disintegrated, although a rump survived until 64 BC, whilst the Ptolemaic Kingdom continued in Egypt until 30 BC when it too was conquered by the Romans. The Aetolian league grew wary of Roman involvement in Greece, and sided with the Seleucids in theRoman–Seleucid War;when the Romans were victorious, the league was effectively absorbed into the Republic. Although the Achaean league outlasted both the Aetolian league and Macedon, it was also soon defeated and absorbed by the Romans in 146 BC, bringing Greek independence to an end.

Roman Greece

The Greek peninsula came under Roman rule during the 146 BC conquest ofGreeceafter the Battle of Corinth.Macedoniabecame aRoman provincewhile southern Greece came under the surveillance of Macedonia'sprefect;however, some Greekpoleismanaged to maintain a partial independence and avoid taxation. TheAegean Islandswere added to this territory in 133 BC.Athensand other Greek cities revolted in 88 BC, and the peninsula was crushed by the Roman generalSulla.The Roman civil wars devastated the land even further, untilAugustusorganized the peninsula as the province ofAchaeain 27 BC.

Greece was a key eastern province of the Roman Empire, as theRoman culturehad long been in factGreco-Roman.TheGreek languageserved as alingua francain the East and inItaly,and many Greek intellectuals such asGalenwould perform most of their work inRome.

Geography

Regions

The territory of Greece is mountainous, and as a result, ancient Greece consisted of many smaller regions, each with its own dialect, cultural peculiarities, and identity. Regionalism and regional conflicts were prominent features of ancient Greece. Cities tended to be located in valleys between mountains, or on coastal plains, and dominated a certain area around them.

In the south lay thePeloponnese,consisting of the regions of Laconia (southeast), Messenia (southwest), Elis (west), Achaia (north), Korinthia (northeast), Argolis (east), and Arcadia (center). These names survive to the present day asregional units of modern Greece,though with somewhat different boundaries. Mainland Greece to the north, nowadays known asCentral Greece,consisted ofAetoliaandAcarnaniain the west,Locris,Doris,andPhocisin the center, while in the east layBoeotia,Attica,andMegaris.Northeast layThessaly,whileEpiruslay to the northwest. Epirus stretched from theAmbracian Gulfin the south to theCeraunian Mountainsand theAoosriver in the north, and consisted ofChaonia(north),Molossia(center), and Thesprotia (south). In the northeast corner wasMacedonia,[69]originally consistingLower Macedoniaand its regions, such asElimeia,Pieria,andOrestis.Around the time ofAlexander I of Macedon,theArgead kings of Macedonstarted to expand intoUpper Macedonia,lands inhabited by independentMacedoniantribes like theLyncestae,Orestaeand theElimiotaeand to the west, beyond theAxius river,intoEordaia,Bottiaea,Mygdonia,andAlmopia,regions settled by Thracian tribes.[70]To the north of Macedonia lay various non-Greek peoples such as thePaeoniansdue north, theThraciansto the northeast, and theIllyrians,with whom theMacedonianswere frequently in conflict, to the northwest.Chalcidicewas settled early on by southern Greek colonists and was considered part of the Greek world, while from the late 2nd millennium BC substantial Greek settlement also occurred on the eastern shores of theAegean,inAnatolia.

Colonies

During theArchaic period,the Greekpopulationgrew beyond the capacity of the limitedarable landof Greece proper,resulting in the large-scale establishment of colonieselsewhere: according to one estimate, the population of the widening area of Greek settlement increased roughly tenfold from 800 BC to 400 BC, from 800,000 to as many as7+1⁄2-10 million.[71]This was not simply for trade, but also to found settlements. TheseGreek colonieswere not, as Roman colonies were, dependent on their mother-city, but were independent city-states in their own right.[72]

Greeks settled outside of Greece in two distinct ways. The first was in permanent settlements founded by Greeks, which formed as independent poleis. The second form was in what historians refer to asemporia;trading posts which were occupied by both Greeks and non-Greeks and which were primarily concerned with the manufacture and sale of goods. Examples of this latter type of settlement are found atAl Minain the east andPithekoussaiin the west.[73]From about 750 BC the Greeks began 250 years of expansion, settling colonies in all directions. To the east, theAegeancoast ofAsia Minorwas colonized first, followed byCyprusand the coasts ofThrace,theSea of Marmaraand south coast of theBlack Sea.

Eventually, Greek colonization reached as far northeast as present-dayUkraineand Russia (Taganrog). To the west the coasts ofIllyria,Southern Italy(called "Magna Graecia") were settled, followed bySouthern France,Corsica,and even easternSpain.Greek colonies were also founded inEgyptandLibya.ModernSyracuse,Naples,MarseilleandIstanbulhad their beginnings as the Greek colonies Syracusae (Συράκουσαι), Neapolis (Νεάπολις), Massalia (Μασσαλία) andByzantion(Βυζάντιον). These colonies played an important role in the spread of Greek influence throughout Europe and also aided in the establishment of long-distance trading networks between the Greek city-states, boosting theeconomy of ancient Greece.

Politics and society

Political structure

Ancient Greece consisted of several hundred relatively independentcity-states(poleis). This was a situation unlike that in most other contemporary societies, which were eithertribalorkingdomsruling over relatively large territories. Undoubtedly, thegeography of Greece—divided and sub-divided by hills, mountains, and rivers—contributed to the fragmentary nature of ancient Greece. On the one hand, the ancient Greeks had no doubt that they were "one people"; they had the samereligion,same basic culture, and same language. Furthermore, the Greeks were very aware of their tribal origins; Herodotus was able to extensively categorise the city-states by tribe. Yet, although these higher-level relationships existed, they seem to have rarely had a major role in Greek politics. The independence of thepoleiswas fiercely defended; unification was something rarely contemplated by the ancient Greeks. Even when, during the second Persian invasion of Greece, a group of city-states allied themselves to defend Greece, the vast majority ofpoleisremained neutral, and after the Persian defeat, the allies quickly returned to infighting.[75]

Thus, the major peculiarities of the ancient Greek political system were its fragmentary nature (and that this does not particularly seem to have tribal origin), and the particular focus on urban centers within otherwise tiny states. The peculiarities of the Greek system are further evidenced by the colonies that they set up throughout the Mediterranean, which, though they might count a certain Greekpolisas their 'mother' (and remain sympathetic to her), were completely independent of the founding city.

Inevitably smallerpoleismight be dominated by larger neighbors, but conquest or direct rule by another city-state appears to have been quite rare. Instead thepoleisgrouped themselves into leagues, membership of which was in a constant state of flux. Later in the Classical period, the leagues would become fewer and larger, be dominated by one city (particularly Athens, Sparta and Thebes); and oftenpoleiswould be compelled to join under threat of war (or as part of a peace treaty). Even after Philip II of Macedon "conquered" the heartlands of ancient Greece, he did not attempt to annex the territory or unify it into a new province, but compelled most of thepoleisto join his ownCorinthian League.

Government and law

Initially many Greek city-states seem to have been petty kingdoms; there was often a city official carrying some residual, ceremonial functions of the king (basileus), e.g., thearchon basileusin Athens.[76]However, by the Archaic period and the first historical consciousness, most had already become aristocraticoligarchies.It is unclear exactly how this change occurred. For instance, in Athens, the kingship had been reduced to a hereditary, lifelong chief magistracy (archon) byc.1050 BC; by 753 BC this had become a decennial, elected archonship; and finally by 683 BC an annually elected archonship. Through each stage, more power would have been transferred to the aristocracy as a whole, and away from a single individual.

Inevitably, the domination of politics and concomitant aggregation of wealth by small groups of families was apt to cause social unrest in manypoleis.In many cities atyrant(not in the modern sense of repressive autocracies), would at some point seize control and govern according to their own will; often a populist agenda would help sustain them in power. In a system wracked withclass conflict,government by a 'strongman' was often the best solution.

Athens fell under a tyranny in the second half of the 6th century BC. When this tyranny was ended, the Athenians foundedthe world's first democracyas a radical solution to prevent the aristocracy regaining power. Acitizens' assembly(theEcclesia), for the discussion of city policy, had existed since the reforms ofDracoin 621 BC; all citizens were permitted to attend after the reforms ofSolon(early 6th century), but the poorest citizens could not address the assembly or run for office. With the establishment of the democracy, the assembly became thede juremechanism of government; all citizens had equal privileges in the assembly. However, non-citizens, such asmetics(foreigners living in Athens) orslaves,had no political rights at all.

After the rise of democracy in Athens, other city-states founded democracies. However, many retained more traditional forms of government. As so often in other matters, Sparta was a notable exception to the rest of Greece, ruled through the whole period by not one, but two hereditary monarchs. This was a form ofdiarchy.TheKings of Spartabelonged to the Agiads and the Eurypontids, descendants respectively ofEurysthenesandProcles.Both dynasties' founders were believed to be twin sons ofAristodemus,aHeraclidruler. However, the powers of these kings were held in check by both a council of elders (theGerousia) and magistrates specifically appointed to watch over the kings (theEphors).

Social structure

Only free, land-owning, native-born men could be citizens entitled to the full protection of the law in a city-state. In most city-states, unlike the situation inRome,social prominence did not allow special rights. Sometimes families controlled public religious functions, but this ordinarily did not give any extra power in the government. In Athens, the population was divided into four social classes based on wealth. People could change classes if they made more money. In Sparta, all male citizens were calledhomoioi,meaning "peers". However, Spartan kings, who served as the city-state's dual military and religious leaders, came from two families.[77]

Slavery

Slaves had no power or status. Slaves had the right to have a family and own property, subject to their master's goodwill and permission, but they had no political rights. By 600 BC,chattel slaveryhad spread in Greece. By the 5th century BC, slaves made up one-third of the total population in some city-states. Between 40–80% of the population ofClassical Athenswere slaves.[78]Slaves outside of Sparta almost never revolted because they were made up of too many nationalities and were too scattered to organize. However, unlike laterWestern culture,the ancient Greeks did not think in terms ofrace.[79]

Most families owned slaves as household servants and laborers, and even poor families might have owned a few slaves. Owners were not allowed to beat or kill their slaves. Owners often promised to free slaves in the future to encourage slaves to work hard. Unlike in Rome,freedmendid not become citizens. Instead, they were mixed into the population ofmetics,which included people from foreign countries or other city-states who were officially allowed to live in the state.

City-states legally owned slaves. These public slaves had a larger measure of independence than slaves owned by families, living on their own and performing specialized tasks. In Athens, public slaves were trained to look out forcounterfeit coinage,while temple slaves acted as servants of the temple'sdeityandScythianslaves were employed in Athens as a police force corralling citizens to political functions.

Sparta had a special type of slaves calledhelots.Helots wereMesseniansenslaved en masse during theMessenian Warsby the state and assigned to families where they were forced to stay. Helots raised food and did household chores so that women could concentrate on raising strong children while men could devote their time to training ashoplites.Their masters treated them harshly, and helotsrevoltedagainst their masters several times. In 370/69 BC, as a result ofEpaminondas' liberation of Messenia from Spartan rule, the helot system there came to an end and the helots won their freedom.[80]However, it did continue to persist in Laconia until the 2nd century BC.

Education

For most of Greek history, education was private, except in Sparta. During the Hellenistic period, some city-states establishedpublic schools.Only wealthy families could afford a teacher. Boys learned how to read, write and quote literature. They also learned to sing and play one musical instrument and were trained as athletes for military service. They studied not for a job but to become an effective citizen. Girls also learned to read, write and do simple arithmetic so they could manage the household. They almost never received education after childhood.[81]

Boys went to school at the age of seven, or went to the barracks, if they lived in Sparta. The three types of teachings were: grammatistes for arithmetic, kitharistes for music and dancing, and Paedotribae for sports.

Boys from wealthy families attending the private school lessons were taken care of by apaidagogos,a household slave selected for this task who accompanied the boy during the day. Classes were held in teachers' private houses and included reading, writing, mathematics, singing, and playing the lyre and flute. When the boy became 12 years old the schooling started to include sports such as wrestling, running, and throwing discus and javelin. In Athens, some older youths attended academy for the finer disciplines such as culture, sciences, music, and the arts. The schooling ended at age 18, followed by military training in the army usually for one or two years.[82]

Only a small number of boys continued their education after childhood, as in the Spartanagoge.A crucial part of a wealthy teenager's education was a mentorship with an elder, which in a few places and times may have includedpederasty.[citation needed]The teenager learned by watching his mentor talking about politics in theagora,helping him perform his public duties, exercising with him in the gymnasium and attendingsymposiawith him. The richest students continued their education by studying with famous teachers. Some of Athens' greatest such schools included theLyceum(the so-calledPeripatetic schoolfounded byAristotleofStageira) and thePlatonic Academy(founded byPlatoof Athens). The education system of the wealthy ancient Greeks is also calledPaideia.[citation needed]

Economy

At its economic height in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, the free citizenry ofClassical Greecerepresented perhaps the most prosperous society in the ancient world, some economic historians considering Greece one of the most advanced pre-industrial economies. In terms of wheat, wages reached an estimated 7–12 kg daily for an unskilled worker in urban Athens, 2–3 times the 3.75 kg of an unskilled rural labourer in Roman Egypt, though Greek farm incomes too were on average lower than those available to urban workers.[83]

While slave conditions varied widely, the institution served to sustain the incomes of the free citizenry: an estimate of economic development drawn from the latter (or derived from urban incomes alone) is therefore likely to overstate the true overall level despite widespread evidence for high living standards.

Warfare

At least in the Archaic Period, the fragmentary nature of ancient Greece, with many competing city-states, increased the frequency of conflict but conversely limited the scale of warfare. Unable to maintain professional armies, the city-states relied on their own citizens to fight. This inevitably reduced the potential duration of campaigns, as citizens would need to return to their own professions (especially in the case of, for example, farmers). Campaigns would therefore often be restricted to summer. When battles occurred, they were usually set piece and intended to be decisive. Casualties were slight compared to later battles, rarely amounting to more than five percent of the losing side, but the slain often included the most prominent citizens and generals who led from the front.

The scale and scope of warfare in ancient Greece changed dramatically as a result of theGreco-Persian Wars.To fight the enormous armies of theAchaemenid Empirewas effectively beyond the capabilities of a single city-state. The eventual triumph of the Greeks was achieved by alliances of city-states (the exact composition changing over time), allowing the pooling of resources and division of labor. Although alliances between city-states occurred before this time, nothing on this scale had been seen before. The rise ofAthensandSpartaas pre-eminent powers during this conflict led directly to thePeloponnesian War,which saw further development of the nature of warfare, strategy and tactics. Fought between leagues of cities dominated by Athens and Sparta, the increased manpower and financial resources increased the scale and allowed the diversification of warfare. Set-piece battles during the Peloponnesian war proved indecisive and instead there was increased reliance on attritionary strategies, naval battles and blockades and sieges. These changes greatly increased the number of casualties and the disruption of Greek society.

Athens owned one of the largest war fleets in ancient Greece. It had over 200triremeseach powered by 170 oarsmen who were seated in 3 rows on each side of the ship. The city could afford such a large fleet—it had over 34,000 oarsmen—because it owned a lot of silver mines that were worked by slaves.

According toJosiah Ober,Greek city-states faced approximately a one-in-three chance of destruction during the archaic and classical period.[84]

Culture

Philosophy

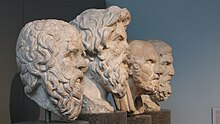

Ancient Greek philosophy focused on the role ofreasonandinquiry.In many ways, it had an important influence on modernphilosophy,as well as modern science. Clear unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient Greek andHellenistic philosophers,to medievalMuslim philosophersandIslamic scientists,to the EuropeanRenaissanceandEnlightenment,to the secular sciences of the modern day.

Neither reason nor inquiry began with the ancient Greeks. Defining the difference between the Greek quest for knowledge and the quests of the elder civilizations, such as theancient EgyptiansandBabylonians,has long been a topic of study by theorists of civilization.

The first known philosophers of Greece were thepre-Socratics,who attempted to provide naturalistic, non-mythical descriptions of the world. They were followed bySocrates,one of the first philosophers based in Athens duringits golden agewhose ideas, despite being known by second-hand accounts instead of writings of his own, laid the basis of Western philosophy. Socrates' disciplePlato,who wroteThe Republicand established a radical difference between ideas and the concrete world, and Plato's discipleAristotle,who wrote extensively about nature and ethics, are also immensely influential in Western philosophy to this day. The laterHellenistic philosophy,also originating in Greece, is defined by names such asAntisthenes(cynicism),Zeno of Citium(stoicism) andPlotinus(Neoplatonism).

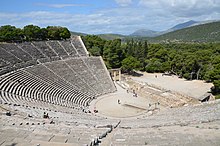

Literature and theatre

The earliest Greek literature was poetry and was composed for performance rather than private consumption.[85]The earliest Greek poet known isHomer,although he was certainly part of an existing tradition of oral poetry.[86]Homer's poetry, though it was developed around the same time that the Greeks developed writing, would have been composed orally; the first poet to certainly compose their work in writing wasArchilochus,alyric poetfrom the mid-seventh century BC.[87]Tragedydeveloped around the end of the archaic period, taking elements from across the pre-existing genres of late archaic poetry.[88]Towards the beginning of the classical period, comedy began to develop—the earliest date associated with the genre is 486 BC, when a competition for comedy became an official event at theCity Dionysiain Athens, though the first preserved ancient comedy isAristophanes'Acharnians,produced in 425.[89]

Like poetry, Greek prose had its origins in the archaic period, and the earliest writers of Greek philosophy, history, and medical literature all date to the sixth century BC.[90]Prose first emerged as the writing style adopted by thepresocraticphilosophersAnaximanderandAnaximenes—thoughThales of Miletus,considered the first Greek philosopher, apparently wrote nothing.[91]Prose as a genre reached maturity in the classical era,[90]and the major Greek prose genres—philosophy, history, rhetoric, and dialogue—developed in this period.[92]

The Hellenistic period saw the literary centre of the Greek world move from Athens, where it had been in the classical period, to Alexandria. At the same time, other Hellenistic kings such as theAntigonidsand theAttalidswere patrons of scholarship and literature, turningPellaandPergamonrespectively into cultural centres.[93]It was thanks to this cultural patronage by Hellenistic kings, and especially the Museum at Alexandria, that so much ancient Greek literature has survived.[94]TheLibrary of Alexandria,part of the Museum, had the previously unenvisaged aim of collecting together copies of all known authors in Greek. Almost all of the surviving non-technical Hellenistic literature is poetry,[94]and Hellenistic poetry tended to be highly intellectual,[95]blending different genres and traditions, and avoiding linear narratives.[96]The Hellenistic period also saw a shift in the ways literature was consumed—while in the archaic and classical periods literature had typically been experienced in public performance, in the Hellenistic period it was more commonly read privately.[97]At the same time, Hellenistic poets began to write for private, rather than public, consumption.[98]

With Octavian's victory at Actium in 31 BC, Rome began to become a major centre of Greek literature, as important Greek authors such asStraboandDionysius of Halicarnassuscame to Rome.[99]The period of greatest innovation in Greek literature under Rome was the "long second century" from approximately 80 AD to around 230 AD.[100]This innovation was especially marked in prose, with the development of the novel and a revival of prominence for display oratory both dating to this period.[100]

Music and dance

In Ancient Greek society, music was ever-present and considered a fundamental component of civilisation.[101]It was an important part of public religious worship,[102]private ceremonies such as weddings and funerals,[103]and household entertainment.[104]Men sang and played music at thesymposium;[105]both men and women sang at work; and children's games involved song and dance.[106]

Ancient Greek music was primarily vocal, sung either by a solo singer or a chorus, and usually accompanied by an instrument; purely instrumental music was less common.[107]The Greeks used stringed instruments, including lyres, harps, and lutes;[108]and wind instruments, of which the most important was theaulos,areed instrument.[109]Percussion instruments played a relatively unimportant role supporting stringed and wind instruments, and were used in certain religious cults.[110]

Science and technology

Ancient Greek mathematics contributed many important developments to the field ofmathematics,including the basic rules ofgeometry,the idea offormal mathematical proof,and discoveries innumber theory,mathematical analysis,applied mathematics,and approached close to establishingintegral calculus.The discoveries of several Greek mathematicians, includingPythagoras,Euclid,andArchimedes,are still used in mathematical teaching today.

The Greeks developed astronomy, which they treated as a branch of mathematics, to a highly sophisticated level. The first geometrical, three-dimensional models to explain the apparent motion of the planets were developed in the 4th century BC byEudoxus of CnidusandCallippus of Cyzicus.Their younger contemporaryHeraclides Ponticusproposed that the Earth rotates around its axis. In the 3rd century BC,Aristarchus of Samoswas the first to suggest aheliocentricsystem. Archimedes in his treatiseThe Sand Reckonerrevives Aristarchus' hypothesis that"the fixed stars and the Sun remain unmoved, while the Earth revolves about the Sun on the circumference of a circle".Otherwise, only fragmentary descriptions of Aristarchus' idea survive.[111]Eratosthenes,using the angles of shadows created at widely separated regions, estimated thecircumference of the Earthwith great accuracy.[112]In the 2nd century BCHipparchus of Niceamade a number of contributions, including the first measurement ofprecessionand the compilation of the first star catalog in which he proposed the modern system ofapparent magnitudes.

TheAntikythera mechanism,a device for calculating the movements of planets, dates from about 80 BC and was the first ancestor of the astronomicalcomputer.It was discovered in an ancient shipwreck off the Greek island ofAntikythera,betweenKytheraandCrete.The device became famous for its use of adifferential gear,previously believed to have been invented in the 16th century, and the miniaturization and complexity of its parts, comparable to a clock made in the 18th century. The original mechanism is displayed in the Bronze collection of theNational Archaeological Museum of Athens,accompanied by a replica.

The ancient Greeks also made important discoveries in the medical field. Hippocrates was aphysicianof the Classical period, and is considered one of the most outstanding figures in thehistory of medicine.He is referred to as the "father of medicine"[113][114]in recognition of his lasting contributions to the field as the founder of the Hippocratic school of medicine. This intellectual school revolutionizedmedicine in ancient Greece,establishing it as a discipline distinct from other fields that it had traditionally been associated with (notablytheurgyandphilosophy), thus making medicine a profession.[115][116]

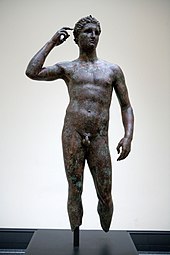

Art and architecture

The art of ancient Greece has exercised an enormous influence on the culture of many countries from ancient times to the present day, particularly in the areas ofsculptureandarchitecture.In the West, the art of theRoman Empirewas largely derived from Greek models. In the East, Alexander the Great's conquests initiated several centuries of exchange between Greek, Central Asian andIndiancultures, resulting inGreco-Buddhist art,with ramifications as far asJapan.Following theRenaissancein Europe, thehumanistaesthetic and the high technical standards of Greek art inspired generations of European artists. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the Western world.

Religion

Religion was a central part of ancient Greek life.[117]Though the Greeks of different cities andtribesworshipped similar gods, religious practices were not uniform and the gods were thought of differently in different places. The Greeks werepolytheistic,worshipping many gods, but as early as the sixth century BC a pantheon oftwelve Olympiansbegan to develop.[118]Greek religion was influenced by the practices of the Greeks' near eastern neighbours at least as early as the archaic period, and by the Hellenistic period this influence was seen in both directions.[119]

The most important religious act in ancient Greece wasanimal sacrifice,most commonly of sheep and goats.[120]Sacrifice was accompanied by public prayer,[121]and prayer and hymns were themselves a major part of ancient Greek religious life.[122]

Legacy

The civilization of ancient Greece has been immensely influential on language, politics, educational systems, philosophy, science, and the arts. It became theLeitkulturof theRoman Empireto the point of marginalizing nativeItalictraditions. AsHoraceput it,

- Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artis / intulit agresti Latio(Epistulae2.1.156f.)

- Captive Greece took captive her uncivilised conqueror and instilled her arts in rusticLatium.

Via the Roman Empire, Greek culture came to be foundational toWestern culturein general. TheByzantine Empireinherited Classical Greek-Hellenistic culture directly, without Latin intermediation, and the preservation of Classical Greek learning in medieval Byzantine tradition further exerted a strong influence on theSlavsand later on theIslamic Golden Ageand the Western EuropeanRenaissance.A modern revival of Classical Greek learning took place in theNeoclassicismmovement in 18th- and 19th-century Europe and the Americas.

See also

- List of ancient Greek writers

- Outline of ancient Greece

- Outline of ancient Egypt

- Outline of ancient Rome

- Outline of classical studies

- Modern influence of Ancient Greece

- List of archaeologically attested women from the ancient Mediterranean region

Notes

- ^Though this excludes Greek city-states free from Alexander's jurisdiction in the western Mediterranean, around the Black Sea, Cyprus, and Cyrenaica

References

Notes

- ^Carol G. Thomas (1988).Paths from ancient Greece.Brill. pp. 27–50.ISBN978-90-04-08846-7.

- ^Maura Ellyn; Maura McGinnis (2004).Greece: A Primary Source Cultural Guide.The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 8.ISBN978-0-8239-3999-2.

- ^John E. Findling; Kimberly D. Pelle (2004).Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement.Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 23.ISBN978-0-313-32278-5.

- ^Wayne C. Thompson; Mark H. Mullin (1983).Western Europe, 1983.Stryker-Post Publications. p. 337.ISBN9780943448114.

for ancient Greece was the cradle of Western culture...

- ^Osborne, Robin (2009).Greece in the Making: 1200–479 BC.London: Routledge. p. xvii.

- ^Shapiro 2007,p. 1

- ^Shapiro 2007,pp. 2–3

- ^Hadas, Moses (1950).A History of Greek Literature.Columbia University Press. p. 273.ISBN978-0-231-01767-1.

- ^Marincola (2001),p. 59

- ^Roberts (2011),p. 2

- ^Sparks (1998),p. 58

- ^Asheri, Lloyd & Corcella (2007)

- ^Cameron (2004),p. 156

- ^Grant, Michael (1995).Greek and Roman historians: information and misinformation.Routledge. p. 74.ISBN978-0-415-11770-8.

- ^Martin 2013,p. 65

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 67–68

- ^Martin 2013,p. 103

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 69–70

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 73–4

- ^Martin 2013,p. 108

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 109–110

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 112–113

- ^Martin 2013,p. 96

- ^Martin 2013,p. 98

- ^Osborne 2009,p. 270

- ^Hammond 1982,p. 356

- ^Osborne 2009,p. 275

- ^Osborne 2009,p. 271

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 126–27

- ^abMartin 2013,p. 127

- ^Martin 2013,p. 128

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 128–29

- ^abcMartin 2013,p. 131

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 131–33

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 134–36

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 137–38

- ^Martin 2013,p. 140

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 137–41

- ^abcdMartin 2013,p. 147

- ^Martin 2013,p. 142

- ^Martin 2013,p. 149

- ^abHornblower 2011,p. 160

- ^abHornblower 2011,p. 162

- ^Hornblower 2011,p. 163

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 198–99

- ^Martin 2013,p. 200

- ^Hornblower 2011,p. 177

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 202–03

- ^Hornblower 2011,pp. 186–89

- ^abMartin 2013,p. 205

- ^Hornblower 2011,p. 189

- ^Hornblower 2011,p. 203

- ^Hornblower 2011,p. 219

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 221, 226

- ^Martin 2013,p. 224

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 224–225

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 225–226

- ^Martin 2013,p. 226

- ^Martin 2013,p. 221

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 243–245

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 245–247

- ^Martin 2013,p. 248

- ^Martin 2013,p. 250

- ^Martin 2013,p. 253.

- ^Martin 2013,pp. 254–255.

- ^abMartin 2013,p. 256.

- ^abcMartin 2013,p. 255.

- ^Alexander's Gulf outpost uncovered.BBC News. 7 August 2007.

- ^"Macedonia".Encyclopædia Britannica.Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 8 December 2008.Retrieved3 November2008.

- ^The Cambridge Ancient History: The fourth century B.C.edited by D.M. Lewis et al. I E S Edwards, Cambridge University Press, D.M. Lewis, John Boardman,Cyril John Gadd,Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond, 2000,ISBN0-521-23348-8,pp. 723–24.

- ^"Population of the Greek city-states".Archived fromthe originalon 5 March 2007.

- ^Boardman & Hammond 1982,p. xiii

- ^Antonaccio 2007,p. 203

- ^Ruden, Sarah (2003).Lysistrata.Hackett Publishing, p. 80.ISBN0-87220-603-3.

- ^Holland, T.Persian Fire,Abacus, pp. 363–70ISBN978-0-349-11717-1

- ^Holland T.Persian Fire,p. 94ISBN978-0-349-11717-1

- ^Powell, Anton (2017).A Companion to Sparta.John Wiley & Sons. p. 187.ISBN9781119072379.Retrieved4 July2022.

- ^Slavery in Ancient GreeceArchived1 December 2008 at theWayback Machine.Britannica Student Encyclopædia.

- ^Painter, Nell (2010).The History of White People.New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p.5.ISBN978-0-393-04934-3.

- ^Cartledge, Paul (2002).The Spartans: An Epic History.Pan Macmillan. p. 67.

- ^Bloomer, W. Martin (2016).A Companion to Ancient Education.Malden, MA: Willey-Blackwell. p. 305.ISBN978-1-118-99741-3.

- ^Angus Konstam: "Historical Atlas of Ancient Greece", pp. 94–95. Thalamus publishing, UK, 2003,ISBN1-904668-16-X

- ^W. Schiedel, "Real slave prices and the relative cost of slave labor in the Greco-Roman world",Ancient Society,vol. 35, 2005, p 12.

- ^Ober, Josiah (2010).Democracy and Knowledge.Princeton University Press. pp. 81–2.ISBN978-0-691-14624-9.

- ^Power 2016,p. 58

- ^Kirk 1985,p. 44

- ^Kirk 1985,p. 45

- ^Power 2016,p. 60

- ^Handley 1985,p. 355

- ^abMcGlew 2016,p. 79

- ^McGlew 2016,p. 81

- ^McGlew 2016,p. 84

- ^Mori 2016,p. 93

- ^abBulloch 1985,p. 542

- ^Bulloch 1985,pp. 542–43

- ^Mori 2016,p. 99

- ^Mori 2016,p. 98

- ^Bulloch 1985,p. 543

- ^Bowersock 1985,pp. 642–43

- ^abKönig 2016,p. 113

- ^West 1994,pp. 1, 13.

- ^West 1994,p. 14.

- ^West 1994,p. 21.

- ^West 1994,p. 24.

- ^West 1994,p. 25.

- ^West 1994,pp. 27–28.

- ^West 1994,p. 39.

- ^West 1994,p. 48.

- ^West 1994,p. 81.

- ^West 1994,p. 122.

- ^Pedersen,Early Physics and Astronomy,pp. 55–56

- ^Pedersen,Early Physics and Astronomy,pp. 45–47

- ^Grammaticos, P.C.; Diamantis, A. (2008). "Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and his teacher Democritus".Hellenic Journal of Nuclear Medicine.11(1): 2–4.PMID18392218.

- ^Hippocrates,Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Microsoft Corporation.Archived31 October 2009.

- ^Garrison, Fielding H. (1966).History of Medicine.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. pp. 92–93.

- ^Nuland, Sherwin B. (1988).Doctors.Knopf. p.5.ISBN978-0-394-55130-2.

- ^Ogden 2007,p. 1.

- ^Dowden 2007,p. 41.

- ^Noegel 2007,pp. 21–22.

- ^Bremmer 2007,pp. 132–134.

- ^Furley 2007,p. 121.

- ^Furley 2007,p. 117.

Bibliography

- Antonaccio, Carla M. (2007). "Colonization: Greece on the Move 900–480". In Shapiro, H.A. (ed.).The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Asheri, David; Lloyd, Alan; Corcella, Aldo (2007).A Commentary on Herodotus, Books 1–4.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-814956-9.

- Boardman, John; Hammond, N.G.L. (1982). "Preface". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N.G.L (eds.).The Cambridge Ancient History - Volume 3, part 3.Vol. III (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bowersock, G.W. (1985). "The literature of the Empire". In Easterling, P.E.; Knox, Bernard M.W. (eds.).The Cambridge History of Classical Literature.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bremmer, Jan M. (2007). "Greek Normative Animal Sacrifice". In Ogden, Daniel (ed.).A Companion to Greek Religion.Blackwell.

- Bulloch, A.W. (1985). "Hellenistic Poetry". In Easterling, P.E.; Knox, Bernard M.W. (eds.).The Cambridge History of Classical Literature.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cameron, Alan (2004).Greek Mythography in the Roman World.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-803821-4.

- Dowden, Ken (2007). "Olympian Gods, Olympian Pantheon". In Ogden, Daniel (ed.).A Companion to Greek Religion.Blackwell.

- Furley, William D. (2007). "Prayers and Hymns". In Ogden, Daniel (ed.).A Companion to Greek Religion.Blackwell.

- Hammond, N.G.L (1982). "The Peloponnese". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N.G.L (eds.).The Cambridge Ancient History.Vol. III.iii (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Handley, E.W. (1985). "Comedy". In Easterling, P.E.; Knox, Bernard M.W. (eds.).The Cambridge History of Classical Literature.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hornblower, Simon (2011).The Greek World: 479–323 BC(4 ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kirk, G.S. (1985). "Homer". In Easterling, P.E.; Knox, Bernard M.W. (eds.).The Cambridge History of Classical Literature.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- König, Jason (2016). "Literature in the Roman World". In Hose, Martin; Schenker, David (eds.).A Companion to Greek Literature.John Wiley & Sons.

- Marincola, John (2001).Greek Historians.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-922501-9.

- Martin, Thomas R. (2013).Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times(2 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press.

- McGlew, James (2016). "Literature in the Classical Age of Greece". In Hose, Martin; Schenker, David (eds.).A Companion to Greek Literature.John Wiley & Sons.

- Mori, Anatole (2016). "Literature in the Hellenistic World". In Hose, Martin; Schenker, David (eds.).A Companion to Greek Literature.John Wiley & Sons.

- Noegel, Scott B. (2007). "Greek Religion and the Ancient Near East". In Ogden, Daniel (ed.).A Companion to Greek Religion.Blackwell.

- Ogden, Daniel (2007). "Introduction". In Ogden, Daniel (ed.).A Companion to Greek Religion.Blackwell.

- Power, Timothy (2016). "Literature in the Archaic Age". In Hose, Martin; Schenker, David (eds.).A Companion to Greek Literature.John Wiley & Sons.

- Roberts, Jennifer T. (2011).Herodotus: a Very Short Introduction.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-957599-2.

- Shapiro, H.A. (2007). "Introduction". In Shapiro, H.A. (ed.).The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sparks, Kenton L. (1998).Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic Sentiments and their Expression in the Hebrew Bible.Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.ISBN978-1-57506-033-0.

- West, M. L. (1994).Ancient Greek Music.Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Further reading

- Shanks, Michael (1996).Classical Archaeology of Greece.London: Routledge.ISBN0-203-17197-7.

- Brock, Roger, and Stephen Hodkinson, eds. 2000.Alternatives to Athens: Varieties of political organization and community in ancient Greece.Oxford and New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Cartledge, Paul, Edward E. Cohen, and Lin Foxhall. 2002.Money, labour and land: Approaches to the economies of ancient Greece.London and New York: Routledge.

- Cohen, Edward. 1992.Athenian economy and society: A banking perspective.Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Hurwit, Jeffrey. 1987.The art and culture of early Greece, 1100–480 B.C.Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.

- Kinzl, Konrad, ed. 2006.A companion to the Classical Greek world.Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Morris, Ian, ed. 1994.Classical Greece: Ancient histories and modern archaeologies.Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Pomeroy, Sarah, Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts. 2008.Ancient Greece: A political, social, and cultural history.2d ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Rhodes, Peter J. 2006.A history of the Classical Greek world: 478–323 BC.Blackwell History of the Ancient World. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Whitley, James. 2001.The archaeology of ancient Greece.Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge Univ. Press.

External links

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization—Greece Secrets of the Past

- Ancient Greecewebsite from theBritish Museum

- Economic history of ancient Greece(archived 2 May 2006)

- The Greek currency history

- Limenoscope,an ancient Greek ports database (archived 11 May 2011)

- The Ancient Theatre Archive,Greek and Roman theatre architecture

- Illustrated Greek History,Janice Siegel, Department of Classics,Hampden–Sydney College,Virginia