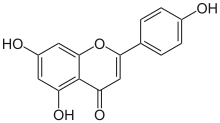

Apigenin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | |

| Other names

Apigenine; Chamomile; Apigenol; Spigenin; Versulin; C.I. Natural Yellow 1

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.540 |

| KEGG | |

PubChemCID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard(EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H10O5 | |

| Molar mass | 270.240g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Yellow crystalline solid |

| Melting point | 345 to 350 °C (653 to 662 °F; 618 to 623 K) |

| UV-vis(λmax) | 267, 296sh, 336 nm in methanol[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in theirstandard state(at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Apigenin(4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone), found in many plants, is anatural productbelonging to theflavoneclass that is theaglyconeof several naturally occurringglycosides.It is a yellow crystalline solid that has been used to dye wool.

Sources in nature[edit]

Apigenin is found in many fruits and vegetables, butparsley,celery,celeriac,andchamomiletea are the most common sources.[3]Apigenin is particularly abundant in the flowers of chamomile plants, constituting 68% of totalflavonoids.[4]Dried parsley can contain about 45mgapigenin/gram of the herb, and dried chamomile flower about 3–5 mg/gram.[5]The apigenin content of fresh parsley is reportedly 215.5 mg/100 grams, which is much higher than the next highest food source, green celery hearts providing 19.1 mg/100 grams.[6]

Pharmacology[edit]

Apigenin competitively binds to the benzodiazepine site onGABAAreceptors.[7]There exist conflicting findings regarding how apigenin interacts with this site.[8][9]

Biosynthesis[edit]

Apigenin is biosynthetically derived from the generalphenylpropanoid pathwayand the flavone synthesis pathway.[10]The phenylpropanoid pathway starts from the aromatic amino acids L-phenylalanine or L-tyrosine, both products of theShikimate pathway.[11]When starting from L-phenylalanine, first the amino acid is non-oxidatively deaminated byphenylalanine ammonia lyase(PAL) to make cinnamate, followed by oxidation at theparaposition bycinnamate 4-hydroxylase(C4H) to producep-coumarate. As L-tyrosine is already oxidized at theparaposition, it skips this oxidation and is simply deaminated bytyrosine ammonia lyase(TAL) to arrive atp-coumarate.[12]To complete the general phenylpropanoid pathway,4-coumarate CoA ligase(4CL) substitutes coenzyme A (CoA) at the carboxy group ofp-coumarate. Entering the flavone synthesis pathway, the type IIIpolyketide synthaseenzymechalcone synthase(CHS) uses consecutive condensations of three equivalents ofmalonyl CoAfollowed by aromatization to convertp-coumaroyl-CoA tochalcone.[13]Chalcone isomerase(CHI) then isomerizes the product to close the pyrone ring to makenaringenin.Finally, a flavanone synthase (FNS) enzyme oxidizes naringenin to apigenin.[14]Two types of FNS have previously been described; FNS I, a soluble enzyme that uses 2-oxogluturate, Fe2+,and ascorbate as cofactors and FNS II, a membrane bound, NADPH dependent cytochrome p450 monooxygenase.[15]

Glycosides[edit]

The naturally occurringglycosidesformed by the combination of apigenin with sugars include:

- Apiin(apigenin 7-O-apioglucoside), isolated fromparsley[16]and celery

- Apigetrin(apigenin 7-glucoside), found indandelion coffee

- Vitexin(apigenin 8-C-glucoside)

- Isovitexin(apigenin 6-C-glucoside)

- Rhoifolin(apigenin 7-O-neohesperidoside)

- Schaftoside(apigenin 6-C-glucoside 8-C-arabinoside)

In diet[edit]

Some foods contain relatively high amounts of apigenin:[17]

| Product | Apigenin (milligrams per 100 grams) |

|---|---|

| Dried parsley | 4500[5] |

| Chamomile | 300–500 |

| Parsley | 215.5 |

| Celery hearts, green | 19.1 |

| Rutabagas, raw | 4 |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Merck Index,11th Edition,763.

- ^The Systematic Identification of Flavonoids. Mabry et al, 1970, page 81

- ^The compound in the Mediterranean diet that makes cancer cells 'mortal'Emily Caldwell, Medical Express, May 20, 2013.

- ^Venigalla M, Gyengesi E, Münch G (August 2015)."Curcumin and Apigenin – novel and promising therapeutics against chronic neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease".Neural Regeneration Research.10(8): 1181–5.doi:10.4103/1673-5374.162686.PMC4590215.PMID26487830.

- ^abShankar E, Goel A, Gupta K, Gupta S (2017)."Plant flavone apigenin: An emerging anticancer agent".Current Pharmacology Reports.3(6): 423–446.doi:10.1007/s40495-017-0113-2.PMC5791748.PMID29399439.

- ^Delage, PhD, Barbara (November 2015)."Flavonoids".Corvallis, Oregon:Linus Pauling Institute,Oregon State University.Retrieved2021-01-26.

- ^Viola, H.; Wasowski, C.; Levi de Stein, M.; Wolfman, C.; Silveira, R.; Dajas, F.; Medina, J. H.; Paladini, A. C. (June 1995)."Apigenin, a component of Matricaria recutita flowers, is a central benzodiazepine receptors-ligand with anxiolytic effects".Planta Medica.61(3): 213–216.doi:10.1055/s-2006-958058.ISSN0032-0943.PMID7617761.

- ^Dekermend gian, K.; Kahnberg, P.; Witt, M. R.; Sterner, O.; Nielsen, M.; Liljefors, T. (1999-10-21)."Structure-activity relationships and molecular modeling analysis of flavonoids binding to the benzodiazepine site of the rat brain GABA(A) receptor complex".Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.42(21): 4343–4350.doi:10.1021/jm991010h.ISSN0022-2623.PMID10543878.

- ^Avallone, R.; Zanoli, P.; Puia, G.; Kleinschnitz, M.; Schreier, P.; Baraldi, M. (2000-06-01)."Pharmacological profile of apigenin, a flavonoid isolated from Matricaria chamomilla".Biochemical Pharmacology.59(11): 1387–1394.doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00264-1.ISSN0006-2952.PMID10751547.

- ^Forkmann, G. (January 1991)."Flavonoids as Flower Pigments: The Formation of the Natural Spectrum and its Extension by Genetic Engineering".Plant Breeding.106(1): 1–26.doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.1991.tb00474.x.ISSN0179-9541.

- ^Herrmann KM (January 1995)."The shikimate pathway as an entry to aromatic secondary metabolism".Plant Physiology.107(1): 7–12.doi:10.1104/pp.107.1.7.PMC161158.PMID7870841.

- ^Lee H, Kim BG, Kim M, Ahn JH (September 2015)."Biosynthesis of Two Flavones, Apigenin and Genkwanin, in Escherichia coli".Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology.25(9): 1442–8.doi:10.4014/jmb.1503.03011.PMID25975614.

- ^Austin MB, Noel JP (February 2003). "The chalcone synthase superfamily of type III polyketide synthases".Natural Product Reports.20(1): 79–110.CiteSeerX10.1.1.131.8158.doi:10.1039/b100917f.PMID12636085.

- ^Martens S, Forkmann G, Matern U, Lukacin R (September 2001). "Cloning of parsley flavone synthase I".Phytochemistry.58(1): 43–6.doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00191-1.PMID11524111.

- ^Leonard E, Yan Y, Lim KH, Koffas MA (December 2005)."Investigation of two distinct flavone synthases for plant-specific flavone biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae".Applied and Environmental Microbiology.71(12): 8241–8.Bibcode:2005ApEnM..71.8241L.doi:10.1128/AEM.71.12.8241-8248.2005.PMC1317445.PMID16332809.

- ^Meyer H, Bolarinwa A, Wolfram G, Linseisen J (2006)."Bioavailability of apigenin from apiin-rich parsley in humans".Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism.50(3): 167–72.doi:10.1159/000090736.PMID16407641.S2CID8223136.

- ^USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3 (2011)