Apple

| Apple | |

|---|---|

| |

| 'Cripps Pink' apples | |

| |

| Flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Malus |

| Species: | M. domestica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Malus domestica | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Anappleis a round, ediblefruitproduced by anapple tree(Malus spp.,among them thedomesticororchard apple;Malus domestica). Appletreesarecultivatedworldwide and are the most widely grown species in thegenusMalus.Thetreeoriginated inCentral Asia,where its wild ancestor,Malus sieversii,is still found. Apples have been grown for thousands of years in Eurasia and were introduced to North America byEuropean colonists.Apples havereligiousandmythologicalsignificance in many cultures, includingNorse,Greek,andEuropean Christiantradition.

Apples grown from seed tend to be very different from those of their parents, and the resultant fruit frequently lacks desired characteristics. For commercial purposes, including botanical evaluation, applecultivarsare propagated by clonalgraftingontorootstocks.Apple trees grown without rootstocks tend to be larger and much slower to fruit after planting. Rootstocks are used to control the speed of growth and the size of the resulting tree, allowing for easier harvesting.

There aremore than 7,500 cultivars of apples.Different cultivars are bred for various tastes and uses, includingcooking,eating raw, andciderorapple juiceproduction. Trees and fruit are prone tofungal,bacterial, and pest problems, which can be controlled by a number oforganicand non-organic means. In 2010, the fruit'sgenomewassequencedas part of research on disease control and selective breeding in apple production.

Etymology

The wordapple,whoseOld Englishancestor isæppel,is descended from theProto-Germanicnoun*aplaz,descended in turn fromProto-Indo-European*h₂ébōl.[3]

As late as the 17th century, the word also functioned as a generic term for all fruit, includingnuts.This can be compared to the 14th-centuryMiddle Englishexpressionappel of paradis,meaning abanana.[4]

Description

The apple is adeciduoustree, generally standing 2 to 4.5 metres (6 to 15 feet) tall in cultivation and up to 15 m (49 ft) in the wild, though more typically 2 to 10 m (6.5 to 33 ft).[5][1]When cultivated, the size, shape and branch density are determined byrootstockselection and trimming method.[5]Apple trees may naturally have a rounded to erect crown with a dense canopy of leaves.[6]The bark of the trunk is dark gray or gray-brown, but young branches are reddish or dark-brown with a smooth texture.[1][7]When young twigs are covered in very fine downy hairs and become hairless as they become older.[7]

The buds are egg shaped and dark red or purple in color and range in size from 3 to 5 millimeters, but usually less than 4 mm. Thebud scaleshave very hairy edges. When emerging from the buds the leaves areconvolute,that is their edges overlap each other.[1]The shape is ranges from simple ovals (elliptic) medium or wide in width, somewhat egg shaped with the wider portion toward their base (ovate) or even with sides that are more parallel to each other instead of curved (oblong) with a narrow pointed end.[7][1]The edges have broadly angled teeth, but do not have lobes. The top surface of the leaves areglabrescent,almost hairless, while the undersides are densely covered in fine hairs.[1]The leaves are attachedalternatelyby short leaf stems1-to-3.5 cm (1⁄2-to-1+1⁄2in) long.[6][1]

Blossomsare produced inspringsimultaneously with the budding of the leaves and are produced on spurs and some longshoots.[5]When the flower buds first begin to open thepetalsare rose-pink and fade to white or light pink when fully open with each flower3-to-4-centimeter (1-to-1+1⁄2-inch) in diameter.[1]The five petaled flowers are group in aninflorescenceconsisting of acymewith 4–6 flowers. The central flower of the inflorescence is called the "king bloom"; it opens first and can develop a larger fruit.[6]

Fruit

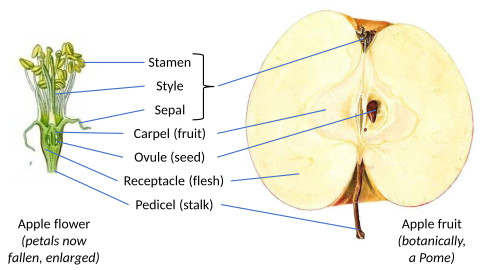

Thefruitis apomethat matures in latesummerorautumn.[1]The true fruits orcarpelsare the harder interior chambers inside the apple's core. There are usually five carpels inside an apple, but there may be as few as three. Each of the chambers contains one or two seeds.[8]The edible flesh is formed from the receptacle at the base of the flower.[9]

The seeds are egg- to pear-shaped and may be colored from light brown or tan to a very dark brown, often with red shades or even purplish-black. They may have a blunt or sharp point.[10]The five sepals remain attached and stand out from the surface of the apple.[1]

The size of the fruit varies widely between cultivars, but generally has a diameter between2.5 and 12 cm (1 and4+3⁄4in).[7]The shape is quite variable and may be nearly round, elongated, conical, or short and wide.[11]

The groundcolor of ripe apples is yellow, green, yellow-green or whitish yellow. The overcolor of ripe apples can be orange-red, pink-red, red, purple-red or brown-red. The overcolor amount can be 0–100%.[12]The skin may be wholly or partlyrusseted,making it rough and brown. The skin is covered in a protective layer ofepicuticular wax.[13]The skin may also be marked with scattered dots.[1]The flesh is generally pale yellowish-white, though it can be pink, yellow or green.[12]

- Apples can have any amount of overcolor, a darker tint over a pale groundcolor.

-

0% overcolor

-

100% overcolor

Chemistry

Important volatile compounds in apples that contribute to their scent and flavour includeacetaldehyde,ethyl acetate,1-butanal,ethanol,2-methylbutanal,3-methylbutanal,ethyl propionate,ethyl 2-methylpropionate,ethyl butyrate,ethyl 2-methyl butyrate,hexanal,1-butanol,3-methylbutyl acetate,2-methylbutyl acetate, 1-propyl butyrate,ethyl pentanoate,amyl acetate,2-methyl-1-butanol,trans-2-hexenal,ethyl hexanoate,hexanol.[14][15]

Taxonomy

The apple as a species has more than 100 alternative scientific names, orsynonyms.[16]In modern times,Malus pumilaandMalus domesticaare the two main names in use.M. pumilais the older name, butM. domesticahas become much more commonly used starting in the 21st century, especially in the western world. Two proposals were made to makeM. domesticaaconserved name:the earlier proposal was voted down by the Committee for Vascular Plants of theIAPTin 2014, but in April 2017 the Committee decided, with a narrow majority, that the newly popular name should be conserved.[17]The General Committee of the IAPT decided in June 2017 to approve this change, officially conservingM. domestica.[18]Nevertheless, some works published after 2017 still useM. pumilaas thecorrect name,under an alternate taxonomy.[2]

When first classified byLinnaeusin 1753, the pears, apples, and quinces were combined into one genus that he namedPyrusand he named the apple asPyrus malus.This was widely accepted, however the botanistPhilip Millerpublished an alternate classification inThe Gardeners Dictionarywith the apple species separated fromPyrusin 1754. He did not clearly indicate that byMalus pumilahe meant the domesticated apple. Nonetheless, it was used as such by many botanists. WhenMoritz Balthasar Borkhausenpublished his scientific description of the apple in 1803 it may have been a new combination ofP. malusvar.domestica,but this was not directly referenced by Borkhausen.[16]The earliest use of var.domesticafor the apple was byGeorg Adolf Suckowin 1786.[2]

Genome

Apples arediploid,with two sets ofchromosomesper cell (though triploid cultivars, with three sets, are not uncommon), have 17 chromosomes and an estimatedgenomesize of approximately 650 Mb. Several whole genome sequences have been completed and made available. The first one in 2010 was based on the diploid cultivar 'Golden Delicious'.[19]However, this first whole genome sequence contained several errors,[20]in part owing to the high degree ofheterozygosityin diploid apples which, in combination with an ancient genome duplication, complicated the assembly. Recently, double- and trihaploid individuals have been sequenced, yielding whole genome sequences of higher quality.[21][22]

The first whole genome assembly was estimated to contain around 57,000 genes,[19]though the more recent genome sequences support estimates between 42,000 and 44,700 protein-coding genes.[21][22]The availability of whole genome sequences has provided evidence that the wild ancestor of the cultivated apple most likely isMalus sieversii.Re-sequencing of multiple accessions has supported this, while also suggesting extensive introgression fromMalus sylvestrisfollowing domestication.[23]

Cultivation

History

Central Asiais generally considered the center of origin for apples due to the genetic variability in specimens there.[24]The wild ancestor ofMalus domesticawasMalus sieversii,found growing wild in themountains of Central Asiain southernKazakhstan,Kyrgyzstan,Tajikistan,andnorthwestern China.[5][25]Cultivation of the species, most likely beginning on the forested flanks of theTian Shanmountains, progressed over a long period of time and permitted secondaryintrogressionof genes from other species into the open-pollinated seeds. Significant exchange withMalus sylvestris,the crabapple, resulted in populations of apples being more related to crabapples than to the moremorphologicallysimilar progenitorMalus sieversii.In strains without recent admixture the contribution of the latter predominates.[26][27][28]

The apple is thought to have been domesticated 4,000–10,000 years ago in theTian Shanmountains, and then to have travelled along theSilk Roadto Europe, with hybridization and introgression of wild crabapples from Siberia (M. baccata), the Caucasus (M. orientalis), and Europe (M. sylvestris). Only theM. sieversiitrees growing on the western side of the Tian Shan mountains contributed genetically to the domesticated apple, not the isolated population on the eastern side.[23]

Chinese soft apples, such asM. asiaticaandM. prunifolia,have been cultivated as dessert apples for more than 2,000 years in China. These are thought to be hybrids betweenM. baccataandM. sieversiiin Kazakhstan.[23]

Among the traits selected for by human growers are size, fruit acidity, color, firmness, and soluble sugar. Unusually for domesticated fruits, the wildM. sieversiiorigin is only slightly smaller than the modern domesticated apple.[23]

At the Sammardenchia-Cueis site near Udine in Northeastern Italy, seeds from some form of apples have been found in material carbon dated to around 4000 BCE.[29]Genetic analysis has not yet been successfully used to determine whether such ancient apples were wildMalus sylvestrisorMalus domesticuscontainingMalus sieversiiancestry. It is hard to distinguish in the archeological record between foraged wild apples and apple plantations.[30]

There is indirect evidence of apple cultivation in the third millennium BCE in theMiddle East.There was substantial apple production in European classical antiquity, and grafting was certainly known then.[30]Grafting is an essential part of modern domesticated apple production, to be able to propagate the best cultivars; it is unclear when apple tree grafting was invented.[30]

The Roman writerPliny the Elderdescribes a method of storage for apples from his time in the 1st Century. He says they should be placed in a room with good air circulation from a north facing window on a bed of straw, chaff, or mats with windfalls kept separately.[31]Though methods like this will extend the availabity of reasonably fresh apples, without refrigeration their lifespan is limited. Even sturdy winter apple varieties will only keep well until December in cool climates.[32]For longer storage medieval Europeans strung up cored and peeled apples to dry, either whole or sliced into rings.[33]

Of the many Old World plants that the Spanish introduced toChiloé Archipelagoin the 16th century, apple trees became particularly well adapted.[34]Apples were introduced to North America by colonists in the 17th century,[5]and the first named apple cultivar was introduced inBostonby ReverendWilliam Blaxtonin 1640.[35]The only apples native to North America arecrab apples.[36]

Apple cultivars brought as seed from Europe were spread along Native American trade routes, as well as being cultivated on colonial farms. An 1845 United States apples nursery catalogue sold 350 of the "best" cultivars, showing the proliferation of new North American cultivars by the early 19th century.[36]In the 20th century, irrigation projects inEastern Washingtonbegan and allowed the development of the multibillion-dollar fruit industry, of which the apple is the leading product.[5]

Until the 20th century, farmers stored apples infrostproof cellarsduring the winter for their own use or for sale. Improved transportation of fresh apples by train and road replaced the necessity for storage.[37][38]Controlled atmospherefacilities are used to keep apples fresh year-round. Controlled atmosphere facilities use high humidity, low oxygen, and controlled carbon dioxide levels to maintain fruit freshness. They were first researched at Cambridge University in the 1920s and first used in the United States in the 1950s.[39]

Breeding

Many apples grow readily from seeds. However, apples must be propagated asexually to obtain cuttings with the characteristics of the parent. This is because seedling apples are "extreme heterozygotes".Rather than resembling their parents, seedlings are all different from each other and from their parents.[40]Triploidcultivars have an additional reproductive barrier in that three sets of chromosomes cannot be divided evenly during meiosis, yielding unequal segregation of the chromosomes (aneuploids). Even in the case when a triploid plant can produce a seed (apples are an example), it occurs infrequently, and seedlings rarely survive.[41]

Because apples are nottrue breederswhen planted as seeds, propagation usually involvesgraftingof cuttings. Therootstockused for the bottom of the graft can be selected to produce trees of a large variety of sizes, as well as changing the winter hardiness, insect and disease resistance, and soil preference of the resulting tree. Dwarf rootstocks can be used to produce very small trees (less than 3.0 m or 10 ft high at maturity), which bear fruit many years earlier in their life cycle than full size trees, and are easier to harvest.[42]

Dwarf rootstocks for apple trees can be traced as far back as 300 BCE, to the area ofPersiaandAsia Minor.Alexander the Greatsent samples of dwarf apple trees toAristotle'sLyceum.Dwarf rootstocks became common by the 15th century and later went through several cycles of popularity and decline throughout the world.[43]The majority of the rootstocks used to control size in apples were developed in England in the early 1900s. TheEast Malling Research Stationconducted extensive research into rootstocks, and their rootstocks are given an "M" prefix to designate their origin. Rootstocks marked with an "MM" prefix are Malling-series cultivars later crossed with trees of 'Northern Spy' inMerton, England.[44]

Most new apple cultivars originate as seedlings, which either arise by chance or are bred by deliberately crossing cultivars with promising characteristics.[45]The words "seedling", "pippin", and "kernel" in the name of an apple cultivar suggest that it originated as a seedling. Apples can also formbud sports(mutations on a single branch). Some bud sports turn out to be improved strains of the parent cultivar. Some differ sufficiently from the parent tree to be considered new cultivars.[46]

Apples have been acclimatized in Ecuador at very high altitudes, where they can often, with the needed factors, provide crops twice per year because of constant temperate conditions year-round.[47]

Pollination

Apples are self-incompatible; they mustcross-pollinateto develop fruit. During the flowering each season, apple growers often utilizepollinatorsto carry pollen.Honey beesare most commonly used.Orchard mason beesare also used as supplemental pollinators in commercial orchards.Bumblebeequeensare sometimes present in orchards, but not usually in sufficient number to be significant pollinators.[46][48]

Cultivars are sometimes classified by the day of peak bloom in the average 30-day blossom period, with pollinizers selected from cultivars within a 6-day overlap period. There are four to seven pollination groups in apples, depending on climate:

- Group A – Early flowering, 1 to 3 May in England ('Gravenstein', 'Red Astrachan')

- Group B – 4 to 7 May ('Idared', 'McIntosh')

- Group C – Mid-season flowering, 8 to 11 May ('Granny Smith', 'Cox's Orange Pippin')

- Group D – Mid/late season flowering, 12 to 15 May ('Golden Delicious', 'Calville blanc d'hiver')

- Group E – Late flowering, 16 to 18 May ('Braeburn', 'Reinette d'Orléans')

- Group F – 19 to 23 May ('Suntan')

- Group H – 24 to 28 May ('Court-Pendu Gris' – also called Court-Pendu plat)

One cultivar can be pollinated by a compatible cultivar from the same group or close (A with A, or A with B, but not A with C or D).[49]

Maturation and harvest

Cultivars vary in their yield and the ultimate size of the tree, even when grown on the same rootstock. Some cultivars, if left unpruned, grow very large—letting them bear more fruit, but making harvesting more difficult. Depending on tree density (number of trees planted per unit surface area), mature trees typically bear 40–200 kg (90–440 lb) of apples each year, though productivity can be close to zero in poor years. Apples are harvested using three-point ladders that are designed to fit amongst the branches. Trees grafted on dwarfing rootstocks bear about 10–80 kg (20–180 lb) of fruit per year.[46]

Some farms with apple orchards open them to the public so consumers can pick their own apples.[50]

Crops ripen at different times of the year according to the cultivar. Cultivar that yield their crop in the summer include 'Sweet Bough' and 'Duchess'; fall producers include 'Blenheim'; winter producers include 'King', 'Swayzie', and 'Tolman Sweet'.[36]

Storage

Commercially, apples can be stored for months incontrolled atmospherechambers. Apples are commonly stored in chambers with lowered concentrations ofoxygento reduce respiration and slow softening and other changes if the fruit is already fully ripe. The gasethyleneis used by plants as ahormonewhich promotes ripening, decreasing the time an apple can be stored. For storage longer than about six months the apples are picked earlier, before full ripeness, when ethylene production by the fruit is low. However, in many varieties this increases their sensitivity tocarbon dioxide,which also must be controlled.[51]

For home storage, most cultivars of apple can be held for approximately two weeks when kept at the coolest part of the refrigerator (i.e. below 5 °C).[52]Some varieties of apples (e.g. 'Granny Smith' and 'Fuji') have more than three times the storage life of others.[53]

Non-organic apples may be sprayed with a substance1-methylcyclopropeneblocking the apples' ethylene receptors, temporarily preventing them from ripening.[54]

Pests and diseases

Apple trees are susceptible tofungalandbacterialdiseases, and to damage by insect pests. Many commercial orchards pursue a program of chemical sprays to maintain high fruit quality, tree health, and high yields. These prohibit the use of synthetic pesticides, though some older pesticides are allowed.Organicmethods include, for instance, introducing its natural predator to reduce the population of a particular pest.

A wide range of pests and diseases can affect the plant. Three of the more common diseases or pests are mildew, aphids, and apple scab.

- Mildewis characterized by light grey powdery patches appearing on the leaves, shoots and flowers, normally in spring. The flowers turn a creamy yellow color and do not develop correctly. This can be treated similarly toBotrytis—eliminating the conditions that caused the disease and burning the infected plants are among recommended actions.[55]

- Aphidsare small insects withsucking mouthparts.Five species of aphids commonly attack apples: apple grain aphid, rosy apple aphid, apple aphid, spirea aphid, and the woolly apple aphid. The aphid species can be identified by color, time of year, and by differences in the cornicles (small paired projections from their rear).[56]Aphids feed on foliage using needle-like mouth parts to suck out plant juices. When present in high numbers, certain species reduce tree growth and vigor.[57]

- Apple scab:Apple scab causes leaves to develop olive-brown spots with a velvety texture that later turn brown and become cork-like in texture. The disease also affects the fruit, which also develops similar brown spots with velvety or cork-like textures. Apple scab is spread through fungus growing in old apple leaves on the ground and spreads during warm spring weather to infect the new year's growth.[58]

Among the most serious disease problems is a bacterial disease calledfireblight,and three fungal diseases:Gymnosporangiumrust,black spot,[59]andbitter rot.[60]Codling moths,and theapple maggotsof fruit flies, cause serious damage to apple fruits, making them unsaleable. Young apple trees are also prone to mammal pests like mice and deer, which feed on the soft bark of the trees, especially in winter.[58]The larvae of theapple clearwing moth (red-belted clearwing)burrow through the bark and into the phloem of apple trees, potentially causing significant damage.[61]

Cultivars

There are more than 7,500 knowncultivars(cultivated varieties) of apples.[62]Cultivars vary in theiryieldand the ultimate size of the tree, even when grown on the samerootstock.[63]Different cultivars are available fortemperateandsubtropicalclimates. The UK's National Fruit Collection, which is the responsibility of the Department of Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs, includes a collection of over 2,000 cultivars of apple tree in Kent.[64]TheUniversity of Reading,which is responsible for developing the UK national collection database, provides access to search the national collection. The University of Reading's work is part of the European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources of which there are 38 countries participating in the Malus/Pyrus work group.[65]

The UK's national fruit collection database contains much information on the characteristics and origin of many apples, including alternative names for what is essentially the same "genetic" apple cultivar. Most of these cultivars are bred for eating fresh (dessert apples), though some are cultivated specifically for cooking (cooking apples) or producingcider.Cider applesare typically too tart and astringent to eat fresh, but they give the beverage a rich flavor that dessert apples cannot.[66]

In the United States there are many apple breeding programs associated with universities.Cornell Universityhas had a program operating since 1880 inGeneva, New York.Among their recent well known apples is the 'SnapDragon' cultivar released in 2013. In the westWashington State Universitystarted a program to support their apple industry in 1994 and released the 'Cosmic Crisp' cultivar in 2017. The third most grown apple cultivar in the United States is the 'Honeycrisp', released by theUniversity of Minnesotaprogram in 1991.[67]Unusually for a popular cultivar, the 'Honeycrisp' is not directly related to another popular apple cultivar but instead to two unsuccessful cultivars.[68]In Europe there are also many breeding programs such as theJulius Kühn-Institut,the German federal research center for cultivated plants.[69]

Commercially popular apple cultivars are soft but crisp. Other desirable qualities in modern commercial apple breeding are a colorful skin, absence ofrusseting,ease of shipping, lengthy storage ability, high yields, disease resistance, common apple shape, and developed flavor.[63]Modern apples are generally sweeter than older cultivars, as popular tastes in apples have varied over time. Most North Americans and Europeans favor sweet, subacid apples, but tart apples have a strong minority following.[70]Extremely sweet apples with barely any acid flavor are popular in Asia,[70]especially theIndian subcontinent.[66]

Old cultivars are often oddly shaped, russeted, and grow in a variety of textures and colors. Some find them to have better flavor than modern cultivars, but they may have other problems that make them commercially unviable—low yield, disease susceptibility, poor tolerance for storage or transport, or just being the "wrong" size.[71]A few old cultivars are still produced on a large scale, but many have been preserved by home gardeners and farmers that sell directly to local markets. Many unusual and locally important cultivars with their own unique taste and appearance exist; apple conservation campaigns have sprung up around the world to preserve such local cultivars from extinction. In the United Kingdom, old cultivars such as 'Cox's Orange Pippin' and 'Egremont Russet' are still commercially important even though by modern standards they are low yielding and susceptible to disease.[5]

Production

| Apple production in 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Millions of tonnes |

47.6

| |

4.8

| |

4.4

| |

4.3

| |

2.6

| |

| World | 95.8

|

| Source:FAOSTATof the United Nations[72] | |

World production of apples in 2022 was 95 milliontonnes,with China producing 50% of the total (table).[72]Secondary producers were the United States and Turkey.[72]

Toxicity

Amygdalin

Apple seeds contain small amounts ofamygdalin,a sugar andcyanidecompound known as acyanogenic glycoside.Ingesting small amounts of apple seeds causes no ill effects, but consumption of extremely large doses can causeadverse reactions.It may take several hours before the poison takes effect, as cyanogenic glycosides must behydrolyzedbefore the cyanide ion is released.[73]The U.S.National Library of Medicine'sHazardous Substances Data Bankrecords no cases of amygdalin poisoning from consuming apple seeds.[74]

Allergy

One form of apple allergy, often found in northern Europe, is called birch-apple syndrome and is found in people who are also allergic tobirchpollen.[75]Allergic reactions are triggered by a protein in apples that is similar to birch pollen, and people affected by this protein can also develop allergies to other fruits, nuts, and vegetables. Reactions, which entailoral allergy syndrome(OAS), generally involve itching and inflammation of the mouth and throat,[75]but in rare cases can also include life-threateninganaphylaxis.[76]This reaction only occurs when raw fruit is consumed—the allergen is neutralized in the cooking process. The variety of apple, maturity and storage conditions can change the amount of allergen present in individual fruits. Long storage times can increase the amount of proteins that cause birch-apple syndrome.[75]

In other areas, such as the Mediterranean, some individuals have adverse reactions to apples because of their similarity to peaches.[75]This form of apple allergy also includes OAS, but often has more severe symptoms, such as vomiting, abdominal pain andurticaria,and can be life-threatening. Individuals with this form of allergy can also develop reactions to other fruits and nuts. Cooking does not break down the protein causing this particular reaction, so affected individuals cannot eat raw or cooked apples. Freshly harvested, over-ripe fruits tend to have the highest levels of the protein that causes this reaction.[75]

Breeding efforts have yet to produce ahypoallergenicfruit suitable for either of the two forms of apple allergy.[75]

Uses

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 218 kJ (52 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

13.81 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 10.39 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 2.4 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.17 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.26 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 85.56 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated usingUS recommendationsfor adults,[77]except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation fromthe National Academies.[78] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A raw apple is 86% water and 14%carbohydrates,with negligible content offatandprotein(table). A reference serving of a raw apple with skin weighing 100 grams provides 52caloriesand a moderate content ofdietary fiber.[79]Otherwise, there is low content ofmicronutrients,with theDaily Valuesof all falling below 10%.[80]

Culinary

Apples varieties can be grouped ascooking apples,eating apples,andcider apples,the last so astringent as to be "almost inedible".[81]Apples are consumed asjuice,raw in salads, baked inpies,cooked intosaucesandapple butter,or baked.[82]They are sometimes used as an ingredient in savory foods, such as sausage and stuffing.[83]

Several techniques are used to preserve apples and apple products. Traditional methods include drying and makingapple butter.[81]Juice and cider are produced commercially; cider is a significant industry in regions such as theWest of EnglandandNormandy.[81]

Atoffee apple(UK) orcaramel apple(US) is a confection made by coating an apple in hottoffeeorcaramelcandy respectively and allowing it to cool.[84][82]Apples and honeyare a ritualfood pairingeaten during the Jewish New Year ofRosh Hashanah.[85]

Apples are an important ingredient in many desserts, such aspies,crumbles,andcakes.When cooked, some apple cultivars easily form a puree known asapple sauce,which can be cooked down to form a preserve, apple butter. They are oftenbakedorstewed,and are cooked in some meat dishes.[81]

Apples aremilledorpressedto produceapple juice,which may be drunk unfiltered (calledapple ciderin North America), or filtered. Filtered juice is often concentrated and frozen, then reconstituted later and consumed. Apple juice can befermentedto makecider(called hard cider in North America),ciderkin,and vinegar. Throughdistillation,various alcoholic beverages can be produced, such asapplejack,Calvados,andapfelwein.[86]

Organic production

Organicapples are commonly produced in the United States.[87]Due to infestations by key insects and diseases, organic production is difficult in Europe.[88]The use of pesticides containing chemicals, such as sulfur, copper, microorganisms, viruses, clay powders, or plant extracts (pyrethrum,neem) has been approved by the EU Organic Standing Committee to improve organic yield and quality.[88]A light coating ofkaolin,which forms a physical barrier to some pests, also may help prevent apple sun scalding.[46]

Non-browning apples

Apple skins and seeds containpolyphenols.[89]These are oxidised by theenzymepolyphenol oxidase,which causesbrowningin sliced or bruised apples, bycatalyzingtheoxidationof phenolic compounds too-quinones,a browning factor.[90]Browning reduces apple taste, color, and food value.Arctic apples,a non-browning group of apples introduced to the United States market in 2019, have beengenetically modifiedto silence theexpressionof polyphenol oxidase, thereby delaying a browning effect and improving apple eating quality.[91][92]The USFood and Drug Administrationin 2015, andCanadian Food Inspection Agencyin 2017, determined that Arctic apples are as safe and nutritious as conventional apples.[93][94]

Other products

Apple seed oilis obtained bypressingapple seeds for manufacturingcosmetics.[95]

In culture

Germanic paganism

InNorse mythology,the goddessIðunnis portrayed in theProse Edda(written in the 13th century bySnorri Sturluson) as providing apples to thegodsthat give themeternal youthfulness.The English scholarH. R. Ellis Davidsonlinks apples to religious practices inGermanic paganism,from whichNorse paganismdeveloped. She points out that buckets of apples were found in theOseberg shipburial site in Norway, that fruit and nuts (Iðunn having been described as being transformed into a nut inSkáldskaparmál) have been found in the early graves of theGermanic peoplesin England and elsewhere on the continent of Europe, which may have had a symbolic meaning, and that nuts are still a recognized symbol offertilityin southwest England.[96]

Davidson notes a connection between apples and theVanir,a tribe of gods associated withfertilityin Norse mythology, citing an instance of eleven "golden apples" being given to woo the beautifulGerðrbySkírnir,who was acting as messenger for the major Vanir godFreyrin stanzas 19 and 20 ofSkírnismál.Davidson also notes a further connection between fertility and apples in Norse mythology in chapter 2 of theVölsunga saga:when the major goddessFriggsends KingReriran apple after he prays to Odin for a child, Frigg's messenger (in the guise of a crow) drops the apple in his lap as he sits atop amound.[96]Rerir's wife's consumption of the apple results in a six-year pregnancy and the birth (byCaesarean section) of their son—the heroVölsung.[97]

Further, Davidson points out the "strange" phrase "Apples ofHel"used in an 11th-century poem by theskaldThorbiorn Brúnarson. She states this may imply that the apple was thought of by Brúnarson as the food of the dead. Further, Davidson notes that the potentially Germanic goddessNehalenniais sometimes depicted with apples and that parallels exist in early Irish stories. Davidson asserts that while cultivation of the apple in Northern Europe extends back to at least the time of theRoman Empireand came to Europe from theNear East,the native varieties of apple trees growing in Northern Europe are small and bitter. Davidson concludes that in the figure of Iðunn "we must have a dim reflection of an old symbol: that of the guardian goddess of the life-giving fruit of the other world."[96]

Greek mythology

Apples appear in manyreligious traditions,often as a mystical orforbidden fruit.One of the problems identifying apples in religion,mythologyandfolktalesis that the word "apple" was used as a generic term for all (foreign) fruit, other than berries, including nuts, as late as the 17th century.[98]For instance, inGreek mythology,theGreek heroHeracles,as a part of hisTwelve Labours,was required to travel to the Garden of the Hesperides and pick the golden apples off theTree of Lifegrowing at its center.[99][100]

The Greek goddess of discord,Eris,became disgruntled after she was excluded from the wedding ofPeleusandThetis.[101]In retaliation, she tossed agolden appleinscribedΚαλλίστη(Kallistē,"For the most beautiful one" ), into the wedding party. Three goddesses claimed the apple:Hera,Athena,andAphrodite.ParisofTroywas appointed to select the recipient. After being bribed by both Hera and Athena, Aphrodite tempted him with the most beautiful woman in the world,HelenofSparta.He awarded the apple to Aphrodite, thus indirectly causing theTrojan War.[102]

The apple was thus considered, in ancient Greece, sacred to Aphrodite. To throw an apple at someone was to symbolically declare one's love; and similarly, to catch it was to symbolically show one's acceptance of that love. An epigram claiming authorship by Plato states:[103]

I throw the apple at you, and if you are willing to love me, take it and share your girlhood with me; but if your thoughts are what I pray they are not, even then take it, and consider how short-lived is beauty.

— Plato,Epigram VII

Atalanta,also of Greek mythology, raced all her suitors in an attempt to avoid marriage. She outran all butHippomenes(also known asMelanion,a name possibly derived frommelon,the Greek word for both "apple" and fruit in general),[100]who defeated her by cunning, not speed. Hippomenes knew that he could not win in a fair race, so he used three golden apples (gifts of Aphrodite, the goddess of love) to distract Atalanta. It took all three apples and all of his speed, but Hippomenes was finally successful, winning the race and Atalanta's hand.[99]

Celtic mythology

InCeltic mythology,theotherworldhas many names, includingEmain Ablach,"Emain of the Apple-trees". A version of this isAvaloninArthurian legend,or inWelshYnys Afallon,"Island of Apples".[104]

Christian art

Though theforbidden fruitofEdenin theBook of Genesisis not identified, popular Christian tradition has held that it was an apple thatEvecoaxedAdamto share with her.[105]The origin of the popular identification with a fruit unknown in the Middle East in biblical times is found in wordplay with theLatinwordsmālum(an apple) andmălum(an evil), each of which is normally writtenmalum.[106]The tree of the forbidden fruit is called "the tree of the knowledge of good and evil" in Genesis 2:17,[107]and the Latin for "good and evil" isbonum et malum.[108]

Renaissancepainters may also have been influenced by the story of thegolden applesin theGarden of Hesperides.As a result, in the story of Adam and Eve, the apple became a symbol for knowledge, immortality, temptation, the fall of man into sin, and sin itself. Thelarynxin the human throat has been called the "Adam's apple"because of a notion that it was caused by the forbidden fruit remaining in the throat of Adam. The apple as symbol of sexualseductionhas been used to imply human sexuality, possibly in an ironic vein.[105]

Proverb

Theproverb,"An apple a day keeps the doctor away",addressing the supposed health benefits of the fruit, has been traced to 19th-centuryWales,where the original phrase was "Eat an apple on going to bed, and you'll keep the doctor from earning his bread".[109]In the 19th century and early 20th, the phrase evolved to "an apple a day, no doctor to pay" and "an apple a day sends the doctor away"; the phrasing now commonly used was first recorded in 1922.[110]

See also

- Apple chip

- Applecrab,apple–crabapple hybrids for eating

- Cooking apple

- Johnny Appleseed

- List of apple cultivars

- List of apple dishes

References

- ^abcdefghijkDickson, Elizabeth E. (28 May 2021)."Malus domestica".Flora of North America.Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2024.Retrieved27 July2024.

- ^abc"Malus domestica(Suckow) Borkh ".Plants of the World Online.Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.Retrieved31 July2024.

- ^"Where the word 'apple' came from and why the apple was unlucky to be linked to the fall of man".South China Morning Post.6 July 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 28 June 2023.Retrieved28 June2023.

- ^"Origin and meaning of" apple "by Online Etymology Dictionary".Online Etymology Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2019.Retrieved22 November2019.

- ^abcdefgRieger, Mark."Apple -Malus domestica".HORT 3020: Intro Fruit Crops.University of Georgia.Archived fromthe originalon 21 January 2008.Retrieved22 January2008.

- ^abc"Apples -Malus domestica".North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox.North Carolina State University.Archivedfrom the original on 31 May 2024.Retrieved31 July2024.

- ^abcdHeil, Kenneth D.; O'Kane, Jr., Steve L.; Reeves, Linda Mary; Clifford, Arnold (2013).Flora of the Four Corners Region: Vascular Plants of the San Juan River Drainage, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah.St. Louis, Missouri:Missouri Botanical Garden.p. 909.Retrieved27 July2024.

- ^Juniper, Barrie E.;Mabberley, David J.(2006).The Story of the Apple.Portland, Oregon:Timber Press.p. 27.ISBN978-0-88192-784-9.Retrieved1 August2024.

- ^"Fruit glossary".Royal Horticultural Society.Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2024.Retrieved7 August2024.

- ^Burford, Tom(2013).Apples of North America: 192 Exceptional Varieties for Gardeners, Growers and Cooks(First ed.). Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. pp. 22, 50, 55, 122, 123, 137, 141, 147, 159, 245, 246.ISBN978-1-60469-249-5.

- ^"Shape".Western Agricultural Research Center.Montana State University.Archivedfrom the original on 23 April 2024.Retrieved30 July2024.

- ^abJanick, Jules; Cummins, James N.; Brown, Susan K.; Hemmat, Minou (1996)."Chapter 1: Apples"(PDF).In Jules Janick; James N. Moore (eds.).Fruit Breeding, Volume I: Tree and Tropical Fruits.John Wiley & Sons.pp. 9, 48.ISBN978-0-471-31014-3.Archived(PDF)from the original on 19 July 2013.

- ^"Natural Waxes on Fruits".Postharvest.tfrec.wsu.edu. 29 October 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 24 May 2013.Retrieved14 June2013.

- ^Flath, R. A.; Black, D. R.; Forrey, R. R.; McDonald, G. M.; Mon, T. R.; Teranishi, R. (1 August 1969). "Volatiles in Gravenstein Apple Essence Identified by GC-Mass Spectrometry".Journal of Chromatographic Science.7(8): 508.doi:10.1093/CHROMSCI/7.8.508.

- ^Flath, Robert A.; Black, Dale Robert.; Guadagni, Dante G.; McFadden, William H.; Schultz, Thomas H. (January 1967). "Identification and organoleptic evaluation of compounds in Delicious apple essence".Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.15(1): 29.doi:10.1021/jf60149a032.

- ^abQian, Guan-Ze; Liu, Lian-Fen; Tang, Geng-Guo (April 2010). "(1933) Proposal to conserve the nameMalus domesticaagainstM. pumila,M. communis,M. frutescens,andPyrus dioica( Rosaceae ) ".Taxon.59(2): 650–652.doi:10.1002/tax.592038.

- ^Applequist, Wendy L. (2017)."Report of the Nomenclature Committee for Vascular Plants: 69"(PDF).Taxon.66(2): 500–513.doi:10.12705/662.17.Archived(PDF)from the original on 7 May 2024.

- ^Wilson, Karen L. (June 2017)."Report of the General Committee: 18".Taxon.66(3): 742.doi:10.12705/663.15.

- ^abVelasco, Riccardo; Zharkikh, Andrey; Affourtit, Jason; Dhingra, Amit; Cestaro, Alessandro; et al. (2010)."The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus×domesticaBorkh.) ".Nature Genetics.42(10): 833–839.doi:10.1038/ng.654.PMID20802477.S2CID14854514.

- ^Di Pierro, Erica A.; Gianfranceschi, Luca; Di Guardo, Mario; Koehorst-Van Putten, Herma J.J.; Kruisselbrink, Johannes W.; et al. (2016)."A high-density, multi-parental SNP genetic map on apple validates a new mapping approach for outcrossing species".Horticulture Research.3(1): 16057.Bibcode:2016HorR....316057D.doi:10.1038/hortres.2016.57.PMC5120355.PMID27917289.

- ^abDaccord, Nicolas; Celton, Jean-Marc; Linsmith, Gareth; et al. (2017)."High-quality de novo assembly of the apple genome and methylome dynamics of early fruit development".Nature Genetics.49(7). Nature Communications: 1099–1106.doi:10.1038/ng.3886.hdl:10449/42064.PMID28581499.S2CID24690391.

- ^abZhang, Liyi; Hu, Jiang; Han, Xiaolei; Li, Jingjing; Gao, Yuan; et al. (2019)."A high-quality apple genome assembly reveals the association of a retrotransposon and red fruit colour".Nature Communications.10(1). Nature Genetics: 1494.Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1494Z.doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09518-x.PMC6445120.PMID30940818.

- ^abcdeDuan, Naibin; Bai, Yang; Sun, Honghe; Wang, Nan; Ma, Yumin; et al. (2017)."Genome re-sequencing reveals the history of apple and supports a two-stage model for fruit enlargement".Nature Communications.8(1): 249.Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..249D.doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00336-7.PMC5557836.PMID28811498.

- ^Richards, Christopher M.; Volk, Gayle M.; Reilley, Ann A.; Henk, Adam D.; Lockwood, Dale R.; et al. (2009). "Genetic diversity and population structure inMalus sieversii,a wild progenitor species of domesticated apple ".Tree Genetics & Genomes.5(2): 339–347.doi:10.1007/s11295-008-0190-9.S2CID19847067.

- ^Lauri, Pierre-éric; Maguylo, Karen; Trottier, Catherine (March 2006)."Architecture and size relations: an essay on the apple ( Malus × domestica, Rosaceae) tree".American Journal of Botany.93(3): 357–368.doi:10.3732/ajb.93.3.357.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2019.Retrieved27 July2024.

- ^Cornille, Amandine; Gladieux, Pierre; Smulders, Marinus J. M.; Roldán-Ruiz, Isabel; Laurens, François; et al. (2012). Mauricio, Rodney (ed.)."New Insight into the History of Domesticated Apple: Secondary Contribution of the European Wild Apple to the Genome of Cultivated Varieties".PLOS Genetics.8(5): e1002703.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002703.PMC3349737.PMID22589740.

- ^Kean, Sam (17 May 2012)."ScienceShot: The Secret History of the Domesticated Apple".Archivedfrom the original on 11 June 2016.

- ^Coart, E.; Van Glabeke, S.; De Loose, M.; Larsen, A.S.; Roldán-Ruiz, I. (2006). "Chloroplast diversity in the genusMalus:new insights into the relationship between the European wild apple (Malus sylvestris(L.) Mill.) and the domesticated apple (Malus domesticaBorkh.) ".Mol. Ecol.15(8): 2171–2182.Bibcode:2006MolEc..15.2171C.doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2006.02924.x.PMID16780433.S2CID31481730.

- ^Colledge, Sue; Conolly, James, eds. (16 June 2016).The Origins and Spread of Domestic Plants in Southwest Asia and Europe.Left Coast Press.ISBN9781598749885.

- ^abcSchlumbaum, Angela; van Glabeke, Sabine; Roldan-Ruiz, Isabel (January 2012). "Towards the onset of fruit tree growing north of the Alps: Ancient DNA from waterlogged apple (Malussp.) seed fragments ".Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger.194(1): 157–162.doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.03.004.PMID21501956.

- ^Plinius, Gaius Secundus(1855).The Natural History of Pliny.Vol. III. Translated byBostock, John;Riley, Henry T.London: Henry G. Bohn. p. 303.Retrieved3 August2024.

- ^Martin, Alice A. (1976).All about apples(First ed.). Boston, Massachusetts:Houghton Mifflin Company.pp. 64–65.ISBN978-0-395-20724-6.Retrieved3 August2024.

- ^Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004).Food in Medieval Times.Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 19–20.ISBN978-0-313-32147-4.

- ^Torrejón, Fernando; Cisternas, Marco; Araneda, Alberto (2004)."Efectos ambientales de la colonización española desde el río Maullín al archipiélago de Chiloé, sur de Chile"[Environmental effects of the spanish colonization from de Maullín river to the Chiloé archipelago, southern Chile].Revista Chilena de Historia Natural(in Spanish).77(4): 661–677.doi:10.4067/s0716-078x2004000400009.

- ^Smith, Archibald William (1963).A Gardener's Handbook of Plant Names: Their Meanings and Origins(First ed.). New York:Harper & Row.p. 40.Retrieved10 August2024.

- ^abcPoole, Mike (1980)."Heirloom Apples".In Lawrence, James (ed.).The Harrowsmith Reader Volume II.Camden East, Ontario:Camden House Publishing.p. 122.ISBN978-0-920656-11-2.Retrieved10 August2024.

- ^Van Valen, James M. (1900).History of Bergen County, New Jersey.New York: New Jersey Publishing and Engraving Company. pp. 33–34.Retrieved9 August2024.

- ^Brox, Jane(1999).Five Thousand Days Like This One.Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. pp. 150–151.ISBN978-0-8070-2106-4.Retrieved9 August2024.

- ^Cohen, Rachel D. (26 November 2018)."Thanks To Science, You Can Eat An Apple Every Day".The Salt.NPR.Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2024.Retrieved1 August2024.

- ^"The Heirloom Apple Orchard".The Jentsch Lab.Cornell University.Archivedfrom the original on 30 July 2024.Retrieved9 August2024.

- ^Ranney, Thomas G."Polyploidy: From Evolution to Landscape Plant Improvement".Proceedings of the 11th Metropolitan Tree Improvement Alliance (METRIA) Conference.11th Metropolitan Tree Improvement Alliance Conference held in Gresham, Oregon, August 23–24, 2000.METRIA (NCSU.edu).METRIA. Archived fromthe originalon 23 July 2010.Retrieved7 November2010.

- ^Lord, William G.; Ouellette, Amy (February 2010)."Dwarf Rootstocks for Apple Trees in the Home Garden"(PDF).University of New Hampshire.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 September 2013.Retrieved1 September2013.

- ^Fallahi, Esmaeil; Colt, W. Michael; Fallahi, Bahar; Chun, Ik-Jo (January 2002)."The Importance of Apple Rootstocks on Tree Growth, Yield, Fruit Quality, Leaf Nutrition, and Photosynthesis with an Emphasis on 'Fuji'".HortTechnology.12(1): 38–44.doi:10.21273/HORTTECH.12.1.38.Archived(PDF)from the original on 11 February 2014.Retrieved9 August2024.

- ^Parker, M.L. (September 1993)."Apple Rootstocks and Tree Spacing".North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service.Archived fromthe originalon 11 September 2013.Retrieved1 September2013.

- ^Ferree, David Curtis; Warrington, Ian J. (2003).Apples: Botany, Production, and Uses.New York: Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. pp. 33–35.ISBN978-0851995922.OCLC133167834.

- ^abcdPolomski, Bob; Reighard, Greg."Apple HGIC 1350".Home & Garden Information Center.Clemson University.Archived fromthe originalon 28 February 2008.Retrieved22 January2008.

- ^Barahona, M. (1992). "Adaptation of Apple Varieties in Ecuador".Acta Horticulturae(310): 135–142.doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.1992.310.17.

- ^Adamson, Nancy Lee (2011).An Assessment of Non-Apis Bees as Fruit and Vegetable Crop Pollinators in Southwest Virginia(PDF)(Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology thesis).Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.Archived(PDF)from the original on 20 November 2015.Retrieved15 October2015.

- ^Powell, L.E. (1986). "The Chilling Requirement in Apple and Its Role in Regulating Time of Flowering in Spring in Cold-Winter Climate".Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Growth Regulators in Fruit Production: Bologna-Rimini, 2 - 6 September 1985.Wageningen:International Society for Horticultural Science.pp. 129–140.doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.1986.179.10.ISBN978-90-6605-182-9.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^Romano, Andrea (10 September 2023)."20 Best Places to Go Apple Picking in the United States".Travel + Leisure.Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2024.Retrieved2 August2024.

- ^Graziano, Jack; Farcuh, Macarena (10 September 2021)."Controlled Atmosphere Storage of Apples".University of Maryland Extension.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023.Retrieved2 August2024.

- ^Yepsen, Roger (1994).Apples.New York: W.W. Norton & Co.ISBN978-0-393-03690-9.

- ^"Refrigerated storage of perishable foods".CSIRO.26 February 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 15 March 2015.Retrieved25 May2007.

- ^Karp, David (25 October 2006)."Puff the Magic Preservative: Lasting Crunch, but Less Scent".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2011.Retrieved26 July2017.

- ^Jackson, H.S. (1914)."Powdery Mildew".In Lowther, Granville; Worthington, William (eds.).The Encyclopedia of Practical Horticulture: A Reference System of Commercial Horticulture, Covering the Practical and Scientific Phases of Horticulture, with Special Reference to Fruits and Vegetables.Vol. I. North Yakima, Washington: The Encyclopedia of Horticulture Corporation. pp. 475–476.Retrieved1 August2024.

- ^Lowther, Granville; Worthington, William, eds. (1914).The Encyclopedia of Practical Horticulture: A Reference System of Commercial Horticulture, Covering the Practical and Scientific Phases of Horticulture, with Special Reference to Fruits and Vegetables.Vol. I. North Yakima, Washington: The Encyclopedia of Horticulture Corporation. pp. 45–51.Retrieved1 August2024.

- ^Coli, William M.; Los, Lorraine M., eds. (2003)."Insect Pests".2003-2004 New England Apple Pest Management Guide.University of Massachusetts Amherst.pp. 28–29. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008.Retrieved3 March2008.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^abAtthowe, Helen; Gilkeson, Linda A.; Kite, L. Patricia; Michalak, Patricia S.; Pleasant, Barbara; Reich, Lee; Scheider, Alfred F. (2009). Bradley, Fern Marshall; Ellis, Bardara W.; Martin, Deborah L. (eds.).The Organic Gardener's Handbook of Natural Pest and Disease Control.Rodale, Inc.pp. 32–34.ISBN978-1-60529-677-7.

- ^Coli, William M.; Berkett, Lorraine P.; Spitko, Robin, eds. (2003)."Other Apple Diseases".2003-2004 New England Apple Pest Management Guide.University of Massachusetts Amherst.pp. 19–27. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008.Retrieved3 March2008.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^Martin, Phillip L.; Krawczyk, Teresa; Khodadadi, Fatemeh; Aćimović, Srđan G.; Peter, Kari A. (2021)."Bitter Rot of Apple in the Mid-Atlantic United States: Causal Species and Evaluation of the Impacts of Regional Weather Patterns and Cultivar Susceptibility".Phytopathology.111(6): 966–981.doi:10.1094/PHYTO-09-20-0432-R.ISSN0031-949X.PMID33487025.S2CID231701083.

- ^Erler, Fedai (1 January 2010)."Efficacy of tree trunk coating materials in the control of the apple clearwing, Synanthedon myopaeformis".Journal of Insect Science.10(1): 63.doi:10.1673/031.010.6301.PMC3014806.PMID20672979.

- ^Elzebroek, A.T.G.; Wind, K. (2008).Guide to Cultivated Plants.Wallingford: Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. p. 27.ISBN978-1-84593-356-2.Archivedfrom the original on 20 October 2020.Retrieved6 October2020.

- ^ab"Apple –Malus domestica".Natural England.Archived fromthe originalon 12 May 2008.Retrieved22 January2008.

- ^"Home".National Fruit Collection.Archivedfrom the original on 15 June 2012.Retrieved2 December2012.

- ^"ECPGR Malus/Pyrus Working Group Members".Ecpgr.cgiar.org.22 July 2002. Archived fromthe originalon 26 August 2014.Retrieved25 August2014.

- ^abTarjan, Sue (Fall 2006)."Autumn Apple Musings"(PDF).News & Notes of the UCSC Farm & Garden, Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems. pp. 1–2. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 11 August 2007.Retrieved24 January2008.

- ^Beck, Kellen (17 October 2020)."How breeders bring out the best in new apples".Mashable.Archivedfrom the original on 31 July 2024.Retrieved31 July2024.

- ^Migicovsky, Zoë (22 August 2021)."How a few good apples spawned today's top varieties — and why breeders must branch out".The Conversation.Archivedfrom the original on 31 July 2024.Retrieved31 July2024.

- ^Peil, A.; Dunemann, F.; Richter, K.; Hoefer, M.; Király, I.; Flachowsky, H.; Hanke, M.-V. (2008)."Resistance Breeding in Apple at Dresden-Pillnitz".Ecofruit - 13th International Conference on Cultivation Technique and Phytopathological Problems in Organic Fruit-Growing: Proceedings to the Conference from 18thFebruary to 20th February 2008 at Weinsberg/Germany(in German): 220–225.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2021.Retrieved31 July2024.

- ^ab"World apple situation".Archived fromthe originalon 11 February 2008.Retrieved24 January2008.

- ^Weaver, Sue (June–July 2003)."Crops & Gardening – Apples of Antiquity".Hobby Farms Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on 19 February 2017.

- ^abc"Apple production in 2022; from pick lists: Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity".FAOSTAT, UNFood and Agriculture Organization,Statistics Division. 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2016.Retrieved18 June2024.

- ^Nelson, Lewis S.; Shih, Richard D.; Balick, Michael J. (2007).Handbook of poisonous and injurious plants.Springer.pp. 211–212.ISBN978-0-387-33817-0.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2013.Retrieved13 April2013.

- ^"Amygdalin".Toxnet, US Library of Medicine.Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2017.Retrieved20 April2017.

- ^abcdef"General Information – Apple".Informall. Archived fromthe originalon 23 July 2012.Retrieved17 October2011.

- ^Landau, Elizabeth,Oral allergy syndrome may explain mysterious reactions,8 April 2009,CNN Health,accessed 17 October 2011

- ^United States Food and Drug Administration(2024)."Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels".FDA.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2024.Retrieved28 March2024.

- ^National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.).Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium.The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).ISBN978-0-309-48834-1.PMID30844154.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2024.Retrieved21 June2024.

- ^"Nutrition Facts, Apples, raw, with skin [Includes USDA commodity food A343]. 100 gram amount".Nutritiondata,Conde Nastfrom USDA version SR-21. 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2012.Retrieved11 January2020.

- ^"How to understand and use the nutrition facts label".US Food and Drug Administration.11 March 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2022.Retrieved9 September2020.

- ^abcdDavidson, Alan(2014). "Apple". In Jaine, Tom (ed.).The Oxford Companion to Food(3rd ed.). Oxford:Oxford University Press.pp. 27–31.ISBN978-0-19-967733-7.

- ^abTraverso, Amy (2011).The Apple Lover's Cookbook(First ed.). New York:W.W. Norton & Company.pp. 16, 32, 35, 45, 92, 137, 262–263, 275.ISBN978-0-393-06599-2.

- ^Kellogg, Kristi (15 January 2015)."81 Best Apple Recipes: Dinners, Desserts, Salads, and More".Epicurious.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2020.Retrieved17 October2020.

- ^Davidson, Alan(2014). "Toffee apple". In Jaine, Tom (ed.).The Oxford Companion to Food(3rd ed.). Oxford:Oxford University Press.p. 824.ISBN978-0-19-967733-7.

- ^Shurpin, Yehuda."Why All the Symbolic Rosh Hashanah Foods?" בולבול "".Chabad.org.Archivedfrom the original on 21 March 2023.Retrieved21 March2023.

- ^Lim, T. K. (2012).Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants.Vol. 4, Fruits.Springer Publishing.ISBN978-940074053-2.

- ^"Organic apples".USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. February 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 24 February 2017.Retrieved23 February2017.

- ^ab"European Organic Apple Production Demonstrates the Value of Pesticides"(PDF).CropLife Foundation, Washington, DC. December 2011.Archived(PDF)from the original on 24 February 2017.Retrieved23 February2017.

- ^Ribeiro, Flávia A.P.; Gomes de Moura, Carolina F.; Aguiar, Odair; de Oliveira, Flavia; Spadari, Regina C.; Oliveira, Nara R.C.; Oshima, Celina T.F.; Ribeiro, Daniel A. (September 2014). "The chemopreventive activity of apple against carcinogenesis: antioxidant activity and cell cycle control".European Journal of Cancer Prevention(Review).23(5): 477–480.doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000005.PMID24366437.S2CID23026644.

- ^Nicolas, J. J.; Richard-Forget, F. C.; Goupy, P. M.; Amiot, M. J.; Aubert, S. Y. (1 January 1994). "Enzymatic browning reactions in apple and apple products".Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.34(2): 109–157.doi:10.1080/10408399409527653.PMID8011143.

- ^"PPO silencing".Okanagan Specialty Fruits. 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2021.Retrieved14 November2019.

- ^"United States: GM non-browning Arctic apple expands into foodservice".Fresh Fruit Portal. 13 August 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 27 June 2021.Retrieved14 November2019.

- ^"Okanagan Specialty Fruits: Biotechnology Consultation Agency Response Letter BNF 000132".U.S. Food and Drug Administration.20 March 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2017.Retrieved14 November2019.

- ^"Questions and answers: Arctic Apple".Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Government of Canada. 8 September 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2018.Retrieved14 November2019.

- ^Yu, Xiuzhu; Van De Voort, Frederick R.; Li, Zhixi; Yue, Tianli (2007). "Proximate Composition of the Apple Seed and Characterization of Its Oil".International Journal of Food Engineering.3(5).doi:10.2202/1556-3758.1283.S2CID98590230.

- ^abcDavidson, Hilda Roderick Ellis(1990).Gods and Myths of Northern Europe.London:Penguin Books.pp. 165–166.ISBN0-14-013627-4.

- ^Davidson, Hilda Ellis(1998).Roles of the Northern Goddess.London; New York:Routledge.pp. 146–147.ISBN0-415-13610-5.

- ^Sauer, Jonathan D. (1993).Historical Geography of Crop Plants: A Select Roster.Boca Raton:CRC Press.p. 109.ISBN978-0-8493-8901-6.

- ^abWasson, R. Gordon(1968).Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality.Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 128.ISBN978-0-15-683800-9.

- ^abRuck, Carl;Staples, Blaise Daniel(2001).The Apples of Apollo, Pagan and Christian Mysteries of the Eucharist.Durham:Carolina Academic Press.pp. 64–70.ISBN978-0-89089-924-3.

- ^Hyginus."92".Fabulae.Translated by Mary Grant.Archivedfrom the original on 9 February 2013.Retrieved7 December2017– via Theoi Project.

- ^Lucian."The Judgement of Paris".Dialogues of the Gods.Translated by H. W. Fowler; F. G. Fowler.Archivedfrom the original on 2 September 2017.Retrieved7 December2017– via Theoi Project.

- ^Edmonds, J.M. (1997)."Epigrams".In Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D.S. (eds.).Plato: Complete Works.Indianapolis:Hackett Publishing.p.1744.ISBN9780872203495.Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2021.Retrieved10 September2020.

- ^Flieger, Verlyn(2005). "The Otherworld".Interrupted Music.Kent, Ohio:Kent State University Press.pp. 122–123.ISBN978-0-87338-824-5.

- ^abMacrone, Michael (1998).Brush up your Bible!.New York:Gramercy Books.pp. 15–16, 340–341.ISBN978-0-517-20189-3.OCLC38270894.Retrieved31 July2024.

- ^Kissling, Paul J (2004).Genesis.Vol. 1. College Press. p. 193.ISBN978-0-89900875-2.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2021.Retrieved6 October2020.

- ^Genesis 2:17

- ^Hendel, Ronald (2012).The Book of Genesis: A Biography.Princeton University Press.p. 114.ISBN978-0-69114012-4.Archivedfrom the original on 29 January 2022.Retrieved6 October2020.

- ^Mieder, Wolfgang;Kingsbury, Stewart A.;Harder, Kelsie B.(1996).A Dictionary of American Proverbs(Paperback ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 23.ISBN978-0-19-511133-0.Retrieved23 August2024.

- ^Pollan, Michael(2001).The Botany of Desire: A Plant's-Eye View of the World(First ed.). New York:Random House.pp. 9, 22, 50.ISBN978-0-375-50129-6.

Further reading

- Bailey, L. H.(1922).The Apple-Tree.New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Browning, Frank(1998).Apples(First ed.). New York:North Point Press.ISBN978-0-86547-537-3.LCCN98027252.OCLC39235786.

- Juniper, Barrie E.;Mabberley, David J.(2006).The Story of the Apple(First ed.). Portland, Oregon:Timber Press.ISBN978-0-88192-784-9.LCCN2006011869.OCLC67383484.

- Sanders, Rosie (2010).The Apple Book(Second ed.). London:Frances Lincoln Limited.ISBN9780711231412.OCLC646397065.

External links

Media related toApplesat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toApplesat Wikimedia Commons