Arabic Alpha bet

| Arabic Alpha bet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 3rd century CE – present[1] |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Languages | Arabic |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Arab(160),Arabic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Arabic |

| |

| Arabic Alpha bet |

|---|

|

Arabic script |

TheArabic Alpha bet,[a]or theArabic abjad,is theArabic scriptas specifically codified for writing theArabiclanguage. It is written from right-to-left in acursivestyle, and includes 28 letters, of which most have contextual letterforms. The Arabic Alpha bet is considered anabjad,with onlyconsonantsrequired to be written; due to its optional use of diacritics to notate vowels, it is considered animpure abjad.[2]

Letters

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2024) |

The basic Arabic Alpha bet contains 28letters.Forms using the Arabic script to write other languages added and removed letters: for example ⟨ژ⟩ is often used to represent/ʒ/in adaptations of the Arabic script. UnlikeGreek-derived Alpha bets, Arabic has no distinctupper and lower caseletterforms.

Many letters look similar but are distinguished from one another by dots (ʾiʿjām) above or below their central part (rasm). These dots are an integral part of a letter, since they distinguish between letters that represent different sounds. For example, the Arabic lettersبb,تt,andثthhave the same basic shape, but with one dot added below, two dots added above, and three dots added above respectively. The letterنnalso has the same form in initial and medial forms, with one dot added above, though it is somewhat different in its isolated and final forms. Historically, they were often omitted, in a writing style calledrasm.

Both printed and written Arabic arecursive,with most letters within a word directly joined to adjacent letters.

Alphabetical order

[edit]There are two maincollating sequences(' Alpha betical orderings') for the Arabic Alpha bet:ʾabjadīy,andhijā’ī.

The originalʾabjadīorder derives from that used by thePhoenician Alpha bet,and is therefore reminiscent of the orderings of other Alpha bets, such as those inHebrewandGreek.With this ordering, letters are also used as numbers known asabjad numerals,possessing the same numerological codes as in Hebrewgematriaand Greekisopsephy.

Thehijā’īoralifbāʾīorder is used when sorting lists of words and names, such as in phonebooks, classroom lists, and dictionaries. The ordering groups letters by the graphical similarity of the glyphs' shapes.

Abjadi

[edit]Theʾabjadīorder is not a simple correspondence with the earlier north Semitic Alpha betic order, as it has a position corresponding to the Aramaic lettersamekס,which has no cognate letter in the Arabic Alpha bet historically.

The loss ofsameḵwas compensated for by:

- In theMashriqiabjad sequence, the lettershinשwas split into two Arabic letters,شshīnandﺱsīn,the latter of which took the place ofsameḵ.

- In theMaghrebiabjad sequence, the lettertsadeצwas split into two independent Arabic letters,ضḍadandصṣad,with the latter taking the place ofsameḵ.

The six other letters that do not correspond to any north Semitic letter are placed at the end.

| ا | ب | ج | د | ه | و | ز | ح | ط | ي | ك | ل | م | ن | س | ع | ف | ص | ق | ر | ش | ت | ث | خ | ذ | ض | ظ | غ | |

| ʾ | b | j | d | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | l | m | n | s | ʿ | f | ṣ | q | r | sh | t | th | kh | dh | ḍ | ẓ | gh | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | |

This is commonly vocalized as follows:

- ʾabjad hawwaz ḥuṭṭī kalaman saʿfaṣ qarashat thakhadh ḍaẓagh.

Another vocalization is:

- ʾabujadin hawazin ḥuṭiya kalman saʿfaṣ qurishat thakhudh ḍaẓugh[citation needed]

| ا | ب | ج | د | ه | و | ز | ح | ط | ي | ك | ل | م | ن | ص | ع | ف | ض | ق | ر | س | ت | ث | خ | ذ | ظ | غ | ش | |

| ʾ | b | j | d | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | l | m | n | ṣ | ʿ | f | ḍ | q | r | s | t | th | kh | dh | ẓ | gh | sh | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | |

| The colors indicate which letters have different positions from the previous table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This can be vocalized as:

- ʾabujadin hawazin ḥuṭiya kalman ṣaʿfaḍ qurisat thakhudh ẓaghush

Hijāʾī

[edit]

Modern dictionaries and other reference books do not use theabjadīorder to sort Alpha betically; instead, the newerhijāʾīorder is used wherein letters are partially grouped together by similarity of shape. Thehijāʾīorder is never used as numerals.

| ا | ب | ت | ث | ج | ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | س | ش | ص | ض | ط | ظ | ع | غ | ف | ق | ك | ل | م | ن | ه | و | ي | |

| ʾ | b | t | th | j | ḥ | kh | d | dh | r | z | s | sh | ṣ | ḍ | ṭ | ẓ | ʿ | gh | f | q | k | l | m | n | h | w | y | |

In thehijāʾīorder replaced recently[when?]by the Mashriqi order,[4][unreliable source?]though still used in many Quranic schools in Algeria,[citation needed]the sequence is:[3]

| ا | ب | ت | ث | ج | ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | ط | ظ | ك | ل | م | ن | ص | ض | ع | غ | ف | ق | س | ش | ه | و | ي | |

| ʾ | b | t | th | j | ḥ | kh | d | dh | r | z | ṭ | ẓ | k | l | m | n | ṣ | ḍ | ʿ | gh | f | q | s | sh | h | w | y | |

| The colors indicate which letters have different positions from the previous table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

InAbu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani's encyclopediaالإكليل من أخبار اليمن وأنساب حميرKitāb al-Iklīl min akhbār al-Yaman wa-ansāb Ḥimyar,the letter sequence is:[5]

| ا | ب | ت | ث | ج | ح | خ | د | ذ | ك | ل | م | و | ن | ص | ض | ع | غ | ط | ظ | ف | ق | ر | ز | ه | س | ش | ي | |

| ʾ | b | t | th | j | ḥ | kh | d | dh | k | l | m | w | n | ṣ | ḍ | ʿ | gh | ṭ | ẓ | f | q | r | z | h | s | sh | y | |

Letter forms

[edit]| Part ofa serieson |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

The Arabic Alpha bet is always cursive and letters vary in shape depending on their position within a word. Letters can exhibit up to four distinct forms corresponding to an initial, medial (middle), final, or isolated position (IMFI). While some letters show considerable variations, others remain almost identical across all four positions. Generally, letters in the same word are linked together on both sides by short horizontal lines, but six letters (و,ز,ر,ذ,د,ا) can only be linked to their preceding letter. In addition, some letter combinations are written asligatures(special shapes), notablylām-alifلا,[6]which is the only mandatory ligature (the unligated combinationلاis considered difficult to read).

Table of basic letters

[edit]| Maghrebian | Common | Closest English equivalent in pronunciation |

Letter name (Classical pronunciation;IPA) |

Letter name in Arabic script[b] |

Value in Literary Arabic (IPA) | Contextual forms | Isolated form | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʾAbjadī | Hijāʾī | ʾAbjadī | Hijāʾī | Final | Medial | Initial | |||||

| 1. | 1. | 1. | 1. | uh–oh /car,cat[c] | ʾalif([ʔalif]) | أَلِف | /ʔ/,/aː/[c] | ـا | ا | ||

| 2. | 2. | 2. | 2. | barn | bāʾ([baːʔ]) | بَاء | /b/ | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب |

| 22. | 3. | 22. | 3. | tick | tāʾ([taːʔ]) | تَاء | /t/ | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت |

| 23. | 4. | 23. | 4. | think | thāʾ([θaːʔ]) /ṯāʾ | ثَاء | /θ/ | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث |

| 3. | 5. | 3. | 5. | gem | jīm([d͡ʒiːm]) | جِيم | /d͡ʒ/[d] | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج |

| 8. | 6. | 8. | 6. | no equivalent (pharyngealh) |

ḥāʾ([ħaːʔ]) | حَاء | /ħ/ | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح |

| 24. | 7. | 24. | 7. | Scottishloch | khāʾ([xaːʔ]) /ḵāʾ | خَاء | /x/ | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ |

| 4. | 8. | 4. | 8. | dear | dāl([daːl]) | دَال | /d/ | ـد | د | ||

| 25. | 9. | 25. | 9. | that | dhāl([ðaːl]) /ḏāl | ذَال | /ð/ | ـذ | ذ | ||

| 20. | 10. | 20. | 10. | Scottishright | rāʾ([raːʔ]) | رَاء | /r/ | ـر | ر | ||

| 7. | 11. | 7. | 11. | zebra | zāy([zaːj]) | زَاي[e] | /z/ | ـز | ز | ||

| 21. | 24. | 15. | 12. | sin | sīn([siːn]) | سِين | /s/ | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س |

| 28. | 25. | 21. | 13. | shin | shīn([ʃiːn]) /šīn | شِين | /ʃ/ | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش |

| 15. | 18. | 18. | 14. | no equivalent (emphatics) |

ṣād([sˤaːd]) | صَاد | /sˤ/ | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص |

| 18. | 19. | 26. | 15. | no equivalent (emphaticd) |

ḍād([dˤaːd]) | ضَاد | /dˤ/ | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض |

| 9. | 12. | 9. | 16. | no equivalent (emphatict) |

ṭāʾ([tˤaːʔ]) | طَاء | /tˤ/ | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط |

| 26. | 13. | 27. | 17. | no equivalent (emphaticthe) |

ẓāʾ([ðˤaːʔ]) | ظَاء | /ðˤ/ | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ |

| 16. | 20. | 16. | 18. | no equivalent (similar toحḥāʾbut voiced) |

ʿayn([ʕajn]) | عَيْن | /ʕ/ | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع |

| 27. | 21. | 28. | 19. | no equivalent (Spanishabogado or Frenchrouge) |

ghayn([ɣajn]) /ḡayn | غَيْن | /ɣ/ | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ |

| 17. | 22. | 17. | 20. | far | fāʾ([faːʔ]) | فَاء | /f/ | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف[f] |

| 19. | 23. | 19. | 21. | no equivalent (MLEcut) |

qāf([qaːf]) | قَاف | /q/ | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق[f] |

| 11. | 14. | 11. | 22. | cap | kāf([kaːf]) | كَاف | /k/ | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | ك[f] |

| 12. | 15. | 12. | 23. | lamp | lām([laːm]) | لاَم | /l/ | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل |

| 13. | 16. | 13. | 24. | me | mīm([miːm]) | مِيم | /m/ | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م |

| 14. | 17. | 14. | 25. | nun | nūn([nuːn]) | نُون | /n/ | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن |

| 5. | 26. | 5. | 26. | hat | hāʾ([haːʔ]) | هَاء | /h/ | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ﻩ[g] |

| 6. | 27. | 6. | 27. | wow,pool | wāw([waːw]) | وَاو | /w/,/uː/[h] | ـو | و | ||

| 10. | 28. | 10. | 28. | yes,meet | yāʾ([jaːʔ]) | يَاء | /j/,/iː/[h] | ـي | ـيـ | يـ | ي[f] |

| 29. | 29. | 29. | 29. | uh–oh | hamzah | هَمْزة | /ʔ/ | ء[i]

(used in medial and final positions as an unlinked letter) | |||

Notes

- ^Arabic:الْأَبْجَدِيَّة الْعَرَبِيَّةal-ʾabjadiyyah l-ʿarabiyyah[alʔabd͡ʒaˈdijːa‿lʕaraˈbijːa]orالْحُرُوف الْعَرَبِيَّةal-ḥurūf al-ʿarabiyyah

- ^The Arabic letter names below are the standard and most universally used names, other names (e.g. letter names in Egypt) might be used instead.

- ^abAlifcan represent different phonemes; initially: a/i/u /a, i, u/ or sometimes silent in the definite article ال (a)l-. Medially and finally it represents a long vowel ā /aː/. It also part of the hamzah /ʔ/ forms, check#Hamzah forms

- ^The standard pronunciation ofج/d͡ʒ/ varies regionally, most prominently [d͡ʒ] in the Arabian Peninsula, parts of the Levant, Iraq, and northern Algeria, it is also considered as the predominant pronunciation of Literary Arabic when reciting the Quran and in Arabic studies outside the Arab world, [ʒ] in most of Northwest Africa and parts of the Levant (especially urban centers), while [ɡ] is the pronunciation only in lower Egypt, coastal Yemen, and coastal Oman, as well as [ɟ] in Sudan.

- ^زcan also be called ( "zāʾ" /زاء), ( "zayy" /زَيّ) or ( "zayn" /زين), but the standard is zāy.

- ^abcdSee the section onregional variationsin letter form.

- ^In certain contexts such as serial numbers and license plates the initial form is used to prevent confusion with the western number zero or Eastern Arabic Numeral for 5(٥)

- ^abThe letters ⟨و⟩ and ⟨ي⟩ are used to transcribe the vowels/oː/and/eː/respectively in loanwords and dialects, ⟨و⟩ is also used as a silent letter in some words like عمرو.

- ^(counted as a letter in the Arabic and plays an important role in Arabic spelling but not considered as one) denoting most irregular female nouns[citation needed]

- See the articleRomanization of Arabicfor details on various transliteration schemes. Arabic language speakers may usually not follow a standardized scheme when transcribing words or names. Some Arabic letters which do not have an equivalent in English (such as ط) are often spelled as numbers when Romanized. Also names are regularly transcribed as pronounced locally, not as pronounced inLiterary Arabic(if they were of Arabic origin).

- Regarding pronunciation, the phonemic values given are those of Modern Standard Arabic, which is taught in schools and universities. In practice, pronunciation may vary considerably from region to region. For more details concerning the pronunciation of Arabic, consult the articlesArabic phonologyandvarieties of Arabic.

- The names of the Arabic letters can be thought of as abstractions of an older version where they were meaningful words in theProto-Semiticlanguage. Names of Arabic letters may have quite different names popularly.

- Six letters (و ز ر ذ د ا) do not have a distinct medial form and have to be written with their final form without being connected to the next letter. Their initial form matches the isolated form. The following letter is written in its initial form, or isolated form if it is the final letter in the word.

- The letteraliforiginated in the Phoenician Alpha bet as a consonant-sign indicating a glottal stop. Today it has lost its function as a consonant, and, together withya’andwāw,is amater lectionis,a consonant sign standing in for a long vowel (see below), or as support for certain diacritics (maddahandhamzah).

- Arabic currently uses apunctuation markcalled thehamzah(ء) to denote theglottal stop[ʔ],written alone or with a carrier:

- alone:ء

- with a carrier:إ أ(above or under analif),ؤ(above awāw),ئ(above a dotlessyā’oryā’ hamzah).

- In academic work, the hamzah is transliterated with themodifier letter right half ring(ʾ), while themodifier letter left half ring(ʿ) transliterates the letter‘ayn(ع), which represents a different sound, not found in English.

- The hamzah has a single form, since it is never linked to a preceding or following letter. However, it is sometimes combined with awāw,yā’,oralif,and in that case the carrier behaves like an ordinarywāw,yā’,oralif,check the table below:

Hamzah forms

[edit]| Name | Contextual forms | Isolated | Position occurrence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | Medial | Initial | |||

| Hamzah ʿalā al-ʾalif(هَمْزَة عَلَى الأَلِفْ) | ـأ | أ | Initial / Medial / Final positions | ||

| Hamzah taḥt al-ʾalif(هَمْزَة تَحْت الأَلِفْ) | - | إ | Initial position only | ||

| Hamzah ʿalā as-saṭr(هَمْزَة عَلَى السَّطْر) | ء | - | ء | Medial / Final only | |

| Hamzah ʿalā al-wāw(هَمْزَة عَلَى الوَاو) | ـؤ | - | ؤ | Medial / Final only | |

| Hamzah ʿalā nabra(هَمْزَة عَلَى نَبْرَة) (medial) Hamzah ʿalā al-yāʾ(هَمْزَة عَلَى اليَاء) (final) |

ـئ | ـئـ | - | ئ | Medial / Final only |

| Hamzat al-madd(هَمْزَةْ المد) | - | ـآ | آ | Initial / Medial only | |

For the writing rule of each form, checkHamza.

Modified letters

[edit]The following are not individual letters, but rather different contextual variants of some of the Arabic letters.

| Name | Contextual forms | Isolated | Translit. | Phonemic Value (IPA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | Medial | Initial | ||||

| tāʾ marbūṭah

(تَاءْ مَرْبُوطَة) |

ـة | (only final) | ة | hor t/ẗ |

(aka "correlated tā'")

used in final position only and for denoting the femininenoun/wordor to make thenoun/wordfeminine; however, in rareirregular noun/wordcases, it appears to denote the "masculine"; singular nouns:/a/, plural nouns:āt(a preceding letter followed by afatḥah alif+tāʾ=ـَات) | |

| ʾalif maqṣūrah(أَلِفْ مَقْصُورَة) | ـى | (only final) | ى | āor y/ỳ |

Two uses: 1. The letter calledأَلِفْ مَقْصُورَةalif maqṣūrahorْأَلِف لَيِّنَةalif layyinah(as opposed toأَلِف مَمْدُودَةalif mamdūdaا), pronounced/aː/in Modern Standard Arabic. It is used only at the end of words in some special cases to denote the neuter/non-feminine aspect of the word (mainly verbs), wheretā’ marbūṭahcannot be used. [citation needed] 2. A way of writing the letterيyāʾwithout its dots at the end of words, either traditionally or in contemporary use in Egypt and Sudan. | |

| ʾalif al-waṣl

(أَلِفُ ٱلْوَصْلِ) |

(only initial) | ٱorا | silent

(checkWasla) |

| ||

Gemination

[edit]Geminationis the doubling of a consonant. Instead of writing the letter twice, Arabic places aW-shaped sign calledshaddah,above it. Note that if a vowel occurs between the two consonants the letter will simply be written twice. The diacritic only appears where the consonant at the end of one syllable is identical to the initial consonant of the following syllable. (The generic term for such diacritical signs isḥarakāt),e. g.,درسdarasa(with full diacritics:دَرَسَ) is a Form I verb meaningto study,whereasدرّسdarrasa(with full diacritics:دَرَّسَ) is the corresponding Form II verb, with the middlerconsonant doubled, meaningto teach.

| General Unicode | Name | Name in Arabic script | Transliteration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0651 |

ــّـ |

shaddah | شَدَّة | (consonant doubled/geminated) |

Nunation

[edit]Nunation (Arabic:تنوينtanwīn) is the addition of a final-nto anounoradjective.The vowel before it indicatesgrammatical case.In written Arabic nunation is indicated by doubling the vowel diacritic at the end of the word.

Ligatures

[edit]

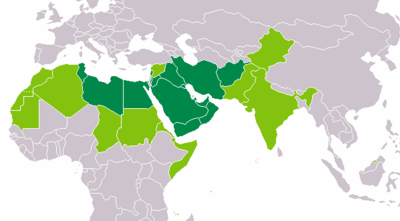

1.alif

2.hamzat waṣl(ْهَمْزَة وَصْل)

3.lām

4. lām

5.shadda(شَدَّة)

6.dagger alif(أَلِفْ خَنْجَریَّة)

7.hāʾ

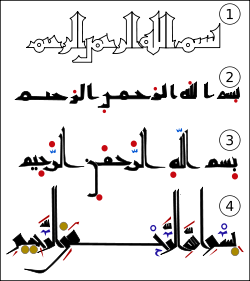

The use ofligaturein Arabicis common. There is one compulsory ligature, that forlāmل +alifا, which exists in two forms. All other ligatures, of which there are many,[7]are optional.

| Contextual forms | Name | Trans. | Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | Medial | Initial | Isolated | |||

| ﻼ | ﻻ | lām + alif | laa | /laː/ | ||

| ﲓ | ﳰ | ﳝ[8] | ﱘ | yāʾ + mīm | īm | /iːm/ |

| ﲅ | ﳭ | ﳌ | ﱂ | lam + mīm | lm | /lm/ |

A more complex ligature that combines as many as seven distinct components is commonly used to represent the wordAllāh.

The only ligature within the primary range ofArabic script in Unicode(U+06xx) islām+alif.This is the only one compulsory for fonts and word-processing. Other ranges are for compatibility to older standards and contain other ligatures, which are optional.

- lām+alif

- لا

Note:Unicodealso has in its Presentation Form B FExx range a code for this ligature. If your browser and font are configured correctly for Arabic, the ligature displayed above should be identical to this one,U+FEFBARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF ISOLATED FORM:

- ﻻ

U+0640ARABIC TATWEEL +lām+alif- ـلا

Note:Unicodealso has in its Presentation Form B U+FExx range a code for this ligature. If your browser and font are configured correctly for Arabic, the ligature displayed above should be identical to this one:

U+FEFCARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF FINAL FORM- ﻼ

Another ligature in theUnicodePresentation Form A range U+FB50 to U+FDxx is the special code for glyph for the ligatureAllāh( "God" ),U+FDF2ARABIC LIGATURE ALLAH ISOLATED FORM:

- ﷲ

This is a work-around for the shortcomings of most text processors, which are incapable of displaying the correctvowel marksfor the wordAllāhin theQuran.Because Arabic script is used to write other texts rather than Quran only, renderinglām+lām+hā’as the previous ligature is considered faulty.

This simplified style is often preferred for clarity, especially in non-Arabic languages, but may not be considered appropriate in situations where a more elaborate style of calligraphy is preferred. –SIL International[9]

If one of a number of the fonts (Noto Naskh Arabic, mry_KacstQurn, KacstOne, Nadeem, DejaVu Sans, Harmattan, Scheherazade, Lateef, Iranian Sans, Baghdad, DecoType Naskh) is installed on a computer (Iranian Sans is supported by Wikimedia web-fonts), the word will appear without diacritics.

- lām+lām+hā’= LILLĀH (meaning"to Allāh [only to God]" )

- للهorلله

- alif+lām+lām+hā’= ALLĀH (the Arabic word for "god" )

- اللهorالله

- alif+lām+lām+

U+0651ARABIC SHADDA +U+0670ARABIC LETTER SUPERSCRIPT ALEF +hā’- اللّٰه(DejaVu SansandKacstOnedon't show the added superscript Alef)

An attempt to show them on the faulty fonts without automatically adding the gemination mark and the superscript alif, although may not display as desired on all browsers, is by adding theU+200d(Zero width joiner) after the first or secondlām

- (alif+)lām+lām+

U+200dZERO WIDTH JOINER +hā’- اللهلله

Vowels

[edit]Users of Arabic usually writelong vowelsbut omit short ones, so readers must utilize their knowledge of the language in order to supply the missing vowels. However, in the education system and particularly in classes on Arabic grammar these vowels are used since they are crucial to the grammar. An Arabic sentence can have a completely different meaning by a subtle change of the vowels. This is why in an important text such as theQur’ānthe three basic vowel signs are mandated, like the Arabic diacritics and other types of marks, like thecantillation signs.

Short vowels

[edit]In the Arabic handwriting of everyday use, in general publications, and on street signs, short vowels are typically not written. On the other hand, copies of theQur’āncannot be endorsed by the religious institutes that review them unless the diacritics are included. Children's books, elementary school texts, and Arabic-language grammars in general will include diacritics to some degree. These are known as "vocalized"texts.

Short vowels may be written with diacritics placed above or below the consonant that precedes them in the syllable, calledḥarakāt.All Arabic vowels, long and short, follow a consonant; in Arabic, words like "Ali" or "alif", for example, start with a consonant:‘Aliyy,alif.

| Short vowels (fullyvocalizedtext) |

Code | Name | Name in Arabic script | Trans. | Phonemic Value | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ــَـ | 064E | fat·ḥah | فَتْحَة | a | /a/ | Ranges from[æ],[a],[ä],[ɑ],[ɐ],to[e],depending on the native dialect, position, and stress. |

| ــُـ | 064F | ḍammah | ضَمَّة | u | /u/ | Ranges from[ʊ],[o],to[u],depending on the native dialect, position, and stress. Approximated to English "OO" (as "boot "but shorter) |

|

ــِـ |

0650 | kasrah | كَسْرَة | i | /i/ | Ranges from[ɪ],[e],to[i],depending on the native dialect, position, and stress. Approximated to English "I" (as in "pick ") |

Long vowels

[edit]In the fully vocalized Arabic text found in texts such as the Quran, a longāfollowing a consonant other than ahamzahis written with a shortasign (fatḥah) on the consonant plus anʾalifafter it; longīis written as a sign for shorti(kasrah) plus ayāʾ;and longūas a sign for shortu(ḍammah) plus awāw.Briefly,ᵃa=ā;ⁱy=ī;andᵘw=ū.Longāfollowing ahamzahmay be represented by anʾalif maddahor by a freehamzahfollowed by anʾalif(two consecutiveʾalifs are never allowed in Arabic).

The table below shows vowels placed above or below a dotted circle replacing a primary consonant letter or ashaddahsign. For clarity in the table, the primary letters on the left used to mark these long vowels are shown only in their isolated form. Most consonants do connect to the left withʾalif,wāwandyāʾwritten then with their medial or final form. Additionally, the letteryāʾin the last row may connect to the letter on its left, and then will use a medial or initial form. Use the table of primary letters to look at their actual glyph and joining types.

| Unicode | Letter with diacritic | Name | Trans. | Variants | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 064E 0627 | ـَـا | fatḥah ʾalif | ā | aa | /aː/ |

| 064E 0649 | ـَـى | fatḥah ʾalif maqṣūrah | ā | aa | |

| 064F 0648 | ـُـو | ḍammah wāw | ū | uw/ ou | /uː/ |

| 0650 064A | ـِـي | kasrah yāʾ | ī | iy | /iː/ |

| 0650 0649 | ـِـى[a] | kasrah yāʾ | ī | iy | /iː/ |

In unvocalized text (one in which the short vowels are not marked), the long vowels are represented by the vowel in question:ʾalif ṭawīlah/maqṣūrah,wāw,oryāʾ.Long vowels written in the middle of a word of unvocalized text are treated like consonants with asukūn(see below) in a text that has full diacritics. Here also, the table shows long vowel letters only in isolated form for clarity.

Combinationsواandياare always pronouncedwāandyāʾrespectively. The exception is the suffixـوا۟in verb endings whereʾalifis silent, resulting inūoraw.

| Long vowels (unvocalized text) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0627 ا |

(impliedfatḥah)ʾalif | ā | /aː/ |

| 0649 ى |

(impliedfatḥah)ʾalif maqṣūrah | ā/y | |

| 0648 و |

(impliedḍammah)wāw | ū | /uː/ |

| 064A ي |

(impliedkasrah)yāʾ | ī | /iː/ |

In addition, when transliterating names and loanwords, Arabic language speakers write out most or all the vowels as long (āwithاʾalif,ēandīwithيyaʾ,andōandūwithوwāw), meaning it approaches a true Alpha bet.

Diphthongs

[edit]Thediphthongs/aj/and/aw/are represented in vocalized text as follows:

| Diphthongs (fullyvocalizedtext) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 064A 064E ـَـي |

fatḥah yāʾ | ay | /aj/ |

| 0648 064E ـَـو |

fatḥah vāv/ wāw | aw | /aw/ |

Vowel omission

[edit]An Arabicsyllablecan be open (ending with a vowel) or closed (ending with a consonant):

- open: CV [consonant-vowel] (long or short vowel)

- closed: CVC (short vowel only)

A normal text is composed only of a series of consonants plus vowel-lengthening letters; thus, the wordqalb,"heart", is writtenqlb,and the wordqalaba"he turned around", is also writtenqlb.

To writeqalabawithout this ambiguity, we could indicate that thelis followed by a shortaby writing afatḥahabove it.

To writeqalb,we would instead indicate that thelis followed by no vowel by marking it with adiacriticcalledsukūn(ْ), like this:قلْب.

This is one step down from full vocalization, where the vowel after theqwould also be indicated by afatḥah:قَلْب.

TheQurʾānis traditionally written in full vocalization.

The longisound in some editions of theQur’ānis written with akasrahfollowed by a diacritic-lessy,and longuby aḍammahfollowed by a barew.In others, theseyandwcarry asukūn.Outside of theQur’ān,the latter convention is extremely rare, to the point thatywithsukūnwill be unambiguously read as thediphthong/aj/,andwwithsukūnwill be read/aw/.

For example, the lettersm-y-lcan be read like Englishmeelormail,or (theoretically) also likemayyalormayil.But if asukūnis added on theythen themcannot have asukūn(because two letters in a row cannot besukūnated), cannot have aḍammah(because there is never anuysound in Arabic unless there is another vowel after they), and cannot have akasrah(becausekasrahbeforesukūnatedyis never found outside theQur’ān), so itmusthave afatḥahand the only possible pronunciation is/majl/(meaning mile, or even e-mail). By the same token, m-y-t with asukūnover theycan bemaytbut notmayyitormeet,and m-w-t with asukūnon thewcan only bemawt,notmoot(iwis impossible when thewcloses the syllable).

Vowel marks are always written as if thei‘rābvowels were in fact pronounced, even when they must be skipped in actual pronunciation. So, when writing the nameAḥmad,it is optional to place asukūnon theḥ,but asukūnis forbidden on thed,because it would carry aḍammahif any other word followed, as inAḥmadu zawjī"Ahmad is my husband".

Another example: the sentence that in correct literary Arabic must be pronouncedAḥmadu zawjun shirrīr"Ahmad is a wicked husband", is usually pronounced (due to influence from vernacular Arabic varieties) asAḥmad zawj shirrīr.Yet, for the purposes of Arabic grammar and orthography, is treated as if it were not mispronounced and as if yet another word followed it, i.e., if adding any vowel marks, they must be added as if the pronunciation wereAḥmadu zawjun sharrīrunwith atanwīn'un' at the end. So, it is correct to add anuntanwīnsign on the finalr,but actually pronouncing it would be a hypercorrection. Also, it is never correct to write asukūnon thatr,even though in actual pronunciation it is (and in correct Arabic MUST be)sukūned.

Of course, if the correcti‘rābis asukūn,it may be optionally written.

| General Unicode | Name | Name in Arabic script | Translit. | Phonemic Value (IPA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0652 | ــْـ | sukūn | سُكُون | (no vowel with this consonant letter or diphthong with this long vowel letter) |

∅ |

| 0670 | ــٰـ | alif khanjariyyah [dagger ’alif – smaller ’alif written above consonant] | أَلِف خَنْجَرِيَّة | ā | /aː/ |

ٰٰ Thesukūnis also used for transliterating words into the Arabic script. The English name "Mark" is writtenمارك,for example, might be written with asukūnabove theرto signify that there is no vowel sound between that letter and theك.

Additional letters

[edit]Non-native letters to Standard Arabic

[edit]Some modified letters are used to represent non-native sounds of Modern Standard Arabic. These letters are used in transliterated names, loanwords and dialectal words.

| Letter | Phoneme | Note |

|---|---|---|

| پ | /p/ | Sometimes used when transliterating foreign names and loanwords instead ofbā’ب |

| ڤ | /v/ | Sometimes used when transliterating foreign names and loanwords instead offā’ف.[10]Not to be confused withڨ. |

| ڥ | Used in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. | |

| چ | /t͡ʃ/1 | Used in Gulf andIraqiArabic dialects (e.g.چلب[t͡ʃəlb]"dog" instead of Standard Arabicكلب[kalb]). The sequenceتشtāʼ-shīnis usually preferred in most of the Arab world (e.g.تشاد[t͡ʃaːd]"Chad"). |

| /ʒ~d͡ʒ/ | Used in Egypt where standardج is mostly pronounced/ɡ/,(e.g.چيبة orجيبة[ʒiː.ba]"skirt" ). | |

| /ɡ/ | Used in Israel, for example on road signs. | |

| گ | Used in Gulf and Iraqi Arabic dialects | |

| ڨ | Used in Tunisia and in Algeria for loanwords and for the dialectal pronunciation ofqāfق in some words. Not to be confused withڤ. | |

| ڭ | Used in Morocco. |

- /t͡ʃ/is considered a native phoneme/allophone in some dialects, e.g.Gulf Arabicand Iraqi dialects.

The phoneme/g/is considered native in most Arabic dialects, below are the dominant letter representations of the phoneme in native words or nativized loanwords across each country or region:

| Morocco1 | Iraq2 | Gulf3 | Algeria4 | Tunisia4 | Libya | Mauritania | Saudi Arabia | South Levant | Sudan | Egypt5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ڭ/ك/گ/ق/ج | گ/ك/ق | گ/ق | ڨ/ق | ق | ج | |||||

- In Morocco/g/can be written usingڭorكorگin official city names; the city ofAgadir[ʔaɡaːdiːr]is writtenأڭاديرorأكادير.An exception to this rule are the letterجwhich is mostly pronounced/ʒ/but sometimes pronounced/g/in some words as inجلس[gləs]"He sat", and the letterقwhich can be pronounced/g/instead of/q/in some words depending on the accent (e.g. inCasablanca) as inبقرة"cow" pronounced[bagra]or[baqra].

- In Iraq/g/can be written usingكorگinstead ofقeven in native Arabic words;كالorگال[gaːl]"He says" instead Standard Arabicقال.

- In theGulf region(other than Saudi Arabia and Oman)/g/is mostly written with the nativeقbut sometimesگis used instead depending on the writer.

- In Algeria and Tunisia/g/can be written usingڨinstead ofقin official city names; the city ofGuelma[ɡelmæ]is writtenڨالمةorقالمةandGafsa[gafsˤa]is writtenڨفصةorقفصة.

- In Egypt,جspells/g/in all cases,[11]which is the dominant pronunciation even though some regions in Egypt pronounce theجas /ʒ~d͡ʒ/, the same applies to Oman, and coastal Yemen, as in the city ofGiza[elˈgiːzæ]is writtenالجيزة.

The same rules can apply to loanwords based on each country but sometimes the/ɡ/is spelled differently in non-native words as in "golf" can be writtenجولف,غولف,قولف,orكولف/ɡoːlf/.In many dialects throughout theLevantthe phoneme/g/is not considered native especially in the urban centers, but still most speakers are able to pronounce it.

Used in languages other than Arabic

[edit]Regional variations

[edit]Some letters take a traditionally different form in specific regions:

| Letter | Explanation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial | |

| ڛ | ـڛ | ـڛـ | ڛـ | A traditional form to denotate thesīnسletter, used in areas influenced byPersian scriptand formerOttoman script,although rarely. Also used in olderPashto script.[12] |

| ڢ | ـڢ | ـڢـ | ڢـ | A traditionalMaghrebi variantoffā’ف. |

| ڧ/ٯ | ـڧ/ـٯ | ـڧـ/ـٯـ | ڧـ/ٯـ | A traditionalMaghrebi variantofqāfق.Generally dotless in isolated and final positions and dotted in the initial and medial forms. |

| ک | ـک | ـکـ | کـ | An alternative version ofkāfكused especially inMaghrebiunder the influence of theOttoman scriptor inGulfscript under the influence of thePersian script. |

| ی | ـی | ـیـ | یـ | The traditional style to write or print the letter, and remains so in theNile Valleyregion (Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan... etc.) and sometimes Maghreb;yā’يis dotless in the isolated and final position. Visually identical toalif maqṣūrahى;resembling the Perso-Arabic letterیـ ـیـ ـییwhich was also used inOttoman Turkish. |

Numerals

[edit]| Western (Maghreb, Europe) |

Central (Mideast) |

Eastern | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persian | Urdu | ||

| 0 | ٠ | ۰ | ۰ |

| 1 | ١ | ۱ | ۱ |

| 2 | ٢ | ۲ | ۲ |

| 3 | ٣ | ۳ | ۳ |

| 4 | ٤ | ۴ | ۴ |

| 5 | ٥ | ۵ | ۵ |

| 6 | ٦ | ۶ | ۶ |

| 7 | ٧ | ۷ | ۷ |

| 8 | ٨ | ۸ | ۸ |

| 9 | ٩ | ۹ | ۹ |

| 10 | ١٠ | ۱۰ | ۱۰ |

There are two main kinds of numerals used along with Arabic text;Western Arabic numeralsandEastern Arabic numerals.In most of present-day North Africa, the usual Western Arabic numerals are used. Like Western Arabic numerals, in Eastern Arabic numerals, the units are always right-most, and the highest value left-most. Eastern Arabic numbers are written from left to right.

Letters as numerals

[edit]In addition, the Arabic Alpha bet can be used to represent numbers (Abjad numerals). This usage is based on theʾabjadīorder of the Alpha bet.أʾalifis 1,بbāʾis 2,جjīmis 3, and so on untilيyāʾ= 10,كkāf= 20,لlām= 30,...,رrāʾ= 200,...,غghayn= 1000. This is sometimes used to producechronograms.

History

[edit]

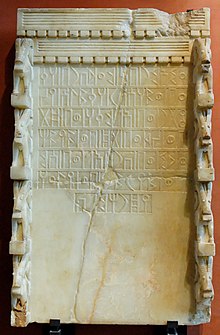

The Arabic Alpha bet can be traced back to theNabataean scriptused to writeNabataean Aramaic.The first known text in the Arabic Alpha bet is a late fourth-century inscription fromJabal Ram50 km east of‘AqabahinJordan,but the first dated one is a trilingual inscription atZebedinSyriafrom 512.[citation needed]However, theepigraphicrecord is extremely sparse, with only five certainlypre-Islamic Arabic inscriptionssurviving, though some others may be pre-Islamic. Later, dots were added above and below the letters to differentiate them. (The Aramaic language had fewer phonemes than the Arabic, and some originally distinct Aramaic letters had become indistinguishable in shape, so that in the early writings 14 distinct letter-shapes had to do duty for 28 sounds; cf. the similarly ambiguousBook Pahlavi.)

The first surviving document that definitely uses these dots is also the first surviving Arabicpapyrus(PERF 558), dated April 643, although they did not become obligatory until much later. Important texts were and still are frequently memorized, especially inQurʾan memorization.

Later still, vowel marks and the hamzah were introduced, beginning some time in the latter half of the 7th century, preceding the first invention ofSyriacandTiberian vocalizations.Initially, this was done by a system of red dots, said to have been commissioned in theUmayyadera byAbu al-Aswad al-Du'ali,a dot above =a,a dot below =i,a dot on the line =u,and doubled dots indicatednunation.However, this was cumbersome and easily confusable with the letter-distinguishing dots, so about 100 years later, the modern system was adopted. The system was finalized around 786 byal-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi.

Other tributes and Alpha bets written in Arabic dialects

[edit]Arabic dialects were written in different Alpha bets before the spread of the Arabic Alpha bet currently in use. The most important of these Alpha bets and inscriptions are theSafaiticinscriptions, amounting to 30,000 inscriptions discovered in theLevant desert.[16]

There are about 3,700 inscriptions inHismaicin central Jordan and northwest of the Arabian Peninsula, and Nabataean inscriptions, the most important of which are the Umm al-Jimal I inscription and theNumara inscription.[17]

Arabic printing

[edit]Medieval Arabic blockprintingflourished from the 10th century until the 14th. It was devoted only to very small texts, usually for use inamulets.

In 1514, followingJohannes Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in 1450, Gregorio de Gregorii, a Venetian, published an entire prayer-book in Arabic script; it was entitledKitab Salat al-Sawa'iand was intended for eastern Christian communities.[18]Between 1580 and 1586, type designerRobert Granjondesigned Arabic typefaces for CardinalFerdinando de' Medici,and theMedici Oriental Presspublished many Christian prayer and scholarly Arabic texts in the late 16th century.[19]

Maronitemonks at Maar Quzhay Monastery onMount Lebanonpublished the first Arabic books to use movable type in the Middle East. The monks transliterated the Arabic language usingSyriacscript.

AlthoughNapoleongenerally receives credit for introducing theprinting pressto Egypt during his invasion of the country in 1798, and though he did indeed bring printing presses and Arabic presses to print the French occupation's official newspaperAl-Tanbiyyah"The Courier", printing in the Arabic language had started several centuries earlier. A goldsmith (like Gutenberg) designed and implemented an Arabic-script movable-type printing-press in the Middle East. TheLebanese MelkitemonkAbdallah Zakherset up an Arabicprinting pressusingmovable typeat the monastery of Saint John at the town ofDhour El Shuwayrin Mount Lebanon, the first homemade press in Lebanon using Arabic script. He personally cut the type molds and did the founding of the typeface. The first book came off his press in 1734; this press continued in use until 1899.[20]

Computers

[edit]The Arabic Alpha bet can be encoded using severalcharacter sets,includingISO-8859-6,Windows-1256andUnicode,the latter of which contains the "Arabic segment", entries U+0600 to U+06FF. However, none of the sets indicates the form that each character should take in context. It is left to therendering engineto select the properglyphto display for each character.

Each letter has a position-independent encoding in Unicode, and the rendering software can infer the correct glyph form (initial, medial, final or isolated) from its joining context. That is the current recommendation. However, for compatibility with previous standards, the initial, medial, final and isolated forms can also be encoded separately.

Unicode

[edit]As of Unicode 16.0, the Arabic script is contained in the followingblocks:[21]

- Arabic(0600–06FF, 256 characters)

- Arabic Supplement(0750–077F, 48 characters)

- Arabic Extended-A(08A0–08FF, 96 characters)

- Arabic Extended-B(0870–089F, 42 characters)

- Arabic Extended-C(10EC0–10EFF, 7 characters)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-A(FB50–FDFF, 631 characters)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-B(FE70–FEFF, 141 characters)

- Rumi Numeral Symbols(10E60–10E7F, 31 characters)

- Indic Siyaq Numbers(1EC70–1ECBF, 68 characters)

- Ottoman Siyaq Numbers(1ED00–1ED4F, 61 characters)

- Arabic Mathematical Alphabetic Symbols(1EE00—1EEFF, 143 characters)

The basic Arabic range encodes the standard letters and diacritics but does not encode contextual forms (U+0621-U+0652 being directly based onISO 8859-6). It also includes the most common diacritics andArabic-Indic digits.U+06D6 to U+06ED encode Qur'anic annotation signs such as "end ofayah"ۖ and" start ofrub el hizb"۞. The Arabic supplement range encodes letter variants mostly used for writing African (non-Arabic) languages. The Arabic Extended-A range encodes additional Qur'anic annotations and letter variants used for various non-Arabic languages.

The Arabic Presentation Forms-A range encodes contextual forms and ligatures of letter variants needed for Persian,Urdu,Sindhi and Central Asian languages. The Arabic Presentation Forms-B range encodes spacing forms of Arabic diacritics, and more contextual letter forms. The Arabic Mathematical Alphabetical Symbols block encodes characters used in Arabic mathematical expressions.

See also the notes of the section onmodified letters.

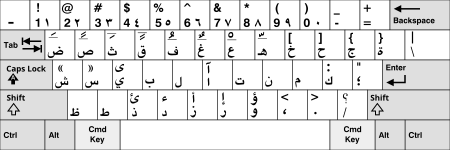

Keyboards

[edit]

Keyboards designed for different nations have different layouts, so proficiency in one style of keyboard, such as Iraq's, does not transfer to proficiency in another, such as Saudi Arabia's. Differences can include the location of non- Alpha betic characters.

All Arabic keyboards allow typing Roman characters, e.g., for the URL in aweb browser.Thus, each Arabic keyboard has both Arabic and Roman characters marked on the keys. Usually, the Roman characters of an Arabic keyboard conform to theQWERTYlayout, but inNorth Africa,whereFrenchis the most common language typed using the Roman characters, the Arabic keyboards areAZERTY.

To encode a particular written form of a character, there are extra code points provided in Unicode which can be used to express the exact written form desired. The rangeArabic presentation forms A(U+FB50 to U+FDFF) contain ligatures while the rangeArabic presentation forms B(U+FE70 to U+FEFF) contains the positional variants. These effects are better achieved in Unicode by using thezero-width joinerandzero-width non-joiner,as these presentation forms are deprecated in Unicode and should generally only be used within the internals of text-rendering software; when using Unicode as an intermediate form for conversion between character encodings; or for backwards compatibility with implementations that rely on the hard-coding of glyph forms.

Finally, the Unicode encoding of Arabic is inlogical order,that is, the characters are entered, and stored in computer memory, in the order that they are written and pronounced without worrying about the direction in which they will be displayed on paper or on the screen. Again, it is left to the rendering engine to present the characters in the correct direction, using Unicode'sbi-directional textfeatures. In this regard, if the Arabic words on this page are written left to right, it is an indication that the Unicode rendering engine used to display them is out of date.[22][23]

There are competing online tools, e.g. Yamli editor, which allow entry of Arabic letters without having Arabic support installed on a PC, and without knowledge of the layout of the Arabic keyboard.[24]

Handwriting recognition

[edit]The first software program of its kind in the world that identifies Arabic handwriting in real time was developed by researchers atBen-Gurion University(BGU).

The prototype enables the user to write Arabic words by hand on an electronic screen, which then analyzes the text and translates it into printed Arabic letters in a thousandth of a second. The error rate is less than three percent, according to Dr. Jihad El-Sana, from BGU's department of computer sciences, who developed the system along with master's degree student Fadi Biadsy.[25]

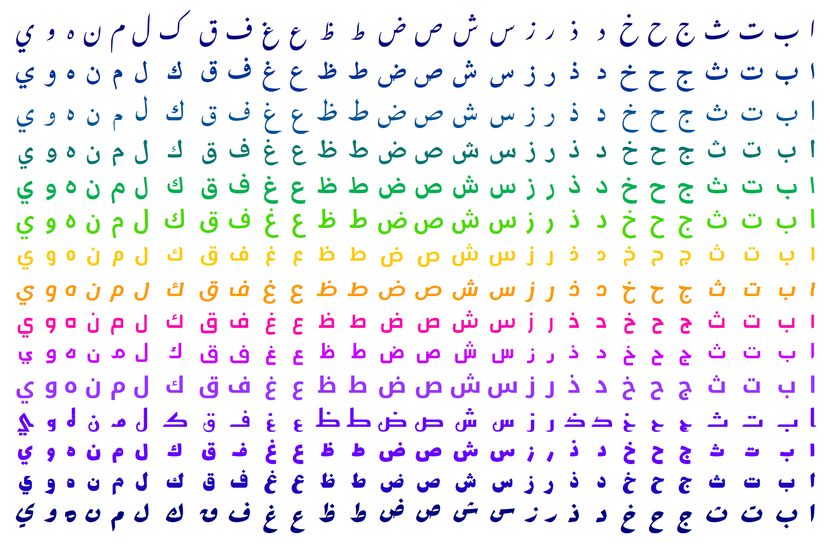

Variations

[edit]| يوهنملكقفغعظطضصشسزرذدخحجثتبا | hijā’ī sequence | |

|

• | NotoNastaliqUrdu |

| • | Scheherazade New | |

| • | Lateef | |

| • | NotoNaskhArabic | |

| • | Markazi Text | |

| • | NotoSansArabic | |

| • | El Messiri | |

| • | Lemonada | |

| • | Changa | |

| • | Mada | |

| • | NotoKufiArabic | |

| • | Reem Kufi | |

| • | Lalezar | |

| • | Jomhuria | |

| • | Rakkas | |

| غظضذخثتشرقصفعسنملكيطحزوهدجبا | abjadī sequence | |

|

• | Noto Nastaliq Urdu |

| • | Scheherazade New | |

| • | Lateef | |

| • | NotoNaskhArabic | |

| • | Markazi Text | |

| • | Noto Sans Arabic | |

| • | El Messiri | |

| • | Lemonada | |

| • | Changa | |

| • | Mada | |

| • | Noto Kufi Arabic | |

| • | Reem Kufi | |

| • | Lalezar | |

| • | Jomhuria | |

| • | Rakkas | |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^See the section onregional variationsin letter form.

References

[edit]- ^Daniels, Peter T.;Bright, William,eds. (1996).The World's Writing Systems.Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 559.ISBN978-0195079937.

- ^Zitouni, Imed (2014).Natural Language Processing of Semitic Languages.Springer Science & Business. p. 15.ISBN978-3642453588.

- ^abcMacdonald 1986,p. 117, 130, 149.

- ^ab(in Arabic)Alyaseer.netترتيب المداخل والبطاقات في القوائم والفهارس الموضوعيةOrdering entries and cards in subject indexesArchived23 December 2007 at theWayback MachineDiscussion thread(Accessed 2009-October–06)

- ^Macdonald 1986,p. 130.

- ^Rogers, Henry (2005).Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach.Blackwell Publishing. p. 135.

- ^"A list of Arabic ligature forms in Unicode".

- ^Depending on fonts used for rendering, the form shown on-screen may or may not be the ligature form.

- ^"Scheherazade New".SIL International.Retrieved4 February2022.

- ^"Arabic Dialect Tutorial"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 17 December 2008.Retrieved2 December2008.

- ^al Nassir, Abdulmunʿim Abdulamir (1985).Sibawayh the Phonologist(PDF)(in Arabic). University of New York. p. 80.Retrieved23 April2024.

- ^Notice sur les divers genres d'écriture ancienne et moderne des arabes, des persans et des turcs / par A.-P. Pihan.1856.

- ^File:Basmala kufi.svg – Wikimedia Commons

- ^File:Kufi.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

- ^File:Qur'an folio 11th century kufic.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

- ^"علم اللغة العربية • الموقع الرسمي للمكتبة الشاملة".15 December 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 15 December 2018.Retrieved16 March2024.

- ^Al-Jallad, Ahmad (6 January 2019),A Manual of the Historical Grammar of Arabic– via Academia.edu

- ^"294° anniversario della Biblioteca Federiciana: ricerche e curiosità sul Kitab Salat al-Sawai".Retrieved31 January2017.

- ^Naghashian, Naghi (21 January 2013).Design and Structure of Arabic Script.epubli.ISBN9783844245059.

- ^ Arabic and the Art of Printing – A Special SectionArchived29 December 2006 at theWayback Machine,by Paul Lunde

- ^"UAX #24: Script data file".Unicode Character Database.The Unicode Consortium.

- ^For more information about encoding Arabic, consult the Unicode manual available atThe Unicode website

- ^See alsoMultilingual Computing with Arabic and Arabic Transliteration: Arabicizing Windows Applications to Read and Write Arabic & Solutions for the Transliteration Quagmire Faced by Arabic-Script LanguagesandA PowerPoint Tutorial (with screen shots and an English voice-over) on how to add Arabic to the Windows Operating System.Archived11 September 2011 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Yamli in the News".

- ^"Israel 21c".14 May 2007.

Sources

[edit]- Macdonald, Michael C. A.(1986). "ABCs and letter order in Ancient North Arabian".Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies(16): 101–168.

External links

[edit]- Shaalan, Khaled; Raza, Hafsa (August 2009)."NERA: Named entity recognition for Arabic".Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology.60(8): 1652–1663.doi:10.1002/asi.21090.