Arrangement

Inmusic,anarrangementis a musical adaptation of an existingcomposition.[1]Differences from the original composition may includereharmonization,melodic paraphrasing,orchestration,orformaldevelopment. Arranging differs fromorchestrationin that the latter process is limited to the assignment of notes to instruments forperformanceby anorchestra,concert band,or othermusical ensemble.Arranging "involves adding compositional techniques, such as newthematic materialforintroductions,transitions,ormodulations,andendings.Arranging is the art of giving an existing melody musical variety ".[2]Injazz,a memorized (unwritten) arrangement of a new or pre-existing composition is known as ahead arrangement.[3]

Classical music[edit]

Arrangement andtranscriptionsofclassicalandserious musicgo back to the early history ofclassical music.

Eighteenth century[edit]

J. S. Bachfrequently made arrangements of his own and other composers' pieces. One example is the arrangement that he made of the Prelude from hisPartita No.3for soloviolin,BWV1006.

Bach transformed this solo piece into an orchestralSinfoniathat introduces hisCantata BWV29."The initial violin composition was in Emajor but both arranged versions are transposed down to D, the better to accommodate the wind instruments ".[4]

"The transformation of material conceived for a single string instrument into a fully orchestratedconcerto-type movement is so successful that it is unlikely that anyone hearing the latter for the first time would suspect the existence of the former ".[5]

Nineteenth and twentieth centuries[edit]

Piano music[edit]

In particular, music written for thepianohas frequently undergone this treatment, as it has been arranged for orchestra, chamber ensemble, orconcert band.[6]Beethovenmade an arrangement of hisPiano Sonata No.9forstring quartet.Conversely, he also arranged hisGrosse Fuge(one of hislate string quartets) forpiano duet.The American composerGeorge Gershwin,due to his own lack of expertise in orchestration, had hisRhapsody in Bluearranged and orchestrated byFerde Grofé.[7]

Erik Satiewrote his threeGymnopédiesfor solo piano in 1888.

Eight years later,Debussyarranged two of them, exploiting the range of instrumentaltimbresavailable in a late 19th-century orchestra. "It was Debussy whose 1896 orchestrations of the Gymnopédies put their composer on the map."[8]

Pictures at an Exhibition,asuiteof ten piano pieces byModest Mussorgsky,has been arranged over twenty times, notably byMaurice Ravel.[9]Ravel's arrangement demonstrates an "ability to create unexpected, memorable orchestral sonorities".[10]In the second movement, "Gnomus", Mussorgsky's original piano piece simply repeats the following passage:

Ravel initially orchestrates it as follows:

Repeating the passage, Ravel provides a fresh orchestration "this time with thecelesta(replacing thewoodwinds) accompanied by stringglissandoson thefingerboard".[10]

Songs[edit]

A number ofFranz Schubert's songs, originally for voice with piano accompaniment, were arranged by other composers. For example, his "highly charged" and "graphic" song "Erlkönig"(" The Erl King ") has a piano introduction that conveys" unflagging energy "from the start.[11]

The arrangement of this song byHector Berliozuses strings to convey faithfully the driving urgency and threatening atmosphere of the original.

Berlioz adds colour in bars6–8 through the addition ofwoodwind,horns,and atimpani.With typical flamboyance, Berlioz adds spice to the harmony in bar6 with an Eflat in the horn part, creating ahalf-diminished seventh chordwhich is not in Schubert's original piano part.

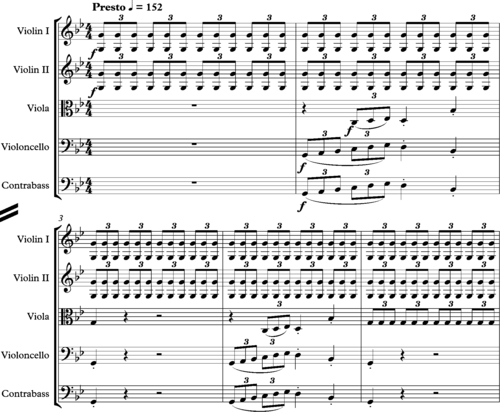

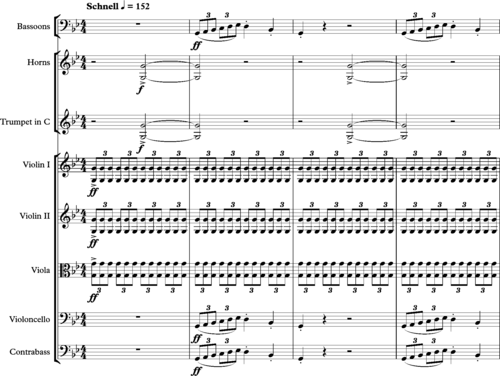

There are subtle differences between this and the arrangement of the song byFranz Liszt.The upper string sound is thicker, with violins andviolasplaying the fierce repeatedoctavesinunisonandbassoonscompensating for this bydoublingthecellosandbasses.There are no timpani, buttrumpetsand horns add a small jolt to the rhythm of the opening bar, reinforcing the bare octaves of thestringsby playing on the second main beat.

Unlike Berlioz, Liszt does not alter the harmony, but changes the emphasis somewhat in bar6, with the note A in theoboesandclarinetsgrating against rather than blending with the G in the strings.

"Schubert has come in for his fair share of transcriptions and arrangements. Most, like Liszt's transcriptions of theLiederor Berlioz's orchestration forErlkönig,tell us more about the arranger that about the original composer, but they can be diverting so long as they are in no way a replacement for the original ".[12]

Gustav Mahler'sLieder eines fahrenden Gesellen( "Songs of a Wayfarer" ) were originally written for voice with piano accompaniment. The composer's later arrangement of the piano part shows a typical ear for clarity and transparency in rewriting for an ensemble. Below is the original piano version of the closing bars of the second song, "Gieng heit' Morgen über's Feld".

The orchestration shows Mahler's attention to detail in bringing out differentiated orchestralcolourssupplied by woodwind, strings and horn. He uses aharpto convey the originalarpeggiossupplied by the left hand of the piano part. He also extracts a descendingchromaticmelodic line, implied by the left hand in bars2–4 (above), and gives it to the horn.

Popular music[edit]

Popular musicrecordings often include parts forbrasshorn sections,bowed strings,and other instruments that were added by arrangers and not composed by the originalsongwriters.Some pop arrangers even add sections using fullorchestra,though this is less common due to the expense involved. Popular music arrangements may also be considered to includenew releases of existing songswith a new musical treatment. These changes can include alterations totempo,meter,key,instrumentation,and other musical elements.

Well known examples includeJoe Cocker's version ofthe Beatles' "With a Little Help from My Friends",Cream's "Crossroads",andIke and Tina Turner's version ofCreedence Clearwater Revival's "Proud Mary".The American groupVanilla Fudgeand the British groupYesbased their early careers on radical rearrangements ofcontemporary hits.[13][14]Bonnie Pointer performeddiscoandMotown-styled versions of "Heaven Must Have Sent You".[15]Remixes,such as indance music,can also be considered arrangements.[16]

Jazz[edit]

Arrangements for smalljazz combosare usually informal, minimal, and uncredited. Larger ensembles have generally had greater requirements for notated arrangements, though the earlyCount Basiebig bandis known for its manyheadarrangements, so called because they were worked out by the players themselves, memorized ( "in the player'shead"), and never written down.[17]Most arrangements for big bands, however, were written down and credited to a specific arranger, as with arrangements bySammy NesticoandNeal Heftifor Count Basie's later big bands.[18]

Don Redmanmade innovations in jazz arranging as a part ofFletcher Henderson's orchestra in the 1920s. Redman's arrangements introduced a more intricate melodic presentation andsoliperformances for various sections of the big band.[19]Benny Carterbecame Henderson's primary arranger in the early 1930s, becoming known for his arranging abilities in addition to his previous recognition as a performer.[19]Beginning in 1938,Billy Strayhornbecame an arranger of great renown for theDuke Ellingtonorchestra.Jelly Roll Mortonis sometimes considered the earliest jazz arranger. While he toured around the years 1912 to 1915, he wrote down parts to enable "pickup bands"to perform his compositions.

Big-band arrangements are informally calledcharts.In the swing era they were usually either arrangements of popular songs or they were entirely new compositions.[20]Duke Ellington's andBilly Strayhorn's arrangements for the Duke Ellington big band were usually new compositions, and some ofEddie Sauter's arrangements for theBenny Goodmanband andArtie Shaw's arrangements for his own band were new compositions as well. It became more common to arrange sketchy jazz combo compositions for big band after the bop era.[21]

After 1950, the big bands declined in number. However, several bands continued and arrangers provided renowned arrangements.Gil Evanswrote a number of large-ensemble arrangements in the late 1950s and early 1960s intended for recording sessions only. Other arrangers of note includeVic Schoen,Pete Rugolo,Oliver Nelson,Johnny Richards,Billy May,Thad Jones,Maria Schneider,Bob Brookmeyer,Lou Marini,Nelson Riddle,Ralph Burns,Billy Byers,Gordon Jenkins,Ray Conniff,Henry Mancini,Ray Reach,Vince Mendoza,andClaus Ogerman.

In the 21st century, the big-band arrangement has made a modest comeback.Gordon Goodwin,Roy Hargrove,andChristian McBridehave all rolled outnew big bandswith both original compositions and new arrangements of standard tunes.[22]

For instrumental groups[edit]

Strings[edit]

Thestring sectionis a body of instruments composed of various bowed stringed instruments. By the 19th centuryorchestral musicin Europe had standardized the string section into the following homogeneous instrumental groups: firstviolins,second violins (the same instrument as the first violins, but typically playing anaccompanimentorharmony partto the first violins, and often at a lower pitch range),violas,cellos,anddouble basses.The string section in a multi-sectioned orchestra is sometimes referred to as the "string choir".[23]

Theharpis also a stringed instrument, but is not a member of norhomogeneouswith the violin family, and is not considered part of the string choir.Samuel Adlerclassifies theharpas a plucked string instrument in the same category as theguitar(acousticorelectric),mandolin,banjo,orzither.[24]Like the harp, these instruments do not belong to the violin family and are not homogeneous with the string choir. In modern arranging these instruments are considered part of the rhythm section. Theelectric bassand upright string bass—depending on the circumstance—can be treated by the arranger as either string section orrhythm sectioninstruments.[25]

A group of instruments in which each member plays a unique part—rather than playing in unison with other like instruments—is referred to as achamber ensemble.[26]A chamber ensemble made up entirely of strings of the violin family is referred to by its size. Astring trioconsists of three players, a string quartet four, astring quintetfive, and so on.

In most circumstances the string section is treated by the arranger as one homogeneous unit and its members are required to play preconceived material rather thanimprovise.

A string section can be utilized on its own (this is referred to as a string orchestra)[27]or in conjunction with any of the other instrumental sections. More than one string orchestra can be utilized.

A standard string section (vln., vln 2., vla., vcl, cb.) with each section playing unison allows the arranger to create a five-part texture. Often an arranger will divide each violin section in half or thirds to achieve a denser texture. It is possible to carry this division to its logical extreme in which each member of the string section plays his or her own unique part.

Size of the string section[edit]

Artistic, budgetary and logistical concerns, including the size of the orchestra pit or hall will determine the size and instrumentation of a string section. TheBroadwaymusicalWest Side Story,in 1957, was booked into the Winter Garden theater; composerLeonard Bernsteindisliked the playing of "house" viola players he would have to use there, and so he chose to leave them out of the show's instrumentation; a benefit was the creation of more space in the pit for an expanded percussion section.[28]

George Martin,producerand arranger forthe Beatles,warns arrangers about theintonationproblems when only two like instruments play in unison: "After a string quartet, I do not think there is a satisfactory sound for strings until one has at least three players on each line... as a rule two stringed instruments together create a slight 'beat' which does not give a smooth sound."[29]Different music directors may use different numbers of string players and different balances between the sections to create different musical effects.

While any combination and number of string instruments is possible in a section, a traditional string section sound is achieved with a violin-heavy balance of instruments.

| Reference | Author | Section size | Violins | Violas | Celli | Basses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Arranged By Nelson Riddle"[30] | Nelson Riddle | 12 players | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 15 players | 9 | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 16 players | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 20 players | 12 | 4 | 4 | 0 | ||

| 30 players | 18 | 6 | 6 | 0 | ||

| "The Contemporary Arranger"[31] | Don Sebesky | 9 players | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 12 players | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 16 players | 12 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| 20 players | 12 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

Further reading[edit]

| Name | Author |

|---|---|

| Inside the score: A detailed analysis of 8 classic jazz ensemble charts by Sammy Nestico, Thad Jones and Bob Brookmeyer | Rayburn Wright |

| Sounds and Scores: A Practical Guide to Professional Orchestration | Henry Mancini |

| The Contemporary Arranger | Don Sebesky |

| The Study of Orchestration | Samuel Adler |

| Arranged by Nelson Riddle | Nelson Riddle |

| Instrumental Jazz Arranging: A Comprehensive and Practical Guide | Mike Tomaro |

| Modern Jazz Voicings: Arranging for Small and Medium Ensemble | Ted Pease, Ken Pullig |

| Arranging for Large Jazz Ensemble | Ted Pease, Dick Lowell |

| Arranging concepts complete: the ultimate arranging course for today's music | Dick Grove |

| The complete arranger | Sammy Nestico |

| Arranging Songs: How to Put the Parts Together | Rikky Rooksby |

See also[edit]

- Transcription (music)

- Instrumentation (music)

- Orchestration

- Reduction (music)

- Musical notation

- American Society of Music Arrangers and Composers

- Electronic keyboard(or Electronic Music Arranger), which allows for live music arrangement

- List of music arrangers

- List of jazz arrangers

- Category:Music arrangers

References[edit]

- ^"Arrangement".Britannica.Retrieved16 October2020.

- ^(Corozine 2002, p. 3)

- ^Cook, Richard (2005).Richard Cook's Jazz Encyclopedia.London: Penguin Books. p. 20.ISBN978-0-141-02646-6.

- ^Mincham, J. (2016) the Cantatas of Johan Sebastian Bach.http:// jsbachcantatas /documents/chapter-85-bwv-29/Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^Mincham, J. (2016),The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach.http:// jsbachcantatas /documents/chapter-85-bwv-29/Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^Arrangement,Encyclopædia Britannica online

- ^Greenberg, Rodney.George Gershwin,p. 66. Phaidon Press, 1998.ISBN0-7148-3504-8.

- ^Taruskin, R. (2010, p. 70)The Oxford History of Western Music, Music in the early Twentieth Century.Oxford University Press.

- ^Partial list of orchestral arrangements to Pictures at an Exhibition

- ^abOrenstein, A. (2016, p. VIII. Preface toMussorgsky-Ravel, Pictures at an Exhibition.Miniature score, London, Eulenburg.

- ^Newbould, B. (1997, p. 57)Schubert: the Music and the Man.London, Gollancz.

- ^Newbould, B. (1997, p. 467)Schubert: the Music and the Man.London, Gollancz.

- ^Vanilla Fudge covers(classic bands website)

- ^Close To the Edge – The Story of Yes,Chris Welch, Omnibus Press, 1999/2003/2008 pages 33-34

- ^Bonnie Pointer bio(IMDbwebsite)

- ^The Remix Manual: The Art and Science of Dance Music Remi xing with Logic,Simon Langford (Elsevier, 2011,ISBN978-0-240-81458-2) page 47

- ^Randel 2002, p. 294

- ^Swing music historyand the big bands (Jazz in America website)

- ^ab"JAZZ A Film By Ken Burns: Selected Artist Biography - Fletcher Henderson".PBS. 25 September 1934.Retrieved18 October2013.

- ^Giddins, Gary & Scott DeVeaux (2009).Jazz.New York: W.W. Norton & Co,ISBN978-0-393-06861-0

- ^Bailey, C. Michael (11 April 2008)."Miles Davis, Miles Smiles, and the Invention of Post Bop".All About Jazz.Retrieved23 February2013.

- ^"Carrington and Correa Among Jazz Winners"– LATimes Blog, Feb. 2012

- ^Adler, Samuel(2002).The Study of Orchestration.New York: W. W. Norton. pp.111.ISBN9780393975727.

- ^Adler, Samuel (2002).The Study of Orchestration.New York: W. W. Norton. pp.89.ISBN9780393975727.

- ^Sebesky, Don (1975).The Contemporary Arranger.New York: Alfred Pub. p. 117.

- ^"Oxford Music Online".Retrieved22 July2011.

- ^"String orchestra".Collins English Dictionary(11th ed.).Retrieved21 October2012.

- ^Burton, Humphrey."Leonard Bernstein by Humphrey Burton, Chapter 26".Archived fromthe originalon 29 June 2011.Retrieved22 July2011.

- ^Martin, George(1983).Making Music: the Guide to Writing, Performing & Recording.New York: W. Morrow. p. 82.

- ^Riddle, Nelson (1985).Arranged By Nelson Riddle.Secaucus, NJ: Warner Brothers Publications Inc. p. 124.

- ^Sebesky, Don (1975).The Contemporary Arranger.New York: Alfred Pub. pp. 127–129.

- Sources

- Corozine, Vince (2002).Arranging Music for the Real World: Classical and Commercial Aspects.Pacific, MO: Mel Bay.ISBN0-7866-4961-5.OCLC50470629.

- Kers, Robert de (1944).Harmonie et orchestration pour orchestra de danse.Bruxelles: Éditions musicales C. Bens. vii, 126 p.

- Kidd, Jim (1987).Unsung Heroes, the Jazz Arrangers, from Don Redman to Sy Oliver: [text with recorded examples for a presentation] Prepared on the Occasion of the 16th Annual Canadian Collectors' Congress, 25 April 1987, Toronto, Ont.Toronto: Canadian Collectors' Congress. Photo-reproduced text ([6] leaves) with audiocassette of recorded illustrative musical examples.

- Randel, Don Michael (2002).The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians.ISBN0-674-00978-9.

External links[edit]

- An oral history of pop music arranging, compiled byRichard Niles:Part 1,Part 2,Part 3