Atum

| Atum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

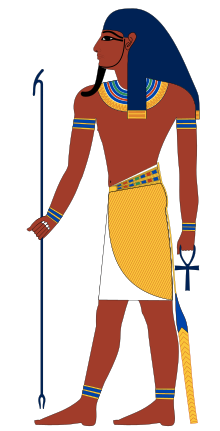

Atum is shown as a man with a was-scepter to show his power, and an Ankh to symbolize his association to life. He is only later and rarely shown with a Double Crown. | ||||

| Name inhieroglyphs | ||||

| Major cult center | Heliopolis | |||

| Genealogy | ||||

| Consort | Iusaaset[1]orNebethetepet[2] | |||

| Children | ShuandTefnut | |||

Atum(/ɑ.tum/,Egyptian:jtm(w)ortm(w),reconstructed[jaˈtaːmuw];CopticⲁⲧⲟⲩⲙAtoum),[3][4]sometimes rendered asAtemorTem,is the primordial God inEgyptian mythologyfrom whom all else arose. He created himself and is the father ofShuandTefnut,the divine couple, who are the ancestors of the other Egyptian deities. Atum is also closely associated with the evening sun. As a primordial god and as the evening sun, Atum haschthonicandunderworldconnections.[5]Atum was relevant to the ancient Egyptians throughout most of Egypt's history. He is believed to have been present in ideology as early aspredynastictimes, becoming even more prevalent during theOld Kingdomand continuing to be worshiped through theMiddleandNew Kingdom,though he becomes overshadowed byRearound this time.

Name[edit]

Atum's name is thought to be derived from the verbtmwhich means 'to complete' or 'to finish'. Thus, he has been interpreted as being the "complete one" and also the finisher of the world, which he returns to watery chaos at the end of the creative cycle. As creator, he was seen as the progenitor of the world, the deities and universe having received his vital force orka.[6]

Origins[edit]

Atum is one of the most important and frequently mentioned deities from earliest times, as evidenced by his prominence in thePyramid Texts,where he is portrayed as both a creator and father to the king throughout the collection of spells.[6]Several writings contradict how Atum was brought into existence. According to theHeliopolitanview, Atum originally existed in hiseggwithin the primeval waters, being born during the primordial flood, becoming the source of everything that was created after him. The Memphites (priests of Memphis), on the other hand, believed thatPtahcreated Atum in a more intellectual way, using his speech and thought, as told on theShabaka Stone.[7]

Role[edit]

In theHeliopolitan creation myth,Atum was considered to be thefirst god,havingcreated himself,sitting on a mound (benben) (or identified with the mound itself), and rose from theprimordial waters(Nu).[8]Early myths state that Atum created the godShuand goddessTefnutby spitting them out of his mouth.[9][10]One text debates that Atum did not create Shu and Tefnut by spitting them out of his mouth by means of saliva and semen, but rather by Atum's lips.[11]Another writing describes Shu and Tefnut being birthed by Atum's hand. That same writing states that Atum's hand is the title of the god's wife based on her Heliopolitan beginning.[12]Other myths state Atum created bymasturbation,with the hand he used in this act that may be interpreted as the female principle inherent within him[13]and identified with goddesses such as Hathor orIusaaset.Yet other interpretations state that he has made union with his shadow.[14]

In theOld Kingdom,the Egyptians believed that Atum lifted the dead king's soul from his pyramid to the starry heavens.[10]He was also asolar deity,associated with the primary sun godRa.Atum was linked specifically with the evening sun, while Ra or the closely linked godKhepriwere connected with the sun at morning and midday.[15]

In theCoffin Texts,Atum has a vital conversation withOsirisin which he describes the end of the universe as a time in which everything will cease to exist with the exception of the elements of the primordial waters, stating that after millions of years he and Osiris would be the only ones to survive the end of time as serpents.[16]He claims that he will destroy everything he created in the beginning of existence and bring it back to Nu, the primeval waters,[17]thus describing the belief that the gods and goddesses would one day cease to exist outside of the primeval waters.[16]

In theBook of the Dead,which was still current in the Graeco-Roman period, the sun god Atum is said to have ascended fromchaos-waters with the appearance of asnake,the animal renewing itself every morning.[18][19][20]

Atum is the god ofpre-existenceandpost-existence.In the binarysolar cycle,the serpentine Atum is contrasted with the scarab-headed godKhepri—the young sun god, whose name is derived from the Egyptianḫpr"to come into existence". Khepri-Atum encompassed sunrise and sunset, thus reflecting the entire cycle of morning and evening.[21]

Relationship to other gods[edit]

Atum was aself-created deity,the first being to emerge from the darkness and endlesswatery abyssthat existed before creation. A product of the energy and matter contained in this chaos, he created his children—the first deities, out of loneliness. He produced from his own sneeze, or in some accounts, semen,Shu,the god of air, andTefnut,the goddess of moisture. The brother and sister, curious about the primeval waters that surrounded them, went to explore the waters and disappeared into the darkness. Unable to bear his loss, Atum sent a fiery messenger, theEye of Ra,to find his children. The tears of joy he shed upon their return were the first human beings.[22]

Iconography[edit]

Atum is usually depicted in anthropomorphic form, wearing either theroyal head-clothor the dualwhiteandred crownofUpperandLower Egypt,reinforcing his connection with kingship. He is typically depicted sitting on a throne and will usually be represented with the head of aramwhen he is mentioned within the context of his connection to theunderworldand his solar attributes.[23]Sometimes he is also shown as aserpent,the form he returns to at the end of the creative cycle, and also occasionally as amongoose,lion,bull,lizard,orape.[6]When he is represented as a solar deity, he can also be depicted as ascaraband when in reference to his primeval origins he is also seen depicted as the primeval mound.[23]

Worship[edit]

Atum was worshipped throughout Egypt's history; the center of his worship centered on the city ofHeliopolis(Egyptian:AnnuorIunu).[6]The only surviving remnant of Heliopolis is the Temple of Ra-Atumobelisklocated in Al-Masalla ofAl-Matariyyah, Cairo.It was erected bySenusret Iof theTwelfth Dynasty,and still stands in its original position.[24]In the Old Kingdom Atum was at the center of the Egyptian belief system, being partly responsible for the origins of existence, having created himself and everything else out of the primordial waters. He is believed to have been present in ideology as early as predynastic times, becoming even more prevalent during theOld Kingdomas indicated by the pyramid texts in which he appears frequently. He continues to be found in theMiddle Kingdom,during which he is depicted in theBook of the Deadin which he appears in spells to help with the journey to the Afterlife. Later, in theNew Kingdom,there cults attributed to Atum, such as the Theban royal high priestesses known as theDivine Adoratrices of Amunwho acted as the Hand of Atum in temple rituals at the time.[25]Rewould take centerstage later on but as Atum was overshadowed, the people of ancient Egypt would continue to worship him through cultic rituals in which he is depicted as having close relationships with the king, as well as being represented through lizards on smallreliquariesandamuletscloser to theLate Period.[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Wilkinson 2003,p. 150.

- ^Wilkinson 2003,p. 156.

- ^"Coptic Dictionary Online".corpling.uis.georgetown.edu.Retrieved2017-09-21.

- ^"Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae".Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.Retrieved2017-09-21.

- ^Richard H. Wilkinson (2003).The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt.Internet Archive. Thames & Hudson. pp. 98–101.ISBN978-0-500-05120-7.

- ^abcdWilkinson 2003,p. 99–101.

- ^Wilkinson, Richard H.The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt.New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 17–18.ISBN0-500-05120-8.OCLC51668000.

- ^The British Museum."Picture List"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2013-09-22.Retrieved2012-04-04.

- ^Watterson, Barbara (2003).Gods of ancient Egypt.Stroud: Sutton.ISBN0-7509-3262-7.OCLC53242963.

- ^ab"The Egyptian Gods: Atum".Archived fromthe originalon 2002-08-17.Retrieved2006-12-30.

- ^Lloyd 2012,p. 409.

- ^Lloyd 2012,p. 150.

- ^Wilkinson 2003,p. 17-18, 99.

- ^"The Egyptian Creation Myth — How the World Was Born".Experience Ancient Egypt.Archived fromthe originalon 2010-01-09.

- ^Wilkinson 2003,p. 205.

- ^abWilkinson, Richard H.The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt.Thames & Hudson. pp. 20–21.ISBN0-500-05120-8.OCLC51668000.

- ^Wyatt, Nicolas (2001).Space and Time in the Religious Life of the Near East.Bloomsbury Publishing.ISBN978-0-567-04942-1.OCLC893336455.

- ^Toorn, Becking & Horst 1999,p. 121.

- ^Ellis, Normandi (1995-01-01).Dreams of Isis: A Woman's Spiritual Sojourn.Quest Books. p. 128.ISBN9780835607124.

- ^Bernal, Martin (1987).Black Athena: The linguistic evidence.Rutgers University Press. p. 468.ISBN9780813536552.

- ^Toorn, Becking & Horst 1999,p. 123.

- ^Pinch, Geraldine (2004).Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt.Oxford University Press. pp. 63–64

- ^abcWilkinson, Richard H.The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 100–101.ISBN0-500-05120-8.OCLC51668000.

- ^Butler, John Anthony (2019-01-22).John Greaves, Pyramidographia and Other Writings, with Birch's Life of John Greaves.Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 154.ISBN978-1-5275-2668-6.

- ^Pinch, Geraldine (2011).Handbook of Egyptian mythology.ABC-CLIO. pp. 31–32.ISBN978-1-84972-853-9.OCLC730934370.

Bibliography[edit]

- Lloyd, Aylward M. (2012-11-12).Gods Priests & Men.Routledge.doi:10.4324/9780203038277.ISBN978-1-136-15386-0.

- Toorn, Karel van der; Becking, Bob; Horst, Pieter Willem van der (1999).Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible.Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.ISBN9780802824912.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003).The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.Thames and Hudson.ISBN0500051208.

Further reading[edit]

- Myśliwiec, Karol(1978).Studien zum Gott Atum. Band I, Die heiligen Tiere des Atum.Gerstenberg.ISBN978-3806780338.

- Myśliwiec, Karol (1979).Studien zum Gott Atum. Band II, Name, Epitheta, Ikonographie.Gerstenberg.ISBN978-3806780406.