Augustus' Eastern policy

| Augustus' Eastern policy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part ofRoman–Parthian Wars | |||||||

The empire of theParthians | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Empire | Parthians,Armenians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Augustus, Agrippa, Tiberius, Gaius Caesar |

Phraates IV, Phraates V | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4/5Roman legionstotaling about 20,000/25,000 armed men in addition toauxilia | |||||||

Augustus' Eastern policyrepresents the political-strategic framework of the eastern imperial borders of theRoman Empireat the time ofAugustus'principate,following the occupation ofEgyptat the end of thecivil war between Octavian and Mark Antony(31-30 BC).

War of occupation[edit]

Historical context[edit]

Almost in spite of Augustus' seemingly peaceful disposition, his principate was the most troubled by wars than those of most of his successors. OnlyTrajanandMarcus Aureliusfound themselves fighting simultaneously on several fronts, as did Augustus. Under Augustus, in fact, almost every frontier was involved, from the northern ocean to the shores of Pontus, from the mountains of Cantabria to the desert of Ethiopia, in a preordained strategic plan to complete conquests along the entireMediterranean basinand in Europe, with the borders moving further north along theDanubeand further east along theElbe(instead of theRhine).[1]

Augustus' campaigns were carried out with the aim of consolidating the disorganized conquests of the Republican age, which made numerous annexations of new territories essential. While the East could remain more or less asAntonyandPompeyhad left it, in Europe between the Rhine and the Black Sea a new territorial reorganization was needed so as to ensure internal stability and, at the same time, more defensible borders.

Prior situation[edit]

Mark Antony's campaigns inParthiahad been unsuccessful. Not only had Rome's honor not been avenged following the defeat suffered by ConsulMarcus Licinius CrassusatCarrhaein 53 B.C.E., but also Roman armies had been defeated again in enemy territory, andArmeniaitself had entered the Roman sphere of influence only briefly. It was not until the end of thecivil war,with theBattle of Actium(in 31 B.C.) and the occupation ofEgypt(in 30 B.C.), that Octavian was able to concentrate on the Parthian problem and on the arrangement of the entire Roman East. The Roman world expected perhaps a series of campaigns and even the conquest of Parthia itself,[2]considering thatAugustuswas the adopted son of the greatCaesar,[3]who had planned a campaign in the footsteps of theMacedonian.[4][5][6]

Forces in the field[edit]

Augustuswas able to field an army composed of numerous legions:

- for the Easternfront:Legio III Gallica,Legio VI Ferrata,Legio X FretensisandLegio XII Fulminata.[7][8]

Eastern Policy[edit]

West of the Euphrates[edit]

West of theEuphrates,Augustus tried to reorganize the Roman East, either by incorporating some vassal states and turning them intoRoman provinces(such asAmyntas' Galatia in 25 B.C, orHerod Archelaus'Judaeain 6 (after there had been some initial unrest in 4 B.C. upon the death ofHerod the Great), or by strengthening old alliances with local kings who had become "client kings of Rome" (as happened toArchelaus,king ofCappadocia,Asander,king of theBosporan Kingdom,Polemon I,king ofPontus,[9]as well as the rulers ofEmesa,Iturea,[10]Commagene,Cilicia,Chalcis,Nabatea,Iberia,ColchisandAlbania).[11]

East of the Euphrates[edit]

East of the Euphrates, in Armenia, Parthia, and Media, Augustus aimed to achieve the greatest political interference without intervening with costly military action. In fact, Octavian aimed to resolve the conflict with theParthiansdiplomatically, with the Parthian kingPhraates IVreturning in 20 B.C. thestandardslost by Crassus at theBattle of Carrhaein 53 B.C. He could have turned against Parthia to avenge the defeats suffered byCrassusandAntony;instead, he believed a peaceful coexistence of the two empires was possible, with the Euphrates as the boundary for each other's areas of influence. In fact, both empires had more to lose from a defeat than they could realistically hope to gain from a victory. Throughout his long principate, Augustus concentrated his main military efforts in Europe. The focal point in the East, however, was thekingdom of Armenia,which, because of its geographical location, had been the subject of contention between Rome and Parthia for the past fifty years. He aimed to make Armenia a Roman buffer state, with the enthronement of a king appreciated by Rome, and if necessary imposed by force of arms.[12]

First Parthian crisis: Augustus recovers the standards of Crassus (23-20 BC)[edit]

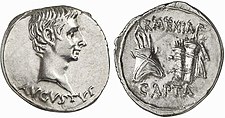

| Augustus:denarius[13] | |

|---|---|

| |

| AUGUSTUS,head ofAugustustoward the right; | ARMENIACAPTA,an Armeniantiara,a bow and quiver with arrows. |

| Silver, 3.77 g; minted in 19-18 B.C., after Armenia returned to the area of Roman influence. | |

| Augustus:denarius[14] | |

|---|---|

| |

| S • P • Q • R•IMP•CAESARI•AVG•COS • XI•TRI • POT • VI•, head ofAugustustoward the right; | CIVIB• ET • SIGN • MILIT • A •PA-RT• RECVP •,triumphal archofAugustus:above the contralateral arch there is aquadriga;above the lateral arches there is a figure of each; on the left there is a figure turned to the right holding asignumin his right hand raised toward the sky; on the right, on the other hand, there is a figure facing left, holding aneaglein his right and a bow in his left. |

| Silver, 3.86 gr, 6 h; Spanish mint ofTarraco,minted in 18 BC | |

In 23 B.C.E., shortly afterMarcus Vipsanius Agrippawas sent to the East as deputy regent of the emperorAugustushimself, ambassadors sent by the king of theParthiansarrived in Rome, demanding that bothTiridates II,the former Parthian ruler (who had taken refuge in Rome since 26 B.C.E.), and the new king's young son be handed over to him. Augustus, while refusing to hand over the former, which could still come in handy in the future, decided to release the son of KingPhraates IV,on the condition that the standards ofMarcus Licinius Crassusand the prisoners of war from 53 B.C. be returned to the Roman state.[15]

In Armenia, meanwhile, a chronic division reigned among the nobles: the pro-Roman party had sent an embassy to Augustus demanding a trial of KingArtaxias II,his deposition and the replacement on the throne of Armenia of his younger brother,Tigranes III,who had lived inRomesince 29 BCE. At the end of 21 B.C., Augustus ordered his stepsonTiberius,who was then twenty-one years old, to lead a legionary army from theBalkansto the East,[16]with the task of placingTigranes IIIon the Armenian throne and recovering the imperial standards.

Augustus himself traveled to the East. His arrival and the approach of Tiberius' army produced the desired effect on the Parthian king. Faced with the danger of a Roman invasion that could have cost him the throne,Phraates IVdecided to relent and, while risking displeasing his own people, returned the standards and the surviving Roman prisoners. Augustus was proclaimed imperator for the ninth time.[17]The return of the standards and prisoners was a diplomatic success comparable to the best victories achieved on the battlefield.

—Suetonius,Augustus,21.

—Suetonius,Augustus,43.

Augustus,who had thus decided, upon recovering the standards lost atCarrhae,to abandon the aggressive policy thatCaesarandAntonyhad pursued in the East, was able to establish friendly relations with the neighboringParthian Empire.He could have avenged the defeat and betrayal suffered byCrassusin 53 BC. Instead, he considered a peaceful coexistence of the two empires to be convenient, with theEuphratesas the boundary of each other's domains.

Attempting to subdueParthiawould have required considerable manpower and financial resources, as well as the possibility of shifting theempire's focus from theMediterraneanfurther east, now thatAugustuswas intent on concentrating his efforts on theEuropeanfront. Relations between the Parthians depended, therefore, more on diplomacy than on war. Only in the East did Rome face another great "superpower of classical antiquity," although not comparable to the strength and size of Rome.

The friendly relations established between Rome and theParthianseventually favored the pro-Roman party in neighboring Armenia, and before Tiberius reached theEuphrates,Artaxias IIwas assassinated by his own courtiers.Tiberius,having entered the country without encountering resistance and in the presence of thelegions,solemnly placed the royal diadem onTigranes III's head, andAugustuswas able to announce that he had conquered Armenia, while refraining from anne xing it.[18]

Second Parthian crisis (1 B.C.-4)[edit]

In 1 BC,Artavasdes III,a pro-Roman king of Armenia, was eliminated by the intervention of theParthiansand the pretender to the throneTigranes IV.This was a serious affront to Roman prestige.Augustus,no longer able to count on the cooperation ofTiberius(who had retired in voluntary retreat toRhodes) andAgrippanow dead for more than a decade, as well as being himself too old to undertake another trip to the East, decided to send his young nephewGaius Caesarto deal with the Armenian question, giving him proconsular powers superior to that of all provincial governors of the East. Also sent with him wasMarcus Lollius,who had gained experience in the East a few years earlier when he had to reorganize the newly created province ofGalatia.

Gaius CaesarreachedSyriain the beginning of the year 1 and there began his consulship. WhenPhraates V,king ofParthia,learned of the young prince's mission, he thought it would be more expedient to negotiate than to deal with the crisis harshly, risking a new war. He demanded, in exchange for his willingness to negotiate, the return of his four half-brothers who lived inRomeand posed a potential threat to his future security. Augustus, naturally, could only refuse to cede family members so important to the eastern cause. Instead, he enjoined him to leave Armenia.

Phraates Vrefused to leave the control of Armenia in the hands of the Romans, and continued to maintain his supervision of it over the new king,Tigranes IV,who, however, sent a number of ambassadors toRomewith gifts, acknowledging Augustus's power over his kingdom, and asking him to leave him on the throne. Augustus, satisfied with this recognition, accepted the gifts, but asked Tigranes to go to Gaius inSyriato negotiate his possible stay on the throne of Armenia.Tigranes III's behavior inducedPhraates Vto change his mind, forcing him to come to terms with Rome. He gave up his claims to see his half-brothers return, and declared himself ready to end all interference in Armenia.

That same year a pact was concluded between the Roman princeGaius Caesar,and the great king of theParthians,in neutral territory on an island in theEuphrates,again recognizing this river as the natural boundary between the two empires.[19]This meeting sanctioned the mutual recognition between Rome and Parthia, of independent states with equal rights of sovereignty. Before bidding farewell, the Parthian rulerPhraates Vinformed Gaius thatMarcus Lolliushad abused his role and had accepted rewards from powerful kings of eastern states. The accusation was true, and Gaius, after reviewing the evidence, removed Lollius from his retinue. A few days later Lollius died, probably by suicide, and he was replaced in the role of adviser to the prince byPublius Sulpicius Quirinius,mainly because of his military skills and diplomatic experience gained in his previous career.

Meanwhile,Tigranes IVhad been killed in the course of a war, possibly fomented by anti-Roman Armenian nobles opposed to submission to Rome. Tigranes' death was followed by the abdication ofErato,his half-sister and wife, and Gaius, in the name ofAugustus,gave the crown toAriobarzanes,already king ofMediasince 20 BC. The anti-Roman party, refusing to recognize Ariobarzane as the new king of Armenia, caused unrest everywhere, forcingGaius Caesarto intervene directly with thearmy.The Roman prince, shortly before attacking the fortress of Artagira (perhaps near Kagizman in theAras Rivervalley), was invited to an audience with the fort's commander, a certain Addon, who apparently wanted to reveal to him important details about theParthianking's wealth. This turned out, however, to be a trap, for upon his arrival Addon and his guards attempted to kill the Roman prince, who managed to survive the ambush although he was badly wounded.

The fort was, following these events, besieged and taken after a long resistance, and the revolt was quelled, but Gaius never recovered from his wound. He died two years later, in 4 A.D. inLycia.[20]This was the tragic end of years of negotiations, which led to a newmodus vivendibetween Parthia and Rome, and where the latter established its supremacy over the important Armenian state.

Consequences[edit]

Augustus' presence in the East immediately after theBattle of Actium,in 30-29 B.C. then from 22-19 B.C., as well asAgrippa's between 23-21 B.C. and again between 16-13 B.C., demonstrated the importance of this strategic area. It was necessary to reach amodus vivendiwith Parthia, the only power capable of creating problems for Rome along its eastern borders. In fact, both empires had more to lose from a defeat than they could realistically hope to gain from a victory. Throughout his long principate, Augustus concentrated his main military efforts in Europe.

Parthia effectively accepted that to the west of the Euphrates Rome organized the states as it pleased. The crucial point in the East, however, was thekingdom of Armenia,which, because of its geographical location, had been a subject of contention between Rome and Parthia for fifty years. The aim was to make Armenia a Roman client-state, with the enthronement of a king sympathetic to Rome, and if necessary imposed by force of arms.[21]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^R. Syme,L'Aristocrazia Augustea,Milano 1993, p. 104-105; A. Liberati – E. Silverio,Organizzazione militare: esercito,Museo della civiltà romana, vol. 5; R. Syme, "Some notes on the legions under Augustus", XXIII (1933), inJournal of Roman Studies,pp. 21-25.

- ^GJ.G.C.Anderson,Il problema partico e armeno: fattori costanti della situazione,Cambridge Ancient History, vol.VIII, inL'impero romano da Augusto agli Antonini,pp.111-142.

- ^E.Horst,Cesare,Milano 1982, p.269.

- ^Plutarch,Parallel Lives - Caesar, 58.

- ^Appian of Alexandria,Civil War, II.110.

- ^Cassius Dio,XLIII.47 and XLIII.49.

- ^Julio Rodriquez Gonzalez,Historia de las legiones romanas,p.722.

- ^R.Syme,Some notes on the legions under Augustus,Journal of Roman Studies 13, p.25 ss.

- ^Cassius Dio,Roman History, LIII, 25; LIV, 24.

- ^Flavius Josephus,Antiquities of the Jews XV, 10.

- ^D.Kennedy,L'Oriente,inIl mondo di Roma imperiale: la formazione,edited by J.Wacher, Bari 1989, p.306.

- ^D.Kennedy,L'Oriente,inIl mondo di Roma imperiale: la formazione,edited by J.Wacher, Bari 1989, pp.304-306.

- ^Roman Imperial Coinage,Augustus,I, 516.

- ^Roman Imperial Coinage,Augustus,I, 136; RSC -; cf. BMCRE 427 = BMCRR Rome 4453 (aureus); BN 1229-31.

- ^Cassius Dio,53.33.

- ^Strabo,Geography, XVII, 821;Cassius Dio,54.9, 4-5;Velleius PaterculusII, 94;Suetonius,The Twelve Caesars- Tiberius, 9.1.

- ^Cassius Dio,54.8, 1.Velleius Paterculus,History of Rome, II, 91.Livy,Ab Urbe condita, Epitome, 141.Suetonius,The Twelve Caesars,Augustus, 21; Tiberius, 9.

- ^Florus,Epitome of Roman History, 2.34.

- ^Cambridge University Press,Storia del mondo antico,L'impero romano da Augusto agli Antonini,vol. VIII, Milano 1975, pag. 135; Mazzarino, p. 81.

- ^Suetonius,Augustus,65.

- ^D.Kennedy,L'Oriente,inIl mondo di Roma imperiale: la formazione,edited by J.Wacher, Bari 1989, p.305.

Bibliography[edit]

- Augustus,Res gestae divi Augusti.

- Cassius Dio,Roman History,books LIII-LIX.

- Florus,Epitome of Roman History,II.

- Suetonius,The Twelve Caesars,books II and III.

- Tacitus,Annals,I-II.

- Velleius Paterculus,History of Rome,II.

- AAVV (1975).Cambridge Ancient History. L'impero romano da Augusto agli Antonini.Milan. pp. Vol. VIII.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - F.A.Arborio Mella,L'impero persiano da Ciro il Grande alla conquista araba,Milan 1980, Ed.Mursia.

- Grant, Michael (1984).Gli imperatori romani.Roma: Newton & Compton.

- E.Horst,Cesare,Milan 1982.

- D.Kennedy,L'Oriente,inIl mondo di Roma imperiale: la formazione,edited by J.Wacher, Bari 1989.

- Levi, Mario Attilio,Augusto e il suo tempo,Milan 1994.

- Santo Mazzarino(1976).L'Impero romano.Bari: Laterza. pp. Vol. I.

- Fergus Millar, The roman near east - 31 BC / AD 337, Harvard 1993.

- Scarre, Chris (1995).Chronicle of the Roman Emperors.London.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Scullard, Howard (1992).Storia del mondo romano.Milan: Rizzoli.

- Southern, Pat,Augustus,London-N.Y. 2001.

- Spinosa, Antonio (1996).Augusto. Il grande baro.Milan: Mondadori.ISBN9788804410416.

- Spinosa, Antonio (1991).Tiberio. L'imperatore che non amava Roma.Milan: Mondadori.

- Syme, Ronald(1992).L'aristocrazia augustea.Milan: Rizzoli.

- Syme, Ronald (2002).The Roman Revolution.Oxford.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)