Aboriginal Australians

TheAustralian Aboriginal flag.Together with theTorres Strait Islander flag,it was proclaimed

a flag of Australia in 1995. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 984,000 (2021)[1] 3.8% of Australia's population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 30.3% | |

| 5.5% | |

| 4.6% | |

| 3.9% | |

| 3.4% | |

| 2.5% | |

| 1.9% | |

| 0.9% | |

| Languages | |

| Several hundredAustralian Aboriginal languages,many no longer spoken,Australian English,Australian Aboriginal English,Kriol | |

| Religion | |

| MajorityChristian(mainlyAnglicanandCatholic),[2]minority no religious affiliation,[2]and small numbers of other religions, various local indigenous religions grounded inAustralian Aboriginal mythology | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Torres Strait Islanders,Aboriginal Tasmanians,Papuans | |

Aboriginal Australiansare the variousIndigenous peoplesof theAustralian mainlandand many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of theTorres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated toAustraliaat least 65,000 years ago, and over time formed as many as 500language-based groups.[3]In the past, Aboriginal people lived over large sections of thecontinental shelf.They were isolated on many of the smaller offshore islands andTasmaniawhen the land was inundated at the start of theHoloceneinter-glacial period,about 11,700 years ago. Despite this, Aboriginal people maintained extensive networks within the continent and certain groups maintained relationships withTorres Strait Islandersand theMakassarpeople of modern-day Indonesia.

Aboriginal Australians have a wide variety of cultural practices and beliefs that make up the oldest continuous cultures in the world.[4][5]At the time of European colonisation of Australia, the Aboriginal people consisted of complex cultural societies with more than 250languages[6]and varying degrees of technology and settlements.[vague]Languages (or dialects) and language-associated groups of people are connected with stretches of territory known as "Country", with which they have a profound spiritual connection. Over the millennia, Aboriginal people developed complex trade networks, inter-cultural relationships, law and religions.[3][7]

Contemporary Aboriginal beliefs are a complex mixture, varying by region and individual across the continent.[8]They are shaped by traditional beliefs, the disruption of colonisation, religions brought to the continent by Europeans, and contemporary issues.[8][9][10]Traditional cultural beliefs are passed down and shared throughdancing,stories,songlines,andartthat collectively weave anontologyof modern daily life and ancient creation known asDreaming.

Studies of Aboriginal groups' genetic makeup are ongoing, but evidence suggests that they have genetic inheritance from ancient Asian but not more modern peoples. They share some similarities withPapuans,but have been isolated fromSoutheast Asiafor a very long time. They have a broadly shared, complex genetic history, but only in the last 200 years were they defined by others as, and started to self-identify as, a single group.Aboriginal identityhas changed over time and place, with family lineage, self-identification, and community acceptance all of varying importance.

In the2021 census,Indigenous Australians comprised 3.8% of Australia's population.[1]Most Aboriginal people today speakEnglishand live in cities. Some may use Aboriginal phrases and words inAustralian Aboriginal English(which also has a tangible influence ofAboriginal languagesin thephonologyandgrammatical structure). Many but not all also speak the varioustraditional languagesof their clans and peoples. Aboriginal people, along with Torres Strait Islander people, have a number of severehealthand economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.

Origins

DNA studies have confirmed that "Aboriginal Australians are one of the oldest living populations in the world, certainly the oldest outside of Africa." Their ancestors left the African continent 75,000 years ago. They may have the oldest continuous culture on earth.[12]InArnhem Landin theNorthern Territory,oral histories comprising complex narratives have been passed down byYolngu peoplethrough hundreds of generations. TheAboriginal rock art,dated by modern techniques, shows that their culture has continued from ancient times.[13]

The ancestors of present-day Aboriginal Australian people migrated from Southeast Asia by sea during thePleistoceneepoch and lived over large sections of theAustralian continental shelfwhen thesea levelswere lower. At that time, Australia, Tasmania andNew Guineawere part of the same landmass, known asSahul.

As sea levels rose, the people on theAustralian mainlandand nearby islands became increasingly isolated, some on Tasmania and some of the smaller offshore islands when the land was inundated at the start of theHolocene,theinter-glacial periodthat started about 11,700 years ago.[14]Scholars of this ancient history believe that it would have been difficult for Aboriginal people to have originated purely from mainland Asia. Not enough people would have migrated to Australia and surrounding islands to fulfill the beginning of the size of the population seen in the 19th century. Scholars believe that most Aboriginal Australians originated from Southeast Asia. If this is the case, Aboriginal Australians were among the first in the world to have completed sea voyages.[15]

A 2017 paper inNatureevaluated artefacts inKakadu.Its authors concluded "Human occupation began around 65,000 years ago."[16]

A 2021 study by researchers at theAustralian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritagehas mapped the likely migration routes of the peoples as they moved across theAustralian continentto its southern reaches and what is nowTasmania,then part of the mainland. The modelling is based on data fromarchaeologists,anthropologists,ecologists,geneticists,climatologists,geomorphologists,andhydrologists.

It is intended to compare this data with theoral historiesof Aboriginal peoples, includingDreamingstories,Australian rock art,and linguistic features ofthe many Aboriginal languageswhich reveal how the peoples developed separately. The routes, dubbed "superhighways" by the authors, are similar to current highways andstock routesin Australia.

Lynette RussellofMonash Universitybelieves that the new model is a starting point for collaboration with Aboriginal people to help reveal their history. The new models suggest that the first people may have landed in theKimberley regionin what is nowWestern Australiaabout 60,000 years ago. They migrated across the continent within 6,000 years.[17][18]A 2018 study usingarchaeobotanydated evidence of continuous human habitation atKarnatukul(Serpent's Glen) in theCarnarvon Rangein theLittle Sandy Desertin WA from around 50,000 years ago.[19][note 1][20][21]

Genetics

Genetic studies have revealed that Aboriginal Australians largely descended from anEastern Eurasianpopulation wave during theInitial Upper Paleolithic.They are most closely related to otherOceanians,such asMelanesians.The Aboriginal Australians also show affinity to otherAustralasianpopulations, such asNegritos,as well as toEast Asian peoples.Phylogenetic data suggests that an early initial eastern lineage (ENA) trifurcated somewhere inSouth Asia,and gave rise to Australasians (Oceanians), Ancient Ancestral South Indian (AASI), Andamanese and the East/Southeast Asian lineage, including ancestors of theNative Americans.Papuans may have received approximately 2% of their geneflow from an earlier group (xOOA)[22]as well, next to additional archaic admixture in theSahulregion.[23][note 2][24]

Aboriginal people are genetically most similar to the indigenous populations ofPapua New Guinea,and more distantly related to groups from East Indonesia. They are more distinct from the indigenous populations ofBorneoandMalaysia,sharing drift with them than compared to the groups from Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. This indicates that populations in Australia were isolated for a long time from the rest of Southeast Asia. They remained untouched by migrations and population expansions into that area, which can be explained by theWallace line.[26]

In a 2001 study, blood samples were collected from someWarlpiri peoplein theNorthern Territoryto study their genetic makeup (which is not representative of all Aboriginal peoples in Australia). The study concluded that the Warlpiri are descended from ancient Asians whose DNA is still somewhat present in Southeastern Asian groups, although greatly diminished. The Warlpiri DNA lacks certain information found in modern Asian genomes, and carries information not found in other genomes. This reinforces the idea of ancient Aboriginal isolation.[26]

Genetic data extracted in 2011 by Morten Rasmussen et al., who took aDNA samplefrom an early-20th-century lock of an Aboriginal person's hair, found that the Aboriginal ancestors probably migrated throughSouth AsiaandMaritime Southeast Asia,into Australia, where they stayed. As a result, outside of Africa, the Aboriginal peoples have occupied the same territory continuously longer than any other human populations. These findings suggest that modern Aboriginal Australians are the direct descendants of the eastern wave, who left Africa up to 75,000 years ago.[27][28]This finding is compatible with earlier archaeological finds ofhuman remains near Lake Mungothat date to approximately 40,000 years ago.[citation needed]The idea of the "oldest continuous culture" is based on the Aboriginal peoples' geographical isolation, with little or no interaction with outside cultures before some contact withMakassanfishermen and Dutch explorers up to 500 years ago.[citation needed]

The Rasmussen study also found evidence that Aboriginal peoples carry some genes associated with theDenisovans(a species of human related to but distinct fromNeanderthals) of Asia; the study suggests that there is an increase inallelesharing between the Denisovan and Aboriginal Australian genomes, compared to other Eurasians or Africans. Examining DNA from a finger bone excavated inSiberia,researchers concluded that the Denisovans migrated fromSiberiato tropical parts of Asia and that they interbred with modern humans in Southeast Asia 44,000 years BP, before Australia separated from New Guinea approximately 11,700 years BP. They contributed DNA to Aboriginal Australians and to present-day New Guineans and an indigenous tribe in the Philippines known asMamanwa.This study confirms Aboriginal Australians as one of the oldest living populations in the world. They are possibly the oldest outside Africa, and they may have the oldest continuous culture on the planet.[29]

A 2016 study at theUniversity of Cambridgesuggests that it was about 50,000 years ago that these peoples reachedSahul(thesupercontinentconsisting of present-day Australia and its islands andNew Guinea). The sea levels rose and isolated Australia about 10,000 years ago, but Aboriginal Australians and Papuans diverged from each other genetically earlier, about 37,000 years BP, possibly because the remaining land bridge was impassable. This isolation makes the Aboriginal people the world's oldest culture. The study also found evidence of an unknownhominingroup, distantly related to Denisovans, with whom the Aboriginal and Papuan ancestors must have interbred, leaving a trace of about 4% in most Aboriginal Australians' genome. There is, however, increased genetic diversity among Aboriginal Australians based on geographical distribution.[30][31]

Carlhoff et al. 2021 analysed aHolocenehunter-gatherer sample ( "Leang Panninge" ) fromSouth Sulawesi,which shares high amounts of genetic drift with Aboriginal Australians and Papuans. This suggests that a population split from the common ancestor of Aboriginal Australians and Papuans. The sample also shows genetic affinity with East Asians and the Andamanese people of South Asia. The authors note that this hunter-gatherer sample can be modelled with ~50% Papuan-related ancestry and either with ~50% East Asian or Andamanese Onge ancestry, highlighting the deep split between Leang Panninge and Aboriginal/Papuans.[33][note 3]

Mallick et al. 2016 and Mark Lipson et al. 2017 study found the bifurcation of Eastern Eurasians and Western Eurasians dates to least 45,000 years ago, with indigenous Australians nested inside the Eastern Eurasian clade.[34][35]

Two genetic studies by Larena et al. 2021 found thatPhilippinesNegritopeople split from the common ancestor of Aboriginal Australians and Papuans before the latter two diverged from each other, but after their common ancestor diverged from the ancestor ofEast Asian peoples.[36][37][38]

Changes about 4,000 years ago

Thedingoreached Australia about 4,000 years ago. Near that time, there were changes in language (with thePama-Nyungan language familyspreading over most of the mainland), and instone tooltechnology. Smaller tools were used. Human contact has thus been inferred, and genetic data of two kinds have been proposed to support a gene flow from India to Australia: firstly, signs of South Asian components in Aboriginal Australian genomes, reported on the basis of genome-wideSNPdata; and secondly, the existence of aY chromosome(male) lineage, designatedhaplogroupC∗, with the most recent common ancestor about 5,000 years ago.[39]

The first type of evidence comes from a 2013 study by theMax Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropologyusing large-scalegenotypingdata from a pool of Aboriginal Australians, New Guineans, island Southeast Asians, and Indians. It found that the New Guinea andMamanwa(Philippines area) groups diverged from the Aboriginal about 36,000 years ago (there is supporting evidence that these populations are descended from migrants taking an early "southern route" out of Africa, before other groups in the area).[citation needed]Also the Indian and Australian populations mixed long before European contact, with this gene flow occurring during the Holocene (c.4,200 years ago).[40]The researchers had two theories for this: either some Indians had contact with people in Indonesia who eventually transferred those Indian genes to Aboriginal Australians, or a group of Indians migrated from India to Australia and intermingled with the locals directly.[41][42]

However, a 2016 study inCurrent Biologyby Anders Bergström et al. excluded the Y chromosome as providing evidence for recent gene flow from India into Australia. The study authors sequenced 13 Aboriginal Australian Y chromosomes using recent advances ingene sequencingtechnology. They investigated their divergence times from Y chromosomes in other continents, including comparing the haplogroup C chromosomes. They found a divergence time of about 54,100 years between the Sahul C chromosome and its closest relative C5, as well as about 54,300 years between haplogroups K*/M and their closest haplogroups R and Q. The deep divergence time of 50,000-plus years with the South Asian chromosome and "the fact that the Aboriginal Australian Cs share a more recent common ancestor with Papuan Cs" excludes any recent genetic contact.[39]

The 2016 study's authors concluded that, although this does not disprove the presence of any Holocene gene flow or non-genetic influences from South Asia at that time, and the appearance of the dingo does provide strong evidence for external contacts, the evidence overall is consistent with a complete lack of gene flow, and points to indigenous origins for the technological and linguistic changes. They attributed the disparity between their results and previous findings to improvements in technology; none of the other studies had utilised complete Y chromosome sequencing, which has the highest precision. For example, use of a ten Y STRs method has been shown to massively underestimate divergence times. Gene flow across the island-dotted 150-kilometre-wide (93 mi) Torres Strait, is both geographically plausible and demonstrated by the data, although at this point it could not be determined from this study when within the last 10,000 years it may have occurred—newer analytical techniques have the potential to address such questions.[39]

Bergstrom's 2018 doctoral thesis looking at the population of Sahul suggests that other than relatively recent admixture, the populations of the region appear to have been genetically independent from the rest of the world since their divergence about 50,000 years ago. He writes "There is no evidence for South Asian gene flow to Australia.... Despite Sahul being a single connected landmass until [8,000 years ago], different groups across Australia are nearly equally related to Papuans, and vice versa, and the two appear to have separated genetically already [about 30,000 years ago]."[43]

Environmental adaptations

Aboriginal Australians possess inherited abilities to adapt to a wide range of environmental temperatures in various ways. A study in 1958 comparing cold adaptation in the desert-dwellingPitjantjatjara peoplecompared with a group of European people showed that the cooling adaptation of the Aboriginal group differed from that of the white people, and that they were able to sleep more soundly through a cold desert night.[44]A 2014Cambridge Universitystudy found that a beneficial mutation in two genes which regulatethyroxine,a hormone involved in regulating bodymetabolism,helps to regulate body temperature in response to fever. The effect of this is that the desert people are able to have a higher body temperature without accelerating the activity of the whole of the body, which can be especially detrimental in childhood diseases. This helps protect people to survive the side-effects of infection.[45][46]

Location and demographics

Aboriginal people have lived for tens of thousands of years on thecontinent of Australia,through its various changes in landmass. The area withinAustralia's borders today includes the islands ofTasmania,K'gari (previously Fraser Island),Hinchinbrook Island,[47]theTiwi Islands,Kangaroo IslandandGroote Eylandt.Indigenous people of the Torres Strait Islands, however, are not Aboriginal.[48][49][50][51]

| Census | Number of persons | Intercensal change (number) | Intercensal change (percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 455,028 | 45,025 | 11.0 |

| 2011 | 548,368 | 93,340 | 20.5 |

| 2016 | 649,171 | 100,803 | 18.4 |

| 2021 | 812,728 | 163,557 | 25.2 |

In the2021 census,people who self-identified on the census form as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin totalled 812,728 out of a total of 25,422,788 Australians, equating to 3.2% of Australia's population[53]and an increase of 163,557 people, or 25.2%, since the previous census in 2016.[52]Reasons for the increase were broadly as follows:

- Demographicfactors – births, deaths and migration[note 4]– accounted for 43.5% of the increase (71,086 people). In turn, 76.2% of that increase was attributed to people aged 0–19 years in 2021, broken down as 52.5% for 0–4 year olds (births since 2016) and 23.7% for 5–19 year olds.[52]

- Non-demographic factors, which are complex to quantify, include persons identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in a particular census, and changes in census coverage and response – such as persons completing a census form in 2021 but not in 2016. These factors accounted for 56.5% of the increase in the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander population (92,471 people). The increase was higher than observed between 2011–2016 (39.0%) and 2006–2011 (38.7%).[52]

Languages

Most Aboriginal people speak English,[54]with Aboriginal phrases and words being added to createAustralian Aboriginal English(which also has a tangible influence ofAboriginal languagesin thephonologyandgrammatical structure).[55]Some Aboriginal people, especially those living in remote areas, are multi-lingual.[54]Many of the original 250–400 Aboriginal languages (more than 250 languages and about 800 dialectal varieties on the continent) are endangered or extinct,[56]although some efforts are being made atlanguage revivalfor some. As of 2016, only 13 traditional Indigenous languages were still being acquired by children,[57]and about another 100 spoken by older generations only.[56]

Groups and sub-groups

Dispersing across the Australian continent over time, the ancient people expanded and differentiated into distinct groups, each with its own language and culture.[58]More than 400 distinct Australian Aboriginalpeopleshave been identified, distinguished by names designating theirancestrallanguages, dialects, or distinctive speech patterns.[59]According to notedanthropologist,archaeologistand sociologistHarry Lourandos,historically, these groups lived in three main cultural areas, the Northern, Southern and Central cultural areas. The Northern and Southern areas, having richer natural marine and woodland resources, were more densely populated than the Central area.[58]

Geographically-based names

There are various other names fromAustralian Aboriginal languagescommonly used to identify groups based ongeography,known asdemonyms,including:

- Ananguin northernSouth Australia,and neighbouring parts ofWestern AustraliaandNorthern Territory

- Goorie (variant pronunciation and spelling of Koori) in South East Queensland and some parts of northern New South Wales

- Koori(or Koorie) in New South Wales andVictoria(Aboriginal Victorians)

- Murriin Central and Northern Queensland, sometimes referring to all Aboriginal Queenslanders

- Nungain southern South Australia

- Noongarin southern Western Australia

- Palawah(or Pallawah) inTasmania

- TiwionTiwi IslandsoffArnhem Land(NT)

A few examples of sub-groups

Other group names are based on thelanguage group or specific dialect spoken.These also coincide with geographical regions of varying sizes. A few examples are:

- AnindilyakwaonGroote Eylandt(off Arnhem Land), NT

- Arrerntein central Australia[15]

- Bininjin Western Arnhem Land (NT)[60]

- Gunggariin south-west Queensland[61]

- Muruwaripeople in New South Wales

- Luritja(Kukatja), an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Ngunnawalin theAustralian Capital Territoryand surrounding areas of New South Wales

- Pitjantjatjara,an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Wangaiin theWestern Australian Goldfields

- Warlpiri(Yapa) in western central Northern Territory

- Yamatjiin central Western Australia

- Yolnguin eastern Arnhem Land (NT)

Difficulties defining groups

However, these lists are neither exhaustive nor definitive, and there are overlaps. Different approaches have been taken by non-Aboriginal scholars in trying to understand and define Aboriginal culture and societies, some focusing on the micro-level (tribe, clan, etc.), and others on shared languages and cultural practices spread over large regions defined by ecological factors.Anthropologistshave encountered many difficulties in trying to define what constitutes an Aboriginal people/community/group/tribe, let alone naming them. Knowledge of pre-colonial Aboriginal cultures and societal groupings is still largely dependent on the observers' interpretations, which were filtered through colonial ways of viewing societies.[62]

Some Aboriginal peoples identify as one of severalsaltwater, freshwater, rainforest or desert peoples.

Aboriginal identity

Terminology

The termAboriginal Australiansincludes many distinct peoples who have developed across Australia for over 50,000 years.[16][63]These peoples have a broadly shared, though complex, genetic history,[64][42]but it is only in the last two hundred years that they have been defined and started to self-identify as a single group, socio-politically.[65][66]While some preferred the termAboriginetoAboriginalin the past, as the latter was seen to have more directly discriminatory legal origins,[65]use of the termAboriginehas declined in recent decades, as many consider the term an offensive and racist hangover from Australia's colonial era.[67][68]

The definition of the termAboriginalhas changed over time and place, with the importance of family lineage, self-identification and community acceptance all being of varying importance.[69][70][71]

The termIndigenous Australiansrefers to Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the term is conventionally only used when both groups are included in the topic being addressed, or by self-identification by a person as Indigenous. (Torres Strait Islanders are ethnically and culturally distinct,[72]despite extensive cultural exchange with some of the Aboriginal groups,[73]and the Torres Strait Islands are mostly part of Queensland but have aseparate governmental status.) Some Aboriginal people object to being labelledIndigenous,as an artificial and denialist term.[66]

Culture and beliefs

Australian Indigenous people have beliefs unique to each mob (tribe) and have a strong connection to the land.[4][5]Contemporary Indigenous Australian beliefs are a complex mixture, varying by region and individual across the continent.[8]They are shaped by traditional beliefs, the disruption of colonisation, religions brought to the continent by Europeans, and contemporary issues.[8][9][10]Traditional cultural beliefs are passed down and shared bydancing,stories,songlinesandart—especiallyPapunya Tula(dot painting)—collectively telling the story of creation known asThe Dreamtime.[74][4]Additionally, traditional healers were also custodians of important Dreaming stories as well as their medical roles (for example theNgangkariin theWestern desert).[75]Some core structures and themes are shared across the continent with details and additional elements varying between language and cultural groups.[8]For example, in The Dreamtime of most regions, a spirit creates the earth then tells the humans to treat the animals and the earth in a way which is respectful to land. InNorthern Territorythis is commonly said to be a huge snake or snakes that weaved its way through the earth and sky making the mountains and oceans. But in other places the spirits who created the world are known aswandjinarain and water spirits. Majorancestralspirits include theRainbow Serpent,Baiame,DirawongandBunjil.Similarly, the Arrernte people of central Australia believed that humanity originated from great superhuman ancestors who brought the sun, wind and rain as a result of breaking through the surface of the Earth when waking from their slumber.[15]

Health and economic deprivations

Taken as a whole, Aboriginal Australians, along with Torres Strait Islander people, have a number of health and economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.[76][77]

Due to the aforementioned disadvantage, Aboriginal Australian communities experience a higher rate of suicide, as compared to non-indigenous communities. These issues stem from a variety of different causes unique to indigenous communities, such as historical trauma,[78]socioeconomic disadvantage, and decreased access to education and health care.[79]Also, this problem largely affects indigenous youth, as many indigenous youth may feel disconnected from their culture.[80]

To combat the increased suicide rate, many researchers have suggested that the inclusion of more cultural aspects into suicide prevention programs would help to combat mental health issues within the community. Past studies have found that many indigenous leaders and community members, do in fact, want more culturally-aware health care programs.[81]Similarly, culturally-relative programs targeting indigenous youth have actively challenged suicide ideation among younger indigenous populations, with many social and emotional wellbeing programs using cultural information to provide coping mechanisms and improving mental health.[82][83]

Viability of remote communities

Theoutstation movementof the 1970s and 1980s, when Aboriginal people moved to tiny remote settlements on traditional land, brought health benefits,[84][85]but funding them proved expensive, training and employment opportunities were not provided in many cases, and support from governments dwindled in the 2000s, particularly in the era of theHoward government.[86][87][88]

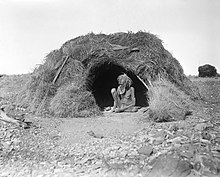

Indigenous communities in remote Australia are often small, isolated towns with basic facilities, ontraditionally owned land.These communities have between 20 and 300 inhabitants and are often closed to outsiders for cultural reasons. The long-term viability and resilience of Aboriginal communities in desert areas has been discussed by scholars and policy-makers. A 2007 report by theCSIROstressed the importance of taking a demand-driven approach to services in desert settlements, and concluded that "if top-down solutions continue to be imposed without appreciating the fundamental drivers of settlement in desert regions, then those solutions will continue to be partial, and ineffective in the long term."[89]

See also

- List of Indigenous Australian politicians

- List of Indigenous Australians in politics and public service

- Aboriginal Centre for the Performing Arts (ACPA)

- Aboriginal cultures of Western Australia

- Aboriginal South Australians

- Australian Aboriginal culture

- Australian Aboriginal kinship

- Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology

- Climate change in Australia

- Indigenous Australian art

- Indigenous Australian music

- First Nations Media Australia

- Indigenous land rights in Australia

- List of Aboriginal missions in New South Wales

- List of Indigenous Australian firsts

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Lists of Indigenous Australians

- National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award

- Native title in Australia

- Stolen Generations

- Supply Nation

Notes

- ^"The re-excavation of Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen) has provided evidence for the human occupation of the Australian Western Desert to before 47,830 cal. BP (modelled median age). This new sequence is 20,000 years older than the previous known age for occupation at this site."

- ^Genetics and material culture support repeated expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a population hub out of Africa, Vallini et al. 2022 (April 4, 2022): "Taken together with a lower bound of the final settlement of Sahul at 37 ka (the date of the deepest population splits estimated by Malaspinas et al. 2016), it is reasonable to describe Papuans as either an almost even mixture between East Asians and a lineage basal to West and East Asians occurred sometimes between 45 and 38 ka, or as a sister lineage of East Asians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution. We here chose to parsimoniously describe Papuans as a simple sister group of Tianyuan, cautioning that this may be just one out of six equifinal possibilities."

- ^TheqpGraphanalysis confirmed this branching pattern, with the Leang Panninge individual branching off from the Near Oceanian clade after the Denisovan gene flow. The most supported topology indicates around 50% of a basal East Asian component contributing to the Leang Panninge genome (fig. 3c, supplementary figs. 7–11).

- ^Population change due to overseas migration continued to account for less than 2 per cent of the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander population.

References

- ^ab"Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians".Australian Bureau of Statistics.June 2023.

- ^ab"4713.0 – Population Characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians".Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4 May 2010.

- ^abBerndt, Ronald M.; Tonkinson, Robert (2023)."Traditional sociocultural patterns".Britannica.Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.Retrieved19 July2023.

- ^abc"Behind the dots of Aboriginal Art".Retrieved25 November2021.

- ^abTonkinson, Robert (2011),"Landscape, Transformations, and Immutability in an Aboriginal Australian Culture",Cultural Memories,Knowledge and Space, vol. 4, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 329–345,doi:10.1007/978-90-481-8945-8_18,ISBN978-90-481-8944-1,retrieved21 May2021

- ^"Community, identity, wellbeing: The report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey".AIATSIS.2014. Archived fromthe originalon 24 April 2015.Retrieved18 May2015.

- ^Berndt, Ronald M.; Tonkinson, Robert (2023)."Australian Aboriginal peoples".Britannica.Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.Retrieved19 July2023.

- ^abcdeCox, James Leland (2016).Religion and non-religion among Australian Aboriginal peoples.London: Routledge.ISBN978-1-4724-4383-0.OCLC951371681.

- ^abHarvey, Arlene; Russell-Mundine, Gabrielle (18 August 2019)."Decolonising the curriculum: using graduate qualities to embed Indigenous knowledges at the academic cultural interface".Teaching in Higher Education.24(6): 789–808.doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1508131.ISSN1356-2517.S2CID149824646.

- ^abFraser, Jenny (25 January 2012)."The digital dreamtime: A shining light in the culture war".Te Kaharoa.5(1).doi:10.24135/tekaharoa.v5i1.77.ISSN1178-6035.

- ^Graves, Randin (2 June 2017)."Yolngu are People 2: They're not Clip Art".Yidaki History.Retrieved30 August2020.

- ^"DNA confirms Aboriginal culture one of Earth's oldest".Australian Geographic.23 September 2011.Retrieved21 May2024.

- ^"Discover the oldest continuous living culture on Earth".The Telegraph.22 December 2023.Retrieved21 May2024.

- ^Rebe Taylor(2002).Unearthed: The Aboriginal Tasmanians of Kangaroo Island.Kent Town: Wakefield Press.ISBN978-1-86254-552-6.

- ^abcRead, Peter; Broome, Richard (1982)."Aboriginal Australians".Labour History(43): 125–126.doi:10.2307/27508560.ISSN0023-6942.JSTOR27508560.

- ^abClarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; et al. (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago".Nature.547(7663): 306–310.Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C.doi:10.1038/nature22968.hdl:2440/107043.ISSN0028-0836.PMID28726833.S2CID205257212.

- ^Morse, Dana (30 April 2021)."Researchers demystify the secrets of ancient Aboriginal migration across Australia".ABC News.Australian Broadcasting Corporation.Retrieved7 May2021.

- ^Crabtree, S.A.; White, D.A.; et al. (29 April 2021)."Landscape rules predict optimal superhighways for the first peopling of Sahul".Nature Human Behaviour.5(10): 1303–1313.doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01106-8.PMID33927367.S2CID233458467.Retrieved7 May2021.

- ^McDonald, Josephine; Reynen, Wendy; Petchey, Fiona; Ditchfield, Kane; Byrne, Chae; Vannieuwenhuyse, Dorcas; Leopold, Matthias; Veth, Peter (September 2018)."Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen): A new chronology for the oldest site in Australia's Western Desert".PLOS ONE.13(9): e0202511.Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1302511M.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0202511.PMC6145509.PMID30231025– viaResearchGate.

- ^McDonald, Jo; Veth, Peter (2008)."Rock- art: Pigment dates provide new perspectives on the role of art in the Australian arid zone".Australian Aboriginal Studies(2008/1): 4–21 – viaResearchGate.

- ^McDonald, Jo (2 July 2020)."Serpents Glen (Karnatukul): New Histories for Deep time Attachment to Country in Australia's Western Desert".Bulletin of the History of Archaeology.30(1).doi:10.5334/bha-624.ISSN2047-6930.S2CID225577563.

- ^"Almost all living people outside of Africa trace back to a single migration more than 50,000 years ago".science.org.Retrieved19 August2022.

- ^Yang, Melinda A. (6 January 2022)."A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia".Human Population Genetics and Genomics.2(1): 1–32.doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001.ISSN2770-5005.

- ^Taufik, Leonard; Teixeira, João C.; Llamas, Bastien; Sudoyo, Herawati; Tobler, Raymond; Purnomo, Gludhug A. (16 December 2022)."Human Genetic Research in Wallacea and Sahul: Recent Findings and Future Prospects".Genes.13(12): 2373.doi:10.3390/genes13122373.ISSN2073-4425.PMC9778601.PMID36553640.

- ^Aghakhanian, Farhang (14 April 2015)."Unravelling the Genetic History of Negritos and Indigenous Populations of Southeast Asia".Genome Biology and Evolution.7(5): 1206–1215.doi:10.1093/gbe/evv065.PMC4453060.PMID25877615.Retrieved8 May2022.

- ^abHuoponen, Kirsi; Schurr, Theodore G.; et al. (1 September 2001). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in an Aboriginal Australian population: evidence for genetic isolation and regional differentiation".Human Immunology.62(9): 954–969.doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00294-4.PMID11543898.

- ^Rasmussen, Morten; Guo, Xiaosen; et al. (7 October 2011)."An Aboriginal Australia Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia".Science.334(6052). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 94–98.Bibcode:2011Sci...334...94R.doi:10.1126/science.1211177.PMC3991479.PMID21940856.

- ^Callaway, Ewen (2011)."First Aboriginal genome sequenced".Nature.doi:10.1038/news.2011.551.ISSN1476-4687.Retrieved16 January2016.

- ^"DNA confirms Aboriginal culture is one of the Earth's oldest".Australian Geographic. 23 September 2011.

- ^Klein, Christopher (23 September 2016)."DNA Study Finds Aboriginal Australians World's Oldest Civilization".History.A&E Television Networks.Retrieved13 March2020.

Updated Aug 22, 2018

- ^Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Westaway, Michael C.; Muller, Craig; Sousa, Vitor C.; Lao, Oscar; Alves, Isabel; Bergström, Anders; et al. (13 October 2016). "A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia".Nature.538(7624): 207–214.Bibcode:2016Natur.538..207M.doi:10.1038/nature18299.hdl:10754/622366.ISSN0028-0836.PMID27654914.

- ^Gomes, Sibylle M.; Bodner, Martin; Souto, Luis; Zimmermann, Bettina; Huber, Gabriela; Strobl, Christina; Röck, Alexander W.; Achilli, Alessandro; Olivieri, Anna; Torroni, Antonio; Côrte-Real, Francisco (14 February 2015)."Human settlement history between Sunda and Sahul: a focus on East Timor (Timor-Leste) and the Pleistocenic mtDNA diversity".BMC Genomics.16(1): 70.doi:10.1186/s12864-014-1201-x.ISSN1471-2164.PMC4342813.PMID25757516.

- ^Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (2021)."Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea".Nature.596(7873): 543–547.Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C.doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6.ISSN0028-0836.PMC8387238.PMID34433944.

- ^Mallick, Swapan; Li, Heng; Lipson, Mark; Mathieson, Iain; Patterson, Nick; Reich, David (13 October 2016)."The Simons Genome Diversity Project: 300 genomes from 142 diverse populations".Nature.538(7624): 201–206.Bibcode:2016Natur.538..201M.doi:10.1038/nature18964.ISSN0028-0836.PMC5161557.PMID27654912.

- ^Lipson, Mark; Reich, David (April 2017)."A Working Model of the Deep Relationships of Diverse Modern Human Genetic Lineages Outside of Africa".Molecular Biology and Evolution.34(4): 889–902.doi:10.1093/molbev/msw293.PMC5400393.PMID28074030.

- ^Larena, M (March 2021).""Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13): e2026132118 ".118(13): e2026132118.doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118.PMC8020671.PMID33753512.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^Larena M, McKenna J, Sanchez-Quinto F, Bernhardsson C, Ebeo C, Reyes R, et al. (October 2021)."Philippine Ayta possess the highest level of Denisovan ancestry in the world".Current Biology.31(19): 4219–4230.e10.Bibcode:2021CBio...31E4219L.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.07.022.PMC8596304.PMID34388371.

- ^Lipson, Mark; Reich, David (2017)."A Working Model of the Deep Relationships of Diverse Modern Human Genetic Lineages Outside of Africa".Molecular Biology and Evolution.34(4): 889–902.doi:10.1093/molbev/msw293.ISSN0737-4038.PMC5400393.PMID28074030.

- ^abcBergström, Anders; Nagle, Nano; Chen, Yuan; McCarthy, Shane; Pollard, Martin O.; Ayub, Qasim; Wilcox, Stephen; Wilcox, Leah; van Oorschot, Roland A. H.; McAllister, Peter; Williams, Lesley; Xue, Yali; Mitchell, R. John; Tyler-Smith, Chris (21 March 2016)."Deep Roots for Aboriginal Australian Y Chromosomes".Current Biology.26(6): 809–813.Bibcode:2016CBio...26..809B.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.028.PMC4819516.PMID26923783.

- ^Pugach, Irina; Delfin, Frederick; Gunnarsdóttir, Ellen; Kayser, Manfred; Stoneking, Mark (29 January 2013)."Genome-wide data substantiate Holocene gene flow from India to Australia".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(5): 1803–1808.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1803P.doi:10.1073/pnas.1211927110.PMC3562786.PMID23319617.

- ^Sanyal, Sanjeev (2016).The ocean of churn: how the Indian Ocean shaped human history.Gurgaon, Haryana, India: Penguin UK. p. 59.ISBN9789386057617.OCLC990782127.

- ^abMacDonald, Anna (15 January 2013)."Research shows ancient Indian migration to Australia".ABC News.

- ^Bergström, Anders (20 July 2018).Genomic insights into the human population history of Australia and New Guinea(PhD thesis). University of Cambridge.doi:10.17863/CAM.20837.

- ^Scholander, P. F.; Hammel, H. T.; et al. (1 September 1958). "Cold Adaptation in Australian Aborigines".Journal of Applied Physiology.13(2): 211–218.doi:10.1152/jappl.1958.13.2.211.PMID13575330.

- ^Caitlyn Gribbin (29 January 2014)."Genetic mutation helps Aboriginal people survive tough climate, research finds"(text and audio).ABC News.

- ^Qi, Xiaoqiang; Chan, Wee Lee; Read, Randy J.; Zhou, Aiwu; Carrell, Robin W. (22 March 2014)."Temperature-responsive release of thyroxine and its environmental adaptation in Australians".Proceedings of the Royal Society B.281(1779): 20132747.doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2747.PMC3924073.PMID24478298.

- ^"Preferences in terminology when referring to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples"(PDF).Gulanga Good Practice Guides. ACT Council of Social Service Inc. December 2016.Retrieved16 December2019.

- ^"Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976".Federal Register of Legislation.No. 191, 1976: Compilation No. 41. Australian Government. 4 April 2019.Retrieved12 December2019.

s 3: Aboriginal means a person who is a member of the Aboriginal race of Australia....12AAA. Additional grant to Tiwi Land Trust...

- ^"Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005".Federal Register of Legislation.No. 150, 1989: Compilation No. 54. Australian Government. 4 April 2019.Retrieved12 December2019.s 4: "Aboriginal personmeans a person of the Aboriginal race of Australia. "

- ^Venbrux, Eric (1995).A death in the Tiwi islands: conflict, ritual, and social life in an Australian aboriginal community.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-47351-4.

- ^Rademaker, Laura (7 February 2018)."Tiwi Christianity: Aboriginal histories, Catholic mission and a surprising conversion".ABC Religion and Ethics.Australian Broadcasting Corporation.Retrieved12 December2019.

- ^abcd"Understanding change in counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: Census".Australian Bureau of Statistics.4 April 2023.Retrieved25 July2023.

- ^"Australia: 2021 census all persons QuickStats".Australian Bureau of Statistics.Retrieved25 July2023.

- ^ab"2076.0: Characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2016: Main language spoken at home and English proficiency".Australian Bureau of Statistics.14 March 2019.Retrieved3 July2020.

- ^"What is Aboriginal English like, and how would you recognise it?".ABED.12 March 2019.Retrieved3 July2020.

- ^ab"Indigenous Australian Languages".Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.3 June 2015.Retrieved3 July2020.

- ^Simpson, Jane (20 January 2019)."The state of Australia's Indigenous languages – and how we can help people speak them more often".The Conversation.Retrieved3 July2020.

- ^abLourandos, Harry.New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory,Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom (1997)ISBN0-521-35946-5

- ^Horton, David (1994)The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History, Society, and Culture,Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.ISBN0-85575-234-3.

- ^Garde, Murray."bininj".Bininj Kunwok Dictionary.Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre.Retrieved20 June2019.

- ^"General Reference".Life and Times of the Gunggari People, QLD (Pathfinder).Retrieved29 November2016.

- ^Monaghan, Paul (2017)."Chapter 1: Structures of Aboriginal life at the time of colonisation".In Brock, Peggy; Gara, Tom (eds.).Colonialism and its Aftermath: A history of Aboriginal South Australia.Wakefield Press.pp. 10, 12.ISBN9781743054994.

- ^Walsh, Michael; Yallop, Colin (1993).Language and Culture in Aboriginal Australia.Aboriginal Studies Press. pp. 191–193.ISBN9780855752415.

- ^Edwards, W. H. (2004).An Introduction to Aboriginal Societies(2nd ed.). Social Science Press. p. 2.ISBN978-1-876633-89-9.

- ^abFesl, Eve D.(1986)."'Aborigine' and 'Aboriginal'".Aboriginal Law Bulletin.(1986) 1(20)Aboriginal Law Bulletin10 Accessed 19 August 2011

- ^ab"Don't call me indigenous: Lowitja".The Age.Melbourne. Australian Associated Press. 1 May 2008.Retrieved12 April2010.

- ^Solonec, Tammy (9 August 2015)."Why saying 'Aborigine' isn't OK: 8 facts about Indigenous people in Australia".Amnesty.org.Amnesty International.Retrieved5 August2020.

- ^"Why do media organisations like News Corp, Reuters and The New York Times still use words like 'Aborigines'?".NITV.5 March 2018.Retrieved19 July2021.

- ^"Aboriginality and Identity: Perspectives, Practices and Policies"(PDF).New South Wales AECG Inc. 2011. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 October 2016.Retrieved1 August2016.

- ^Blandy, Sarah; Sibley, David (2010). "Law, boundaries and the production of space".Social & Legal Studies.19(3): 275–284.doi:10.1177/0964663910372178.S2CID145479418."Aboriginal Australians are a legally defined group" (p. 280).

- ^Malbon, Justin (2003). "The Extinguishment of Native Title—The Australian Aborigines as Slaves and Citizens".Griffith Law Review.12(2): 310–335.doi:10.1080/10383441.2003.10854523.S2CID147150152.Aboriginal Australians have been "assigned a separate legally defined status" (p 322).

- ^"About the Torres Strait".Torres Strait Shire Council.Retrieved21 October2019.

- ^"Australia Now – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples".8 October 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 8 October 2006.Retrieved8 February2019.

- ^Green, Jennifer (2012)."The Altyerre Story-'Suffering Badly by Translation': The Altyerre Story".The Australian Journal of Anthropology.23(2): 158–178.doi:10.1111/j.1757-6547.2012.00179.x.

- ^Traditional healers of central Australia: Ngangkari.Broome, Western Australia: Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjar Yankunytjatjara Women's Council Aboriginal Corporation, Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation. 2013.ISBN978-1-921248-82-5.OCLC819819283.

- ^"4704.0 - The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Oct 2010".Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Government.17 February 2011.Retrieved3 February2020.

- ^"Indigenous Socioeconomics Indicators, Benefits and Expenditure".Parliament of Australia.7 August 2001.Retrieved3 February2020.

- ^Elliott-Farrelly, Terri (January 2004)."Australian Aboriginal suicide: The need for an Aboriginal suicidology?".Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health.3(3): 138–145.doi:10.5172/jamh.3.3.138.ISSN1446-7984.S2CID71578621.

- ^Marrone, Sonia (July 2007)."Understanding barriers to health care: a review of disparities in health care services among indigenous populations".International Journal of Circumpolar Health.66(3): 188–198.doi:10.3402/ijch.v66i3.18254.ISSN2242-3982.PMID17655060.S2CID1720215.

- ^Isaacs, Anton; Sutton, Keith (16 June 2016)."An Aboriginal youth suicide prevention project in rural Victoria".Advances in Mental Health.14(2): 118–125.doi:10.1080/18387357.2016.1198232.ISSN1838-7357.S2CID77905930.

- ^Ridani, Rebecca; Shand, Fiona L.; Christensen, Helen; McKay, Kathryn; Tighe, Joe; Burns, Jane; Hunter, Ernest (16 September 2014)."Suicide Prevention in Australian Aboriginal Communities: A Review of Past and Present Programs".Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior.45(1): 111–140.doi:10.1111/sltb.12121.ISSN0363-0234.PMID25227155.

- ^Skerrett, Delaney Michael; Gibson, Mandy; Darwin, Leilani; Lewis, Suzie; Rallah, Rahm; De Leo, Diego (30 March 2017)."Closing the Gap in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth Suicide: A Social-Emotional Wellbeing Service Innovation Project".Australian Psychologist.53(1): 13–22.doi:10.1111/ap.12277.ISSN0005-0067.S2CID151609217.

- ^Murrup-Stewart, Cammi; Searle, Amy K.; Jobson, Laura; Adams, Karen (16 November 2018)."Aboriginal perceptions of social and emotional wellbeing programs: A systematic review of literature assessing social and emotional wellbeing programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians perspectives".Australian Psychologist.54(3): 171–186.doi:10.1111/ap.12367.ISSN0005-0067.S2CID150362243.

- ^Morice, Rodney D. (1976). "Woman Dancing Dreaming: Psychosocial Benefits of the Aboriginal Outstation Movement".Medical Journal of Australia.2(25–26). AMPCo: 939–942.doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1976.tb115531.x.ISSN0025-729X.PMID1035404.S2CID28327004.

- ^Ganesharajah, Cynthia (April 2009).Indigenous Health and Wellbeing: The Importance of Country(PDF).Native Title Research Report Report No. 1/2009.AIATSIS.Native Title Research Unit.ISBN9780855756697.Retrieved17 August2020.AIATSIS summaryArchived4 May 2020 at theWayback Machine

- ^Myers, Fred; Peterson, Nicolas (January 2016)."1. The origins and history of outstations as Aboriginal life projects".In Peterson, Nicolas; Myers, Fred (eds.).Experiments in self-determination: Histories of the outstation movement in Australia.Monographs in Anthropology. ANU Press. p. 2.ISBN9781925022902.Retrieved17 August2020.

- ^Palmer, Kingsley (January 2016)."10. Homelands as outstations of public policy".In Peterson, Nicolas; Myers, Fred (eds.).Experiments in self-determination: Histories of the outstation movement in Australia.Monographs in Anthropology. ANU Press.ISBN9781925022902.Retrieved17 August2020.

- ^Altman, Jon (25 May 2009)."No movement on the outstations".The Sydney Morning Herald.Retrieved16 August2020.

- ^Smith, M. S.; Moran, M.; Seemann, K. (2008). "The 'viability' and resilience of communities and settlements in desert Australia".The Rangeland Journal.30:123.doi:10.1071/RJ07048.

![]() This article incorporatestextby Anders Bergström et al. available under theCC BY 4.0license.

This article incorporatestextby Anders Bergström et al. available under theCC BY 4.0license.

Further reading

- "Start exploring Australian Aboriginal culture".Creative Spirits.24 December 2018.

- "Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies".AIATSIS.

- "Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies".AIATSIS.

- "Aboriginal Art of Australia: Understanding its History".ARTARK.Retrieved28 August2023.

External links

Media related toAboriginal Australiansat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toAboriginal Australiansat Wikimedia Commons