Autosome

Anautosomeis anychromosomethat is not asex chromosome.[1]The members of an autosome pair in adiploidcell have the samemorphology,unlike those inallosomal(sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. TheDNAin autosomes is collectively known asatDNAorauDNA.[2]

For example,humanshavea diploid genomethat usually contains 22 pairs of autosomes and oneallosomepair (46 chromosomes total). The autosome pairs are labeled with numbers (1–22 in humans) roughly in order of their sizes in base pairs, while allosomes are labelled with their letters.[3]By contrast, the allosome pair consists of twoX chromosomesin females or one X and oneY chromosomein males. Unusual combinations ofXYY,XXY,XXX,XXXX,XXXXXorXXYY,amongother Salome combinations,[clarification needed]are known to occur and usually cause developmental abnormalities.

Autosomes still contain sexual determinationgeneseven though they are not sex chromosomes. For example, theSRYgene on the Y chromosome encodes the transcription factorTDFand is vital for male sex determination during development. TDF functions by activating theSOX9gene onchromosome 17,so mutations of theSOX9gene can cause humans with an ordinary Y chromosome to develop as females.[4]

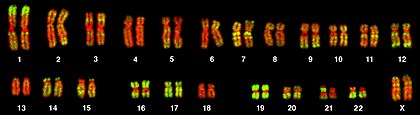

All human autosomes have been identified and mapped by extracting the chromosomes from a cell arrested inmetaphaseorprometaphaseand then staining them with a type of dye (most commonly,Giemsa).[5]These chromosomes are typically viewed askaryogramsfor easy comparison. Clinical geneticists can compare the karyogram of an individual to a reference karyogram to discover the cytogenetic basis of certainphenotypes.For example, the karyogram of someone withPatau Syndromewould show that they possess three copies ofchromosome 13.Karyograms and staining techniques can only detect large-scale disruptions to chromosomes—chromosomal aberrations smaller than a few million base pairs generally cannot be seen on a karyogram.[6]

| Karyotypeof human chromosomes | |

|---|---|

| Female (XX) | Male (XY) |

|

|

| There are two copies of eachautosome(chromosomes 1–22) in both females and males. Thesex chromosomesare different: There are two copies of the X-chromosome in females, but males have a single X-chromosome and a Y-chromosome. | |

Autosomal genetic disorders[edit]

Autosomal genetic disorders can arise due to a number of causes, some of the most common beingnondisjunctionin parental germ cells orMendelian inheritanceof deleterious alleles from parents. Autosomal genetic disorders which exhibit Mendelian inheritance can be inherited either in anautosomal dominantor recessive fashion.[7]These disorders manifest in and are passed on by either sex with equal frequency.[7][8]Autosomal dominant disorders are often present in both parent and child, as the child needs to inherit only one copy of the deleteriousalleleto manifest the disease. Autosomal recessive diseases, however, require two copies of the deleterious allele for the disease to manifest. Because it is possible to possess one copy of a deleterious allele without presenting a disease phenotype, two phenotypically normal parents can have a child with the disease if both parents are carriers (also known asheterozygotes) for the condition.

Autosomalaneuploidycan also result in disease conditions. Aneuploidy of autosomes is not well tolerated and usually results in miscarriage of the developing fetus. Fetuses with aneuploidy of gene-rich chromosomes—such aschromosome 1—never survive to term,[9]and fetuses with aneuploidy of gene-poor chromosomes—such aschromosome 21— are still miscarried over 23% of the time.[10]Possessing a single copy of an autosome (known as a monosomy) is nearly always incompatible with life, though very rarely some monosomies can survive past birth. Having three copies of an autosome (known as a trisomy) is far more compatible with life, however. A common example isDown syndrome,which is caused by possessing three copies ofchromosome 21instead of the usual two.[9]

Partial aneuploidy can also occur as a result ofunbalanced translocationsduring meiosis.[11]Deletions of part of a chromosome cause partial monosomies, while duplications can cause partial trisomies. If the duplication or deletion is large enough, it can be discovered by analyzing a karyogram of the individual. Autosomal translocations can be responsible for a number of diseases, ranging fromcancertoschizophrenia.[12][13]Unlike single gene disorders, diseases caused by aneuploidy are the result of impropergene dosage,not nonfunctional gene product.[14]

See also[edit]

- Aneuploidy(abnormal number of chromosomes)

- Autosomal dominant

- Autosomal recessive

- Homologous chromosome

- Pseudoautosomal region

- XY sex-determination system

- Genetic disorder

References[edit]

- ^Griffiths, Anthony J. F. (1999).An Introduction to genetic analysis.New York: W.H. Freeman.ISBN978-0-7167-3771-1.

- ^"Autosomal DNA - ISOGG Wiki".isogg.org.Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2017.Retrieved28 April2018.

- ^"Autosome Definition(s)".Genetics Home Reference.Archived fromthe originalon 2 January 2016.Retrieved28 April2018.

- ^Foster JW, Dominguez-Steglich MA, Guioli S, Kwok C, Weller PA, Stevanović M, Weissenbach J, Mansour S, Young ID, Goodfellow PN (December 1994). "Complicate dysplasia and autosomal sex reversal caused by mutations in an SRY-related gene".Nature.372(6506): 525–30.Bibcode:1994Natur.372..525F.doi:10.1038/372525a0.PMID7990924.S2CID1472426.

- ^"Chromosome mapping Facts, information, pictures".encyclopedia.Encyclopedia articles about Chromosome mapping.Archivedfrom the original on 10 December 2015.Retrieved4 December2015.

- ^Nussbaum RL, McInnes RR, Willard HF, Hamosh A, Thompson MW (2007).Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine(7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p.69.ISBN9781416030805.

- ^ab"human genetic disease".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-10-13.Retrieved2015-10-16.

- ^Chial, Heidi (2008)."Mendelian Genetics: Patterns of Inheritance and Single-Gene Disorders".Nature Education.1(1): 63.

- ^abWang, Jin-Chen C. (2005-01-01). "Autosomal Aneuploidy". In Gersen, Steven L.; MEd, Martha B. Keagle (eds.).The Principles of Clinical Cytogenetics.Humana Press. pp. 133–164.doi:10.1385/1-59259-833-1:133.ISBN978-1-58829-300-8.

- ^Savva, George M.; Morris, Joan K.; Mutton, David E.; Alberman, Eva (June 2006). "Maternal age-specific fetal loss rates in Down syndrome pregnancies".Prenatal Diagnosis.26(6): 499–504.doi:10.1002/pd.1443.PMID16634111.S2CID34154717.

- ^"Translocation - Glossary Entry".Genetics Home Reference.2015-11-02.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-12-09.Retrieved2015-11-08.

- ^Strefford, Jonathan C.; An, Qian; Harrison, Christine J. (31 October 2014)."Modeling the molecular consequences of unbalanced translocations in cancer: Lessons from acute lymphoblastic leukemia".Cell Cycle.8(14): 2175–2184.doi:10.4161/cc.8.14.9103.PMID19556891.

- ^Klar, Amar J S (2002)."The chromosome 1;11 translocation provides the best evidence supporting genetic etiology for schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorders".Genetics.160(4): 1745–1747.doi:10.1093/genetics/160.4.1745.PMC1462039.PMID11973326.

- ^Disteche, Christine M. (15 December 2012)."Dosage Compensation of the Sex Chromosomes".Annual Review of Genetics.46(1): 537–560.doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155454.PMC3767307.PMID22974302.