Babylonia

This article includes a list of generalreferences,butit lacks sufficient correspondinginline citations.(May 2013) |

Babylonia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1894 BC–539 BC | |||||||||||

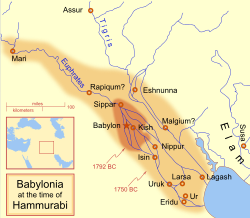

The extent of the Babylonian Empire at the start and end ofHammurabi's reign, located in what today is modern day Iraq and Iran | |||||||||||

| Capital | Babylon | ||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian Aramaic | ||||||||||

| Religion | Babylonian religion | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1894 BC | ||||||||||

| 539 BC | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History ofIraq |

|---|

|

|

|

| Ancient history |

|---|

| Preceded byprehistory |

|

Babylonia(⫽ˌbæbɪˈloʊniə⫽;Akkadian:𒆳𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠,māt Akkadī) was anancientAkkadian-speakingstateandcultural areabased in the city ofBabylonin central-southernMesopotamia(present-dayIraqand parts ofSyriaandIran). It emerged as an Akkadian populated butAmorite-ruled statec. 1894 BC.During the reign ofHammurabiand afterwards, Babylonia was retrospectively called "the country of Akkad" (māt Akkadīin Akkadian), a deliberate archaism in reference to the previous glory of theAkkadian Empire.[1][2]It was often involved in rivalry with the older ethno-linguistically related state ofAssyriain the north of Mesopotamia andElamto the east inAncient Iran.Babylonia briefly became the major power in the region after Hammurabi (fl.c. 1792–1752 BC middle chronology, orc. 1696–1654 BC,short chronology) created a short-lived empire, succeeding the earlier Akkadian Empire,Third Dynasty of Ur,andOld Assyrian Empire.The Babylonian Empire rapidly fell apart after the death of Hammurabi and reverted to a small kingdom centered around the city of Babylon.

LikeAssyria,the Babylonian state retained the written Akkadian language (the language of its native populace) for official use, despite itsNorthwest Semitic-speaking Amorite founders andKassitesuccessors, who spoke alanguage isolate,not being native Mesopotamians. It retained theSumerian languagefor religious use (as did Assyria which also shared the sameMesopotamian religionas Babylonia), but already by the time Babylon was founded, this was no longer a spoken language, having been wholly subsumed by Akkadian. The earlier Akkadian and Sumerian traditions played a major role in the descendant Babylonian and Assyrian culture, and the region would remain an important cultural center, even under its protracted periods of outside rule.

History[edit]

Pre-Babylonian Sumero-Akkadian period[edit]

Mesopotamia had already enjoyed a long history before the emergence of Babylon, withSumeriancivilization emerging in the regionc. 5400 BC,and the Akkadian-speakers who would go on to form Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia appearing somewhere between the 35th and 30th century BC.[3]

During the 3rd millennium BC, an intimate cultural symbiosis occurred between Sumerian and Akkadian-speakers, which included widespreadbilingualism.[4]The influence of Sumerian on Akkadian and vice versa is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.[4]This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the third millennium as asprachbund.[4] Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the third and the second millennium BC (the precise timeframe being a matter of debate).[5]Fromc. 5400 BCuntil the rise of the Akkadian Empire in the 24th century BC, Mesopotamia had been dominated by largelySumeriancities and city states, such asUr,Lagash,Uruk,Kish,Isin,Larsa,Adab,Eridu,Gasur,Assur,Hamazi,Akshak,ArbelaandUmma,although Semitic Akkadian names began to appear on the king lists of some of these states (such asEshnunnaandAssyria) between the 29th and 25th centuries BC. Traditionally, the major religious center of all Mesopotamia was the city ofNippurwhere the godEnlilwas supreme, and it would remain so until replaced byBabylonduring the reign of Hammurabi in the mid-18th century BC.[citation needed]TheAkkadian Empire(2334–2154 BC) saw the Akkadian Semites and Sumerians of Mesopotamia unite under one rule, and the Akkadians fully attain ascendancy over the Sumerians and indeed come to dominate much of the ancientNear East.The empire eventually disintegrated due to economic decline, climate change, and civil war, followed by attacks by the language isolate speaking Gutians from theZagros Mountainsto the northeast. Sumer rose up again with the Third Dynasty of Ur (Neo-Sumerian Empire) in the late 22nd century BC, and ejected the Gutians from southern Mesopotamia in 2161 BC as suggested by surviving tablets and astronomy simulations.[6]They also seem to have gained ascendancy over much of the territory of the Akkadian speaking kings of Assyria in northern Mesopotamia for a time.

Followed by the collapse of the Sumerian "Ur-III" dynasty at the hands of theElamitesin 2002 BC, theAmorites( "Westerners" ), a foreignNorthwest Semitic-speakingpeople, began to migrate into southern Mesopotamia from the northernLevant,gradually gaining control over most of southern Mesopotamia, where they formed a series of small kingdoms, while the Assyrians reasserted their independence in the north. The states of the south were unable to stem the Amorite advance, and for a time may have relied on their fellow Akkadians in Assyria for protection.[citation needed]

KingIlu-shuma(c. 2008–1975 BC) of the Old Assyrian period (2025–1750 BC) in a known inscription describes his exploits to the south as follows:

The freedom[n 1]of the Akkadians and their children I established. I purified their copper. I established their freedom from the border of the marshes and Ur and Nippur,Awal,and Kish,Derof the goddessIshtar,as far as the City of (Ashur).[7]

Past scholars originally extrapolated from this text that it means he defeated the invading Amorites to the south and Elamites to the east, but there is no explicit record of that, and some scholars believe the Assyrian kings were merely giving preferential trade agreements to the south.

These policies, whether military, economic or both, were continued by his successorsErishum IandIkunum.

However, whenSargon I(1920–1881 BC) succeeded as king in Assyria in 1920 BC, he eventually withdrew Assyria from the region, preferring to concentrate on continuing the vigorous expansion of Assyrian colonies inAnatoliaat the expense of theHurriansandHattiansand theAmoriteinhabitedLevant,and eventually southern Mesopotamia fell to the Amorites. During the first centuries of what is called the "Amorite period", the most powerfulcity-statesin the south wereIsin,EshnunnaandLarsa,together with Assyria in the north.

First Babylonian dynasty – Amorite dynasty, 1894–1595 BC[edit]

Around 1894 BC, an Amorite chieftain namedSumu-abumappropriated a tract of land which included the then relatively small city of Babylon from the neighbouring minor city-state ofKazallu,of which it had initially been a territory, turning his newly acquired lands into a state in its own right. His reign was concerned with establishing statehood amongst a sea of other minor city-states and kingdoms in the region. However, Sumu-abum appears never to have bothered to give himself the title ofKing of Babylon,suggesting that Babylon itself was still only a minor town or city, and not worthy of kingship.[9]

He was followed bySumu-la-El,Sabium,andApil-Sin,each of whom ruled in the same vague manner as Sumu-abum, with no reference to kingship of Babylon itself being made in any written records of the time.[10]Sin-Muballitwas the first of these Amorite rulers to be regarded officially as aking of Babylon,and then on only one single clay tablet. Under these kings, Babylonia remained a small nation which controlled very little territory, and was overshadowed by neighbouring kingdoms that were both older, larger, and more powerful, such as; Isin, Larsa, Assyria to the north and Elam to the east in ancient Iran.[11]The Elamites occupied huge swathes of southern Mesopotamia, and the early Amorite rulers were largely held in vassalage to Elam.

Empire of Hammurabi[edit]

Babylon remained a minor town in a small state until the reign of its sixth Amorite ruler,Hammurabi,during 1792–1750 BC (orc. 1728–1686 BC in theshort chronology).[11]He conducted major building work in Babylon, expanding it from a small town into a great city worthy of kingship. A very efficient ruler, he established a bureaucracy, with taxation and centralized government. Hammurabi freed Babylon from Elamite dominance, and indeed drove the Elamites from southern Mesopotamia entirely, invading Elam itself. He then systematically conquered southern Mesopotamia, including the cities of Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, Kish,Lagash,Nippur,Borsippa,Ur, Uruk, Umma, Adab,Sippar,Rapiqum,and Eridu.[12]His conquests gave the region stability after turbulent times, and coalesced the patchwork of small states into a single nation; it is only from the time of Hammurabi that southern Mesopotamia acquired the nameBabylonia.[13]

Hammurabi turned his disciplined armies eastwards and invaded the region which a thousand years later becameIran,conqueringElam,Gutium,Lullubi,TurukkuandKassites.To the west, he conquered the Amorite states of the Levant (modernSyriaandJordan) including the powerful kingdoms ofMariandYamhad.

Hammurabi then entered into a protracted war with theOld Assyrian Empirefor control of Mesopotamia and dominance of the Near East. Assyria had extended control over much of theHurrianandHattianparts of southeast Anatolia from the 21st century BC, and from the latter part of the 20th century BC had asserted itself over the northeast Levant and central Mesopotamia. After a protracted struggle over decades with the powerful Assyrian kingsShamshi-Adad IandIshme-Dagan I,Hammurabi forced their successorMut-Ashkurto pay tribute to Babylonc. 1751 BC,giving Babylonia control over Assyria's centuries-old Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Anatolia.[14]

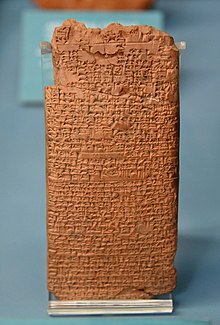

One of Hammurabi's most important and lasting works was the compilation of theBabylonian law code,which improved the much earlier codes ofSumer,Akkadand Assyria. This was made by order of Hammurabi after the expulsion of the Elamites and the settlement of his kingdom. In 1901, a copy of theCode of Hammurabiwas discovered on astelebyJacques de MorganandJean-Vincent ScheilatSusain Elam, where it had later been taken as plunder.[15]That copy is now in theLouvre.[16]

From before 3000 BC until the reign of Hammurabi, the major cultural and religious center of southern Mesopotamia had been the ancient city of Nippur, where the god Enlil was supreme. Hammurabi transferred this dominance to Babylon, makingMarduksupreme in the pantheon of southern Mesopotamia (with the godAshur,and to some degreeIshtar,remaining the long-dominant deity in northern Mesopotamian Assyria). The city of Babylon became known as a "holy city" where any legitimate ruler of southern Mesopotamia had to be crowned, and the city was also revered by Assyria for these religious reasons. Hammurabi turned what had previously been a minor administrative town into a large, powerful and influential city, extended its rule over the entirety of southern Mesopotamia, and erected a number of buildings.

The Amorite-ruled Babylonians, like their predecessor states, engaged in regular trade with the Amorite and Canaanite city-states to the west, with Babylonian officials or troops sometimes passing to the Levant and Canaan, and Amorite merchants operating freely throughout Mesopotamia. The Babylonian monarchy's western connections remained strong for quite some time.Ammi-Ditana,great-grandson of Hammurabi, still titled himself "king of the land of the Amorites". Ammi-Ditana's father and son also bore Amorite names:Abi-EshuhandAmmi-Saduqa.

Decline[edit]

Southern Mesopotamia had no natural, defensible boundaries, making it vulnerable to attack. After the death of Hammurabi, his empire began to disintegrate rapidly. Under his successorSamsu-iluna(1749–1712 BC) the far south of Mesopotamia was lost to a native Akkadian-speaking kingIlum-ma-iliwho ejected the Amorite-ruled Babylonians. The south became the nativeSealand Dynasty,remaining free of Babylon for the next 272 years.[17]

Both the Babylonians and their Amorite rulers were driven from Assyria to the north by an Assyrian-Akkadian governor namedPuzur-Sinc. 1740 BC,who regarded king Mut-Ashkur as both a foreign Amorite and a former lackey of Babylon. After six years of civil war in Assyria, a native king namedAdasiseized powerc. 1735 BC,and went on to appropriate former Babylonian and Amorite territory in central Mesopotamia, as did his successorBel-bani.

Amorite rule survived in a much reduced Babylon, Samshu-iluna's successorAbi-Eshuhmade a vain attempt to recapture the Sealand Dynasty for Babylon, but met defeat at the hands of kingDamqi-ilishu II.By the end of his reign Babylonia had shrunk to the small and relatively weak nation it had been upon its foundation, although the city itself was far larger and opulent than the small town it had been prior to the rise of Hammurabi.

He was followed byAmmi-Ditanaand thenAmmi-Saduqa,both of whom were in too weak a position to make any attempt to regain the many territories lost after the death of Hammurabi, contenting themselves with peaceful building projects in Babylon itself.

Samsu-Ditanawas to be the last Amorite ruler of Babylon. Early in his reign he came under pressure from theKassites,a people speaking an apparentlanguage isolateoriginating in the mountains of what is today northwest Iran. Babylon was then attacked by theIndo-European-speaking,Anatolia-basedHittitesin 1595 BC. Shamshu-Ditana was overthrown following the "sack of Babylon" by the Hittite kingMursili I.The Hittites did not remain for long, but the destruction wrought by them finally enabled their Kassite allies to gain control.

The sack of Babylon and ancient Near East chronology[edit]

The date of the sack of Babylon by the Hittites under kingMursili Iis considered crucial to the various calculations of the earlychronology of the ancient Near East,as it is taken as a fixed point in the discussion. Suggestions for its precise date vary by as much as 230 years, corresponding to the uncertainty regarding the length of the "Dark Age" of the much laterLate Bronze Age collapse,resulting in the shift of the entire Bronze Age chronology of Mesopotamia with regard to theEgyptian chronology.Possible dates for the sack of Babylon are:

- ultra-short chronology: 1499 BC

- short chronology: 1531 BC

- middle chronology: 1595 BC (probably the most commonly used, and often seen as having the most support)[18][19][20][21][22][23]

- long chronology: 1651 BC (favored by some astronomical events reconstruction)[6]

- ultra-long chronology: 1736 BC[24]

Mursili I,the Hittite king, first conqueredAleppo,capital ofYamhadkingdom to avenge the death of his father, but his main geopolitical target was Babylon.[25]The MesopotamianChronicle 40,written after 1500 BC, mentions briefly the sack of Babylon as: "During the time ofSamsu‐ditana,the Hittites marched on Akkad. "More details can be found in another source, theTelepinu Proclamation,a Hittite text from around 1520 BC, which states:[26]

"And then he [Mursili I] marched to Aleppo, and he destroyed Aleppo and brought captives and possessions of Aleppo to Ḫattuša. Then, however, he marched to Babylon, and he destroyed Babylon, and he defeated the Hurrian troops, and he brought captives and possessions of Babylon toḪattuša."

The movement of Mursili's troops was around 800 km from the conquered Aleppo to reach the Euphrates, located to the east, skirting around Assyria, and then to the south along the course of the river to reach finally Babylon. His conquest of Babylon brought to an end the dynasty of Hammurabi, and although the Hittite text, Telipinu Proclamation, does not mention Samsu-ditana, and the BabylonianChronicle 20does not mention a specific Hittite king either,Trevor Bryceconcludes that there is no doubt that both sources refer to Mursili I andSamsu-ditana.[25]

The Hittites, when sacking Babylon, removed the images of the godsMardukand his consortZarpanitufrom theEsagil templeand they took them to their kingdom. The later inscription ofAgum-kakrime,the Kassite king, claims he returned the images; and another later text, theMarduk Prophesy,written long after the events, mentions that the image of Marduk was in exile around twenty-four years.[26]

After the conquest, Mursili I did not attempt to convert the whole region he had occupied from Aleppo to Babylon as a part of his kingdom; he instead made an alliance with theKassites,and then a Kassite dynasty was established in Babylonia.[27]

Kassite dynasty, 1595–1155 BC[edit]

The Kassite dynasty was founded byGandashof Mari. The Kassites, like the Amorite rulers who had preceded them, were not originally native to Mesopotamia. Rather, they had first appeared in theZagros Mountainsof what is today northwestern Iran.

The ethnic affiliation of the Kassites is unclear. Still, their language was notSemiticorIndo-European,and is thought to have been either a language isolate or possibly related to theHurro-Urartian language familyof Anatolia,[28]although the evidence for its genetic affiliation is meager due to the scarcity of extant texts. That said, several Kassite leaders may have borneIndo-European names,and they may have had anIndo-Europeanelite similar to theMitannielite that later ruled over the Hurrians of central and eastern Anatolia, while others had Semitic names.[29][30]

The Kassites renamed BabylonKarduniašand their rule lasted for 576 years, the longest dynasty in Babylonian history.

This new foreign dominion offers a striking analogy to the roughly contemporary rule of the SemiticHyksosinancient Egypt.Most divine attributes ascribed to the Amorite kings of Babylonia disappeared at this time; the title "god" was never given to a Kassite sovereign. Babylon continued to be the capital of the kingdom and one of theholy citiesof western Asia, where the priests of theancient Mesopotamian religionwere all-powerful, and the only place where the right to inheritance of the short lived old Babylonian empire could be conferred.[31]

Babylonia experienced short periods of relative power, but in general proved to be relatively weak under the long rule of the Kassites, and spent long periods underAssyrianandElamitedomination and interference.

It is not clear precisely when Kassite rule of Babylon began, but the Indo-European Hittites from Anatolia did not remain in Babylonia for long after the sacking of the city, and it is likely the Kassites moved in soon afterwards.Agum IItook the throne for the Kassites in 1595 BC, and ruled a state that extended from Iran to the middle Euphrates; The new king retained peaceful relations withErishum III,the native Mesopotamian king of Assyria, but successfully went to war with theHittite Empire,and twenty-four years after, the Hittites took the sacredstatue of Marduk,he recovered it and declared the god equal to theKassite deityShuqamuna.

Burnaburiash Isucceeded him and drew up a peace treaty with the Assyrian kingPuzur-Ashur III,and had a largely uneventful reign, as did his successorKashtiliash III.

TheSealand Dynastyof southern Mesopotamia remained independent of Babylonia and like Assyria was in native Akkadian-speaking hands.Ulamburiashmanaged to attack it and conquered parts of the land fromEa-gamil,a king with a distinctly Sumerian name, around 1450 BC, whereuponEa-Gamilfled to his allies in Elam. The Sealand Dynasty region still remained independent, and the Kassite king seems to have been unable to finally conquer it. Ulamburiash began making treaties withancient Egypt,which then was ruling southernCanaan,and Assyria to the north.Agum IIIalso campaigned against the Sealand Dynasty, finally wholly conquering the far south of Mesopotamia for Babylon, destroying its capital Dur-Enlil in the process. From there Agum III extended farther south still, invading what was many centuries later to be called theArabian PeninsulaorArabia,and conquering thepre-Arabstate ofDilmun(in modernBahrain).

Karaindashbuilt a bas-relief temple in Uruk andKurigalzu I(1415–1390 BC) built a new capitalDur-Kurigalzunamed after himself, transferring administrative rule from Babylon. Both of these kings continued to struggle unsuccessfully against the Sealand Dynasty.Karaindashalso strengthened diplomatic ties with the Assyrian kingAshur-bel-nisheshuand the Egyptian PharaohThutmose IIIand protected Babylonian borders with Elam.

Kadašman-Ḫarbe Isucceeded Karaindash, and briefly invaded Elam before being eventually defeated and ejected by its king Tepti Ahar. He then had to contend with theSuteans,ancient Semitic-speaking peoplesfrom the southeastern Levant who invaded Babylonia and sacked Uruk. He describes having "annihilated their extensive forces", then constructed fortresses in a mountain region calledḪiḫi,in the desert to the west (modernSyria) as security outposts, and "he dug wells and settled people on fertile lands, to strengthen the guard".[32]

Kurigalzu Isucceeded the throne, and soon came into conflict with Elam, to the east. WhenḪur-batila,the successor ofTepti Ahartook the throne of Elam, he began raiding the Babylonia, taunting Kurigalzu to do battle with him atDūr-Šulgi.Kurigalzu launched a campaign which resulted in the abject defeat and capture of Ḫur-batila, who appears in no other inscriptions. He went on to conquer the eastern lands of Elam. This took his army to the Elamite capital, the city of Susa, which was sacked. After this a puppet ruler was placed on the Elamite throne, subject to Babylonia. Kurigalzu I maintained friendly relations with Assyria,Egyptand the Hittites throughout his reign.Kadashman-Enlil I(1374–1360 BC) succeeded him, and continued his diplomatic policies.

Burna-Buriash IIascended to the throne in 1359 BC, he retained friendly relations with Egypt, but the resurgentMiddle Assyrian Empire(1365–1050 BC) to the north was now encroaching into northern Babylonia, and as a symbol of peace, the Babylonian king took the daughter of the powerful Assyrian kingAshur-uballit Iin marriage. He also maintained friendly relations withSuppiluliuma I,ruler of theHittite Empire.

He was succeeded byKara-ḫardaš(who was half Assyrian, and the grandson of the Assyrian king) in 1333 BC, a usurper namedNazi-Bugašdeposed him, enragingAshur-uballit I,who invaded and sacked Babylon, slew Nazi-Bugaš, annexed Babylonian territory for the Middle Assyrian Empire, and installedKurigalzu II(1345–1324 BC) as his vassal ruler of Babylonia.

Soon afterArik-den-ilisucceeded the throne of Assyria in 1327 BC, Kurigalzu II attacked Assyria in an attempt to reassert Babylonian power. After some impressive initial successes he was ultimately defeated, and lost yet more territory to Assyria. Between 1307 BC and 1232 BC his successors, such asNazi-Maruttash,Kadashman-Turgu,Kadashman-Enlil II,Kudur-EnlilandShagarakti-Shuriash,allied with the empires of the Hittites and theMitanni(who were both also losing swathes of territory to the resurgent Assyrians), in a failed attempt to stop Assyrian expansion. This expansion, nevertheless, continued unchecked.

Kashtiliash IV's (1242–1235 BC) reign ended catastrophically as the Assyrian kingTukulti-Ninurta I(1243–1207 BC) routed his armies, sacked and burned Babylon and set himself up as king, ironically becoming the firstnativeMesopotamian to rule the Mesopotamian populated state, its previous rulers having all beennon-MesopotamianAmorites and Kassites.[17]Kashtiliash himself was taken to Ashur as a prisoner of war.

An Assyrian governor/king namedEnlil-nadin-shumiwas placed on the throne to rule as viceroy to Tukulti-Ninurta I, andKadashman-Harbe IIandAdad-shuma-iddinasucceeded as Assyrian governor/kings,also subject to Tukulti-Ninurta I until 1216 BC.

Babylon did not begin to recover until late in the reign ofAdad-shuma-usur(1216–1189 BC), as he too remained a vassal of Assyria until 1193 BC. However, he was able to prevent the Assyrian kingEnlil-kudurri-usurfrom retaking Babylonia, which, apart from its northern reaches, had mostly shrugged off Assyrian domination during a short period ofcivil warin the Assyrian empire, in the years after the death of Tukulti-Ninurta.

Meli-Shipak II(1188–1172 BC) seems to have had a peaceful reign. Despite not being able to regain northern Babylonia from Assyria, no further territory was lost, Elam did not threaten, and theLate Bronze Age collapsenow affecting the Levant,Canaan,Egypt,theCaucasus,Anatolia,Mediterranean,North Africa,northern Iran andBalkansseemed (initially) to have little impact on Babylonia (or indeed Assyria and Elam).

War resumed under subsequent kings such asMarduk-apla-iddina I(1171–1159 BC) andZababa-shuma-iddin(1158 BC). The long reigning Assyrian kingAshur-dan I(1179–1133 BC) resumed expansionist policies and conquered further parts of northern Babylonia from both kings, and the Elamite rulerShutruk-Nakhunteeventually conquered most of eastern Babylonia.Enlil-nadin-ahhe(1157–1155 BC) was finally overthrown and the Kassite dynasty ended after Ashur-dan I conquered yet more of northern and central Babylonia, and the equally powerful Shutruk-Nahhunte pushed deep into the heart of Babylonia itself, sacking the city and slaying the king. Poetical works have been found lamenting this disaster.

Despite the loss of territory, general military weakness, and evident reduction in literacy and culture, the Kassite dynasty was the longest-lived dynasty of Babylon, lasting until 1155 BC, when Babylon was conquered by Shutruk-Nakhunte of Elam, and reconquered a few years later by theNebuchadnezzar I,part of the larger Late Bronze Age collapse.

Early Iron Age – Native rule, second dynasty of Isin, 1155–1026 BC[edit]

The Elamites did not remain in control of Babylonia long, instead entering into an ultimately unsuccessful war with Assyria, allowingMarduk-kabit-ahheshu(1155–1139 BC) to establish theDynasty IV of Babylon, from Isin,with the first native Akkadian-speaking south Mesopotamian dynasty to rule Babylonia, with Marduk-kabit-ahheshu becoming only the second native Mesopotamian to sit on the throne of Babylon, after the Assyrian kingTukulti-Ninurta I.His dynasty was to remain in power for some 125 years. The new king successfully drove out the Elamites and prevented any possible Kassite revival. Later in his reign he went to war with Assyria, and had some initial success, briefly capturing the south Assyrian city ofEkallatumbefore ultimately suffering defeat at the hands ofAshur-Dan I.

Itti-Marduk-balatusucceeded his father in 1138 BC, and successfully repelled Elamite attacks on Babylonia during his 8-year reign. He too made attempts to attack Assyria, but also met with failure at the hands of the still reigning Ashur-Dan I.

Ninurta-nadin-shumitook the throne in 1127 BC, and also attempted an invasion of Assyria, his armies seem to have skirted through easternAramea(modern Syria) and then made an attempt to attack the Assyrian city ofArbela(modernErbil) from the west. However, this bold move met with defeat at the hands ofAshur-resh-ishi Iwho then forced a treaty in his favour upon the Babylonian king.

Nebuchadnezzar I(1124–1103 BC) was the most famous ruler of this dynasty. He fought and defeated the Elamites and drove them from Babylonian territory, invading Elam itself, sacking the Elamite capitalSusa,and recovering the sacred statue of Marduk that had been carried off from Babylon during the fall of the Kassites. Shortly afterwards, the king of Elam was assassinated and his kingdom disintegrated into civil war. However, Nebuchadnezzar failed to extend Babylonian territory further, being defeated a number of times byAshur-resh-ishi I(1133–1115 BC), king of theMiddle Assyrian Empire,for control of formerly Hittite-controlled territories inAramand Anatolia. The Hittite Empire of the northern and western Levant and eastern Anatolia had been largely annexed by the Middle Assyrian Empire, and its heartland finally overrun by invadingPhrygiansfrom theBalkans.In the later years of his reign, Nebuchadnezzar I devoted himself to peaceful building projects and securing Babylonia's borders against the Assyrians, Elamites and Arameans.

Nebuchadnezzar was succeeded by his two sons, firstlyEnlil-nadin-apli(1103–1100 BC), who lost territory to Assyria. The second of them,Marduk-nadin-ahhe(1098–1081 BC) also went to war with Assyria. Some initial success in these conflicts gave way to a catastrophic defeat at the hands of the powerful Assyrian kingTiglath-Pileser I(1115–1076 BC), who annexed huge swathes of Babylonian territory, thus further expanding the Assyrian Empire. Following this a terrible famine gripped Babylon, inviting attacks and migrations from the northwest Semitic tribes ofAramaeansandSuteansfrom the Levant.

In 1072 BCMarduk-shapik-zerisigned a peace treaty withAshur-bel-kala(1075–1056 BC) of Assyria, however, his successorKadašman-Buriašwas not so friendly to Assyria, prompting the Assyrian king to invade Babylonia and depose him, placingAdad-apla-iddinaon the throne as his vassal. Assyrian domination continued untilc. 1050 BC,withMarduk-ahhe-eribaandMarduk-zer-Xregarded as vassals of Assyria. After 1050 BC the Middle Assyrian Empire descended into a period of civil war, followed by constant warfare with theArameans,Phrygians,Neo-Hittite statesandHurrians,allowing Babylonia to once more largely free itself from the Assyrian yoke for a few decades.

However,East Semitic-speakingBabylonia soon began to suffer further repeated incursions fromWest Semiticnomadic peoples migrating from the Levant during theBronze Age collapse,and during the 11th century BC large swathes of the Babylonian countryside was appropriated and occupied by these newly arrivedArameansandSuteans.Arameans settled much of the countryside in eastern and central Babylonia and the Suteans in the western deserts, with the weak Babylonian kings being unable to stem these migrations.

Period of chaos, 1026–911 BC[edit]

The ruling Babylonian dynasty ofNabu-shum-liburwas deposed by marauding Arameans in 1026 BC, and the heart of Babylonia, including the capital city itself descended into anarchic state, and no king was to rule Babylon for over 20 years.

However, in southern Mesopotamia (a region corresponding with the old Dynasty of the Sealand), Dynasty V (1025–1004 BC) arose, this was ruled bySimbar-shipak,leader of a Kassite clan, and was in effect a separate state from Babylon. The state of anarchy allowed the Assyrian rulerAshur-nirari IV(1019–1013 BC) the opportunity to attack Babylonia in 1018 BC, and he invaded and captured the Babylonian city ofAtlilaand some south central regions of Mesopotamia for Assyria.

The south Mesopotamian dynasty was replaced by another Kassite Dynasty (Dynasty VI; 1003–984 BC) which also seems to have regained control over Babylon itself. The Elamites deposed this brief Kassite revival, with kingMar-biti-apla-usurfounding Dynasty VII (984–977 BC). However, this dynasty too fell, when the Arameans once more ravaged Babylon.

Babylonian rule was restored byNabû-mukin-apliin 977 BC, ushering in Dynasty VIII. Dynasty IX begins withNinurta-kudurri-usur II,who ruled from 941 BC. Babylonia remained weak during this period, with whole areas of Babylonia now under firm Aramean and Sutean control. Babylonian rulers were often forced to bow to pressure from Assyria and Elam, both of which had appropriated Babylonian territory.

Assyrian rule, 911–619 BC[edit]

Babylonia remained in a state of chaos as the 10th century BC drew to a close. A further migration of nomads from the Levant occurred in the early 9th century BC with the arrival of theChaldeans,another nomadic Northwest Semitic-speaking people described in Assyrian annals as the "Kaldu". The Chaldeans settled in the far southeast of Babylonia, joining the already long extant Arameans and Suteans. By 850 BC the migrant Chaldeans had established a small territory in the extreme southeast of Mesopotamia.

From 911 BC with the founding of theNeo-Assyrian Empire(911–605 BC) byAdad-nirari II,Babylon found itself once again under the domination and rule of its fellow Mesopotamian state for the next three centuries. Adad-nirari II twice attacked and defeatedShamash-mudammiqof Babylonia, anne xing a large area of land north of theDiyala Riverand the towns ofHītandZanquin mid Mesopotamia. He made further gains over Babylonia underNabu-shuma-ukin Ilater in his reign.Tukulti-Ninurta IIandAshurnasirpal IIalso forced Babylonia into vassalage, andShalmaneser III(859–824 BC) sacked Babylon itself, slew kingNabu-apla-iddina,subjugated the Aramean, Sutean and Chaldean tribes settled within Babylonia, and installedMarduk-zakir-shumi I(855–819 BC) followed byMarduk-balassu-iqbi(819–813 BC) as his vassals. It was during the late 850's BC, in the annals ofShalmaneser III,that theChaldeansandArabsdwelling in some northern regions of theArabian Peninsulaare first mentioned in the pages of written recorded history.

Upon the death of Shalmaneser II,Baba-aha-iddinawas reduced to vassalage by the Assyrian queenShammuramat(known asSemiramisto the Persians, Armenians and Greeks), acting as regent to his successorAdad-nirari IIIwho was merely a boy. Adad-nirari III eventually killed Baba-aha-iddina and ruled there directly until 800 BC untilNinurta-apla-Xwas crowned. However, he too was subjugated by Adad-Nirari III. The next Assyrian king,Shamshi-Adad Vthen made a vassal ofMarduk-bel-zeri.

Babylonia briefly fell to another foreign ruler whenMarduk-apla-usurascended the throne in 780 BC, taking advantage of a period of civil war in Assyria. He was a member of theChaldeantribe who had a century or so earlier settled in a small region in the far southeastern corner of Mesopotamia, bordering thePersian Gulfand southwestern Elam.Shalmaneser IVattacked him and retook northern Babylonia, forcing a border treaty in Assyria's favour upon him. However, he was allowed to remain on the throne, and successfully stabilised the part of Babylonia he controlled.Eriba-Marduk,another Chaldean, succeeded him in 769 BC and his son,Nabu-shuma-ishkunin 761 BC. Babylonia appears to have been in a state of chaos during this time, with the north occupied by Assyria, its throne occupied by foreign Chaldeans, and civil unrest prominent throughout the land.

The Babylonian kingNabonassaroverthrew the Chaldean usurpers in 748 BC, and successfully stabilised Babylonia, remaining untroubled byAshur-nirari Vof Assyria. However, with the accession ofTiglath-Pileser III(745–727 BC) Babylonia came under renewed attack. Babylon was invaded and sacked and Nabonassar reduced to vassalage. His successorsNabu-nadin-zeri,Nabu-suma-ukin IIandNabu-mukin-zeriwere also in servitude to Tiglath-Pileser III, until in 729 BC the Assyrian king decided to rule Babylon directly as its king instead of allowing Babylonian kings to remain as vassals of Assyria as his predecessors had done for two hundred years.

It was during this period thatEastern Aramaicwas introduced by the Assyrians as thelingua francaof the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and the still spoken (by Assyrians and Mandeans) Mesopotamian Aramaic began to slowly overlay and supplant Akkadian as the spoken language of the general populace of both Assyria and Babylonia.

The Assyrian kingShalmaneser Vwas declared king of Babylon in 727 BC, but died whilst besiegingSamariain 722 BC.

Marduk-apla-iddina II,a Chaldean malka (chieftain) of the far southeast of Mesopotamia, then fomented revolt against Assyrian domination, assisted by strong Elamite support. Marduk-apla-iddina managed to take the throne of Babylon itself between 721 and 710 BC whilst the Assyrian kingSargon II(722–705 BC) were otherwise occupied in defeating theScythiansandCimmerianswho had attacked Assyria'sPersianandMedianvassal colonies in ancient Iran. Marduk-apla-iddina II was eventually defeated and ejected bySargon IIof Assyria, and fled to his protectors in Elam.Sargon IIwas then declared king in Babylon.

Destruction of Babylon[edit]

Sennacherib(705–681 BC) succeeded Sargon II, and after ruling directly for a while, he placed his sonAshur-nadin-shumion the throne. However, Merodach-Baladan and his Elamite protectors continued to unsuccessfully agitate against Assyrian rule.Nergal-ushezib,an Elamite, murdered the Assyrian prince and briefly took the throne. This led the infuriated Assyrian kingSennacheribto invade and subjugate Elam and to sack Babylon, laying waste to the region and largely destroying the city. While praying to the godNisrochinNinevehin 681 BC, Sennacherib was soon murdered by his own sons. The new Assyrian kingEsarhaddonplaced a puppet kingMarduk-zakir-shumi IIon the throne in Babylon. However, Marduk-apla-iddina returned from exile in Elam, and briefly deposed Marduk-zakir-shumi, whereupon Esarhaddon was forced to attack and defeat him. Marduk-apla-iddina once more fled to his masters in Elam, where he died in exile.

Restoration and rebuilding[edit]

Esarhaddon(681–669 BC) ruled Babylon personally, he completely rebuilt the city, bringing rejuvenation and peace to the region. Upon his death, and in an effort to maintain harmony within his vast empire (which stretched from theCaucasustoEgyptandNubiaand fromCyprustoPersiaand theCaspian Sea), he installed his eldest sonShamash-shum-ukinas a subject king in Babylon, and his youngest, the highly educatedAshurbanipal(669–627 BC), in the more senior position as king of Assyria and overlord of Shamash-shum-ukin.

Babylonian revolt[edit]

Despite being an Assyrian himself, Shamash-shum-ukin, after decades subject to his brotherAshurbanipal,declared that the city of Babylon (and not the Assyrian city ofNineveh) should be the seat of the immense empire. He raised a major revolt against his brother, Ashurbanipal. He led a powerful coalition of peoples also resentful of Assyrian subjugation and rule, including Elam, thePersians,Medes,the Babylonians, Chaldeans and Suteans of southern Mesopotamia, the Arameans of the Levant and southwest Mesopotamia, theArabsandDilmunitesof the Arabian Peninsula and the Canaanites-Phoenicians. After a bitter struggle Babylon was sacked and its allies vanquished, Shamash-shum-ukim being killed in the process. Elam was destroyed once and for all, and the Babylonians, Persians, Chaldeans, Arabs, Medes, Elamites, Arameans, Suteans and Canaanites were violently subjugated, with Assyrian troops exacting savage revenge on the rebelling peoples. An Assyrian governor namedKandalanuwas placed on the throne to rule on behalf of the Assyrian king.[17]Upon Ashurbanipal's death in 627 BC, his sonAshur-etil-ilani(627–623 BC) became ruler of Babylon and Assyria.

However, Assyria soon descended into a series of brutal internal civil wars which were to cause its downfall. Ashur-etil-ilani was deposed by one of his own generals, namedSin-shumu-lishirin 623 BC, who also set himself up as king in Babylon. After only one year on the throne amidst continual civil war,Sinsharishkun(622–612 BC) ousted him as ruler of Assyria and Babylonia in 622 BC. However, he too was beset by constant unremitting civil war in the Assyrian heartland. Babylonia took advantage of this and rebelled underNabopolassar,a previously unknownmalka(chieftain) of the Chaldeans, who had settled in southeastern Mesopotamia by c. 850 BC.

It was during the reign of Sin-shar-ishkun that Assyria's vast empire began to unravel, and many of its former subject peoples ceased to pay tribute, most significantly for the Assyrians; the Babylonians, Chaldeans,Medes,Persians,Scythians,Arameans andCimmerians.

Neo-Babylonian Empire (Chaldean Empire)[edit]

In 620 BC Nabopolassar seized control over much of Babylonia with the support of most of the inhabitants, with only the city of Nippur and some northern regions showing any loyalty to the beleaguered Assyrian king.[17]Nabopolassar was unable to utterly secure Babylonia, and for the next four years he was forced to contend with an occupying Assyrian army encamped in Babylonia trying to unseat him. However, the Assyrian king, Sin-shar-ishkun was plagued by constant revolts among his people inNineveh,and was thus prevented from ejecting Nabopolassar.

The stalemate ended in 615 BC, when Nabopolassar entered the Babylonians and Chaldeans into alliance withCyaxares,an erstwhile vassal of Assyria, and king of theIranian peoples;theMedes,Persians,SagartiansandParthians.Cyaxares had also taken advantage of the Assyrian destruction of the formerly regionally dominant pre-Iranian Elamite andManneannations and the subsequent anarchy in Assyria to free theIranicpeoples from three centuries of the Assyrian yoke and regional Elamite domination. TheScythiansfrom north of theCaucasus,and theCimmeriansfrom theBlack Seawho had both also been subjugated by Assyria, joined the alliance, as did regional Aramean tribes.

In 615 BC, while the Assyrian king was fully occupied fighting rebels in both Babylonia and Assyria itself, Cyaxares launched a surprise attack on the Assyrian heartlands, sacking the cities ofKalhu(the BiblicalCalah,Nimrud) andArrapkha(modernKirkuk), Nabopolassar was still pinned down in southern Mesopotamia and thus not involved in this breakthrough.

From this point on the coalition of Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians, Cimmerians and Sagartians fought in unison against a civil war ravaged Assyria. Major Assyrian cities such as Ashur, Arbela (modernIrbil),Guzana,Dur Sharrukin(modernKhorsabad),Imgur-Enlil,Nibarti-Ashur,Gasur,Kanesh,Kar AshurnasipalandTushhanfell to the alliance during 614 BC. Sin-shar-ishkun somehow managed to rally against the odds during 613 BC, and drove back the combined forces ranged against him.

However, the alliance launched a renewed combined attack the following year, and after five years of fierce fightingNinevehwas sacked in late 612 BC after a prolonged siege, in which Sin-shar-ishkun was killed defending his capital.

House to house fighting continued in Nineveh, and an Assyrian general and member of the royal household, took the throne asAshur-uballit II(612–605 BC). He was offered the chance of accepting a position of vassalage by the leaders of the alliance according to theBabylonian Chronicle.However, he refused and managed to successfully fight his way out of Nineveh and to the northern Assyrian city ofHarraninUpper Mesopotamiawhere he founded a new capital. The fighting continued, as the Assyrian king held out against the alliance until 607 BC, when he was eventually ejected by the Medes, Babylonians, Scythians and their allies, and prevented in an attempt to regain the city the same year.

TheEgyptianPharaohNecho II,whose dynasty had been installed as vassals of Assyria in 671 BC, belatedly tried to aid Egypt's former Assyrian masters, possibly out of fear that Egypt would be next to succumb to the new powers without Assyria to protect them, having already been ravaged by theScythians.The Assyrians fought on with Egyptian aid until what was probably a final decisive victory was achieved against them atCarchemishin northwestern Assyria in 605 BC. The seat of empire was thus transferred to Babylonia[33]for the first time since Hammurabi over a thousand years before.

Nabopolassar was followed by his sonNebuchadnezzar II(605–562 BC), whose reign of 43 years made Babylon once more the ruler of much of the civilized world, taking over portions of the former Assyrian Empire, with the eastern and northeastern portion being taken by the Medes and the far north by theScythians.[33]

Nebuchadnezzar II may have also had to contend with remnants of the Assyrian resistance. Some sections of the Assyrian army and administration may have still continued in and aroundDur-Katlimmuin northwest Assyria for a time, however, by 599 BC Assyrian imperial records from this region also fell silent. The fate of Ashur-uballit II remains unknown, and he may have been killed attempting to regain Harran, at Carchemish, or continued to fight on, eventually disappearing into obscurity.

TheScythiansandCimmerians,erstwhile allies of Babylonia under Nabopolassar, now became a threat, and Nebuchadnezzar II was forced to march into Anatolia and rout their forces, ending the northern threat to his Empire.

The Egyptians attempted to remain in the Near East, possibly in an effort to aid in restoring Assyria as a secure buffer against Babylonia and the Medes and Persians, or to carve out an empire of their own. Nebuchadnezzar II campaigned against the Egyptians and drove them back over theSinai.However, an attempt to take Egypt itself as his Assyrian predecessors had succeeded in doing failed, mainly due to a series of rebellions from theIsraelitesofJudahand the former kingdom ofEphraim,thePhoeniciansofCaananand theArameansof the Levant. The Babylonian king crushed these rebellions, deposedJehoiakim,the king ofJudahand deported a sizeable part of the population to Babylonia. Cities likeTyre,SidonandDamascuswere also subjugated. TheArabsand other South Arabian peoples who dwelt in the deserts to the south of the borders of Mesopotamia were then also subjugated.

In 567 BC he went to war with PharaohAmasis,and briefly invadedEgyptitself. After securing his empire, which included marrying a Median princess, he devoted himself to maintaining the empire and conducting numerous impressive building projects in Babylon. He is credited with building the fabledHanging Gardens of Babylon.[34]

Amel-Marduksucceeded to the throne and reigned for only two years. Little contemporary record of his rule survives, thoughBerosuslater stated that he was deposed and murdered in 560 BC by his successorNeriglissarfor conducting himself in an "improper manner".

Neriglissar(560–556 BC) also had a short reign. He was the son in law of Nebuchadnezzar II, and it is unclear if he was a Chaldean or native Babylonian who married into the dynasty. He campaigned in Aram and Phoenicia, successfully maintaining Babylonian rule in these regions. Neriglissar died young however, and was succeeded by his sonLabashi-Marduk(556 BC), who was still a boy. He was deposed and killed during the same year in a palace conspiracy.

Of the reign of the last Babylonian king,Nabonidus(Nabu-na'id,556–539 BC) who is the son of theAssyrianpriestessAdda-Guppiand who managed to kill the last Chaldean king, Labashi-Marduk, and took the reign, there is a fair amount of information available. Nabonidus (hence his son, the regentBelshazzar) was, at least from the mother's side, neither Chaldean nor Babylonian, but ironically Assyrian, hailing from its final capital ofHarran(Kharranu). His father's origins remain unknown. Information regarding Nabonidus is chiefly derived from a chronological tablet containing the annals of Nabonidus, supplemented by another inscription of Nabonidus where he recounts his restoration of the temple of the Moon-godSinat Harran; as well as by a proclamation of Cyrus issued shortly after his formal recognition as king of Babylonia.[33]

A number of factors arose which would ultimately lead to the fall of Babylon. The population of Babylonia became restive and increasingly disaffected under Nabonidus. He excited a strong feeling against himself by attempting to centralize the polytheistic religion of Babylonia in the temple of Marduk at Babylon, and while he had thus alienated the local priesthoods, the military party also despised him on account of his antiquarian tastes. He seemed to have left the defense of his kingdom to his sonBelshazzar(a capable soldier but poor diplomat who alienated the political elite), occupying himself with the more congenial work of excavating the foundation records of the temples and determining the dates of their builders.[33]He also spent time outside Babylonia, rebuilding temples in the Assyrian city of Harran, and also among his Arab subjects in the deserts to the south of Mesopotamia. Nabonidus and Belshazzar's Assyrian heritage is also likely to have added to this resentment. In addition, Mesopotamian military might had usually been concentrated in the martial state of Assyria. Babylonia had always been more vulnerable to conquest and invasion than its northern neighbour, and without the might of Assyria to keep foreign powers in check and Mesopotamia dominant, Babylonia was ultimately exposed.

It was in the sixth year of Nabonidus (549 BC) thatCyrus the Great,the Achaemenid Persian "king ofAnshan"in Elam, revolted against his suzerainAstyages,"king of the Manda" or Medes, atEcbatana.Astyages' army betrayed him to his enemy, and Cyrus established himself at Ecbatana, thus putting an end to the empire of the Medes and making the Persian faction dominant among the Iranic peoples.[35]Three years later Cyrus had become king of all Persia, and was engaged in a campaign to put down a revolt among the Assyrians. Meanwhile, Nabonidus had established a camp in the desert of his colony of Arabia, near the southern frontier of his kingdom, leaving his sonBelshazzar(Belsharutsur) in command of the army.

In 539 BC Cyrus invaded Babylonia. A battle was fought atOpisin the month of June, where the Babylonians were defeated; and immediately afterwards Sippar surrendered to the invader. Nabonidus fled to Babylon, where he was pursued byGobryas,and on the 16th day ofTammuz,two days after the capture of Sippar, "the soldiers of Cyrus entered Babylon without fighting." Nabonidus was dragged from his hiding place, where the services continued without interruption. Cyrus did not arrive until the 3rd ofMarchesvan(October), Gobryas having acted for him in his absence. Gobryas was now made governor of the province of Babylon, and a few days afterwards Belshazzar the son of Nabonidus died in battle. A public mourning followed, lasting six days, and Cyrus' sonCambysesaccompanied the corpse to the tomb.[36]

One of the first acts of Cyrus accordingly was to allow theJewish exilesto return to their own homes, carrying with them their sacred temple vessels. The permission to do so was embodied in a proclamation, whereby the conqueror endeavored to justify his claim to the Babylonian throne.[36]

Cyrus now claimed to be the legitimate successor of the ancient Babylonian kings and the avenger ofBel-Marduk,who was assumed to be wrathful at the impiety of Nabonidus in removing the images of the local gods from their ancestral shrines to his capital Babylon.[36]

The Chaldean tribe had lost control of Babylonia decades before the end of the era that sometimes bears their name, and they appear to have blended into the general populace of Babylonia even before this (for example, Nabopolassar, Nebuchadnezzar II and their successors always referred to themselves asShar Akkadand never asShar Kalduon inscriptions), and during the PersianAchaemenid Empirethe termChaldeanceased to refer to a race of people, and instead specifically to a social class of priests educated in classical Babylonian literature, particularly Astronomy and Astrology. By the midSeleucid Empire(312–150 BC) period this term too had fallen from use.

Fall of Babylon[edit]

Babylonia was absorbed into theAchaemenid Empirein 539 BCE, becoming thesatrapyof Babirush (Old Persian:𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽,romanized:Bābiruš).

A year before Cyrus' death, in 529 BCE, he elevated his sonCambyses IIin the government, making him king of Babylon. He reserved for himself the fuller title of "king of the (other) provinces" of the empire. It was only whenDarius Iacquired the Persian throne and ruled it as a representative of theZoroastrian religion,that the old tradition was broken and the claim of Babylon to confer legitimacy on the rulers ofWest Asiaceased to be acknowledged.[36]

Immediately after Darius seized Persia, Babylonia briefly recovered its independence under a native ruler, Nidinta-Bel, who took the name ofNebuchadnezzar III,and reigned from October 522 BC to August 520 BC, when Darius took the city by storm, during this period Assyria to the north also rebelled. A few years later, probably 514 BC, Babylon again revolted under theUrartiankingNebuchadnezzar IV;on this occasion, after its capture by the Persians, the walls were partly destroyed. TheEsagila,the great temple ofMarduk,however, still continued to be kept in repair and to be a center of Babylonian religious feelings.[36]

Alexander the Greatconquered Babylon in 333 BCE for theGreeks,and died there in 323 BCE. Babylonia and Assyria then became part of the GreekSeleucid Empire.[citation needed]It has long been maintained that the foundation ofSeleuciadiverted the population to the new capital ofLower Mesopotamiaand that the ruins of the old city became a quarry for the builders of the new seat of government,[36]but the recent publication of theBabylonian Chronicleshas shown that urban life was still very much the same well into theParthian Empire(150 BCE to 226 CE). The Parthian kingMithridatesconquered the region into the Parthian Empire in 150 BC, and the region became something of a battleground between Greeks and Parthians.

There was a brief interlude ofRomanconquest (the provinces ofAssyriaandMesopotamia;116–118 AD) underTrajan,after which the Parthians reasserted control.

Thesatrapyof Babylonia was absorbed intoAsōristān(Middle Persianfor "the land of Assyria" ) in theSasanian Empire,which began in 226 CE, and by this timeEast Syriac Rite Christianity,which emerged in Assyria and Upper Mesopotamia the first century, had become the dominant religion among theAssyrian people,who had never adopted theZoroastrianismorHellenistic religionor the languages of their rulers.

Apart from the small2nd century BCto3rd centuryindependent Neo-Assyrian states ofAdiabene,Osroene,Assur,Beth Garmai,Beth NuhadraandHatrain the north, Mesopotamia remained under largely Persian control until theArabMuslim conquest of Persiain the seventh century AD. Asōristān was dissolved as a geopolitical entity in 637, and the nativeEastern Aramaic-speaking and largely Christian populace of southern and central Mesopotamia (with the exception of theMandeans) gradually underwentArabizationandIslamizationin contrast to northern Mesopotamia where anAssyrian continuityendures to the present day.

Culture[edit]

Bronze Age to Early Iron Age Mesopotamian culture is sometimes summarized as "Assyro-Babylonian", because of the close ethnic, linguistic and cultural interdependence of the two political centers. The term "Babylonia", especially in writings from around the early 20th century, was formerly used to also include Southern Mesopotamia's earliestpre-Babylonianhistory, and not only in reference to the later city-state of Babylon proper. This geographic usage of the name "Babylonia" has generally been replaced by the more accurate termSumerorSumero-Akkadianin more recent writing, referring to the pre-Assyro-Babylonian Mesopotamian civilization.

Babylonian culture[edit]

Art and architecture[edit]

In Babylonia, an abundance ofclay,and lack ofstone,led to greater use ofmudbrick;Babylonian, Sumerian and Assyrian temples were massive structures of crude brick which were supported bybuttresses,the rain being carried off by drains. One such drain atUrwas made oflead.The use of brick led to the early development of thepilasterand column, and offrescoesand enameled tiles. The walls were brilliantly coloured, and sometimes plated withzincorgold,as well as withtiles.Paintedterracottacones for torches were also embedded in the plaster. In Babylonia, in place of therelief,there was greater use of three-dimensional figures—the earliest examples being theStatues of Gudea,that are realistic if somewhat clumsy. The paucity of stone in Babylonia made every pebble precious, and led to a high perfection in the art of gem-cutting.[38]

Astronomy[edit]

Tablets dating back to theOld Babylonian perioddocument the application of mathematics to the variation in the length of daylight over a solar year. Centuries of Babylonian observations of celestial phenomena are recorded in the series ofcuneiform scripttablets known as the 'Enūma Anu Enlil'. The oldest significant astronomical text that we possess is Tablet 63 of 'Enūma Anu Enlil', the Venus tablet ofAmmi-Saduqa,which lists the first and last visible risings of Venus over a period of about 21 years and is the earliest evidence that the phenomena of a planet were recognized as periodic. The oldest rectangularastrolabedates back to Babyloniac. 1100 BC.TheMUL.APIN,contains catalogues of stars and constellations as well as schemes for predictingheliacal risingsand the settings of the planets, lengths of daylight measured by awater clock,gnomon,shadows, andintercalations.The Babylonian GU text arranges stars in 'strings' that lie along declination circles and thus measure right-ascensions or time-intervals, and also employs the stars of the zenith, which are also separated by given right-ascensional differences.[39][40][41]

Medicine[edit]

Medical diagnosis and prognosis

We find [medical semiotics] in a whole constellation of disciplines.... There was a real common ground among these [Babylonian] forms of knowledge... an approach involving analysis of particular cases, constructed only through traces, symptoms, hints.... In short, we can speak about a symptomatic or divinatory [or conjectural] paradigm which could be oriented toward past present or future, depending on the form of knowledge called upon. Toward future... that was the medical science of symptoms, with its double character, diagnostic, explaining past and present, and prognostic, suggesting likely future....

The oldestBabylonian(i.e., Akkadian) texts onmedicinedate back to theFirst Babylonian dynastyin the first half of the2nd millennium BC[43]although the earliest medical prescriptions appear in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur period.[44]The most extensive Babylonian medical text, however, is theDiagnostic Handbookwritten by theummânū,or chief scholar,Esagil-kin-apliofBorsippa,[45]during the reign of the Babylonian kingAdad-apla-iddina(1069–1046 BC).[46]

Along with contemporaryancient Egyptian medicine,the Babylonians introduced the concepts ofdiagnosis,prognosis,physical examination,andprescriptions.In addition, theDiagnostic Handbookintroduced the methods oftherapyandaetiologyand the use ofempiricism,logicandrationalityin diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. The text contains a list of medicalsymptomsand often detailed empiricalobservationsalong with logical rules used in combining observed symptoms on the body of apatientwith its diagnosis and prognosis.[47]

The symptoms and diseases of a patient were treated through therapeutic means such asbandages,creamsandpills.If a patient could not be cured physically, the Babylonian physicians often relied onexorcismto cleanse the patient from anycurses.Esagil-kin-apli'sDiagnostic Handbookwas based on a logical set ofaxiomsand assumptions, including the modern view that through the examination and inspection of the symptoms of a patient, it is possible to determine the patient'sdisease,its aetiology and future development, and the chances of the patient's recovery.[45]

Esagil-kin-apli discovered a variety of illnesses and diseases and described their symptoms in hisDiagnostic Handbook.These include the symptoms for many varieties ofepilepsyand related ailments along with their diagnosis and prognosis.[48]Later Babylonian medicine resembles earlyGreek medicinein many ways. In particular, the early treatises of theHippocratic Corpusshow the influence of late Babylonian medicine in terms of both content and form.[49]

Literature[edit]

There were libraries in most towns and temples; an old Sumerian proverb averred that "he who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn". Women as well as men learned to read and write,[50][51]and in Semitic times, this involved knowledge of the extinct Sumerian language, and a complicated and extensivesyllabary.[50]

A considerable amount of Babylonian literature was translated from Sumerian originals, and the language of religion and law long continued to be written in the old agglutinative language of Sumer. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. The characters of the syllabary were all arranged and named, and elaborate lists of them were drawn up.[50]

There are many Babylonian literary works whose titles have come down to us. One of the most famous of these was theEpic of Gilgamesh,in twelve books, translated from the original Sumerian by a certainSin-liqi-unninni,and arranged upon an astronomical principle. Each division contains the story of a single adventure in the career ofGilgamesh.The whole story is a composite product, and it is probable that some of the stories are artificially attached to the central figure.[50]

Neo-Babylonian culture[edit]

The brief resurgence of Babylonian culture in the 7th to 6th centuries BC was accompanied by a number of important cultural developments.

Astronomy[edit]

Among the sciences,astronomyandastrologystill occupied a conspicuous place in Babylonian society. Astronomy was of old standing in Babylonia. Thezodiacwas a Babylonian invention of great antiquity; andeclipsesof thesunandmooncould be foretold.[50]There are dozens of cuneiform records of original Mesopotamian eclipse observations.

Babylonian astronomy was the basis for much of what was done inancient Greek astronomy,in classical, in Sasanian,Byzantineand Syrian astronomy,astronomy in the medieval Islamic world,and inCentral AsianandWestern Europeanastronomy.[50][39]Neo-Babylonian astronomy can thus be considered the direct predecessor of much of ancientGreek mathematicsand astronomy, which in turn is the historical predecessor of the European (Western)scientific revolution.[52]

During the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Babylonian astronomers developed a new approach to astronomy. They began studyingphilosophydealing with the ideal nature of the earlyuniverseand began employing aninternal logicwithin their predictive planetary systems. This was an important contribution to astronomy and thephilosophy of scienceand some scholars have thus referred to this new approach as the first scientific revolution.[53]This new approach to astronomy was adopted and further developed in Greek and Hellenistic astronomy.

InSeleucidand Parthian times, the astronomical reports were of a thoroughly scientific character;[50]how much earlier their advanced knowledge and methods were developed is uncertain. The Babylonian development of methods for predicting the motions of the planets is considered to be a major episode in thehistory of astronomy.

The only Babylonian astronomer known to have supported aheliocentricmodel of planetary motion wasSeleucus of Seleucia(b. 190 BC).[54][55][56]Seleucus is known from the writings ofPlutarch.He supported the heliocentric theory where theEarth rotatedaround its own axis which in turn revolved around theSun.According toPlutarch,Seleucus even proved the heliocentric system, but it is not known what arguments he used.

Mathematics[edit]

Babylonian mathematical texts are plentiful and well edited.[52]In respect of time they fall in two distinct groups: one from theFirst Babylonian dynastyperiod (1830–1531 BC), the other mainlySeleucidfrom the last three or four centuries BC. In respect of content there is scarcely any difference between the two groups of texts. Thus Babylonian mathematics remained stale in character and content, with very little progress or innovation, for nearly two millennia.[dubious–discuss][52]

The Babylonian system of mathematics wassexagesimal,or a base 60numeral system.From this we derive the modern-day usage of 60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour, and 360 (60 × 6) degrees in a circle. The Babylonians were able to make great advances in mathematics for two reasons. First, the number 60 has manydivisors(2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, and 30), making calculations easier. Additionally, unlike the Egyptians and Romans, the Babylonians had a true place-value system, where digits written in the left column represented larger values (much as in our base-ten system: 734 = 7×100 + 3×10 + 4×1). Among the Babylonians' mathematical accomplishments were the determination of thesquare root of twocorrectly to seven places (YBC 7289). They also demonstrated knowledge of thePythagorean theoremwell before Pythagoras, as evidenced by this tablet translated by Dennis Ramsey and dating toc. 1900 BC:

4 is the length and 5 is the diagonal. What is the breadth? Its size is not known. 4 times 4 is 16. And 5 times 5 is 25. You take 16 from 25 and there remains 9. What times what shall I take in order to get 9? 3 times 3 is 9. 3 is the breadth.

Thenerof 600 and thesarof 3600 were formed from the unit of 60, corresponding with a degree of theequator.Tablets of squares and cubes, calculated from 1 to 60, have been found atSenkera,and a people acquainted with the sun-dial, the clepsydra, the lever and the pulley, must have had no mean knowledge of mechanics. Acrystallens, turned on thelathe,was discovered byAusten Henry LayardatNimrudalong with glass vases bearing the name of Sargon; this could explain the excessive minuteness of some of the writing on the Assyrian tablets, and a lens may also have been used in the observation of the heavens.[57]

The Babylonians might have been familiar with the general rules for measuring the areas. They measured the circumference of a circle as three times the diameter and the area as one-twelfth the square of the circumference, which would be correct if π were estimated as 3. The volume of a cylinder was taken as the product of the base and the height, however, the volume of the frustum of a cone or a square pyramid was incorrectly taken as the product of the height and half the sum of the bases. Also, there was a recent discovery in which a tablet used π as 3 and 1/8. The Babylonians are also known for the Babylonian mile, which was a measure of distance equal to about 11 kilometres (7 mi) today. This measurement for distances eventually was converted to a time-mile used for measuring the travel of the Sun, therefore, representing time. (Eves, Chapter 2) The Babylonians used also space time graphs to calculate the velocity of Jupiter. This is an idea that is considered highly modern, traced to the 14th century England and France and anticipating integral calculus.[58]

Philosophy[edit]

The origins of Babylonian philosophy can be traced back to early Mesopotamianwisdom literature,which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularlyethics,in the forms ofdialectic,dialogs,epic poetry,folklore,hymns,lyrics,prose,andproverbs.Babylonianreasoningandrationalitydeveloped beyondempiricalobservation.[59]

It is possible that Babylonian philosophy had an influence onGreek philosophy,particularlyHellenistic philosophy.The Babylonian textDialogue of Pessimismcontains similarities to theagonisticthought of thesophists,theHeracliteandoctrine of contrasts, and the dialogs ofPlato,as well as a precursor to themaieuticSocratic methodofSocrates.[60]TheMilesianphilosopherThalesis also known to have studied philosophy in Mesopotamia.

According to theassyriologistMarc Van de Mieroop,Babylonian philosophy was a highly developed system of thought with a unique approach to knowledge and a focus on writing,lexicography,divination, and law.[61]It was also abilingualintellectual culture, based onSumerianandAkkadian.[62]

Legacy[edit]

Babylonia, and particularly its capital city Babylon, has long held a place in theAbrahamic religionsas a symbol of excess and dissolute power. Many references are made to Babylon in theBible,both literally (historical) and allegorically. The mentions in theTanakhtend to be historical or prophetic, whileNew Testamentapocalyptic references to theWhore of Babylonare more likely figurative, or cryptic references possibly to pagan Rome, or some other archetype. The legendaryHanging Gardens of Babylonand theTower of Babelare seen as symbols of luxurious and arrogant power respectively.

Early Christians sometimes referred to Rome as Babylon. For instance, the writer of theFirst Epistle of Peterconcludes his letter with this advice: "She who is in Babylon [Rome], chosen together with you, sends you her greetings, and so does my son Mark." (1 Peter 5:13).

Revelation 14:8says: "A second angel followed and said, 'Fallen! Fallen is Babylon the Great,' which made all the nations drink the maddening wine of her adulteries". Other examples can be found inRevelation 16:19andRevelation 18:2.

Babylon is mentioned in the Quran in verse 102 of chapter 2 of SurahBaqarah(The Cow):

They ˹instead˺ followed the magic promoted by the devils during the reign of Solomon. Never did Solomon disbelieve, rather the devils disbelieved. They taught magic to the people, along with what had been revealed to the two angels, Hârût and Mârût, in Babylon. The two angels never taught anyone without saying, "We are only a test ˹for you˺, so do not abandon ˹your˺ faith." Yet people learned ˹magic˺ that caused a rift ˹even˺ between husband and wife; although their magic could not harm anyone except by Allah's Will. They learned what harmed them and did not benefit them—although they already knew that whoever buys into magic would have no share in the Hereafter. Miserable indeed was the price for which they sold their souls, if only they knew!

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Freedom = Akk.addurāru.

References[edit]

- ^"Aliraqi – Babylonian Empire".Archived fromthe originalon 2015-02-21.Retrieved2015-02-21.

- ^"Babylonian Empire – Livius".

- ^"Babylonia".HISTORY.Retrieved2021-10-08.

- ^abcDeutscher, Guy(2007).Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation.Oxford University Press US.pp. 20–21.ISBN978-0-19-953222-3.

- ^Woods C. 2006 "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian". In S.L. Sanders (ed)Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture:91–120 Chicago[1]Archived2013-04-29 at theWayback Machine

- ^abKhalisi, Emil (2020),The Double Eclipse at the Downfall of Old Babylon,arXiv:2007.07141

- ^A. K. Grayson (1972).Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, Volume 1.Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 7–8.

- ^Roux, Georges(27 August 1992),"The Time of Confusion",Ancient Iraq,Penguin Books,p. 266,ISBN9780141938257

- ^Robert William Rogers, A History of Babylonia and Assyria, Volume I, Eaton and Mains, 1900.

- ^Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2018-02-05).A History of Babylon, 2200 BC – AD 75.John Wiley & Sons. p. 69.ISBN978-1-4051-8898-2.

- ^abBryce, Trevor (2016).Babylonia: A Very Short Introduction.Oxford University Press. pp. 8–10.ISBN978-0-19-872647-0.

- ^Publishing, Britannica Educational (2010-04-01).Mesopotamia: The World's Earliest Civilization.Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 71.ISBN978-1-61530-208-6.

- ^Liverani, Mario (2013-12-04).The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy.Routledge. p. 242.ISBN978-1-134-75084-9.

- ^Oppenheim Ancient Mesopotamia

- ^Geographic, National (2021-11-30).Lost Cities, Ancient Tombs: A History of the World in 100 Discoveries.Disney Electronic Content. pp. 144–145.ISBN978-1-4262-2199-6.

- ^Barmash, Pamela (2020-09-24).The Laws of Hammurabi: At the Confluence of Royal and Scribal Traditions.Oxford University Press. p. 2.ISBN978-0-19-752542-5.

- ^abcdGeorges Roux,Ancient Iraq

- ^van de Mieroop, M.(2007).A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC.Malden: Blackwell.ISBN978-0-631-22552-2.

- ^Liverani, Mario(2013).The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy.Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East".ISBN9781134750917.

- ^Akkermans, Peter M.M.G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003).The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000–300 BC).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-79666-0.

- ^Sagona, A.; Zimansky, P. (2009).Ancient Turkey.London: Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-28916-0.

- ^Manning, S.W.; Kromer, B.; Kuniholm, P.I.; Newton, M.W. (2001). "Anatolian Tree Rings and a New Chronology for the East Mediterranean Bronze-Iron Ages".Science.294(5551): 2532–2535.doi:10.1126/science.1066112.PMID11743159.

- ^Sturt W. Manning et al., Integrated Tree-Ring-Radiocarbon High-Resolution Timeframe to Resolve Earlier Second Millennium BCE Mesopotamian Chronology, PlosONE July 13, 2016

- ^Eder, Christian., Assyrische Distanzangaben und die absolute Chronologie Vorderasiens, AoF 31, 191–236, 2004.

- ^abBryce, Trevor, (2005).The Kingdom of the Hittites,New Edition, Oxford University Press, pp. 97, 98.

- ^abBeaulieu, Paul-Alain, (2018).A History of Babylon, 2200 BC-AD 75,Wiley Blackwell, pp. 118, 119.

- ^Bryce, Trevor, (2005).The Kingdom of the Hittites,New Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 99.

- ^Schneider, Thomas (2003). "Kassitisch und Hurro-Urartäisch. Ein Diskussionsbeitrag zu möglichen lexikalischen Isoglossen".Altorientalische Forschungen(in German) (30): 372–381.

- ^"India: Early Vedic period".Encyclopædia Britannica Online.Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.Retrieved8 September2012.

- ^"Iranian art and architecture".Encyclopædia Britannica Online.Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.Retrieved8 September2012.

- ^Sayce 1911,p. 104.

- ^H. W. F. Saggs (2000).Babylonians.British Museum Press. p. 117.

- ^abcdSayce 1911,p. 105.

- ^"World Wide Sechool".History of Phoenicia – Part IV.Archived fromthe originalon 2007-01-01.Retrieved2007-01-09.

- ^Sayce 1911,pp. 105–106.

- ^abcdefSayce 1911,p. 106.

- ^Al-Gailani Werr, L., 1988. Studies in the chronology and regional style of Old Babylonian Cylinder Seals. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica, Volume 23.

- ^Sayce 1911,p. 108.

- ^abPingree, David(1998), "Legacies in Astronomy and Celestial Omens", inDalley, Stephanie(ed.),The Legacy of Mesopotamia,Oxford University Press, pp. 125–137,ISBN978-0-19-814946-0

- ^Rochberg, Francesca (2004),The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture,Cambridge University Press

- ^Evans, James (1998).The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy.Oxford University Press. pp. 296–297.ISBN978-0-19-509539-5.Retrieved2008-02-04.

- ^Ginzburg, Carlo(1984). "Morelli, Freud, and Sherlock Holmes: Clues and Scientific Method". InEco, Umberto;Sebeok, Thomas(eds.).The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce.Bloomington, IN: History Workshop, Indiana University Press. pp.81–118.ISBN978-0-253-35235-4.LCCN82049207.OCLC9412985.Ginzburg stresses the significance of Babylonian medicine in his discussion of the conjectural paradigm as evidenced by the methods ofGiovanni Morelli,Sigmund FreudandSherlock Holmesin the light ofCharles Sanders Peirce's logic of making educated guesses orabductive reasoning

- ^Leo Oppenheim (1977).Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization.University of Chicago Press. p.290.

- ^R D. Biggs (2005). "Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health in Ancient Mesopotamia".Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies.19(1): 7–18.

- ^abH. F. J. Horstmanshoff, Marten Stol, Cornelis Tilburg (2004),Magic and Rationality in Ancient Near Eastern and Graeco-Roman Medicine,p. 99,Brill Publishers,ISBN90-04-13666-5.

- ^Marten Stol (1993),Epilepsy in Babylonia,p. 55,Brill Publishers,ISBN90-72371-63-1.

- ^H. F. J. Horstmanshoff, Marten Stol, Cornelis Tilburg (2004),Magic and Rationality in Ancient Near Eastern and Graeco-Roman Medicine,p. 97–98,Brill Publishers,ISBN90-04-13666-5.

- ^Marten Stol (1993),Epilepsy in Babylonia,p. 5,Brill Publishers,ISBN90-72371-63-1.

- ^M. J. Geller (2004). H. F. J. Horstmanshoff; Marten Stol; Cornelis Tilburg (eds.).West Meets East: Early Greek and Babylonian Diagnosis.Vol. 27.Brill Publishers.pp. 11–186.ISBN978-90-04-13666-3.PMID17152166.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^abcdefgSayce 1911,p. 107.

- ^Tatlow, Elisabeth MeierWomen, Crime, and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The Ancient Near EastContinuum International Publishing Group Ltd. (31 March 2005)ISBN978-0-8264-1628-5p. 75[2]

- ^abcAaboe, A. (1992). Babylonian mathematics, astrology, and astronomy. In J. Boardman, I. Edwards, E. Sollberger, & N. Hammond (Eds.),The Cambridge Ancient History(The Cambridge Ancient History, pp. 276–292).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521227179.010

- ^D. Brown (2000),Mesopotamian Planetary Astronomy-Astrology,Styx Publications,ISBN90-5693-036-2.

- ^Otto E. Neugebauer(1945). "The History of Ancient Astronomy Problems and Methods",Journal of Near Eastern Studies4(1), pp. 1–38.

- ^George Sarton(1955). "Chaldaean Astronomy of the Last Three Centuries B.C.",Journal of the American Oriental Society75(3), pp. 166–173 [169].

- ^William P. D. Wightman (1951, 1953),The Growth of Scientific Ideas,Yale University Press p. 38.

- ^Sayce 1911,pp. 107–108.

- ^Ossendrijver, Mathieu (29 January 2016)."Ancient Babylonian astronomers calculated Jupiter's position from the area under a time-velocity graph".Science.351(6272): 482–484.Bibcode:2016Sci...351..482O.doi:10.1126/science.aad8085.PMID26823423.S2CID206644971.

- ^Giorgio Buccellati (1981), "Wisdom and Not: The Case of Mesopotamia",Journal of the American Oriental Society101(1), pp. 35–47.

- ^Giorgio Buccellati (1981), "Wisdom and Not: The Case of Mesopotamia",Journal of the American Oriental Society101(1), pp. 35–47 [43].

- ^Philosophy before the Greeks2015,pp. vii–viii, 187–188.

- ^Philosophy before the Greeks2015,p. 218.

Bibliography[edit]

- Theophilus G. Pinches,The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria(Many deities' names are now read differently, but this detailed 1906 work is a classic.)

- Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Sayce, Archibald Henry(1911). "Babylonia and Assyria".InChisholm, Hugh(ed.).Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Sayce, Archibald Henry(1878)..In Baynes, T. S. (ed.).Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 3 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 182–194.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913)..Catholic Encyclopedia.New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- The History FilesAncient Mesopotamia