Bai Juyi

Bai Juyi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait of Bai Juyi byChen Hongshou | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 772 Xinzheng,Henan,China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 846 (aged 73–74) Xiangshan Temple, Longmen (Luoyang),Henan,China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Musician, poet, politician | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Bai Acui (son) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Bai Huang (grandfather) Bai Jigeng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | Bạch Cư Dị | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Letian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | NhạcThiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | NhạcThiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xiangshan Jushi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | HươngSơnCư sĩ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Householderof Mount Xiang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 백거이 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | Bạch Cư Dị | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | Bạch Cư Dị | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | はく きょい | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bai Juyi(alsoBo JuyiorPo Chü-i;Chinese:Bạch Cư Dị;772–846),courtesy nameLetian( yên vui ), was a Chinese musician, poet, and politician during theTang dynasty.Many of his poems concern his career or observations made about everyday life, including as governor of three different provinces. He achieved fame as a writer of verse in a low-key, near vernacular style that was popular throughout medieval East Asia.[1]

Bai was also influential in the historical development ofJapanese literature,where he is better known by theon'yomireading of his courtesy name,Haku Rakuten(shinjitai:Bạch lặc thiên ).[2]His younger brotherBai Xing gianwas a short story writer.

Among his most famous works are the long narrative poems "Chang Hen Ge"(" Song of Everlasting Sorrow "), which tells the story ofYang Guifei,and "Pipa xing"(" Song of the Pipa ").

Life

[edit]Bai Juyi lived during theMiddle Tangperiod. This was a period of rebuilding and recovery for the Tang Empire, following theAn Lushan Rebellion,and following the poetically flourishing era famous forLi Bai(701-762),Wang Wei(701-761), andDu Fu(712-770). Bai Juyi lived through the reigns of eight or nine emperors, being born in theDaliregnal era (766-779) ofEmperor Daizong of Tang.He had a long and successful career both as a government official and a poet, although these two facets of his career seemed to have come in conflict with each other at certain points. Bai Juyi was also a devotedChan Buddhist.[3]

Birth and childhood

[edit]Bai Juyi was born in 772[4]inTaiyuan,Shanxi,which was then a few miles from location of the modern city, although he was inZhengyang,Henanfor most of his childhood. His family was poor but scholarly, his father being an Assistant Department Magistrate of the second-class.[5]At the age of ten he was sent away from his family to avoid a war that broke out in the north of China, and went to live with relatives in the area known asJiangnan,more specificallyXuzhou.Bai Juyi's father died in 794, his father's death caused his family to undergo hard times.[6]

Early career

[edit]Bai Juyi's official was delayed by seven years due to his father's death.[7]He passed thejinshiexaminations in 800. Bai Juyi may have taken up residence in the western capital city ofChang'an,in 801. Not long after this, Bai Juyi formed a long friendship with ascholarYuan Zhen.806, the first full year of the reign ofEmperor Xianzong of Tang,was the year when Bai Juyi was appointed to a minor post as a government official, atZhouzhi,which was not far from Chang'an (and also inShaanxiprovince). He was made a member (scholar) of theHanlin Academy,in 807, and Reminder of the Left from 807 until 815,[citation needed]except when in 811 his mother died, and he spent the traditional three-year mourning period again along the Wei River, before returning to court in the winter of 814, where he held the title of Assistant Secretary to the Prince's Tutor.[8]It was not a high-ranking position, but nevertheless one which he was soon to lose.

Exile

[edit]

While serving as a minor palace official in 814, Bai managed to get himself in official trouble. He made enemies at court and with certain individuals in other positions. It was partly his written works which led him into trouble. He wrote two long memorials, translated by Arthur Waley as "On Stopping the War", regarding what he considered to be an overly lengthy campaign against a minor group ofTatars;and he wrote a series of poems, in which he satirized the actions of greedy officials and highlighting the sufferings of the common folk.[9]

At this time, one of the post-An Lushanwarlords (jiedushi),Wu YuanjiinHenan,had seized control of Zhangyi Circuit (centered inZhumadian), an act for which he sought reconciliation with the imperial government, trying to get an imperial pardon as a necessary prerequisite. Despite the intercession of influential friends, Wu was denied, thus officially putting him in the position of rebellion. Still seeking a pardon, Wu turned to assassination, blaming the Prime Minister,Wu Yuanheng,and other officials: the imperial court generally began by dawn, requiring the ministers to rise early in order to attend in a timely manner; and, on July 13, 815, before dawn, the Tang Prime Minister Wu Yuanheng was set to go to the palace for a meeting with Emperor Xianzong. As he left his house, arrows were fired at his retinue. His servants all fled, and the assassins seized Wu Yuanheng and his horse, and then decapitated him, taking his head with them. The assassins also attacked another official who favored the campaign against the rebellious warlords, Pei Du, but was unable to kill him. The people at the capital were shocked and there was turmoil, with officials refusing to leave their personal residences until after dawn.

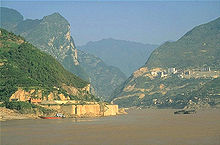

In this context, Bai Juyi overstepped his minor position by memorializing the emperor. As Assistant Secretary to the Prince's Tutor, Bai's memorial was a breach of protocol — he should have waited for those of censorial authority to take the lead before offering his own criticism. This was not the only charge which his opponents used against him. His mother had died, apparently caused by falling into a well while looking at some flowers, and two poems written by Bai Juyi — the titles of which Waley translates as "In Praise of Flowers" and "The New Well" — were used against him as a sign of lack ofFilial Piety,one of theConfucianideals. The result was exile. Bai Juyi was demoted to the rank of Sub-Prefect and banished from the court and the capital city toJiu gian g,then known as Xun Yang, on the southern shores of theYangtze Riverin northwestJiangxiProvince. After three years, he was sent as Governor of a remote place in Sichuan.[10]At the time, the main travel route there was up the Yangzi River. This trip allowed Bai Juyi a few days to visit his friend Yuan Zhen, who was also in exile and with whom he explored the rock caves located atYichang.Bai Juyi was delighted by the flowers and trees for which his new location was noted. In 819, he was recalled back to the capital, ending his exile.[11]

Return to the capital and a new emperor

[edit]In 819, Bai Juyi was recalled to the capital and given the position of second-class Assistant Secretary.[12]In 821, China got a new emperor,Muzong.After succeeding to the throne, Muzong spent his time feasting and heavily drinking and neglecting his duties as emperor. Meanwhile, the temporarily subdued regional military governors,jiedushi,began to challenge the central Tang government, leading to the new de facto independence of three circuits north of theYellow River,which had been previously subdued by Emperor Xianzong. Furthermore, Muzong's administration was characterized by massive corruption. Again, Bai Juyi wrote a series of memorials in remonstrance.

As Governor of Hangzhou

[edit]Again, Bai Juyi was sent away from the court and the capital, but this time to the important position of the thriving town ofHangzhou,which was at the southern terminus of theGrand Canaland located in the scenic neighborhood ofWest Lake.Fortunately for their friendship, Yuan Zhen at the time was serving an assignment in nearbyNingbo,also in what is todayZhe gian g,so the two could occasionally get together,[12]at least until Bai Juyi's term as Governor expired.

As governor of Hangzhou, Bai Juyi realized that the farmland nearby depended on the water of West Lake, but, due to the negligence of previous governors, the olddikehad collapsed and the lake had dried out to the point that the local farmers were suffering from severe drought. He ordered the construction of a stronger and taller dike, with adamto control the flow of water, thus providing water for irrigation, relieving the drought, and improving the livelihood of the local people over the following years. Bai Juyi used his leisure time to enjoy the beauty of West Lake, visiting the lake almost every day. He ordered the construction of a causeway to allow walking on foot, instead of requiring the services of a boat. A causeway in the West Lake (Baisha Causeway, bạch sa đê ) was later referred to as Bai Causeway in Bai Juyi's honor, but the original causeway built by Bai Juyi named Baigong Causeway (Bạch công đê) no longer exists.

Life near Luoyang

[edit]In 824, Bai Juyi's commission as governor expired, and he received the nominal rank of Imperial Tutor, which provided more in the way of official salary than official duties, and he relocated his household to a suburb of the "eastern capital,"Luoyang.[13]At the time, Luoyang was known as the eastern capital of the empire and was a major metropolis with a population of around one million and a reputation as the "cultural capital," as opposed to the more politically oriented capital ofChang'an.

Governor of Suzhou

[edit]

In 825, at age 53, Bai Juyi was given the position of Governor (Prefect) ofSuzhou,situated on the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and on the shores ofLake Tai.For the first two years, he enjoyed himself with feasts and picnic outings, but after a couple years he became ill and was forced into a period of retirement.[14]

Later career

[edit]After his time asPrefectofHangzhou(822-824) and thenSuzhou(825-827), Bai Juyi returned to the capital. He then served in various official posts in the capital, and then again as prefect/governor, this time inHenan,the province in which Luoyang was located. It was in Henan that his first son was born, though only to die prematurely the next year. In 831 Yuan Zhen died.[14]For the next thirteen years, Bai Juyi continued to hold various nominal posts but actually lived in retirement.

Retirement

[edit]

In 832, Bai Juyi repaired an unused part of the Xiangshan Monastery, atLongmen,about 7.5 miles south of Luoyang. Bai Juyi moved to this location, and began to refer to himself as the "Hermit of Xiangshan". This area, now aUNESCO World Heritage Site,is famous for its tens of thousands of statues ofBuddhaand his disciples carved out of the rock. In 839, he experienced a paralytic attack, losing the use of his left leg, and became a bedridden invalid for several months. After his partial recovery, he spent his final years arranging his Collected Works, which he presented to the main monasteries of those localities in which he had spent time.[15]

Death

[edit]

In 846, Bai Juyi died, leaving instructions for a simple burial in a grave at the monastery, with a plain style funeral, and to not have a posthumous title conferred upon him.[16]He has a tomb monument in Longmen, situated on Xiangshan across the Yi River from theLongmencave temples in the vicinity ofLuoyang,Henan.It is a circular mound of earth 4 metres (13 ft) high and 52 metres (171 ft) in circumference, with a 2.8-metre (9 ft 2 in) tall monument inscribed "Bai Juyi".

Works

[edit]Bai Juyi has been known for his plain, direct, and easily comprehensible style of verse, as well as for his social and political criticism. Besides his surviving poems, several letters and essays are also extant.

He collected his writings in the anthology called theBai Zhi Wen Ji.[4]

History

[edit]One of the most prolific of the Tang poets, Bai Juyi wrote over 2,800poems,which he had copied and distributed to ensure their survival. They are notable for their relative accessibility: it is said that he would rewrite any part of a poem if one of his servants was unable to understand it. The accessibility of Bai Juyi's poems made them extremely popular in his lifetime, in bothChinaandJapan,and they continue to be read in these countries today. His writings are also popular inKoreaandVietnam.

Famous poems

[edit]One of Bai's most famous poems is "Chang hen ge"(" Song of Everlasting Sorrow "), a longnarrativepoem that tells the story of the famous Tang dynasty concubineYang Guifeiand her relationship withEmperor Xuanzong of Tang.

Han's sovereign prized the beauty of flesh, he longed for such as ruins domains; |

Hán hoàng trọng sắc tư khuynh quốc, |

| — "Song of Lasting Pain" (Chang hen geTrường hận ca), opening lines (Stephen Owen,trans.)[17] |

Another of Bai's famous poems is "The Song of thePipaPlayer ". LikeDu Fu,Bai had a strong sense of social responsibility and is well known for his satirical poems, such asThe Elderly Charcoal Seller.Also he wrote about military conflicts during the Tang dynasty. Poems like "Song of Everlasting Sorrow" were examples of the peril in China during the An Lushan rebellion.

Bai Juyi also wrote intensely romantic poems to fellow officials with whom he studied and traveled. These speak of sharing wine, sleeping together, and viewing the Moon and mountains. One friend, Yu Shunzhi, sent Bai aboltof cloth as a gift from a far-off posting, and Bai Juyi debated on how best to use the precious material:

About to cut it to make a mattress,

pitying the breaking of the leaves;

about to cut it to make a bag,

pitying the dividing of the flowers.

It is better to sew it,

making a coverlet of joined delight;

I think of you as if I'm with you,

day or night.[18]

Bai's works were also highly renowned in Japan, and many of his poems were quoted and referenced inThe Tale of GenjibyMurasaki Shikibu.[19]Zeami Motokiyoalso quoted from Bai, in hisNoh plays,and even wrote one,Haku Rakuten,about the Japanese god of poetry repelling the Chinese poet from Japan, in opposition to Bai's (perceived) challenge to the country's poetic autonomy.[20]

Japanese painting byKanō Sansetsu(1590-1651).

Poetic forms

[edit]Bai Juyi was known for his interest in the oldyuefuform of poetry, which was a typical form ofHan poetry,namely folk ballad verses, collected or written by theMusic Bureau.[21]These were often a form of social protest. And, in fact, writing poetry to promote social progress was explicitly one of his objectives.[21]He is also known for his well-written poems in theregulated versestyle.

Art criticism

[edit]Bai was a poet of the middle Tang dynasty. It was a period after theAn Lushan Rebellion,theTang Empirewas in rebuilding and recovery. As a government official and a litterateur, Bai observed the court music performance that was seriously affected by Xiyu (Tây Vực,Western regions), and he made some articles with indignation to criticize that phenomenon. As an informal leader of a group of poets who rejected the courtly style of the time and emphasized the didactic function of literature, Bai believing that every literary work should contain a fitting moral and a well-defined social purpose.[22]That makes him not satisfied with cultural performance styles of Tang court.

For instance, in his work ofFaqu ge(Pháp khúc ca), translated asModel Music,is a poem regard to a kind of performing art, he made the following statement: "All the faqu's now are combined with songs from thebarbarians;but the barbarian music sounds evil and disordered whereas Han music sounds harmonious! "(Pháp khúc pháp khúc hợp di ca, di thanh tà loạn hoa thanh cùng)[23]

Faqu is a kind of performing style of Yanyue, a part of court music performance. In this poem, Bai Juyi strongly criticized Tang Daqu, which was itself heavily influenced by some nonnative musical elements absent in the Han Daqu-the original form of Daqu. Tang culture was an amalgamation of the culture of the ethnic Han majority, the culture of the "Western Region"(Tây Vực), andBuddhism.[23]The conflict between the mainstreamHan cultureandminorityculture exposed after the An Lushan Rebellion. The alien culture was so popular and it had seriously threatened the status of Han culture.

Musical performances at the Tang court are of two types: seated performances (Ngồi bộ) and standing performances (Lập bộ). Seated performances were conducted in smaller halls with a limited number of dancers, and emphasized refined artistry. Standing performances involves numerous dancers, and were usually performed in courtyards or squares intended for grand presentations.

Bai's another poem,Libuji(Lập bộ kĩ), translated asStanding Section Players,reflected the phenomenon of "decline in imperial court music".[24]In this poem, Bai mercilessly pointed out that music style of both seated performances and standing performances were deeply influenced by foreign culture.

Seated performances are more elegant than standing performances. Players in the Seating Section were the most qualified performers, while the performing level of the players in the Standing Section were a bit poor (Lập bộ tiện, ngồi bộ quý). In Bai Juyi's time, those two performances were full of foreign music, theYayue(Nhã nhạc,literally: "elegant music" ) was no longer be performed in those two sections. The Yayue music was only performed by the players who were eliminated from those two sections (Lập bộ lại lui chỗ nào nhậm, thủy liền nhạc huyền thao nhã âm).[25]This poem shows the culture changing in the middle Tang dynasty and the decline of Yayue, a form of classical music and dance performed at the royal court and temples

In those two poems of Bai reflected the situation of political and culture in the middle Tang dynasty after the An Lushan Rebellion, and he was concerned that the popularity of foreign music could lead the Tang society into chaos.

The pipa in the poems of Bai Juyi represents the expression of love, the action of communicating, and especially the poet's feelings on listening to music.[26]

Appraisal

[edit]Bai Juyi is considered one of the greatest Chinese poets, but even during the ninth century, sharp divide in critical opinions of his poetry already existed.[27]While some poets likePi Rixiuonly had the highest praise for Bai Juyi, others were hostile, like Sikong Tu (Tư Không đồ) who described Bai as "overbearing in force, yet feeble in energy (qi), like domineering merchants in the market place. "[27]Bai's poetry was immensely popular in his own lifetime, but his popularity, his use of vernacular, the sensual delicacy of some of his poetry, led to criticism of him being "common" or "vulgar". In a tomb inscription for Li Kan (Lý kham), a critic of Bai, poetDu Muwrote, couched in the words of Li Kan: "...It has bothered me that ever since theYuanhe Reignwe have had poems by Bai Juyi andYuan Zhenwhose sensual delicacy has defied the norms. Excepting gentlemen of mature strength and classical decorum, many have been ruined by them. They have circulated among the common people and been inscribed on walls; mothers and fathers teach them to sons and daughters orally, through winter's cold and summer's heat their lascivious phrases and overly familiar words have entered people's flesh and bone and cannot be gotten out. I have no position and cannot use the law to bring this under control. "[28]

Bai was also criticized for his "carelessness and repetitiveness", especially his later works.[29]He was nevertheless placed by Tang poet Zhang Wei (Trương vi) in his Schematic of Masters and Followers Among the Poets (Thi nhân chủ khách đồ) at the head of his first category: "extensive and grand civilizing power".[29]

Modern assessment

[edit]Burton Watsonsays of Bai Juyi: "he worked to develop a style that was simple and easy to understand, and posterity has requited his efforts by making him one of the most well-loved and widely read of all Chinese poets, both in his native land and in the other countries of the East that participate in the appreciation of Chinese culture. He is also, thanks to the translations and biographical studies byArthur Waley,one of the most accessible to English readers ".[30]

In popular culture

[edit]Bai Juyi is one of the main characters of the 2017 Chinese fantasy filmLegend of the Demon Cat,where he is portrayed byHuang Xuan.It the movie, the poet is solving a murder mystery and struggles to finish his famous poem, "Song of Everlasting Regret."

The American poet,Allen Ginsberg,wrote "Reading Bai Juyi" during his 1984 trip to China. The poem was written inShanghaiover the course of one day and the final section is a "transformation" (Ginsberg's description) of a poem by Bai.[31]

See also

[edit]- Li Shidao

- List of emperors of the Tang dynasty

- Salt in Chinese history#The moral debate over salt and society

- West Lake

Works cited

[edit]- Hinsch, Bret. (1990).Passions of the Cut Sleeve.University of California Press.

- Hinton, David(2008).Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology.New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.ISBN0-374-10536-7/ISBN978-0-374-10536-5.

- Owen, Stephen(1996).An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911.New York: W.W. Norton.ISBN0-393-97106-6.

- Owen, Stephen (2006).The Late Tang: Chinese Poetry of the Mid-Ninth Century (827-860).Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 45–.ISBN978-0-674-03328-3.

- Kubin, Wolfgang (=Wolfgang Kubin,book review ),Weigui Fang,'Den Kranich fragen. 155 Gedichte von Bai Juyi,in: ORIENTIERUNGEN. Zeitschrift zur Kultur Asiens (Journal sur la culture de l'Asie), n ° 1/2007, pp. 129–130.

- Nienhauser, William H (ed.).The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature.Indiana University Press 1986.ISBN0-253-32983-3

- Ueki, Hisayuki; Uno, Naoto; Matsubara, Akira (1999). "Shijin to Shi no Shōgai (Haku Kyoi)". In Matsuura, Tomohisa (ed.).Kanshi no JitenHán thơ の sự điển(in Japanese). Tokyo: Taishūkan Shoten. pp. 123–127.OCLC41025662.

- Arthur Waley,The Life and Times of Po Chü-I, 772-846 A.D(New York,: Macmillan, 1949). 238p.

- Waley, Arthur(1941).Translations from the Chinese.New York: Alfred A. Knopf.ISBN978-0-394-40464-6

- Watson, Burton(1971).Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century.(New York: Columbia University Press).ISBN0-231-03464-4

References

[edit]- ^Norwich, John Julius (1985–1993).Oxford illustrated encyclopedia.Judge, Harry George., Toyne, Anthony. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. p. 29.ISBN0-19-869129-7.OCLC11814265.

- ^Arntzen, S (2008) A Shared Heritage of Sensibility?: The Reception of Bai Juyi's Poetry in Japan. Paper presented at the conferenceJapan-China Cultural Relationsat theUniversity of Victoria,25th Jan.[1]Archived2014-01-12 at theWayback Machine

- ^Hinton, 266

- ^abUeki et al. 1999,p. 123.

- ^Waley (1941), 126-27.

- ^Waley (1941), p. 15.

- ^Waley (1941),

- ^Waley (1941), 126- 130

- ^Waley (1941), 130

- ^Waley (1941), 130-31, Waley refers to this place as "Chung-chou".

- ^Waley (1941), 130-31

- ^abWaley (1941), 131

- ^Waley (1941), 131. Waley refers to this village as "Li-tao-li."

- ^abWaley (1941), 132

- ^Waley (1941), 132-33

- ^Waley (1941), 133

- ^Owen (1996),p. 442.

- ^Hinsch, 80-81

- ^Bai Juyi (Chinese poet) fromBritannica

- ^A Waley,The Noh Plays of Japan(1976) p. 185

- ^abHinton, 265

- ^"Bai Juyi | Chinese poet".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2018-11-22.

- ^abCheung, Vincent C. K. "Daqu:theGesamtkunstwerkof Ancient China ".CiteSeerX10.1.1.590.6908.

- ^"BAI JUYI AND THE NEW YUEFU MOVEMENT"(PDF).

- ^"Từ 《 bảy đức vũ 》 cùng 《 lập bộ kĩ 》 xem Bạch Cư Dị" thứ nhã nhạc chi thế "- Trung Quốc biết võng".kns.cnki.net.Retrieved2018-11-22.

- ^Yu, CHunzhe (2004). "Bai Juyi shige zhong de Tangdai pipa yishu".Jiaoxiang: Xi'an Yinyue Xueyuan Xuebao/Jiaoxiang: Journal of Xi'an Conservatory of Music.

- ^abOwen (2006), pg. 45

- ^Owen (2006), pg. 277

- ^abOwen (2006), pp. 45-47, 57

- ^Watson, 184.

- ^Ginsberg, Allen (1997).Collected Poems: 1947-1997.New York: HarperPerennial. pp. 905–910.

External links

[edit]- Works by Juyi BaiatProject Gutenberg

- Works by or about Bai Juyiat theInternet Archive

- Works by Bai JuyiatLibriVox(public domain audiobooks)

- Bai Juyi: Poems— English translations of Bai Juyi's poetry.

- Translations of Chinese poems

- Chinese poems in translation

- Six Bai Juyi's poemsincluded in300 Selected Tang Poems,translated byWitter Bynner

- Article on the Shanghai Oriental Pearl Tower that was based on a poem by Bai Juyi

- English translation of Bai Juyi's "A Poem for the Swallows(《 yến thơ 》 /《 yến thơ kỳ Lưu tẩu 》)"

- Books of theQuan Tangshithat include collected poems of Bai Juyi at theChinese Text Project:

- Book 429,Book 430,Book 431,Book 432,Book 433,

- Book 434,Book 435,Book 436,Book 437,Book 438,

- Book 439,Book 440,Book 441,Book 442,Book 443,

- Book 444,Book 445,Book 446,Book 447,Book 448,

- Book 449,Book 450,Book 451,Book 452,Book 453,

- Book 454,Book 455,Book 456,Book 457,Book 458,

- Book 459,Book 460,Book 461,Book 462

- 772 births

- 846 deaths

- 9th-century Chinese musicians

- 8th-century Chinese poets

- 9th-century Chinese poets

- Buddhist poets

- Tang dynasty Buddhists

- Tang dynasty musicians

- Guqin players

- Musicians from Henan

- Poets from Henan

- Politicians from Zhengzhou

- Tang dynasty poets

- Tang dynasty government officials

- Three Hundred Tang Poems poets

- Writers from Zhengzhou