Balloon shark

| Balloon shark | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Subdivision: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Scyliorhinidae |

| Genus: | Cephaloscyllium |

| Species: | C. sufflans

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cephaloscyllium sufflans (Regan,1921)

| |

| |

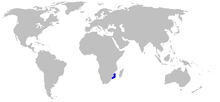

| Range of the balloon shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Scyliorhinus sufflansRegan, 1921 | |

Theballoon shark(Cephaloscyllium sufflans) is aspeciesofcatshark,and part of thefamilyScyliorhinidae,endemicto the southwesternIndian OceanoffSouth AfricaandMozambique.Benthicin nature, it is found over sandy and muddy flats at depths of 40–600 m (130–1,970 ft). This thick-bodied species has a broad, flattened head and a short tail; its distinguishing traits include narrow, lobe-like skin flaps in front of the nostrils, and a dorsal color pattern of faint darker saddles on a light grayish background.

Befitting itscommon name,the balloon shark can inflate itself with water or air as a defense againstpredators.It feeds on a variety ofcrustaceans,cephalopods,andfishes.Reproduction isoviparous,with females producingegg casestwo at a time. This species iscaught incidentallyinbottom trawlsbut does not seem to be threatened by fishing pressure, hence its assessment as near threatened by theInternational Union for Conservation of Nature(IUCN).

Taxonomy

[edit]BritishichthyologistCharles Tate Regandescribed the balloon shark asScyliorhinus sufflansin a 1921 issue of thescientific journalAnnals and Magazine of Natural History.He placed the species within the subgenusCephaloscyllium,which later authors have elevated to the rank of full genus. Thetype specimenmeasures 75 cm (30 in) long and was collected 24–35 km (15–22 mi) away from the mouth of the Umvoti River inSouth Africa.[2][3]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The range of the balloon shark is likely restricted to the waters off theSouth African provinceofKwaZulu-NatalandMozambique.Additional records from theGulf of Adenand offVietnamappear to represent different, yet-undescribed species. This common,bottom-dwellingshark inhabits thecontinental shelfand uppercontinental slope,at depths of 40–600 m (130–1,970 ft). It favors sandy and muddysubstrates.[1][4]There appears to be geographical and/or depth segregation by age: generally only juveniles are found off KwaZulu-Natal at depths of 40–440 m (130–1,440 ft), suggesting that most adults may be found in deeper and/or more northerly waters.[3]

Description

[edit]Reaching 1.1 m (3.6 ft) long, the balloon shark has a stout, firm body and a broad, flattened head. The snout is short and rounded, with each nostril divided by a narrow lobe on its anterior rim. The horizontally oval eyes are equipped with rudimentarynictitating membranes(protective third eyelids) and placed rather high on the head. Above and below each eye are ridges, and behind is a smallspiracle.The capacious mouth forms a wide arch and lacks furrows at the corners; the upper teeth are exposed when the mouth is closed.[3]There are around 60 upper and 44 lower tooth rows; each tooth has a strong central cusp flanked on either side by 1–2 tiny cusplets. Of the five pairs ofgill slits,the third pair is the longest.[3][5]

The firstdorsal finis positioned about opposite thepelvic fins;the second dorsal fin is much smaller and placed opposite theanal fin.Thepectoral finsare large and broad. The pelvic fins are low; adult males have rather short, thickclaspers.The anal fin is smaller than the first dorsal fin but much larger than the second, and is relatively deep. The tail is short, with a deepcaudal finthat bears a small lower lobe and a ventral notch near the tip of the upper lobe. The skin is thick and roughened by well-calcifieddermal denticles;each denticle is triangular and pointed. This species is light grayish brown to purplish above, including the upper surface of the pectoral fins, and paler below. A series of 6–7 faint darker saddles are present along the back and tail, which are more obvious in younger sharks. The fins lack obvious lighter margins.[3][6]

Biology and ecology

[edit]Like other members of its genus, the balloon shark is capable of greatly inflating itsstomachwith water or air as a defense mechanism.[5]A juvenile 48 cm (19 in) long has been found in the stomach of acoelacanth(Latimeria chalumnae).[7]The diet of the balloon shark consists mainly oflobsters,shrimps,andcephalopods,whilebony fishesand otherelasmobranchsmay also be consumed. It isoviparous,with females producingencapsulated eggstwo at a time, one peroviduct.Deposited eggs have yet to be recovered, implying that spawning occurs in deeper and/or more northerly waters that are frequented by the adults.[3][6]Young sharks hatch at roughly 20–22 cm (7.9–8.7 in) long; both sexesmatureat approximately 70–75 cm (28–30 in) long.[4]

Human interactions

[edit]The balloon shark has almost no economic value, though the skin may be utilized. It is regularlycaught incidentallyand discarded bycommercialbottom trawlersoperating in parts of its range, though its population does not yet appear to have been negatively impacted. As a result, theInternational Union for Conservation of Nature(IUCN) has listed this shark under near threatened, while recommending that relevantfisheriesbe carefully monitored.[1]

References

[edit]- ^abcPollom, R.; Bennett, R.; Ebert, D.A.; Fennessy, S.; Fernando, S.; Gledhill, K. (2020)."Cephaloscyllium sufflans".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2020:e.T44606A124434871.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T44606A124434871.en.Retrieved19 November2021.

- ^Regan, C.T. (May 1, 1921)."New fishes from deep water off the coast of Natal"(PDF).Annals and Magazine of Natural History.7(41): 412–420.doi:10.1080/00222932108632540.

- ^abcdefCompagno, L.J.V. (1984).Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date.Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 302–303.ISBN92-5-101384-5.

- ^abCompagno, L.J.V.; M. Dando & S. Fowler (2005).Sharks of the World.Princeton University Press. p. 218.ISBN978-0-691-12072-0.

- ^abFowler, H.W. (1935). "South African Fishes Received from Mr. H. W. Bell-Marley in 1935".Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.87:361–408.

- ^abSmith, J.L.B.; M.M. Smith & P.C. Heemstra (2003).Smiths' Sea fishes.Struik. p. 89.ISBN1-86872-890-0.

- ^Uyeno T. & T. Tsutsumi (1991). "Stomach contents ofLatimeria chalumnaeand further notes on its feeding habits ".Environmental Biology of Fishes.32(1–4): 275–279.doi:10.1007/bf00007460.