Bilateria

| Bilaterians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bilaterian diversity | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria Hatschek,1888 |

| Subdivisions | |

| Synonyms | |

|

TriploblastsLankester, 1873 | |

Bilateria(/ˌbaɪləˈtɪəriə/BY-lə-TEER-ee-ə)[2]is a largecladeorinfrakingdomofanimalscalledbilaterians(/ˌbaɪləˈtɪəriən/BY-lə-TEER-ee-ən),[3]characterized bybilateral symmetry(i.e. having a left and a right side that aremirror imagesof each other) duringembryonic development.This means theirbody plansare laid around a longitudinal axis (rostral–caudalaxis) with a front (or "head" ) and a rear (or "tail" ) end, as well as a left–right–symmetrical belly (ventral) and back (dorsal) surface.[4]Nearly all bilaterians maintain a bilaterally symmetrical body as adults; the most notable exception is theechinoderms,which extend topentaradial symmetryas adults, but are only bilaterally symmetrical as anembryo.Cephalizationis also a characteristic feature among most bilaterians, where thespecial senseorgans andcentral nervegangliabecome concentrated at the front/rostral end.

Bilaterians constitute one of the five mainmetazoanlineages, the other four beingPorifera(sponges),Cnidaria(jellyfish,hydrae,sea anemonesandcorals),Ctenophora(comb jellies) andPlacozoa(tiny "flat animals" ). For the most part, bilateral embryos aretriploblastic,having threegerm layers:endoderm,mesodermandectoderm.Except for a few phyla (i.e.flatwormsandgnathostomulids), bilaterians have completedigestive tractswith a separatemouthandanus.Some bilaterians lackbody cavities(acoelomates,i.e.Platyhelminthes,GastrotrichaandGnathostomulida), while others display primary body cavities (deriving from theblastocoel,aspseudocoeloms) or secondary cavities (that appearde novo,for example thecoelom).

Body plan

[edit]

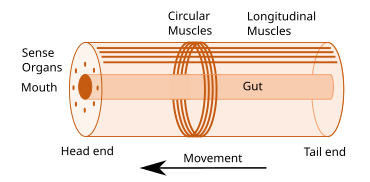

Some of the earliest bilaterians were wormlike, and a bilaterian body can be conceptualized as a cylinder with a gut running between two openings, the mouth and the anus. Around the gut it has an internal body cavity, acoelomor pseudocoelom.[a]Animals with this bilaterally symmetricbody planhave a head (anterior) end and a tail (posterior) end as well as a back (dorsal) and a belly (ventral); therefore they also have a left side and a right side.[6][4]

Having a front end means that this part of the body encounters stimuli, such as food, favouringcephalisation,the development of a head withsense organsand a mouth.[7]The body stretches back from the head, and many bilaterians have a combination of circularmusclesthat constrict the body, making it longer, and an opposing set of longitudinal muscles, that shorten the body;[4]these enable soft-bodied animals with ahydrostatic skeletonto move byperistalsis.[8]Most bilaterians (Nephrozoans) have a gut that extends through the body from mouth to anus, while Xenacoelomorphs have a bag gut with one opening. Many bilaterian phyla have primarylarvaewhich swim withciliaand have an apical organ containing sensory cells. However, there are exceptions to each of these characteristics; for example, adult echinoderms are radially symmetric (unlike their larvae), and certainparasitic wormshave extremelyplesiomorphicbody structures.[6][4]

Evolution

[edit]

The hypotheticalmost recent common ancestorof all bilateria is termed the "Urbilaterian".[10][11]The nature of the first bilaterian is a matter of debate. One side suggests that acoelomates gave rise to the other groups (planuloid–aceloid hypothesis byLudwig von Graff,Elie Metchnikoff,Libbie Hyman,orLuitfried von Salvini-Plawen), while the other poses that the first bilaterian was a coelomate organism and the main acoelomate phyla (flatwormsandgastrotrichs) have lost body cavities secondarily (the Archicoelomata hypothesis and its variations such as the Gastrea byHaeckelorSedgwick,the Bilaterosgastrea byGösta Jägersten,or the Trochaea by Nielsen).

One hypothesis is that the original bilaterian was a bottom dwelling worm with a single body opening, similar toXenoturbella.[5]Alternatively, it may have resembled the planula larvae of some cnidaria, which have some bilateral symmetry.[12]However, there is evidence that it was segmented, as the mechanism for creating segments is shared between vertebrates (deuterostomes) and arthropods (protostomes).[13]

Fossil record

[edit]The first evidence of bilateria in the fossil record comes from trace fossils inEdiacaransediments, and the firstbona fidebilaterian fossil isKimberella,dating to555million years ago.[14]Earlier fossils are controversial; the fossilVernanimalculamay be the earliest known bilaterian, but may also represent an infilled bubble.[15][16]Fossil embryosare known from around the time ofVernanimalcula(580million years ago), but none of these have bilaterian affinities.[17]Burrows believed to have been created by bilaterian life forms have been found in theTacuarí Formationof Uruguay, and were believed to be at least 585 million years old.[18]However, more recent evidence shows these fossils are actually late Paleozoic instead of Ediacaran.[19]

Phylogeny

[edit]The Bilateria has traditionally been divided into two main lineages orsuperphyla.[20]Thedeuterostomestraditionally include theechinoderms,hemichordates,chordates,and the extinctVetulicolia.Theprotostomesinclude most of the rest, such asarthropods,annelids,mollusks,flatworms,and so forth. There are several differences, most notably in how theembryodevelops. In particular, the first opening of the embryo becomes the mouth in protostomes, and the anus in deuterostomes. Manytaxonomistsnow recognize at least two more superphyla among the protostomes,Ecdysozoa[21](molting animals) andSpiralia.[21][22][23][24]The arrow worms (Chaetognatha) have proven difficult to classify; recent studies place them in thegnathifera.[25][26][27]

The traditional division of Bilateria intoDeuterostomiaandProtostomiawas challenged when new morphological and molecular evidence found support for a sister relationship between the acoelomate taxa,AcoelaandNemertodermatida(together calledAcoelomorpha), and the remaining bilaterians.[20]The latter clade was calledNephrozoaby Jondelius et al. (2002) andEubilateriaby Baguña and Riutort (2004).[20]The acoelomorph taxa had previously been considered flatworms with secondarily lost characteristics, but the new relationship suggested that the simple acoelomate worm form was the original bilaterian bodyplan and that the coelom, the digestive tract, excretory organs, and nerve cords developed in the Nephrozoa.[20][28]Subsequently the acoelomorphs were placed in phylumXenacoelomorpha,together with thexenoturbellids,and the sister relationship between Xenacoelomorpha and Nephrozoa confirmed in phylogenomic analyses.[28]

A modern consensusphylogenetic treefor Bilateria is shown below, although the positions of certaincladesare still controversial (dashed lines) and the tree has changed considerably since 2000.[29][27][30][31][32]

| ParaHoxozoa |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A different hypothesis is that the Ambulacraria are sister to Xenacoelomorpha together forming theXenambulacraria.The Xenambulacraria may be sister to the Chordata or to theCentroneuralia(corresponding to Nephrozoa without Ambulacraria, or to Chordata + Protostomia). The phylogenetic tree shown below depicts the latter proposal. Also, the validity of Deuterostomia (without Protostomia emerging from it) is under discussion.[33]The cladogram indicates approximately when some clades radiated into newer clades, in millions of years ago (Mya).[34]While the below tree depictsChordataas asister grouptoProtostomiaaccording to analyses by Philippe et al., the authors nonetheless caution that "the support values are very low, meaning there is no solid evidence to refute the traditional protostome and deuterostome dichotomy".[35]

| ParaHoxozoa |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Grazhdankin, Dima (2004)."Patterns of distribution in the Ediacaran biotas: facies versus biogeography and evolution"(PDF).Paleobiology.30(2): 203–221.doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0203:PODITE>2.0.CO;2.S2CID129376371.

- ^"bilateria".Merriam-Webster Dictionary.Retrieved2024-05-12.

- ^"bilaterian".Merriam-Webster Dictionary.Retrieved2024-05-12.

- ^abcdBrusca, Richard C. (2016)."Introduction to the Bilateria and the Phylum Xenacoelomorpha: Triploblasty and Bilateral Symmetry Provide New Avenues for Animal Radiation"(PDF).Invertebrates.Sinauer Associates. pp. 345–372.ISBN978-1-60535-375-3.

- ^abCannon, Johanna Taylor; Vellutini, Bruno Cossermelli; Smith, Julian; Ronquist, Fredrik; Jondelius, Ulf; Hejnol, Andreas (2016)."Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa".Nature.530(7588): 89–93.Bibcode:2016Natur.530...89C.doi:10.1038/nature16520.PMID26842059.S2CID205247296.

- ^abMinelli, Alessandro (2009).Perspectives in Animal Phylogeny and Evolution.Oxford University Press. p. 53.ISBN978-0-19-856620-5.

- ^Finnerty, John R. (November 2005)."Did internal transport, rather than directed locomotion, favor the evolution of bilateral symmetry in animals?"(PDF).BioEssays.27(11): 1174–1180.doi:10.1002/bies.20299.PMID16237677.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2019-07-02.Retrieved2018-03-07.

- ^Quillin, K. J. (May 1998)."Ontogenetic scaling of hydrostatic skeletons: geometric, static stress and dynamic stress scaling of the earthworm lumbricus terrestris".The Journal of Experimental Biology.201(12): 1871–83.doi:10.1242/jeb.201.12.1871.PMID9600869.

- ^Evans, Scott D.; Hughes, Ian V.; Gehling, James G.; Droser, Mary L. (7 April 2020)."Discovery of the oldest bilaterian from the Ediacaran of South Australia".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.117(14): 7845–7850.Bibcode:2020PNAS..117.7845E.doi:10.1073/pnas.2001045117.ISSN0027-8424.PMC7149385.PMID32205432.

- ^Knoll, Andrew H.;Carroll, Sean B.(25 June 1999). "Early Animal Evolution: Emerging Views from Comparative Biology and Geology".Science.284(5423): 2129–2137.doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2129.PMID10381872.S2CID8908451.

- ^Balavoine, G.; Adoutte, Andre (2003). "The segmented Urbilateria: A testable scenario".Integrative and Comparative Biology.43(1): 137–147.CiteSeerX10.1.1.560.8727.doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.137.PMID21680418.S2CID80975506.

- ^Baguñà, Jaume; Martinez, Pere; Paps, Jordi; Riutort, Marta (April 2008)."Back in time: a new systematic proposal for the Bilateria".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.363(1496): 1481–1491.doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2238.PMC2615819.PMID18192186.

- ^Held, Lewis I.(2014).How the Snake Lost its Legs. Curious Tales from the Frontier of Evo-Devo.Cambridge University Press.p. 11.ISBN978-1-107-62139-8.

- ^Fedonkin, M. A.; Waggoner, B. M. (November 1997)."The Late Precambrian fossil Kimberella is a mollusc-like bilaterian organism".Nature.388(6645): 868–871.Bibcode:1997Natur.388..868F.doi:10.1038/42242.S2CID4395089.

- ^Bengtson, S.; Budd, G. (19 November 2004)."Comment on 'small bilaterian fossils from 40 to 55 million years before the Cambrian'".Science.306(5700): 1291a.doi:10.1126/science.1101338.PMID15550644.

- ^Bengtson, S.; Donoghue, P. C. J.; Cunningham, J. A.; Yin, C. (2012)."A merciful death for the 'earliest bilaterian,' Vernanimalcula".Evolution & Development.14(5): 421–427.doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2012.00562.x.PMID22947315.S2CID205675058.

- ^Hagadorn, J. W.; Xiao, S.; Donoghue, P. C. J.; Bengtson, S.; Gostling, N. J.; Pawlowska, M.; Raff, E. C.; Raff, R. A.; Turner, F. R.; Chongyu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, X.; McFeely, M. B.; Stampanoni, M.; Nealson, K. H. (13 October 2006). "Cellular and Subcellular Structure of Neoproterozoic Animal Embryos".Science.314(5797): 291–294.Bibcode:2006Sci...314..291H.doi:10.1126/science.1133129.PMID17038620.S2CID25112751.

- ^Pecoits, E.; Konhauser, K. O.; Aubet, N. R.; Heaman, L. M.; Veroslavsky, G.; Stern, R. A.; Gingras, M. K. (June 29, 2012). "Bilaterian burrows and grazing behavior at >585 million years ago".Science.336(6089): 1693–1696.Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1693P.doi:10.1126/science.1216295.PMID22745427.S2CID27970523.

- ^Verde, Mariano (15 September 2022)."Revisiting the supposed oldest bilaterian trace fossils from Uruguay: Late Paleozoic, not Ediacaran".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.602.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111158.

- ^abcdNielsen, Claus (2008). "Six major steps in animal evolution: are we derived sponge larvae?".Evol. Dev.10(2): 241–257.doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00231.x.PMID18315817.S2CID8531859.

- ^abHalanych, K.; Bacheller, J.; Aguinaldo, A.; Liva, S.; Hillis, D.; Lake, J. (17 March 1995). "Evidence from 18S ribosomal DNA that the lophophorates are protostome animals".Science.267(5204): 1641–1643.Bibcode:1995Sci...267.1641H.doi:10.1126/science.7886451.PMID7886451.S2CID12196991.

- ^Paps, J.; Baguna, J.; Riutort, M. (14 July 2009)."Bilaterian phylogeny: a broad sampling of 13 nuclear genes provides a new Lophotrochozoa phylogeny and supports a paraphyletic basal Acoelomorpha".Molecular Biology and Evolution.26(10): 2397–2406.doi:10.1093/molbev/msp150.PMID19602542.

- ^Telford, Maximilian J. (15 April 2008)."Resolving animal phylogeny: A sledgehammer for a tough nut?".Developmental Cell.14(4): 457–459.doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.016.PMID18410719.

- ^Kimball, John W.(3 March 2010)."The Invertebrate Animals"(online biology textbook). Kimball's Biology Pages. Archived fromthe originalon 2010-03-10.Retrieved2006-01-09.

- abbridged byauthorfrom

- ^Helfenbein, Kevin G.; Fourcade, H. Matthew; Vanjani, Rohit G.; Boore, Jeffrey L. (20 July 2004)."The mitochondrial genome ofParaspadella gotoiis highly reduced and reveals that chaetognaths are a sister group to protostomes ".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.101(29): 10639–10643.Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110639H.doi:10.1073/pnas.0400941101.PMC489987.PMID15249679.

- ^Papillon, Daniel; Perez, Yvan; Caubit, Xavier; Yannick Le, Parco (November 2004)."Identification of chaetognaths as protostomes is supported by the analysis of their mitochondrial genome".Molecular Biology and Evolution.21(11): 2122–2129.doi:10.1093/molbev/msh229.PMID15306659.

- ^abFröbius, Andreas C.; Funch, Peter (2017-04-04)."Rotiferan Hox genes give new insights into the evolution of metazoan bodyplans".Nature Communications.8(1): 9.Bibcode:2017NatCo...8....9F.doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w.PMC5431905.PMID28377584.

- ^abCannon, Johanna Taylor; Vellutini, Bruno Cossermelli; Smith, Julian; Ronquist, Fredrik; Jondelius, Ulf; Hejnol, Andreas (2016)."Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa".Nature.530(7588): 89–93.Bibcode:2016Natur.530...89C.doi:10.1038/nature16520.PMID26842059.S2CID205247296.

- ^Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Giribet, Gonzalo; Dunn, Casey W.; Hejnol, Andreas; Kristensen, Reinhardt M.; Neves, Ricardo C.; et al. (June 2011)."Higher-level metazoan relationships: recent progress and remaining questions".Organisms, Diversity & Evolution.11(2): 151–172.doi:10.1007/s13127-011-0044-4.S2CID32169826.

- ^Smith, Martin R.; Ortega-Hernández, Javier (2014)."Hallucigenia's onychophoran-like claws and the case for Tactopoda"(PDF).Nature.514(7522): 363–366.Bibcode:2014Natur.514..363S.doi:10.1038/nature13576.PMID25132546.S2CID205239797.

- ^"Ecdysozoa".Metazoa.Palaeos (palaeos ).Retrieved2017-09-02.

- ^Yamasaki, Hiroshi; Fujimoto, Shinta; Miyazaki, Katsumi (June 2015)."Phylogenetic position of Loricifera inferred from nearly complete 18S and 28S rRNA gene sequences".Zoological Letters.1:18.doi:10.1186/s40851-015-0017-0.PMC4657359.PMID26605063.

- ^Kapli, Paschalia; Natsidis, Paschalis; Leite, Daniel J.; Fursman, Maximilian; Jeffrie, Nadia; Rahman, Imran A.; et al. (2021-03-19)."Lack of support for Deuterostomia prompts reinterpretation of the first Bilateria".Science Advances.7(12): eabe2741.Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2741K.doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe2741.ISSN2375-2548.PMC7978419.PMID33741592.

- ^Peterson, Kevin J.; Cotton, James A.; Gehling, James G.; Pisani, Davide (27 April 2008)."The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences.363(1496): 1435–1443.doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233.PMC2614224.PMID18192191.

- ^Philippe, Hervé; Poustka, Albert J.; Chiodin, Marta; Hoff, Katharina J.; Dessimoz, Christophe; Tomiczek, Bartlomiej; et al. (2019). "Mitigating anticipated effects of systematic errors supports sister-group relationship between Xenacoelomorpha and Ambulacraria".Current Biology.29(11): 1818–1826.e6.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.009.hdl:21.11116/0000-0004-DC4B-1.ISSN0960-9822.PMID31104936.S2CID155104811.