Blue cheese

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(March 2011) |

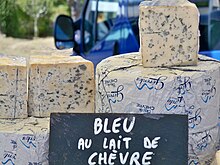

Blue cheese[a]is any of a wide range ofcheesesmade with the addition ofculturesof ediblemolds,which create blue-green spots or veins through the cheese. Blue cheeses vary in taste from very mild to strong, and from slightly sweet to salty or sharp; in colour from pale to dark; and in consistency from liquid to hard. They may have a distinctive smell, either from the mold or from various specially cultivated bacteria such asBrevibacterium linens.[1]

Some blue cheeses are injected withsporesbefore thecurdsform, and others have spores mixed in with the curds after they form. Blue cheeses are typically aged in temperature-controlled environments.

History

[edit]Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident when cheeses were stored in caves with naturally controlled temperature and moisture levels which happened to be favorable environments for varieties of harmless mold.[2]Analysis ofpaleofecessampled in thesalt minesofHallstatt(Austria) showed that miners of theHallstatt Period(800 to 400 BC) already consumed blue cheese and beer.[3]

According to legend, one of the first blue cheeses,Roquefort,was discovered when a young boy, eating bread andewes' milkcheese, abandoned his meal in a nearby cave after seeing a beautiful girl in the distance. When he returned months later, the mold (Penicillium roqueforti) had transformed his cheese into Roquefort.[4][5]

Gorgonzolais one of the oldest known blue cheeses, having been created around AD 879, though it is said that it did not contain blue veins until around the 11th century.[6][7]Stiltonis a relatively new addition, becoming popular sometime in the early 1700s.[8]Many varieties of blue cheese originated subsequently, such as the 20th centuryDanabluandCambozola,were an attempt to fill the demand for Roquefort-style cheeses.

Production

[edit]Similarly to other varieties of cheese, the process of making blue cheese consists of six standard steps. However, additional ingredients and processes are required to give this blue-veined cheese its particular properties. To begin with, the commercial scale production of blue cheese consists of two phases: the culturing of suitable spore-rich inocula and fermentation for maximum, typical flavor.[9]

Penicillium roquefortiinoculum

[edit]This sectionis missing informationabout Penicillium glaucum.(October 2023) |

In the first phase of production, aPenicillium roquefortiinoculum is prepared prior to the actual production of blue cheese.[10]Multiple methods can be used to achieve this. However, all methods involve the use of afreeze-driedPenicillium roqueforticulture. AlthoughPenicillium roquefortican be found naturally, cheese producers nowadays use commercially manufacturedPenicillium roqueforti.First,Penicillium roquefortiis washed from a pure culture agar plates which is later frozen.[10]Through the freeze drying process, water from the frozen state is evaporated without the transition through the liquid state (sublimation). This retains the value of the culture and is activated upon the addition of water.

Salt, sugar or both are added toautoclaved,homogenizedmilkvia a sterile solution. This mixture is then inoculated withPenicillium roqueforti.This solution is first incubated for three to four days at 21–25 °C (70–77 °F). More salt and/or sugar is added and then aerobic incubation is continued for an additional one to two days.[9]Alternatively, sterilized, homogenized milk and reconstituted non-fat solids or whey solids are mixed with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium. A spore-richPenicillium roqueforticulture is then added. Next, modified milk fat is added which consists of milk fat with calf pre-gastricesterase.[11]This solution is prepared in advance by an enzyme hydrolysis of a milk fat emulsion. The addition of modified milk fat stimulates a progressive release of free fatty acids via lipase action which is essential for rapid flavor development in blue cheese.[10]This inoculum produced by either methods is later added to the cheese curds.[10]

Production and fermentation

[edit]First, raw milk (either from cattle, goats or sheep) is mixed andpasteurizedat 72 °C (162 °F) for 15 seconds.[12]Then, acidification occurs: astarter culture,such asStreptococcus lactis,is added in order to changelactosetolactic acid,thus changing the acidity of the milk and turning it from liquid to solid.[13]The next step iscoagulation,whererennet,a mixture ofrenninand other material found in the stomach lining of a calf is added to solidify the milk further.[13]Following this, thick curds are cut typically with a knife to encourage the release of liquid orwhey.[13]The smaller the curds are cut, the thicker and harder the resulting cheese will become.[13]

After the curds have been ladled into containers in order to be drained and formed into a full wheel of cheese, thePenicillium roquefortiinoculum is sprinkled on top of the curds along withBrevibacterium linens.[13]Then, the curds granules are knit in molds to form cheese loaves with a relatively open texture.[10]Next, whey drainage continues for 10–48 hours in which no pressure is applied, but the molds are inverted frequently to promote this process.[12]Saltis then added to provide flavor as well as to act as a preservative so the cheese does not spoil through the process ofbrine saltingor dry salting for 24–48 hours.[12]The final step is ripening the cheese by aging it. When the cheese is freshly made, there is little to no blue cheese flavor development.[10]Usually, a fermentation period of 60–90 days are needed before the flavor of the cheese is typical and acceptable for marketing.[10]

During this ripening period, the temperature and the level of humidity in the room where the cheese is aging is monitored to ensure the cheese does not spoil or lose its optimal flavor and texture.[13]In general, the ripening temperature is around eight to ten degrees Celsius with a relative humidity of 85–95%, but this may differ according to the type of blue cheese being produced.[12]At the beginning of this ripening process, the cheese loaves are punctured to create small openings to allow air to penetrate and support the rich growth of the aerobicPenicillium roqueforticultures, thus encouraging the formation of blue veins.[13]

Throughout the ripening process, the total ketone content is constantly monitored as the distinctive flavor and aroma of blue cheese arises from methylketones(including2-pentanone,2-heptanone,and2-nonanone)[14]which are a metabolic product ofPenicillium roqueforti.[15][16]

Toxins from the production of blue cheese

[edit]Penicillium roqueforti,responsible for the greenish blue moldy aspect of blue cheese, produces severalmycotoxins.While mycotoxins likeroquefortine,isofumigaclavine A,mycophenolic acidandferrichromeare present at low levels,penicillic acidandPR toxinare unstable in the cheese. Because of the instability of PR toxin and lack of optimal environmental conditions (temperature, aeration) for the production of PR toxin and roquefortine, health hazards due toPenicillium roquefortimetabolitesare considerably reduced.[17]Additionally, mycotoxin contamination occurs at low levels and large quantities of cheese are rarely consumed, suggesting that hazard to human health is unlikely.[18]

Physicochemical properties

[edit]Structure

[edit]The main structure of the blue cheese comes from the aggregation of thecasein.Inmilk,casein does not aggregate because of the outer layer of the particle, called the “hairy layer.” The hairy layer consists of κ-casein, which are strings ofpolypeptidesthat extend outward from the center of the caseinmicelle.[19]The entanglement of the hairy layer between casein micelles decreases theentropyof the system because it constrains the micelles, preventing them from spreading out. Curds form, however, due to the function that theenzyme,rennet, plays in removing the hairy layer in the casein micelle.Rennetis an enzyme that cleaves the κ-casein off the casein micelle, thus removing the strain that occurs when the hairy layer entangles. The casein micelles are then able to aggregate together when they collide with each other, forming the curds that can then be made into blue cheese.

Mold growth

[edit]Penicillium roquefortiandPenicillium glaucumare both molds that require the presence of oxygen to grow. Therefore, initial fermentation of the cheese is done bylactic acid bacteria.The lactic acid bacteria, however, are killed by the lowpHand the secondary fermenters,Penicillium roqueforti,take over and break the lactic acid down, maintaining a pH in the aged cheese above 6.0.[20]As the pH rises again from the loss oflactic acid,the enzymes in the molds responsible forlipolysisandproteolysisare more active and can continue to ferment the cheese because they are optimal at a pH of 6.0.[21]

Penicillium roqueforticreates the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese after the aged curds have been pierced, forming air tunnels in the cheese.[22]When given oxygen, the mold is able to grow along the surface of the curd-air interface.[23]The veins along the blue cheese are also responsible for the aroma of blue cheese itself. In fact, one type of bacteria in blue cheese,Brevibacterium linens,is the same bacteria responsible for foot and body odor.B. linenswas previously thought to give cheeses their distinct orangish pigmentation, but studies show this not to be the case and blue cheese is an example of the lack of that orange pigmentation.[24]In pressing the cheese, the curds are not tightly packed in order to allow for air gaps between them. After piercing, the mold can also grow in between the curds.

Flavour

[edit]A portion of the distinctflavourcomes fromlipolysis(breakdown of fat). The metabolism of the blue mold further breaks down fatty acids to form ketones to give blue cheese a richer flavour and aroma.[25]

Regulation

[edit]European Union

[edit]In theEuropean Union,many blue cheeses, such asCabrales,Danablu,Gorgonzola,RoquefortandBlue Stilton,carry aprotected designation of origin,meaning they can bear the name only if they have been made in a particular region. Similarly, individual countries have protections of their own such as France'sAppellation d'Origine Contrôléeand Italy'sDenominazione di Origine Protetta.Blue cheeses with no protected origin name are designated simply "blue cheese".

Canada

[edit]Under the regulation of theCanadian Food Inspection Agency,manufacturers can produce blue cheese with a maximum of 47 percent moisture and minimum of 27 percent milk fat.[26]Salt is allowed to be used as a preservative; however, the amount of the salt or combination of salts shall not exceed 200 parts per million of milk and milk products used to make the cheese.[26]The Canadian Food Inspection Agency does not limit the use of bacterial cultures to aid further ripening and flavoring preparations other than cheese flavoring.[26]

United States

[edit]The United StatesCode of Federal Regulationsstandard for blue cheese specifies a minimum milkfat content of 50 percent, and maximum moisture of 46 percent.[27]Optional ingredients permitted include food coloring to neutralize the yellowish tint of the cheese,benzoyl peroxidebleach, and vegetable wax for coating the rind.

Properties

[edit]Gorgonzola, Stilton, and Roquefort are considered to be favored blue cheeses in many countries.[28]These cheeses all have aprotected designation of originin which they may only be called their respective name if produced a certain way in a certain location.

Gorgonzola

[edit]

Gorgonzola blue cheese takes its name from the village ofGorgonzolain Italy where it was first made.[28]Belonging to the family ofStracchinocheeses, Gorgonzola is a whole milk, white, and "uncooked" cheese.[28]This blue cheese is inoculated withPenicillium glaucumwhich, during ripening, produces the characteristic of blue-green veins.[28]The odor of Gorgonzola varies between natural and creamy Gorgonzola.[29][30]63 components in natural Gorgonzola cheese and 52 components in creamy Gorgonzola cheese contribute to odor with 2-nonanone,1-octen-3-ol,2-heptanol,ethyl hexanoate,methylanisoleand2-heptanonebeing the prominent compounds for odor in both cheeses.[29][31]

Stilton

[edit]

Stilton blue cheese was first sold in the village ofStiltonin England but there is little evidence it was ever made there. Different fromStichelton,which is made from raw milk, Stilton cheese is made frompasteurized milk.[28]In addition to being inoculated withPenicillium roquefortito give it the blue vein characteristic, research has shown that other microbiota which are relatives ofLactococcus lactis,Enterococcus faecalis,Lactobacillus plantarum,Lactobacillus curvatus,Leuconostoc mesenteroides,Staphylococcus equorum,andStaphylococcussp.can also be found in Stilton cheese.[32]Some important microbiota contribute to the aromatic profile such as those of theLactobacillusgenus due to their production ofvolatile compounds.[33]During ripening,free fatty acidsincrease in amount which contribute to the characteristic flavor of blue cheeses due tofat breakdownbyPenicillium roqueforti.[34]

Roquefort

[edit]

Roquefort blue cheese originates from the village ofRoquefort-sur-Soulzon,France.[28]Its flavors come from the use of unpasteurizedsheep's milk,inoculation withPenicillium roqueforti,and the special conditions of the natural caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon in which they are ripened.[28]Penicillium roquefortiis the cause of the blue veins in Roquefort cheese. In addition toPenicillium roqueforti,various yeasts are present, namelyDebaryomyces hanseniiand its non-sporulating formCandida famata,andKluyveromyces lactisand its non-sporulating formCandida sphaerica.[35]Similarly to other kinds of blue cheeses, Roquefort's flavor and odor can be attributed to the particular mixture of methyl ketones such as 2-heptanone,2-pentanone,and 2-nonanone.[14]

See also

[edit]Gallery

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Deetae P; Bonnarme P; Spinnler HE; Helinck S (October 2007). "Production of volatile aroma compounds by bacterial strains isolated from different surface-ripened French cheeses".Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.76(5): 1161–71.doi:10.1007/s00253-007-1095-5.PMID17701035.S2CID24495569.

- ^Cantor, M.D.; Van Den Tempel, T.; Hansen, T.K.; Ardö, Y. (1 January 2004)."Blue cheese".Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology.2:175–198.doi:10.1016/S1874-558X(04)80044-7.ISBN9780122636530.ISSN1874-558X.

- ^Maixner, Frank, et al. (2021)."Hallstatt miners consumed blue cheese and beer during the Iron Age and retained a non-Westernized gut microbiome until the Baroque period".Current Biology.31(23): 5149–5162.e6.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.09.031.PMC8660109.PMID34648730.S2CID238754581.

- ^Fabricant, Florence (23 June 1982)."Blue-veined Cheeses: The expanding choices".The New York Times.Retrieved22 May2010.

- ^"Something is rotten in Roquefort".Business Week.31 December 2001.

- ^"Gorgonzola, the cheese that lives".Italian Food Excellence.30 September 2013.Retrieved7 August2016.

- ^"Castello® Gorgonzola".Castello.Retrieved7 August2016.

- ^"History of Stilton".StiltonCheese.co.uk.Archived fromthe originalon 7 August 2016.Retrieved7 August2016.

- ^abWatts, j. C. Jr.. Nelson, J. H. (to Dairyland Food Laboratories, Inc.), U.S. Patent 3,072,488 (8 January 1963).

- ^abcdefgNelson, John Howard. (July 1970). "Production of Blue cheese flavor via submerged fermentation by Penicillium roqueforti".Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.18(4): 567–569.doi:10.1021/jf60170a024.

- ^Nelson, J.H.; Jensen, R.G.; Pitas, R.E. (March 1977)."Pregastric Esterase and other Oral Lipases—A Review".Journal of Dairy Science.60(3): 327–362.doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(77)83873-3.PMID321489.

- ^abcdCantor, M. D.; van den Tempel, T.; Hansen, T. K.; Ardö, Y. (2004). "Blue cheese".Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology.Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 175–198.doi:10.1016/S1874-558X(04)80044-7.ISBN9780122636530.

- ^abcdefg"What Makes Blue Cheese Blue?".The Spruce.Archived fromthe originalon 14 January 2017.Retrieved13 November2017.

- ^abPatton, Stuart (September 1950)."The Methyl Ketones of Blue Cheese and their Relation to its Flavor".Journal of Dairy Science.33(9): 680–684.doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(50)91954-0.

- ^"Methyl ketones: Butter".webexhibits.org..

- ^Harte, Bruce R.; Stine, C.M. (August 1977)."Effects of Process Parameters on Formation of Volatile Acids and Free Fatty Acids in Quick-Ripened Blue Cheese".Journal of Dairy Science.60(8): 1266–1272.doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(77)84021-6.

- ^Medina, Margarita; Gaya, Pilar; Nuñez, M. (February 1985)."Production of PR Toxin and Roquefortine by Penicillium roqueforti Isolates from Cabrales Blue Cheese".Journal of Food Protection.48(2): 118–121.doi:10.4315/0362-028X-48.2.118.PMID30934519.

- ^Dobson, Alan D. W. (2017). "Mycotoxins in Cheese".Cheese(4th ed.). Academic Press. pp. 595–601.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-417012-4.00023-5.ISBN978-0-12-417012-4.

- ^Shukla, Anuj; Narayanan, Theyencheri; Zanchi, Drazen (2009)."Structure of casein micelles and their complexation with tannins".Soft Matter.5(15): 2884.Bibcode:2009SMat....5.2884S.doi:10.1039/b903103k.Retrieved17 December2017.

- ^Diezhandino; Fernandez; Gonzalez; McSweeney; Fresno (2015). "Microbiological, physio-chemical and proteolytic changes in a Spanish blue cheese during ripening (Valdeon cheese)".Food Chemistry.168(1): 134–141.doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.039.PMID25172692.

- ^Gilliot; Jany; Poirier; Maillard; Debaets; Thierry; Coton; Coton (2017). "Functional diversity within the Penicillium roqueforti species".International Journal of Food Microbiology.241(1): 141–150.doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.10.001.PMID27771579.

- ^Cantor, Mette Dines; van den Tempel, Tatjana; Hansen, Tine Kronborg; Ardö, Ylva (1 January 2017), McSweeney, Paul L. H.; Fox, Patrick F.; Cotter, Paul D.; Everett, David W. (eds.),"Chapter 37 - Blue Cheese",Cheese (Fourth Edition),San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 929–954,ISBN978-0-12-417012-4,retrieved1 February2024

- ^Fernandez-salguero (2004). "INTERNAL MOULD - RIPENED CHEESES: CHARACTERISTICS, COMPOSITION AND PROTEOLYSIS OF THE MAIN EUROPEAN BLUE VEIN VARIETIES".Italian Journal of Food Science.16(4).

- ^Wolfe, Benjamin (27 July 2014)."digesting the science of fermented foods".microbialfoods.org.Retrieved27 July2014.

- ^Polowsky, Pat."Blue".cheesescience.org.

- ^abcBranch, Legislative Services (17 June 2019)."Consolidated federal laws of canada, Food and Drug Regulations".laws-lois.justice.gc.ca.Retrieved5 August2019.

- ^"Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21".US Food and Drug Administration.Retrieved3 May2024.

- ^abcdefgDavidson, Alan; Jaine, Tom (2014).The Oxford Companion to Food (3 ed.).Oxford University Press.ISBN9780199677337.

- ^abAddeo, Francesco; Piombino, Paola; Moio, Luigi (May 2000). "Odour-impact compounds of Gorgonzola cheese".Journal of Dairy Research.67(2): 273–285.doi:10.1017/S0022029900004106.ISSN1469-7629.PMID10840681.

- ^Moio, Luigi; Piombino, Paola; Addeo, Francesco (1 May 2000). "Odour-impact compounds of Gorgonzola cheese".Journal of Dairy Research.67(2): 273–285.doi:10.1017/S0022029900004106.PMID10840681.

- ^Monti, Lucia; Pelizzola, Valeria; Povolo, Milena; Fontana, Stefano; Contarini, Giovanna (August 2019). "Study on the sugar content of blue-veined 'Gorgonzola' PDO cheese".International Dairy Journal.95:1–5.doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2019.03.009.S2CID133493530.

- ^Ercolini, D.; Hill, P. J.; Dodd, C. E. R. (1 June 2003)."Bacterial Community Structure and Location in Stilton Cheese".Applied and Environmental Microbiology.69(6): 3540–3548.Bibcode:2003ApEnM..69.3540E.doi:10.1128/AEM.69.6.3540-3548.2003.PMC161494.PMID12788761.

- ^Mugampoza, Diriisa; Gkatzionis, Konstantinos; Linforth, Robert S.T.; Dodd, Christine E.R. (July 2019)."Acid production, growth kinetics and aroma profiles of Lactobacillus flora from Stilton cheese".Food Chemistry.287:222–231.doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.082.PMID30857693.S2CID75135576.

- ^Madkor, S.; Fox, P.F.; Shalabi, S.I.; Metwalli, N.H. (January 1987). "Studies on the ripening of stilton cheese: Lipolysis".Food Chemistry.25(2): 93–109.doi:10.1016/0308-8146(87)90058-6.

- ^Besançon, X.; Smet, C.; Chabalier, C.; Rivemale, M.; Reverbel, J.P.; Ratomahenina, R.; Galzy, P. (September 1992). "Study of surface yeast flora of Roquefort cheese".International Journal of Food Microbiology.17(1): 9–18.doi:10.1016/0168-1605(92)90014-T.PMID1476870.

- ^A common variant, using the French spelling of "blue";

- ^Oxford English Dictionary,updated 1972,s.v.