Anatomical terms of location

|

| This article is part ofa serieson |

| Anatomical terminology |

|---|

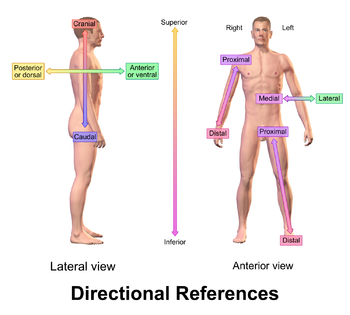

Standardanatomical terms of locationare used to unambiguously describe theanatomyofanimals,includinghumans.The terms, typically derived fromLatinorGreekroots, describe something in itsstandard anatomical position.This position provides a definition of what is at the front ( "anterior" ), behind ( "posterior" ) and so on. As part of defining and describing terms, the body is described through the use ofanatomical planesandanatomical axes.

The meaning of terms that are used can change depending on whether an organism isbipedalorquadrupedal.Additionally, for some animals such asinvertebrates,some terms may not have any meaning at all; for example, an animal that is radially symmetrical will have no anterior surface, but can still have a description that a part is close to the middle ( "proximal" ) or further from the middle ( "distal" ).

International organisations have determined vocabularies that are often used as standards for subdisciplines of anatomy. For example,Terminologia Anatomicafor humans andNomina Anatomica Veterinariafor animals. These allow parties that use anatomical terms, such asanatomists,veterinarians,andmedical doctors,to have a standard set of terms to communicate clearly the position of a structure.

Introduction

[edit]

Standardanatomicalandzoologicalterms of location have been developed, usually based on Latin andGreekwords, to enable all biological and medical scientists,veterinarians,doctorsandanatomiststo precisely delineate and communicate information about animal bodies and their organs, even though the meaning of some of the terms often is context-sensitive.[1][2]Much of this information has been standardised in internationally agreed vocabularies for humans (Terminologia Anatomica)[2]and animals (Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria).[1]

Different terms are used for groups of creatures with different body layouts, such asbipeds(creatures that stand on two feet, such as humans) andquadrupeds.[1]The reasoning is that theneuraxisis different between the two groups, and so is what is considered thestandard anatomical position,such as how humans tend to be standing upright and with their arms reaching forward.[2]Thus, the "top" of a human is the head, whereas the "top" of a dog would be the back, and the "top" of afloundermay be on either the left or right side. Unique terms are also used to describeinvertebratesas well, because of their wider variety of shapes and symmetry.[3]

Standard anatomical position

[edit]

Becauseanimalscan change orientation with respect to their environment, and becauseappendageslikelimbsandtentaclescan change position with respect to the main body, terms to describe position need to refer to an animal when it is in itsstandard anatomical position.[1]This means descriptions as if the organism is in its standard anatomical position, even when the organism in question has appendages in another position. This helps avoid confusion in terminology when referring to the same organism in different postures.[1]In humans, this refers to the body in a standing position with arms at the side and palms facing forward, with thumbs out and to the sides.[2][1]

Combined terms

[edit]

Many anatomical terms can be combined, either to indicate a position in two axes simultaneously or to indicate the direction of a movement relative to the body. For example, "anterolateral" indicates a position that is both anterior and lateral to the body axis (such as the bulk of thepectoralis majormuscle).

Inradiology,anX-rayimage may be said to be "anteroposterior", indicating that the beam of X-rays passes from their source to patient'santeriorbody wall through the body to exit throughposteriorbody wall.[4]Combined terms were once generally hyphenated, but the modern tendency is to omit the hyphen.[5]

Planes

[edit]

Anatomical terms describe structures with relation to four mainanatomical planes:[2]

- Themedian plane,which divides the body into left and right.[2][6]This passes through thehead,spinal cord,navel,and, in many animals, thetail.[6]

- Thesagittal planes,which areparallelto the median plane.[1]

- Thefrontal plane,also called thecoronal plane,which divides the body into front and back.[2]

- Thehorizontal plane,also known as thetransverse plane,which is perpendicular to the other two planes.[2]In a human, this plane is parallel to the ground; in a quadruped, this divides the animal into anterior and posterior sections.[3]

Axes

[edit]

The axes of the body are lines drawn about which an organism is roughly symmetrical.[7]To do this, distinct ends of an organism are chosen, and the axis is named according to those directions. An organism that is symmetrical on both sides has three main axes that intersect atright angles.[3]An organism that is round or not symmetrical may have different axes.[3]Example axes are:

Examples of axes in specific animals are shown below.

-

Anatomical axes in a human, similar for otherorthograde bipedalvertebrates

-

Anatomical axes and directions in afish

Modifiers

[edit]

Several terms are commonly seen and used asprefixes:

- Sub-(fromLatinsub'preposition beneath, close to, nearly etc') is used to indicate something that is beneath, or something that is subordinate to or lesser than.[12]For example,subcutaneousmeans beneath the skin.

- Hypo-(fromAncient Greekὑπό'under') is used to indicate something that is beneath.[13]For example, thehypoglossal nervesupplies the muscles beneath the tongue.

- Infra-(fromLatininfra'under') is used to indicate something that is within or below.[14]For example, theinfraorbital nerveruns within theorbit.

- Inter-(fromLatininter'between') is used to indicate something that is between.[15]For example, theintercostal musclesrun between theribs.

- Super-orSupra-(fromLatinsuper, supra'above, on top of') is used to indicate something that is above something else.[16]For example, thesupraorbital ridgesare above theeyes.

Other terms are used assuffixes,added to the end of words:

- -ad(fromLatinad'towards') and-ab(fromLatinab) are used to indicate that something is towards (-ad) or away from (-ab) something else.[17][18]For example, "distad" means "in the distal direction", and "distad of the femur" means "beyond the femur in the distal direction". Further examples may include cephalad (towards the cephalic end), craniad, and proximad.[19]

Main terms

[edit]

Superior and inferior

[edit]Superior(fromLatinsuper'above') describes what is above something[20]andinferior(fromLatininferus'below') describes what is below it.[21]For example, in theanatomical position,the most superior part of the human body is the head and the most inferior is the feet. As a second example, in humans, theneckis superior to thechestbut inferior to thehead.

Anterior and posterior

[edit]Anterior(fromLatinante'before') describes what is in front,[22]andposterior(fromLatinpost'after') describes what is to the back of something.[23]For example, for a dog thenoseis anterior to the eyes and thetailis considered the most posterior part; for manyfishthegillopenings are posterior to the eyes but anterior to the tail.

Medial and lateral

[edit]These terms describe how close something is to the midline, or the medial plane.[2]Lateral(fromLatinlateralis'to the side') describes something to the sides of an animal, as in "left lateral" and "right lateral".Medial(fromLatinmedius'middle') describes structures close to the midline,[2]or closer to the midline than another structure. For example, in a human, the arms are lateral to thetorso.Thegenitalsare medial to the legs.Temporalhas a similar meaning to lateral but is restricted to the head.

The terms "left" and "right" are sometimes used, or their Latin alternatives (Latin:dexter,lit. 'right';Latin:sinister,lit. 'left'). However, it is preferred to use more precise terms where possible.

Terms derived from lateral include:

- Contralateral(fromLatincontra'against'): on the side opposite to another structure.[24]For example, the right arm and leg are controlled by the left,contralateral, side of the brain.

- Ipsilateral(fromLatinipse'same'): on the same side as another structure.[25]For example, the left arm is ipsilateral to the left leg.

- Bilateral(fromLatinbis'twice'): on both sides of the body.[26]For example, bilateralorchiectomymeans removal oftesteson both sides of the body.

- Unilateral(fromLatinunus'one'): on one side of the body.[27]For example, astrokecan result in unilateralweakness,meaning weakness on one side of the body.

Varus(fromLatin'bow-legged') andvalgus(fromLatin'knock-kneed' ) are terms used to describe a state in which a part further away is abnormally placed towards (varus) or away from (valgus) the midline.[28]

Proximal and distal

[edit]

The termsproximal(fromLatinproximus'nearest') anddistal(fromLatindistare'to stand away from') are used to describe parts of a feature that are close to or distant from the main mass of the body, respectively.[29]Thus the upper arm in humans is proximal and the hand is distal.

"Proximal and distal" are frequently used when describingappendages,such asfins,tentacles,andlimbs.Although the direction indicated by "proximal" and "distal" is always respectively towards or away from the point of attachment, a given structure can be either proximal or distal in relation to another point of reference. Thus the elbow is distal to a wound on the upper arm, but proximal to a wound on the lower arm.[30]

The terms are also applied to internal anatomy, such as to thereproductive tract of snails.Unfortunately, different authors use the terms in opposite senses. Some consider "distal" as further from a point of origin near the centre of the body and others as further from where the organ reaches the body's surface; or other points of origin may be envisaged.[31]

This terminology is also employed in molecular biology and therefore by extension is also used in chemistry, specifically referring to the atomic loci of molecules from the overallmoietyof a given compound.[32]

Central and peripheral

[edit]Centralandperipheralrefer to the distance towards and away from the centre of something.[33]That might be an organ, a region in the body, or an anatomical structure. For example, thecentral nervous systemand theperipheral nervous systems.

Central(fromLatincentralis) describes something close to the centre.[33]For example, thegreat vesselsrun centrally through the body; many smaller vessels branch from these.

Peripheral(fromLatinperipheria,originally fromAncient Greek) describes something further away from the centre of something.[34]For example, the arm is peripheral to the body.

Superficial and deep

[edit]These terms refer to the distance of a structure from the surface.[2]

Deep(fromOld English) describes something further away from the surface of the organism.[35]For example, theexternal oblique muscleof the abdomen is deep to the skin. "Deep" is one of the few anatomical terms of location derived fromOld Englishrather than Latin – the anglicised Latin term would have been "profound" (fromLatinprofundus'due to depth').[1][36]

Superficial(fromLatinsuperficies'surface') describes something near the outer surface of the organism.[1][37]For example, inskin,theepidermisis superficial to thesubcutis.

Dorsal and ventral

[edit]These two terms, used in anatomy andembryology,describe something at the back (dorsal) or front/belly (ventral) of an organism.[2]

Thedorsal(fromLatindorsum'back') surface of an organism refers to the back, or upper side, of an organism. If talking about the skull, the dorsal side is the top.[38]

Theventral(fromLatinventer'belly') surface refers to the front, or lower side, of an organism.[38]

For example, in a fish, thepectoral finsare dorsal to theanal fin,but ventral to thedorsal fin.

Rostral, cranial, and caudal

[edit]

Specific terms exist to describe how close or far something is to the head or tail of an animal. To describe how close to the head of an animal something is, three distinct terms are used:

- Rostral(fromLatinrostrum'beak, nose') describes something situated toward the oral or nasal region, or in the case of the brain, toward the tip of the frontal lobe.[39]

- Cranial(fromGreekκρανίον'skull') orcephalic(fromGreekκεφαλή'head') describes how close something is to the head of an organism.[40]

- Caudal(fromLatincauda'tail') describes how close something is to the trailing end of an organism.[41]

For example, inhorses,the eyes are caudal to the nose and rostral to the back of the head.

These terms are generally preferred in veterinary medicine and not used as often in human medicine.[42][43][44]In humans, "cranial" and "cephalic" are used to refer to the skull, with "cranial" being used more commonly. The term "rostral" is rarely used in human anatomy, apart from embryology, and refers more to the front of the face than the superior aspect of the organism. Similarly, the term "caudal" is used more in embryology and only occasionally used in human anatomy.[2]This is because the brain is situated at the superior part of the head whereas the nose is situated in the anterior part. Thus, the "rostrocaudal axis" refers to a C shape (see image).

Other terms and special cases

[edit]Anatomical landmarks

[edit]The location of anatomical structures can also be described in relation to differentanatomical landmarks.They are used in anatomy, surface anatomy, surgery, and radiology.[45]

Structures may be described as being at the level of a specificspinal vertebra,depending on the section of thevertebral columnthe structure is at.[45]The position is often abbreviated. For example, structures at the level of the fourthcervical vertebramay be abbreviated as "C4", at the level of the fourththoracic vertebra"T4", and at the level of the thirdlumbar vertebra"L3". Because thesacrumand coccyx are fused, they are not often used to provide the location.

References may also take origin fromsuperficial anatomy,made to landmarks that are on the skin or visible underneath.[45]For example, structures may be described relative to theanterior superior iliac spine,themedial malleolusor themedial epicondyle.

Anatomical linesare used to describe anatomical location. For example, the mid-clavicular line is used as part of thecardiac examin medicine to feel theapex beatof theheart.

Mouth and teeth

[edit]Special terms are used to describe the mouth and teeth.[2]Fields such asosteology,palaeontologyand dentistry apply special terms of location to describe the mouth and teeth. This is because although teeth may be aligned with their main axes within the jaw, some different relationships require special terminology as well; for example, teeth also can be rotated, and in such contexts terms like "anterior" or "lateral" become ambiguous.[46][47]For example, the terms "distal" and "proximal" are also redefined to mean the distance away or close to thedental arch,and "medial" and "lateral" are used to refer to the closeness to the midline of the dental arch.[48]Terms used to describe structures include "buccal" (fromLatinbucca'cheek') and "palatal" (fromLatinpalatum'palate') referring to structures close to thecheekandhard palaterespectively.[48]

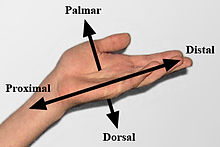

Hands and feet

[edit]

Several anatomical terms are particular to the hands and feet.[2]

Additional terms may be used to avoid confusion when describing the surfaces of the hand and what is the "anterior" or "posterior" surface. The term "anterior", while anatomically correct, can be confusing when describing thepalmof the hand; Similarly is "posterior", used to describe the back of the hand and arm. This confusion can arise because the forearm canpronateandsupinateand flip the location of the hand. For improved clarity, the directional termpalmar(fromLatinpalma'palm of the hand') is commonly used to describe the front of the hand, anddorsalis the back of the hand. For example, the top of adog'spawis its dorsal surface; the underside, either the palmar (on the forelimb) or the plantar (on the hindlimb) surface. Thepalmar fasciaispalmarto thetendonsof muscles which flex the fingers, and thedorsal venous archis so named because it is on the dorsal side of the foot.

In humans,volarcan also be used synonymously withpalmarto refer to the underside of thepalm,butplantaris used exclusively to describe thesole.These terms describe location aspalmarandplantar;For example,volarpads are those on the underside of hands or fingers; theplantarsurface describes the sole of the heel, foot or toes.

Similarly, in the forearm, for clarity, the sides are named after the bones. Structures closer to theradiusareradial,structures closer to theulnaareulnar,and structures relating to both bones are referred to asradioulnar.Similarly, in the lower leg, structures near thetibia(shinbone) aretibialand structures near thefibulaarefibular(orperoneal).

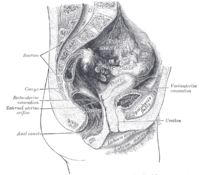

Rotational direction

[edit]Anteversionandretroversionare complementary terms describing an anatomical structure that is rotated forwards (towards the front of the body) or backwards (towards the back of the body), relative to some other position. They are particularly used to describe the curvature of theuterus.[49][50]

- Anteversion(fromLatinanteversus) describes an anatomical structure being tilted furtherforwardthan normal, whether pathologically or incidentally.[49]For example, a woman'suterustypically is anteverted, tilted slightlyforward.A misalignedpelvismay be anteverted, that is to say tiltedforwardto some relevant degree.

- Retroversion(fromLatinretroversus) describes an anatomical structure tiltedbackaway from something.[50]An example is aretroverted uterus.[50]

Other directional terms

[edit]Several other terms are also used to describe location. These terms are not used to form the fixed axes. Terms include:

- Axial(fromLatinaxis'axle'): around the central axis of the organism or the extremity. Two related terms, "abaxial" and "adaxial", refer to locations away from and toward the central axis of an organism, respectively

- Luminal(fromLatinlumen'light, opening'): on the—hollow—inside of an organ'slumen(body cavity or tubular structure);[51][52]adluminalis towards,abluminalis away from the lumen.[53]Opposite tooutermost(theadventitia,serosa,or the cavity's wall).[54]

- Parietal(fromLatinparies'wall'): pertaining to the wall of a body cavity.[55]For example, theparietal peritoneumis the lining on the inside of the abdominal cavity. Parietal can also refer specifically to theparietal boneof the skull or associated structures.

- Terminal(fromLatinterminus'boundary or end') at the extremity of a usually projecting structure.[56]For example, "...an antenna with a terminal sensory hair".

- Visceralandviscus(fromLatinviscera'internal organs'): associated with organs within the body's cavities.[57]For example, thestomachis covered with a lining called the visceralperitoneumas opposed to the parietal peritoneum. Viscus can also be used to mean "organ".[57]For example, the stomach is a viscus within the abdominal cavity, andvisceral painrefers to pain originating from internal organs.

- Aboral(opposite tooral) is used to denote a location along thegastrointestinal canalthat is relatively closer to theanus.[58]

Specific animals and other organisms

[edit]Different terms are used because of differentbody plansin animals, whether animals stand on one or two legs, and whether an animal is symmetrical or not, as discussed above. For example, as humans are approximatelybilaterally symmetricalorganisms, anatomical descriptions usually use the same terms as those for other vertebrates.[59]However, humans stand upright on two legs, meaning their anterior/posterior and ventral/dorsal directions are the same, and the inferior/superior directions are necessary.[60]Humans do not have abeak,so a term such as "rostral" used to refer to the beak in some animals is instead used to refer to part of the brain;[61]humans do also not have a tail so a term such as "caudal" that refers to the tail end may also be used in humans and animals without tails to refer to the hind part of the body.[62]

Ininvertebrates,the large variety of body shapes presents a difficult problem when attempting to apply standard directional terms. Depending on the organism, some terms are taken by analogy from vertebrate anatomy, and appropriate novel terms are applied as needed. Some such borrowed terms are widely applicable in most invertebrates; for example proximal, meaning "near" refers to the part of an appendage nearest to where it joins the body, and distal, meaning "standing away from" is used for the part furthest from the point of attachment. In all cases, the usage of terms is dependent on thebody planof the organism.

-

Anatomical terms of location in adog

-

Anatomical terms of location in akangaroo

-

Anatomical terms of location in afish

-

Anatomical terms of location in ahorse

Asymmetrical and spherical organisms

[edit]

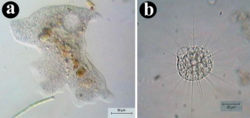

In organisms with a changeable shape, such asamoeboidorganisms, most directional terms are meaningless, since the shape of the organism is not constant and no distinct axes are fixed. Similarly, inspherically symmetricalorganisms, there is nothing to distinguish one line through the centre of the organism from any other. An indefinite number of triads of mutually perpendicular axes could be defined, but any such choice of axes would be useless, as nothing would distinguish a chosen triad from any others. In such organisms, only terms such assuperficialanddeep,or sometimesproximalanddistal,are usefully descriptive.

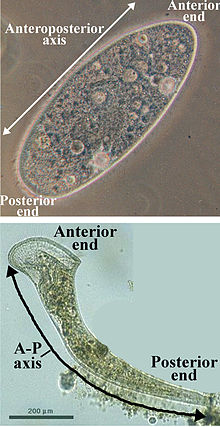

Elongated organisms

[edit]In organisms that maintain a constant shape and have one dimension longer than the other, at least two directional terms can be used. Thelongorlongitudinal axisis defined by points at the opposite ends of the organism. Similarly, a perpendiculartransverse axiscan be defined by points on opposite sides of the organism. There is typically no basis for the definition of a third axis. Usually such organisms areplanktonic(free-swimming)protists,and are nearly always viewed onmicroscope slides,where they appear essentially two-dimensional. In some cases a third axis can be defined, particularly where a non-terminalcytostomeor other unique structure is present.[44]

Some elongatedprotistshave distinctive ends of the body. In such organisms, the end with a mouth (or equivalent structure, such as thecytostomeinParameciumorStentor), or the end that usually points in the direction of the organism'slocomotion(such as the end with theflagelluminEuglena), is normally designated as theanteriorend. The opposite end then becomes theposterior end.[44]Properly, this terminology would apply only to an organism that is alwaysplanktonic(not normally attached to a surface), although the term can also be applied to one that issessile(normally attached to a surface).[63]

Organisms that are attached to asubstrate,such assponges,animal-like protistsalso have distinctive ends. The part of the organism attached to the substrate is usually referred to as thebasal end(fromLatinbasis'support/foundation'), whereas the end furthest from the attachment is referred to as theapical end(fromLatinapex'peak/tip').

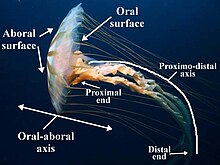

Radially symmetrical organisms

[edit]Radially symmetrical organismsinclude those in the groupRadiata– primarilyjellyfish, sea anemones and coralsand thecomb jellies.[42][44]Adultechinoderms,such asstarfish,sea urchins,sea cucumbersand others are also included, since they are pentaradial, meaning they have fivediscrete rotationalsymmetry.Echinodermlarvaeare not included, since they arebilaterally symmetrical.[42][44]Radially symmetrical organisms always have one distinctive axis.

Cnidarians(jellyfish, sea anemones and corals) have an incomplete digestive system, meaning that one end of the organism has a mouth, and the opposite end has no opening from the gut (coelenteron).[44]For this reason, the end of the organism with the mouth is referred to as theoral end(fromLatinōrālis'of the mouth'),[64]and the opposite surface is theaboral end(fromLatinab-'away from').[65]

Unlike vertebrates, cnidarians have only a single distinctive axis. "Lateral", "dorsal", and "ventral" have no meaning in such organisms, and all can be replaced by the generic termperipheral(fromAncient Greekπεριφέρεια'circumference').Medialcan be used, but in the case of radiates indicates the central point, rather than a central axis as in vertebrates. Thus, there are multiple possibleradial axesandmedio-peripheral(half-)axes.However, some biradially symmetricalcomb jelliesdo have distinct "tentacular" and "pharyngeal" axes[66][67]and are thus anatomically equivalent tobilaterally symmetricalanimals.

-

Aurelia aurita,another species ofjellyfish,showing multiple radial and medio-peripheral axes

-

Thesea starPorania pulvillus,aboral and oral surfaces

Spiders

[edit]Special terms are used forspiders.Two specialized terms are useful in describing views ofarachnidlegs andpedipalps.Prolateralrefers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the anterior end of an arachnid's body.Retrolateralrefers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the posterior end of an arachnid's body.[68]Most spiders have eight eyes in four pairs. All the eyes are on thecarapaceof theprosoma,and their sizes, shapes and locations are characteristic of various spider families and othertaxa.[69]Usually, the eyes are arranged in two roughly parallel, horizontal and symmetrical rows of eyes.[69]Eyes are labelled according to their position as anterior and posterior lateral eyes (ALE) and (PLE); and anterior and posterior median eyes (AME) and (PME).[69]

-

Aspects of spider anatomy. This aspect shows the mainly prolateral surface of the anterior femora, plus the typical horizontal eye pattern of theSparassidae.

-

Typical arrangement of eyes in theLycosidae,with PME being the largest

-

In theSalticidaethe AME are the largest.

See also

[edit]- Chirality

- Geometric terms of location

- Handedness

- Laterality

- Proper right and proper left

- Reflection symmetry

- Sinistral and dextral

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abcdefghiDyce, Sack & Wensing 2010,pp. 2–3.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoGray's Anatomy 2016,pp. xvi–xvii.

- ^abcdKardong's 2019,p. 16.

- ^Hofer, Matthias (2006).The Chest X-ray: A Systematic Teaching Atlas.Thieme. p. 24.ISBN978-3-13-144211-6.

- ^"dorsolateral".Merriam-Webster.29 September 2023.

- ^abWake 1992,p. 6.

- ^Collins 2020,"axis", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Anteroposterior", accessed 14 October 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Cephalocaudal", accessed 14 October 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Dorsoventral", accessed 14 October 2020.

- ^Pellerito, John; Polak, Joseph F. (2012).Introduction to Vascular Ultrasonography(6th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p.559.ISBN978-1-4557-3766-6.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Sub-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Hypo-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Infra-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Inter-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"Super-" and "Supra-", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"-ad", accessed on 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"an-", accessed on 17 July 2020.

- ^Gordh, Gordon; Headrick, David H (2011).A Dictionary of Entomology(2nd ed.). CABI.ISBN978-1845935429.

- ^Collins 2020,"superior", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"inferior", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"anterior", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"posterior", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"contralateral", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"ipsilateral", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"bilateral", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"unilateral", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"varus" and "valgus", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^Wake 1992,p. 5.

- ^"What do distal and proximal mean?".The Survival Doctor.2011-10-05.Retrieved2016-01-07.

- ^Hutchinson, J.M.C. (2022)."Lippen are not lips, and other nomenclatural confusions".Mitteilungen der Deutschen Malakozoologischen Gesellschaft.107:3–7.

- ^Singh, S (8 March 2000). "Chemistry, design, and structure-activity relationship of cocaine antagonists".Chemical Reviews.100(3): 925–1024.doi:10.1021/cr9700538.PMID11749256.

- ^abCollins 2020,"central", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"peripheral", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"deep", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"profound", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^Collins 2020,"superficial", accessed 2 July 2020.

- ^abGO 2014,"dorsal/ventral axis specification" (GO:0009950).

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"rostral", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"cranial" and "cephalic", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"caudal", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^abcHickman, C. P. Jr., Roberts, L. S. and Larson, A.Animal Diversity.McGraw-Hill 2003ISBN0-07-234903-4

- ^Miller, S. A.General Zoology Laboratory ManualMcGraw-Hill,ISBN0-07-252837-0andISBN0-07-243559-3

- ^abcdefRuppert, EE; Fox, RS; Barnes, RD (2004).Invertebrate zoology: a functional evolutionary approach(7th ed.). Thomson, Belmont: Thomson-Brooks/Cole.ISBN0-03-025982-7.

- ^abcButler, Paul; Mitchell, Adam W. M.; Ellis, Harold (1999-10-14).Applied Radiological Anatomy.Cambridge University Press. p. 1.ISBN978-0-521-48110-6.

- ^Pieter A. Folkens (2000).Human Osteology.Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 558–.ISBN978-0-12-746612-5.

- ^Smith, J. B.; Dodson, P. (2003)."A proposal for a standard terminology of anatomical notation and orientation in fossil vertebrate dentitions".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.23(1): 1–12.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[1:APFAST]2.0.CO;2.S2CID8134718.

- ^abRajkumar, K.; Ramya, R. (2017).Textbook of Oral Anatomy, Physiology, Histology and Tooth Morphology.Wolters kluwer india Pvt Ltd. pp. 6–7.ISBN978-93-86691-16-3.

- ^abCollins 2020,"anteversion", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^abcCollins 2020,"retroversion", accessed 17 July 2020.

- ^William C. Shiel."Medical Definition of Lumen".MedicieNet.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^"NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms" lumen "".National Cancer Institute.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^""abluminal"".Merriam-WebsterMedical Dictionary.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^David King (2009)."Study Guide - Histology of the Gastrointestinal System".Southern Illinois University.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"parietal", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"terminal", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^abMerriam-Webster 2020,"visceral", accessed 3 July 2020.

- ^Morrice, Michael; Polton, Gerry; Beck, Sam (2019)."Evaluation of the extent of neoplastic infiltration in small intestinal tumours in dogs".Veterinary Medicine and Science.5(2): 189–198.doi:10.1002/vms3.147.ISSN2053-1095.PMC6498519.PMID30779310.

- ^Wake 1992,p. 1.

- ^Tucker, T. G. (1931).A Concise Etymological Dictionary of Latin.Halle (Saale): Max Niemeyer Verlag.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"rostral", accessed 14 October 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"caudal", accessed 14 October 2020.

- ^Valentine, James W. (2004).On the Origin of Phyla.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-84548-7.

- ^Collins 2020,"oral", accessed 13 October 2020.

- ^Merriam-Webster 2020,"aboral", accessed 13 October 2020.

- ^Oliveira, Otto Müller Patrão de."Chave de identificação dos Ctenophora da costa brasileira".Biota Neotropica.Retrieved6 April2023.

- ^Ruppert et al. (2004), p. 184.

- ^Kaston, B.J.(1972).How to Know the Spiders(3rd ed.). Dubuque, IA: W.C. Brown Co. p. 19.ISBN978-0-697-04899-8.OCLC668250654.

- ^abcFoelix, Rainer (2011).Biology of Spiders.Oxford University Press, US. pp. 17–19.ISBN978-0-19-973482-5.

General sources

[edit]- "Collins Online Dictionary | Definitions, Thesaurus and Translations".collinsdictionary.

- Dyce, KM; Sack, WO; Wensing, CJG (2010).Textbook of veterinary anatomy(4th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders/Elsevier.ISBN9781416066071.

- "GeneOntology".GeneOntology.The Gene Ontology Consortium.Retrieved26 October2014.

- Standring, Susan, ed. (2016).Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice(41st ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited.ISBN9780702052309.OCLC920806541.

- Kardong, Kenneth (2019).Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution(8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.ISBN9781260092042.

- "Dictionary by Merriam-Webster: America's most-trusted online dictionary".merriam-webster.

- Wake, Marvale H., ed. (1992).Hyman's comparative vertebrate anatomy(3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.ISBN9780226870113.

![Spheroid or near-spheroid organs such as testes may be measured by long and short axes.[11]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Long_and_short_axis.png/100px-Long_and_short_axis.png)