Bhikkhu

| Bhikkhu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bhikkhus in Thailand | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | Sư | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Native Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | Hòa thượng, tăng lữ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Burmese name | |||||||||

| Burmese | ဘိက္ခု | ||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | དགེ་སློང་ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese Alpha bet | Tì-kheo (Tỉ-khâu) Tăng lữ | ||||||||

| Chữ Hán | Sư Tăng lữ | ||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||

| Thai | ภิกษุ | ||||||||

| RTGS | phiksu | ||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | Tăng, sư | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tamil name | |||||||||

| Tamil | துறவி, tuṟavi | ||||||||

| Sanskrit name | |||||||||

| Sanskrit | भिक्षु (Bhikṣu) | ||||||||

| Pali name | |||||||||

| Pali | Bhikkhu | ||||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||||

| Khmer | ភិក្ខុ UNGEGN:Phĭkkhŏ ALA-LC:Bhikkhu | ||||||||

| Nepali name | |||||||||

| Nepali | भिक्षु | ||||||||

| Sinhala name | |||||||||

| Sinhala | භික්ෂුව | ||||||||

| Telugu name | |||||||||

| Telugu | భిక్షువు, bhikṣuvu | ||||||||

| Odia name | |||||||||

| Odia | ଭିକ୍ଷୁ, Bhikhyu | ||||||||

Abhikkhu(Pali:भिक्खु,Sanskrit:भिक्षु,bhikṣu) is an ordained male inBuddhist monasticism.[1]Male and female monastics ( "nun",bhikkhunī,Sanskritbhikṣuṇī) are members of theSangha(Buddhist community).[2]

The lives of all Buddhist monastics are governed by a set of rules called theprātimokṣaorpātimokkha.[1]Their lifestyles are shaped to support their spiritual practice: to live a simple and meditative life and attainnirvana.[3]

A person under the age of 20 cannot be ordained as a bhikkhu or bhikkhuni but can be ordained as aśrāmaṇera or śrāmaṇērī.

Definition

[edit]Bhikkhuliterally means "beggar"or" one who lives byalms".[4]The historical Buddha,Prince Siddhartha,having abandoned a life of pleasure and status, lived as an almsmendicantas part of hisśramaṇalifestyle. Those of his more serious students who renounced their lives as householders and came to study full-time under his supervision also adopted this lifestyle. These full-time student members of thesanghabecame the community of ordained monastics who wandered from town to city throughout the year, living off alms and stopping in one place only for theVassa,the rainy months of the monsoon season.

In theDhammapadacommentary ofBuddhaghoṣa,a bhikkhu is defined as "the person who sees danger (in samsara or cycle of rebirth)" (Pāli:Bhayaṃikkhatīti: bhikkhu). Therefore, he seeksordinationto obtain release from the cycle of rebirth.[5]TheDhammapadastates:[6]

[266–267] He is not a monk just because he lives on others' alms. Not by adopting outward form does one become a true monk. Whoever here (in the Dispensation) lives a holy life, transcending both merit and demerit, and walks with understanding in this world — he is truly called a monk.

Buddha accepted female bhikkhunis after his step-motherMahapajapati Gotamiorganized a women's march to Vesāli. and Buddha requested her to accept theEight Garudhammas.So, Gotami agreed to accept the Eight Garudhammas and was accorded the status of the first bhikkhuni. Subsequent women had to undergo full ordination to become nuns.[7]

Ordination

[edit]Theravada

[edit]Theravada monasticism is organized around the guidelines found within a division of thePāli Canoncalled theVinaya Pitaka.Laypeople undergo ordination as a novitiate (śrāmaṇera or sāmanera) in a rite known as the "going forth" (Pali:pabbajja). Sāmaneras are subject to theTen Precepts.From there full ordination (Pali:upasampada) may take place. Bhikkhus are subject to a much longer set of rules known as thePātimokkha(Theravada) orPrātimokṣa(Mahayana andVajrayana).

Mahayana

[edit]

In the Mahayana monasticism is part of the system of "vows of individual liberation".[5]These vows are taken by monks and nuns from the ordinary sangha, in order to develop personal ethical discipline.[5]InMahayanaand Vajrayana, the term "sangha" is, in principle, often understood to refer particularly to thearyasangha(Wylie:mchog kyi tshogs), the "community of the noble ones who have reached the firstbhūmi".These, however, need not be monks and nuns.

The vows of individual liberation are taken in four steps. A lay person may take the fiveupāsaka and upāsikāvows (Wylie:dge snyan (ma),"approaching virtue" ). The next step is to enter thepabbajjaor monastic way of life (Skt:pravrajyā,Wylie:rab byung), which includes wearing monk's or nun's robes. After that, one can become a samanera or samaneri "novice" (Skt.śrāmaṇera,śrāmaṇeri,Wylie:dge tshul, dge tshul ma). The final step is to take all the vows of a bhikkhu orbhikkhuni"fully ordained monastic" (Sanskrit:bhikṣu, bhikṣuṇī,Wylie:dge long (ma)).

Monastics take their vows for life but can renounce them and return to non-monastic life[8]and even take the vows again later.[8]A person can take them up to three times or seven times in one life, depending on the particular practices of each school of discipline; after that, the sangha should not accept them again.[9]In this way, Buddhism keeps the vows "clean". It is possible to keep them or to leave this lifestyle, but it is considered extremely negative to break these vows.

In 9th century Japan, the monkSaichōbelieved the 250 precepts were for theŚrāvakayānaand that ordination should use theMahayana preceptsof theBrahmajala Sutra.He stipulated that monastics remain onMount Hieifor twelve years of isolated training and follow the major themes of the 250 precepts: celibacy, non-harming, no intoxicants, vegetarian eating and reducing labor for gain. After twelve years, monastics would then use the Vinaya precepts as a provisional or supplemental, guideline to conduct themselves by when serving in non-monastic communities.[10]Tendaimonastics followed this practice.

During Japan'sMeiji Restorationduring the 1870s, the government abolished celibacy and vegetarianism for Buddhist monastics in an effort to secularise them and promote the newly createdState Shinto.[11][12]Japanese Buddhistswon the right to proselytize inside cities, ending a five-hundred year ban on clergy members entering cities.[13][page needed]Currently, priests (lay religious leaders) in Japan choose to observe vows as appropriate to their family situation. Celibacy and other forms of abstaining are generally "at will" for varying periods of time.

After theJapan–Korea Treaty of 1910,when Japan annexed Korea, Korean Buddhism underwent many changes.Jōdo ShinshūandNichiren schoolsbegan sending missionaries toKorea under Japanese ruleand new sects formed there such asWon Buddhism.The Temple Ordinance of 1911 (Korean:사찰령;Hanja:Chùa sát lệnh) changed the traditional system whereby temples were run as a collective enterprise by the Sangha, replacing this system with Japanese-style management practices in which temple abbots appointed by theGovernor-General of Koreawere given private ownership of temple property and given the rights of inheritance to such property.[14]More importantly, monks from pro-Japanese factions began to adopt Japanese practices, by marrying and having children.[14]

In Korea, the practice of celibacy varies. The two sects ofKorean Seondivided in 1970 over this issue; theJogye Orderis fully celibate while theTaego Orderhas both celibate monastics and non-celibate Japanese-style priests.

Vajrayana

[edit]InTibet,the upāsaka, pravrajyā and bhikṣu ordinations are usually taken at ages six, fourteen and twenty-one or older, respectively.

TibetanVajrayanaoften calls ordained monkslama.[15]

Additional vows in the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions

[edit]In Mahayana traditions, a Bhikṣu may take additional vows not related to ordination, including theBodhisattva vows,samayavows and others, which are also open to laypersons in most instances.

Robes

[edit]

The special dress of ordained people, referred to in English asrobes,comes from the idea of wearing a simple durable form of protection for the body from weather and climate. In each tradition, there is uniformity in the color and style of dress. Color is often chosen due to the wider availability of certain pigments in a given geographical region. In Tibet and the Himalayan regions (Kashmir, Nepal and Bhutan), red is the preferred pigment used in the dyeing of robes. In Myanmar, reddish brown; In India, Sri Lanka and South-East Asia, various shades of yellow, ochre and orange prevail. In China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, gray or black is common. Monks often make their own robes from cloth that is donated to them.[1]

The robes of Tibetan novices and monks differ in various aspects, especially in the application of "holes" in the dress of monks. Some monks tear their robes into pieces and then mend these pieces together again.Upāsakascannot wear the "chö-göö", a yellow tissue worn during teachings by both novices and full monks.

In observance of theKathina Puja,a special Kathina robe is made in 24 hours from donations by lay supporters of a temple. The robe is donated to the temple or monastery and the resident monks then select from their own number a single monk to receive this special robe.[16]

Gallery

[edit]-

A Theravadin Buddhist monk in Laos

-

A Theravadin Buddhist monk in USA

-

A Chinese Buddhist monk in mainland China

-

A Chinese Buddhist monk in Taiwan

-

A Buddhist monk in the U.S. (Chinese Buddhism)

-

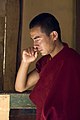

A Buddhist monk in Tibet

-

Monks inLuang Prabang,Laos

-

Monks inThailand

-

Monks inMyanmar (Burma)

Historical terms in Western literature

[edit]

InEnglishliterature before the mid-20th century, Buddhist monks, particularly from East Asia and French Indochina, were often referred to by the termbonze.This term is derived fromPortugueseandFrenchfromJapanesebonsō'priest, monk'. It is rare in modern literature.[17]

Buddhist monks were once calledtalapoyortalapoinfromFrenchtalapoin,itself fromPortuguesetalapão,ultimately fromMontala pōi'our lord'.[18][19]

The Talapoys cannot be engaged in any of the temporal concerns of life; they must not trade or do any kind of manual labour, for the sake of a reward; they are not allowed toinsultthe earth by digging it. Having no tie, which unites their interests with those of the people, they are ready, at all times, with spiritual arms, to enforce obedience to the will of the sovereign.

— Edmund Roberts,Embassy to the eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat[19]

Thetalapoinis a monkey named after Buddhist monks just as thecapuchin monkeyis named after theOrder of Friars Minor Capuchin(who also are the origin of the wordcappuccino).

See also

[edit]| People of thePāli Canon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^abc"Lay Guide to the Monks' Rules".Archivedfrom the original on 2016-12-02.Retrieved2010-11-08.

- ^Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2004).Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Monasticism).Macmillan Reference USA. p. 556.ISBN0-02-865718-7.

- ^"What is a bhikkhu?".Archivedfrom the original on 2010-11-28.Retrieved2010-11-25.

- ^Buddhist Dictionary, Manual of Buddhist Terms and DoctrinesbyNyanatilokaMahathera.

- ^abc"Resources: Monastic Vows".Archived fromthe originalon 2014-10-14.Retrieved2010-11-08.

- ^Buddharakkhita, Acharya."Dhammapada XIX — Dhammatthavagga: The Just".Access To Insight.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2012.Retrieved18 December2012.

- ^"Life of Buddha: Maha Pajapati Gotami - Order of Nuns (Part 2)".buddhanet.net.Archivedfrom the original on 2010-12-13.Retrieved2021-01-24.

- ^ab"how to become a monk?".Archivedfrom the original on 2010-11-26.Retrieved2010-11-25.

- ^"05-05《 luật chế sinh hoạt 》p. 0064".Archived fromthe originalon 2017-04-24.Retrieved2010-03-13.

- ^Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Soka Gakkai, 'Dengyo'

- ^"Shinto history".Archivedfrom the original on 2011-12-11.Retrieved2011-12-05.

- ^"JAPANESE BUDDHISM TODAY".Archivedfrom the original on 2011-12-10.Retrieved2011-12-05.

- ^Clark, Donald N. (2000).Culture and customs of Korea.Greenwood Publishing Group.ISBN978-0-313-30456-9.

- ^abSorensen, Henrik Hjort (1992). Ole Bruun; Arne Kalland; Henrik Hjort Sorensen (eds.).Asian perceptions of nature.Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.ISBN978-87-87062-12-1.

- ^Cohen, David, ed. (1989).A Day in the Life of China.San Francisco:Collins.p. 129.ISBN978-0-00-215321-8.

- ^Buddhist Ceremonies and Rituals of Sri LankaArchived2013-03-28 at theWayback Machine,A.G.S. Kariyawasam

- ^"Dictionary: bonze".Archivedfrom the original on 2003-02-28.Retrieved2008-06-10.

- ^"talapoin".Collins Concise English Dictionary © HarperCollins Publishers.WordReference. June 23, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on May 25, 2013.RetrievedJune 23,2013.

Etymology: 16th Century: from French, literally: Buddhist monk, from Portuguese talapão, from Mon tala pōi our lord...

- ^abRoberts 1837,p. 237.

Sources

[edit]- Roberts, Edmund(1837).Embassy to the eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat: in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock... during the years 1832–3–4.Harper & brothers.ISBN9780608404066.

Further reading

[edit]- Inwood, Kristiaan.Bhikkhu, Disciple of the Buddha.Bangkok, Thailand: Thai Watana Panich, 1981. Revised edition. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2005.ISBN978-974-524-059-9.

External links

[edit]Buddhist monks.