Bookmobile

Abookmobile,ormobile library,is a vehicle designed for use as a library.[1][2]They have been known by many names throughout history, including traveling library, library wagon, book wagon, book truck, library-on-wheels, and book auto service.[3]Bookmobiles expand the reach of traditional libraries by transporting books to potential readers, providing library services to people in otherwise underserved locations (such as remote areas) and/or circumstances (such as residents ofretirement homes). Bookmobile services and materials (such as Internet access,large printbooks, andaudiobooks), may be customized for the locations and populations served.[4]

Bookmobiles have been based on various means of conveyance, including bicycles, carts, motor vehicles, trains, watercraft, and wagons, as well as camels, donkeys, elephants, horses, and mules.[3][4]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]

In the United States of America,The American School Library(1839) was a traveling frontier library published byHarper & Brothers.The Smithsonian Institution'sNational Museum of American Historyhas the only complete original set of this series complete with its wooden carrying case.[5]

The British Workmanreported in 1857[6]about a perambulating library operating in a circle of eight villages, inCumbria.[7]A Victorian merchant and philanthropist, George Moore, had created the project to "diffuse good literature among the rural population".[8]

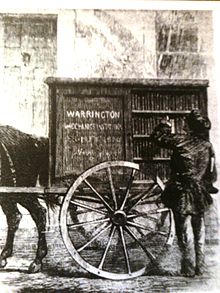

TheWarrington Perambulating Library,set up in 1858, was another early British mobile library.[2]This horse-drawn van was operated by the WarringtonMechanics' Institute,which aimed to increase the lending of its books to enthusiastic local patrons.[9]

During the late 1800s, Women's Clubs began advocating for Bookmobiles in the state of Texas and throughout the United States. Kate Rotan of the Women's Club in Waco, Texas was the first to advocate for bookmobiles. She was president of the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs (TFWC). During this time Women's Clubs were encouraged to promote bookmobiles because they embraced their ideas and missions. After receiving so much support and promotion these traveling libraries increased in numbers all around the United States. In the state of New York from 1895 to 1898 the number of bookmobiles increased to 980. The United States Women Clubs became their primary advocate.[10]

20th century

[edit]

The Women's Club movement in 1904, had the standard to be held accountable for the influx of bookmobiles in thirty out of fifty states. Because of the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs (TFWC), a new legislation to develop public libraries in Texas became possible after much advocating from TFWC for bookmobiles. This new legislation brought in library improvements and expansions that included establishing a system of traveling libraries in Texas. Women's Clubs wanted state governments to step in and create commissions for these traveling libraries. They hoped the commissions would boost the managers of the bookmobile's "Library Sprit". Unfortunately, the Texas Library Association (TLA) could not provide the type of service that is already provided to state libraries to bookmobiles.[10]

One of the earliest mobile libraries in the United States was a mule-drawn wagon carrying wooden boxes of books. It was created in 1904 by the People's Free Library ofChester County, South Carolina,and served the rural areas there.[11]

Another early mobile library service was developed byMary Lemist Titcomb(1857–1932).[12][13][14][15]As a librarian inWashington County, Maryland,Titcomb was concerned that the library was not reaching all the people it could.[13]Meant as a way to reach more library patrons, the annual report for 1902 listed 23 deposit stations, with each being a collection of 50 books in a case that was placed in a store or post office throughout the county.[16]Although popular, Titcomb realized that even this did not reach the most rural residents, and so she cemented the idea of a "book wagon" in 1905, taking the library materials directly to people's homes in remote parts of the county.[4][17][7][15][18]After securing a Carnegie gift of $2,500, Titcomb purchased a black Concord wagon and employed the library janitor to drive it.[19]The book wagon proved popular, with 1,008 volumes distributed within its first six months.[20]

With the rise of motorized transport in America, a pioneering librarian in 1920 namedSarah Byrd Askewbegan driving her specially outfittedModel Tto provide library books to rural areas in New Jersey.[21]The automobile remained rare, however, and in Minneapolis, theHennepin County Public Libraryoperated a horse-drawn book wagon starting in 1922.[22]

Following theGreat Depression in the United States,aWPAeffort from 1935 to 1943 called thePack Horse Library Projectcovered the remote coves and mountainsides of Kentucky and nearby Appalachia, bringing books and similar supplies on foot and on hoof to those who could not make the trip to a library on their own. Sometimes these "packhorse librarians" relied on a centralized contact to help them distribute the materials.[23]

AtFairfax County, Virginia,county-wide bookmobile service was begun in 1940, in a truck loaned by theWorks Progress Administration( "WPA" ). The WPA support of the bookmobile ended in 1942, but the service continued.[24]

The "Library in Action" was a late-1960s bookmobile program in theBronx, NY,run by interracial staff that brought books to teenagers of color in under-served neighborhoods.[25]

Bookmobiles reached the height of their popularity in the mid-twentieth century.[4][15][26]

In England, bookmobiles, or "traveling libraries" as they were called in that country, were typically used in rural and outlying areas. However, during World War II, one traveling library found popularity in the city of London. Because of air raids and blackouts, patrons did not visit the Metropolitan Borough of Saint Pancras's physical libraries as much as before the war. To meet the needs of its citizens, the borough borrowed a traveling library van from Hastings and in 1941 created a "war-time library on wheels." (The Saint Pancras borough was abolished in 1965 and became part of the London Borough of Camden.)

The Saint Pancras traveling library consisted of a van mounted on a six-wheel chassis powered by a Ford engine. The traveling library could carry more than 2,000 books on open-access shelves that ran the length of the van. The books were arranged in Dewey order, and up to 20 patrons could fit into the van at one time to browse and check out materials. A staff enclosure was at the rear of the van, and the van was lighted with windows in the roof – each fitted with black-out curtains in case of a German bombing raid. The van could even be used at night, as it was fitted with electric roof lamps that could access electrical current from a nearby lamp-standard or civil defense post. The traveling library had a selection of fiction and non-fiction works; it even had a children's section with fairy tales and non-fiction books for kids.

The mayor of the borough christened the van with a speech, saying that "People without books are like houses without windows." Even after heavy night bombings by the Germans, readers visited the Saint Pancras Traveling Library in some of the worst bombed areas.[27]

21st century

[edit]Bookmobiles are still in use in the 21st century, operated by libraries, schools, activists, and other organizations. Although some[who?]feel that the bookmobile is an outmoded service, citing reasons like high costs, advanced technology, impracticality, and ineffectiveness, others cite the ability of the bookmobile to be more cost-efficient than building more branch libraries would be and its high use among its patrons as support for its continuation.[28]To meet the growing demand for "greener" bookmobiles that deliver outreach services to their patrons, some bookmobile manufacturers have introduced significant advances to reduce theircarbon footprint,such as solar/battery solutions in lieu of traditional generators, and all-electric and hybrid-electric chassis.[citation needed]Bookmobiles have also taken on an updated form in the form ofm libraries,[29]also known asmobile libraries[30]in which patrons are delivered content electronically.[31]

TheInternet Archiveruns its own bookmobile to print out-of-copyright books on demand.[32]The project has spun off similar efforts elsewhere in the developing world.[33]

The Free Black Women's Libraryis a mobile library in Brooklyn. Founded by Ola Ronke Akinmowo in 2015, this bookmobile features books written by black women. Titles are available in exchange for other titles written by black female authors.[34]

National Bookmobile Day

[edit]In the U.S., theAmerican Library Associationsponsors National Bookmobile Day in April each year, on the Wednesday ofNational Library Week.[35][36]They celebrate the nation's bookmobiles and the dedicated library professionals who provide this service to their communities.[4]

In February 2021, the American Library Association (ALA), the Association of Bookmobile and Outreach Services (ABOS), and the Association for Rural and Small Libraries (ARSL) agreed to rebrand National Bookmobile Day in recognition of all that outreach library professional do within their communities. Instead, libraries across the country will observe National Library Outreach Day on April 7, 2021. Formerly known as National Bookmobile Day, communities will celebrate the invaluable role library professionals and libraries continuous play in bringing library services to those in need.[37][4]

Countries

[edit]Africa

[edit]- In Kenya, the Camel Mobile Library Service is funded by theNational Library Service of Kenyaand byBook Aid Internationaland it operates inGarissaandWajir,near the border withSomalia.The service started with three camels in October 1996 and had 12 in 2006, delivering more than 7,000 books[38]—in English,Somali,andSwahili.[13][39]Masha Hamiltonused this service as a background for her 2007 novelThe Camel Bookmobile.[40]

- "Donkey Drawn Electro-Communication Library Carts" were being employed inZimbabwein 2002 as "a centre for electric and electronic communication: radio, telephone, fax, e-mail, Internet".[41]

Asia

[edit]

- InBangladeshBishwo Shahitto Kendropioneered the concept of mobile library. Mobile library was introduced in Bangladesh in 1999. Then the service was limited toDhaka,Chattogram,KhulnaandRajshahionly. Now the service is available in 58 districts of the country. There are about 330,000 registered users of this library. These mobile libraries together gives the service of 1900 small libraries in 1900 localities of the country.

- InBrunei,mobile libraries are known asPerpustakaan Bergerak.They are operated byDewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Brunei,the government body which manages public libraries in the country. The service was introduced in 1970.[42]

- In Indonesia in 2015, Ridwan Sururi and his horse "Luna" started a mobile library calledKudapustaka(meaning "horse library" in Indonesian). The goal is to improve access to books for villagers in a region that has more than 977,000 illiterate adults. The duo travel between villages incentral Javawith books balanced on Luna's back. Sururi also visits schools three times a week.[43]

- InThailandin 2002, mobile libraries were taking several unique forms.[44]

- Elephant Libraries were bringing books as well as information technology equipment and services to 46 remote villages in the hills ofNorthern Thailand.[13]This project was awarded theUNESCOInternational Literacy Prize for 2002.

- A Floating Library had two book boats, one of which was outfitted with computers.

- A three-car "Library Train for Homeless Children" (parked in a siding near the railway police compound) was a "joint project with the railway police in an initiative to keep homeless children from crime and exploitation by channeling them to more constructive activities". The train was being replicated in "a slum community inBangkok",where it, too, would include a library car, a classroom car, and a computer and music car.

- Book Houses were shipping containers fitted out as libraries with books. The 10 original Book Houses were so popular, another 20 units were already being planned.

- InIndia,theBoat Library Serviceswere operated under the auspices of theAndhra Pradesh Library Association,Vijayawada,Andhra Pradesh State.Paturi Nagabhushanaminitiated boat libraries to inculcate interest in reading of books and libraries among the rural public in 1935 October, as an extended activity of Andhra Pradesh Library Movement. He had run this service for about seven years to benefit the villagers travelling on boats, which was a major travel and transportation facility available in those days. These libraries facilitatedTeluguliterary journals and books.,[45][46]

Australia

[edit]- The First bookmobile in the State ofVictoriawas operated by Heidelberg Library (nowYarra Plenty Regional Library) in theCity of Heidelberg,Melbournein 1954.[47]

Europe

[edit]

- InGlasgow,Scotland, in 2002, MobileMeet—a gathering of about 50 mobile libraries that was held annually by theIFLA—there were "mobiles from Sweden, Holland, Ireland, England, and of course Scotland. There were big vans from Edinburgh and small vans from the Highlands. Many of the vans were proudly carrying awards from previous meets."[44]

- Since 1953, the Libraries of the Community ofMadrid,Spain, have operated abibliobusprogram with books, DVDs, CDs, and other library materials available for checkout.[49][50]

- A floating library, aboard the shipEpos,was begun in 1959 and serves the many small communities on the coast ofWestern Norway.

- InEstonia,the bookmobile "Katarina Jee" has been running since 2008, serving patrons in suburbs of Tallinn.

- In Finland, the first mobile library was established inVantaain 1913.[51]There are currently about 200 bookmobiles in Finland, operating across the country.

North America

[edit]- Street Booksis a nonprofit book service founded in 2011 inPortland, Oregon,that travels via bicycle-powered cart to lend books to "people living outside".[52]

- Books on Bikes[53]is a program begun in 2013 by theSeattle Public Librarythat uses a customized bicycle trailer pulled by pedal power to bring library services to community events in Seattle.[54]

- The Library Cruiser is a "book bike" from theVolusia CountyLibraries that debuted in Florida in September 2015. Library staff ride it to various locations, offering library books for checkout, as well as WiFi service, ebook access help, and information on obtaining a library card.[55]

South America

[edit]- TheBiblioburrois a mobile library by which Colombian teacher Luis Soriano and his two donkeys, Alfa and Beto, bring books to children in rural villages twice a week.CNNchose Soriano as one of their 2010 Heroes of the Year.[4][56][13]

Gallery

[edit]- Mobile libraries around the world

-

Bangladesh - 2020

-

Brazil - 2011

-

Brazil - 2017

-

Colombia - 2006

Biblioburro -

Norway - 2011

Epos -

Switzerland - 2007

-

Fresno County, California (United States) - 2019

-

Prague,Czech Republic- 2023

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"bookmobile".Merriam-Webster.Archived fromthe originalon 23 April 2009.Retrieved22 October2022.

- ^abEveleth, Rose(11 October 2013)."The Earliest Libraries-On-Wheels Looked Way Cooler Than Today's Bookmobiles".Smithsonian Magazine.Archived fromthe originalon 18 May 2014.Retrieved21 October2022.

- ^abBashaw, Diane (2010)."On the Road Again: A Look at Bookmobiles, Then and Now".Children & Libraries: The Journal of the Association for Library Service to Children.3(1): 33.Retrieved23 April2022.

- ^abcdefghPan, Connie (12 April 2022)."The History of Bookmobiles: Bookmobiles are here, and there and everywhere, to stay".Archived fromthe originalon 12 April 2022.Retrieved21 October2022.

- ^Olmert, Michael (1992)."The Infinite Library, Timeless and Incorruptible".The Smithsonian book of books(1. ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.ISBN0-89599-030-X.

- ^"Perambulating Library".The British Workman.1 February 1857.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2012.Retrieved27 May2011.

- ^ab"Bookmobiles: A Proud History, a Promising Future".American Libraries.11 April 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 15 March 2017.Retrieved21 October2022.

- ^"George Moore".Mealsgate.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2012.Retrieved1 September2011.

- ^Orton, Ian (1980).An Illustrated History of Mobile Library Services in the UK with notes on traveling libraries and early public library transport.Sudbury: Branch and Mobile Libraries Group of the Library Association.ISBN0-85365-640-1.

- ^abCummings, Jennifer. "'How Can We Fail?' The Texas State Library's Traveling Libraries and Bookmobiles, 1916-1966." Libraries & the Cultural Record, vol. 44, no. 3, Aug. 2009, pp. 299–325. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1353/lac.0.0080.

- ^"History".Chester County Free Public Library.Archivedfrom the original on 13 June 2010.Retrieved1 May2010.

- ^"The first county bookmobile in the US, Western Maryland Regional Library".whilbr.org.Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2006.Retrieved14 July2005.

- ^abcde"A History of the Bookmobile".PBS.19 July 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 13 March 2019.Retrieved21 October2022.

- ^Joanne E. Passet (1994)."Itinerating Libraries".InWayne A. Wiegandand Donald G. Davis (ed.).Encyclopedia of Library History.Taylor & Francis. pp. 315–317.ISBN978-0-8240-5787-9.

- ^abc"'Library on Wheels' Travels The Path Of America's First Bookmobile ".WBUR Here & Now.10 April 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 13 April 2018.Retrieved21 October2022.

- ^Washington County Free Library.First Annual Report for the Year ending October 1, 1902.

- ^Maryland State Archives. "Maryland Women's Hall of Fame".Washington County Free Library.

- ^Tabler, Dave (16 April 2018)."First bookmobile in the country".Appalachian History.Archived fromthe originalon 19 April 2018.Retrieved22 October2022.

- ^Levinson, Nancy Smiler (1 May 1991). "Takin' it to the Streets: The History of the Book Wagon".Library Journal.116(8): 43-45.

- ^Levinson, Nancy Smiler (1 May 1991). "Takin' it to the Streets: The History of the Book Wagon".Library Journal.116(8): 43-45.

- ^Susan B. Roumfort (1997). "Sarah Byrd Askew, 1877–1942". In Joan N. Burstyn (ed.).Past and Promise: Lives of New Jersey Women.Syracuse University Press. pp. 103–104.ISBN9780815604181.

- ^Ehling, Matt (30 June 2011)."The Hennepin County Library system – connecting past with present".MinnPost.No. Politics and Policy. Archived fromthe originalon 27 March 2018.Retrieved26 March2018.

- ^WPA (July 2012)."Packhorse Librarians in Kentucky, 1936–1943"(PDF).University of Kentucky.Archived(PDF)from the original on 21 February 2015.Retrieved2 April2014.

- ^Barbuschak, Christopher, Virginia Room Archivist/Librarian, City of Fairfax Regional Library, Statement by E-Mail, sent Thursday, 16 August 2018, 10:56:52 pm:[...] "in a history book entitled Fairfax County VA A History. On page 618, we found this sentence:" Herndon's Fortnightly Club established a library in 1889, and for many years this facility and the county's bookmobiles were the only library services available in the northwestern part of the county. "Fairfax County did not have bookmobiles until 1940." [...]

- ^Attig, Derek (12 April 2012)."National Bookmobile Day: Aggregation Edition".HASTAC.Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2015.Retrieved19 March2015.

- ^Berger, M. (1977). Reading, Roadsters, and Rural America.The Journal of Library History (1974–1987),12(1), 42–49.JSTOR25540714

- ^Sinclair, Frederick (1941). "War-time London's Library on Wheels".Wilson Library Bulletin.16:220–223.

- ^Bashaw, D. (2010)."On the road again: A look at bookmobiles, then and now"(PDF).Children & Libraries.Vol. 8, no. 1. pp. 32–35. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 9 November 2014.Retrieved12 November2014.

- ^Se connecter – ProQuest(in French),ProQuest875711389

- ^Want, Penny (1990). "The history and development of mobile libraries".Library Management.11(2): 5–14.doi:10.1108/EUM0000000000825.ProQuest57089094.

- ^Brena Smith; Michelle Jacobs (18 May 2010). "Libraries and patrons on the move: from bookmobiles to" m "libraries".Reference Services Review.38(2).doi:10.1108/rsr.2010.24038baa.002.ISSN0090-7324.

- ^Jeffrey Schnapp;Matthew Battles (2014).Library Beyond the Book.Harvard University Press.ISBN978-0-674-72503-4.

- ^"Bookmobile".The Internet Archive.

- ^Atwell, Ashleigh (28 February 2018)."Bed-Stuy Pop-Up Library Focuses On Black Women Writers".Bed-Stuy, NY Patch.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2018.Retrieved3 October2018.

- ^"National Bookmobile Day".ALA.17 February 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2015.Retrieved19 March2015.

- ^ALA."Bookmobiles".Pinterest.

- ^"First ever national library outreach day".ALA.22 February 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 25 February 2021.Retrieved14 March2021.

- ^"Kenya's children of the desert".Guardian Unlimited.1 December 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2008.Retrieved1 June2007.

- ^"Camel Library Service".Kenyan Camel Book Drive.Archivedfrom the original on 13 July 2014.Retrieved1 June2007.

- ^Hamilton, Masha (1 January 2007).The Camel Bookmobile: A Novel(1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins.ISBN9780061173486.LCCN2006041316.

- ^"Donkeys help provide Multi-media Library Services".IFLAnet (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions).25 February 2002.Retrieved26 March2018.

- ^"Perpustakaan Bergerak DBP mulakan perkhidmatan"(PDF).Pelita Brunei(in Malay). No. 31. 5 August 1970. pp. 1, 8.Retrieved14 July2021.

- ^"The Indonesian horse that acts as a library".BBC News.6 May 2015.

- ^ab"Mobile Section"(PDF).IFLA Newsletter.No. 1. Autumn 2002.Archived(PDF)from the original on 30 March 2017.Retrieved13 October2010.

- ^"The First's of Andhra Pradesh Library Association".

- ^Varma, P. Sujatha (15 April 2014)."He kept library movement afloat".The Hindu.

- ^"Bookmobile to Aid Heidelberg Readers".Age (Melbourne, Vic.: 1854 – 1954).1 May 1954. p. 9.Retrieved3 June2020.

- ^"Mobile Libraries".Lincolnshire County Council. Archived fromthe originalon 11 November 2013.Retrieved22 November2013.

- ^"Bibliobuses: La biblioteca móvil – Historia".Bibliotecas de la Comunidad de Madrid.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2018.Retrieved26 March2018.

- ^"La biblioteca móvil".Madrid.org.Comunidad de Madrid [city government]. 2015.Retrieved15 July2015.

- ^Kyöstiö, Antero (2004)."Kirjastoautohistoria".Kirjastot.fi(in Finnish).Retrieved30 July2019.

Suomen ensimmäinen liikkuva kirjasto toimi nykyisen Vantaan kaupungin, entisen Helsingin maalaiskunnan, alueella 1913–14.

- ^Johnson, Kirk (9 October 2014)."Homeless Outreach in Volumes: Books by Bike for 'Outside' People in Oregon".The New York Times.

- ^"Books on Bikes".The Seattle Public Library.Archived fromthe originalon 27 March 2018.Retrieved26 March2018.

- ^"Books on Bikes Helps Seattle Librarians Pedal To The Masses".NPR.org.Archivedfrom the original on 28 March 2018.Retrieved4 April2018.

- ^"Volusia County Libraries Have a Book Bike!"(PDF).Friends of the Daytona Beach Regional Library Newsletter.1 March 2016. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 March 2018.Retrieved26 March2018.

- ^"Luis Soriano".The Gallery of Heroes.CNN. November 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 1 June 2014.Retrieved1 April2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Finnell, Joshua (7 March 2009)."The Bookmobile: Defining the Information Poor".MSU Philosophy Club.An article on the history of the bookmobile in the US.

- King, Stephen (2011)."The Magic of the Bookmobile, Take Two".Read All Day.Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved19 March2015.

- Moore, Benita (1989).A Lancashire Year.Preston: Carnegie Publishing.Based on experiences while working on the Lancashire County Library mobile library service in the 1960s.

- Nix, Larry T. (ed.)."A Tribute to the Bookmobile".Library History Buff.USA.

- Ortwein, Orty (ed.)."Bookmobiles: a History".Wordpress.

- Stringer, Ian (2001).Britain's Mobile Libraries.Appleby-in-Westmorland: Trans-Pennine Publishing in association with Branch & Mobile Libraries Group of the Library Association.ISBN1-903016-15-0.

- Stringer, Ian (coordinated by) (2010).Mobile Library Guidelines.Paris:IFLA.ISBN978-90-77897-45-4.ISSN0168-1931.