Bratislava

Bratislava | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top:View of Bratislava; Financial district;Old Townstreets;Grassalkovich Palace;Blue Church;View of Old Town | |

| Nicknames: Beauty on the Danube, Little Big City | |

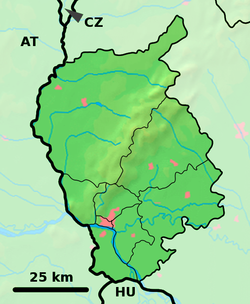

Location of Bratislava inSlovakia | |

| Coordinates:48°08′38″N17°06′35″E/ 48.14389°N 17.10972°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| First mentioned | 907 |

| Government | |

| •Mayor | Matúš Vallo |

| Area | |

| •Capital city | 367.584 km2(141.925 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 853.15 km2(329.40 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,053 km2(792.66 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 134 m (440 ft) |

| Population (2022[1]) | |

| •Metro | 728,370 |

| • Capital city census | 476,922 |

| • Capital city estimate | 660,000 |

| • Capital city estimate density | 1,297/km2(3,360/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Postal code | 8XX XX |

| Area code | 421 2 |

| Car plate | BA, BL, BT |

| Gross metropolitan product[2] | 2021 |

| – Total | €28 billion (US$33B) |

| – Per capita | €38,900 (US$46,007) |

| Website | bratislava.sk |

Bratislava(/ˌbrætɪˈslɑːvə/BRAT-iss-LAH-və,USalso/ˌbrɑːt-/BRAHT-,[3][4]Slovak:[ˈbracislaʋa]) (German:PressburgorPreßburg,German pronunciation:[ˈpʁɛsbʊʁk];Hungarian:Pozsony;Slovak:Prešporok), is thecapitaland largest city ofSlovakiaand the fourth largest of allcities on Danube river.Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, some sources estimate it to be more than 660,000—approximately 140% of the official figures.[5]Bratislava is in southwestern Slovakia at the foot of theLittle Carpathians,occupying both banks of theRiver Danubeand the left bank of theRiver Morava.BorderingAustriaandHungary,it is the only national capital to border twosovereign states.[6]

The city's history has been influenced by people of many nations and religions, includingAustrians,Bulgarians,Croats,Czechs,Germans,Hungarians,JewsandSlovaks.[7]It was the coronation site and legislative center and capital of theKingdom of Hungaryfrom 1563 to 1783;[8]elevenHungarian kingsand eight queens were crowned inSt Martin's Cathedral.MostHungarian parliament assemblieswere held here from the 17th century until theHungarian Reform Era,and the city has been home to many Hungarian, German and Slovak historical figures.

Today, Bratislava is thepolitical,culturalandeconomiccentre of Slovakia. It is the seat of theSlovak president,theparliamentand theSlovak Executive.It has several universities, and many museums, theatres, galleries and other cultural and educational institutions.[9]Many of Slovakia's large businesses and financial institutions have headquarters there.

Bratislava is57th largest cityin theEuropean Unionand 19th-richest region of the European Union by GDP (PPP) per capita.[10]GDP at purchasing power parity is about three times higher than in other Slovak regions.[11][12]Bratislava receives around one million tourists every year, mostly from the Czech Republic, Germany, and Austria.[13]

Etymology[edit]

The city received its contemporary name on 16 March 1919.[14]Until then, it was mostly known in English as "Pressburg" (from its German name,Preßburg), since after 1526, it was dominated mostly by the Habsburg monarchy and the city had a relevant ethnic German population. That is the term from which the pre-1919 Slovak (Prešporok) and Czech (Prešpurk) names are derived.[15]

The linguist Ján Stanislav believed the city's Hungarian name,Pozsony,to be attributed to the surname Božan, likely a prince who owned the castle before 950. Although the Latin name was also based on the same surname, according to research by the lexicologist Milan Majtán, the Hungarian version is not found in any official records from the time in which the prince would have lived. All three versions, however, were related to those found in Slovak, Czech and German: Vratislaburgum (905), Braslavespurch, and Preslavasburc (both 907).[16]

The medieval settlementBrezalauspurc(literally, 'Braslav's castle') is sometimes attributed to Bratislava, but theactual location of Brezalauspurc is under scholarly debate.The city's modern name is credited toPavol Jozef Šafárik's misinterpretation ofBraslavasBratislavin his analysis of medieval sources, which led him to invent the termBřetislaw,which later becameBratislav.[17]

During the revolution of 1918–1919, the name 'Wilsonov' or 'Wilsonstadt' (after US PresidentWoodrow Wilson) was proposed by American Slovaks, as he supported national self-determination. The nameBratislava,which had been used only by some Slovak patriots, became official in March 1919 with the aim that a Slavic name could support demands for the city to be part of Czechoslovakia.[18]

Other alternative names of the city in the past includeGreek:Ιστρόπολις,romanized:Istropolis(meaning 'DanubeCity', also used in Latin),Latin:Posonium,Romanian:Pojon,Croatian:Požun.

In older documents, confusion can be caused by the Latin formsBratislavia, Wratislaviaetc., which refer toWrocław,Poland, not Bratislava. The Polish city has a similar etymology despite spelling differences.[19]

History[edit]

The first known permanent settlement of the area began with theLinear Pottery Culture,around 5000 B.C. in theNeolithicera. About 200 B.C., theCelticBoiitribe founded the first significant settlement, a fortified town known as anoppidum.They also established amint,producing gold and silver coins known asbiatecs.[20]

The area fell underRomaninfluence from the 1st to the 4th century A.D. and was made part of theDanubian Limes,a border defence system.[21]The Romans introducedgrape growingto the area and began a tradition ofwinemaking,which survives to the present.[22]

TheSlavsarrived from the East between the 5th and 6th centuries during theMigration Period.[23]As a response to onslaughts byAvars,the local Slavic tribes rebelled and establishedSamo's Empire (623–658), the first known Slavic political entity. In the 9th century, the castles at Bratislava(Brezalauspurk)andDevín(Dowina)were important centres of the Slavic states: thePrincipality of NitraandGreat Moravia.[24]Scholars have debated the identification as fortresses of the two castles built in Great Moravia, based on linguistic arguments and because of the absence of convincingarchaeologicalevidence.[25][26]

The first written reference to a settlement named "Brezalauspurc" dates to 907 and is related to theBattle of Pressburg,during which aBavarianarmy was defeated by theHungarians.It is connected to the fall of Great Moravia, already weakened by its own inner decline[27]and under the attacks of the Hungarians.[28]The exact location of the battle remains unknown, and some interpretations place it west ofLake Balaton.[29]

In the 10th century, the territory of Pressburg (what would later becomePozsony county) became part of Hungary (called the "Kingdom of Hungary"from 1000). It developed as a key economic and administrative centre on the kingdom's frontier.[30]In 1052, German EmperorHenry IIIundertook a fifth campaign against theKingdom of Hungary,and besieged Pressburg without success, as the Hungarians sank his supply ships on theDanuberiver. This strategic position destined the city to be the site of frequent attacks and battles, but also brought it economic development and high political status. It was granted its first known "town privileges" in 1291 by the HungarianKing Andrew III,[31]and was declared afree royal townin 1405 byKingSigismund.In 1436, he authorized the town to use itsown coat of arms.[32]

The Kingdom of Hungary was defeated by theOttoman Empirein theBattle of Mohácsin 1526. The Ottomans besieged and damaged Pressburg, but failed to conquer it.[33]Owing to Ottoman advances into Hungarian territory, the city was designated the new capital of Hungary in 1536, after becoming part of theHabsburg monarchyand marking the beginning of a new era. The city became a coronation town and the seat of kings, archbishops (1543), the nobility and all major organisations and offices. Between 1536 and 1830, eleven Hungarian kings and queens were crowned atSt. Martin's Cathedral.[34]

The 17th century was marked by anti-Habsburg uprisings, fighting with the Ottomans, floods,plaguesand other disasters, which diminished the population.[35]Great epidemics were spreading in Bratislava in 1541–1542, 1552–1553, 1660–1665 and 1678–1681. Aterrible outbreakof 1678–1681 left approximately 11,000 casualties among Bratislava’s residents (city population was in that time around 30,000 people). The lastplague outbreakof Bratislava was between the years 1712–1713.[36]

Pressburg flourished during the 18th-century reign of QueenMaria Theresa,[37]becoming the largest and most important town in theKingdom of Hungary.[38]The population tripled; many new palaces,[37]monasteries, mansions, and streets were built, and the city was the centre of social and cultural life of the region.[39]Wolfgang Amadeus Mozartgave a concert in 1762 in thePálffy Palace.Joseph Haydnperformed in 1784 in theGrassalkovich Palace.Ludwig van Beethovenwas a guest in 1796 in theKeglevich Palace.[40][41]

The city started to lose its importance under the reign of Maria Theresa's sonJoseph II,[37]especially after thecrown jewelswere taken toViennain 1783 in an attempt to strengthen the relations between Austria and Hungary. Many central offices subsequently moved toBuda,followed by a large segment of the nobility.[42]The first newspapers in Hungarian and Slovak were published here:Magyar hírmondóin 1780, andPresspurske Nowinyin 1783.[43]In the course of the 18th century, the city became a centre for theSlovak national movement.[citation needed]

The city's 19th-century history was closely tied to the major events in Europe. ThePeace of PressburgbetweenAustrian EmpireandFrench Empirewas signed here in 1805.[44]Devín Castlewas ruined byNapoleon's French troops during an invasion of 1809.[45]In 1825 theHungarian National Learned Society(the present Hungarian Academy of Sciences) was founded in Pressburg using a donation fromIstván Széchenyi.In 1843 Hungarian was proclaimed the official language in legislation, public administration, and education by the Diet in the city.[46]

As a reaction to theRevolutions of 1848,Ferdinand Vsigned the so-calledApril laws,which included the abolition ofserfdom,at thePrimate's Palace.[47]The city chose the revolutionary Hungarian side, but was captured by the Austrians in December 1848.[48]

Industry developed rapidly in the 19th century. The firsthorse-drawn railwayin the Kingdom of Hungary,[49]from Pressburg to Szentgyörgy (Svätý Jur), was built in 1840.[50]A new line to Vienna usingsteam locomotiveswas opened in 1848, and a line toPestin 1850.[51]Many new industrial, financial and other institutions were founded; for example, the first bank in present-day Slovakia was founded in 1842.[52]The city's first permanent bridge over the Danube,Starý most(Old Bridge), was built in 1891.[53]Between the years 1867-1918, the territory of Pressburg became part ofAustro-Hungarian Empire.

BeforeWorld War I,the city had a population that was 42% German, 41% Hungarian and 15% Slovak (1910 census). The first post war census in 1919 declared the city's ethnic composition at 36% German, 33% Slovak and 29% Hungarian but this may have reflected changing self-identification, rather than an exchange of peoples. Many people were bi- or trilingual and multicultural.[citation needed]

AfterWorld War I,begandissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.U.S. presidentWoodrow Wilsonand the United States played a major role in the establishment of the newCzechoslovak state.American Slovaks proposed rename the city “Wilsonovo mesto” (Wilson City), after Woodrow Wilson.[54]

On 28 October 1918,Czechoslovakiawas proclaimed, but its borders were not settled for several months.[55]The dominant Hungarian and German population tried to prevent annexation of the city to Czechoslovakia and declared it afree city,[56]while the Hungarian Prime Minister Károlyi protested against the Czech invasion. The Slovak National Assembly meanwhile called it a"defensive action of the Slovaks themselves, to end the anarchy caused by the flight of the Hungarians."[57]TheAllies of World War Idrew a provisional demarcation line, this was revealed to the Hungarian government on December 23, in the document known as theVix Note.TheCzechoslovak Legionarrived from Italy, began to advance on 30 December and by 2 January 1919, all important civil and military buildings were in Czechoslovak hands.[58]It was the beginning of the conflict, which later continued asHungarian–Czechoslovak War.The city became the seat of Slovakia's political organs and organizations and became Slovakia's capital on 4 February.[59]

On March 27, 1919, the name Bratislava was officially adopted for the first time to replace the previous Slovak name Prešporok.[60]

At the beginning of August 1919, Czechoslovakia got permission to correct the borders for the strategic reasons, mainly to secure the port and to prevent a potential attack of theHungarian Armyon the town. On the night of 14 August 1919 barefoot Czechoslovak soldiers silently climbed to the Hungarian side of theStarý most(Old Bridge), captured the guards and annexedPetržalka(currently part of Bratislava's5th district) without a fight.[61]TheParis Peace Conferenceassigned the area toCzechoslovakiawith the aim of creating abridgeheadfor the newly created Czechoslovak state for controlling the Danube.

Left without any protection after the retreat of the Hungarian army, many Hungarians were expelled or fled.[62]Czechs and Slovaks moved their households to Bratislava. Education inHungarianandGermanwas radically reduced in the city.[63]By the 1930Czechoslovakcensus,the Hungarian population of Bratislava had decreased to 15.8% (see theDemographics of Bratislavaarticle for more details).

In 1938,Nazi Germanyannexed neighbouring Austria in theAnschluss;on 10 October 1938 on the basis of theMunich Agreementit also annexed (still-separate from Bratislava)PetržalkaandDevínboroughs on ethnic grounds, as these had many ethnic Germans.[64][65]Petržalka was renamedEngerau.TheStarý most(Old Bridge) became a border bridge betweenCzechoslovakiaand Nazi Germany.[citation needed]

Bratislava was declared the capital of thefirst independent Slovak Republicon March 14, 1939, but the new state quickly fell under Nazi influence. In 1941–1942 and 1944–1945, the new Slovak government cooperated in deporting most of Bratislava's approximately 15,000 Jews;[66]they were transported toconcentration camps,where most were killed or died before the end of the war in theHolocaust.[67]

Bratislava, occupied by German troops, was many times bombarded by theAllies.Major air raid included the bombing of Bratislava and its refineryApolloon June 16, 1944 by AmericanB-24 bombersof theFifteenth Air Forcewith 181 victims[68]Bombardment groupattacked in four waves with overall 158 planes. On 4 April 1945, Bratislava was taken by troops of theSoviet Red Army2nd Ukrainian FrontduringBratislava–Brno offensive.[64][69]At the end of World War II, most of Bratislava's ethnic Germans were evacuated by the German authorities. A few returned after the war, but were soon expelled without their properties under theBeneš decrees,[70]part of a widespreadexpulsion of ethnic Germansfrom eastern Europe.

After World War II,Slovak Republiclost its so-called independence and was reunified again with the Czech Republic asCzechoslovak Republic,Petržalka (currently part of Bratislava's5th district) and Devín (currently part of Bratislava's4th district) was returned to Czechoslovakia. Furthermore, after signing thePeace Treaty of Parison 10 February 1947, threeHungarianvillages, namelyHorvátjárfalu(Jarovce),Oroszvár(Rusovce), andDunacsún(Čunovo) situated south of Bratislava were transferred to Czechoslovakia, in order to form the so-called "Bratislava bridgehead"(currently all three of them are part of Bratislava's5th district).

After theCommunist Partyseized power inCzechoslovakiain February 1948, the city became part of theEastern Bloc.The city annexed new land, and the population rose significantly, becoming 90% Slovak.[citation needed]

Large residential areas consisting of high-riseprefabricatedpanel buildings,such as those in thePetržalkaorDúbravkaborough, were built. The Communist government also built several new grandiose buildings, such as theSlovak Radio Building,SlavínorKamzík TV Tower.A quarter of Bratislava’sOld Townwas demolished in the late 1960s for a single project:the bridge of the Slovak National Uprising.To make space for this development, much of the city’s centuries-old, historical Jewish quarter was razed, including the 19th-century Moorish-styled Neolog Synagogue.[71]

In 1968, after the unsuccessfulCzechoslovak attemptto liberalise the Communist regime, the city was occupied byWarsaw Pacttroops. Shortly thereafter, it became capital of theSlovak Socialist Republic,one of the two states of thefederalizedCzechoslovakia.

Bratislava's dissidents anticipated the fall of Communism with theBratislava candle demonstrationin 1988, and the city became one of the foremost centres of the anti-CommunistVelvet Revolutionin 1989.[72]

The end of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia in 1989 was followed once again by the country's dissolution, this time into twosuccessor states.Czechoslovak Socialist Republicrenamed asCzech and Slovak Federative Republic,the word "socialist" was dropped in the names of the two republics within the federation, the Slovak Socialist Republic renamed asSlovak Republic.

In 1993, Bratislava became second time the capital of the newly formed independentSlovak Republic,following theVelvet Divorce.[73]

Geography[edit]

Bratislava is situated in southwestern Slovakia, within theBratislava Region.Its location on the borders with Austria and Hungary makes it theonly national capital that borders two countries.It is only 18 kilometres (11.2 mi) from the border with Hungary and only 60 kilometres (37.3 mi) from the Austrian capitalVienna.[74]

The city has a total area of 367.58 square kilometres (141.9 sq mi), making it the second-largest city in Slovakia by area (after the township ofVysoké Tatry).[75]Bratislava straddles theDanubeRiver, along which it had developed and for centuries the chief transportation route to other areas. The river passes through the city from the west to the southeast. TheMiddle Danubebasin begins atDevín Gatein western Bratislava. Other rivers are theMorava River,which forms the northwestern border of the city and enters the Danube at Devín, theLittle Danube,and theVydrica,which enters the Danube in the borough ofKarlova Ves.

TheCarpathianmountain range begins in city territory with theLittle Carpathians(Malé Karpaty). TheZáhorieandDanubianlowlands stretch into Bratislava. The city's lowest point is at the Danube's surface at 126 metres (413 ft)above mean sea level,and the highest point isDevínska Kobylaat 514 metres (1,686 ft). The average altitude is 140 metres (460 ft).[76]

Climate[edit]

Bratislava has recently shifted into thehumid subtropical climateunderKöppen–Geiger climate classification(Cfa), and is classified as temperate oceanic climate underTrewartha climate classification(DOak), It is in USDAPlant Hardiness Zone7b[77]with a mean annual temperature of around 11.1 °C (52.0 °F), an average temperature of 22.0 °C (71.6 °F) in the warmest month and 0.3 °C (32.5 °F) in the coldest month, four distinct seasons[78]and precipitation spread rather evenly throughout the year. It is often windy with a marked variation between hot summers and cold, humid winters. There also can sometimes be a significant difference in weather, between the parts of the city. Bratislava, just like any other city, has anurban heat islandeffect, but there is no weather station directly in the urban core, so the temperature there can be slightly higher than the official weather station reports. The city is in one of the warmest and driest parts of Slovakia.[79]

Recently, the transitions from winter to summer and summer to winter have been rapid, with short autumn and spring periods. Snow occurs less frequently than previously.[78]Extreme temperatures (1981–2013) – record high: 39.4 °C (102.9 °F),[80]record low: −24.6 °C (−12.3 °F). Some areas, particularly Devín andDevínska Nová Ves,are vulnerable to floods from the Danube and Morava rivers.[81]New flood protection has been built on both banks.[82]

| Climate data forBratislava Airport(1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

30.3 (86.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

38.2 (100.8) |

39.4 (102.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

28.0 (82.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

17.9 (64.2) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.6 (−12.3) |

−24.6 (−12.3) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−20.3 (−4.5) |

−24.6 (−12.3) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 37.4 (1.47) |

32.9 (1.30) |

36.8 (1.45) |

35.9 (1.41) |

58.6 (2.31) |

59.2 (2.33) |

61.8 (2.43) |

60.5 (2.38) |

58.6 (2.31) |

43.6 (1.72) |

46.2 (1.82) |

42.7 (1.68) |

574.3 (22.61) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.2 | 11.4 | 11.7 | 9.2 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 11.5 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 11.2 | 12.5 | 13.6 | 136.1 |

| Average snowy days | 11.2 | 8.7 | 5.8 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 4.1 | 8.6 | 39.8 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 80.9 | 74.7 | 67.5 | 61.0 | 62.8 | 62.0 | 60.5 | 62.3 | 69.2 | 76.8 | 81.9 | 83.2 | 70.2 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 65.5 | 99.3 | 153.7 | 218.6 | 258.1 | 269.4 | 286.5 | 273.3 | 194.5 | 134.6 | 69.5 | 51.9 | 2,074.9 |

| Source 1:World Meteorological Organisation[83][84] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SHMI (extremes, 1951-present)[85] | |||||||||||||

Location[edit]

Cityscape and architecture[edit]

The cityscape of Bratislava is characterized by medieval towers and grandiose 20th-century buildings, but it underwent profound changes in a construction boom at the start of the 21st century.[86]

Most historical buildings are concentrated in theOld Town.Bratislava's Town Hallis a complex of three buildings erected in the 14th–15th centuries and now hosts theBratislava City Museum.Michael's Gateis the only gate that has been preserved from themedieval fortifications,and it ranks among the oldest of the town's buildings;[87]the narrowest house in Europe is nearby.[88]The University Library building, erected in 1756, was used by theDiet of the Kingdom of Hungaryfrom 1802 to 1848.[89]Much of the significant legislation of theHungarian Reform Era(such as the abolition ofserfdomand the foundation of theHungarian Academy of Sciences) was enacted there.[89]

The historic centre is characterized by manybaroquepalaces. TheGrassalkovich Palace,built around 1760, is now the residence of the Slovak president, and the Slovak government now has its seat in the formerArchiepiscopal Palace.[90]In 1805, diplomats of emperorsNapoleonandFrancis IIsigned the fourthPeace of Pressburgin thePrimate's Palace,after Napoleon's victory in theBattle of Austerlitz.[91]Some smaller houses are historically significant; composerJohann Nepomuk Hummelwas born in an 18th-century house in the Old Town.

Notable cathedrals and churches include theGothicSt. Martin's Cathedralbuilt in the 13th–16th centuries, which served as the coronation church of the Kingdom of Hungary between 1563 and 1830.[92]TheFranciscan Church,dating to the 13th century, has been a place of knighting ceremonies and is the oldest preserved sacral building in the city.[93]TheChurch of St. Elizabeth,better known as the Blue Church due to its colour, is built entirely in theHungarian Secessioniststyle. Bratislava has one surviving functioningsynagogue,out of the three major ones existing before theholocaust.

A curiosity is the underground (formerly ground-level) restored portion of the Jewish cemetery where 19th-century RabbiMoses Soferis buried, located at the base of the castle hill near the entrance to a tram tunnel.[94]The only military cemetery in Bratislava isSlavín,unveiled in 1960 in honour ofSoviet Armysoldiers who fell during the liberation of Bratislava in April 1945. It offers a view of the city and theLittle Carpathians.[95][96]

Other prominent 20th-century structures include theMost Slovenského národného povstania(Bridge of the Slovak national uprising) across theDanubefeaturing aUFO-liketower restaurant,Slovak Radio's inverted-pyramid-shaped headquarters, and the uniquely designedKamzík TV Towerwith an observation deck and rotating restaurant. In the early 21st century, new edifices have transformed the traditional cityscape. At the beginning of the 21st century, a construction boom has spawned new public structures,[97]such as theMost Apolloand a new building of theSlovak National Theatre,[98]as well as privatereal-estate development.[99]

Bratislava Castle[edit]

One of the most prominent structures in the city isBratislava Castle(Bratislavský hrad), situated on a plateau 85 metres (279 ft) above the Danube. The castle hill site has been inhabited since the transitional period between theStoneandBronzeages[100]and has been theacropolisof aCeltictown, part of theRomanlimesRomanus, a huge Slavic fortified settlement, and a political, military and religious centre forGreat Moravia.[101]A stonecastlewas not constructed until the 10th century, when the area was part of theKingdom of Hungary,however, in the9th centuryapre-romanesque stone basilica,was standing in the area of the hillfort.

The castle was converted into aGothicanti-Hussitefortress underSigismund of Luxemburgin 1430, became aRenaissancecastle in 1562,[102]and was rebuilt in 1649 in thebaroquestyle. UnderQueenMaria Theresa,the castle became a prestigious royal seat. In 1811, the castle was inadvertently destroyed by fire and lay in ruins until the 1950s,[103]when it was rebuilt mostly in its former Theresian style. In the 1940s, it was planned to demolish the castle ruins and replace them with a new university complex. However, it was never realised, and in the 1960s, reconstruction began. Nowadays, it serves ceremonial purposes and as a historical museum of theSlovak National Museum.

Devín Castle[edit]

The ruined and recently renovatedDevín Castleis in the borough ofDevín,on top of a rock where theMorava River,which forms the border between Austria and Slovakia, enters the Danube. It is one of the most important Slovak archaeological sites and contains a museum dedicated to its history.[105]Due to its strategic location, Devín Castle was a very important frontier castle ofGreat Moraviaand the early Hungarian state. It was destroyed by Napoleon's troops in 1809. It is an important symbol of Slovak and Slavic history.[106]

Rusovce[edit]

Rusovce mansion,with itsEnglish park,is in the Rusovce borough. The house was originally built in the 17th century and was turned into an Englishneo-Gothic-style mansion in 1841–1844.[107]The borough is also known for the ruins of the Roman military campGerulata,part of limes Romanus, a border defence system. Gerulata was built and used between the 1st and 4th centuriesAD.[108]

Parks and lakes[edit]

Due to its location in the foothills of theLittle Carpathiansand itsriparian vegetationon the Danubianfloodplains,Bratislava has forests close to the city centre. The total amount of public green space is 46.8 square kilometres (18.1 sq mi), or 110 square metres (1,200 sq ft) per inhabitant.[109] The largest city park is Horský park (literally, Mountainous Park), in the Old Town.Bratislavský lesný park(Bratislava Forest Park) is located in the Little Carpathians and includes many locales popular among visitors, such asŽelezná studienkaandKoliba.The Forest Park covers an area of 27.3 square kilometres (10.5 sq mi), of which 96% is forested mostly withoakand mixed oak/hornbeamforest, and contains original flora and fauna such asEuropean badgers,red foxes,wild boarandredandroe deer.On the right bank of the Danube, in the borough of Petržalka, isJanko Kráľ Parkfounded in 1774–76.[110]A new city park is planned for Petržalka between the Malý Draždiak and Veľký Draždiak lakes.[99]

Bratislava's zoological parkis located inMlynská dolina,near the headquarters ofSlovak Television.The zoo, founded in 1960, currently houses 152 species of animals, including the rarewhite lionandwhite tiger.The Botanical Gardens, which belong toComenius University,can be found on the Danube riverfront and house more than 120 species of domestic and foreign origin.[111]

The city has a number of natural and human-made lakes, most of which are used for recreation. Examples include Štrkovec lake inRužinov,Kuchajda inNové Mesto,Zlaté Pieskyand theVajnorylakes in the north-east, andRusovcelake in the south, which is popular withnudists.[112]

Demographics[edit]

| District | Population | Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bratislava I–V | 475,577 | Slovaks | 407,358 |

| Bratislava I | 46,432 | Hungarians | 11,167 |

| Bratislava II | 112,001 | Czechs | 5,031 |

| Bratislava III | 76,694 | Ukrainians | 1524 |

| Bratislava IV | 105,154 | Germans | 750 |

| Bratislava V | 122,296 | Other/undeclared | 47,239 |

From the city's origin until the 19th century, Germans were the dominant ethnic group.[15]By the end ofWorld War I,42% of the population of Pressburg spoke German as their native language, 40% Hungarian, and 15% Slovak.[15]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 194,225 | — |

| 1960 | 238,519 | +22.8% |

| 1970 | 282,043 | +18.2% |

| 1980 | 380,259 | +34.8% |

| 1991 | 442,197 | +16.3% |

| 2001 | 428,672 | −3.1% |

| 2011 | 411,228 | −4.1% |

| 2021 | 475,503 | +15.6% |

| Source:[114][115] | ||

After the formation of theCzechoslovak Republicin 1918, Bratislava remained a multi-ethnic city, but with a different demographic trend. Due toSlovakization,[116][117]the proportion of Slovaks and Czechs increased in the city, while the proportion of Germans and Hungarians fell. In 1938, 59% of the population were Slovaks or Czechs, while Germans represented 22% and Hungarians 13% of the city's population.[118]The creation of the first Slovak Republic in 1939 brought other changes, most notably the expulsion of many Czechs and the deportation or flight of the Jews during theHolocaust.[15][119]In 1945, most of the Germans were evacuated. After the restoration of Czechoslovakia, theBeneš decrees(partly revoked in 1948) collectively punished ethnic German and Hungarian minorities by expropriation and deportation to Germany, Austria, and Hungary for their alleged collaborationism with Nazi Germany and Hungary against Czechoslovakia.[67][120][121]

The city thereby obtained its clearly Slovak character.[67]Hundreds of citizens were expelled during the communist oppression of the 1950s, with the aim of replacing "reactionary" people with the proletarian class.[15][67]Since the 1950s, the Slovaks have been the dominant ethnicity in the town, making up around 90% of the city's population.[15]

Politics[edit]

Bratislava is the seat of theSlovak parliament,presidency,ministries, supreme court (Slovak:Najvyšší súd), andcentral bank.It is the seat of theBratislava Regionand, since 2002, also of the Bratislava Self-Governing Region. The city also has many foreignembassiesandconsulates.

The current local government (Mestská samospráva)[122]structure has been in place since 1990.[123]It is composed of amayor(primátor),[124]a city board (Mestská rada),[125]acity council(Mestské zastupiteľstvo),[126]city commissions(Komisie mestského zastupiteľstva),[127]and a citymagistrate's office (Magistrát).[128]

The mayor, based at thePrimate's Palace,is the city's top executive officer and is elected to a four-year term of office. The current mayor of Bratislava isMatúš Vallo,who won theelectionheld on October 29, 2022, as an independent candidate. The city council is the city's legislative body, responsible for issues such as budget, local ordinances,city planning,road maintenance, education, and culture.[129]

City Council[edit]

The Bratislava City Council is the legislature of the City of Bratislava. It has 45 members. The Council usually convenes once a month and consists of 45 members elected to four-year terms concurrent with the mayor's. Many of the council's executive functions are carried out by the city commission at the council's direction.[127]The city board is a 28-member body composed of the mayor and his deputies, the borough mayors, and up to ten city council members. The board is an executive and supervisory arm of the city council and also serves in an advisory role to the mayor.[125]

Administration[edit]

Administratively, Bratislava is divided into fivedistricts:Bratislava I (the city centre), Bratislava II (eastern parts), Bratislava III (north-eastern parts), Bratislava IV (western and northern parts) and Bratislava V (southern parts on the right bank of the Danube, including Petržalka, the most densely populated residential area inCentral Europe).[130]

For self-governance purposes, the city is divided into 17 boroughs, each of which has its own mayor (starosta) and council. The number of councillors in each depends on the size and population of the borough.[131]Each of the boroughs coincides with the city's 20cadastral areas,except for two cases: Nové Mesto is further divided into the Nové Mesto and Vinohrady cadastral areas and Ružinov is divided into Ružinov, Nivy and Trnávka. Further unofficial division recognizes additional quarters and localities.

| District | Borough | Map |

|---|---|---|

| Bratislava I |

| |

| Bratislava II | ||

| Bratislava III | ||

| Bratislava IV | ||

| Bratislava V | ||

Economy[edit]

TheBratislava Regionis the wealthiest and most economically prosperous region in Slovakia, despite being the smallest by area and having the third smallest population ofthe eight Slovak regions.It accounts for about 26% of the SlovakGDP.[132]According toGDPper capita, Bratislava is the 19th-richest region in the European Union in 2023.[133]The unemployment rate in Bratislava was 2,38% in June 2023.[134]The average monthly salary in the Bratislava region in 2024 was €2,101.[135]

Many governmental institutions and private companies have their headquarters in Bratislava. More than 75% of Bratislava's population works in theservice sector,mainly composed oftrade,banking,IT,telecommunications,andtourism.[136]TheBratislava Stock Exchange(BSSE), the organiser of the public securities market, was founded on 15 March 1991.[137]

Companies operating predominantly in Bratislava with the highest value added according to the 2018TrendTop 200 ranking, include theVolkswagen Bratislava Plant,Slovnaft refinery (MOL),Eset(software developer), Asseco (software company), PPC Power (producer of heat and steam) and Trenkwalder personnel agency.[138]

Volkswagen Grouptook over and expanded theBAZfactory in 1991, and has since considerably expanded production beyond originalSkoda Automodels.[139]Currently,[timeframe?]68% of production is focused onSUVs:Audi Q7;VW Touareg;as well as the body and under-chassis of thePorsche Cayenne.Since 2012, production has also included theVolkswagen up!,SEAT MiiandSkoda Citigo.[140]

In recent years,serviceandhigh-tech-oriented businesses have prospered in Bratislava. Many global companies, includingIBM,Dell,Lenovo,AT&T,SAP,Amazon,Johnson Controls,Swiss ReandAccenture,have builtoutsourcingand service centres here.[141]Reasons for the influx ofmulti-national corporationsinclude proximity to Western Europe, skilled labour force and the high density of universities and research facilities.[142]Also Slovak IT companies includingESET,SygicandPixel Federationhave headquarters in Bratislava.

Other large companies and employers with headquarters in Bratislava includeSlovak Telekom,Orange Slovensko,Slovenská sporiteľňa,Tatra banka,Doprastav,Hewlett-PackardSlovakia,Slovnaft,HenkelSlovensko,[143]Slovenský plynárenský priemysel,Kraft FoodsSlovakia,Whirlpool Slovakia,Železnice Slovenskej republiky,AeroMobil,andTescoStores Slovak Republic.

TheSlovak economy'sstrong growth in the 2000s has led to a boom in the construction industry, and several major projects have been completed or are planned in Bratislava.[97]Areas attracting developers include theDanuberiverfront, where two major projects are already finished: River Park in the Old Town, andEuroveanear the Apollo Bridge.[144][145]Other locations under development include the areas around the main railway and bus stations, the former industrial zone near the Old Town and in the boroughs of Petržalka, Nové Mesto and Ružinov.[130][146][147]In 2010, the city had a balanced budget of €277 million, with one fifth used for investment.[148]Bratislava holds shares in 17 companies directly, including the city's public transport companyDopravný podnik Bratislava,thewaste collection and disposalcompany named OLO (Odvoz a likvidácia odpadu), and the water utility.[149]The city also manages municipal organisations such as the city police (Mestská polícia),Bratislava City MuseumandZOO Bratislava.[150]

Tourism[edit]

In 2022 a total of 927,950 people came to visit Bratislava and spent there 1,719,409 nights.[151]These were most commonly 65% foreigners. Bratislava attracts predominantly visitors from the neighboring and nearby countries - Czech Republic, Germany, Austria and Poland. The top 5 is closed by visitors from the UK. Bratislava offered 272 accommodation facilities with 10,338 rooms in 2022.[151]A considerable share of visits is made by those who visit Bratislava for a single day, but their exact number is not available.

Among other factors, the growth oflow-cost airlineflights to Bratislava, led byRyanair,has led to conspicuousstag parties,primarily from the UK. While these are a boom to the city's tourism industry, cultural differences andvandalismhave led to concern by local officials.[152]Reflecting the popularity of rowdy parties in Bratislava in the early to mid-2000s, the city was a setting in the 2004 comedy filmEurotrip,which was actually filmed in the city ofPrague,the Czech Republic.

Shopping[edit]

Bratislava has eight major shopping centres:Aupark,Avion Shopping Park,Bory Mall,Central,Eurovea,Nivy Centrum,Vivo!(formerly Polus City Center) and Shopping Palace.

A month before Christmas, theMain Squarein Bratislava is illuminated by a Christmas tree and the Christmas market stalls are officially opened. Around 100 booths are opened every year. It is opened most of the day as well as in the evening.

Culture[edit]

Bratislava is the cultural heart of Slovakia. Owing to its historical multi-cultural character, local culture is influenced by various ethnic and religious groups, including Germans, Slovaks, Hungarians, and Jews.[153]Bratislava enjoys numerous theatres, museums, galleries, concert halls, cinemas, film clubs, and foreign cultural institutions.[154]

Performing arts[edit]

Bratislava is the seat of theSlovak National Theatre,housed in two buildings.[155]The first is aNeo-Renaissancetheatre building situated in the Old Town at the end ofHviezdoslav Square.The new building, opened to the public in 2007, is on the riverfront.[98][155]The theatre has three ensembles: opera, ballet and drama.[155]Smaller theatres include theNew Scene Theatre,theAstorka Korzo '90 Theatre,theArena Theatre,the L+S Studio, the Naive Theatre of Radošina and the Bratislava Puppet Theatre.

Music in Bratislava flourished in the 18th century and was closely linked to Viennese musical life.Mozartvisited the town at the age of six. Among other notable composers who visited or lived in the town wereHaydn,Liszt,[156]BartókandBeethoven.It is also the birthplace of the composersJohann Nepomuk Hummel,Ernő Dohnányi,andFranz Schmidt.Bratislava is home to both theSlovak PhilharmonicOrchestra and thechamber orchestra,Capella Istropolitana.The city hosts several annual festivals, such as theBratislava Music FestivalandBratislava Jazz Days.[157]During the summer, various musical events take place as part of the Bratislava Cultural Summer atBratislava Castle.Apart from musical festivals, it is possible to hear music ranging from underground to well known pop stars.[158]

Bratislava is home to two of Slovakia's national folk dance ensembles, Lúčnica and Slovenský ľudový umelecký kolektív (SĽUK).[159][160][161]

Museums and galleries[edit]

TheSlovak National Museum(Slovenské národné múzeum), founded in 1961, has its headquarters in Bratislava on the riverfront in the Old Town, along with the Natural History Museum, which is one of its subdivisions. It is the largest culturalinstitutionin Slovakia, and manages 16 specialized museums in Bratislava and beyond.[162]TheBratislava City Museum(Múzeum mesta Bratislavy), established in 1868, is the oldest museum in continuous operation in Slovakia.[163]Its primary goal is to chronicle Bratislava's history in various forms from the earliest periods using historical and archaeological collections. It offers permanent displays in eight specialised museums.

TheSlovak National Gallery,founded in 1948, offers the most extensive network of galleries in Slovakia. Two displays in Bratislava are next to one another atEsterházy Palace(Esterházyho palác) and the Water Barracks (Vodné kasárne) on the Danube riverfront in the Old Town. TheBratislava City Gallery,founded in 1961, is the second-largest Slovak gallery of its kind. The gallery offers permanent displays atPálffy Palace(Pálffyho palác) andMirbach Palace(Mirbachov palác), in the Old Town.[164]Danubiana Art Museum, one of the youngest art museums in Europe, is nearČunovowaterworks.[165]

Media[edit]

As the national capital, Bratislava is home to national and many local media outlets. Notable TV stations based in the city includeRadio and Television of Slovakia(Rozhlas a televízia Slovenska),Markíza,JOJandTA3.RTVSradio'sheadquartershas its seat in the centre, and many Slovak commercial radio stations are based in the city. National newspapers based in Bratislava includeSME,Pravda,Nový čas,Hospodárske novinyand the English-languageThe Slovak Spectator.Two news agencies are headquartered there: theNews Agency of the Slovak Republic(TASR, Tlačová agentúra Slovenskej republiky) and the Slovak News Agency (SITA, Slovenská tlačová agentúra).

Sport[edit]

Varioussportsand sports teams have a long tradition in Bratislava, with many teams and individuals competing in Slovak and internationalleaguesandcompetitions.

Footballis currently represented by the only club playing in the top Slovak football league, theFortuna Liga.ŠK Slovan Bratislava,founded in 1919, has its home ground at theTehelné polestadium. ŠK Slovan is the most successful football club in Slovak history, being the only club from the formerCzechoslovakiato win the European football competition theCup Winners' Cup,in 1969.[166] FC Petržalka akadémiais the oldest of Bratislava's football clubs, founded in 1898, and is based atStadium FC Petržalka 1898in Petržalka (formerly atPasienkyin Nové Mesto andŠtadión Petržalkain Petržalka). They are currently the only Slovak team to win at least one match in theUEFA Champions Leaguegroup stage, with a 5–0 win overCeltic FCin the qualifying round being the most well-known, alongside a 3–2 win overFC Porto.Before thenFC Košicein the 1997–98 season lost all six matches, despite being the first Slovak side since independence to play in the competition.

In 2010 Artmedia were relegated from the Corgon Liga under their new name of MFK Petržalka, finishing 12th and bottom. FC Petržalka akadémia currently competes in5. ligaafter bankruptcy in summer 2014. Another known club from the city isFK Inter Bratislava.Founded in 1945, they have their home ground atStadium ŠKP Inter DúbravkainDúbravka,(formerly at Štadión Pasienky) and currently plays in the3. liga.There are many more clubs with long tradition and successful history despite the lack of success in last years, e.g.LP DominoBratislava currently playing in4. liga;FK RačaBratislava competing in the3. ligaas well as Inter;FK ŠKP Inter Dúbravka Bratislava,following ŠKP Devín (successful team from the 1990s) and partially following the original Inter (original Inter bankrupted in 2009, sold theCorgoň Ligalicense toFK Senicaand legally merged with FC ŠKP Dúbravka; current Inter has taken over the tradition, name, colours, fans, etc., but legally is no successor of the original Inter);FC Tatran Devín,the club that was successful mostly at youth level and merged with ŠKP Bratislava in 1995;MŠK Iskra Petržalka,playing under the nameŠK Iskra Matadorfix Bratislavain the former 1st League (today2nd) in1997/98.

Bratislava is home to three winter sports arenas:Ondrej NepelaWinter Sports Stadium,V. DzurillaWinter Sports Stadium, andDúbravkaWinter Sports Stadium. TheHC Slovan Bratislavaice hockey team has represented Bratislava from the2012–13 seasonin theKontinental Hockey League.Slovnaft Arena,a part ofOndrej NepelaWinter Sports Stadium, is home to HC Slovan. TheIce Hockey World Championshipsin 1959 and 1992 were played in Bratislava, and the2011 World Championshipwere held in Bratislava andKošice,for which a new arena was built.[167]The city also played host to the World Championship in 2019.

TheČunovo Water Sports Centreis awhitewater slalomandraftingarea, close to theGabčíkovo dam.It hosts several international and nationalcanoeandkayakcompetitions annually.

In 1966, Bratislava named its new multi-sports stadium after tennis playerLadislav Hecht.[168][169]

The National Tennis Centre, which includesAegon Arena,hosts various cultural, sporting and social events. SeveralDavis Cupmatches have been played there, including the2005 Davis Cupfinal. The city is represented in the top Slovak leagues in women's and men'sbasketball,women'shandballandvolleyball,and men'swater polo.The Devín–Bratislava National run is the oldest athletic event in Slovakia,[170]and the Bratislava City Marathon has been held annually since 2006. Arace trackis located inPetržalka,wherehorse racinganddog racingevents anddog showsare held regularly.

Bratislava is also the centre ofrugby union in Slovakiaandmotorcycle speedwaypreviously existed at several venues throughout the city.[171]

Education and science[edit]

The first university in Bratislava, in theKingdom of Hungary(and also in the territory of present-day Slovakia) wasUniversitas Istropolitana,founded in 1465 by KingMatthias Corvinus.It was closed in 1490 after his death.[172]

Bratislava is the seat of the largest university (Comenius University,27,771 students),[173]the largest technical university (Slovak University of Technology,18,473 students),[174]and the oldest art schools (theAcademy of Performing Artsand theAcademy of Fine Arts and Design) in Slovakia. Other institutions of tertiary education are the publicUniversity of Economicsand the first private college in Slovakia,City University of Seattle.[175]In total, about 56,000 students attend university in Bratislava.[176]

There are 65 publicprimary schools,nine private primary schools and ten religious primary schools.[177]Overall, they enroll 25,821 pupils.[177]The city's system ofsecondary education(some middle schools and all high schools) consists of 39gymnasiawith 16,048 students,[178]37 specializedhigh schoolswith 10,373 students,[179]and 27vocational schoolswith 8,863 students (data as of 2007[update]).[180][181]

TheSlovak Academy of Sciencesis also based in Bratislava. However, the city is one of the few European capitals to have neither anobservatorynor aplanetarium.The nearest observatory is inModra,30 kilometres (19 mi) away, and the nearest planetarium is inHlohovec,70 kilometres (43 mi) away.

Transport[edit]

The geographical position of Bratislava in Central Europe has long made it a natural crossroads for international trade traffic.[182]

Public transport in Bratislava is managed byDopravný podnik Bratislava,a city-owned company. The transport system is known asMestská hromadná doprava(MHD, Municipal Mass Transit) and employs buses,trams,andtrolleybuses.[183]Most of the Bratislava public transport is coated in a typical color combination of red and black.

Bratislava is also part of an integrated system,IDS BK,connecting city public transport with other transport companies in the Bratislava region. Traveling with a single ticket is possible throughout the system network, both in Bratislava and to the nearby villages and cities, including three other districts of Senec, Malacky, and Pezinok.

As a rail hub, the city has direct connections toAustria,Hungary,theCzech Republic,Poland,Germany,Croatia,Sloveniaand the rest of Slovakia.Bratislava-Petržalka railway stationandBratislava Main stationare the principal railway stations.

Daily trains and buses from Bratislava to Vienna run multiple times every hour, with theWien Hbftrain station serving Bratislava as well, with more connections throughout Europe, opening possibilities for a travel toItalyandFrancewith a quick change of trains in Vienna.

The main bus station (Autobusová stanicaorAutobusová stanica Nivy) is located at Mlynské Nivy, east of the city centre, and offers both bus connections to cities in Slovakia and international bus lines. A new bus station attached to a shopping mall, administration centre, and Bratislava's tallest skyscraper, Nivy Tower, was opened on the 30th of September 2021.[184]The bus station lies underground and its design was inspired by airport terminals. The waiting area offers enough space and comfort to wait for the bus.

The motorway system provides direct access toBrnoin the Czech Republic,Viennain Austria,Budapestin Hungary,Trnava,and other points in Slovakia. TheA6 motorwaybetween Bratislava andViennawas opened in November 2007.[185]

ThePort of Bratislavais one of the two internationalriver portsin Slovakia. The port provides access to theBlack Seavia the Danube and to theNorth Seathrough theRhine–Main–Danube Canal.Additionally, tourist lines operate from Bratislava's passenger port, including routes toDevín,Vienna,and elsewhere. In Bratislava there are currently six bridges standing over theDanube(ordered by the flow of the river):Most Lafranconi(Lafranconi Bridge),Most SNP(Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising, previously calledNový mostorNew bridge) with the famousUFO Tower,Starý most(The Old Bridge),Most Apollo(Apollo Bridge),Prístavný most(The Harbor Bridge) and Lužný most (The Floodplain bridge).

Bratislava'sM. R. Štefánik Airportis the maininternational airportin Slovakia. The airport is located 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) north-east of the city centre, with fast connections served by the city public transport. It serves civil and governmental, scheduled and unscheduled domestic and international flights. The current runways support the landing for all common types of aircraft. It served 2,024,000 passengers in 2007.[186]Bratislava is also served by theVienna International Airportlocated 49 kilometres (30.4 mi) west of the city centre. It is common for Bratislava residents to use the Vienna airport often, as it offers more variety and can be reached under 60 minutes from Bratislava with a car.

International relations[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Bratislava istwinnedwith:

Brno,Czech Republic[187]

Brno,Czech Republic[187] Székesfehérvár,Hungary[187]

Székesfehérvár,Hungary[187] Kraków,Poland[187]

Kraków,Poland[187] Warsaw,Poland[187]

Warsaw,Poland[187] Perugia,Italy(1962)[187]

Perugia,Italy(1962)[187] Ljubljana,Slovenia(1967)[187]

Ljubljana,Slovenia(1967)[187] Yerevan,Armenia(2001)[188]

Yerevan,Armenia(2001)[188] Larnaca,Cyprus(1989)[188]

Larnaca,Cyprus(1989)[188] Turku,Finland(1976)[188]

Turku,Finland(1976)[188] Bremen,Germany(1989)[188]

Bremen,Germany(1989)[188] Alexandria,Egypt[188]

Alexandria,Egypt[188] Kyiv,Ukraine[187]

Kyiv,Ukraine[187] Cleveland,United States[188]

Cleveland,United States[188]

* Numbers in parentheses list the year of twinning. The first agreement was signed with the city ofPerugiain Italy on 18 July 1962.

Notable people[edit]

Honorary citizens[edit]

People who have received thehonorary citizenshipof Bratislava are:

| Date | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 4 September 1990 | Helmut Zilk | Mayor ofVienna |

| 24 September 1997 | Edita Gruberová | Sopranist |

| 19 November 2009 | Václav Havel(1936–2011) | President of Czechoslovakia1989–1992 andPresident of the Czech Republic1993–2003[189] |

| 26 September 2011 | Major GeneralRoy Martin Umbarger | United States ArmyOfficer[190] |

| 28 October 2014 | Karel Gott | Czech singer[191] |

| 19 December 2020 | John Paul II | Catholic Pope[192] |

Image gallery[edit]

-

Main entrance of theBratislava Castle

-

TheOld Town Hall,the oldest city hall in the country

-

Reformed church

-

Church of Saint Stephen

-

The Old Town of Bratislava

-

Streets of the Old Town

-

Bratislava Old Town

-

TheRococo-style "House of the Good Shepherd",home to the Museum of Clocks

-

Laurinská Street

-

Stará Tržnica Market Hall, the oldest indoor market in Bratislava

-

Einsteinova street

-

Danube promenade

-

Embankment

-

Danube river and the Slovak National Uprising Bridge

-

Slovak Radioheadquarters building

-

CityShuttle train connects Bratislava with Austria's capitalVienna.

-

Refinery of Slovnaft in Bratislava

-

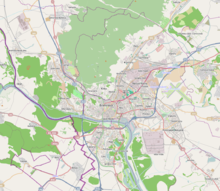

Map of Bratislava in city centre

-

Manhole cover in Bratislava

See also[edit]

- List of municipalities and towns in Slovakia

- List of streets in Bratislava

- List of fountains in Bratislava

Notes[edit]

- ^"Bratislava finds census results as positive".Pravda.sk.RetrievedDecember 31,2021.

- ^"EU regions by GDP, Eurostat".

- ^Wells, John C. (2008),Longman Pronunciation Dictionary(3rd ed.), Longman,ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0

- ^Roach, Peter (2011),Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary(18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-15253-2

- ^"Market Locator's analysis of the real number of Bratislava's inhabitants".Denník SME. May 26, 2017.RetrievedJune 29,2020.

- ^Dominic Swire (2006)."Bratislava Blast".Finance New Europe. Archived fromthe originalon December 10, 2006.RetrievedMay 8,2007.

- ^"Brochure – Culture and Attractions".City of Bratislava. 2006. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on March 7, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.

- ^Gruber, Ruth E. (March 10, 1991)."Charm and Concrete in Bratislava".The New York Times.RetrievedJuly 27,2008.

- ^"Brochure – Welcome to Bratislava".City of Bratislava. 2006. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on March 5, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.

- ^"Regional gross domestic product (PPS per inhabitant) by NUTS 2 regions".ec.europa.eu.Archivedfrom the original on July 13, 2023.RetrievedJuly 27,2023.

- ^"Bratislava je tretí najbohatší región únie. Ako je možné, že predbehla Londýn či Paríž?".Finweb.hnonline.sk. March 2017.RetrievedDecember 15,2017.

- ^"Bratislava – capital city of Slovakia versus other regions of Slovak Republic".Laboureconomics.wordpress. April 29, 2013.RetrievedDecember 15,2017.

- ^"Bratislava reports increase in visitors".The Slovak Spectator.December 6, 2016.RetrievedJanuary 9,2019.

- ^Bugge, Peter (March 27, 2009)."The Making of a Slovak City: The Czechoslovak Renaming of Pressburg/Pozsony/Prešporok, 1918–19".Austrian History Yearbook.35.Cambridge University: 205–227.doi:10.1017/S0067237800020993.S2CID145074158.RetrievedMarch 25,2023.

- ^abcdefPeter Salner (2001)."Ethnic polarisation in an ethnically homogeneous town"(PDF).Czech Sociological Review.9(2): 235–246. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.

- ^Nagayo, Susumu."A Reflection on the Names of a City in the Borderlands - Pressburg/Pozsony/Prešporok/Bratislava"(PDF).Slavic-Eurasian Research Center.Hokkaido University.RetrievedJune 16,2020.

- ^"Bratislava".The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names(3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2014.ISBN9780191751394.

- ^Duin, Pieter C. van (May 1, 2009).Central European Crossroads: Social Democracy and National Revolution in Bratislava (Pressburg), 1867-1921.Berghahn Books.ISBN978-1-84545-918-5.

- ^Grässe, J. G. Th.(1909) [1861].Orbis latinus; oder, Verzeichnis der wichtigsten lateinischen Orts- und Ländernamen(in German) (2nd ed.). Berlin: Schmidt.OCLC1301238.RetrievedFebruary 11,2016– via Columbia University.

- ^"History – Celtic settlements".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", p. 73

- ^"History – Bratislava and the Romans".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Kováč et al.,Kronika Slovenska 1,p. 90

- ^Kováč et al.,Kronika Slovenska 1,p. 95

- ^Kristó, Gyula, ed. (1994).Korai Magyar Történeti Lexikon – 9–14. század(Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History – 9–14th centuries).Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 128, 167.ISBN963-05-6722-9.

- ^"Meine wissenschaftlichen Publikationen (Fortsetzung, 2002–2004)".Uni-bonn.de. October 31, 2006. Archived fromthe originalon May 17, 2008.RetrievedMay 28,2009.

- ^Toma, Peter A. (2001).Slovakia: from Samo to Dzurinda Studies of nationalities.Hoover Institution Press.ISBN978-0-8179-9951-3.

- ^Špiesz, "Bratislava v stredoveku", p. 9

- ^Bowlus, Charles R. (2006).The battle of Lechfeld and its aftermath.p. 83.

- ^"History – Bratislava in the Middle Ages".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Špiesz, "Bratislava v stredoveku", p. 43

- ^Špiesz, "Bratislava v stredoveku", p. 132

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 30

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 62

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", pp. 31–34

- ^"Epidemic diseases and their reminders in the City of Bratislava".krakow.pl.RetrievedAugust 22,2023.

- ^abcWeinberger, Jill Knight (November 19, 2000)."Rediscovering Old Bratislava".The New York Times.RetrievedJuly 27,2008.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", pp. 34–36

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", pp. 35–36

- ^Slowakei, p.68, Renata SakoHoess, DuMont Reiseverlag, 2004.ISBN978-3-7701-6057-0

- ^Sources of Slovac music, Slovenské národné múzeum, Ivan Mačák,Slovak National Museum,1977.

- ^"History – Maria Theresa's City".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", pp. 350–351

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", p. 384

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", p. 385

- ^Erzsébet Varga, "Pozsony", p. 14 (Hungarian)

- ^"History – Between the campaigns of the Napoleonic troops and the abolition of bondage".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", p. 444 - ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", p. 457

- ^"History – Austro-Hungarian Empire".Železničná spoločnosť Cargo Slovakia. n.d. Archived fromthe originalon November 29, 2007.RetrievedMay 28,2008.

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", pp. 426–427

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", p. 451

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 1", p. 430

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 41

- ^"The Czech invasion of 'Wilson City'".Radio Prague International.November 22, 2011.RetrievedAugust 23,2023.

- ^Simon, Attila (2011). "I. Changes of Sovereignty and the New Nation States in the Danube Region 1918–1921 – 3. The Creation of Hungarian Minority Groups – Czechoslovakia: Slovakia". In Bárdi, Nándor; Szarka, Csilla; Szarka, László (eds.).Minority Hungarian Communities in the Twentieth Century (East European Monographs, 774).Translated by McLean, Brian; Suff, Matthew. New York: Columbia University Press, Atlantic Research and Publications, Inc., Institute for Ethnic and National Minority Studies of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.ISBN978-0-88033-677-2.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 42

- ^Hronský, Marián (2001). "2. The Process of Occupation of the Territory of Slovakia by the Czecho-Slovak Army".The Struggle for Slovakia and the Treaty of Trianon.Bratislava: Slovak Academy of Sciences. p. 133.ISBN80-224-0677-5.

- ^Hronský, Marián (2001). "2. The Process of Occupation of the Territory of Slovakia by the Czecho-Slovak Army".The Struggle for Slovakia and the Treaty of Trianon.Bratislava: Slovak Academy of Sciences. p. 149.ISBN80-224-0677-5.

- ^Tibenský, Ján; et al. (1971).Slovensko: Dejiny.Bratislava: Obzor.

- ^"History – First Czechoslovak Republic".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Kačírek, Ľuboš; Tišliar, Pavol (2014b).Petržalka v rokoch 1919 – 1946(in Slovak). Bratislava: Stimul. p. 9.

- ^"History of Hungarians in the first Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1919 section)".2008. Archived fromthe originalon December 27, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 5,2008.

- ^"History of Hungarians in the first Czechoslovak Republic".2008. Archived fromthe originalon January 11, 2009.RetrievedJune 22,2008.

- ^ab"History – Wartime Bratislava".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Kováč et al., "Bratislava 1939–1945", pp. 16–17

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 43. Kováč et al., "Bratislava 1939–1945, pp. 174–177

- ^abcd"History – Post-war Bratislava".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^"Bratislava in World War 2".Bratislava Shooting Club. August 23, 2016.RetrievedJuly 21,2020.

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 2", p. 300

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 2", pp. 307–308

- ^"The changing face of Bratislava".The Slovak Spectator.March 21, 2014.

- ^Kováč et al., "Kronika Slovenska 2" p. 498

- ^"History – Capital city for second time".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Autoatlas – Slovenská republika(Map) (6th ed.). Vojenský kartografický ústav a.s. 2006.ISBN80-8042-378-4.Archived fromthe originalon January 18, 2006.RetrievedJuly 22,2009.

- ^"Vysoké Tatry – Basic characteristics".Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. December 31, 2005. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedAugust 16,2007.

- ^"Basic Information – Position".City of Bratislava. February 14, 2005. Archived fromthe originalon July 31, 2007.RetrievedMay 1,2007.

- ^"plantsdb".plantsdb.gr. Archived fromthe originalon October 13, 2012.RetrievedMarch 7,2015.

- ^ab"Bratislava Weather"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. March 14, 2007. Archived fromthe originalon October 29, 2007.RetrievedNovember 1,2007.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 10

- ^"Prvá augustová vlna horúčav zo štvrtka, 8 August 2013"(in Slovak). Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute. August 9, 2013.RetrievedDecember 1,2013.

- ^Thorpe, Nick (August 16, 2002)."Defences hold fast in Bratislava".BBC.RetrievedApril 27,2007.

- ^Handzo, Juraj (January 24, 2007)."Začne sa budovať protipovodňový systém mesta(Construction starts for city's flood protection) "(in Slovak). Bratislavské Noviny.RetrievedApril 28,2007.

- ^"World Weather Information Service – Bratislava".World Meteorological Organization. Archived fromthe originalon August 7, 2023.RetrievedAugust 7,2023.

- ^"Bratislava Airport Climate Normals 1991–2020".World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020).National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived fromthe originalon August 7, 2023.RetrievedAugust 7,2023.

- ^"Bratislava Ivanka"(in Italian).Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute.Archived fromthe originalon August 30, 2023.RetrievedAugust 30,2023.

- ^Habšudová, Zuzana (April 23, 2007)."City to cut tall buildings down to size".The Slovak Spectator.Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedMarch 13,2006.

- ^"Michael's Gate".Bratislava Culture and Information Centre. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon March 3, 2016.RetrievedJune 10,2007.

- ^"Narrowest house in Europe".Bratislava Culture and Information Centre. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedJune 10,2007.

- ^ab"University Library in Bratislava – The Multifunctional Cultural Centre"(PDF).University Library in Bratislava. 2005. pp. 34–36. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on June 7, 2007.RetrievedJune 14,2007.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 147

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 112

- ^"St. Martin's Cathedral".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon July 31, 2007.RetrievedJune 8,2007.

- ^"Františkánsky kostol a kláštor"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. February 14, 2005. Archived fromthe originalon May 29, 2007.RetrievedJune 10,2007.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 179

- ^"Turistické informácie – Slavín"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedMay 6,2007.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 135

- ^ab"A DAY IN BRATISLAVA: THE BEAUTY ON THE DANUBE".Alwayswanderlust.Archived fromthe originalon December 16, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 30,2017.

- ^abLiptáková, Jana (April 23, 2007)."New Slovak National Theatre opens after 21 years".The Slovak Spectator.Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedAugust 16,2007.

- ^abNahálková, Ela (January 29, 2007)."Bratislava's mayors lay out real estate plans".The Slovak Spectator.Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedAugust 16,2007.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", pp. 11–12

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 121

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 124

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 128

- ^"Devín Castle, Slovakia".danubetourism.eu.danubetourism.eu. October 6, 2023.RetrievedOctober 6,2023.

- ^Beáta Husová (2007)."Bratislava City Museum: Museums: Devín Castle – National Cultural Monument".Bratislava City Museum. Archived fromthe originalon June 23, 2007.RetrievedJune 21,2007.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 191

- ^"Pamiatkové hodnoty Rusoviec – Rusovský kaštieľ(Historical landmarks of Rusovce – Rusovce mansion) "(in Slovak). Rusovce. May 6, 2004. Archived fromthe originalon October 12, 2007.RetrievedJune 1,2007.

- ^"Múzeum Antická Gerulata(Ancient Gerulata Museum) "(in Slovak). Rusovce. May 6, 2004. Archived fromthe originalon October 12, 2007.RetrievedJune 1,2007.

- ^"Natural Environment".City of Bratislava. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon March 5, 2007.RetrievedMay 1,2007.

- ^"Environment: Sad Janka Kráľa (Životné prostredie: Sad Janka Kráľa)"(in Slovak). Borough of Petržalka. January 29, 2007. Archived fromthe originalon September 28, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.

- ^"Bratislava Culture and Information Centre – Botanical gardens".Bratislava Culture and Information Centre. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedJuly 28,2007.

- ^"Rusovce".City of Bratislava. February 14, 2005. Archived fromthe originalon July 16, 2007.RetrievedMay 1,2007.

- ^"Statistical yearbook of the capital of the SR Bratislava 2022".tatistical Office of the SR.RetrievedMarch 1,2023.

- ^"Bratislava Population".

- ^"Slovakia: Regions and Major Cities".

- ^Iris Engemann (March 7, 2008)."The Slovakization of Bratislava 1918–1948. Processes of national appropriation in the interwar-period"(PDF).Frankfurt:European University Viadrina.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on March 3, 2016.RetrievedDecember 30,2008.

- ^"Name Changes of the Street in Bratislava From Political Reasons After the Creation of the First Czechoslovak Republic, The disintegration of the Austria–Hungarian Monarchy (In Hungarian)"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on October 27, 2007.

- ^Lacika, "Bratislava", p. 43

- ^The Story of the Jewish Community in Bratislava- an online exhibition atYad Vashemwebsite

- ^"Germans and Hungarians in Pozsony"(PDF).Epa.oszk.hu.2008.RetrievedJune 22,2008.

- ^"A Beneš-dekrétum és a reszlovakizáció hatása".Shp.hu.RetrievedDecember 15,2017.

- ^"Samospráva"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon October 11, 2007.RetrievedNovember 21,2007.

- ^"Historický vývoj samosprávy"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedJune 6,2007.

- ^"Primátor"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon June 2, 2007.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^ab"Mestská rada"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^"Mestské zastupiteľstvo"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^ab"Komisie mestského zastupiteľstva"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon December 24, 2012.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^"Magistrát"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon May 26, 2012.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^"Bratislava – Local Government System".theparliament. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon November 12, 2006.RetrievedApril 30,2007.

- ^ab"Petržalka City".City of Bratislava. March 1, 2007. Archived fromthe originalon October 12, 2007.RetrievedJanuary 29,2008.

Petržalka City will transform the largest and most densely populated housing estate in Central Europe from a monotone cement-panel housing scheme into a fully-fledged town with autonomous multipurpose centre.

- ^"Local Government".City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon March 5, 2007.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^"2015 GDP per capita in 276 EU regions: Four regions over double the EU average… and still nineteen regions below half of the average"(PDF).Ec.europa.eu.RetrievedDecember 15,2017.

- ^a.s, Petit Press (March 2, 2016)."Bratislava is the sixth richest region of EU, but…".spectator.sme.sk.RetrievedOctober 31,2022.

- ^"Nezamestnanosť - Bratislavský kraj"(in Slovak). Dlznik.sk. June 2023.RetrievedAugust 7,2023.

- ^"Platy, benefity, top pozície - Bratislavský kraj - Platy.sk".Platy.sk.RetrievedMay 19,2024.

- ^"Economy and employment".City of Bratislava. February 23, 2006. Archived fromthe originalon July 1, 2007.RetrievedJune 8,2007.

- ^"Basic Information".City of Bratislava. 2007.RetrievedMay 3,2007.

- ^"TREND Top 200".Trend(in Slovak). 2018. Archived fromthe originalon April 4, 2019.RetrievedApril 4,2019.

- ^Jeffrey Jones (August 27, 1997)."VW Bratislava expands production".The Slovak Spectator.Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.

- ^"A brief journey through a long history: 2000–2003".Volkswagen. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon April 21, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.."Volkswagen (Slovak Republic)".Global Auto Systems Europe. 2006. Archived fromthe originalon April 16, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.."Volkswagen sales up to a record Sk195.5 billion".The Slovak Spectator.April 2, 2007. Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.

- ^"Lenovo invests in Slovakia with new jobs".Slovak Investment and Trade Development Agency.April 20, 2006.RetrievedApril 25,2007.."Dell in Bratislava".Dell. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedApril 25,2007.

- ^Baláž, Vladimír (2007). "Regional Polarization under Transition: The Case of Slovakia".European Planning Studies.15(5): 587–602.doi:10.1080/09654310600852639.S2CID154927365.

- ^"Slovenské online kasína s oficiálnou licenciou a bonusmi".slovenskekasina.sk.RetrievedMarch 8,2022.

- ^"River Park".City of Bratislava. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedJune 6,2007.

- ^"EUROVEA International Trade Centre".City of Bratislava. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon July 18, 2007.RetrievedJune 6,2007.

- ^"Regeneration of Central Railway Station Square Area".City of Bratislava. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedJune 3,2007.

- ^Tom Nicholson (January 29, 2007)."Twin City to upgrade bus station".The Slovak Spectator.Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedJune 6,2007.

- ^"Budget".City of Bratislava. 2010. Archived fromthe originalon July 3, 2009.RetrievedDecember 30,2010.

- ^"Obchodné spoločnosti mesta"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 15, 2012.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^"Mestské organizácie"(in Slovak). City of Bratislava. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon January 18, 2012.RetrievedApril 29,2007.

- ^ab"Tourism statistics in Bratislava - for the year 2022"(PDF).Visit Bratislava.Bratislava Tourist Board.Archived(PDF)from the original on September 2, 2023.RetrievedFebruary 9,2023.

- ^Zuzana Habšudová (May 29, 2006)."Bratislava wearies of stag tourism".The Slovak Spectator.Archived fromthe originalon September 5, 2006.RetrievedApril 28,2007.

We hope the number of British tourists visiting Slovakia will continue to increase, but we want it to be responsible tourism.

- ^Pressburg_Yeshiva_(Austria-Hungary)

- ^"Cultural Institutions".Bratislava Culture and Information Centre. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon July 3, 2012.RetrievedJuly 26,2007.

- ^abcBratislavaCity.Sk (2011)."Slovak National Theatre".bratislava-city.sk.Archived fromthe originalon September 29, 2011.RetrievedJuly 2,2011.

- ^"Classical Bratislava | What to do?".

- ^"Visit Bratislava – Culture".City of Bratislava. Archived fromthe originalon March 5, 2007.RetrievedMay 1,2007.

- ^"Musical Bratislava".Welcome to Bratislava. May 18, 2021.

- ^"sluk.sk | Slovenský ľudový umelecký kolektív".sluk.sk.Archived fromthe originalon September 22, 2022.RetrievedMay 19,2020.

- ^"Lúčnicu čaká obrovská zmena. Po rokoch sa tanečníkom splnil vytúžený sen".Glob.sk(in Slovak). April 24, 2020.RetrievedMay 19,2020.

- ^Burda, Michal (May 14, 2020)."Vystoupení SĽUKu ve Vsetíně se ruší, zasáhlo slovenské ministerstvo".Valašský deník(in Czech).RetrievedMay 19,2020.

- ^"Slovak national museum – SNM office".Slovak National Museum. 2007.RetrievedOctober 7,2007.

- ^Beáta Husová (January 19, 2007)."Profile of the museum".Bratislava City Museum. Archived fromthe originalon September 20, 2007.RetrievedMay 4,2007.

- ^"Bratislava City Gallery – about us – buildings".Bratislava City Gallery. 2007.RetrievedMay 17,2007.

- ^"Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum – About us".Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon December 8, 2007.RetrievedJune 21,2007.

- ^"Slovan Bratislava – najväčšie úspechy (Slovan Bratislava – greatest achievements)"(in Slovak). Slovan Bratislava. 2006. Archived fromthe originalon January 8, 2008.RetrievedMay 15,2007.."Slovan Bratislava – História (History)"(in Slovak). Slovan Bratislava. 2006. Archived fromthe originalon October 24, 2007.RetrievedMay 15,2007.

- ^Marta Ďurianová (May 22, 2006)."Slovakia to host ice hockey World Championships in 2011".The Slovak Spectator.Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedApril 27,2007.

- ^Jewish Sports Legends: The International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.U of Nebraska Press. August 2020.ISBN9781496201881.

- ^Litsky, Frank (June 10, 2004)."Ladislav Hecht, 94, a Tactician On the Tennis Courts in the 30's".The New York Times.

- ^"Twin City Journal – The Oldest Athletic Event in Slovakia"(PDF).City of Bratislava. April 2006. p. 7. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on June 14, 2007.RetrievedApril 28,2007.

- ^"They call him Efa or Jozef Toth left the flat track at the top".Speedway A - Z.February 9, 2018.RetrievedMarch 29,2024.

- ^"Academia Istropolitana".City of Bratislava. February 14, 2005. Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedJanuary 5,2008.

- ^"Univerzita Komenského"(PDF)(in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.Retrieved2008-02-15.

- ^"Slovenská technická univerzita"(PDF)(in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.Retrieved2008-02-15.

- ^"Bratislava, Slovakia: Vysoka Skola Manazmentu (VSM)".City University of Seattle. 2005. Archived fromthe originalon February 12, 2008.RetrievedJune 1,2007.

- ^"Visit Bratislava – Facts and Figures".City of Bratislava. 2007. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on March 5, 2007.RetrievedApril 30,2007.

- ^ab"Prehľad základných škôl v školskom roku 2006/2007"(PDF)(in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. 2006. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.Retrieved2008-02-15.

- ^"Prehľad gymnázií v školskom roku 2006/2007"(PDF)(in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.Retrieved2008-02-15.

- ^"Prehľad stredných odborných škôl v školskom roku 2006/2007"(PDF)(in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.Retrieved2008-02-15.

- ^"Prehľad združených stredných škôl v školskom roku 2006/2007"(PDF)(in Slovak). Ústav informácií a prognóz školstva. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.Retrieved2008-02-14.