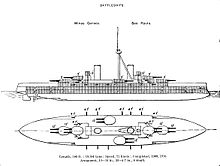

Brazilian battleshipSão Paulo

São Pauloon itssea trials,1910

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | São Paulo |

| Namesake | The state and city ofSão Paulo[1] |

| Builder | Vickers,Barrow-in-Furness,United Kingdom[2] |

| Laid down | 30 April 1907[1][2] |

| Launched | 19 April 1909[1][2] |

| Commissioned | 12 July 1910[1][2] |

| Stricken | 2 August 1947[1][3] |

| Motto | Non Ducor, Duco[1][A] |

| Fate | Sank 1951 while en route to be scrapped |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Minas Geraes-classbattleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 83 ft (25 m)[5] |

| Draft | |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph)[6] |

| Endurance | 10,000 nautical miles @ 10 knots (11,500 mi @ 11.5 mph or 18,500 km @ 18.5 km/h)[2] |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

| Notes | Characteristics are as built;cf.Specifications of theMinas Geraes-class battleships |

São Paulowas adreadnoughtbattleshipof theBrazilian Navy.It was the second of two ships in theMinas Geraesclass,and was named after thestateandcityof São Paulo.

The British companyVickersconstructedSão Paulo,launchingit on 19 April 1909. The ship wascommissionedinto the Brazilian Navy on 12 July 1910. Soon after, it was involved in theRevolt of the Lash(Revolta de Chibata), in which crews on four Brazilian warships mutinied over poor pay and harsh punishments for even minor offenses. After entering the First World War, Brazil offered to sendSão Pauloand itssisterMinas Geraesto Britain for service with theGrand Fleet,but Britain declined since both vessels were in poor condition and lacked the latest fire control technology. In June 1918, Brazil sentSão Pauloto the United States for a full refit that was not completed until 7 January 1920, well after the war had ended. On 6 July 1922,São Paulofired its guns in angerfor the first time when it attacked a fort that had been taken during theCopacabana Fort revolt.Two years later, mutineers took control of the ship and sailed it toMontevideoinUruguay,where they obtainedasylum.

In the 1930s,São Paulowas passed over for modernization due to its poor condition—it could only reach a top speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), less than half its design speed. For the rest of its career, the ship was reduced to a reserve coastal defense role. When Brazil entered the Second World War,São Paulosailed toRecifeand remained there as the port's main defense for the duration of the war.Strickenin 1947, the dreadnought remained as atraining vesseluntil 1951, when it was taken under tow to be scrapped in the United Kingdom. The tow lines broke during a strong gale on 6 November, when the ships were 150 nmi (280 km; 170 mi) north of theAzores,andSão Paulowas lost.

Background

[edit]Beginning in the late 1880s, Brazil's navy fell into obsolescence, a situation exacerbated by an1889 coup d'état,which deposed EmperorDomPedro II,and an1893 civil war.[7][8][9][C]Despite having nearly three times the population of Argentina and almost five times the population of Chile,[8][11]by the end of the 19th century Brazil was lagging behind the Chilean and Argentine navies in quality and total tonnage.[8][9][D]

At the turn of the 20th century, soaring demand forcoffeeandrubberbrought prosperity to the Brazilian economy.[11]The government of Brazil used some of the extra money from this economic growth to finance a naval building program in 1904,[2]which authorized the construction of a large number of warships, including three battleships.[12][13]The minister of the navy, AdmiralJúlio César de Noronha,signed a contract withArmstrong Whitworthfor three battleships on 23 July 1906.[14]The newdreadnoughtbattleship design, which debuted in December 1906 with the completion ofthe namesake ship,rendered the Brazilian ships, and all other existing capital ships, obsolete.[15]

The money authorized for naval expansion was redirected by the new Minister of the Navy, Rear AdmiralAlexandrino Fario de Alencar,to building two dreadnoughts, with plans for a third dreadnought after the first was completed, two scout cruisers (which became theBahiaclass), ten destroyers (theParáclass), and three submarines.[16][17]The three battleships on which construction had just begun were scrapped beginning on 7 January 1907, and the design of the new dreadnoughts was approved by the Brazilians on 20 February 1907.[15]In South America, the ships came as a shock and kindled anaval arms race among Brazil, Argentina, and Chile.The1902 treatybetween the latter two was canceled upon the Brazilian dreadnought order so both could be free to build their own dreadnoughts.[8]

Minas Geraes,thelead ship,was laid down by Armstrong on 17 April 1907, whileSão Paulofollowed thirteen days later at Vickers.[2][5][18]The news shocked Brazil's neighbors, especially Argentina, whoseMinister of Foreign Affairsremarked that eitherMinas GeraesorSão Paulocould destroy the entire Argentine and Chilean fleets.[19]In addition, Brazil's order meant that they had laid down a dreadnought before many of the other major maritime powers, such as Germany, France or Russia,[E]and the two ships made Brazil the third country to have dreadnoughts under construction, behind the United Kingdom and the United States.[11][21]

Newspapers and journals around the world, particularly in Britain and Germany, speculated that Brazil was acting as a proxy for a naval power which would take possession of the two dreadnoughts soon after completion, as they did not believe that a previously insignificant geopolitical power would contract for such powerful warships.[2][22]Despite this, the United States actively attempted to court Brazil as an ally; caught up in the spirit, U.S. naval journals began using terms like "Pan Americanism" and "Hemispheric Cooperation".[2]

Early career

[edit]São Paulowaschristenedby Régis de Oliveira, the wife of Brazil's minister to Great Britain, andlaunchedat Barrow-in-Furness on 19 April 1909 with many South American diplomats and naval officers in attendance.[23]The ship wascommissionedon 12 July,[1][24]and afterfitting-outandsea trials,[24]it leftGreenockon 16 September 1910.[25]Shortly thereafter, it stopped inCherbourg,France, to embark theBrazilian PresidentHermes Rodrigues da Fonseca.[26]Departing on the 27th,[27]São Paulosailed toLisbon,Portugal, where Fonseca was a guest of Portugal's KingManuel II.Soon after they arrived the5 October 1910 revolutionbegan, which caused the fall of the Portuguese monarchy.[28]Although the president offered political asylum to the king and his family, the offer was refused.[29]A rumor that the king was on board, circulated by newspapers and reported to the Brazilian legation in Paris,[30][31]led revolutionaries to attempt to search the ship, but they were denied permission. They also asked for Brazil to land marines "to help in the maintenance of order", but this request was also denied.[32]São Pauloleft Lisbon on 7 October for Rio de Janeiro,[28][33]and docked there on 25 October.[25]

Revolt of the Lash

[edit]

Soon afterSão Paulo's arrival, a major rebellion known as the Revolt of the Lash, orRevolta da Chibata,broke out on four of the newest ships in the Brazilian Navy. The initial spark was provided on 16 November 1910 whenAfro-BraziliansailorMarcelino Rodrigues Menezeswas brutally flogged 250 times for insubordination.[F]Many Afro-Brazilian sailors were sons of former slaves, or were former slaves freed under theLei Áurea(abolition) but forced to enter the navy. They had been planning a revolt for some time, and Menezes became the catalyst. Further preparations were needed, so the rebellion was delayed until 22 November. The crewmen ofMinas Geraes,São Paulo,the twelve-year-oldDeodoro,and the newBahiaquickly took their vessels with only a minimum of bloodshed: two officers onMinas Geraesand one each onSão PauloandBahiawere killed.[35]

The ships were well-supplied with foodstuffs, ammunition, and coal, and the only demand of mutineers—led byJoão Cândido Felisberto—was the abolition of "slavery as practiced by the Brazilian Navy". They objected to low pay, long hours, inadequate training, and punishments includingbolo(being struck on the hand with aferrule) and the use of whips or lashes (chibata), which eventually became a symbol of the revolt. By the 23rd, the National Congress had begun discussing the possibility of a generalamnestyfor the sailors. SenatorRuy Barbosa,long an opponent of slavery, lent a large amount of support, and the measure unanimously passed theFederal Senateon 24 November. The measure was then sent to theChamber of Deputies.[36]

Humiliated by the revolt, naval officers and the president of Brazil were staunchly opposed to amnesty, so they quickly began planning to assault the rebel ships. The officers believed such an action was necessary to restore the service's honor. The rebels, believing an attack was imminent, sailed their ships out ofGuanabara Bayand spent the night of 23–24 November at sea, only returning during daylight. Late on the 24th, the President ordered the naval officers to attack the mutineers. Officers crewed some smaller warships and the cruiserRio Grande do Sul,Bahia's sister ship with ten 4.7-inch guns. They planned to attack on the morning of the 25th, when the government expected the mutineers would return to Guanabara Bay. When they did not return and the amnesty measure neared passage in the Chamber of Deputies, the order was rescinded. After the bill passed 125–23 and the president signed it into law, the mutineers stood down on the 26th.[37]

During the revolt, the ships were noted by many observers to be well handled, despite a previous belief that the Brazilian Navy was incapable of effectively operating the ships even before being split by a rebellion. João Cândido Felisberto ordered all liquor thrown overboard, and discipline on the ships was recognized as exemplary. The 4.7-inch guns were often used for shots over the city, but the 12-inch guns were not, which led to a suspicion among the naval officers that the rebels were incapable of using the weapons. Later research and interviews indicate thatMinas Geraes'guns were fully operational, and whileSão Paulo's could not be turned after salt water contaminated thehydraulicsystem, British engineers still on board the ship after the voyage from the United Kingdom were working on the problem. Still, historians have never ascertained how well the mutineers could handle the ships.[38]

First World War

[edit]The Brazilian government declared that the country would be neutral in theFirst World Waron 4 August 1914. The sinking of Brazilian merchant ships by GermanU-boatsled them to revoke their neutrality, then declare war on 26 October 1917.[39]By this time,São Paulowas no longer one of the world's most powerful battleships. Despite an identified need for more modern fire control,[1]it had not been fitted with any of the advances in that technology that had appeared since its construction, and it was in poor condition.[40]For these reasons theRoyal Navydeclined a Brazilian offer to send it andMinas Geraesto serve with theGrand Fleet.[2]In an attempt to bring the battleship up to international standards, Brazil sentSão Pauloto the United States in June 1918 to receive a full refit. Soon after it departed the naval base in Rio de Janeiro, fourteen of the eighteenboilerspowering the dreadnought broke down.[25]The American battleshipNebraska,which was in the area after transporting the body of the late Uruguayan Minister to the United States to Montevideo,[41]rendered assistance in the form of temporary repairs after the ships put in atBahia.Escorted byNebraskaand another American ship,Raleigh,São Paulomade it to theNew York Naval Yardafter a 42-day journey.[2][25]

Major refit and the 1920s

[edit]

São Paulounderwent a refit in New York, beginning on 7 August 1918 and completing on 7 January 1920.[42]Many of its crewmen were assigned to American warships during this time for training.[43]It receivedSperryfire control equipment andBausch and Lombrange-finders for the twosuperfiringturretsforeandaft.A vertical armorbulkheadwas fitted inside all six main turrets, and the secondary battery of 4.7 in (120 mm)casemateguns was reduced from twenty-two to twelve guns. A few modernAAguns were fitted as well: two3 "/50 caliber gunsfromBethlehem Steelwere added on the aft superstructure, 37 mm guns were added near each turret, and3 pounderswere removed from the top of turrets.[42]

After the refit was completed,São Paulopicked up ammunition inGravesendand sailed to Cuba for firing trials.[43]Seven members of the United States'Bureau of Standardstraveled with the ship from New York and observed the operations, which were conducted in theGulf of Guacanayabo.After dropping the Americans off inGuantánamo Bay,[44][45]São Pauloreturned home in early 1920.[25]August 1920 saw the dreadnought sailing to Belgium, where KingAlbert Iand QueenElisabethwere embarked on 1 September to bring them to Brazil.[1][46]After bringing the royals home,São Paulotraveled to Portugal to bring the remains of the former emperor Pedro II and his wife,Teresa Cristina,back to Brazil.[1][47][G]

In 1922,São PauloandMinas Geraeshelped to put down the first of theTenente revolts.Soldiersseized Fort CopacabanainRio de Janeiroon 5 July, but no other men joined them. As a result, some men deserted the rebels, and by the next morning only 200 people remained in the fort.[48]São Paulobombarded the fort, firing five salvos and obtained at least two hits; the fort surrendered half an hour later.[49]The Brazilian Navy's official history reports that one of the hits opened a hole ten meters deep.[24]

Crewmen aboardSão Paulorebelled on 4 November 1924, when FirstLieutenantHercolino Cascardo,sevensecond lieutenantsand 260 others commandeered the ship.[50][51]After the boilers were fired,São Paulo's mutineers attempted to entice the crews ofMinas Geraesand the other ships nearby to join.[3]They were only able to sway the crew of one oldtorpedo boatto the cause.[3]The battleship's crew, angry thatMinas Geraeswould not join them, fired a six-pounder atMinas Geraesthat wounded a cook.[3][29]The mutineers then sailed out of Rio de Janeiro's harbor, where the forts atSanta CruzandCopacabanaengaged her, damagingSão Paulo's fire control system and funnel. The forts stopped firing soon after the battleship returned fire due to concern over possible civilian casualties.[24]The crewmen aboardSão Pauloattempted to join revolutionaries inRio Grande do Sul,but when they found that the rebel forces had moved inland, they set course for Montevideo, Uruguay.[24][29]They arrived on 10 November, where the rebellious members of the crew disembarked and were granted asylum,[3][24]andMinas Geraes,which had been pursuingSão Paulo,escorted the wayward ship home to Rio de Janeiro, arriving on the 21st.[29]

Late career

[edit]

In the 1930s, Brazil decided to modernize bothSão PauloandMinas Geraes.São Paulo's dilapidated state made this uneconomic; at the time it could sail at a maximum of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), less than half its design speed.[42]As a result, whileMinas Geraeswas thoroughly refitted from 1931 to 1938 in theRio de Janeiro Naval Yard,[29]São Paulowas employed as a coast-defense ship, a role in which it remained for the rest of its service life.[3]During the 1932Constitutionalist Revolution,it acted as theflagshipof a navalblockadeof Santos.[29]After repairs in 1934 and 1935, the ship returned to lead three naval training exercises. In the same year, accompanied by the Brazilian cruisersBahiaandRio Grande do Sul,the Argentine battleshipsRivadaviaandMoreno,six Argentine cruisers, and a group of destroyers,São Paulocarried the Brazilian PresidentGetúlio Vargasup theRiver PlatetoBuenos Airesto meet with the presidents of Argentina and Uruguay.[1][52]

In 1936, the crew ofSão Paulo,as well asRio Grande do Sul's crew, played in the Liga Carioca de Football's Open Tournament, a cup where many amateur teams had the chance to play the likes ofFlamengoandFluminense.[53]

As in the First World War, Brazil stayed neutral during the opening years of theSecond World War,until U-boat attacks drove the country to declare war on Germany and Italy on 21 August 1942.[54]The age and condition ofSão Paulorelegated it to the role of harbor defense ship; it set sail for Recife on 23 November 1942 escorted by American destroyersBadgerandDavis,and served as the main defense of the port for the war, only returning to Rio de Janeiro in 1945.[1][3][24][29]Stricken from the naval register on 2 August 1947,[3]the ship remained as atraining vesseluntil August 1951,[29]when it was sold to theIron and Steel Corporation of Great Britainforbreaking up[3]at a cost of 18,810,000 cruzeiros.[55]

Sinking

[edit]

After preparing from 5 to 18 September 1951,São Paulowas given an eight-man caretaker crew and taken under tow by two tugs,DexterousandBustler,departing Rio de Janeiro on 20 September 1951 for a final voyage to the scrappers.[3][56]When north of theAzoresin early November, the flotilla ran into heavy storm seas.[3][29]N

At 17:30 UTC on 4 or 6 November,[H]the sea state causedSão Pauloto pull sharply to starboard and fall into thetroughbetween high waves. The action dragged the tugs astern and toward each other. To avoid a collision,Dexteroussevered its cable and steered away, as had been previously agreed; however, the battleship's weight fell so heavily and abruptly ontoBustler's towing winch that it could not take in the slack—the tow cable became fouled in the tug's propeller and parted.[3][29]The now driftingSão Paulo's port (red) navigation light was visible for several minutes before it disappeared.[59]AmericanB-17 Flying Fortressbombers and British planes were launched to scout the Atlantic for the missing ship;[57][60]it was reported, incorrectly, as found on 15 November.[61]The search was ended on 10 December without findingSão Pauloor its crew.[58]

On 14 October 1954, theBoard of Tradein London released its report on the circumstances and causes for the loss of the ship. The Board concluded that once both tow cables had parted, theSão Paulowould have foundered or capsized within the hour, very near its last sighted position. The Board determined that theSão Paulosank at about 17:45 on 4 November 1951, at position30°49′N23°30′W/ 30.817°N 23.500°W.[59]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^The English translation of this Latin phrase is "I am not led, I lead".São Pauloshared this motto with the city the ship was named after.[1]

- ^Topliss includes specific displacement figures forSão Paulowhich differ fromMinas Geraes.

- ^The civil war began in the southern state ofRio Grande do Sul.Later in 1893, Rear AdmiralCustódio José de Mello,the minister of the navy, revolted against PresidentFloriano Peixoto,bringing nearly all of the Brazilian warships currently in the country with him. Mello's forces tookDesterrowhen the governor surrendered, and began to coordinate with the revolutionaries in Rio Grande do Sul, but loyal Brazilian forces eventually overwhelmed them both. Most of the rebel naval forces were sailed to Argentina, where their crews surrendered; the flagship,Aquidabã,held out near Desterro until sunk by a torpedo boat.[10]

- ^Chile's naval tonnage was 36,896 long tons (37,488 t), Argentina's 34,425 long tons (34,977 t), and Brazil's 27,661 long tons (28,105 t).[8]For an account of the Argentinian–Chilean naval arms races, see Scheina,Naval History,45–52.

- ^Although Germany laid downNassautwo months afterMinas Geraes,Nassauwas commissioned first.[2][20]

- ^The sailor's back was later described byJosé Carlos de Carvalho,a retired navycaptainassigned to be the Brazilian government's representative to the mutineers, as "a mullet sliced open for salting."[34]

- ^cf.Legacy of Pedro II of Brazil.

- ^Whitley and the Brazilian histories give 6 November,[3][29]but contemporary newspaper accounts of the sinking and theBoard of Tradereport use 4 November.[57][58][59]

Endnotes

[edit]- ^abcdefghijklm"E São Paulo,"Navios De Guerra Brasileiros.

- ^abcdefghijklmScheina, "Brazil," 404.

- ^abcdefghijklmWhitley,Battleships,29.

- ^abcdefghiTopliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 250.

- ^abcdefghiTopliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 249.

- ^abcTopliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 251.

- ^Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 240.

- ^abcdeLivermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 32.

- ^abMartins, "Colossos do mares," 75.

- ^Scheina,Naval History,67–76, 352.

- ^abcScheina, "Brazil," 403.

- ^Scheina,Naval History,80.

- ^English,Armed Forces,108.

- ^Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 240–245.

- ^abTopliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 246.

- ^Scheina,Naval History,81.

- ^Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers,"Brazil," 883.

- ^Scheina,Naval History,321.

- ^Martins, "Colossos do mares," 76.

- ^Campbell, "Germany," 145.

- ^Whitley,Battleships,13.

- ^Martins, "Colossos do mares," 77.

- ^"Launch Brazil's Battleship,"The New York Times,20 April 1909, 5.

- ^abcdefg"São Paulo I," Serviço de Documentação da Marinha — Histórico de Navios.

- ^abcdeWhitley,Battleships,28.

- ^"French Criticise Brazil,"The New York Times,25 September 1910, C4.

- ^"Marshal Hermes Da Fonseca,"The Times,28 September 1910, 4e.

- ^ab"Keeping Good Order in New Republic,"The New York Times,8 October 1910, 1–2.

- ^abcdefghijkRibeiro, "Os Dreadnoughts."

- ^"King Manuel Takes Flight Aboard Brazilian Warship,"The Age,7 October 1910, 7.

- ^"Europe Stirred By Lisbon News,"The Telegraph-Herald,5 October 1910, 1.

- ^"The Journey from Lisbon,"The Times,8 October 1910, 5–6a.

- ^"Movements of Warships,"The Times,8 October 1910, 6a.

- ^Quoted in Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 41.

- ^Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 32–38, 50.

- ^Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 40–42.

- ^Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 44–46.

- ^Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 39–40, 48–49, 52.

- ^Scheina,Latin America's Wars,35–36.

- ^Scheina,Latin America's Wars,37.

- ^"Nebraska,"Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships,Naval History & Heritage Command,last modified 7 July 2010.

- ^abcWhitley,Battleships,27.

- ^abLind, "Professional Notes," 452.

- ^Scheina,Latin America,134.

- ^Department of Commerce,Reports,365–66.

- ^"King Albert and His Queen Sail for Brazil Today,"The New York Times,1 September 1920, 1.

- ^Whitley,Battleships,28–29.

- ^Scheina,Latin America's Wars,128.

- ^Poggio, "Um encouraçado contra o forte: 2ª Parte."

- ^Scheina,Latin America's Wars,129.

- ^"Preparing to Take Battleship Home,"The Gazette,12 November 1924, 11.

- ^"Argentina: Lobsters, Pigeons, Parades,"Time,3 June 1935.(subscription required)

- ^TORNEIO ABERTO CARIOCA – 1936(in Portuguese)

- ^Scheina,Latin America's Wars,163–164.

- ^"Brazilian News and Notes,"Brazilian Bulletin8, no. 185 (1 September 1951): 6.

- ^"Battleship lost during tow, Inquiry after three years,"The Times,5 October 1954.

- ^ab"Planes Fail to Find Warship Lost at Sea,"Chicago Daily Tribune,11 November 1951, 27.

- ^ab"Lost Warship Hunt Given Up,"Los Angeles Times,11 December 1951, 13.

- ^abcHayward, R.F.; Atkinson, A.M.; Nutton, W.J. (14 October 1954)."Wreck Report for 'Sao Paulo', 1951"(PDF).Southampton City Council.Archived(PDF)from the original on 24 March 2023.Retrieved24 March2023.

- ^"Towed Warship Missing,"The New York Times,9 November 1951, 49.

- ^"Missing Battleship Located,"The New York Times,16 November 1951, 51.

References

[edit]- "Brazil."Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers20, no. 3 (1909): 833–836.ISSN0099-7056.OCLC3227025.

- Campbell, N.J.M. "Germany." In Gardiner and Gray,Conway's,134–189.

- "E São Paulo."Navios De Guerra Brasileiros.Last modified 24 February 2008.

- English, Adrian J.Armed Forces of Latin America.London: Jane's Publishing Inc., 1984.ISBN0-7106-0321-5.OCLC11537114.

- Gardiner, Robert and Randal Gray, eds.Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921.Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985.ISBN0-87021-907-3.OCLC12119866.

- Lind, Wallace L. "Professional Notes."Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute46, no. 3 (1920): 437–486.

- Livermore, Seward W. "Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925."The Journal of Modern History16, no. 1 (1944): 31–44.JSTOR1870986.ISSN0022-2801.OCLC62219150.

- Martins, João Roberto, Filho. "Colossos do mares[Colossuses of the Seas]. "Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional3, no. 27 (2007): 74–77.ISSN1808-4001.OCLC61697383.

- Morgan, Zachary R. "The Revolt of the Lash, 1910." InNaval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective,edited by Christopher M. Bell and Bruce A. Elleman, 32–53. Portland: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003.ISBN0-7146-8468-6.OCLC464313205.

- Poggio, Guilherme. "Um encouraçado contra o forte: 2ª Parte[A Battleship against the Strong: Part 2]. "n.d. Poder Naval Online. Last modified 12 April 2009.

- Ribeiro, Paulo de Oliveira. "Os Dreadnoughts da Marinha do Brasil: Minas Geraes e São Paulo[The Dreadnoughts of the Brazilian Navy]. "Poder Naval Online. Last modified 8 June 2008.

- "São Paulo I."Serviço de Documentação da Marinha – Histórico de Navios.Diretoria do Patrimônio Histórico e Documentação da Marinha, Departamento de História Marítima. Accessed 27 January 2015.

- Scheina, Robert L. "Brazil." In Gardiner and Gray,Conway's,403–407.

- ———.Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987.Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987.ISBN0-87021-295-8.OCLC15696006.

- ———.Latin America's Wars.Washington, D.C.: Brassey's, 2003.ISBN1-57488-452-2.OCLC49942250.

- Topliss, David. "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 1904–1914."Warship International25, no. 3 (1988): 240–289.ISSN0043-0374.OCLC1647131.

- United States Department of Commerce.Reports of the Department of Commerce.Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1921.OCLC1777213.

- Villiers, Alan.Posted Missing: The Story of Ships Lost Without a Trace in Recent Years.New York,Charles Scribner's Sons,1956. Ch. 5: The Battleship Sao Paulo, p. 79-100.

- Whitley, M.J.Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia.Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998.ISBN1-55750-184-X.OCLC40834665.

Further reading

[edit]- Topliss, David (1988). "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 1904–1914".Warship International.XXV(3): 240–289.ISSN0043-0374.

External links

[edit]- Slideshow of the battleshiponYouTube

- The Brazilian Battleships(Extensive engineering/technical details)