Butterfly

| Butterflies Temporal range:Cretaceous–present,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Papilio machaon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Suborder: | Rhopalocera |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Butterfliesarewinged insectsfrom thelepidopteransuborderRhopalocera,characterized by large, often brightly coloured wings that often fold together when at rest, and a conspicuous, fluttering flight. The group comprises thesuperfamiliesHedyloidea(moth-butterflies in the Americas) andPapilionoidea(all others). The oldest butterfly fossils have been dated to thePaleocene,about 56 million years ago, though they likely originated in the LateCretaceous,about 101 million years ago.[1]

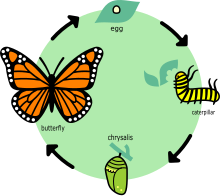

Butterflies have a four-stagelife cycle,and like otherholometabolousinsects they undergocomplete metamorphosis.Winged adults lay eggs on the food plant on which theirlarvae,known ascaterpillars,will feed. The caterpillars grow, sometimes very rapidly, and when fully developed,pupatein achrysalis.Whenmetamorphosisis complete, the pupal skin splits, the adult insect climbs out, expands its wings to dry, and flies off.

Some butterflies, especially in the tropics, have several generations in a year, while others have a single generation, and a few in cold locations may take several years to pass through their entire life cycle.[2]

Butterflies are oftenpolymorphic,and many species make use ofcamouflage,mimicry,andaposematismto evade their predators.[3]Some, like themonarchand thepainted lady,migrateover long distances. Many butterflies are attacked byparasitesorparasitoids,includingwasps,protozoans,flies,and other invertebrates, or arepreyed uponby other organisms. Some species are pests because in their larval stages they can damage domestic crops or trees; other species are agents ofpollinationof some plants. Larvae of a few butterflies (e.g.,harvesters) eat harmful insects, and a few are predators ofants,while others live asmutualistsin association with ants. Culturally, butterflies are a popular motif in the visual and literary arts. TheSmithsonian Institutionsays "butterflies are certainly one of the most appealing creatures in nature".[4]

Etymology

TheOxford English Dictionaryderives the word straightforwardly fromOld Englishbutorflēoge,butter-fly; similar names inOld DutchandOld High Germanshow that the name is ancient, but modern Dutch and German use different words (vlinderandSchmetterling) and the common name often varies substantially between otherwise closely related languages. A possible source of the name is the bright yellow male of the brimstone (Gonepteryx rhamni); another is that butterflies were on the wing in meadows during the spring and summer butter season while the grass was growing.[5][6]

Paleontology

The earliestLepidopterafossils date to theTriassic-Jurassicboundary, around 200million years ago.[7]Butterflies evolved from moths, so while the butterflies aremonophyletic(forming a singleclade), the moths are not. The oldest known butterfly isProtocoeliades kristensenifrom thePalaeoceneagedFur Formationof Denmark, approximately 55million years old, which belongs to the familyHesperiidae(skippers).[8]Molecular clockestimates suggest that butterflies originated sometime in the LateCretaceous,but only significantly diversified during the Cenozoic,[9][1]with one study suggesting a North American origin for the group.[1]The oldest American butterfly is theLate EoceneProdryas persephonefrom theFlorissant Fossil Beds,[10][11]approximately 34million years old.[12]

- Butterfly fossils

-

Lithopsyche antiqua,anEarly Oligocenebutterfly from the Bembridge Marls,Isle of Wight,1889 engraving

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Butterflies are scientifically classified in themacrolepidopteransubordercladeRhopalocera from theorderLepidoptera,which also includesmoths.[citation needed]Traditionally, butterflies have been divided into thesuperfamilyPapilionoideaexcluding the smaller groups of theHesperiidae(skippers) and the more moth-likeHedylidaeof America.Phylogeneticanalysis suggests that the traditional Papilionoidea isparaphyleticwith respect to the other two groups, so they should both be included within Papilionoidea, to form a single butterfly group, thereby synonymous with the cladeRhopalocera.[13][14]

| Family | Common name | Characteristics | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hedylidae | American moth-butterflies | Small, brown, likegeometrid moths;antennaenot clubbed; long slim abdomen |

|

| Hesperiidae | Skippers | Small, darting flight; clubs on antennae hooked backwards |

|

| Lycaenidae | Blues, coppers, hairstreaks | Small, brightly coloured; often have false heads with eyespots and small tails resembling antennae |

|

| Nymphalidae | Brush-footed or four-footed butterflies | Usually have reduced forelegs, so appear four-legged; often brightly coloured |

|

| Papilionidae | Swallowtails | Often have 'tails' on wings; caterpillar generates foul taste withosmeteriumorgan; pupa supported by silk girdle |

|

| Pieridae | Whites and allies | Mostly white, yellow or orange; some serious pests ofBrassica;pupa supported by silk girdle |

|

| Riodinidae | Metalmarks | Often have metallic spots on wings; often conspicuously coloured with black, orange and blue |

|

Biology

General description

Butterfly adults are characterized by their four scale-covered wings, which give the Lepidoptera their name (Ancient Greekλεπίς lepís, scale + πτερόν pterón, wing). These scales give butterfly wings their colour: they are pigmented withmelaninsthat give them blacks and browns, as well asuric acidderivatives andflavonesthat give them yellows, but many of the blues, greens, reds andiridescent coloursare created bystructural colorationproduced by the micro-structures of the scales and hairs.[15][16][17][18]

As in all insects, the body is divided into three sections: the head,thorax,andabdomen.The thorax is composed of three segments, each with a pair of legs. In most families of butterfly the antennae are clubbed, unlike those ofmothswhich may be threadlike or feathery. The long proboscis can be coiled when not in use for sipping nectar from flowers.[19]

Nearly all butterflies arediurnal,have relatively bright colours, and hold their wings vertically above their bodies when at rest, unlike the majority of moths which fly by night, are oftencrypticallycoloured (well camouflaged), and either hold their wings flat (touching the surface on which the moth is standing) or fold them closely over their bodies. Some day-flying moths, such as thehummingbird hawk-moth,[20]are exceptions to these rules.[19][21]

Butterflylarvae,caterpillars,have a hard (sclerotised) head with strong mandibles used for cutting their food, most often leaves. They have cylindrical bodies, with ten segments to the abdomen, generally with short prolegs on segments 3–6 and 10; the three pairs of true legs on the thorax have five segments each.[19]Many are well camouflaged; others are aposematic with bright colours and bristly projections containing toxic chemicals obtained from their food plants. Thepupaor chrysalis, unlike that of moths, is not wrapped in a cocoon.[19]

Many butterflies aresexually dimorphic.Most butterflies have theZW sex-determination systemwhere females are the heterogametic sex (ZW) and males homogametic (ZZ).[22]

Distribution and migration

Butterflies are distributed worldwide except Antarctica, totalling some 18,500 species.[23]Of these, 775 areNearctic;7,700Neotropical;1,575Palearctic;3,650Afrotropical;and 4,800 are distributed across the combinedOrientalandAustralian/Oceaniaregions.[23]Themonarch butterflyis native to the Americas, but in the nineteenth century or before, spread across the world, and is now found in Australia, New Zealand, other parts of Oceania, and theIberian Peninsula.It is not clear how it dispersed; adults may have been blown by the wind or larvae or pupae may have been accidentally transported by humans, but the presence of suitable host plants in their new environment was a necessity for their successful establishment.[24]

Many butterflies, such as thepainted lady,monarch, and severaldanainemigrate for long distances. These migrations take place over a number of generations and no single individual completes the whole trip. The eastern North American population of monarchs can travel thousands of miles south-west tooverwintering sites in Mexico.There is a reverse migration in the spring.[25][26]It has recently been shown that the British painted lady undertakes a 9,000-mile round trip in a series of steps by up to six successive generations, from tropical Africa to the Arctic Circle — almost double the length of the famous migrations undertaken by monarch.[27]Spectacular large-scale migrations associated with themonsoonare seen in peninsular India.[28]Migrations have been studied in more recent times using wing tags and also usingstable hydrogen isotopes.[29][30]

Butterflies navigate using a time-compensated sun compass. They can see polarized light and therefore orient even in cloudy conditions. The polarized light near the ultraviolet spectrum appears to be particularly important.[31][32]Many migratory butterflies live in semi-arid areas where breeding seasons are short.[33]The life histories of their host plants also influence butterfly behaviour.[34]

Life cycle

Butterflies in their adult stage can live from a week to nearly a year depending on the species. Many species have long larval life stages while others can remaindormantin their pupal or egg stages and thereby survive winters.[35]TheMelissa Arctic(Oeneis melissa) overwinters twice as a caterpillar.[36]Butterflies may have one or more broods per year. The number of generations per year varies fromtemperatetotropical regionswith tropical regions showing a trend towardsmultivoltinism.[37]

Courtshipis often aerial and often involvespheromones.Butterflies then land on the ground or on a perch to mate.[19]Copulation takes place tail-to-tail and may last from minutes to hours. Simple photoreceptor cells located at the genitals are important for this and other adult behaviours.[38]The male passes aspermatophoreto the female; to reduce sperm competition, he may cover her with his scent, or in some species such as the Apollos (Parnassius)plugs her genital openingto prevent her from mating again.[39]

The vast majority of butterflies have a four-stage life cycle:egg,larva(caterpillar),pupa(chrysalis) andimago(adult). In the generaColias,Erebia,Euchloe,andParnassius,a small number of species are known that reproducesemi-parthenogenetically;when the female dies, a partially developed larva emerges from her abdomen.[40]

Eggs

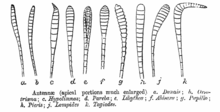

Butterfly eggs are protected by a hard-ridged outer layer of shell, called thechorion.This is lined with a thin coating of wax which prevents the egg from drying out before the larva has had time to fully develop. Each egg contains a number of tiny funnel-shaped openings at one end, calledmicropyles;the purpose of these holes is to allow sperm to enter and fertilize the egg. Butterfly eggs vary greatly in size and shape between species, but are usually upright and finely sculptured. Some species lay eggs singly, others in batches. Many females produce between one hundred and two hundred eggs.[40]

Butterfly eggs are fixed to a leaf with a special glue which hardens rapidly. As it hardens it contracts, deforming the shape of the egg. This glue is easily seen surrounding the base of every egg forming a meniscus. The nature of the glue has been little researched but in the case ofPieris brassicae,it begins as a pale yellow granular secretion containing acidophilic proteins. This is viscous and darkens when exposed to air, becoming a water-insoluble, rubbery material which soon sets solid.[41]Butterflies in the genusAgathymusdo not fix their eggs to a leaf; instead, the newly laid eggs fall to the base of the plant.[42]

Eggs are almost invariably laid on plants. Each species of butterfly has its own host plant range and while some species of butterfly are restricted to just one species of plant, others use a range of plant species, often including members of a common family.[43]In some species, such as thegreat spangled fritillary,the eggs are deposited close to but not on the food plant. This most likely happens when the egg overwinters before hatching and where the host plant loses its leaves in winter, as dovioletsin this example.[44]

The egg stage lasts a few weeks in most butterflies, but eggs laid close to winter, especially in temperate regions, go through adiapause(resting) stage, and the hatching may take place only in spring.[45]Some temperate region butterflies, such as theCamberwell beauty,lay their eggs in the spring and have them hatch in the summer.[46]

Caterpillar larva

Butterfly larvae, or caterpillars, consume plant leaves and spend practically all of their time searching for and eating food. Although most caterpillars are herbivorous, a few species arepredators:Spalgis epiuseatsscale insects,[47]while lycaenids such asLiphyra brassolisaremyrmecophilous,eating ant larvae.[48]

Some larvae, especially those of theLycaenidae,formmutual associationswith ants. They communicate with the ants using vibrations that are transmitted through thesubstrateas well as using chemical signals.[49][50]The ants provide some degree of protection to these larvae and they in turn gatherhoneydew secretions.Large blue(Phengaris arion) caterpillars trickMyrmicaants into taking them back to theant colonywhere they feed on the ant eggs and larvae in a parasitic relationship.[51]

Caterpillars mature through a series of developmental stages known asinstars.Near the end of each stage, the larva undergoes a process calledapolysis,mediated by the release of a series ofneurohormones.During this phase, thecuticle,a tough outer layer made of a mixture ofchitinand specializedproteins,is released from the softerepidermisbeneath, and the epidermis begins to form a new cuticle. At the end of each instar, the larvamoults,the old cuticle splits and the new cuticle expands, rapidly hardening and developing pigment.[52]Development of butterfly wing patterns begins by the last larval instar.

Caterpillars have short antennae and severalsimple eyes.Themouthpartsare adapted for chewing with powerful mandibles and a pair of maxillae, each with a segmented palp. Adjoining these is the labium-hypopharynx which houses a tubular spinneret which is able to extrude silk.[15]Caterpillars such as those in the genusCalpodes(family Hesperiidae) have a specialized tracheal system on the 8th segment that function as a primitive lung.[53]Butterfly caterpillars have three pairs of true legs on the thoracic segments and up to six pairs ofprolegsarising from the abdominal segments. These prolegs have rings of tiny hooks called crochets that are engaged hydrostatically and help the caterpillar grip the substrate.[54]The epidermis bears tufts ofsetae,the position and number of which help in identifying the species. There is also decoration in the form of hairs, wart-like protuberances, horn-like protuberances and spines. Internally, most of the body cavity is taken up by the gut, but there may also be large silk glands, and special glands which secrete distasteful or toxic substances. The developing wings are present in later stage instars and thegonadsstart development in the egg stage.[15]

Pupa

When the larva is fully grown, hormones such asprothoracicotropic hormone(PTTH) are produced. At this point the larva stops feeding, and begins "wandering" in the quest for a suitable pupation site, often the underside of a leaf or other concealed location. There it spins a button of silk which it uses to fasten its body to the surface and moults for a final time. While some caterpillars spin acocoonto protect the pupa, most species do not. The naked pupa, often known as a chrysalis, usually hangs head down from the cremaster, a spiny pad at the posterior end, but in some species a silken girdle may be spun to keep the pupa in a head-up position.[40]Most of the tissues and cells of the larva are broken down inside the pupa, as the constituent material is rebuilt into the imago. The structure of the transforming insect is visible from the exterior, with the wings folded flat on the ventral surface and the two halves of the proboscis, with the antennae and the legs between them.[15]

The pupal transformation into a butterfly throughmetamorphosishas held great appeal to mankind. To transform from the miniature wings visible on the outside of the pupa into large structures usable for flight, the pupal wings undergo rapid mitosis and absorb a great deal of nutrients. If one wing is surgically removed early on, the other three will grow to a larger size. In the pupa, the wing forms a structure that becomes compressed from top to bottom and pleated from proximal to distal ends as it grows, so that it can rapidly be unfolded to its full adult size. Several boundaries seen in the adult colour pattern are marked by changes in the expression of particular transcription factors in the early pupa.[55]

Adult

The reproductive stage of the insect is the winged adult orimago.The surface of both butterflies and moths is covered by scales, each of which is an outgrowth from a singleepidermalcell. The head is small and dominated by the two largecompound eyes.These are capable of distinguishing flower shapes or motion but cannot view distant objects clearly. Colour perception is good, especially in some species in the blue/violet range. Theantennaeare composed of many segments and have clubbed tips (unlike moths that have tapering or feathery antennae). The sensory receptors are concentrated in the tips and can detect odours. Taste receptors are located on the palps and on the feet. The mouthparts are adapted to sucking and themandiblesare usually reduced in size or absent. The first maxillae are elongated into a tubularprobosciswhich is curled up at rest and expanded when needed to feed. The first and second maxillae bear palps which function as sensory organs. Some species have a reduced proboscis or maxillary palps and do not feed as adults.[15]

ManyHeliconiusbutterflies also use their proboscis to feed on pollen;[56]in these species only 20% of the amino acids used in reproduction come from larval feeding, which allow them to develop more quickly as caterpillars, and gives them a longer lifespan of several months as adults.[57]

The thorax of the butterfly is devoted to locomotion. Each of the three thoracic segments has two legs (amongnymphalids,the first pair is reduced and the insects walk on four legs). The second and third segments of the thorax bear the wings. The leading edges of the forewings have thick veins to strengthen them, and the hindwings are smaller and more rounded and have fewer stiffening veins. The forewings and hindwings are not hooked together (as they are in moths) but are coordinated by the friction of their overlapping parts. The front two segments have a pair ofspiracleswhich are used in respiration.[15]

The abdomen consists of ten segments and contains the gut and genital organs. The front eight segments have spiracles and the terminal segment is modified for reproduction. The male has a pair of clasping organs attached to a ring structure, and during copulation, a tubular structure is extruded and inserted into the female's vagina. Aspermatophoreis deposited in the female, following which the sperm make their way to a seminal receptacle where they are stored for later use. In both sexes, the genitalia are adorned with various spines, teeth, scales and bristles, which act to prevent the butterfly from mating with an insect of another species.[15]After it emerges from its pupal stage, a butterfly cannot fly until the wings are unfolded. A newly emerged butterfly needs to spend some time inflating its wings withhemolymphand letting them dry, during which time it is extremely vulnerable to predators.[58]

Pattern formation

The colourful patterns on many butterfly wings tell potential predators that they are toxic. Hence, the genetic basis of wingpattern formationcan illuminate both theevolutionof butterflies as well as theirdevelopmental biology.The colour of butterfly wings is derived from tiny structures called scales, each of which have their ownpigments.InHeliconiusbutterflies, there are three types of scales: yellow/white, black, and red/orange/brown scales. Some mechanism of wing pattern formation are now being solved using genetic techniques. For instance, agenecalledcortexdetermines the colour of scales: deletingcortexturned black and red scales yellow. Mutations, e.g.transposon insertionsof thenon-coding DNAaround thecortexgene can turn a black-winged butterfly into a butterfly with a yellow wing band.[59]

Mating

When the butterflyBicyclus anynanais subjected to repeated inbreeding in the laboratory, there is a dramatic decrease in egg hatching.[60]This severeinbreeding depressionis considered to be likely due to a relatively highmutation rateto recessivealleleswith substantial damaging effects and infrequent episodes ofinbreedingin nature that might otherwise purge such mutations.[60]AlthoughB. anynanaexperiences inbreeding depression when forcibly inbred in the laboratory it recovers within a few generation when allowed to breed freely.[61]During mate selection, adult females do not innately avoid or learn to avoid siblings, implying that such detection may not be critical to reproductive fitness.[61]Inbreeding may persist inB anynanabecause the probability of encountering close relatives is rare in nature; that is, movement ecology may mask the deleterious effect of inbreeding resulting in relaxation of selection for active inbreeding avoidance behaviors.

Behaviour

Butterflies feed primarily onnectarfrom flowers. Some also derive nourishment frompollen,[62]tree sap, rotting fruit, dung, decaying flesh, and dissolved minerals in wet sand or dirt. Butterflies are important as pollinators for some species of plants. In general, they do not carry as much pollen load asbees,but they are capable of moving pollen over greater distances.[63]Flower constancyhas been observed for at least one species of butterfly.[64]

Adult butterflies consume only liquids, ingested through the proboscis. They sip water from damp patches for hydration and feed on nectar from flowers, from which they obtain sugars for energy, andsodiumand other minerals vital for reproduction. Several species of butterflies need more sodium than that provided by nectar and are attracted by sodium in salt; they sometimes land on people, attracted by the salt in human sweat. Some butterflies also visit dung and scavenge rotting fruit or carcasses to obtain minerals and nutrients. In many species, thismud-puddlingbehaviour is restricted to the males, and studies have suggested that the nutrients collected may be provided as anuptial gift,along with the spermatophore, during mating.[65]

Inhilltopping,males of some species seek hilltops and ridge tops, which they patrol in search for females. Since it usually occurs in species with low population density, it is assumed these landscape points are used as meeting places to find mates.[66]

Butterflies use their antennae to sense the air for wind and scents. The antennae come in various shapes and colours; the hesperiids have a pointed angle or hook to the antennae, while most other families show knobbed antennae. The antennae are richly covered with sensory organs known assensillae.A butterfly's sense of taste is coordinated by chemoreceptors on thetarsi,or feet, which work only on contact, and are used to determine whether an egg-laying insect's offspring will be able to feed on a leaf before eggs are laid on it.[67]Many butterflies use chemical signals,pheromones;some have specialized scent scales (androconia) or other structures (coremataor "hair pencils" in the Danaidae).[68]Vision is well developed in butterflies and most species are sensitive to the ultraviolet spectrum. Many species show sexual dimorphism in the patterns of UV reflective patches.[69]Colour vision may be widespread but has been demonstrated in only a few species.[70][71]Some butterflies have organs of hearing and some species makestridulatoryand clicking sounds.[72]

Many species of butterfly maintain territories and actively chase other species or individuals that may stray into them. Some species will bask or perch on chosen perches. The flight styles of butterflies are often characteristic and some species have courtship flight displays. Butterflies can only fly when their temperature is above 27 °C (81 °F); when it is cool, they can position themselves to expose the underside of the wings to the sunlight to heat themselves up. If their body temperature reaches 40 °C (104 °F), they can orientate themselves with the folded wings edgewise to the sun.[73]Basking is an activity which is more common in the cooler hours of the morning. Some species have evolved dark wingbases to help in gathering more heat and this is especially evident in alpine forms.[74]

As in many other insects, theliftgenerated by butterflies is more than can be accounted for by steady-state, non-transitoryaerodynamics.Studies usingVanessa atalantain awind tunnelshow that they use a wide variety of aerodynamic mechanisms to generate force. These includewake capture,vorticesat the wing edge, rotational mechanisms and theWeis-Fogh'clap-and-fling' mechanism. Butterflies are able to change from one mode to another rapidly.[75]

Ecology

Parasitoids, predators, and pathogens

Butterflies are threatened in their early stages byparasitoidsand in all stages by predators, diseases and environmental factors.Braconidand other parasitic wasps lay their eggs in lepidopteran eggs or larvae and the wasps' parasitoid larvae devour their hosts, usually pupating inside or outside the desiccated husk. Most wasps are very specific about their host species and some have been used as biological controls of pest butterflies like thelarge white butterfly.[76]When thesmall cabbage whitewas accidentally introduced to New Zealand, it had no natural enemies. In order to control it, some pupae that had been parasitised by a chalcid wasp were imported, and natural control was thus regained.[77]Some flies lay their eggs on the outside of caterpillars and the newly hatched fly larvae bore their way through the skin and feed in a similar way to the parasitoid wasp larvae.[78]Predators of butterflies include ants, spiders, wasps, and birds.[79]

Caterpillars are also affected by a range of bacterial, viral and fungal diseases, and only a small percentage of the butterfly eggs laid ever reach adulthood.[78]The bacteriumBacillus thuringiensishas been used in sprays to reduce damage to crops by the caterpillars of the large white butterfly, and theentomopathogenic fungusBeauveria bassianahas proved effective for the same purpose.[80]

Endangered species

Queen Alexandra's birdwing,found inPapua New Guinea,is the largest butterfly in the world. The species isendangered,and is one of only three insects (the other two being butterflies as well) to be listed onAppendix IofCITES,making international trade illegal.[81]

Black grass-dart butterfly(Ocybadistes knightorum)is a butterfly of the familyHesperiidae.It is endemic toNew South Wales.It has a very limited distribution in theBoambeearea.

Defences

Butterflies protect themselves from predators by a variety of means.

Chemical defences are widespread and are mostly based on chemicals of plant origin. In many cases the plants themselves evolved these toxic substances asprotectionagainst herbivores. Butterflies have evolved mechanisms to sequester these plant toxins and use them instead in their own defence.[82]These defence mechanisms are effective only if they are well advertised; this has led to the evolution of bright colours in unpalatable butterflies (aposematism). This signal is commonlymimickedby other butterflies, usually only females. ABatesian mimicimitates another species to enjoy the protection of that species' aposematism.[83]Thecommon Mormonof India has female morphs which imitate the unpalatable red-bodied swallowtails, thecommon roseand thecrimson rose.[84]Müllerian mimicryoccurs when aposematic species evolve to resemble each other, presumably to reduce predator sampling rates;Heliconiusbutterflies from the Americas are a good example.[83]

Camouflageis found in many butterflies. Some like the oakleaf butterfly andautumn leafare remarkable imitations of leaves.[85]As caterpillars, many defend themselves by freezing and appearing like sticks or branches.[86]Others havedeimaticbehaviours, such as rearing up and waving their front ends which are marked with eyespots as if they were snakes.[87]Some papilionid caterpillars such as the giant swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes) resemble bird droppings so as to be passed over by predators.[88]Some caterpillars have hairs and bristly structures that provide protection while others are gregarious and form dense aggregations.[83]Some species aremyrmecophiles,formingmutualistic associationswithantsand gaining their protection.[89]Behavioural defences include perching and angling the wings to reduce shadow and avoid being conspicuous. Some femaleNymphalidbutterflies guard their eggs from parasitoidalwasps.[90]

The Lycaenidae have a false head consisting of eyespots and small tails (false antennae) to deflect attack from the more vital head region. These may also cause ambush predators such as spiders to approach from the wrong end, enabling the butterflies to detect attacks promptly.[91][92]Many butterflies haveeyespotson the wings; these too may deflect attacks, or may serve to attract mates.[55][93]

Auditory defences can also be used, which in the case of thegrizzled skipperrefers to vibrations generated by the butterfly upon expanding its wings in an attempt to communicate with ant predators.[94]

Many tropical butterflies haveseasonal formsfor dry and wet seasons.[95][96]These are switched by the hormoneecdysone.[97]The dry-season forms are usually more cryptic, perhaps offering better camouflage when vegetation is scarce. Dark colours in wet-season forms may help to absorb solar radiation.[98][99][93]

Butterflies without defences such as toxins or mimicry protect themselves through a flight that is more bumpy and unpredictable than in other species. It is assumed this behavior makes it more difficult for predators to catch them, and is caused by theturbulencecreated by the small whirlpools formed by the wings during flight.[100]

-

Giant swallowtailcaterpillar everting itsosmeteriumin defence; it is alsomimetic,resembling a bird dropping.

-

Eyespots ofspeckled wood(Pararge aegeria) distract predators from attacking the head. This insect can still fly with a damaged left hindwing.

Declining numbers

Declining butterfly populations have been noticed in many areas of the world, and this phenomenon is consistent with therapidly decreasing insect populations around the world.At least in the Western United States, this collapse in the number of most species of butterflies has been determined to be driven byglobal climate change,specifically, by warmer autumns.[102][103]

In culture

In art and literature

Butterflies have appeared in art from 3500 years ago inancient Egypt.[104]In hunting scenes, butterflies were sometimes included in a way that suggested life, freedom, and the strength to escape capture, creating a balance to scenes concerned with death and upholdingma'at.They also were suggestive of regeneration or rebirth and protection. Certain butterflies, such as thetiger butterfly,may have been associated with solar deities, particularlyRa.The tiger butterfly also would have a particular resemblance to theankh,due to its black body and wingtips, that was likely noted by the Ancient Egyptians. Butterflies may also have been understood as one of the deceased's guides in the afterlife.[105]

In the ancientMesoamericancity ofTeotihuacan,the brilliantly coloured image of the butterfly was carved into many temples, buildings, jewellery, and emblazoned onincense burners.The butterfly was sometimes depicted with the maw of ajaguar,and some species were considered to be the reincarnations of the souls of dead warriors. The close association of butterflies with fire and warfare persisted into theAztec civilisation;evidence of similar jaguar-butterfly images has been found among theZapotecandMaya civilisations.[106]

Butterflies are widely used in objects of art and jewellery: mounted in frames, embedded in resin, displayed in bottles, laminated in paper, and used in some mixed media artworks and furnishings.[107]TheNorwegiannaturalistKjell Sandvedcompiled a photographicButterfly Alphabetcontaining all 26 letters and the numerals 0 to 9 from the wings of butterflies.[108]

SirJohn Tennieldrew a famous illustration ofAlicemeeting acaterpillarforLewis Carroll'sAlice in Wonderland,c. 1865. The caterpillar is seated on a toadstool and is smoking ahookah;the image can be read as showing either the forelegs of the larva, or as suggesting a face with protruding nose and chin.[5]Eric Carle's children's bookThe Very Hungry Caterpillarportrays the larva as an extraordinarily hungry animal, while also teaching children how to count (to five) and the days of the week.[5]

A butterfly appeared in one ofRudyard Kipling'sJust So Stories,"The Butterfly that Stamped".[109]

One of the most popular, and most often recorded, songs bySweden's eighteenth-century bard,Carl Michael Bellman,is "Fjäriln vingad syns på Haga"(The butterfly wingèd is seen in Haga), one of hisFredman's Songs.[110]

Madam Butterflyis a 1904operabyGiacomo Pucciniabout a romantic young Japanese bride who is deserted by her American officer husband soon after they are married. It was based onJohn Luther Long's short story written in 1898.[111]

In mythology and folklore

According toLafcadio Hearn,a butterfly was seen in Japan as the personification of a person's soul; whether they be living, dying, or already dead. One Japanese superstition says that if a butterfly enters your guest room and perches behind the bamboo screen, the person whom you most love is coming to see you. Large numbers of butterflies are viewed as badomens.WhenTaira no Masakadowas secretly preparing his famous revolt, a vast a swarm of butterflies appeared inKyoto.The people were frightened, thinking the apparition to be a portent of coming evil.[112]

Diderot'sEncyclopédiecites butterflies as a symbol for the soul. A Roman sculpture depicts a butterfly exiting the mouth of a dead man, representing the Roman belief that the soul leaves through the mouth.[113]In line with this, the ancient Greek word for "butterfly" is ψυχή (psȳchē), which primarily means "soul" or "mind".[114]According toMircea Eliade,some of theNagasofManipurclaim ancestry from a butterfly.[115]In some cultures, butterflies symboliserebirth.[116]The butterfly is a symbol of beingtransgender,because of the transformation from caterpillar to winged adult.[117]In the English county ofDevon,people once hurried to kill the first butterfly of the year, to avoid a year of bad luck.[118]In the Philippines, a lingering black or dark butterfly or moth in the house is taken to mean an impending or recent death in the family.[119]Several American states have chosen anofficial state butterfly.[120]

Collecting, recording, and rearing

"Collecting" means preserving dead specimens, not keeping butterflies as pets.[121][122]Collecting butterflies was once a popular hobby; it has now largely been replaced by photography, recording, and rearing butterflies for release into the wild.[5][dubious–discuss][full citation needed]The zoological illustratorFrederick William Frohawksucceeded in rearing all the butterfly species found in Britain, at a rate of four per year, to enable him to draw every stage of each species. He published the results in the folio sized handbookThe Natural History of British Butterfliesin 1924.[5]

Butterflies andmothscan be reared for recreation or for release.[123]

In technology

Study of thestructural colorationof the wing scales of swallowtail butterflies has led to the development of more efficientlight-emitting diodes,[124]and is inspiringnanotechnologyresearch to produce paints that do not use toxic pigments and the development of new display technologies.[125]

References

- ^abcKawahara, Akito Y.; Storer, Caroline; Carvalho, Ana Paula S.; Plotkin, David M.; Condamine, Fabien L.; Braga, Mariana P.; Ellis, Emily A.; St Laurent, Ryan A.; Li, Xuankun; Barve, Vijay; Cai, Liming; Earl, Chandra; Frandsen, Paul B.; Owens, Hannah L.; Valencia-Montoya, Wendy A. (15 May 2023)."A global phylogeny of butterflies reveals their evolutionary history, ancestral hosts and biogeographic origins".Nature Ecology & Evolution.7(6): 903–913.Bibcode:2023NatEE...7..903K.doi:10.1038/s41559-023-02041-9.ISSN2397-334X.PMC10250192.PMID37188966.

- ^"Butterfly Life Cycle".For Educators.Retrieved16 July2024.

- ^McClure, Melanie; Clerc, Corentin; Desbois, Charlotte; Meichanetzoglou, Aimilia; Cau, Marion; Bastin-Héline, Lucie; Bacigalupo, Javier; Houssin, Céline; Pinna, Charline; Nay, Bastien; Llaurens, Violaine (24 April 2019)."Why has transparency evolved in aposematic butterflies? Insights from the largest radiation of aposematic butterflies, the Ithomiini".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.286(1901).doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2769.ISSN0962-8452.PMC6501930.PMID30991931.

- ^"Benefits of Insects to Humans".Smithsonian Institution.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2021.Retrieved24 September2021.

- ^abcdefMarren, Peter;Mabey, Richard(2010).Bugs Britannica.Chatto and Windus. pp. 196–205.ISBN978-0-7011-8180-2.

- ^Donald A. Ringe,A Linguistic History of English: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic(Oxford: Oxford, 2003), 232.

- ^Eldijk, Timo J. B. van; Wappler, Torsten; Strother, Paul K.; Weijst, Carolien M. H. van der; Rajaei, Hossein; Visscher, Henk; Schootbrugge, Bas van de (1 January 2018)."A Triassic-Jurassic window into the evolution of Lepidoptera".Science Advances.4(1): e1701568.Bibcode:2018SciA....4.1568V.doi:10.1126/sciadv.1701568.ISSN2375-2548.PMC5770165.PMID29349295.

- ^De Jong, Rienk (9 August 2016)."Reconstructing a 55-million-year-old butterfly (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae)".European Journal of Entomology.113:423–428.doi:10.14411/eje.2016.055.

- ^Chazot, Nicolas; Wahlberg, Niklas; Freitas, André Victor Lucci; Mitter, Charles; Labandeira, Conrad; Sohn, Jae-Cheon; Sahoo, Ranjit Kumar; Seraphim, Noemy; de Jong, Rienk; Heikkilä, Maria (25 February 2019)."Priors and Posteriors in Bayesian Timing of Divergence Analyses: The Age of Butterflies Revisited".Systematic Biology.68(5): 797–813.doi:10.1093/sysbio/syz002.ISSN1063-5157.PMC6893297.PMID30690622.Archivedfrom the original on 19 July 2021.Retrieved9 July2021.

- ^Meyer, Herbert William; Smith, Dena M. (2008).Paleontology of the Upper Eocene Florissant Formation, Colorado.Geological Society of America. p. 6.ISBN978-0-8137-2435-5.Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^"Lepidoptera – Latest Classification".Discoveries in Natural History & Exploration.University of California. Archived fromthe originalon 7 April 2012.Retrieved15 July2011.

- ^McIntosh, W. C.; et al. (1992). "Calibration of the Latest Eocene-Oligocene geomagnetic Polarity Time Scale Using 40Ar/39Ar Dated Ignimbrites".Geology.20(5): 459–463.Bibcode:1992Geo....20..459M.doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1992)020<0459:cotleo>2.3.co;2.

- ^Heikkilä, M.; Kaila, L.; Mutanen, M.; Peña, C.; Wahlberg, N. (2012)."Cretaceous Origin and Repeated Tertiary Diversification of the Redefined Butterflies".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.279(1731): 1093–1099.doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1430.PMC3267136.PMID21920981.

- ^Kawahara, A. Y.; Breinholt, J. W. (2014)."Phylogenomics Provides Strong Evidence for Relationships of Butterflies And Moths".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.281(1788): 20140970.doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0970.PMC4083801.PMID24966318.

- ^abcdefgCulin, Joseph."Lepidopteran: Form and function".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 21 September 2017.Retrieved8 September2015.

- ^Mason, C. W. (1927). "Structural Colors in Insects. II".The Journal of Physical Chemistry.31(3): 321–354.doi:10.1021/j150273a001.

- ^Vukusic, P.; J. R. Sambles & H. Ghiradella (2000). "Optical Classification of Microstructure in Butterfly Wing-scales".Photonics Science News.6:61–66.

- ^Prum, R.; Quinn, T.; Torres, R. (February 2006)."Anatomically Diverse Butterfly Scales all Produce Structural Colours by Coherent Scattering".The Journal of Experimental Biology.209(Pt 4): 748–65.doi:10.1242/jeb.02051.hdl:1808/1600.ISSN0022-0949.PMID16449568.

- ^abcdeGullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S. (2014).The Insects: An Outline of Entomology(5 ed.). Wiley. pp. 523–524.ISBN978-1-118-84616-2.Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Herrera, Carlos M. (1992). "Activity Pattern and Thermal Biology of a Day-Flying Hawkmoth (Macroglossum stellatarum) under Mediterranean summer conditions ".Ecological Entomology.17(1): 52–56.Bibcode:1992EcoEn..17...52H.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1992.tb01038.x.hdl:10261/44693.S2CID85320151.

- ^"Butterflies and Moths (Order Lepidoptera)".Amateur Entomologists' Society.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2015.Retrieved13 September2015.

- ^Traut, W.; Marec, F. (August 1997). "Sex Chromosome Differentiation in Some Species of Lepidoptera (Insecta)".Chromosome Research.5(5): 283–91.doi:10.1023/B:CHRO.0000038758.08263.c3.ISSN0967-3849.PMID9292232.S2CID21995492.

- ^abWilliams, Ernest; Adams, James; Snyder, John."Frequently Asked Questions".The Lepidopterists' Society. Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2015.Retrieved9 September2015.

- ^"Global Distribution".Monarch Lab. Archived fromthe originalon 6 October 2015.Retrieved9 September2015.

- ^"Chill Turns Monarchs North; Cold Weather Flips Butterflies' Migratory Path".Science News.183(6). 23 March 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2013.Retrieved5 August2014.

- ^Pyle, Robert Michael (1981).National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Butterflies.Alfred A. Knopf. pp.712–713.ISBN978-0-394-51914-2.

- ^"Butterfly Conservation: Secrets of Painted Lady migration unveiled".BirdGuides Ltd. 22 October 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2012.Retrieved22 October2012.

- ^Williams, C. B. (1927). "A Study of Butterfly Migration in South India and Ceylon, based largely on records by Messrs. G. Evershed, E. E. Green, J. C. F. Fryer and W. Ormiston".Transactions of the Entomological Society of London.75:1–33.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1927.tb00054.x.

- ^Urquhart, F. A.; Urquhart, N. R. (1977). "Overwintering Areas and Migratory Routes of the Monarch butterfly (Danaus p. plexippus,Lepidoptera: Danaidae) in North America, with Special Reference to the Western Population ".Can. Entomol.109(12): 1583–1589.doi:10.4039/Ent1091583-12.S2CID86198255.

- ^Wassenaar, L.I.; Hobson, K.A. (1998)."Natal Origins of Migratory Monarch Butterflies at Wintering Colonies in Mexico: New Isotopic Evidence".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.95(26): 15436–9.Bibcode:1998PNAS...9515436W.doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15436.PMC28060.PMID9860986.

- ^Reppert, Steven M.; Zhu, Haisun; White, Richard H. (2004)."Polarized light Helps Monarch Butterflies Navigate".Current Biology.14(2): 155–158.Bibcode:2004CBio...14..155R.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.034.PMID14738739.S2CID18022063.

- ^Sauman, Ivo; Briscoe, Adriana D.; Zhu, Haisun; Shi, Dingding; Froy, Oren; Stalleicken, Julia; Yuan, Quan; Casselman, Amy; Reppert, Steven M.; et al. (2005)."Connecting the Navigational Clock to Sun Compass Input in Monarch Butterfly Brain".Neuron.46(3): 457–467.doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.014.PMID15882645.S2CID17755509.

- ^Southwood, T. R. E. (1962). "Migration of terrestrial arthropods in relation to habitat".Biol. Rev.37(2): 171–214.doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1962.tb01609.x.S2CID84711127.

- ^Dennis, R L H; Shreeve, Tim G.; Arnold, Henry R.; Roy, David B. (2005). "Does Diet Breadth Control Herbivorous Insect Distribution Size? Life History and Resource Outlets for Specialist Butterflies".Journal of Insect Conservation.9(3): 187–200.doi:10.1007/s10841-005-5660-x.S2CID20605146.

- ^Powell, J. A. (1987)."Records of Prolonged Diapause in Lepidoptera".Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera.25(2): 83–109.doi:10.5962/p.266734.S2CID248727391.

- ^"Melissa Arctic".Butterflies and Moths of North America.Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2015.Retrieved15 September2015.

- ^Timothy Duane Schowalter (2011).Insect Ecology: An Ecosystem Approach.Academic Press. p. 159.ISBN978-0-12-381351-0.Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Arikawa, Kentaro (2001)."Hindsight of Butterflies: The Papilio butterfly has light sensitivity in the genitalia, which appears to be crucial for reproductive behavior".BioScience.51(3): 219–225.doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0219:HOB]2.0.CO;2.

- ^Schlaepfer, Gloria G. (2006).Butterflies.Marshall Cavendish. p.52.ISBN978-0-7614-1745-3.

- ^abcCapinera, John L. (2008).Encyclopedia of Entomology.Springer Science & Business Media. p. 640.ISBN978-1-4020-6242-1.Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Beament, J.W.L.; Lal, R. (1957). "Penetration Through the Egg-shell ofPieris brassicae".Bulletin of Entomological Research.48(1): 109–125.doi:10.1017/S0007485300054134.

- ^Scott, James A. (1992).The Butterflies of North America: A Natural History and Field Guide.Stanford University Press. p. 121.ISBN978-0-8047-2013-7.Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Capinera, John L. (2008).Encyclopedia of Entomology.Springer Science & Business Media. p. 676.ISBN978-1-4020-6242-1.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Shepard, Jon; Guppy, Crispin (2011).Butterflies of British Columbia: Including Western Alberta, Southern Yukon, the Alaska Panhandle, Washington, Northern Oregon, Northern Idaho, and Northwestern Montana.UBC Press. p. 55.ISBN978-0-7748-4437-6.Archivedfrom the original on 13 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^"British Butterflies: Education: Butterflies in Winter".Archived fromthe originalon 7 January 2017.Retrieved12 September2015.

- ^"Camberwell Beauty".NatureGate. Archived fromthe originalon 21 April 2017.Retrieved12 September2015.

- ^Venkatesha, M. G.; Shashikumar, L.; Gayathri Devi, S.S. (2004). "Protective Devices of the Carnivorous Butterfly,Spalgis epius(Westwood) (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) ".Current Science.87(5): 571–572.

- ^Bingham, C.T.(1907).The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma.Vol. II (1st ed.). London:Taylor and Francis, Ltd.

- ^Devries, P. J. (1988). "The larval Ant-organs of Thisbe irenea (Lepidoptera: Riodinidae) and Their Effects Upon Attending Ants".Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.94(4): 379–393.doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1988.tb01201.x.

- ^Devries, P. J. (June 1990). "Enhancement of Symbioses Between Butterfly Caterpillars and Ants by Vibrational Communication".Science.248(4959): 1104–1106.Bibcode:1990Sci...248.1104D.doi:10.1126/science.248.4959.1104.PMID17733373.S2CID35812411.

- ^Thomas, Jeremy; Schönrogge, Karsten; Bonelli, Simona; Barbero, Francesca; Balletto, Emilio (2010)."Corruption of Ant Acoustical Signals by Mimetic Social Parasites".Communicative and Integrative Biology.3(2): 169–171.doi:10.4161/cib.3.2.10603.PMC2889977.PMID20585513.

- ^Klowden, Marc J. (2013).Physiological Systems in Insects.Academic Press. p. 114.ISBN978-0-12-415970-9.Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Locke, Michael (1997)."Caterpillars have evolved lungs for hemocyte gas exchange".Journal of Insect Physiology.44(1): 1–20.Bibcode:1997JInsP..44....1L.doi:10.1016/s0022-1910(97)00088-7.PMID12770439.Archivedfrom the original on 19 July 2021.Retrieved19 June2018.

- ^"Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum".Larva Legs.Chicago Academy of Sciences. Archived fromthe originalon 19 March 2012.Retrieved7 June2012.

- ^abBrunetti, Craig R.; Selegue, Jayne E.; Monteiro, Antonia; French, Vernon; Brakefield, Paul M.; Carroll, Sean B. (2001)."The Generation and Diversification of Butterfly Eyespot Color Patterns".Current Biology.11(20): 1578–1585.Bibcode:2001CBio...11.1578B.doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00502-4.PMID11676917.S2CID14290399.

- ^Harpel, D.; Cullen, D. A.; Ott, S. R.; Jiggins, C. D.; Walters, J. R. (2015)."Pollen feeding proteomics: Salivary proteins of the passion flower butterfly, Heliconius melpomene".Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.63:7–13.Bibcode:2015IBMB...63....7H.doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.04.004.hdl:2381/37010.PMID25958827.S2CID39086740.Archivedfrom the original on 19 July 2021.Retrieved8 November2018.

- ^"The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago |Heliconius ethilla(Ethilia Longwing Butterfly) "(PDF).UWI St. Augustine.Archived(PDF)from the original on 28 May 2018.Retrieved28 May2018.

- ^Woodbury, Elton N. (1994).Butterflies of Delmarva.Delaware Nature Society; Tidewater Publishers. p. 22.ISBN978-0-87033-453-5.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Livraghi, Luca; Hanly, Joseph J; Van Bellghem, Steven M; Montejo-Kovacevich, Gabriela; van der Heijden, Eva SM; Loh, Ling Sheng; Ren, Anna; Warren, Ian A; Lewis, James J; Concha, Carolina; Hebberecht, Laura (19 July 2021)."Cortex cis-regulatory switches establish scale colour identity and pattern diversity in Heliconius".eLife.10:e68549.doi:10.7554/eLife.68549.ISSN2050-084X.PMC8289415.PMID34280087.

- ^abSaccheri IJ, Brakefield PM, Nichols RA. "Severe Inbreeding Depression and Rapid Fitness Rebound in the ButterflyBicyclus anynana(Satyridae) ".Evolution.1996 Oct; 50 (5): 2000-2013. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03587.x. PMID 28565613

- ^abRobertson DN, Sullivan TJ, Westerman EL. Lack of sibling avoidance during mate selection in the butterflyBicyclus anynana.Behavioural Processes.2020 Apr; 173: 104062. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2020.104062. Epub 2020 Jan 22. PMID 31981681

- ^Gilbert, L. E. (1972)."Pollen Feeding and Reproductive Biology ofHeliconiusButterflies ".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.69(6): 1402–1407.Bibcode:1972PNAS...69.1403G.doi:10.1073/pnas.69.6.1403.PMC426712.PMID16591992.

- ^Herrera, C. M. (1987)."Components of Pollinator 'Quality': Comparative Analysis of a Diverse Insect Assemblage"(PDF).Oikos.50(1): 79–90.doi:10.2307/3565403.JSTOR3565403.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 25 February 2009.

- ^Goulson, D.;Ollerton, J.; Sluman, C. (1997)."Foraging strategies in the small skipper butterfly,Thymelicus flavus:when to switch? "(PDF).Animal Behaviour.53(5): 1009–1016.doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0390.S2CID620334.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 March 2021.Retrieved24 December2020.

- ^Molleman, Freerk; Grunsven, Roy H. A.; Liefting, Maartje; Zwaan, Bas J.; Brakefield, Paul M. (2005). "Is Male Puddling Behaviour of Tropical Butterflies Targeted at Sodium for Nuptial Gifts or Activity?".Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.86(3): 345–361.doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00539.x.

- ^Gochfeld, Michael; Burger, Joanna (1997).Butterflies of New Jersey: A Guide to Their Status, Distribution, Conservation, and Appreciation.Rutgers University Press. p. 55.ISBN978-0-8135-2355-2.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved15 May2018.

- ^"Article on San Diego Zoo website".Sandiegozoo.org.Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2009.Retrieved30 March2009.

- ^Birch, M. C.; Poppy, G. M. (1990)."Scents and Eversible Scent Structures of Male Moths"(PDF).Annual Review of Entomology.35:25–58.doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.35.1.25.Archived(PDF)from the original on 6 October 2015.Retrieved12 September2015.

- ^Obara, Y.; Hidaki, T. (1968)."Recognition of the Female by the Male, on the Basis of Ultra-Violet Reflection, in the White Cabbage Butterfly,Pieris rapae crucivoraBoisduval ".Proceedings of the Japan Academy.44(8): 829–832.doi:10.2183/pjab1945.44.829.

- ^Hirota, Tadao; Yoshiomi, Yoshiomi (2004)."Color Discrimination on Orientation of FemaleEurema hecabe(Lepidoptera: Pieridae) ".Applied Entomology and Zoology.39(2): 229–233.Bibcode:2004AppEZ..39..229H.doi:10.1303/aez.2004.229.

- ^Kinoshita, Michiyo; Shimada, Naoko; Arikawa, Kentaro (1999)."Color Vision of the Foraging Swallowtail ButterflyPapilio xuthus".The Journal of Experimental Biology.202(2): 95–102.doi:10.1242/jeb.202.2.95.PMID9851899.Archivedfrom the original on 2 November 2018.Retrieved10 August2021.

- ^Swihart, S. L (1967). "Hearing in Butterflies".Journal of Insect Physiology.13(3): 469–472.doi:10.1016/0022-1910(67)90085-6.

- ^"Butterflies Make Best Use of the Sunshine".New Scientist.Vol. 120, no. 1643. 17 December 1988. p. 13.ISSN0262-4079.Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Ellers, J.; Boggs, Carol L. (2002)."The Evolution of Wing Color inColiasButterflies: Heritability, Sex Linkage, and population divergence "(PDF).Evolution.56(4): 836–840.doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[0836:teowci]2.0.co;2.PMID12038541.S2CID8732686.Archived(PDF)from the original on 7 January 2007.Retrieved7 November2006.

- ^Srygley, R. B.; Thomas, A. L. R. (2002). "Aerodynamics of Insect Flight: Flow Visualisations with Free Flying Butterflies Reveal a Variety of Unconventional Lift-Generating Mechanisms".Nature.420(6916): 660–664.Bibcode:2002Natur.420..660S.doi:10.1038/nature01223.PMID12478291.S2CID11435467.

- ^Feltwell, J. (2012).Large White Butterfly: The Biology, Biochemistry and Physiology ofPieris brassicae(Linnaeus).Springer. pp. 401–.ISBN978-94-009-8638-1.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002).International Wildlife Encyclopedia: Brown bear - Cheetah.Marshall Cavendish. p. 416.ISBN978-0-7614-7269-8.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^abAllen, Thomas J. (2005).A Field Guide to Caterpillars.Oxford University Press. p. 15.ISBN978-0-19-803413-1.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^"Parasites and Natural Enemies".University of Minnesota.Archivedfrom the original on 7 October 2015.Retrieved16 October2015.

- ^Feltwell, J. (2012).Large White Butterfly: The Biology, Biochemistry and Physiology ofPieris Brassicae(Linnaeus).Springer. p. 429.ISBN978-94-009-8638-1.Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2016.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^CITES appendices I, II and IIIArchived5 December 2017 at theWayback Machine,official website

- ^Nishida, Ritsuo (2002). "Sequestration of Defensive Substances from Plants by Lepidoptera".Annual Review of Entomology.47:57–92.doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145121.PMID11729069.

- ^abcEdmunds, M. (1974).Defence in Animals.Longman. pp.74–78, 100–113.

- ^Halloran, Kathryn; Wason, Elizabeth (2013)."Papilio polytes".Animal Diversity Web.University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.Archivedfrom the original on 7 October 2015.Retrieved12 September2015.

- ^Robbins, Robert K. (1981). "The" False Head "Hypothesis: Predation and Wing Pattern Variation of Lycaenid Butterflies".American Naturalist.118(5): 770–775.doi:10.1086/283868.S2CID34146954.

- ^Forbes, Peter (2009).Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-17896-8.

- ^Edmunds, Malcolm (2012)."Deimatic Behavior".Springer.Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2013.Retrieved31 December2012.

- ^"Featured Creatures: Giant Swallowtail".University of Florida.Archivedfrom the original on 11 June 2019.Retrieved12 September2015.

- ^Fiedler, K.; Holldobler, B.; Seufert, P. (1996). "Butterflies and Ants: The Communicative Domain".Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences.52:14–24.doi:10.1007/bf01922410.S2CID33081655.

- ^Nafus, D. M.; Schreiner, I. H. (1988). "Parental Care in a Tropical Nymphalid ButterflyHypolimas anomala".Animal Behaviour.36(5): 1425–1443.doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(88)80213-6.S2CID53183529.

- ^Cooper, William E. Jr. (1998). "Conditions Favoring Anticipatory and Reactive Displays Deflecting Predatory Attack".Behavioral Ecology.9(6): 598–604.CiteSeerX10.1.1.928.6688.doi:10.1093/beheco/9.6.598.

- ^Stevens, M. (2005). "The Role of Eyespots as Anti-Predator Mechanisms, Principally Demonstrated in the Lepidoptera".Biological Reviews.80(4): 573–588.doi:10.1017/S1464793105006810.PMID16221330.S2CID24868603.

- ^abBrakefield, PM; Gates, Julie; Keys, Dave; Kesbeke, Fanja; Wijngaarden, Pieter J.; Montelro, Antónia; French, Vernon; Carroll, Sean B.; et al. (1996). "Development, Plasticity and Evolution of Butterfly Eyespot Patterns".Nature.384(6606): 236–242.Bibcode:1996Natur.384..236B.doi:10.1038/384236a0.PMID12809139.S2CID3341270.

- ^Elfferich, Nico W. (1998)."Is the larval and imaginal signalling of Lycaenidae and other Lepidoptera related to communication with ants".Deinsea.4(1).Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2017.Retrieved6 November2017.

- ^Brakefield, P. M.; Kesbeke, F.; Koch, P. B. (December 1998). "The Regulation of Phenotypic Plasticity of Eyespots in the ButterflyBicyclus anynana".The American Naturalist.152(6): 853–60.doi:10.1086/286213.ISSN0003-0147.PMID18811432.S2CID22355327.

- ^Monteiro, A.; Pierce, N. E. (2001)."Phylogeny of Bicyclus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Inferred from COI, COII, and EF-1 Alpha Gene Sequences"(PDF).Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.18(2): 264–281.Bibcode:2001MolPE..18..264M.doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0872.PMID11161761.S2CID20314608.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 3 March 2019.

- ^Nijhout, Hf (January 2003). "Development and Evolution of Adaptive Polyphenisms".Evolution & Development.5(1): 9–18.doi:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2003.03003.x.ISSN1520-541X.PMID12492404.S2CID6027259.

- ^Brakefield, Paul M.; Larsen, Torben B. (1984)."The Evolutionary Significance of Dry and Wet Season Forms in some Tropical Butterflies"(PDF).Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.22:1–12.doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb00795.x.hdl:1887/11011.Archived(PDF)from the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved23 September2019.

- ^Lyytinen, A.; Brakefield, P. M.; Lindström, L.; Mappes, J. (2004)."Does Predation Maintain Eyespot Plasticity inBicyclus anynana".Proceedings of the Royal Society B.271(1536): 279–283.doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2571.PMC1691594.PMID15058439.

- ^"The Mathematical Butterfly: Simulations Provide New Insights On Flight".Inside Science.19 April 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 16 May 2018.Retrieved15 May2018.

- ^Meyer, A. (October 2006)."Repeating Patterns of Mimicry".PLOS Biology.4(10): e341.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040341.ISSN1544-9173.PMC1617347.PMID17048984.

- ^Science, 12 May 2017,"Where Have All the Insects Gone?"Archived8 March 2021 at theWayback MachineVol. 356, Issue 6338, pp. 576-579

- ^Reckhaus, Hans-Dietrich,"Why Every Fly Counts: A Documentation about the Value and Endangerment of Insects"Archived19 July 2021 at theWayback Machine(Springer International, 2017) pp.2-5

- ^Larsen, Torben (1994)."Butterflies of Egypt".Saudi Aramco World.45(5): 24–27.Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2010.Retrieved15 November2006.

- ^Haynes, Dawn.The Symbolism and Significance of the Butterfly in Ancient Egypt(PDF).

- ^Miller, Mary (1993).The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya.Thames & Hudson.ISBN978-0-500-27928-1.

- ^"Table Complete with Real Butterflies Embedded in Resin".Archived fromthe originalon 6 May 2010.Retrieved30 March2009.

- ^Pinar (13 November 2013)."Entire Alphabet Found on the Wing Patterns of Butterflies".Archivedfrom the original on 7 September 2015.Retrieved9 September2015.

- ^""The Butterfly that Stamped" | Just So Stories | Rudyard Kipling | Lit2Go ETC ".Archivedfrom the original on 8 August 2021.Retrieved8 August2021.

- ^Nilsson, Hans."Bellman på Spåren"(in Swedish). Bellman.net.Archivedfrom the original on 26 September 2015.Retrieved13 September2015.

- ^Van Rij, Jan (2001).Madame Butterfly: Japonisme, Puccini, and the Search for the Real Cho-Cho-San.Stone Bridge Press.ISBN9781880656525.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved8 January2016.

- ^Hearn, Lafcadio(1904).Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.Dover.ISBN978-0-486-21901-1.

- ^Louis, Chevalier de Jaucourt (Biography) (January 2011)."Butterfly".Encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert.Archivedfrom the original on 11 August 2016.Retrieved1 April2015.

- ^Hutchins, M., Arthur V. Evans, Rosser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003) Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Volume 3, Insects. Gale, 2003.

- ^Rabuzzi, M. 1997. Butterfly etymology. Cultural Entomology November 1997 Fourth issueonlineArchived3 December 1998 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Church Releases Butterflies as Symbol of Rebirth".The St. Augustine Record.Archivedfrom the original on 11 September 2015.Retrieved8 September2015.

- ^"I'm Scared to Be a Woman".Human Rights Watch. 24 September 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 6 September 2015.Retrieved8 September2015.

a 22-year-old transgender woman sports a tattoo of a butterfly—a transgender symbol signifying transformation

- ^Dorset Chronicle, May 1825, reprinted in:"The First Butterfly",inThe Every-day Book and Table Book; or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, Etc.Vol III, ed. William Hone, (London: 1838) p 678.

- ^"Superstitions and Beliefs Related to Death".Living in the Philippines.Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016.Retrieved9 October2015.

- ^"Official State Butterflies".NetState.Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2013.Retrieved9 September2015.

- ^Leach, William (27 March 2014)."Why Collecting Butterflies Isn't Cruel".Wall Street Journal.Archivedfrom the original on 13 February 2021.Retrieved17 January2021.

- ^"Collecting and Preserving Butterflies".Texas A&M UniversityBug Hunter.Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2020.Retrieved17 January2021.

- ^"Rearing caterpillars".Amateur Entomologists' Society(AES).Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2021.Retrieved17 January2021.

- ^Vukusic, Pete; Hooper, Ian (2005). "Directionally Controlled Fluorescence Emission in Butterflies".Science.310(5751): 1151.doi:10.1126/science.1116612.PMID16293753.S2CID43857104.

- ^Vanderbilt, Tom."How Biomimicry is Inspiring Human Innovation".Smithsonian.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2015.Retrieved8 September2015.

Further reading

- Kawahara, A.Y.; Storer, C.; Carvalho, A.P.S.; et al. (15 May 2023)."A Global Phylogeny of Butterflies Reveals Their Evolutionary History, Ancestral Hosts and Biogeographic Origins".Nat Ecol Evol.7(6): 903–913.Bibcode:2023NatEE...7..903K.doi:10.1038/s41559-023-02041-9.PMC10250192.PMID37188966.

External links

- Papilionoidea on the Tree of LifeArchived11 December 2008 at theWayback Machine

- Butterfly species and observations on iNaturalist

- Lamas, Gerardo (1990)."An Annotated List of Lepidopterological Journals"(PDF).Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera.29(1–2): 92–104.doi:10.5962/p.266621.S2CID108756448.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 August 2016.

- Rhopaloceraat insectoid.info

Regional lists

- North America

- Africa:GhanaArchived16 January 2021 at theWayback Machine

- Asia:SingaporeIsraelArchived22 October 2022 at theWayback MachineIndo-ChinaSulawesi(Southeastern Sulawesi)Turkey