Castro culture

Castro culture(Galician:cultura castrexa,Portuguese:cultura castreja,Asturian:cultura castriega,Spanish:cultura castreña,meaning "culture of the hillforts" ) is the archaeological term for thematerial cultureof the northwestern regions of theIberian Peninsula(present-day northern and centralPortugaltogether with theSpanishregions ofGalicia,Asturias,and westernLeón) from the end of theBronze Age(c. 9th century BC) until it was subsumed by Roman culture (c. 1st century BC). It is the culture associated with theGallaeciansandAstures.

The most notable characteristics of this culture are its walledoppidaandhillforts,known locally ascastros,from Latincastrum'castle', and the scarcity of visible burial practices, in spite of the frequent depositions of prestige items and goods, swords and other metallic riches in rocky outcrops, rivers and other aquatic contexts since theAtlantic Bronze Age.[1][2]This cultural area extended east to theCares riverand south into the lowerDouroriver valley.

The area ofAve Valleyin Portugal was the core region of this culture, with many small Castro settlements, but also including largeroppida,thecividades(from Latincivitas'city'), some known ascitâniasby archaeologists, due to their city-like structure: Cividade de Bagunte (Civitas Bogonti),Cividade de Terroso(Civitas Terroso),Citânia de Briteiros,and Citânia de Sanfins.[3]

History[edit]

The Castro culture emerged during the first two centuries of the first millennium BC, in the region extending from theDouroriver up to theMinho,but soon expanding north along the coast, and east following the river valleys,[4]reaching the mountain ranges which separate the Atlantic coast of the Iberian peninsula from the central plateau ormeseta.It was the result of the autonomous evolution of AtlanticBronze Agecommunities, after the local collapse of the long rangeAtlantic networkof interchange of prestige items.[5]

The end of the Atlantic Bronze Age[edit]

From theMondego riverup to theMinho river,along the coastal areas of northern Portugal, during the last two centuries of the second millennium BC a series of settlements were established in high, well communicated places,[6]radiating from a core area north of the Mondego, and usually specializing themselves in the production ofAtlantic Bronze Agemetallurgy:cauldrons,knives, bronze vases, roasting spits,flesh-hooks,swords, axes and jewelry relating to a noble elite who celebrated ritual banquets and who participated in an extensive network of interchange of prestige items, from theMediterraneanand up to theBritish Isles.These villages were closely related to the open settlements which characterized the first Bronze Age, frequently established near the valleys and the richer agricultural lands.

From the beginning of the first millennium, thenetwork appears to collapse,possibly because theIron Agehad outdated the Atlantic tin and bronze products in the Mediterranean region, and the large-scale production of metallic items was reduced to the elaboration of axes and tools, which are still found buried in very large quantities all along the European Atlantic coast.

Formative period[edit]

During the transition of the Bronze to the Iron Age, from theDouroin modern northern Portugal and up along the coasts of Galicia[7]until the central regions of Asturias, the settlement in artificially fortified places substituted the old open settlement model.[8]These earlyhill-fortswere small (1 ha at most), being situated in hills, peninsulas or another naturally defended places, usually endowed with long range visibility. The artificial defences were initially composed of earthen walls, battlements and ditches, which enclosed an inner habitable space. This space was mostly left void, non urbanised, and used for communal activities, comprising a few circular, oblong, or rounded squared huts, of 5 to 15 meters (16–49 ft) in the largest dimension,[9]built with wood, vegetable materials and mud, sometimes reinforced with stony low walls. The major inner feature of these multi-functional undivided cabins were thehearth,circular or quadrangular, and which conditioned the uses of the other spaces of the room.

In essence, the main characteristic of this formative period is the assumption by the community of a larger authority at the expense of the elites, reflected in the minor importance of prestige items production, while the collective invested important resources and labour in the communal spaces and defences.[10]

Second Iron Age[edit]

Since the beginning of the 6th century BC the Castro culture experienced an inner expansion: hundreds of new hill-forts were founded, while some older small ones were abandoned for new emplacements.[11]These new settlements were founded near valleys, in the vicinity of the richest farmlands, and these are generally protected by several defence lines, composed of ramparts, ditches, and sound stony walls, probably built not only as a defensive apparatus but also as a feature which could confer prestige to the community. Sometimes, human remains have been found incistsor under the walls, implying some kind of foundational protective ritual.[12]

Not only did the number of settlements grow during this period, but also their size and density. First, the old familiar huts were frequently substituted by groups of family housing, composed generally of one or more huts with hearth, plus round granaries, and elongated or square sheds and workshops. At the same time, these houses and groups tended to occupy most of the internal room of the hill-forts, reducing the communitarian open spaces, which in turn would have been substituted by other facilities such assaunas,[13]communitarian halls, and shared forges.

Although most of the communities of this period had self-sufficient isolated economies, one important change was the return of trade with the Mediterranean by the now independentCarthage,a thriving Western Mediterranean power. Carthaginian merchants brought imports of wine, glass, pottery and other goods through a series ofemporia,commercial posts which sometimes included temples and other installations. At the same time, the archaeological register shows, through the finding of large quantities offibulae,pins,pincersfor hair extraction,pendants,earrings,torcs,bracelets,and other personal objects, the ongoing importance of the individual and his or her physical appearance. While the archaeological record of the Castro Iron Age suggests a very egalitarian society, these findings imply the development of a privileged class with better access to prestige items.

| Oppida | |

|---|---|

| |

The oppida[edit]

From the 2nd century BC, specially in the south, some of the hill-forts turned into semi-urban fortified towns,oppida;[14]their remains are locally known ascividadesorcidades,cities, with populations of some few thousand inhabitants,[15]such as Cividade de Bagunte (50 ha), Briteiros (24 ha), Sanfins (15 ha), San Cibrao de Lás (20 ha), or Santa Tegra (15 ha); some of them were even larger than the cities, Bracara Augusti and Lucus Augusti, that Rome established a century later.

These native cities or citadels were characterised by their size and by urban features such as paved streets equipped with channels forstormwater runoff,reservoirs of potable water, and evidence of urban planning. Many of them also presented an inner and upper walled space, relatively large and scarcely urbanised, calledacrópoleby local scholars. These oppida were generally surrounded by concentric ditches and stone walls, up to five in Briteiros, sometimes reinforced with towers. Gates to these oppida become monumental and frequently have sculptures of warriors.

The oppida's dwelling areas are frequently externally walled, and kitchens, sheds, granaries, workshops and living rooms are ordered around an inner paved yard, sometimes equipped with fountains, drains and reservoirs.

Cividade de Bagunte (Norte Region) was one of the largest cities with 50 hectares. The cities are surrounded by a number of smaller castros, some of which may have been defensive outposts of cities, such as Castro de Laundos, that was probably an outpost of Cividade de Terroso. There is acividadetoponym inBraga,a citadel established by Augustus, although there are no archaeological findings apart from an ancient parish name and pre-Roman baths.Bracara Augustalater became the capital of the Roman province ofGallaecia,which encompassed all the lands once part of the Castro culture.

| Urbanism | |

|---|---|

| |

Roman era[edit]

The first meeting of Rome with the inhabitants of thecastrosandcividadeswas during the Punic wars, when Carthaginians hired local mercenaries for fighting Rome in the Mediterranean and into Italy.

Later on,GallaeciansbackedLusitaniansfighting Romans, and as a result the Roman generalDecimus Junius Brutus Callaicusled a successful punishment expedition into the North in 137 BC; the victory he celebrated in Rome granted him the title Callaicus ( “Galician” ). During the next centuryGallaeciawas still theatre of operation forPerpenna(73 BC),Julius Caesar(61 BC) and the generals ofAugustus(29-19 BC).[16]But only after the Romans defeated the Asturians and Cantabrians in 19 BC is evident—through inscriptions, numismatic and other archaeological findings—the submission of the local powers to Rome.

While the 1st century BC represents an era of expansion and maturity for the Castro Culture, under Roman influence and with the local economy apparently powered more than hindered by Roman commerce and wars, during the next century the control of Roma became political and military, and for the first time in more than a millennium new unfortified settlements were established in the plains and valleys, at the same time that numerous hill-forts and cities were abandoned. Strabo wrote, probably describing this process: "until they were stopped by the Romans, who humiliated them and reduced most of their cities to mere villages"(Strabo, III.3.5).

The culture went through somewhat of a transformation, as a result of the Roman conquest and formation of the Roman province ofGallaeciain the heart of the Castro cultural area; by the 2nd century AD most hill-forts and oppida had been abandoned or reused as sanctuaries or worshipping places, but some others kept being occupied up to the 5th century,[17]when the GermanicSueviestablished themselves in Gallaecia.

Economy and arts[edit]

As stated, whileBronze Ageeconomy was based on the exploitation and exportation of mineral local resources, tin and copper and on mass production and long range distribution of prestige items,Iron Ageeconomy was based on an economy of necessity goods,[18]as most items and productions were obtainedin situ,or interchanged thought short range commerce.

In the southern coastal areas the presence of Mediterranean merchants from the 6th century BC onward, would have occasioned an increase in social inequality, bringing many importations (finepottery,fibulae,wine,glassand other products) and technological innovations, such as roundgranitemillstones,which would have merged with the Atlantic local traditions.

Ancient Romanmilitary presence in the south and east of theIberian Peninsulasince the 2nd century BC would have reinforced the role of the autochthonous warrior elites, with better access to local prestige items and importations.

| Stonework | |

|---|---|

| |

Food and food production[edit]

Pollen analysisconfirms the Iron Age as a period of intense deforestation in Galicia and Northern Portugal, withmeadowsandfieldsexpanding at the expense ofwoodland.Using three main type of tools,ploughs,sicklesandhoes,together withaxesfor woodcutting, the Castro inhabitants grew a number of cereals: (wheat,millet,possibly alsorye) for baking bread, as well asoatsandbarleywhich they also used forbeerproduction.[19]They also grewbeans,peasandcabbage,andflaxfor fabric and clothes production; other vegetables were collected:nettle,watercress.Large quantities ofacornshave been found hoarded in mosthill-forts,as they were used for bread production once toasted and crushed in granite stone mills.[20]

The second pillar of local economy wasanimal husbandry.Gallaeciansbredcattlefor meat, milk and butter production; they also used oxen for dragging carts and ploughs,[21]whilehorseswere used mainly for human transportation. They also bredsheepandgoats,for meat and wool, andpigsfor meat. Wild animals likedeerorboarswere frequently chased. In coastal areas,fishingand collectingshellfishwere important activities:Strabowrote that the people of northern Iberia used boats made of leather, probably similar to Irishcurrachsand Welshcoracles,for local navigation.[22]Archaeologists have found hooks and weights fornets,as well as open seas fish remains, confirming inhabitants of the coastal areas as fishermen.[23]

Metallurgy[edit]

Mining was an integral part of the culture, and it attracted Mediterranean merchants, firstPhoenicians,laterCarthaginiansandRomans.Gold, iron, copper, tin and lead were the most common ores mined. Castrometallurgyrefined the metals from ores and cast them to make various tools.

During the initial centuries of the first millennium BC, bronze was still the most used metal, although iron was progressively introduced. The main products include tools (sickles, hoes, ploughs, axes), domestic items (knives and cauldrons), and weapons (antenna swords, spearheads). During the initial Iron Age, the local artisans stopped producing some of the most characteristic Bronze Age items such as carp tongue, leaf-shaped and rapierswords,double-ringed axes, breastplates and most jewellery.[24] From this time, the Castro culture develops jewellery of theHallstatttype, but with a distinctive Mediterranean influence, especially in the production of feminine jewellery.[25]Some 120 goldtorcsare known, produced in three main regional styles[26]frequently having large, void terminals, containing little stones which allowed them to be also used as rattles. Other metal artefacts includeantenna-hiltedswords and knives,Montefortino helmetswith local decoration and sacrificial or votive axes with depictions of complex sacrificial scenes (similar to classicalsuovetaurilia), with torcs, cauldrons, weapons, animals of diverse species and string-like motifs.[27]

Decorative motifs includerosettes,triskelions,swastikas,spirals,interlaces,as well as palm tree, herringbone and string motifs, many of which were still carved in Romanesque churches, and are still used today in local folk art and traditional items in Galicia, Portugal and northern Spain.[28][29]These same motifs were also extensively used in stone decoration. Castro sculpture also reveals that locals carved these figures in wood items, such as chairs, and wove them into their clothes.

| Metallurgy | |

|---|---|

| |

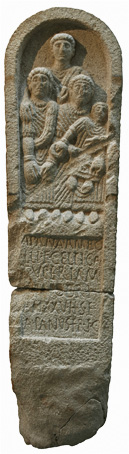

Stonework[edit]

While the use of stone for constructions is an old tradition in the Castro culture, dating from the 1st centuries of the 1st millennium BC, sculpture only became usual from the 2nd century BC, specially in the southern half of the territory, associated to the oppida. Five main types are produced, all of them in granite stone:[29]

- Guerreirosor 'Warrior statues', usually representing a male warrior in a standing pose, holding ready a short sword and acaetra(small local shield), and wearing a cap or helmet, torc,viriae(bracelets) and decorated shirt, skirt and belt.

- Sitting statues: They usually depicts what is considered to be a god sitting on a decorated throne, wearingviriaeor bracelets, and holding a cup or pot. Although the motives are autochthonous, their model are clearly Mediterranean; nevertheless, unlike the Gallaecian ones, the Iberian sitting statues usually depicts goddesses. Some few statues of feminine divinities are also known representing a standing nude woman only wearing a torc, as the male warrior statues.[30]

- Severed heads: similar to thetêtes coupéesfrom France;[31]they represent dead heads, and were usually located in walls of ancient hill-forts, and are still found reused near of them. Unlike all the other types, these are more common in the north.

- Pedras formosas(literally 'beauty stones'), or elaborated and sculpted slabs used insidesaunas,as door frame of the inner room.

- Architectural decoration: The houses of the oppida of southern Galicia and northernPortugalfrequently contains architectural elements engraved with geometric auspicious motives: rosettes, triskelions,wheels,spirals, swastikas, string like and interlaced designs, among others.[32]

| Pedra FormosaStonework | |

|---|---|

| |

Pottery and other crafts[edit]

Potterywas produced locally in a variety of styles, although wealthier people also possessed imported Mediterranean products. The richest pottery was produced in the south, from the Rias Baixas region in Galicia to theDouro,where decoration was frequently stamped and incised into pots and vases.[33]The patterns used often revealed the town where these were produced.

Language, society and religion[edit]

Society and government[edit]

In the 1st century AD, more than 700,000 people were living in the main area of the Castro culture, in hill forts and oppida.[34]NorthernGallaeci(Lucenses) were divided into 16populior tribes:Lemavi, Albiones, Cibarci, Egivarri Namarini, Adovi, Arroni, Arrotrebae, Celtici Neri, Celtici Supertamarci, Copori, Celtici Praestamarci, Cileni, Seurri, Baedui.Astureswere divided in Augustani and Transmontani, comprising 22 populi:Gigurri, Tiburi, Susarri, Paesici, Lancienses, Zoelae,among others. SouthernGallaecians(Bracareses), comprising the area of the oppida, were composed of 24civitates:Helleni, Grovi, Leuni, Surbi, Bracari, Interamnici, Limici, Querquerni, Coelerni, Tamagani, Bibali, Callaeci, Equasei, Caladuni...

Each populi or civitas was composed of a number ofcastella,each one comprehending one or more hill-forts or oppida, by themselves an autonomous political chiefdom, probably under the direction of a chief and a senate. Under Roman influence the tribes or populi apparently ascended to a major role, at the expense of the minor entities.[35]From the beginning of our era a few Latin inscriptions are known where some individuals declare themselvesprincepsorambimogidusof a certainpopuliorcivitas.

Onomastics and languages[edit]

The name of some of the castles and oppida are known through the declaration of origin of persons mentioned in epitaphs and votiveLatininscriptions[36](Berisamo, Letiobri, Ercoriobri, Louciocelo, Olca, Serante, Talabriga, Aviliobris, Meidunio, Durbede..), through the epithets of local Gods in votive altars (Alaniobrica, Berubrico, Aetiobrigo, Viriocelense...), and the testimony of classic authors and geographers (Adrobrica, Ebora, Abobrica, Nemetobriga, Brigantium, Olina, Caladunum, Tyde, Glandomirum, Ocelum...). Some more names can be inferred from modern place names, as those containing an evolution of the Celtic elementbrigsmeaning "hill" and characteristically ligated to old hill-forts[37][38](Tragove, O Grove < Ogrobre, Canzobre < Caranzobre, Cortobe, Lestrove, Landrove, Iñobre, Maiobre...) Approximately half the pre-Latin toponyms of Roman Gallaecia were Celtic, while the rest were either non Celtic western Indo-European, or mixed toponyms containing Celtic and non-Celtic elements.[39]

On the local personal names, less than two hundred are known,[40]many of which are also present either in the Lusitania, or either among the Astures, or among the Celtiberians. Whilst many of them have a sure Celtic etymology,[41][42]frequently related to war, fame or valour, others show preservation of /p/ and so are probably Lusitanian better than properly Celtic; in any case, many names could be Celtic or Lusitanian, or even belong to another indo-European local language. Among the most frequent names areReburrus,Camalus(related to Old Irishcam'battle, encounter'),Caturus(to Celtic *katu- 'fight'),Cloutius(to Celtic *klouto- 'renown', with the derivativesClutamus'Very Famous' andCloutaius,and the compositeVesuclotus'(He who have) Good Fame'),Medamus,Boutius,Lovesius,Pintamus,Ladronus,Apilus,Andamus(maybe to Celtic and-amo- 'The Undermost'),Bloena,Aebura/Ebura,Albura,Arius,CaeliusandCaelicus(to Celtic *kaylo-'omen'),Celtiatis,Talavius,Viriatus,among others.

A certain number of personal names are also exclusive to Gallaecia, among theseArtius(to Celtic *arktos 'bear'),NantiaandNantius(to Celtic *nant- 'fight'),Cambavius(to Celtic *kambo- 'bent'),Vecius(probably Celtic, fromPIE*weik- 'fight'),Cilurnius(to Celtic *kelfurn- 'cauldron'),Mebdius,Coralius(to PIE *koro- 'army'),Melgaecus(to PIE *hmelg-'milk'),Loveius,Durbidia,Lagius,Laucius,Aidius(to Celtic *aidu- 'fire'),Balcaius;and the compositesVerotius,Vesuclotus,Cadroiolo,Veroblius,among other composite and derivative names.

Very characteristic of the peoples of the Castro culture (Gallaecians and western Astures) is their onomastic formula. Whilst the onomastic formula among the Celtiberians usually is composed by a first name followed by a patronymic expressed as a genitive, and sometimes a reference to thegens,the Castro people complete name was composed as this:

- First Name + Patronymic (genitive) + [optional reference to thepopulior nation (nominative)] + 'castello' or its short form '>' + origin of the person = name of thecastro(ablative)

So, a name such as Caeleo Cadroiolonis F Cilenvs > Berisamo would stand forCailios son of Cadroyolo, a Cilenian, from the hill-fort named Berisamos.[43]Other similar anthroponymical patterns are known referring mostly to persons born in the regions in-between the rivers Navia in Asturias and Douro in Portugal, the ancient Gallaecia, among them:

- Nicer Clvtosi > Cariaca Principis Albionum:Nicer son of Clutosius, from (the hill-fort known as) Cariaca, prince of the Albions.

- Apana Ambolli F Celtica Supertam(arica)> [---]obri:Apana daughter of Ambollus, a Super-Tamaric Celtic, from (the hill-fort known as) [-]obri.

- Anceitvs Vacci F Limicvs > Talabric(a):Ancetos son of Vaccios, a Limic, from (the hill-fort known as) Talabriga.

- Bassvs Medami F Grovvs > Verio:Bassos son of Medamos, a Grovian, from (the hill-fort known as) Verio.

- Ladronu[s] Dovai Bra[ca]rus Castell[o] Durbede:Ladronos son of Dovaios, a Bracaran, from the castle Durbede.

Religion[edit]

| Religious objects | |

|---|---|

| |

The religious pantheon was extensive, and included local and pan-Celtic gods. Among the later ones the most relevant wasLugus;[44]5 inscriptions[45]are known with dedication to this deity, whose name is frequently expressed as a pluraldative(LUGUBO, LUCOUBU). The votive altars containing this dedications frequently present three holes for gifts or sacrifices. Other pan-European deities includeBormanicus(a god related to hot springs), theMatres,[46]andSulisorSuleviae(SULEIS NANTUGAICIS).[47]

More numerous are the votive inscriptions dedicated to the autochthonousCosus,Bandua,Nabia,andReue.Hundreds of Latin inscriptions have survived with dedications to gods and goddesses. Archaeological finds such as ceremonial axes decorated with animal sacrificial scenes, together with the severed head sculptures and the testimonies of classical authors, confirms the ceremonial sacrifice of animals,[48]and probably including human sacrifice as well, as among Gauls and Lusitanians.

The largest number of indigenous deities found in the whole Iberian Peninsula are located in theGalicianandLusitanianregions and models proposing a fragmented and disorganized pantheon have been discarded, since the number of deities occurring together is similar to other Celtic peoples in Europe and ancient civilizations.[citation needed][dubious–discuss]

Cosus,a male deity, was worshipped in the coastal areas where theCelticidwelt, from the region aroundAveiro,Portoand to Northern Galicia, but seldom inland, with the exception of theEl Bierzoregion in Leon, where this cult has been attributed[49]to the known arrival of Galician miners, most notably from among theCeltici Supertamarici.This deity has not been recorded in the same areas as Bandua, Reue and Nabia deities occur, and El Bierzo follows the same pattern as in the coast. From a theonymical point of view, this suggest some ethno-cultural differences between the coast and inland areas. With the exception of theGroviipeople,Pomponius Melastated that all thepopuliwere Celtic and Cosus was not worshipped there.Plinyalso rejected that the Grovii were Celtic, he considered them to have a Greek origin.

Bandua is closely associated with Roman Mars and less frequently worshipped by women. The religious nature of Cosus had many similarities with that of Bandua. Bandua had a warlike character and a defender of local communities. The worship of these two gods do not overlap but rather complement each other, occupying practically the whole of the western territory of the Iberian Peninsula. Supporting the idea, no evidence has been found of any women worshipping at any of the monuments dedicated to Cosus. Cosus sites are found near settlements, such as in Sanfins and the settlement near A Coruña, Galicia.

Nabia had double invocation, one male and one female. The supreme Nabia is related to Jupiter and another incarnation of the deity, identified with Diana, Juno or Victoria or others from the Roman pantheon, linked to the protection and defence of the community or health, wealth and fertility. Bandua, Reue,Arentius-Arentia,Quangeius,Munidis,Trebaruna,Laneana,andNabiaworshipped in the heart of Lusitania vanishes almost completely outside the boundary with theVettones.

Bandua,ReueandNabiawere worshipped in the core area ofLusitania(including NorthernExtremaduratoBeira Baixaand Northern Lusitania) and reaching inlandGalicia,the diffusion of these gods throughout the whole of the northern interior area shows a cultural continuity with Central Lusitania.

Funerary rites are mostly unknown except at few places, such asCividade de Terroso,wherecremationwas practised.

Major sites[edit]

World heritage candidates in 2010.

- Citânia de Briteiros,Guimarães,Northern Portugal

- Citânia de Sanfins,Paços de Ferreira,Northern Portugal

- Citânia de Santa Luzia,Viana do Castelo,Northern Portugal

- Citânia do Monte Mozinho,Penafiel,Northern Portugal

- Cividade de Terroso,Póvoa de Varzim,Northern Portugal

- Cividade de Bagunte,Vila do Conde,Northern Portugal

- Cividade de Âncora,CaminhaandViana do Castelo,Northern Portugal

- Santa Trega,A Guarda,Galicia

- San Cibrao de Las,Ourense,Galicia

- Castro de São Lourenço,Esposende,Northern Portugal

- Castro de Alvarelhos,Trofa,Northern Portugal

- Castro de Carmona,Barcelos,Northern Portugal

- Castro de Eiras,Vila Nova de Famalicão,Northern Portugal

- Castro de São Julião,Vila Verde,Northern Portugal

- Castromao,Ourense,Galicia

- Outeiro Lesenho,Boticas,Northern Portugal

- Outeiro Carvalhelhos,Boticas,Northern Portugal

- Outeiro do Pópulo,Alijó,Northern Portugal

- Outeiro de Romariz,Santa Maria da Feira,Northern Portugal

- Outeiro de Baiões,São Pedro do Sul,Northern Portugal

- Outeiro de Cárcoda,São Pedro do Sul,Northern Portugal

- Borneiro,Coruña,Galicia (Spain)

- Cabeço do Vouga,Águeda,Central Portugal

- Viladonga,Lugo,Galicia

-

Hill fort of Baroña,Porto do Son,Galicia

-

Detail ofCitâniade Sta. Luzia,Areosa,Norte Region

-

Baths or sauna atPunta dos Pradoshill-fort,Ortigueira,Galicia

-

Castro do Padrão,Santo Tirso,Norte Region

-

Citâniade Sanfins,Paços de Ferreira,Norte Region

-

A romanizedcastro,at Viladonga,Castro de Rei,Galicia

Other Castros in Asturias (Spain):

| Castro | Place | Dating | Comments |

| Arganticaeni | Piloña | ||

| Abándames | |||

| Almades, Les | Siero | ||

| Alto Castro | Somiedo | ||

| Atalaya de Tazones | Villaviciosa | ||

| Barrera, La | Carreño | ||

| Cabo Blanco, El | El Franco | Castro at sea | |

| Camoca | Villaviciosa | ||

| Canterona, La | Siero | ||

| Caravia | Caravia | ||

| Castelo, El | Boal | ||

| Castelo, El | Villanueva de Oscos | ||

| Castelón, El | Illano | ||

| Castello | Tapia | ||

| Castellois, Os | Illano | ||

| Castellón, El | El Franco | Castro at sea | |

| Castellón, El | El Franco | Castro at sea | |

| Castiello, El | Langreo | ||

| Castiello | Siero | Tiñana. | |

| Castiello, El | Cangas del Narcea | ||

| Castiello de la Marina | Villaviciosa | ||

| Castiellu de Ambás | Villaviciosa | ||

| Castro del Castiellu de Llagú | Oviedo | ||

| Castiellu de Lué | Villaviciosa | ||

| Castillos de Pereira | Tapia | ||

| Castrillón | Castrillón | Castro at sea | |

| Castrillón, El | Boal | ||

| Castro, El | Taramundi | Gold | |

| Castromior | San Martín de Oscos | ||

| Castromourán | Vegadeo | ||

| Castrón, El o de Arancedo | El Franco | ||

| Castros, Los | Tapia | ||

| Chao Sanmartín | Grandas de Salime | ||

| Coaña | Coaña | ||

| Cogollina, La | |||

| Cogolla, La | Oviedo | ||

| Corno, El | Castropol | Castro at sea | |

| Corona, La | El Franco | ||

| Corona, La | Ribera de Arriba | ||

| Corona, La | Somiedo | ||

| Corona del Castro, La | El Franco | ||

| Corona de Costru, La | Sobrescobio | ||

| Coronas, Las | Tapia | ||

| Cueto, El | Ribera de Arriba | ||

| Cueto, El | Siero | ||

| Cuitu, El | Siero | ||

| Curbiellu | Villaviciosa | ||

| Cuturulo o de Valabelleiro | Grandas de Salime | ||

| Deilán | San Martín de Oscos | ||

| Doña Palla | Pravia | ||

| Escrita, La | Boal | ||

| Espinaredo | Piloña | ||

| Esteiro, El | Tapia | ||

| Ferreira | Santa Eulalia de Oscos | ||

| Foncalada | Villaviciosa | ||

| Fuentes | Villaviciosa | ||

| Illaso | Villayón | Albion | |

| Lagar | Boal | ||

| Lineras | Santa Eulalia de Oscos | ||

| Mazos, Los | Boal | ||

| Medal | Coaña | Castro at Sea | |

| Meredo | Vegadeo | ||

| Miravalles | Villaviciosa | ||

| Mohías | Coaña | ||

| Molexón | Vegadeo | ||

| Montouto | Vegadeo | ||

| Morillón | Vegadeo | ||

| Muries, Les | Siero | ||

| Noega | Gijón | Castro at sea | |

| Obetao | Oviedo | ||

| Olivar | Villaviciosa | ||

| Ouria | Boal | ||

| Pedreres, Les | Ribera de Arriba | ||

| Pendia | Boal | ||

| Penzol | Vegadeo | ||

| Peña Castiello | Castrillón | ||

| Peña del Conchéu, La | Riosa | ||

| Picón, El | Tapia | ||

| Picu Castiellu | Langreo | ||

| Pico Castiello | Oviedo | ||

| Pico Castiello | Ribera de Arriba | ||

| Pico Castiello | Ribera de Arriba | ||

| Pico Castiello | Riosa | ||

| Pico Castiello, El | Siero | ||

| Picu Castiello, El | Siero | ||

| Picu Cervera | Belmonte de Miranda | ||

| Picu Castiellu de Moriyón | Villaviciosa | ||

| Picu da Mina, El | San Martín de Oscos | ||

| Pico El Cogollo | Oviedo | ||

| Piñera | Navia | in Peña Piñera at 1069 m | |

| Prahúa | Candamo | ||

| Punta de la Figueira, La | Castro at sea | ||

| Remonguila, La | Somiedo | ||

| Represas | Tapia de Casariego | ||

| Riera, La | Colunga | ||

| Salcido | San Tirso de Abres | ||

| San Ḷḷuis | Allande | Gold | |

| San Cruz | Pesoz | ||

| San Isidro | Pesoz | Gold | |

| San Pelayo | San Martín de Oscos | ||

| Sobia | Teverga | before 4th century BC | |

| Teifaros | Navia | Castro at sea. | |

| Torre, La | Siero | ||

| Trasdelcastro | Somiedo | ||

| Viladaelle | Vegadeo | ||

| Villarín del Piorno | San Martín de Oscos |

The Cariaca Castro is not identified, as only a small amount of Castros are called with his old names (like Coaña). Important Castros in the Albion Territory, near the Nicer stele and Navia and Eo Rivers are: Coaña, Chao de Samartín, Pendía and Taramundi.

See also[edit]

- List of castros in Galicia

- Celtic place-names in Galicia

- List of Celtic place names in Portugal

- Celts

- Gallaeci

- Galician Institute for Celtic Studies

- Gallaecian language

- Hispano-Celtic languages

Notes[edit]

- ^Rodríguez-Corral, J. (2009): 13.

- ^Comendador Rey, Beatriz."Space and Memory at the Mouth of the River Alla (Galicia, Spain)"(PDF).Conceptualising Space and Place: On the role of agency, memory and identity in the construction of space from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Iron Age in Europe.Archaeopress.Retrieved26 April2011.

- ^Armando Coelho Ferreira da SilvaA Cultura Castreja no Noroeste de PortugalMuseu Arqueológico da Citânia de Sanfins, 1986

- ^Rodríguez-Corral, J. (2009): 17-18.

- ^Rodríguez-Corral, J. (2009): 15.

- ^Rodríguez-Corral, J. (2009): 11.

- ^In 2006 a 9th-century BCE fortified factory for bronze production was discovered, and destroyed after being briefly studied, in Punta Langosteira, near modern dayA Coruña.Cf.http:// manuelgago.org/blog/index.php/2010/11/03/o-drama-historico-do-porto-exterior-da-coruna/

- ^Rodríguez-Corral, J. (2009): 17.

- ^Rodríguez-Corral, J. (2009): 21.

- ^Rodríguez-Corral, J. (2009): 14.

- ^This is the case ofNeixón Pequeno,abandoned after the construction of the nearbyNeixón Grandehill-fort (Rodríguez Corral, J 2009: 34)

- ^Rodríguez Corral, J 2009: 177-180.

- ^“Now some of the peoples that dwell next to the Durius River live, it is said, after the manner of the Laconians—using anointing-rooms twice a day and taking baths in vapours that rise from heated stones, bathing in cold water, and eating only one meal a day; and that in a cleanly and simple way.” (Strabo, III.3.3)

- ^The terms oppida and urbs are used by classical authors such as Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela for describing the major fortified town of NW Iberia.

- ^Rodríguez Corral (2009), p. 57

- ^Archaeologists have attributed to these expeditions and campaigns the partial destruction or abandonment of some of the largest oppida of northern Portugal (cf. Arias Vilas 1992: 18 and 23).

- ^(cf. Arias Vilas 1992: 67).

- ^González García, F. J., ed. (2007).Los pueblos de la Galicia céltica.akal. p. 275.ISBN978-84-460-2260-2.

- ^González García, F. J., ed. (2007).Los pueblos de la Galicia céltica.akal. p. 205.ISBN978-84-460-2260-2.

- ^”the mountaineers, for two-thirds of the year, eat acorns, which they have first dried and crushed, and then ground up and made into a bread that may be stored away for a long time.” (Strabo III.3.7)

- ^Rodriguez Corral 2009: 81.

- ^”Again, up to the time of Brutus they used boats of tanned leather on account of the flood-tides and the shoal-waters, but now, already, even the dug-out canoes are rare.” (Strabo, III.3.7.)

- ^Rodríguez Corral, Javier (2009).A Galicia castrexa.Lóstrego. p. 85.ISBN978-84-936613-3-5.

- ^González García, F. J. (2007). p. 261.

- ^' The Castro culture jewellery has its foundations in Hallstatt models, types and techniques. Hallstatt D, dated by means of its fibulae from 525 to 470 BC (...) contributed the techniques of stamping and inlaying, and items considered to be masculine: torcs, bracelets, diadems, and amulets. Over this basis worked a Mediterranean current, bringing filigree, granulate and new type of items considered to be feminine: earrings and collars.' ['A ourivería castrexa ten a súa base en modelos, tipos e decoracións hallstátticos. O Hallstatt D, datado polas fíbulas entre 525 e 470 a.C., (...) vai aportar a técnica do estampado e repuxado, e xoias, consideradas no Noroeste masculinas, como torques, brazaletes, diademas e amuletos. Sobre esta base vai actuar unha corrente mediterránea que traerá a filigrana e o granulado e novos tipos, quizais femininos, como as arracadas e os colares articulados'] Calo Lourido, F.A Cultura Castrexa.A nosa Terra. 1993.ISBN84-89138-71-0.p. 131.

- ^González Ruibal, Alfredo (2004) . p. 140-144.

- ^García Quintela (2005) pp. 529-530.

- ^cf. Romero, Bieito.Xeometrías Máxicas de Galicia.Ir Indo. 2009. ISBD 978-84-7680-639-5.

- ^abGonzález Ruibal, Alberto (2004).

- ^González Ruibal, Alberto (2004) pp. 123-124.

- ^González Ruibal, Alberto (2004) p. 135.

- ^González Ruibal, Alberto (2004) pp. 126-133.

- ^González Ruibal, Alberto (2004) p. 154-155.

- ^cf. Pliny the Elder. Natural History, III.27-28.

- ^González García, F. J. (2007), pp. 336-337.

- ^cf.Hispania Epigraphica on-line data-base.

- ^Prósper, B. M. (2002)Lenguas y religiones prerromanas del occidente de la península ibérica.Universidad de Salamanca. 2002.ISBN84-7800-818-7.pp. 374-380

- ^Koch, John T., ed. (2006).Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO. pp.790.ISBN1-85109-440-7.

- ^Curchin, Leonard A. (2008)."The Toponyms of the Roman Galicia: New Study".Cuadernos de Estudios Gallegos.LV(121): 109–136.Retrieved22 December2010.

- ^Cf. José María Vallejo Ruiz,Intentos de definición de un área antroponímica galaica,p. 227-262, inKremer, Dieter, ed. (2009).Onomástica galega II: onimia e onomástica prerromana e a situación lingüística do noroeste peninsular: actas do segundo coloquio, Leipzig, 17 3 18 de outubro de 2008.Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.ISBN978-84-9750-794-3.

- ^Cf. Luján Martinez (2006) p. 717-721.

- ^Cf. Zeidler, Jürgen (2007)Celto-Roman Contact Names in Galicia,p. 46-52, inKremer, Dieter, ed. (2007).Onomástica galega I.Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

- ^Cf. Juan Santos Yanguas,De nuevo sobre los Castella: naturaleza, territorio e integración en la Ciuitas,p. 169-183, inKremer, Dieter, ed. (2009).Onomástica galega II: onimia e onomástica prerromana e a situación lingüística do noroeste peninsular: actas do segundo coloquio, Leipzig, 17 3 18 de outubro de 2008.Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.ISBN978-84-9750-794-3.

- ^Olivares Pedreño (2002) p. 203-218.

- ^Brañas Abad, Rosa.Entre mitos, ritos y santuarios. Los dioses Galaico-Lusitanos.p. 402, in González García (2007).

- ^Marco Simon, F. (2005) p. 302-303.

- ^Luján Martínez (2006) p. 722.

- ^Armada, Xosé-Lois; García-Vuelta, Óscar."Os atributos do guerreiro, as ofrendas da comunidade. A interpretación dos torques a través da iconografía".CÁTEDRA. Revista eumesa de estudios.Retrieved16 July2015.

- ^Olivares Pedreño, Juan Carlos (2007)."Hipótesis Sobre El Culto Al Dios Cossue En El Bierzo (León): Explotaciones Mineras y Migraciones"(PDF).Paleohispanistica.7:143–160.Retrieved2 May2012.

Bibliography[edit]

- Arias Vila, F. (1992).A Romanización de Galicia.A Nosa Terra. 1992.ISBN84-604-3279-3.

- Armada, Xosé-Lois; García-Vuelta, Óscar."Os atributos do guerreiro, as ofrendas da comunidade. A interpretación dos torques a través da iconografía".CÁTEDRA. Revista eumesa de estudios.Retrieved16 July2015.

- Ayán Vila, Xurxo (2008).A Round Iron Age: The Circular House in the Hillforts of the Northwestern Iberian PeninsulaArchived2011-06-24 at theWayback Machine.In e-Keltoi, Volume 6: 903-1003. UW System Board of Regents, 2008. ISSN 1540-4889.

- Calo Lourido, F. (1993).A Cultura Castrexa.A nosa Terra. 1993.ISBN84-89138-71-0.

- García Quintela (2005).Celtic Elements in Northwestern Spain in Pre-Roman timesArchived2015-01-31 at theWayback Machine.In e-Keltoi, Volume 6: 497-569. UW System Board of Regents, 2005. ISSN 1540-4889.

- González García, F. J. (ed.) (2007). Los pueblos de la Galicia céltica. AKAL. 2007.ISBN978-84-460-2260-2.

- González Ruibal, Alfredo (2004).Artistic Expression and Material Culture in Celtic Gallaecia'Archived2015-01-22 at theWayback Machine.In e-Keltoi, Volume 6: 113-166. UW System Board of Regents, 2004. ISSN 1540-4889.

- Júdice Gamito, Teresa (2005).The Celts in PortugalArchived2012-10-08 at theWayback Machine.In e-Keltoi, Volume 6: 571-605. UW System Board of Regents, 2005. ISSN 1540-4889.

- Luján Martínez, Eugenio R. (2006)The Language(s) of the Callaeci[permanent dead link].In e-Keltoi, Volume 6: 715-748. UW System Board of Regents, 2005. ISSN 1540-4889.

- Marco Simón, Francisco (2005).Religion and Religious Practices of the Ancient Celts of the Iberian Peninsula.In e-Keltoi, Volume 6: 287-345. UW System Board of Regents, 2005. ISSN 1540-4889.

- Olivares Pedreño, Juan Carlos (2002).Los dioses de la Hispania celtica.Madrid: Universitat de Alacant.ISBN9788495983008.

- Parcero-Oubiña C. and Cobas-Fernández, I (2004).Iron Age Archaeology of the Northwest Iberian Peninsula.In e-Keltoi, Volume 6: 1-72. UW System Board of Regents, 2004. ISSN 1540-4889.

- Prósper, B. M. (2002)Lénguas y religiones prerromanas del occidente de la península ibérica.Universidad de Salamanca. 2002.ISBN84-7800-818-7.

- Rodríguez-Corral, Javier (2009).A Galicia Castrexa.Lóstrego. 2009.ISBN978-84-936613-3-5.

- Romero, Bieito (2009).Xeometrías Máxicas de Galicia.Ir Indo. 2009.ISBN978-84-7680-639-5.

- Silva, A. J. M. (2012),Vivre au-delà du fleuve de l'Oubli. Portrait de la communauté villageoise du Castro do Vieito au moment de l'intégration du NO de la péninsule ibérique dans l'orbis Romanum (estuaire du Rio Lima, NO du Portugal)(in French), Oxford, United Kingdom: Archaeopress

External links[edit]

- Silva, A. J. M. (2009),Vivre au déla du fleuve de l'Oubli. Portrait de la communauté villageoise du Castro do Vieito, au moment de l'intégration du NO de la péninsule ibérique dans l'orbis romanum (estuaire du Rio Lima, NO du Portugal),Phd Thesis presented at Coimbra University in March 2009, 188p.PDF version.

- Castro culture

- Celtic archaeological cultures

- Iron Age cultures of Europe

- Archaeological cultures of Europe

- Archaeological cultures in Portugal

- Iron Age Portugal

- Archaeological cultures in Spain

- History of Galicia (Spain)

- Culture of Galicia

- History of Asturias

- History of Cantabria

- Castile and León

- Prehistory of the Basque Country

- 9th-century BC establishments

- 1st-century BC disestablishments