Arnold Wesker

Sir Arnold Wesker | |

|---|---|

Wesker at the Durham Book Festival in 2008 | |

| Born | 24 May 1932 Stepney,London, England |

| Died | 12 April 2016(aged 83)[1] Brighton,England |

| Occupation | Dramatist |

| Notable awards | Knight Bachelor(2006) |

| Website | |

| arnoldwesker | |

Sir Arnold WeskerFRSL(24 May 1932 – 12 April 2016) was anEnglish dramatist.He was the author of 50 plays, four volumes of short stories, two volumes of essays, much journalism and a book on the subject, a children's book, some poetry, and other assorted writings. His plays have been translated into 20 languages, and performed worldwide.

Early life

[edit]Wesker was born inStepney,London, in 1932,[2]the son of Leah (née Cecile Leah Perlmutter), a cook, and Joseph Wesker, a tailor's machinist and active communist.[3]

Arnold Wesker was delivered by Samuel Sacks, father of neurologistOliver Sacks.[4]

He attended a Jewish Infants School inWhitechapel.His education was then fragmented duringWorld War II.He was brieflyevacuatedtoEly,Cambridgeshire,before returning to London where he attended Dean Street School duringthe Blitz.He then returned to live with his parents who had moved to a council flat inHackney,East London, where he attended Northwold Road School. He then attended Upton House Central School, Hackney, from 1943. This was a school where emphasis was placed on teaching office skills, including typing, to bright boys who however had not been selected forgrammar schoolplaces. He was then evacuated again toLlantrisant,South Wales.[5]

He was accepted into theRoyal Academy of Dramatic Artbut could not afford to take up his place there. Later, he served for two years in theRoyal Air Force,and then went on to work as cook, furniture maker, and bookseller.[6]

After saving up enough money, he went to study at the London School of Film Technique, now known as theLondon Film School[7]

Career

[edit]His inspiration for the 1957 playThe Kitchen,which waslater made into a film,came when he was working at theBell HotelinNorwich.[8]It was while working here that he met his future wife Dusty.

Wesker's plays have dealt with themes including self-discovery, love, confronting death and political disillusion.Chicken Soup with Barley(1958) went out to the regions. Rather than opening in theWest End,its premiere was seen at theCoventry Theatre,a locale which typified Wesker's political views as an 'angry young man'.

Wesker's playRoots(1959) was akitchen sink dramaabout a girl, Beatie Bryant, who returns after three years of stay in London to her farming family home in Norfolk and struggles to voice herself.[9]Critics commended the "emotional authenticity" brought out in the play.[10]Roots,The Kitchen,andTheir Very Own and Golden Citywere staged by the English Stage Company at theRoyal Court Theatreunder the management ofGeorge Devineand laterWilliam Gaskill. Wesker's 1962 play "Chips With Everything" shows class attitudes at the time by examining the life of an Army corporal.

Nuclear disarmament

[edit]Wesker joined with enthusiasm the Royal Court group on theAldermaston Marchin 1959. Another of the Royal Court contingent,Lindsay Anderson,made a short documentary film (March to Aldermaston) about the event. He was an active member of theCommittee of 100and, with other prominent members, was jailed in 1961 for his part in its campaign of mass nonviolent resistance to nuclear weapons.[11]

Centre 42

[edit]After his stay in prison in 1961, Wesker made a full-time commitment to become the leader of an initiative which arose from Resolution 42 of the 1960Trades Union Congress,concerning the importance of arts in the community. Centre 42 was initially a touring festival aimed at devolving art and culture from London to the other main working class towns of Britain, moving to theRoundhousein 1964. The project to establish a permanent arts centre struggled through subsequent years, because its funding was limited; Wesker fictionalised it in his playTheir Very Own and Golden City(1966). He formally dissolved the project in 1970, although The Roundhouse did eventually open as a permanent arts centre in 2006.[12]

Writers & Readers Publishing Cooperative

[edit]Wesker co-founded, in 1974,[13]theWriters & Readers Publishing Cooperative Ltd,with a group of writers that includedJohn Berger,Lisa Appignanesi,Richard Appignanesi,Chris SearleandGlenn Thompson.

Later works

[edit]The Journalists(1972) was commissioned by theRoyal Shakespeare Companyand researched atThe Sunday Timesat a time it when was edited byHarold Evans.The RSC's literary manager Ronald Bryden thought it would be "the play of the decade" and it was scheduled to be directed byDavid Jones.[14]The actors in that year's RSC company refused to perform it, Wesker said, because they were under the influence of theWorkers Revolutionary Party.[15](The WRP was not founded until 1973, but its forerunner, the Socialist Labour League had many sympathisers in the RSC.)[14]Wesker wrote in 2004 that he had also "committed the politically incorrect crime of creating Tory ministers who were intelligent rather than caricatures".[15]

The Journalistsreceived its American premiere at theBack Alley Theatrein Los Angeles in 1979. It was directed by Laura Zucker and produced byAllan Miller.

Wesker's playThe Merchant(1976), which he later renamedShylock,uses the same three stories used by Shakespeare for his playThe Merchant of Venice.

In this retelling, Shylock and Antonio are fast friends bound by a common love of books, culture and a disdain for the crass antisemitism of the Christian community's laws. They make the bond in defiant mockery of the Christian establishment, never anticipating that the bond might become forfeit. When it does, the play argues, Shylock must carry through on the letter of the law or jeopardise the scant legal security of the entire Jewish community. He is, therefore, quite as grateful as Antonio when Portia, as in Shakespeare's play, shows the legal way out.

The play received its American premiere on 16 November 1977 at New York's Plymouth Theatre withJoseph Leonas Shylock,Marian Seldesas Shylock's sister Rivka andRoberta Maxwellas Portia. This production had a challenging history in previews on the road, culminating (after the first night out of town in Philadelphia on 8 September 1977) with the death of the exuberant Broadway starZero Mostel,who was initially cast as Shylock.

Wesker wrote a book,The Birth of Shylock and the Death of Zero Mostel,chronicling the entire process from initial submissions and rejections of the play through to rehearsals, Zero's death, and the disappointment of the critical reception for the Broadway opening. The book reveals much about the playwright's relationship to directorJohn Dexter(who had been the earliest, near-familial interpreter of Wesker's works), to criticism, to casting, and to the ephemeral process of collaboration through which the text of any play must pass.[16]

In 2005, he published his first novel,Honey,which recounted the experiences of Beatie Bryant, the heroine of his earlier playRoots.The novel broke from the previously established chronology.Rootswas set in the early 1960s and Beatie is 22; but inHoneyshe has only aged three years yet the action has been transplanted into the 1980s. Other oddities are that the timeframe includes theRushdie affairandJohn Major's fall as recent events and yet the action is concerned with thedotcom boom.[17]

In 2008, Wesker published his first collection of poetry,All Things Tire of Themselves(Flambard Press). The collection dates back many years and represents what he considered his best and most characteristic poems. He was a member of the editorial advisory board ofJewish Renaissancemagazine.[18]

He was a patron of theShakespeare Schools Festival,a charity that enables school children across the UK to perform Shakespeare in professional theatres.[19]

He was the castaway onDesert Island Discs,BBC Radio 4,in 1966 and again in 2006.[20]

Archive

[edit]Wesker's papers, covering his entire career, were acquired by theHarry Ransom Centerat theUniversity of Texas at Austinin 2000. The collection contains not only the prolific output of the playwright, novelist and poet but also is framed within the larger historical context of international events. Wesker was actively involved in the organizing of his archive, and before shipping it to the Ransom Center, Wesker compiled a list of the contents, which is also available to scholars for consultation. The collection's contents include over three hundred boxes of manuscript drafts, correspondence, production ephemera, personal records, and other materials.[21]Wesker's family shipped the last of his papers to the Ransom Center in March, 2016 shortly before his death.

On 13 April 2016, the Leader of the Opposition,Jeremy Corbyn,gave thanks for the playwright's life. They shared a socialist background in London, where Corbyn is an MP.

I am sure the whole House will join me in mourning the death of the dramatist Arnold Wesker, one of the great playwrights of this country, one of those wonderful angry young men of the 1950s who, like so many angry young people, changed the face of our country.[22]

The BBC repeated in May 2016 the retrospective radio programme on Wesker's career first broadcast on his 80th birthday.[23]

Personal life

[edit]"And though, like most writers, I fear dying before I write that one masterpiece for which I'll be remembered, yet I look at the long row of published work that I keep before me on my desk and I think, not bad, Wesker, not bad."

– Wesker on his 70th birthday[24]

Wesker married Doreen Bicker in 1958, after meeting at a hotel in Norwich where Wesker was working as a kitchen porter and Doreen as a chambermaid. He gave her the nickname of "Dusty", because of her "gold-dust" hair; anArts Councilbursary of £500 covered the cost of their marriage.[1]The character Beatie, in the "Wesker trilogy" of plays, was inspired by her. The couple had three children: Lindsay, Tanya and Daniel. Lindsay was named after directorLindsay Anderson.Tanya died in 2012. Wesker also had another daughter Elsa, with Swedish journalist, Disa Håstad.[1]

Wesker died on 12 April 2016 at theRoyal Sussex County Hospitalin Brighton.[25]He was suffering fromParkinson's disease.[26]

Awards and honours

[edit]

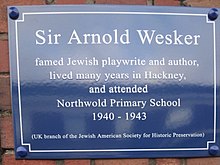

Wesker received numerous awards throughout his career. In 1958 he received grant of£300 for the playChicken Soupfrom theArts Council of Great Britain.[27]He used the money to marry Bicker.[6]The following year he won theEvening StandardTheatre Awardin the "Most Promising Playwright" category.[28]He was presented with the ItalianMarzotto Prize(a cash award of £3000) in 1964 forTheir Very Own and Golden City,and the Spanish Best Foreign Play Award in 1979. He became a fellow of theRoyal Society of Literaturein 1985 and was presented with theGoldie Awardin 1987. For his "distinguished service to theatre" he was honoured with theLast Frontier Lifetime Achievement Awardin 1999.[27]He wasknightedin the2006 New Year Honours.[1]In December 2021 a plaque in Wesker's memory was installed at his former primary school, Northwold Road, Hackney, London, by theJewish American Society for Historic Preservation.[29][30]

Works

[edit]The following list is drawn from Arnold Wesker's official website.[31]

Plays

[edit]- The Kitchen,1957ISBN978-1-84943-757-8

- Chicken Soup with Barley,1958ISBN978-1-4081-5661-2

- Roots,1959ISBN978-1-4725-7461-9

- I'm Talking about Jerusalem,1960

- Menace,1961 (for television)

- Chips with Everything,1962

- The Nottingham Captain,1962

- Four Seasons,1965

- Their Very Own and Golden City,1966

- The Friends,1970

- The Old Ones,1970

- The Journalists,1972ISBN0-14-048133-8

- The Wedding Feast,1974

- The Merchant,1976

- Love Letters on Blue Paper,1976

- One More Ride On The Merry-Go-Round,1978

- Phoenix,1980

- Caritas,1980ISBN978-0-224-02020-6

- Voices on the Wind,1980

- Breakfast,1981

- Sullied Hand,1981

- Four Portraits – Of Mothers,1982

- Annie Wobbler,1982

- Yardsale,1983

- Cinders,1983

- Whatever Happened to Betty Lemon?,1986

- When God Wanted a Son,1986

- Lady Othello,1987

- Little Old Lady & Shoeshine,1987

- Badenheim 1939,1987

- Shoeshine,1987

- The Mistress,1988

- Beorhtel's Hill,1988 (community play forBasildon)

- Men Die Women Survive,1990

- Letter To A Daughter,1990

- Blood Libel,1991

- Wild Spring,1992

- Bluey,1993

- The Confession,1993

- Circles of Perception,1996

- Break, My Heart,1997

- Denial,1997

- Barabbas,2000

- The Kitchen Musical,2000

- Groupie,2001ISBN1-84943-741-6

- Longitude,2002

- The Rocking Horse,2008 (commissioned by theBBCWorld Service)

- Joy and Tyranny,2011ISBN978-1-84943-546-8

Fiction

[edit]- Six Sundays in January,Jonathan Cape,1971

- Love Letters on Blue Paper,Jonathan Cape, 1974

- Said the Old Man to the Young Man,Jonathan Cape, 1978

- Fatlips,Writers and ReadersHarper & Row,1978

- The King's Daughters,Quartet Books,1998

- Honey,Pocket Books,2006

Non-fiction

[edit]- Distinctions,1985 (collection of essays)

- Fears of Fragmentation,Jonathan Cape, 1971

- Say Goodbye You May Never See Them Again,Jonathan Cape, 1974

- Journey Into Journalism,Writers & Readers, 1977

- The Dusty Wesker Cook Book,Chatto & Windus, 1987

- As Much as I Dare,Century Random House, 1994 (Autobiography)

- The Birth of Shylock and the Death of Zero Mostel,Quartet Books, 1997

- Wesker On Theatre,2010 (collection of essays)ISBN978-1-84943-376-1

- Ambivalences,Oberon Books, 2011

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcdPascal, Julia (13 April 2016)."Sir Arnold Wesker obituary".The Guardian.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^"Birthday's today".The Telegraph.24 May 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 24 May 2013.Retrieved24 May2014.

Sir Arnold Wesker, playwright, 81

- ^"Arnold Wesker Biography (1932-)".Filmreference.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^Bernard Jacobson (2015).Star Turns and Cameo Appearances: Memoirs of a Life Among Musicians.Boydell & Brewer. p. 167.ISBN978-1-58046-541-0.

- ^An education in the life of Arnold Wesker atThe IndependentRetrieved 13 April 2016

- ^abReade W. Dornan (2014).Arnold Wesker: A Casebook.Routledge.ISBN978-1-135-54145-3.

- ^"Sir Arnold West Obituary ".Guardian.12 April 2016.Retrieved4 June2020.

- ^"Twentieth Century English Literature - Arnold Weskers: Roots".Vidya-mitra. 13 December 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2021.Retrieved8 February2019.

- ^Lyn Gardner (9 October 2013)."Roots – Review".The Guardian.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^Dan Rebellato (2002).1956 and All That: The Making of Modern British Drama.Routledge. p. 101.ISBN978-1-134-65783-4.

- ^"Sir Arnold Wesker, British playwright, dies aged 83".BBC.13 April 2016.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^Clive Barker (1 May 2014)."Vision and Reality - 'Their Very Own and Golden City' and Centre 42".In Dornan, Reade W. (ed.).Arnold Wesker: A Casebook.Routledge. pp. 89–96.ISBN9781135541453.Retrieved4 February2018.

- ^"Libros para Principiantes: Quienes somos".Paraprincipiantes.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^abSweet, Matthew (16 May 2012)."Arnold Wesker: Did Trotskyists kill off the best Seventies play?".The Daily Telegraph.Retrieved25 March2020.

- ^abWesker, Arnold (19 July 2004)."Diary - Arnold Wesker".New Statesman.Retrieved25 March2020.

- ^Selected works[permanent dead link]

- ^Alfred Hickling (8 October 2005)."Review: Honey – Back to his Roots".The Guardian.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^"Who We Are".Jewish Renaissance.Archived fromthe originalon 10 October 2012.Retrieved21 November2012.

- ^"Shakespeare Schools Foundation Patrons".Shakespeare Schools Foundation.Shakespeare Schools Foundation.Archived fromthe originalon 11 December 2017.Retrieved12 July2021.

- ^Symons, Mitchell (2012).Desert Island Discs: Flotsam & Jetsam: Fascinating facts, figures and miscellany from one of BBC Radio 4's best-loved programmes.Random House.p. 24.ISBN978-1-4481-2744-3.

- ^"Arnold Wesker: A Preliminary Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center".norman.hrc.utexas.edu.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^"Engagements - Hansard Online".Archived fromthe originalon 12 May 2016.Retrieved24 April2016.

- ^"Arnold Wesker, Sunday Feature - BBC Radio 3".

- ^"Playwright Sir Arnold Wesker dies, aged 83".

- ^Baker, William (9 January 2020). "Wesker, Sir Arnold (1932–2016), playwright".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.111654.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^Quinn, Ben."British playwright Arnold Wesker dies, aged 83".The Guardian.Retrieved12 April2016.

- ^abSorrel Kerbel (2004).The Routledge Encyclopedia of Jewish Writers of the Twentieth Century.Routledge.p. 1146.ISBN978-1-135-45607-8.

- ^"Sir Arnold Wesker".British Council.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^"Blue Plaque of Sir Arnold Wesker Underscores Jewish Contributions to British Life".3 January 2022.

- ^"Plaque honouring dramatist Sir Arnold Wesker unveiled at his former school".

- ^"Arnold Wesker – Work".Arnold Wesker. Archived fromthe originalon 29 July 2018.Retrieved13 April2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Ambivalences,Oberon Books, 2011ISBN1-84943-334-8

- Chambers Biographical Dictionary(Chambers, Edinburgh, 2002)ISBN0-550-10051-2

- The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(Oxford 2004)

- De Ornellas, Kevin (2005). David Malcolm (ed.)."British and Irish short-fiction writers, 1945-2000".Dictionary of Literary Biography.319.ISBN978-0787681371.

- De Ornellas,Kevin. Focus on 'The Wesker Trilogy',Greenwich Exchange Press, 2020.ISBN978-1-910996-41-6

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Arnold Wesker Papersat theHarry Ransom Center,University of Texas at Austin

- Arnold WeskeratIMDb

- "Arnold's Choice".Interview with Arnold Wesker, byKirsty Young.Desert Island Discs.Broadcast onBBC Radio 4,17 December 2006; repeated 22 December 2006.

- Interview with Arnold Wesker– British Library sound recording

- "Sir Arnold Wesker, British playwright, dies aged 83",BBC News, 13 April 2016

- Chris, Moncrieff,"Obituary: Sir Arnold Wesker, playwright",The Scotsman,13 April 2016

- Archival material at

- "ir Arnold Wesker",The Royal Society of Literature

- 1932 births

- 2016 deaths

- 20th-century English dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century English dramatists and playwrights

- English male dramatists and playwrights

- Jewish dramatists and playwrights

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Knights Bachelor

- People educated at University College School

- People from Stepney

- English Jews

- People with Parkinson's disease

- 20th-century English male writers

- 21st-century English male writers

- Alumni of the London Film School