Champagne wine region

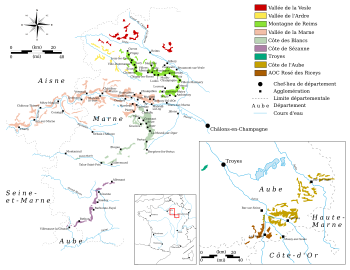

Thewine regionwithin thehistorical province of Champagnein the northeast ofFranceis best known for the production ofchampagne,the sparkling white wine that bears the region's name. EU law and the laws of most countries reserve the term "champagne" exclusively for wines that come from this region located about 160 kilometres (100 miles) east ofParis.Theviticulturalboundaries of Champagne are legally defined and split into five wine-producing districts within the historical province:Aube,Côte des Blancs,Côte de Sézanne,Montagne de Reims,andVallée de la Marne.The city ofReimsand the town ofÉpernayare the commercial centers of the area. Reims is famous for its cathedral, the venue of the coronation of the French kings and a UNESCOWorld Heritage Site.[1]

Located at the northern edges of France, the history of the Champagne wine region has had a significant role in the development of this uniqueterroir.The area's proximity to Paris promoted the region's economic success in its wine trade but also put the villages and vineyards in the path of marching armies on their way to the French capital. Despite the frequency of these military conflicts, the region developed a reputation for quality wine production in the early Middle Ages and was able to continue that reputation as the region's producers began making sparkling wine with the advent of the great champagne houses in the 17th and 18th centuries. The principal grapes grown in the region includeChardonnay,Pinot noir,andPinot Meunier.Pinot noir is the most widely planted grape in the Aube region and grows very well in Montagne de Reims. Pinot Meunier is the dominant grape in the Vallée de la Marne region. The Côte des Blancs is dedicated almost exclusively to Chardonnay.[2]

The unique, chalky landscape of the Champagne wine region and the resulting agro-industrial system led to the development of sparkling wines like champagne in the 17th century. As a result, many of the production sites and wine houses in the region were inscribed on theUNESCOWorld Heritage Listin 2015 as part theChampagne hillsides, houses and cellarssite.[3]

Geography and climate

[edit]

The Champagne province is located near the northern limits of the wine world along the49th parallel.The high latitude and mean annual temperature of 10 °C (50 °F) creates a difficult environment for wine grapes to fully ripen. Ripening is aided by the presence offorestswhich helps to stabilize temperatures and maintain moisture in the soil. The cool temperatures serve to produce high levels ofacidityin the resulting grape which is ideal forsparkling wine.[4]

During the growing season, themeanJuly temperature is 18 °C (66 °F). The average annual rainfall is 630 mm (25 inches), with 45 mm (1.8 inches) falling during theharvestmonth of September. Throughout the year, growers must be mindful of the hazards of fungal disease and early spring frost.[5]

Ancient oceans left behindchalksubsoil deposits when they receded 70 million years ago.Earthquakesthat rocked the region over 10 million years ago pushed the marine sediments of belemnite fossils up to the surface to create the belemnite chalk terrain. The belemnite in the soil allows it to absorb heat from the sun and gradually release it during the night as well as providing good drainage. This soil contributes to the lightness and finesse that is characteristic of Champagne wine. The Aube area is an exception with predominatelyclaybased soil.[4]The chalk is also used in the construction of underground cellars that can keep the wines cool through the bottle maturation process.[5]

History

[edit]

TheCarolingianreign saw periods of prosperity for the Champagne region beginning withCharlemagne's encouragement for the area to start planting vines and continuing with the coronation of his sonLouis the Piousat Reims. The tradition of crowning kings at Reims contributed to the reputation of the wines that came from this area.[6]TheCounts of Champagneruled the area as an independent county from 950 to 1316. In 1314, the last Count of Champagne assumed the throne as KingLouis X of Franceand the region became part of the Crown territories.

Military conflicts

[edit]The location of Champagne played a large role in its historical prominence as it served as a "crossroads" for both military and trade routes. This also made the area open to devastation and destruction during military conflicts that were frequently waged in the area. In 451 A.D. nearChâlons-en-Champagne,Attilaand theHunswere defeated by an alliance ofRoman legions,FranksandVisigoths.This defeat was a turning point in the Huns' invasion of Europe.[7]

During theHundred Years' War,the land was repeatedly ravaged and devastated by battles. The Abbey ofHautvillers,including its vineyards, was destroyed in 1560 during theWar of Religionbetween theHuguenotsandCatholics.This was followed by conflicts during theThirty Year Warand theFrondeCivil War where soldiers andmercenariesheld the area in occupation. It was not until the 1660s, during the reign ofLouis XIV,that the region saw enough peace to allow advances in sparkling wine production to take place.[8]

History of wine production

[edit]

The region's reputation for wine production dates back to theMiddle Ageswhen PopeUrban II( ruled 1088-1099 AD/CE ), a native Champenois, declared that the wine ofAÿin the Marne département was the best wine produced in the world. For a timeAÿwas used as ashorthanddesignation for wines from the entire Champagne region, similar to the use ofBeaunefor the wines ofBurgundy.[9]The poetHenry d'Andeli's workLa Bataille des Vinsrated wines from the towns of Épernay,Hautvillersand Reims as some of the best in Europe. As the region's reputation grew, popes and royalty sought to own pieces of the land with PopeLeo X,Francis I of France,Charles V of Spain,andHenry VIII of Englandall owning vineyard land in the region. A batch of wine from Aÿ received in 1518 by Henry VIII's chancellor,CardinalThomas Wolsey,is the first recorded export of wine from the Champagne region to England.[10]

The still wines of the area were highly prized in Paris under the designation ofvins de la rivièreandvins de la montagne- wines of the river and wines of the mountain in reference to the wooded terrain and the riverMarnewhich carried the wines down to theSeineand into Paris.[11]The region was in competition with Burgundy for theFlemishwine trade and tried to capitalize on Reims' location along the trade route from Beaune. In the 15th century,Pinot noirbecame heavily planted in the area. The resulting red wine had difficulty comparing well to the richness and coloring ofBurgundy wines,despite the addition ofelderberriesto deepen the color. This led to a greater focus on white wines.[12]

The Champagne house ofGossetwas founded as a still wine producer in 1584 and is the oldestChampagne housestill in operation today.Ruinartwas founded in 1729 and was soon followed byChanoine Frères(1730),Taittinger(1734),Moët et Chandon(1743) andVeuve Clicquot(1772).[10]

The nineteenth century saw an explosive growth in Champagne production going from a regional production of 300,000 bottles a year in 1800 to 20 million bottles in 1850.[13]

Rivalry with Burgundy

[edit]A strong influence on Champagne wine production was the centuries-old rivalry between the region andBurgundy.From the key market of Paris to the palace ofLouis XIV of FranceatVersailles,proponents of Champagne and Burgundy would compete for dominance. For most of his life, Louis XIV would drink only Champagne wine with the support of his doctorAntoine d'Aquinwho advocated the King drink Champagne with every meal for the benefit of his health. As the King aged and his ailments increased, competing doctors would propose alternative treatments with alternative wines, to soothe the King's ills. One of these doctors,Guy-Crescent Fagonconspired with the King's mistress to oust d'Aquin and have himself appointed as Royal Doctor. Fagon quickly attributed the King's continuing ailments to Champagne and ordered that onlyBurgundy winemust be served at the royal table.[14]

This development had a ripple effect throughout both regions and in the Paris markets. Both Champagne and Burgundy were deeply concerned with the "healthiness" reputation of their wines, even to the extent of paying medical students to write theses touting thehealth benefit of their wines.These theses were then used as advertising pamphlets that were sent to merchants and customers. The Faculty of Medicine in Reims published several papers to refute Fagon's claim that Burgundy wine was healthier than Champagne. In response, Burgundian winemakers hired physicianJean-Baptiste de Salins,dean of the medical school inBeaune,to speak to a packed auditorium at the Paris Faculty of Medicine. Salins spoke favorably of Burgundy wine's deep color and robust nature and compared it to the pale red color of Champagne and the "instability"of the wine to travel long distances and the flaws of the bubbles from when secondary fermentation would take place. The text of his speech was published in newspapers and pamphlets throughout France and had a damaging effect on Champagne sales.[15]

The war of words would continue for another 130 years with endless commentary from doctors, poets, playwrights and authors all arguing for their favorite region and their polemics being reproduced in advertisements for Burgundy and Champagne. On a few occasions, the two regions were on the brink ofcivil war.[16]A turning point occurred when several Champagne wine makers abandoned efforts to produce red wine in favor of focusing on harnessing the effervescent nature of sparkling Champagne. As the bubbles became more popular, doctors throughout France andEuropecommented on the health benefits of the sparkling bubbles which were said to curemalaria.As more Champenois winemakers embarked on this new and completely different wine style, the rivalry with Burgundy mellowed and eventually waned.[16]

Classifications and vineyard regulations

[edit]

In 1927,viticulturalboundaries of Champagne were legally defined and split into five wine-producing districts: TheAube,Côte des Blancs,Côte de Sézanne,Montagne de Reims,andVallée de la Marne.This area covered in 2008 33,500hectares(76,000 acres) of vineyards around 319 villages that were home to 5,000 growers who made their own wine and 14,000 growers who only sold grapes.[4][17][18]

The different districts produce grapes of varying characteristics that are blended by the Champagne houses to create their distinct house styles. The Pinots of the Montagne de Reims that are planted on northern facing slopes are known for their high levels of acid and the delicacy they add to the blend. The grapes on the southern facing slope add more power and character. Grapes across the district contribute to thebouquetand headiness. The abundance of southern facing slopes in the Vallée de la Marne produces the ripest wines with full aroma. The Côte des Blancs grapes are known for their finesse and the freshness they add to blends with the extension of the nearby Côte de Sézanne offering similar though slightly less distinguished traits.[11]

In 1941, theComité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne(CIVC) was formed with the purpose of protecting Champagne's reputation and marketing forces as well as setting up and monitoring regulations for vineyard production and vinification methods. Champagne is the only region that is permitted to excludeAOCorAppellation d'Origine Contrôléefrom their labels.[4]

For each vintage, the CIVC rated the villages of the area based on the quality of their grapes and vineyards. The rating was then used to determine the price and the percentage of the price that growers get. TheGrand Crurated vineyards received 100 percent rating which entitled the grower to 100% of the price.Premier Cruswere vineyards with 90–99% ratings whileDeuxième Crusreceived 80–89% ratings.[2] Underappellationrules, around 4,000 kilograms (8,800 pounds) of grapes can bepressedto create up to 673gallons(either 2,550 L or 3,060 L) of juice. The first 541 gallons (either 2,050 L or 2,460 L) are thecuvéeand the next 132 gallons (either 500 L or 600 L) are thetaille.Prior to 1992, a secondtailleof 44 gallons (either 167 L or 200 L) was previously allowed. ForvintageChampagne, 100% of the grapes must come from that vintage year while non-vintage wine is a blend of vintages. Vintage champagne must spend a minimum of three years of aging. There are no regulations about how long it must spend on itslees,but some of the premier Champagne houses keep their wines onleesfor upwards of five to ten years. Non-vintage Champagne must spend a minimum of 15 months of aging but only a minimum of 12 months on the lees. Most of the Champagne houses keep their wines on the lees throughout the entire aging period because it is more expensive to bottle the wine before aging it, as opposed to bottling and shipping the product in a single step at the end of the fermentation-and-aging process.[2]

Revision of the Champagne region

[edit]

The worldwide demand for Champagne has been continuously increasing throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. A record in worldwide shipping of Champagne (including domestic French consumption) of 327 million bottles was set in 1999 in anticipation of end ofmillenniumcelebrations, and a new record was set in 2007 at 338.7 million bottles.[19]Since the entire vineyard area authorized by the 1927 AOC regulations is now under cultivation, various ways of expanding the production have been considered. The allowed yield was increased (to a maximum of 15,500 kg per hectare during an experimental period from 2007 to 2011[20]) and the possibility of revising the production region was examined.

After an extensive review of vineyard conditions in and around the existing Champagne region,INAOpresented a proposal to revise the region on March 14, 2008. The proposal was prepared by a group of five experts in the subjects ofhistory,geography,geology,phytosociologyandagronomy,working from 2005.[21]The proposal means expanding the region to cover vineyards in 357 rather than 319 villages.[17]This is to be achieved by adding vineyards in forty villages while simultaneously removing two villages in theMarnedepartment that were included in the 1927 regulations,GermaineandOrbais-l'Abbaye.[22]

The proposed 40 new Champagne villages are located in fourdépartements:[23][24]

- 22 in Marne:Baslieux-les-Fismes,Blacy,Boissy-le-Repos,Bouvancourt,Breuil-sur-Vesle,Bussy-le-Repos,Champfleury,Courlandon,Courcy,Courdemanges,Fismes,Huiron,La Ville-sous-Orbais,Le Thoult-Trosnay,Loivre,Montmirail,Mont-sur-Courville,Peas,Romain,Saint-Loup,Soulanges,andVentelay.

- 15 inAube:Arrelles,Balnot-la-Grange,Bossancourt,Bouilly,Étourvy,Fontvannes,Javernant,Laines-aux-Bois,Macey,Messon,Prugny,Saint-Germain-l'Épine,Souligny,TorvilliersandVillery.

- Two inHaute-Marne:Champcourtand Harricourt.

- One,Marchais-en-Brie,inAisne.

The INAO proposal was to be subject to review before being made into law and was immediately questioned in numerous public comments. The mayor of one of the villages to be delisted, Germaine, immediately appealed against INAO's proposal, with the possibility of additional appeals by vineyard owners.[17][25]The initial review process is expected to be finished by early 2009. This will be followed by another review of the specific parcels that will be added or deleted from the appellation. The earliest vineyard plantings are expected around 2015, with their product being marketed from around 2021. However, the price of land that are allowed to be used for Champagne production is expected to immediately rise from 5,000 to one millioneuroper hectare.

While some critics have feared the revision of the Champagne region is about expanding production irrespective of quality, British wine writer and Champagne expertTom Stevensonhas pointed out that the proposed additions constitute a consolidation rather than expansion. The villages under discussion are situated in gaps inside the perimeter of the existing Champagne regions rather than outside it.[21]

As of 2019, the expansion had not happened, with a final decision expected in 2023[26]or 2024.[27]

Production other than sparkling wine

[edit]While totally dominating the region's production, sparkling Champagne is not the only product that is made from the region's grapes. Non-sparkling still wines, like those made around the villageBouzy,are sold under the appellation labelCoteaux Champenois.[11]There is also a rosé appellation in the region,Rosé des Riceys.The regionalvin de liqueuris calledRatafiade Champagne.Since the profit of making sparkling Champagne from the region's grape is now much higher, production of these non-sparkling wines and fortified wines is very small.

Thepomacefrom the grape pressing is used to makeMarcde Champagne,and in this case the production does not compete with that of Champagne, since the pomace is a by-product of wine production.

Traditions

[edit]The end of harvest in Champagne is marked by a celebration known asla Fête du Cochelet.[28]At Reims, "St Jean is the patron of the cellar staff and those engaged in work connected with Champagne."[29]

See also

[edit]- Champagne Riots

- Oeil de Perdrix,wine style believed to have been invented by the Champenois

References

[edit]- ^"Champagne Paris wine tours".Paris Digest. 2019.Retrieved2019-03-08.

- ^abcK. Gargett, P. Forrestal, & C. Fallis (2004).The Encyclopedic Atlas of Wine.Global Book Publishing. p. 164.ISBN1-74048-050-3.

- ^"Champagne Hillsides, Houses and Cellars".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.Retrieved12 December2021.

- ^abcdK. Gargett, P. Forrestal, & C. FallisThe Encyclopedic Atlas of Winepg 163 Global Book Publishing 2004ISBN1-74048-050-3

- ^abH. Johnson & J. RobinsonThe World Atlas of Winepg 79 Octopus Publishing Group 2005ISBN1-84000-332-4

- ^R. PhillipsA Short History of Winepg 75 HarperCollins 2000ISBN0-06-621282-0

- ^H. JohnsonVintage: The Story of Winepg 96–97 Simon & Schuster 1989ISBN0-671-68702-6

- ^H. JohnsonVintage: The Story of Winepg 210–211 Simon & Schuster 1989ISBN0-671-68702-6

- ^H. JohnsonVintage: The Story of Winepg 211 Simon & Schuster 1989ISBN0-671-68702-6

- ^abK. Gargett, P. Forrestal, & C. FallisThe Encyclopedic Atlas of Winepg 162 Global Book Publishing 2004ISBN1-74048-050-3

- ^abcH. Johnson & J. RobinsonThe World Atlas of Winepg 80 Octopus Publishing Group 2005ISBN1-84000-332-4

- ^H. JohnsonVintage: The Story of Winepg 212 Simon & Schuster 1989ISBN0-671-68702-6

- ^R. PhillipsA Short History of Winepg 241 HarperCollins 2000ISBN0-06-621282-0

- ^D. & P. KladstrupChampagnepg 32 HarperCollins PublishersISBN0-06-073792-1

- ^D. & P. KladstrupChampagnepg 33–34 HarperCollins PublishersISBN0-06-073792-1

- ^abD. & P. KladstrupChampagnepg 36 HarperCollins PublishersISBN0-06-073792-1

- ^abcKevany, Sophie (March 14, 2008)."New Champagne areas defined".Decanter.Retrieved2008-03-15.

- ^Bremner, Charles (2008-03-14)."Champagne region expanded to meet world demand".The Times.London.Retrieved2008-03-15.

- ^Fallowfield, Giles (March 4, 2008)."Champagne shipments and exports hit new high".Decanter.Retrieved2008-03-15.

- ^Fallowfield, Giles (October 22, 2007)."Record harvest in Champagne".Decanter. Archived fromthe originalon October 23, 2007.Retrieved2008-03-15.

- ^abWine-pages: Champagne's €6 billion expansionArchived2008-04-27 at theWayback Machine,by Tom Stevenson; written November 2007 and accessed on March 17, 2008

- ^Kevany, Sophie (March 14, 2008)."Winners and losers revealed in Champagne shake-up".Decanter. Archived fromthe originalon March 18, 2008.Retrieved2008-03-15.

- ^Fallowfield, Giles (November 10, 2007)."France aims to extend Champagne region".Decanter. Archived fromthe originalon December 16, 2007.Retrieved2008-03-15.

- ^Kevany, Sophie (March 17, 2008)."Champagne: the 40 new communes".Decanter. Archived fromthe originalon April 12, 2008.Retrieved2008-03-17.

- ^Kevany, Sophie (March 17, 2008)."Champagne: Germaine appeals, Orbay accepts".Decanter. Archived fromthe originalon April 15, 2008.Retrieved2008-03-17.

- ^"Pourquoi la Champagne va subir son plus grand bouleversement depuis 1927".France 3 Grand Est(in French).Retrieved16 June2022.

- ^Sage, Adam."Champagne region expansion uncorks grapes of wrath".Retrieved16 June2022.

- ^Ross, Harold Wallace; Shawn, William; Brown, Tina; Remnick, David; White, Katharine Sergeant Angell; Irvin, Rea; Angell, Roger (1963).The New Yorker.

- ^Price, Pamela Vandyke (1974).Eating and drinking in France today.Scribner. p. 219.ISBN9780684137568.