Chaos (cosmogony)

| Part ofa Mythology serieson |

| Chaoskampf orDrachenkampf |

|---|

|

| Comparative mythologyofsea serpents,dragonsanddragonslayers. |

Chaos(Ancient Greek:χάος,romanized:Kháos) is the mythological void state preceding thecreation of the universe(the cosmos) inancient near eastern cosmologyandearly Greek cosmology.It can also refer to an early state of the cosmos constituted of nothing but undifferentiated and indistinguishable matter.[1]

Etymology[edit]

Greekkháos(χάος) means 'emptiness,vast void,chasm,abyss',[2]related to the verbskháskō(χάσκω) andkhaínō(χαίνω) 'gape, be wide open', fromProto-Indo-European*ǵʰeh₂n-,[3]cognate toOld Englishgeanian,'to gape', whence Englishyawn.[4]

It may also mean space, the expanse of air, the nether abyss or infinitedarkness.[5]Pherecydes of Syros(fl. 6th century BC) interpretschaosas water, like something formless that can be differentiated.[6]

Chaoskampf[edit]

Chaoskampf(German:[ˈkaːɔsˌkampf];lit. 'the battle against chaos'),[7]also described as a "combat myth", is generally used to refer to a widespread mythological motif involving battle between aculture herodeity with a chaos monster, often in the form of asea serpentordragon.The term was first used with respect to the destruction of the chaos dragonTiamatin theEnūma Eliš,although it has been observed that the primeval state is one of a peaceful existence betweenAbzuandTiamatand chaos only ensues when Tiamat enters combat withMarduk.[7]

Today, theChaoskampfconcept is plagued by a lack of consistent definition and use of the term across many studies.[1]Nicolas Wyatt defines theChaoskampfcategory as follows:[8]

TheChaoskampfmyth is a category of divine combat narratives with cosmogonic overtones, though at times turned secondarily to other purposes, in which the hero god vanquishes a power or powers opposed to him, which generally dwell in, or are identified with, the sea, and are presented as chaotic, dissolutory forces.

It may also be used to refer to a dualistic battle between two gods, although in that context, an alternative term that has been proposed is "theomachy" whereas "Chaoskampf"may be restrained to refer to cosmic battles in the context of creation. For example, aChaoskampfmay be found in the Enuma Elish (the only ancient near eastern text to place a cosmic battle in the context of a creation narrative), but not in theBaal CycleorPsalm 74where a theomachy ensues betweenBaal/Yahwehand the sea serpentYam/Leviathanwithout being followed by creation.[9]The notion ofChaoskampfmay be further distinguished from a divine battle between a god and the enemy of his people.[10]

Parallel concepts appear in the Middle East and North Africa, such as the abstract conflict of ideas in the Egyptian duality ofMaatandIsfetor the battle ofHorusandSet,[11]or the more concrete parallel of the battle of [Torah] sense ( Rah)Rawith the chaos serpentApophis.

Greco-Roman tradition[edit]

| Greek deities series |

|---|

| Primordial deities |

Hesiodand thePre-Socraticsuse the Greek term in the context ofcosmogony.Hesiod's Chaos has been interpreted as either "the gaping void above the Earth created when Earth and Sky are separated from their primordial unity" or "the gaping space below the Earth on which Earth rests."[12]Passages in Hesiod'sTheogonysuggest that Chaos was located below Earth but aboveTartarus.[13][14]Primal Chaos was sometimes said to be the true foundation of reality, particularly by philosophers such asHeraclitus.

Cosmology in early Greece[edit]

InHesiod'sTheogony,Chaos was the first thing to exist: "at first Chaos came to be" (or was),[15]but next (possibly out of Chaos) cameGaia,Tartarus,andEros(elsewhere the nameErosis used for a son ofAphrodite).[a]Unambiguously "born" from Chaos wereErebusandNyx.[16][17]For Hesiod, Chaos, like Tartarus, though personified enough to have borne children, was also a place, far away, underground and "gloomy," beyond which lived theTitans.[18]And, like the earth, the ocean, and the upper air, it was also capable of being affected by Zeus's thunderbolts.[19]

The notion of the temporal infinity was familiar to the Greek mind from remote antiquity in the religious conception ofimmortality.[20]The main object of the first efforts to explain the world remained the description of its growth, from a beginning. They believed that the world arose out from a primal unity, and that this substance was the permanent base of all its being.Anaximanderclaims that the origin isapeiron(the unlimited), a divine and perpetual substance less definite than the common elements (water,air,fire,andearth) as they were understood to the early Greek philosophers. Everything is generated fromapeiron,and must return there according to necessity.[21]A conception of the nature of the world was that the earth below its surface stretches down indefinitely and has its roots on or aboveTartarus,the lower part of the underworld.[22]In a phrase ofXenophanes,"The upper limit of the earth borders on air, near our feet. The lower limit reaches down to the" apeiron "(i.e. the unlimited)."[22]The sources and limits of the earth, the sea, the sky,Tartarus,and all things are located in a great windy-gap, which seems to be infinite, and is a later specification of "chaos".[22][23]

Classical Greece[edit]

InAristophanes's comedyBirds,first there was Chaos, Night, Erebus, and Tartarus, from Night came Eros, and from Eros and Chaos came the race of birds.[24]

At the beginning there was only Chaos, Night, dark Erebus, and deep Tartarus. Earth, the air and heaven had no existence. Firstly, blackwinged Night laid a germless egg in the bosom of the infinite deeps of Erebus, and from this, after the revolution of long ages, sprang the graceful Eros with his glittering golden wings, swift as the whirlwinds of the tempest. He mated in deep Tartarus with dark Chaos, winged like himself, and thus hatched forth our race, which was the first to see the light. That of the Immortals did not exist until Eros had brought together all the ingredients of the world, and from their marriage Heaven, Ocean, Earth, and the imperishable race of blessed gods sprang into being. Thus our origin is very much older than that of the dwellers in Olympus. We [birds] are the offspring of Eros; there are a thousand proofs to show it. We have wings and we lend assistance to lovers. How many handsome youths, who had sworn to remain insensible, have opened their thighs because of our power and have yielded themselves to their lovers when almost at the end of their youth, being led away by the gift of a quail, a waterfowl, a goose, or a cock.

InPlato's Timaeus, the main work of Platonic cosmology, the concept of chaos finds its equivalent in the Greek expressionchôra,which is interpreted, for instance, as shapeless space (chôra) in which material traces (ichnê) of the elements are in disordered motion (Timaeus 53a–b). However, the Platonicchôrais not a variation of theatomisticinterpretation of the origin of the world, as is made clear by Plato's statement that the most appropriate definition of the chôra is "a receptacle of all becoming – its wetnurse, as it were" (Timaeus 49a), notabene a receptacle for the creative act of the demiurge, the world-maker.[25]

Aristotle,in the context of his investigation of the concept of space in physics, "problematizes the interpretation of Hesiod's chaos as 'void' or 'place without anything in it'.[26]Aristotle understands chaos as something that exists independently of bodies and without which no perceptible bodies can exist. 'Chaos' is thus brought within the framework of an explicitly physical investigation. It has now outgrown the mythological understanding to a great extent and, in Aristotle's work, serves above all to challenge the atomists who assert the existence of empty space. "[25]

Roman tradition[edit]

ForOvid,(43 BC – 17/18 AD), in hisMetamorphoses,Chaos was an unformed mass, where all the elements were jumbled up together in a "shapeless heap".[27]

- Before the ocean and the earth appeared— before the skies had overspread them all—

- the face of Nature in a vast expanse was naught but Chaos uniformly waste.

- It was a rude and undeveloped mass, that nothing made except a ponderous weight;

- and all discordant elements confused, were there congested in a shapeless heap.[28]

According toHyginus:"From Mist (Caligo) came Chaos. From Chaos and Mist, came Night (Nox), Day (Dies), Darkness (Erebus), and Ether (Aether). "[29][b]AnOrphic traditionapparently had Chaos as the son ofChronusandAnanke.[31]

Biblical tradition[edit]

Since the classic 1895 German workSchöpfung und Chaos in Urzeit und EndzeitbyHermann Gunkel,various historians in the field of modernbiblical studieshave associated the theme of chaos in the earlier Babylonian cosmology (and now other cognate narratives fromancient near eastern cosmologies) with theGenesis creation narrative.[32][33]Besides Genesis, other books of the Old Testament, especially a number ofPsalms,some passages inIsaiahandJeremiahand theBook of Jobare relevant.[34][35][36]

One locus of focus has been with respect to the termabyss/tohu wa-bohuinGenesis 1:2.The term may refer to a state of non-being prior to creation[37][38]or to a formless state. In theBook of Genesis,the spirit of God is moving upon the face of the waters, displacing the earlier state of the universe that is likened to a "watery chaos" upon which there ischoshek(which translated from the Hebrew is darkness/confusion).[20][39]Some scholars, however, reject the association between biblical creation and notions of chaos from Babylonian and other (such as Chinese) myths. The basis is that the terms themselves in Genesis 1:2 are not semantically related to chaos, and that the entire cosmos exists in a state of chaos in Babylonian, Chinese, and other myths, whereas at most this can be said of the earth in Genesis.[40]The presence ofChaoskampfin the biblical tradition is now contentious.[41][42][43]

TheSeptuagintmakes no use ofχάοςin the context of creation, instead using the term forגיא,"cleft, gorge, chasm", inMicah1:6 andZachariah14:4.[44]TheVulgate,however, renders the χάσμα μέγα or "great gulf" betweenheavenandhellinLuke16:26 aschaos magnum.

This model of a primordialstate of matterhas been opposed by theChurch Fathersfrom the 2nd century, who posited acreationex nihiloby an omnipotentGod.[45]

Hawaiian tradition[edit]

InHawaiian folklore,a triad of deities known as the "Ku-Kaua-Kahi" (a.k.a. "Fundamental Supreme Unity" ) were said to have existed prior to and during Chaos ever since eternity, or put in Hawaiian terms, "mai ka po mai," meaning "from the time of night, darkness, Chaos." They eventually broke the surroundingPo( "night" ), and light entered the universe. Next the group created three heavens for dwelling areas together with the Earth, Sun, Moon, stars, and assistant spirits.[46]

Gnosticism[edit]

According to theGnosticOn the Origin of the World,Chaos was not the first thing to exist. When the nature of the immortalaeonswas completed,Sophiadesired something like thelight which first existedto come into being. Her desire appears as a likeness with incomprehensible greatness that covers the heavenly universe, diminishing its inner darkness while a shadow appears on the outside which causes Chaos to be formed. From Chaos every deity including theDemiurgeis born.[47]

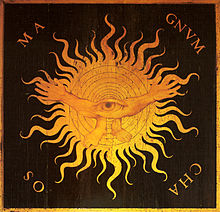

Alchemy and Hermeticism[edit]

The Greco-Roman tradition ofprima materia,notably including the 5th- and 6th-centuryOrphiccosmogony, was merged with biblical notions (Tehom) inChristianityand inherited byalchemyandRenaissance magic.[citation needed]

The cosmic egg of Orphism was taken as the raw material for the alchemicalmagnum opusin early Greek alchemy. The first stage of the process of producing thephilosopher's stone,i.e.,nigredo,was identified with chaos. Because of association with theGenesis creation narrative,where "the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters" (Gen. 1:2), Chaos was further identified with theclassical elementofWater.

Ramon Llull(1232–1315) wrote aLiber Chaos,in which he identifies Chaos as the primal form or matter created by God. Swiss alchemistParacelsus(1493–1541) useschaossynonymously with "classical element" (because the primeval chaos is imagined as a formless congestion of all elements). Paracelsus thus identifiesEarthas "the chaos of thegnomi",i.e., the element of thegnomes,through which these spirits move unobstructed as fish do through water, or birds through air.[48]An alchemical treatise byHeinrich Khunrath,printed in Frankfurt in 1708, was entitledChaos.[49]The 1708 introduction states that the treatise was written in 1597 in Magdeburg, in the author's 23rd year of practicing alchemy.[50]The treatise purports to quote Paracelsus on the point that "The light of the soul, by the will of the Triune God, made all earthly things appear from the primal Chaos."[51]Martin Ruland the Younger,in his 1612Lexicon Alchemiae,states, "A crude mixture of matter or another name forMateria PrimaisChaos,as it is in the Beginning. "

The termgasinchemistrywas coined by Dutch chemistJan Baptist van Helmontin the 17th century directly based on theParacelsiannotion of chaos. Thegingasis due to the Dutch pronunciation of this letter as aspirant,also employed to pronounce Greekχ.[52]

Modern usage[edit]

The termchaoshas been adopted in moderncomparative mythologyandreligious studiesas referring to the primordial state before creation, strictly combining two separate notions of primordial waters or a primordial darkness from which a new order emerges and a primordial state as a merging of opposites, such as heaven and earth, which must be separated by a creator deity in an act ofcosmogony.[53]In both cases, chaos referring to a notion of a primordial state contains the cosmosin potentiabut needs to be formed by ademiurgebefore the world can begin its existence.

Use ofchaosin the derived sense of "complete disorder or confusion" first appears in ElizabethanEarly Modern English,originally implying satirical exaggeration.[54]"Chaos"in the well-defined sense ofchaotic complex systemis in turn derived from this usage.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^According to Gantz (1996)[16]pp. 4–5: "With regard to all three of these figures – Gaia, Tartaros, and Eros – we should note that Hesiod does not say they arosefrom(as opposed toafter) Chaos, although this is often assumed. "For example, Morford, p. 57, makes these three descendants of Chaos saying they came" presumably out of Chaos, just as Hesiod actually states that 'from Chaos' came Erebus and dark Night ". Tripp, p. 159, says simply that Gaia, Tartarus and Eros, came"out of Chaos, or together with it".Caldwell (p. 33 n. 116–122) however, interprets Hesiod as saying that Chaos, Gaia, Tartarus, and Eros, all"are spontaneously generated without source or cause".Later writers commonly make Eros the son ofAphroditeandAres,though several other parentages are also given.[16]

- ^Bremmer (2008)[30]translatesCaligoas 'Darkness'; according to him:

"Hyginus... started hisFabulaewith a strange hodgepodge of Greek and Roman cosmogonies and early genealogies. It begins as follows:- Ex Caligine Chaos. Ex Chao et Caligine Nox Dies ErebusAether.— (Praefatio 1)

- Ex Caligine Chaos. Ex Chao et Caligine Nox Dies ErebusAether.— (Praefatio 1)

References[edit]

- ^abTsumura 2022,p. 253.

- ^West, p. 192 line 116Χάος,"best translated Chasm"; Englishchasmis a loan from Greekχάσμα,which is root-cognate with χάος. Most, p. 13, translatesΧάοςas "Chasm", and notes: (n. 7): "Usually translated as 'Chaos'; but that suggests to us, misleadingly, a jumble of disordered matter, whereas Hesiod's term indicates instead a gap or opening".

- ^R. S. P. Beekes,Etymological Dictionary of Greek,Brill, 2009, pp. 1614 and 1616–7.

- ^"chaos".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^Lidell-Scott,A Greek–English Lexiconchaos

- ^Kirk, Raven & Schofield 2003,p. 57

- ^abTsumura 2022,p. 255.

- ^Wyatt 2022,p. 244.

- ^Tsumura 2022,p. 256, 269–270.

- ^Tsumura 2022,p. 256–257.

- ^Wyatt, Nicolas (2001-12-01).Space and Time in the Religious Life of the Near East.A&C Black. pp. 210–211.ISBN978-0-567-04942-1.

- ^ Moorton, Richard F. Jr. (2001)."Hesiod as Precursor to the Presocratic Philosophers: A Voeglinian View".Louisiana State University. Archived fromthe originalon 2008-12-11.Retrieved2008-12-04.

- ^Gantz (1996,p. 3)

- ^ Hesiod.Theogony.813–814,700,740– via Perseus,Tufts University.

- ^Gantz (1996,p. 3) says "the Greek will allow both".

- ^abcGantz (1996,pp. 4–5)

- ^Hesiod.Theogony.123– via Persius,Tufts University.

- ^Hesiod.Theogony.814– via Persius,Tufts University.

And beyond, away from all the gods, live the Titans, beyond gloomy Chaos

- ^Hesiod.Theogony.740– via Perseus,Tufts University.

- ^abGuthrie, W.K.C. (2000).A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans.Cambridge University Press. pp. 59, 60, 83.ISBN978-0-521-29420-1.Archived fromthe originalon 2014-01-03.

- ^Nilsson, Vol.I, p.743[full citation needed];Guthrie (1952,p. 87)

- ^abcKirk, Raven & Schofield 2003,pp. 9, 10, 20

- ^Hesiod.Theogony.740–765– via Perseus,Tufts University.

- ^Aristophanes 1938,693–699;Morford, pp 57–58. Caldwell, p. 2, describes this avian-declared theogony as "comedic parody".

- ^abLobenhofer, Stefan (2020)."Chaos".In Kirchhoff, Thomas (ed.).Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie[Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature].University of Heidelberg.doi:10.11588/oepn.2019.0.68092.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^Aristotle.Physics.IV 1 208b27–209a2 [...]

- ^Ovid.Metamorphoses.1.5 ff.– via Perseus,Tufts University.

- ^Ovid & More 1922,1.5ff.

- ^Gaius Julius Hyginus.Fabulae.Translated by Smith; Trzaskoma.Preface.

- ^abBremmer (2008,p. 5)

- ^Ogden 2013,pp. 36–37.

- ^Tsumura 2022,p. 254.

- ^H. Gunkel,Genesis,HKAT I.1, Göttingen, 1910.

- ^Michaela Bauks,Chaos / Chaoskampf,WiBiLex – Das Bibellexikon (2006).

- ^Michaela Bauks,Die Welt am Anfang. Zum Verhältnis von Vorwelt und Weltentstehung in Gen. 1 und in der altorientalischen Literatur(WMANT 74), Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1997.

- ^Michaela Bauks, ''Chaos' als Metapher für die Gefährdung der Weltordnung', in: B. Janowski / B. Ego,Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte(FAT 32), Tübingen, 2001, 431–464.

- ^Tsumura, D.,Creation and Destruction. A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament,Winona Lake/IN, 1989, 2nd ed. 2005,ISBN978-1-57506-106-1.

- ^C. Westermann,Genesis, Kapitel 1–11,(BKAT I/1), Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1974, 3rd ed. 1983.

- ^Genesis 1:2, English translation (New International Version)(2011):BibleGatewayBiblica incorporation

- ^Tsumura 2022,p. 255, 281.

- ^Watson 2005.

- ^Tsumura 2020.

- ^Tsumura 2022.

- ^"Lexicon:: Strong's H1516 – gay'".blueletterbible.org.

- ^Gerhard May,Schöpfung aus dem Nichts. Die Entstehung der Lehre von der creatio ex nihilo,AKG 48, Berlin / New York, 1978, 151f.

- ^Thrum, Thomas (1907).Hawaiian Folk Tales.A. C. McClurg.p. 15.

- ^Marvin Meyer;Willis Barnstone(2009). "On the Origin of the World".The Gnostic Bible.Shambhala.Retrieved2021-10-14.

- ^De Nymphis etc. Wks. 1658 II. 391[full citation needed]

- ^Khunrath, Heinrich(1708).Vom Hylealischen, das ist Pri-materialischen Catholischen oder Allgemeinen Natürlichen Chaos der naturgemässen Alchymiae und Alchymisten: Confessio.

- ^Szulakowska 2000,p. 79.

- ^Szulakowska (2000,p. 91), quotingKhunrath (1708,p. 68)

- ^"halitum illum Gas vocavi, non longe a Chao veterum secretum." Ortus Medicinæ, ed. 1652, p. 59a, cited after theOxford English Dictionary.

- ^Mircea Eliade,article "Chaos" inReligion in Geschichte und Gegenwart,3rd ed. vol. 1, Tübingen, 1957, 1640f.

- ^Stephen Gosson,The schoole of abuse, containing a plesaunt inuectiue against poets, pipers, plaiers, iesters and such like caterpillers of a commonwelth(1579), p. 53 (cited afterOED): "They make their volumes no better than [...] a huge Chaos of foule disorder."

Sources[edit]

- Aristophanes(1938)."Birds".In O'Neill, Jr, Eugene (ed.).The Complete Greek Drama.Vol. 2. New York: Random House – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Aristophanes(1907). Hall, F.W.; Geldart, W.M. (eds.).Aristophanes Comoediae(in Greek). Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Bremmer, Jan N. (2008).Greek Religion and Culture, the Bible and the Ancient Near East.Jerusalem Studies in Religion and Culture. Brill.ISBN978-90-04-16473-4.LCCN2008005742.

- Caldwell, Richard (1987).Hesiod's Theogony.Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company.ISBN978-0-941051-00-2.

- Clifford, Richard J (April 2007). "Book Review: Creation and Destruction: A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament".Catholic Biblical Quarterly.69(2).JSTOR43725990.

- Day, John (1985).God's conflict with the dragon and the sea: echoes of a Canaanite myth in the Old Testament.Cambridge Oriental Publications.ISBN978-0-521-25600-1.

- Gantz, Timothy (1996).Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources.Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN978-0-8018-5360-9.

- Guthrie, W. K. (April 1952). "The Presocratic World-picture".The Harvard Theological Review.45(2): 87–104.doi:10.1017/S0017816000020745.S2CID162375625.

- Hesiod(1914). "Theogony".The Homeric Hymns and Homerica(in English and Greek). Translated by Evelyn-White, Hugh G. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press – via Perseus Digital Library.Greek text available from the same website.

- Hyginus.Grant, Mary (ed.).Fabulae from The Myths of Hyginus.Translated by Grant, Mary. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies – via Topos Text Project.

- Jaeger, Werner (1952).The theology of the early Greek philosophers: the Gifford lectures 1936.Oxford: Clarendon Press.OCLC891905501.

- Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J. E.; Schofield, M. (2003).The Presocratic philosophers.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-27455-9.

- Lobenhofer, Stefan (2020):Chaos.In: Kirchhoff, Thomas (ed.):Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature / Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie,doi: 10.11588/oepn.2019.0.68092;https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/oepn/article/view/69709.

- Morford, Mark P. O., Robert J. Lenardon,Classical Mythology,Eighth Edition, Oxford University Press, 2007.ISBN978-0-19-530805-1.

- Most, G. W.,Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia,Loeb Classical Library,No. 57, Cambridge, MA, 2006ISBN978-0-674-99622-9.Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Ogden, Daniel (2013).Dragons, Serpents, and Slayers in the Classical and early Christian Worlds: A sourcebook.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-992509-4.

- Publius Ovidius Naso(1892). Magnus, Hugo (ed.).Metamorphoses(in Latin). Gotha, Germany: Friedr. Andr. Perthes – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Publius Ovidius Naso(1922).Metamorphoses.Translated by More, Brookes. Boston: Cornhill Publishing Co – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Smith, William(1873)."Chaos".Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.London – via Perseus Digital Library.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Szulakowska, Urszula (2000).The alchemy of light: geometry and optics in late Renaissance alchemical illustration.Symbola et Emblemata – Studies in Renaissance and Baroque Symbolism. Vol. 10. BRILL.ISBN978-90-04-11690-0.

- Tripp, Edward,Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology,Thomas Y. Crowell Co; First edition (June 1970).ISBN0-690-22608-X.*West, M. L.(1966),Hesiod: Theogony,Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-814169-6.

- Tsumura, David Toshio (2020)."The Chaoskampf Myth in the Biblical Tradition".Journal of the American Oriental Society.140(4): 963–970.doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.4.0963.JSTOR10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.4.0963.

- Tsumura, David Toshio (2022)."Chaos andChaoskampfin the Bible: Is "Chaos" a Suitable Term to Describe Creation or Conflict in the Bible? ".In Watson, Rebecca S.; Curtis, Adrian H.W. (eds.).Conversations on Canaanite and Biblical Themes Creation, Chaos and Monotheism.De Gruyter. pp. 253–281.

- Watson, Rebecca S. (2005).Chaos Uncreated: A Reassessment of the Theme of "Chaos" in the Hebrew Bible.De Gruyter.doi:10.1515/9783110900866.ISBN978-3-11-017993-4.

- Wyatt, Nick (2005) [1998]. "Arms and the King: The Earliest Allusions to theChaoskampfMotif and their Implications for the Interpretation of the Ugaritic and Biblical Traditions ".There's such divinity doth hedge a king: selected essays of Nicolas Wyatt on royal ideology in Ugaritic and Old Testament literature.Society for Old Testament Study monographs, Ashgate Publishing. pp. 151–190.ISBN978-0-7546-5330-1.

- Wyatt, Nicolas (2022)."Distinguishing Wood and Trees in the Waters: Creation in Biblical Thought".In Watson, Rebecca S.; Curtis, Adrian H.W. (eds.).Conversations on Canaanite and Biblical Themes Creation, Chaos and Monotheism.De Gruyter. pp. 203–252.

Further reading[edit]

- Miller, Robert D. (2014). "Tracking the Dragon across the Ancient Near East".Archiv Orientální.82:225–45.