Cherub

Acherub(/ˈtʃɛrəb/;[1]pl.:cherubim;Hebrew:כְּרוּבkərūḇ,pl.כְּרוּבִיםkərūḇīm) are one of the unearthly beings inAbrahamic religions.The numerous depictions of cherubim assign to them many different roles, such as protecting the entrance of theGarden of Eden.[2]

Abrahamic religious traditions

[edit]InJewish angelic hierarchy,cherubim have the ninth (second-lowest) rank inMaimonides'Mishneh Torah(12th century), and the third rank in Kabbalistic works such asBerit Menuchah(14th century). The Christian workDe Coelesti Hierarchiaplaces them in the highest rank alongsideSeraphimandThrones.[3]

InIslam,al-karubiyyin"cherubim" oral-muqarrabin"the Close" refers to the highest angels nearGod,[4]in contrast to the messenger angels. They include theBearers of the Throne,the angels around the throne, and thearchangels.[5]The angels of mercy subordinative to Michael are also identified as cherubim. InIsma'ilism,there areSeven Archangelsreferred to as cherubim.[6]

As described inEzekiel 1,"[E]ach had four faces, and each of them had four wings; the legs of each were [fused into] a single rigid leg, and the feet of each were like a single calf’s hoof; and their sparkle was like the luster of burnished bronze."[7]In Ezekiel and some Christian icons, the cherub is depicted as having two pairs of wings and four faces, thehayyoth:that of alion(representative of allwild animals), anox(domestic animals), ahuman(humanity), and aneagle(birds).[8](pp 2–4)[9]

Later tradition ascribes to them a variety of physical appearances.[8](pp 2–4)Some earlymidrashliterature conceives of them as non-corporeal. In Western Christian tradition, cherubim have become associated with theputtoderived fromCupidinclassical antiquity,resulting in depictions of cherubim as small, plump, winged boys.[8](p 1)

Cherubim are also mentioned in theSecond Treatise of the Great Seth,a 3rd-centuryGnosticwriting.[10]

Etymology

[edit]Delitzch'sAssyrisches Handwörterbuch(1896) connected the namekeruvwith Assyriankirubu(a name of thesheduorlamassu) andkarabu( "great, mighty" ).

Karppe(1897) glossed Babyloniankarâbuas "propitious" rather than "mighty".[2][11]

Dhorme(1926) connected the Hebrew name toAssyriankāribu(diminutivekurību), a term used to refer to intercessory beings (and statues of such beings) that plead with the gods on behalf of humanity.[8](pp 3–4)

Thefolk etymologyconnectingcherubto a Hebrew word for "youthful" is due toAbbahu(3rd century).[8](p 1)

Functions

[edit]

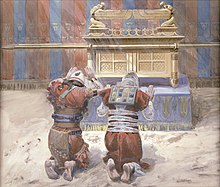

The Israelite cherubim are described as fulfilling a variety of functions – most often, they are described as bolstering the throne ofYahweh.Ezekiel's vision of the cherubim also emulate this, as the conjoined wingspan of the four cherubim is described as forming the boundary of the divine chariot. Likewise, on the "mercy seat"of theArk of the Covenant,two cherubim are described as bounding the ark and forming a space through which Yahweh would appear – however, aside from the instruction that they be beaten out of the sides of the ark, there are no details about these cherubim specified in the text. The status of thecherubimas constituting a sort-of vehicle for Yahweh is present in Ezekiel's visions, theBooks of Samuel,[12]the parallel passages in the laterBooks of Chronicles,[13]and passages in the early[2]Psalms:for example, "and he rode upon a cherub and did fly: and he was seen upon the wings of the wind."[14][15]

The traditional Hebrew conception of cherubim as guardians of theGarden of Edenis backed by the belief of beings of superhuman power and devoid of human feelings, whose duty it was to represent the gods, and as guardians of their sanctuaries to repel intruders; these conceptions in turn are similar to an account found on Tablet 9 of the inscriptions found atNimrud.[2]

Appearance

[edit]

Aside from Ezekiel's vision, no detailed attestations ofcherubimsurvive, and Ezekiel's description of thetetramorphbeing may not be the same as thecherubimof the historic Israelites.[16]All that can be gleaned about thecherubimof the Israelites come from potential equivalences in the cultures which surrounded them.

The appearance of thecherubimcontinue to be a subject of debate.Mythological hybridsare common in the art of theAncient Near East.One example is the Babylonianlamassuorshedu,a protective spirit with asphinx-like form, possessing the wings of an eagle, the body of a lion or bull, and the head of a king. This was adopted largely inPhoenicia.The wings, because of their artistic beauty and symbolic use as a mark of creatures of theheavens,soon became the most prominent part, and animals of various kinds were adorned with wings; consequently, wings were bestowed also upon human forms,[2]thus leading to the stereotypical image of anangel.[17]

William F. Albright(1938) argued that "the winged lion with human head" found in Phoenicia andCanaanfrom theLate Bronze Ageis "much more common than any other winged creature, so much so that its identification with the cherub is certain".[8](pp 2–4)A possibly related source is the human-bodiedHittitegriffin,which, unlike other griffins, appear almost always not as a fierce bird of prey, but seated in calm dignity, like an irresistible guardian of holy things;[2][17]some have proposed that the wordgriffin(γρύψ) may be cognate withcherubim(kruv>grups).[18][19]While Ezekiel initially describes the tetramorphcherubimas having

the face of a man... the face of a lion... the face of an ox... and... the face of an eagle

in thetenth chapterthis formula is repeated as

the face of the cherub... the face of a man... the face of a lion... the face of an eagle

which (given that "ox" has apparently been substituted with "the cherub" ) some have taken to imply thatcherubimwere envisioned to have the head of abovine.

In particular resonance with the idea of cherubim embodying the throne of God, numerous pieces of art from Phoenicia,Ancient Egypt,and evenTel Megiddoin northern Israel depict kings or deities being carried on their thrones by hybrid winged creatures.[17]

If this animalistic form is how the ancientIsraelitesenvisioned cherubim, it raises more questions than it answers. For one, it is difficult to visualize the cherubim of theArk of the Covenantas quadrupedal creatures with backward-facing wings, as these cherubim were meant to face each other and have their wings meet, while still remaining on the edges of the cover from which they were beaten. At the same time, these creatures have little to no resemblance to thecherubimin Ezekiel's vision.

On the other hand, even ifcherubimhad a morehumanoidform, this still would not entirely match Ezekiel's vision and likewise seemingly clashes with the apparently equivalentarchetypesof the cultures surrounding the Israelites, which almost uniformly depicted beings which served analogous purposes to Israel'scherubimas largely animalistic in shape. All of this may indicate that the Israelite conception of thecherub's appearance may not have been wholly consistent.[16]

Hebrew Bible

[edit]The cherubim are the most frequently occurring heavenly creature in theHebrew Bible,as the Hebrew word appears 91 times.[8](pp 2–4)The first occurrence is in theBook of Genesis3:24. Despite these many references, the role of the cherubim is never explicitly elucidated.[8](p 1)While Israelite tradition must have conceived of the cherubim as guardians of theGarden of Eden[2]in which they guard the way to theTree of life,[20]they are often depicted as performing other roles; for example in theBook of Ezekiel,they transport Yahweh's throne. The cherub who appears in the "Song of David", a poem which occurs twice in the Hebrew Bible, in2 Samuel22 andPsalm 18,participates in Yahweh'stheophanyand is imagined as a vehicle upon which the deity descends to earth from heaven to rescue the speaker (see 2 Samuel 22:11, Psalm 18:10).[8](pp 84–85)

In Exodus 25:18–22, God tellsMosesto make multiple images of cherubim at specific points around theArk of the Covenant.[8](pp 2–4)Many appearances of the wordscherubandcherubimin the Bible refer to the gold cherubim images on themercy seatof the Ark, as well as images on the curtains of theTabernacleand inSolomon's Temple,including two measuring tencubitshigh.[21]

InIsaiah 37:16,Hezekiahprays, addressing God asHebrew:יֹשֵׁ֥ב כְּ֝רוּבִ֗ים,lit. 'enthroned above the cherubim', referring to themercy seat.In regards to this same phrase, which appears also in2 Kings 19,Eichler renders it "who dwells among the cherubim". Eichler's interpretation is in contrast to common translations for many years that rendered it as “who sits upon the cherubim”. This has implications for the understanding of whether the ark of the covenant inSolomon's Templewas Yahweh's throne or simply an indicator of Yahweh's immanence.[22]

Cherubim feature at some length in Ezekiel. While they first appear inEzekiel 1,in which they are transporting the throne of God by the Kebar (or Chebar, which was nearTel AbibinNippur), they are not called "cherubim" untilEzekiel 10.[23]In Ezekiel 1:5–11 they are described as having the likeness of a man and having four faces: that of a man, a lion (on the right side), and ox (on the left side), and an eagle. The four faces represent the four domains of God's rule: the man represents humanity; the lion, wild animals; the ox, domestic animals; and the eagle, birds.[24]These faces peer out from the center of an array of four wings; these wings are joined to each other, two of these are stretched upward, and the other two cover their bodies. Under their wings are human hands; their legs are described as straight, and their feet like those of a calf, shining like polished brass. Between the creatures glowing coals that moved between them could be seen, their fire "went up and down", and lightning burst forth from it. The cherubs also moved like flashes of lightning.

In Ezekiel 10, another full description of the cherubim appears with slight differences in details. Three of the four faces are the same – man, lion and eagle – but where chapter one has the face of an ox, Ezekiel 10:14 says "face of a cherub". Ezekiel equates the cherubim of chapter ten with the living creatures of chapter one in Ezekiel 10:15 "The cherubs ascended; those were the creatures (Hebrew:הַחַיָּ֔ה,romanized:ḥayā) that I had seen by the Chebar Canal "and in 20:10," They were the same creatures that I had seen below theGod of Israelat the Chebar Canal; so now I knew that they were cherubs. "In Ezekiel 41:18–20, they are portrayed as having two faces, although this is probably because they are depicted in profile.[8](pp 2–4)

In Judaism

[edit]

In rabbinic literature, the twocherubimare described as being human-like figures with wings, one a boy and the other a girl, placed on the opposite ends of theMercy seatin the inner-sanctum of God's house.[25]Solomon's Templewas decorated with Cherubs according to1 Kings 6,andAḥa bar Ya’akovclaimed this was true of theSecond Templeas well.[26]

Many forms ofJudaisminclude a belief in the existence of angels, including cherubim within theJewish angelic hierarchy.The existence of angels is generally accepted within traditionalrabbinic Judaism.There is, however, a wide range of beliefs within Judaism about what angels actually are and how literally one should interpret biblical passages associated with them.

InKabbalahthere has long been a strong belief in cherubim, the cherubim and other angels regarded as having mystical roles. TheZohar,a highly significant collection of books in Jewish mysticism, states that the cherubim were led by one of their number named Kerubiel.[2]

On the other end of the philosophical spectrum isMaimonides,who had a neo-Aristotelian interpretation of the Bible. Maimonides writes that to the wise man, one sees that what the Bible and Talmud refer to as "angels" are actually allusions to the various laws of nature; they are the principles by which the physical universe operates.

For all forces are angels! How blind, how perniciously blind are the naive?! If you told someone who purports to be a sage of Israel that the Deity sends an angel who enters a woman's womb and there forms an embryo, he would think this a miracle and accept it as a mark of the majesty and power of the Deity, despite the fact that he believes an angel to be a body of fire one third the size of the entire world. All this, he thinks, is possible for God. But if you tell him that God placed in the sperm the power of forming and demarcating these organs, and thatthisis the angel, or that all forms are produced by the Active Intellect; that here is the angel, the "vice-regent of the world" constantly mentioned by the sages, then he will recoil.

For he [the naive person] does not understand that the true majesty and power are in the bringing into being of forces which are active in a thing although they cannot be perceived by the senses... Thus the Sages reveal to the aware that the imaginative faculty is also called an angel; and the mind is called acherub.How beautiful this will appear to the sophisticated mind, and how disturbing to the primitive.

Maimonidessays that the figures of the cherubim were placed in the sanctuary only to preserve among the people the belief in angels, there being two in order that the people might not be led to believe that they were the image of God.[27]

Cherubim are discussed within themidrashliterature. The two cherubim placed byGodat the entrance of paradise[28]were angels created on the third day, and therefore they had no definite shape; appearing either as men or women, or as spirits or angelic beings.[29]The cherubim were the first objects created in the universe.[30]The following sentence of the Midrash is characteristic:

When a man sleeps, the body tells to the soul (neshamah) what it has done during the day; the soul then reports it to the spirit (nefesh), the spirit to the angel, the angel to the cherub, and the cherub to the seraph, who then brings it before God ".[31][32]

In early Jewish tradition there existed the notion that cherubim had youthful, human features, due to the etymologization of the name byAbbahu(3rd century). Before this, some early midrashic literature conceived of the cherubim as non-corporeal. In the first century AD,Josephusclaimed:

No one can tell, or even conjecture, what was the shape of these cherubim.[33][8](p 1)

A midrash states that when Pharaoh pursued Israel at the Red Sea, God took a cherub from the wheels of His throne and flew to the spot, for God inspects the heavenly worlds while sitting on a cherub. The cherub, however, is "something not material", and is carried by God, not vice versa.[33][34][35]

In the passages of theTalmudthat describe the heavens and their inhabitants, the seraphim, ofanim, andliving creaturesare mentioned, but not the cherubim;[36]and the ancient liturgy also mentions only these three classes.

In theTalmud,Jose the Galileanholds[37]that when theBirkat Hamazon(grace after meals) is recited by at least ten thousand seated at one meal, a special blessing

Blessed is Ha-Shem our God, the God of Israel,who dwellsbetween the cherubim

is added tothe regular liturgy.

In Christianity

[edit]

In theBook of Genesis,the Cherubim were introduced:

So he drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.

–Genesis 3:24

They were described further in theBook of Ezekiel:

Each of the cherubim had four faces: One face was that of a cherub, the second the face of a human being, the third the face of a lion, and the fourth the face of an eagle.

–Ezekiel 10:14

In Medievaltheology,following the writings ofPseudo-Dionysius,the cherubim are the second highest rank in theangelic hierarchy,following theseraphimand preceding theThrones.[38]Cherubim are regarded in traditionalChristian angelologyas angels of the second highest order of the ninefold celestial hierarchy.[39]De Coelesti Hierarchia(c. 5th century) lists them alongsideSeraphimandThrones.[3]According toThomas Aquinas,the cherubim are characterized by knowledge, in contrast to seraphim, who are characterized by their "burning love to God".[40]

In Western art, cherubim became associated with theputtoand theGreco-RomangodCupid/Eros,with depictions as small, plump, winged boys.[8](p 1)Artistic representations of cherubim in Early Christian andByzantine artsometimes diverged from scriptural descriptions. The earliest known depiction of thetetramorphcherubim is the 5th–6th century apse mosaic found in theThessalonianChurch of Hosios David.This mosaic is an amalgamation ofEzekiel's visions inEzekiel 1:4–28,Ezekiel 10:12,Isaiah'sseraphiminIsaiah 6:13and the six-winged creatures ofRevelationfromRevelation 4:2–10.[41]

In Islam

[edit]

Al-Karubiyyin,[42]according to the Quran, are identified as a class ofal-muqarrabin,[43]and are a class of angels near the presence of God. They are entrusted with praising God and interceding for humans.[44]They are usually identified either with a class of angels separate or include various angels absorbed in the presence of God: the canonical four Islamic archangelsJibra'il,Mika'il,Azra'el,andIsrafil,the actual cherubim and theBearers of the Throne.[45]

Some scholars had a more precise approach:ibn Kathirdistinguishes between the angels of the throne and the cherubim.[44]In a 13th–14th-century work called "Book of the Wonders of Creation and the peculiarities of Existing Things", the cherubim belong to an order below the Bearers of the Throne, who in turn are identified withseraphiminstead.[46]Abu Ishaq al-Tha'labiplaces the cherubim as the highest angels only next to the Bearers of the Throne.[44]Similarly,Fakhr al-Din al-Razidistinguishes between the angels carrying the throne (seraphim) and the angels around the throne (cherubim).[47]

TheQuranmentions theMuqarrabininAn-Nisaverse 172, angels who worship God and are not proud. Further, cherubim appear inMiraj literature[48]and theQisas al-Anbiya.[49]The cherubim around the throne are continuously praising God with thetasbih:"Glory to God!"[50]They are described as bright as no one of the lower angels can envision them.[51]Cherubim as angels of mercy, created by the tears of Michael, are not identified with the angels in God's presence, but of lower rank. They too, request God to pardon humans.[52]: 33–34 In contrast to the messenger angels, the cherubim (and seraphim) always remain in the presence of God.[44]If they stop praising God, they fall.

TheTwelver Shi'ascholarMohammad-Baqer Majlesinarrates about afallen cherubencountered byMuhammadin the form of a snake. The snake tells him that he did not performdhikr(remembrance of God) for a moment so God was angry with him and cast him down to earth in the form of a snake. Then Muhammad went toHasanandHusayn.Together they interceded (tawassul) for the angel and God restored him to his angelic form.[53]A similar story appears in Tabari'sBishara.An angel calledFutrus,described as an "angel-cherub" (malak al-karubiyyin), was sent by God, but since the angel failed to complete his task in time, God broke one of his wings. Muhammad interceded for the cherub, and God forgave the fallen angel, whereupon he became the guardian forHussain's grave.[54]

See also

[edit]- Buraq

- Cherubism(medical condition)

- Gandharva

- List of angels in theology

- Kamadeva

- Lamassu

- Merkabah mysticism

References

[edit]- ^"cherub".Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^abcdefgh"Cherub".Jewish Encyclopedia.2002–2011 [1906].

- ^abKosior, Wojciech (2013)."The angel in the Hebrew Bible from the statistic and hermeneutic perspectives: Some remarks on the interpolation theory".The Polish Journal of Biblical Research.12(1–2 (23–24)): 55–70.

- ^Husain, O.; Gandhi, M. (2004).The Complete Book of Muslim and Parsi Names.India: Penguin Books. p. 222.

- ^Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall, Joseph(5 March 2016) [1813].Rosenöl. Erstes und zweytes Fläschchen: Sagen und Kunden des Morgenlandes aus arabischen, persischen, und türkischen Quellen gesammelt[Rose Oil. First and second bottle: Legends and customs of the Orient collected from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish sources]. Books on Demand. p. 12.ISBN978-386199486-2.

- ^Netton, Ian Richard (1994).Allah Transcendent: Studies in the structure and semiotics of Islamic philosophy, theology, and cosmology.Psychology Press. p. 205.ISBN9780700702879.

- ^"Ezekiel 1:6-7".Sefaria.

- ^abcdefghijklmWood, Alice (2008).Of Wing and Wheels: A synthetic study of the Biblical cherubim.Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Vol. 385.ISBN978-3-11-020528-2.

- ^"What is a cherub? The cherubim in the Bible".Christianity.Retrieved2021-03-04.

- ^Meyer, M.;Barnstone, W.(June 30, 2009). "The Second Treatise of the Great Seth".The Gnostic Bible.Shambhala.Retrieved2022-02-02.

- ^De Vaux, Roland (tr. John McHugh),Ancient Israel: Its Life and Institutions(New York, McGraw-Hill, 1961).

- ^1 Samuel 4:4, 2 Samuel 6:2, 2 Samuel 22:11

- ^1 Chronicles 13:6.

- ^2 Samuel 22:11.

- ^Psalms 18:10.

- ^abEichler, Raanan (2015). "Cherub: A History of Interpretation".Biblica.96(1): 26–38.JSTOR43922717.

- ^abcWright, G. Ernest (1957).Biblical Archaeology.Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Westminster Press.

- ^Propp, William H. (2006).The Anchor Bible.Vol. 2A, Exodus 19–40. New York, New York: Doubleday. Exodus 15:18, p. 386,Notes.ISBN0-385-24693-5.which referencesWellhausen, Julius(1885).Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels[Prolegomena to the History of Israel] (in German). Edinburgh, Scotland: Black. p. 304.

- ^Beekes, Robert S. P.(2010). "γρυπος".Etymological Dictionary of Greek.Vol. 1. Leiden, DE / Boston, Massachusetts: Brill. p. 289.ISBN978-90-04-17420-7.

From the archaeological perspective, origin in Asia Minor (and the Near East:Elam) is very probable.

- ^"Bible Gateway passage: Genesis 3:24 – King James Version".Bible Gateway.Retrieved2023-11-09.

- ^"1 Kings 6:23–6:35 KJV – And within the oracle he made two".Bible Gateway.Retrieved2012-12-30.

- ^Eichler, Raanan (1 January 2014). "The Meaning of יֹשֵׁב הַכְּרֻבִים".Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft.126(3): 358–371.doi:10.1515/zaw-2014-0022.S2CID170794397.

- ^Wood, Alice.Of Wings and Wheels: A Synthetic Study of the Biblical Cherubim.p. 94.

- ^Wood, Alice.Of Wings and Wheels: A Synthetic Study of the Biblical Cherubim.p. 137.

- ^Babylonian Talmud(Sukkah5b).

- ^"Yoma 54a:17".sefaria.org.Retrieved2021-02-19.

- ^Maimonides,The Guide for the PerplexedIII:45.

- ^Gen. iii. 24.

- ^Genesis Rabbah xxi., end.

- ^Tanna debe Eliyahu R., i. beginning.

- ^Leviticus Rabbah xxii.

- ^Eccl. Rabbah x. 20.

- ^abJosephus.Antiquities of the Jews.8:73.

- ^Midr. Teh. xviii. 15.

- ^Canticles Rabbah i. 9.

- ^Ḥag. 12b.

- ^Berakhot49b.

- ^"Dionysius the Areopagite: Celestial Hierarchy".esoteric.msu.edu.Chapter VII.Retrieved2023-11-09.

- ^"Oxford Dictionaries: cherub".Oxford University Press.2013. Archived fromthe originalon December 13, 2013.

- ^Keck, D. (1998). Angels and Angelology in the Middle Ages. Ukraine: Oxford University Press. p. 25.

- ^Peers, Glenn (2001).Subtle bodies: representing angels in Byzantium.Berkeley, California: University of California press.ISBN978-0-520-22405-6.

- ^Moojan Momen.Studies in Honor of the Late Hasan M. Balyuzi,Kalimat Press 1988,ISBN978-0-933-77072-0.p. 83.

- ^Gallorini, Louise. THE SYMBOLIC FUNCTION OF ANGELS IN THE QURʾĀN AND SUFI LITERATURE. Diss. 2021. p. 125.

- ^abcdSchöck, Cornelia (1996). "Die Träger des Gottesthrones in Koranauslegung und islamischer Überlieferung".Die Welt des Orients.27:104–132.JSTOR25683589.

- ^Wensinck, A. J. (2013). The Muslim Creed: Its Genesis and Historical Development. Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis. p. 200.

- ^Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, New York, Komaroff, L.; Carboni, S. (2002). The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256–1353. Vereinigtes Königreich: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^Serdar, Murat. "Hıristiyanlık ve İslâm’da Meleklerin Varlık ve Kısımları." Bilimname 2009.2 (2009).

- ^Colby, Frederick S (2008).Narrating Muhammad's Night Journey: Tracing the Development of the Ibn 'Abbas Ascension Discourse.State University of New York Press. p. 33.ISBN978-0-7914-7518-8.

- ^Heribert Busse.Islamische Erzählungen von Propheten und Gottesmännern: Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʼ oder ʻArāʼis al-maǧālis.Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006ISBN9783447052665p. 34 (in German).

- ^"Cherub | Definition & Facts | Britannica".Encyclopædia Britannica.13 October 2023.

- ^Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, Volume 1. Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. p. 32.

- ^Qāḍī, ʻAbd al-Raḥīm ibn Aḥmad (1977).Islamic book of the dead: a collection of Hadiths on the Fire & the Garden.Norwich, Norfolk: Diwan Press.ISBN0-9504446-2-6.OCLC13426566.

- ^"Ahlulbait.one – Ahlulbait.one"(in German).Retrieved2023-11-09.

- ^Kohlberg, E. (2020). In Praise of the Few. Studies in Shiʿi Thought and History. Niederlande: Brill. p. 390.

Further reading

[edit]- Gilboa, R. (1996). "Cherubim: An inquiry into an Enigma".Biblische Notizen.82:59–75.The article looks at the yet unknown nature of the Temple's Cherubim, through linguistic investigation, fauna probabilities and artistic presentations in the ancient Biblical period.

- Yaniv, Bracha (1999).The Cherubim on Torah Ark valances.Assaph: Studies in Art History 4.Bar-Ilan University,Jewish Art Department.