Naval history of China

| Part ofa serieson the |

| History of China |

|---|

Thenaval history of Chinadates back thousands of years, with archives existing since the lateSpring and Autumn periodregarding the Chinese navy and the various ship types employed in wars.[1]TheMing dynastyof China was the leading global maritime power between 1400 and 1433, when Chinese shipbuilders builtmassive ocean-going junksand the Chinese imperial court launchedseven maritime voyages.[2]In modern times, the currentPeople's Republic of Chinaand theRepublic of Chinagovernments continue to maintain standing navies through thePeople's Liberation Army Navyand theRepublic of China Navy,respectively.

History

[edit]Early coastal maritime endeavours

[edit]

TheHan dynastyestablished the firstindependent naval forcein China, theTower Ship Navy.

Although naval battles took place before the 12th century, such as the large-scaleThree KingdomsBattle of Chibiin the year 208, it was during theSong dynasty(960–1279) that the Chinese established a permanent, standing navy in 1132.[3]At its height by the late 12th century there were 20squadronsof some 52,000 marines, with the admiral's headquarters atDinghai,while the main base remained closer to modernShanghai.[3]

The establishment of the first permanent Chinese navy by theSouthern Song dynasty[4]came out of the need to defend against theJin dynasty,who had overrun the northern China, and to escort merchant fleets entering the Southeast Pacific andIndian Oceanon long trade missions abroad to theHindu,Islamic,andEast Africanspheres of the world. However, considering variousCentral Plainpolities were for a long time menaced by land-based nomadic tribes such as theXiongnu,Göktürks,KhitansandMongols,the navy was seen as an adjunct rather than an important military force. By the 15–16th centuriesChina's canal systemand internal economy were sufficiently developed to nullify the need for the Pacific fleet, which was scuttled when conservativeConfucianistsgained power in the court and began a policy of introspection. After theFirstandSecond Opium Wars,which shook up the generals of theQing dynasty,the government attached greater importance to the navy.

When the BritishRoyal Navyencountered the Chinese during theFirst Opium War,their officers noted the appearance ofpaddle-wheel boatsamong the Chinese fleet, which they took to be copies of a Western design. They also discovered a nearly-complete 30-gunman-of-warinXiamen,along with new paddle-boats and brass guns under construction inWusongandShanghai.[5]Paddle-wheel boats were actually developed by the Chinese independently in the 5th–6th centuries, only a century after their first surviving mention inRomansources (seePaddle steamer),[6]though that method of propulsion had been abandoned for many centuries and only recently reintroduced before the war. Numerous other innovations were present in Chinese vessels during theMiddle Agesthat had not yet been adopted by theWesternandIslamic worlds,some of which were documented byMarco Polobut were not adopted by other navies until the 18th century, when the British successfully incorporated them into ship designs. For example, medieval Chinese hulls were split intobulkhead sectionsso that a hull rupture only flooded a fraction of the ship and did not necessarily sink it (seeShip floodability). This was described in the book of the Song dynasty maritime authorZhu Yu,thePingzhou Table Talksof 1119 AD.[7]Along with the innovations described in Zhu's book, there were many other improvements to nautical technology in the medieval Song period. These included crossbeams bracing the ribs of ships to strengthen them, rudders that could be raised or lowered to allow ships to travel in a wider range of water depths, and the teeth ofanchorsarranged circularly instead of in one direction, "making them more reliable".[8]Junksalso had their sails staggered by wooden poles so that the crew could raise and lower them with ropes from the deck, like window blinds, without having to climb around and tie or untie various ropes every time the ship needed to turn or adjust speed.

A significant naval battle was theBattle of Lake Poyangfrom August 30 to October 4 of the year 1363 AD during theRed Turban Rebellion,a battle which cemented the success ofZhu Yuanzhangin founding theMing dynasty.

Ming expeditions and decline

[edit]After the period of maritime activity during thetreasure voyagesunder theYongle Emperor,the official policy towards naval expansion swayed between active restriction to ambivalence.[9]

Despite Ming ambivalence towards naval affairs, theChinese treasure fleetwas still able to dominate other Asian navies, which enabled the Ming to send governors to rule in Luzon and Palembang as well as depose and enthrone puppet rulers in Sri Lanka and the Bataks.[10]

However, the Chinese fleet shrank tremendously after its military/tributary/exploratory functions in the early 15th century were deemed too expensive and it became primarily a police force on routes like theGrand Canal.Ships like the juggernauts ofZheng He's "treasure fleet,"which dwarfed the largestPortuguese shipsof the era by several times, were discontinued, and thejunkbecame the predominant Chinese vessel until the country's relatively recent (in terms of Chinese sailing history) naval revival

In 1521, at theBattle of Tunmena squadron of Ming naval junks defeated aPortuguesecaravelfleet, which was followed by another Ming victory against a Portuguese fleet at theBattle of Xicaowanin 1522. In 1633, a Ming navy defeated a Dutch and Chinese pirate fleet during theBattle of Liaoluo Bay.A large number of military treatises, including extensive discussions of naval warfare, were written during the Ming period, including theWubei ZhiandJixiao Xinshu.[11]Additionally, shipwrecks have been excavated in theSouth China Sea,including wrecks of Chinese trade and war ships that sank around 1377 and 1645.[12]

The continuing "sea ban"policy during the early Qing dynasty meant that the development of naval power stagnated. River and coastal naval defence was the responsibility of the waterborne units of theGreen Standard Army,which were based at Jingkou (nowZhen gian g) andHangzhou.

In 1661, a naval unit was established atJilinto defend against Russian incursions intoManchuria.Naval units were also added to variousBannergarrisons subsequently, referred to collectively as the "Eight Banners Navy". In 1677, the Qing court re-established the Fu gian Fleet in order to combat the Ming-loyalistKingdom of Tungningbased onTaiwan.This conflict culminated in the Qing victory theBattle of Penghuin 1683 and the surrender of the Tungning shortly after the battle. TheSecond Opium Warshowed the complete futility of the pre-modern Chinese fleet when facing modern European navies, when 300 Chinese naval junks, armed with British-made guns, did almost no damage to 56 British and Frenchironclads.

In the 1860s, an attempt to establish a modern navy via the British-builtOsborn or "Vampire" Fleetto combat theTaiping rebels' US-built gunboats. The so-called "Vampire Fleet" fitted out by the Chinese government for the suppression ofpiracyon the coast of China, owing to the non-fulfilment of the condition that British commander Sherard Osborn should receive orders from the imperial government only, was scrapped.[13]

Imperial Chinese Navy

[edit]

There were four fleets of theImperial Chinese Navy:

- Beiyang Fleet- North Sea Fleet based fromWeihaiwei

- Nanyang Fleet- South Sea Fleet based fromShanghai

- Guangdong Fleet- based from Canton (nowGuangzhou)

- Fu gian Fleet- based fromFuzhou,founded in 1678 as theFu gian Marine Fleet[14]

In 1865, theJiangnan Shipyardwas established.

In 1874, a Japanese incursion intoTaiwanexposed the vulnerability of China at sea. A proposal was made to establish three modern coastal fleets: the Northern Sea or Beiyang Fleet, to defend theYellow Sea,the Southern Sea or Nanyang Fleet, to defend theEast China Sea,and the Canton Sea or Yueyang Fleet, to defend theTaiwan Straitand theSouth China Sea.The Beiyang Fleet, with a remit to defend the section of coastline closest to the capitalBeijing,was prioritised.

A series of warships were ordered from Britain and Germany in the late 1870s, and naval bases were built atPort ArthurandWeihaiwei.The first British-built ships were delivered in 1881, and the Beiyang Fleet was formally established in 1888. Many children of Chinese military families were sent abroad to study in theUnited Statesin order to modernize the Imperial Chinese Navy, although they were denied admission to the military academies ofWest PointandAnnapolisand had to switch to other countries after the passage of theChinese Exclusion Act.[5]In 1894 the Beiyang Fleet was on paper the strongest navy in Asia at the time. However, it was largely lost during theFirst Sino-Japanese Warafter theBattle of the Yalu River.This battle allowed theImperial Japanese Armyto invade China, occupy theShandong Peninsula,anduse the fortress at Weihaiweito shell the Chinese fleet.[5][15]Although the modern battleshipsZhenyuanandDingyuanwere impervious to Japanese fire, they were unable to sink a single ship and all eight cruisers were lost.[15]The battle displayed once again thatthe modernisation efforts of Chinawere far inferior to theMeiji Restoration.

The Nanyang Fleet was also established in 1875, and grew with mostly domestically built warships and a small number of acquisitions fromBritainandGermany.It fought in theSino-French War,performing somewhat poorly against the French in all engagements and resulting in allowing theFrench colonization of Southeast Asia.The defeat of the Nanyang Fleet also emboldened the British to complete theirannexation of Burmain theThird Anglo-Burmese War.[citation needed]

The separateFu gianandGuangdongfleets became part of the Imperial navy after 1875. TheFu gian Fleetwas almost annihilated during the Sino-French War, and was only able to acquire two new ships thereafter. By 1891, due to budget cuts, the Fu gian Fleet was barely a viable fleet. Due to corruption much of the funds needed by the navy was taken by theDowager Empress Cixito renovate theSummer Palaceand build herMarble Boat.[5]TheGuangdong Fleetwas established in the late 1860s and based atWhampoa,in Canton (nowGuangzhou). Ships from the Guangdong Fleet toured the South China Sea in 1909 as a demonstration of Chinese control over the sea.

After the First Sino-Japanese War,Zhang Zhidongestablished ariver-based fleetinHubei.

In 1909, the remnants of the Beiyang, Nanyang, Guangdong and Fu gian Fleets, together with the Hubei fleet, were merged, and re-organised as the Sea Fleet and the River Fleet.

In 1911,Sa Zhenbingbecame the Minister of Navy of theGreat Qing.

One of the new ships delivered after the war with Japan, thecruiserHai Chi,in 1911 became the first vessel flying theYellow Dragon Flagto arrive in American waters, visitingNew York Cityas part of a tour.[16][17][18][19]

Modern

[edit]

TheRepublic of China Navyis the navy of theRepublic of China,which was established after theoverthrow of the Qing dynasty.Liu Guanxiong,a former Qing dynasty admiral, became the first Minister of Navy of the Republic of China. During theWarlord Erathat scarred China in the 1920s and 1930s the ROCN remained loyal to theKuomintanggovernment ofSun Yat-seninstead of theBeiyang governmentinBeijingwhich fell to theNationalist governmentin the 1928Northern Expeditionand between the civil war with theCommunist Partyand1937 Japanese invasion of Northeast China.During that time and throughoutWorld War II,the ROCN concentrated mainly on riverine warfare as the poorly equipped ROCN was not a match toImperial Japanese Navyover ocean or coast.[20]The ROCN is currently the naval forces on the island ofTaiwan.

ThePeople's Liberation Army Navywas established in 1950 for thePeople's Republic of China.The PLAN can trace its lineage to naval units fighting during theChinese Civil Warand was established in September 1950. The PLAN was initially dedicated to coastal defense, defending against commando raids on theFu giancoast fromTaiwan.It also played a role in theFirstandSecond Taiwan Strait Crises.[5]

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, theSoviet Unionprovided assistance to the PLAN in the form of naval advisers and export of equipment and technology.[21]This assistance ended after theSino-Soviet split.[5]Until the late 1980s, the PLAN remained largely ariverineandlittoralforce (brown-water navy). However, by the 1990s, following thefall of the Soviet Unionand a shift towards a more forward-oriented foreign and security policy, the leaders of the Chinese military were freed from worrying over land border disputes, and instead turned their attention towards the seas. This led to the development of the People's Liberation Army Navy into agreen-water navyby 2009.[22]Before the 1990s the PLAN had traditionally played a subordinate role to thePeople's Liberation Army Ground Force.

In 2020 the PLAN surpassed theU.S. Navyas the largest navy in the world in numbers of ships, although the U.S. Navy continued to have technological advantages. This development occurred amidincreasing tensions between China and the United Statesand as China was becoming involved interritorial disputes in the South China Sea.[23]

Literature

[edit]Early literature

[edit]

One of the oldest known Chinese books written on naval matters was theYuejueshu(Lost Records of theState of Yue) of 52 AD, attributed to theHan dynastyscholar Yuan Kang.[1]Many passages of Yuan Kang's book were rewritten and published inLi Fang'sImperial Reader of the Taiping Era,compiled in AD 983.[24]The preserved written passages of Yuan Kang's book were again featured in theYuan gian Leihan(Mirror of the Infinite, a Classified Treasure Chest) encyclopedia, edited and compiled by Zhang Ying in 1701 during theQing dynasty.[1]

Yuan Kang's book listed various water crafts that were used for war, including one that was used primarily forramminglikePhoeniciantriremes.[25]These "classes" of ships were the great wing (da yi), the little wing (xiao yi), the stomach striker (tu wei), thecastleship (lou chuan), and the bridge ship (qiao chuan).[1]These were listed in theYuejueshuas a written dialogue betweenKing Helü of Wu(r. 514 BC–496 BC) andWu Zixu(526 BC–484 BC). TheWu Kingdom'sNavy is regarded as the origin of the first Chinese Navy which consisted of different ships for specific purposes. Wu Zixu stated:

Nowadays in training naval forces we use the tactics of land forces for the best effect. Thus great wing ships correspond to the army's heavychariots,little wing ships to light chariots, stomach strikers tobattering rams,castle ships tomobile assault towers,and bridge ships to lightcavalry.[1]

Ramming vessels were also attested to in other Chinese documents, including theShi Mingdictionary of c. 100 AD written by Liu Xi.[26]The Chinese also used a large iron t-shapedhookconnected to asparto pin retreating ships down, as described in theMozibook compiled in the 4th century BC.[27]This was discussed in a dialogue between Mozi andLu Banin 445 BC (when Lu traveled to theState of Chufrom theState of Lu), as the hook-and-spar technique made standard on all Chuwarshipswas given as the reason why the Yue navy lost in battle to Chu.[28]

The rebellion ofGongsun ShuinSichuanprovince against the re-established Han dynasty during the year 33 AD was recorded in theBook of Later Han,compiled byFan Yein the 5th century.[25]Gongsun sent a naval force of some twenty to thirty thousand soldiers down theYangtzeRiver to attack the position of the Han commander Cen Peng.[29]After Cen Peng defeated several of Gongsun's officers, Gongsun had a long floatingpontoon bridgeconstructedacross the Yangtzewith fortified posts on it, protected further by a boom, as well as erecting forts on the river bank to provide further missile fire at another angle.[26]Cen Peng was unable to break through this barrier and barrage of missile fire, until he equipped his navy with castle ships, rowed assault vessels, and 'colliding swoopers' used for ramming in a fleet of several thousand vessels and quelled Gongsun's rebellion.[26]

The 'castle ship' design described by Yuan Kang saw continued use in Chinese naval battles after the Han period. Confronting the navy of theChen dynastyon theYangtzeRiver,Emperor Wen of Sui(r. 581–604) employed an enormous naval force of thousands of ships and 518,000 soldiers stationed along the Yangtze (fromSichuanto thePacific Ocean).[30]The largest of these ships had five layered decks, could hold 800 passengers, and each ship was fitted with six 50 ft. longboomsthat were used to swing and damage enemy ships, along with the ability of pinning them down.[30]

Vessels of the Tang dynasty

[edit]During the ChineseTang dynasty(618–907 AD) there were some famous naval engagements, such as the Tang-Sillavictory over the Korean kingdom ofBaekjeandYamatoJapanese forces in theBattle of Baekgangin 663. Tang dynasty literature on naval warfare and ship design became more nuanced and complex. In hisTaipai Yinjing(Canon of the White and Gloomy Planet of War) of 759 AD,Li Quangave descriptions for several types of naval ships in his day (note: multiple-deck castle ships are referred to as tower ships below).[31]Not represented here are thepaddle-wheel craftsinnovated by the Tang PrinceLi Gaomore than a decade later in 784 AD.[6]Paddle-wheel craft would continue to hold an important place in the Chinese navy. Along withgunpowderbombs, paddle-wheel craft were a significant reason for the success in the later Song dynasty naval victory of theBattle of Caishiin the year 1161 AD during theJin–Song wars.[32]

Covered swoopers

[edit]Covered swoopers(Meng chong, mông hướng ); these are ships which have their backs roofed over and (armored with) a covering ofrhinoceroshide. Both sides of the ship haveoar-ports; and also bothfore and aft,as well as toportandstarboard,there are openings for crossbows and holes for spears. Enemy parties cannot board (these ships), nor can arrows or stones injure them. This arrangement is not adopted for large vessels because higher speed and mobility are preferable, in order to be able to swoop suddenly on the unprepared enemy. Thus these (covered swoopers) are not fighting ships (in the ordinary sense).[33]

Combat junks

[edit]Combat junks(Zhan xian); combat junks haverampartsand half-ramparts above the side of thehull,with the oar-ports below. Five feet from the edge of the deck (to port and starboard) there is set adeckhousewith ramparts, having ramparts above it as well. This doubles the space available for fighting. There is no cover or roof over the top (of the ship). Serrated pennants are flown from staffs fixed at many places on board, and there aregongsanddrums;thus these (combat junks) are (real) fighting ships (in the ordinary sense).[33]

Flying barques

[edit]Flying barques(Zou ge); another kind of fighting ship. They have a double row of ramparts on the deck, and they carry moresailors(lit. rowers) and fewersoldiers,but the latter are selected from the best and bravest. These ships rush back and forth (over the waves) as if flying, and can attack an enemy unawares. They are most useful for emergencies and urgent duty.[33]

Patrol boats

[edit]Patrol boats(Yu ting) are small vessels used for collectingintelligence.They have no ramparts above the hull, but to port and starboard there is onerowlockevery four feet, varying in total number according to the size of the boat. Whether going forward, stopping, or returning, or making evolutions in formation, the speed (of these boats) is like flying. But they are forreconnaissance,they are not fighting boats/ships.[33]

Sea hawks

[edit]Sea hawks (Hai hu); these ships have lowbowsand highsterns,the forward parts (of the hull) being small and the after parts large, like the shape of thehubird(when floating on the water). Below deck level, both to port and starboard, there are 'floating-boards' (fou ban) shaped like the wings of thehubird. These help the (sea hawk) ships, so that even when wind and wave arise in fury, they are neither (driven) sideways, noroverturn.Covering over and protecting the upper parts on both sides of the ship are stretched rawox-hides, as if on acity wall[afootnote: protection againstincendiaryprojectiles]. There areserratedpennants,and gongs and drums, just as on the fighting ships.[34]

Ships from the Wujing Zongyao

[edit]-

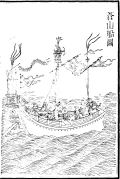

A "tower" ship with a traction-trebucheton its top deck, from theWujing Zongyao

-

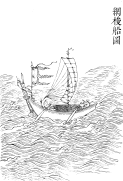

A "combat" ship from theWujing Zongyao

-

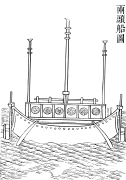

A "covered assault" ship from theWujing Zongyao

-

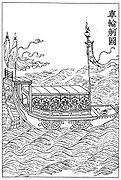

A "flying" barque from theWujing Zongyao

-

A "patrol" boat from theWujing Zongyao

-

A "sea hawk" ship from theWujing Zongyao

-

Chinese fire ships from theWujing Zongyao

Naval endeavours by era

[edit]

- 111 BCE, the delegates ofEmperor Wu of Hanexplored Southeast Asia and India from theGulf of Tonkinto make contact with central Asia states, theSilk Roadof the Sea.

- Rebellion of Gongsun Shu

- Battle of Jiangxia

- Battle of Red Cliffs

- Battle of Ruxu (217)

- Battle of Lake Poyang

- Ming treasure voyagesled byZheng He

- Wokou

- Imjin War

- First Battle of Tamao

- Second Battle of Tamao

- Battle of Penghu (1624)

- Battle of Liaoluo Bay

- Siege of Fort Zeelandia

The Qing established a sea defence force of 7 fleets across 4 sea zones. Due to rebellions in the late 18th century the navy was neglected and declined, ultimately suffering defeat in theOpium Wars.

The modernImperial Chinese Navywas established in 1875, prompted by a Japanese incursion intoTaiwanthat exposed the vulnerability of the existing, pre-modern Chinese navy. Numerous modern ships equipped withKruppguns, electricity, gatling guns,torpedoes,and other modern weapons were acquired by the Qing dynasty from western powers. They were manned by western trained Chinese officers.[35]

- Zheng Chengong

- Battle of Penghu

- Beiyang Fleet

- Nanyang Fleet

- Fu gian Fleet

- Guangdong Fleet

- FirstandSecond Opium Wars

- Sino-French War

- First Sino-Japanese War

- Republic of China Navy

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Battle of Wuhan

- Landing Operation on Hainan Island

- First Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Third Taiwan Strait Crisis

- People's Liberation Army Navy

- First Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Battle of the Paracel Islands

- Third Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Spratly Island Skirmish (1988)

Chinese naval warfare gallery

[edit]-

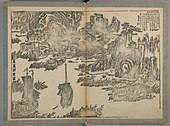

A restored copy of the illustration of Zheng He's visits to the West on the flyleaf of the book "Heavenly Princess Classics" in 1420. This invaluable picture is the earliest pictorial record of Zheng He treasure-ships.

-

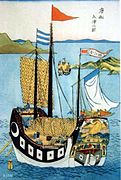

Sketch of Cheng Ho's ship

-

Ships of the world as depicted in theFra Mauro map,1460.

-

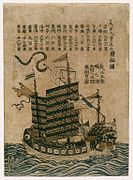

Ming dynasty war junk from Zheng Ruozeng'sChouhai tubian(1562)

-

River ships inTaiping Shanshui tubyXiao Yuncong(1596-1673)

-

A two-masted Chinese junk, from theTiangong KaiwuofSong Ying xing,published in 1637

-

A Ming junk, 1637.

-

Early 17th-century Chinesewoodblockprint, thought to represent Zheng He's ships

-

A Chinese junk in Japan, at the beginning of theSakokuperiod (1644–1648 Japanese woodblock print)

-

Ming-Qing ship (Feng Zhou) from theLiuqiu guozhi lüe(The History of the Ryukyu Kingdom), 1759.

-

Barge,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Covered swooper,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Walking barge,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Fighting ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Sea falcon ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Guangdong ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Xinhui sharp tail ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Dongguan great head ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Great fortune ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Grass ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Haicang ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Wave breaking ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

High branch ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Sound ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Leather bridge ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Cangshan ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Eight oar ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Falcon ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Fishing ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Netting ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Two headed ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Sand ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Beak ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Son and mother boat,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Wheel barge,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Red dragon boat,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Fire ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Bomb laying boat,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Tower ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

JunkKeyingtravelled from China to the United States and England between 1846 and 1848.

-

Chinese ship, 1853.

-

Chinese gunboatCedian,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese ironcladZhenyuan,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese ironcladDingyuan,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserZhiyuan,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserHai Chi,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserHai Tien,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserJingyuan( tĩnh xa ), of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserJingyuan( kinh xa ), of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserLaiyuan,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserChaoyong,of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese coastal defence shipZhongshan,of theRepublic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserChao Ho,of the Republic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserYing Rui,of the Republic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserNing Hai,of the Republic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiserPing Hai,of the Republic of China Navy.

-

A modern replica of the Chinese ironcladDingyuan,as amuseum ship.

-

Restored Chinese coastal defence shipZhongshan,as a museum ship in the Zhongshan Warship Museum.

See also

[edit]- Military history of China before 1912

- Military history of China after 1911:PLA,ROCA

- History of canals in China

- Historyandtechnology of the Song dynasty

- Chinese exploration

- Imperial Chinese Navy

- Sailors in Ming China

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abcdeNeedham, Volume 4, Part 3, 678.

- ^China in History — From 200 to 2005Archived2009-12-12 at theWayback Machine

- ^abNeedham, Volume 4, Part 3, 476.

- ^Ma, Xinru; Kang, David C. (2024).Beyond Power Transitions: The Lessons of East Asian History and the Future of U.S.-China Relations.Columbia Studies in International Order and Politics. New York:Columbia University Press.p. 78.ISBN978-0-231-55597-5.

- ^abcdefSpence, Jonathan D.(1991).The search for modern China(First Norton Paperback ed.). New York, NY.ISBN0-393-30780-8.OCLC24536360.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)-Entry atWorldCat - ^abNeedham, Volume 4, Part 3, 31.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 463.

- ^Graff, 86.

- ^Sim 2017,p. 236.

- ^Papelitzky 2017,p. 130.

- ^Papelitzky 2017,p. 132.

- ^Clowes, Sir William Laird(1903)."SHERARD OSBORN'S CHINESE FLEET".The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Death of Queen Victoria.Vol. 7. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. pp. 171–172.

- ^Li, Guotong (Sep 8, 2016).Migrating Fu gian ese: Ethnic, Family, and Gender Identities in an Early Modern Maritime World.BRILL. p. 71.ISBN9789004327214.

- ^abMark Peattie, David C. Evans (1997).Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy.United States: Naval Institute Press. p. 44.ISBN9780870211928.

- ^"Flag, Pearl & Peace".Time magazine.July 17, 1933. Archived fromthe originalon November 22, 2010.Retrieved2010-12-18.

The cruiser Hai Chi ( "Flag of the Sea" ) earned in 1911 the distinction of being the first Chinese war boat ever to visit the West when she steamed as near as possible to the Coronation of King George V, discharged a cargo of Chinese emissaries in gorgeous silken robes. Built in 1897 the Hai Chi and the equally venerableHai Shen( "Pearl of the Sea" ) were still listed last week as the only cruisers in China's Northeastern Squadron.

- ^"Chinese Cruiser Welcomed To Port. First Ship Flying the Yellow Dragon Flag to Anchor in American Waters".New York Times.September 11, 1911.Retrieved2010-12-18.

Who cruiser Hai-Chi of the Imperial Navy of China, the first vessel of any kind flying the yellow dragon flag of China that has ever been in American waters, steamed into the Hudson yesterday morning and anchored in midstream opposite the Soldiers and Sailors' Monument, at Eighty-ninth Street.

- ^"Men Of Chinese Cruiser Hai-Chi Are Entertained".Christian Science Monitor.September 12, 1911. Archived fromthe originalon November 4, 2012.Retrieved2010-12-18.

Officers and men of the Chinese cruiser Hai-Chi, which arrived at this port Monday, are to be given ample opportunity to see New York during their stay of 10 days here....

- ^New York Tribune September 12,1911

- ^"Lịch sử truyền thừa (History)".ROC Navy.Retrieved2006-03-08.[dead link]

- ^Pike, John."People's Liberation Army Navy – History".Retrieved25 December2014.

- ^Welle ( dw ), Deutsche."China has the world's largest navy — what now for the US? | DW | 21.10.2020".DW.COM.Retrieved2021-10-06.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 678, F.

- ^abNeedham, Volume 4, Part 3, 679.

- ^abcNeedham, Volume 4, Part 3, 680.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 681.

- ^Needham, Volume 3, Part 4, 681-682.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 679-680.

- ^abEbrey, 89.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 685-687.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 421–422.

- ^abcdNeedham, Volume 4, Part 3, 686.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 686-687.

- ^Richard N. J. Wright (2000).The Chinese steam navy 1862-1945.Naval Institute Press. p. 76.ISBN1-86176-144-9.RetrievedFebruary 19,2011.

Sources

[edit]- Cole, Bernard D. (2010).The Great Wall at Sea: China's Navy in the Twenty-First Century(2nd ed.).

- Dewan, Sandeep (2012).China's Maritime Ambitions and the PLA Navy.Vij Books.ISBN9789382573227.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006).East Asia: A Social, Cultural, and Political History.Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.ISBN0-618-13384-4.

- Fisher, Richard (2010).China's Military Modernization: Building for Regional and Global Reach.pp.excerpt and text search.

- Graff, David Andrew; Higham, Robin (2002).A Military History of China.Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

- Lo, Jung-Pang (1955). "The Emergence of China as a Sea Power During the Late Sung and Early Yuan Periods".Far Eastern Quarterly.4.

- Needham, Joseph(1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics.Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Wortzel, Larry;Higham, Robin D. S. (1999).Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese Military History.ABC-CLIO.ISBN9780313293375.

- Yoshihara, Toshi; Holmes, James R., eds. (2010).Red Star over the Pacific: China's Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy.p.excerpt and text search.

- Zheng, Yangwen (2011-10-14).China on the Sea: How the Maritime World Shaped Modern China.BRILL.ISBN978-90-04-19477-9.

- Zurndorfer, Harriet (2016)."Oceans of history, seas of change: recent revisionist writing in western languages about China and East Asian maritime history during the period 1500–1630".International Journal of Asian Studies.13(1): 61–94.doi:10.1017/S1479591415000194.S2CID147906963.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.Country Studies.Federal Research Division.[1]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.Country Studies.Federal Research Division.[1]