Cloaca

Acloaca(/kloʊˈeɪkə/kloh-AY-kə),pl.:cloacae(/kloʊˈeɪsi/kloh-AY-seeor/kloʊˈeɪki/kloh-AY-kee), is the rearorificethat serves as the only opening for thedigestive,reproductive,andurinary tracts(if present) of manyvertebrateanimals. Allamphibians,reptiles,birds,and a few mammals (monotremes,tenrecs,golden moles,andmarsupial moles) have this orifice, from which they excrete bothurineandfeces;this is in contrast to mostplacentalmammals, which have two or three separate orifices for evacuation and reproduction.Excretoryopenings with analogous purpose in someinvertebratesare also sometimes called cloacae. Mating through the cloaca is called cloacalcopulationand cloacal kissing.

The cloacal region is also often associated with a secretory organ, the cloacal gland, which has been implicated in the scent-marking behavior of some reptiles,[1]marsupials,[2]amphibians, andmonotremes.[3]

Etymology

[edit]The word is from theLatinverbcluo,"(I) cleanse", thus the nouncloaca,"sewer,drain ".[4][5][6]

Birds

[edit]

Birds reproduce using their cloaca; this occurs during a cloacal kiss in most birds.[7]Birds that mate using this method touch their cloacae together, in some species for only a few seconds, sufficient time forspermto be transferred from the male to the female.[8]For some birds, such asostriches,cassowaries,kiwi,geese,and some species ofswansandducks,the males do not use the cloaca for reproduction, but have aphallus.[9]

One study[10]has looked into birds that use their cloaca for cooling.[11]

The cloaca in birds may also be referred to as the vent. Amongfalconers,the word vent is also a verb meaning "to defecate".

Fish

[edit]Among fish, a true cloaca is present only inelasmobranchs(sharks and rays) andlobe-finned fishes.Inlampreysand in someray-finned fishes,part of the cloaca remains in the adult to receive the urinary and reproductive ducts, although the anus always opens separately. Inchimaerasand mostteleosts,however, all three openings are entirely separated.[12]

Mammals

[edit]With a few exceptions noted below, mammals have no cloaca. Even in the marsupials that have one, the cloaca is partially subdivided into separate regions for theanusandurethra.

Monotremes

[edit]Themonotremes(egg-laying mammals) possess a true cloaca.[14]

Marsupials

[edit]

Inmarsupials,the genital tract is separate from the anus, but a trace of the original cloaca does remain externally.[12]This is one of the features of marsupials (and monotremes) that suggest their basal nature, as theamniotesfrom which mammals evolved had a cloaca, and probably so did the earliestmammals.

Unlike other marsupials,marsupial moleshave a true cloaca.[15]This fact has been used to argue that they are not marsupials.[16][17][unreliable source?]

Placentals

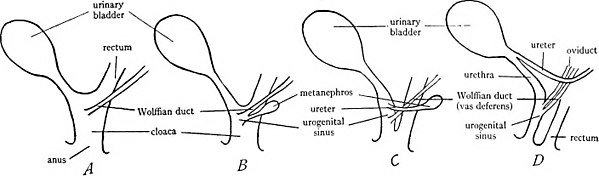

[edit]Most adultplacental mammalshave no cloaca. In the embryo, theembryonic cloacadivides into a posterior region that becomes part of the anus, and an anterior region that develops depending on sex: in males, it forms thepenile urethra,while in females, it develops into thevestibuleorurogenital sinusthat receives the urethra and vagina.[12][18]However, some placental mammals retain a cloaca as adults: those are thetenrecsandgolden moles(small mammals native to Africa), as well as someshrews.[19]

Being placental animals, humans have an embryonic cloaca which divides into separate tracts during thedevelopment of the urinary and reproductive organs.However, a few humancongenital disordersresult in persons being born with a cloaca, includingpersistent cloacaandsirenomelia(mermaid syndrome).

Reptiles

[edit]In reptiles, the cloaca consists of theurodeum,proctodeum,andcoprodeum.[20][21]Some species have modified cloacae for increased gas exchange (seereptile respirationandreptile reproduction). This is where reproductive activity occurs.[22]

Cloacal respiration in animals

[edit]Someturtles,especially those specialized in diving, are highly reliant on cloacalrespirationduring dives.[23]They accomplish this by having a pair of accessory air bladders connected to the cloaca, which can absorb oxygen from the water.[24]

Sea cucumbersuse cloacal respiration. The constant flow of water through it has allowed variousfish,polychaeteworms and evencrabsto specialize to take advantage of it while living protected inside the cucumber. At night, many of these species emerge through the anus of the sea cucumber in search of food.[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Carl Gans; David Crews (June 1992).Hormones, Brain, and Behavior.University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-28124-7.

- ^R. F. Ewer (11 December 2013).Ethology of Mammals.Springer.ISBN978-1-4899-4656-0.

- ^Harris, R. L.,Cameron, E. Z.,Davies, N. W., & Nicol, S. C. (2016).Chemical cues, hibernation and reproduction in female short-beaked echidnas(Tachyglossus aculeatus setosus): implications for sexual conflict. In Chemical Signals in Vertebrates 13 (pp. 145-166). Springer, Cham.

- ^Cassell's Latin Dictionary, Marchant, J.R.V, & Charles, Joseph F., (Eds.), Revised Edition, 1928, p.103

- ^Harper, Douglas."cloaca".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^cloaca.Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short.A Latin DictionaryonPerseus Project.

- ^Michael L. Morrison; Amanda D. Rodewald; Gary Voelker; Melanie R. Colón; Jonathan F. Prather (3 September 2018).Ornithology: Foundation, Analysis, and Application.JHU Press.ISBN978-1-4214-2471-2.

- ^Lynch, Wayne (2007)."The Cloacal Kiss".Owls of the United States and Canada.JHU Press. p. 151.ISBN978-0-8018-8687-4.

- ^Julian Lombardi (1998).Comparative Vertebrate Reproduction.Springer.ISBN978-0-7923-8336-9.Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2014.Retrieved5 December2012.

- ^Hoffman, Ty C. M.; Walsberg, Glenn E.; DeNardo, Dale F. (2007)."Cloacal evaporation: an important and previously undescribed mechanism for avian thermoregulation".The Journal of Experimental Biology.210(5): 741–9.doi:10.1242/jeb.02705.PMID17297135.

- ^Hager, Yfke (2007)."Cloacal Cooling".The Journal of Experimental Biology.210(5): i.doi:10.1242/jeb.02737.

- ^abcRomer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977).The Vertebrate Body.Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 396–399.ISBN978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^Libbie Henrietta Hyman,A laboratory manual for comparative vertebrate anatomy.1922 (1920s)

- ^Mervyn Griffiths (2 December 2012).The Biology of the Monotremes.Elsevier Science.ISBN978-0-323-15331-7.

- ^Gadow, Hans (20 August 2009)."On the Systematic Position of Notoryctes typhlops".Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London.60(3): 361–433.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1892.tb06835.x.

- ^Riedelsheimer, B.; Unterberger, Pia; Künzle, H.; Welsch, U. (November 2007). "Histological study of the cloacal region and associated structures in the hedgehog tenrec Echinops telfairi".Mammalian Biology.72(6): 330–341.Bibcode:2007MamBi..72..330R.doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2006.10.012.

- ^Chimento, Nicolás; Agnolin, Federico (22 December 2014),Morphological evidence supports Dryolestoid affinities for the living Australian marsupial mole Notoryctes,PeerJ PrePrints,doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.755

- ^Linzey, Donald W. (2020).Vertebrate Biology: Systematics, Taxonomy, Natural History, and Conservation.Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 306.ISBN978-1-42143-733-0.

- ^Symonds, Matthew R. E. (February 2005). "Phylogeny and life histories of the 'Insectivora': controversies and consequences".Biological Reviews.80(1): 93–128.doi:10.1017/S1464793104006566.PMID15727040.S2CID21132866.

- ^Stephen J. Divers; Douglas R. Mader (13 December 2005).Reptile Medicine and Surgery - E-Book.Elsevier Health Sciences.ISBN978-1-4160-6477-0.

- ^C. Edward Stevens; Ian D. Hume (25 November 2004).Comparative Physiology of the Vertebrate Digestive System.Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–.ISBN978-0-521-61714-7.

- ^Orenstein, Ronald (2001).Turtles, Tortoises & Terrapins: Survivors in Armor.Firefly Books.ISBN978-1-55209-605-5.

- ^Dunson, William A. (1960). "Aquatic Respiration in Trionyx spinifer asper".Herpetologica.16(4): 277–83.JSTOR3889486.

- ^The Straight Dope - Is it true turtles breathe through their butts?

- ^Aquarium Invertebrates by Rob Toonen, Ph.D.