Cluj-Napoca

Cluj-Napoca | |

|---|---|

From top and left: Cluj-Napoca panorama •St. Michael's Church•Dormition of the Theotokos Cathedral•Medieval house of Matthias Corvinus•Romanian National Opera•Babeș-Bolyai University | |

| Nickname(s): | |

Location in Cluj County | |

| Coordinates:46°46′N23°35′E/ 46.767°N 23.583°E | |

| Country | Romania |

| County | Cluj County |

| Status | County seat |

| Attested | 1213 (first official record asClus) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor(2020–2024) | Emil Boc[3](PNL) |

| • Deputy Mayor | Dan Tarcea (PNL) |

| • Deputy Mayor | Emese Oláh (UDMR) |

| • City Manager | Gheorghe Șurubaru (PNL) |

| Area | |

| •City | 179.5 km2(69.3 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,537.5 km2(593.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 340 m (1,120 ft) |

| Population | |

| •City | 286,598 |

| • Density | 1,597/km2(4,140/sq mi) |

| •Metro (2011) | 411,379[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+2(EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3(EEST) |

| Postal Code | 400xyz1 |

| Area code | +40 x642 |

| Car Plates | CJ3 |

| Website | primariaclujnapoca |

| 1x, y, and z are digits that indicate the street, part of the street, or even the building of the address 2x is a digit indicating the operator: 2 for the former national operator,Romtelecom,and 3 for the other ground telephone networks 3used just on the plates of vehicles that operate only within the city limits (such astrolley buses,trams,utility vehicles,ATVs,etc.) | |

Cluj-Napoca(Romanian:[ˈkluʒnaˈpoka]), or simplyCluj(Hungarian:Kolozsvár[ˈkoloʒvaːr],German:Klausenburg), is the second-most populous city inRomania[5]and the seat ofCluj Countyin the northwestern part of the country. Geographically, it is roughly equidistant fromBucharest(445 kilometres (277 miles)),Budapest(461 km (286 mi)) andBelgrade(483 km (300 mi)). Located in theSomeșul Micriver valley, the city is considered the unofficial capital of thehistorical provinceofTransylvania.For some decades prior to theAustro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867,it was the official capital of theGrand Principality of Transylvania.

As of 2021[update],286,598 inhabitants live in the city (making it the country's secondmost populousat the time, after the national capital Bucharest).[5]TheCluj-Napoca metropolitan areahad a population of 411,379 people,[4][6]while the population of theperi-urbanarea (Romanian:zona periurbană) is approximately 420,000.[4][7]The new metropolitan government of Cluj-Napoca became operational in December 2008.[8]According to a 2007 estimate provided by the County Population Register Service, the city hosts a visible population of students and other non-residents, an average of over 20,000 people each year during 2004–2007.[9]The city spreads out fromSt. Michael's ChurchinUnirii Square,built in the 14th century and named afterthe Archangel Michael,Cluj'spatron saint.[10]The municipality covers an area of 179.52 square kilometres (69.31 sq mi).

Cluj experienced a decade of decline during the 1990s, its international reputation suffering from the policies of its mayor at the time,Gheorghe Funar.[11]Today, the city is one of the most important academic, cultural, industrial and business centres in Romania. Among other institutions, it hosts the country's largest university,Babeș-Bolyai University,with itsbotanical garden;nationally renowned cultural institutions; as well as the largest Romanian-owned commercial bank.[12][13]Cluj-Napoca held the titles ofEuropean Youth Capitalin 2015,[14]and European City of Sport in 2018.[15]In 2021, the city joined theUNESCOCreative Cities Networkand was named a UNESCOCity of Film.[16]

Etymology[edit]

Napoca[edit]

On the site of the city was apre-Roman settlementnamedNapoca.After the AD 106Roman conquest of the area,the place was known asMunicipium Aelium Hadrianum Napoca.Possible etymologies forNapocaorNapucainclude the names of someDacian tribessuch as theNaparisorNapaei,the Greek termnapos(νάπος), meaning "timbered valley" or theIndo-European root*snā-p-(Pokorny971–972), "to flow, to swim, damp".[17]

Cluj[edit]

The first written mention of the city's current name – as a Royal Borough – was in 1213 under theMedieval LatinnameCastrum Clus.[18]Despite the fact thatClusas a county name was recorded in the 1173 documentThomas comes Clusiensis,[19]it is believed that the county's designation derives from the name of thecastrum,which might have existed prior to its first mention in 1213, and not vice versa.[19]With respect to the name of this camp, there are several hypotheses about its origin. It may represent a derivation from theLatintermclausa – clusa,meaning "closed place", "strait", "ravine".[19]Similar meanings are attributed to theSlavic termkluč,meaning "akey"[19]and the GermanKlause – Kluse(meaning "mountain pass" or "weir").[20]The Latin and Slavic names have been attributed to the valley that narrows or closes between hills just to the west ofCluj-Mănăștur.[19]An alternative proposal relates the name of the city to its first magistrate,Miklus–Miklós/Kolos.[20]

TheHungarian formKolozsvár,first recorded in 1246 asKulusuar,underwent variousphonetic changesover the years (uar/vármeans "castle" in Hungarian); the variantKoloswarfirst appears in a document from 1332.[21]ItsSaxonnameClusenburg/Clusenbvrgappeared in 1348, but from 1408 the formClausenburgwas used.[21]TheRomanian nameof the city used to be spelled alternately asClujorCluș,[22]the latter being the case inMihai Eminescu'sPoesis.

Other historical names for the city, all related to or derived from "Cluj" in different languages, includeLatinClaudiopolis,ItalianClausemburgo,[23]TurkishKaloşvar[24]andYiddishקלויזנבורגKloyznburgor קלאזיןKlazin.[22]

Current official name[edit]

Napoca, the pre-Roman and Roman name of ancient settlements in the area of the modern city, was added to the historical and modern name of Cluj duringNicolae Ceaușescu's national-communist dictatorship as part of his myth-making efforts.[25]This happened in 1974, when thecommunist authoritiesmade this nationalist gesture with the goal of emphasising the city's pre-Roman roots.[26][27]The full name of "Cluj-Napoca" is rarely used outside of official contexts.[28]

Nickname[edit]

The nickname "treasure city" was acquired in the late 16th century, and refers to the wealth amassed by residents, including in the precious metals trade.[29]The phrase iskincses városin Hungarian,[2][30]given in Romanian asorașul comoară.[1]

History[edit]

Roman Empire[edit]

TheRoman EmpireconqueredDaciain AD 101 and 106, during the rule ofTrajan,and the Roman settlement Napoca, established about 106, is first recorded on amilestonediscovered in 1758 in the vicinity of the city.[32]Trajan's successorHadriangranted Napoca the status ofmunicipiumasmunicipium Aelium Hadrianum Napocenses.Later, in the second century AD,[33]the city gained the status of acoloniaasColonia Aurelia Napoca.Napoca became a provincial capital ofDacia Porolissensisand thus the seat of aprocurator.Thecoloniawas evacuated in 274 by the Romans.[32]There are no references to urban settlement on the site for the better part of a millennium thereafter.[34]

Middle Ages[edit]

Kingdom of Hungary1000–1526

Eastern Hungarian Kingdom1526–1570

Principality of Transylvania1570–1804

Austrian Empire1804–1867

Austria-Hungary1867–1918(de jureHungaryuntil 1920)

Kingdom of Romania1920–1940(de factofrom 1918to 1940)

Kingdom of Hungary1940–1945

Kingdom of Romania1945–1947

Romanian People's Republic1947–1965

Socialist Republic of Romania1965–1989

Romania1989–present

At the beginning of theMiddle Ages,two groups of buildings existed on the current site of the city: the wooden fortress atCluj-Mănăștur(Kolozsmonostor) and the civilian settlement developed around the currentPiața Muzeului(Museum Place) in the city centre.[19][35]Although the precise date of the conquest of Transylvania by theHungariansis not known, the earliest Hungarian artifacts found in the region are dated to the first half of the tenth century.[36]In any case, after that time, the city became part of theKingdom of Hungary.KingStephen Imade the city the seat of thecastle countyof Kolozs, and King SaintLadislaus I of Hungaryfounded the abbey of Cluj-Mănăștur (Kolozsmonostor), destroyed during theTatarinvasions in 1241 and 1285.[19]As for the civilian colony, a castle and a village were built to the northwest of the ancient Napoca no later than the late 12th century.[19]This new village was settled by large groups ofTransylvanian Saxons,encouraged during the reign of Crown PrinceStephen,Duke of Transylvania.[18]The first reliable mention of the settlement dates from 1275, in a document of KingLadislaus IV of Hungary,when the village (Villa Kulusvar) was granted to the Bishop of Transylvania.[37]On 19 August 1316, during the rule of the new king,Charles I of Hungary,Cluj was granted the status of a city (Latin:civitas), as a reward for the Saxons' contribution to the defeat of the rebellious Transylvanianvoivode,Ladislaus Kán.[37]

The couple buried together and known as theLovers of Cluj-Napocaare believed to have lived between 1450 and 1550.[38][39]

Many craft guilds were established in the second half of the 13th century, and a patrician stratum based in commerce and craft production displaced the older landed elite in the town's leadership.[40]Through the privilege granted bySigismund of Luxembourgin 1405, the city opted out from the jurisdiction of voivodes, vice-voivodes and royal judges, and obtained the right to elect a twelve-member jury every year.[41]In 1488, KingMatthias Corvinus(born in Kolozsvár in 1443) ordered that the centumvirate—the city council, consisting of one hundred men—be half composed from thehomines bone conditiones(the wealthy people), with craftsmen supplying the other half; together they would elect the chief judge and the jury.[41]Meanwhile, an agreement was reached providing that half of the representatives on this city council were to be drawn from the Hungarian, half from the Saxon population, and that judicial offices were to be held on a rotating basis.[42]In 1541, Kolozsvár became part of the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (that transformed to Principality of Transylvania in 1570) after theOttoman Turksoccupied the central part of the Kingdom of Hungary; a period of economic and cultural prosperity followed.[42]AlthoughAlba Iulia(Gyulafehérvár) served as a political capital for the princes of Transylvania,Cluj(Kolozsvár) enjoyed the support of the princes to a greater extent, thus establishing connections with the most important centres of Eastern Europe at that time, along withKošice(Kassa),Kraków,Prague and Vienna.[41]

16th–18th centuries[edit]

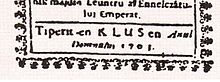

In terms of religion,Protestantideas first appeared in the middle of the 16th century. DuringGáspár Heltai's service as preacher,Lutheranismgrew in importance, as did the Swiss doctrine ofCalvinism.[43]By 1571, theTurda(Torda)Diethad adopted a more radical religion,Ferenc Dávid'sUnitarianism,characterised by the free interpretation of the Bible and denial of the dogma of theTrinity.[43]Stephen Báthoryfounded a CatholicJesuitacademy in the city in order to promote an anti-Reform movement; however, it did not have much success.[43]For a year, in 1600–1601, Cluj became part of thepersonal unionofMichael the Brave.[44][45]Under theTreaty of Carlowitzin 1699, it became part of theHabsburg monarchy.[46]

In the 17th century, Cluj suffered from great calamities, suffering from epidemics of theplagueand devastating fires.[43]The end of this century brought the end of Turkish sovereignty, but found the city bereft of much of its wealth, municipal freedom, cultural centrality, political significance and even population.[47]It gradually regained its important position within Transylvania as the headquarters of the Gubernium and the Diets between 1719 and 1732, and again from 1790 until therevolution of 1848,when the Gubernium moved to Nagyszeben (Hermannstadt), present-day Sibiu).[48]In 1791, a group ofRomanianintellectuals drew up a petition, known asSupplex Libellus Valachorum,which was sent to the Emperor in Vienna. The petition demanded the equality of the Romanian nation in Transylvania in respect to the other nations (Saxon, Szekler and Hungarian) governed by theUnio Trium Nationum,but it was rejected by the Diet of Cluj.[43]

19th century[edit]

Beginning in 1830, the city became the centre of the Hungarian national movement within the principality.[49]This erupted with theHungarian Revolution of 1848.The Austrian commanderKarl von Urbantook control of the city on 18 November 1848, following a battle.[50]At one point, the Austrians were gaining control of Transylvania as a whole, trapping the Hungarians between two flanks. But the Hungarian army, headed by thePolishgeneralJózef Bem,launched an offensive in Transylvania, recapturing Klausenburg by Christmas 1848.[51]

After the 1848 revolution, anabsolutistregime was established, followed by a liberal regime that came to power in 1860. In this latter period, the government granted equal rights to the ethnic Romanians, but only briefly. In 1865, the Diet in Cluj abolished the laws voted in Sibiu (Nagyszeben/Hermannstadt), and proclaimed the 1848 Law concerning the Union of Transylvania with Hungary.[49]A modern universitywas founded in 1872, with the intention of promoting the integration of Transylvania into Hungary.[52]Before 1918, the city's only Romanian-language schools were two church-run elementary schools, and the first printed Romanian periodical did not appear until 1903.[47]

After theAustro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867,Klausenburg and all of Transylvania were again integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary. During this time, Kolozsvár was among the largest and most important cities of the kingdom and was the seat ofKolozsCounty. Ethnic Romanians in Transylvania suffered oppression and persecution.[53]Their grievances found expression in theTransylvanian Memorandum,a petition sent in 1892 by the political leaders of Transylvania's Romanians to the Austro-HungarianEmperor-KingFranz Joseph.It asked for equal rights with the Hungarians and demanded an end to persecutions and attempts atMagyarisation.[53]The Emperor forwarded the memorandum to Budapest—the Hungarian capital. The authors, among themIoan Rațiuand Iuliu Coroianu, were arrested, tried and sentenced to prison for "high treason" in Kolozsvár/Cluj in May 1894.[54]During the trial, approximately 20,000 people who had come to Cluj demonstrated on the streets of the city in support of the defendants.[54]A year later, the King gave them pardon upon the advice of his Hungarian prime minister,Dezső Bánffy.[55]In 1897, the Hungarian government decided that only Hungarian place names should be used and prohibited the use of the German or Romanian versions of the city's name on official government documents.[56]

20th century[edit]

In the autumn of 1918, as World War I drew to a close, Cluj became a centre of revolutionary activity, headed byAmos Frâncu.On 28 October 1918, Frâncu made an appeal for the organisation of the "union of all Romanians".[57]Thirty-nine delegates were elected from Cluj to attend the proclamation of theunion of Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romaniain theGreat National AssemblyofAlba Iuliaon 1 December 1918;[57]the transfer of sovereignty was formalized by theTreaty of Trianonin June 1920.[58]Theinterwar yearssaw the new authorities embark on a "Romanianisation" campaign: aCapitoline Wolf statuedonated by Rome was set up in 1921; in 1932 a plaque written by historianNicolae Iorgawas placed onMatthias Corvinus's statue, emphasising his Romanian paternal ancestry; and construction of an imposingOrthodoxcathedral began, in a city where only about a tenth of the inhabitants belonged to the Orthodox state church.[59]This endeavour had only mixed results: by 1939, Hungarians still dominated local economic (and to a certain extent) cultural life: for instance, Cluj had five Hungarian daily newspapers and just one in Romanian.[59]

In 1940, Cluj, along with the rest ofNorthern Transylvania,became part ofMiklós Horthy's Hungary through theSecond Vienna Awardarbitrated byNazi GermanyandFascist Italy.[60][61][62]After the Germans occupied Hungary in March 1944 and installed a puppet government underDöme Sztójay,[63][64]they forced large-scaleantisemiticmeasures in the city. The headquarters of the localGestapowere located in the New York Hotel. That May, the authorities began the relocation of the Jews to theIris ghetto.[61]Liquidation of the 16,148 captured Jews occurred through six deportations toAuschwitzin May–June 1944.[61]Despite facing severe sanctions from the Hungarian administration, some Jews escaped across the border to Romania, with the assistance of intellectuals such asEmil Hațieganu,Raoul Șorban,Aurel Socol andDezső Miskolczy,as well as various peasants from Mănăștur.[61]

On 11 October 1944 the city was captured byRomanianandSoviettroops.[61][65]It was formally restored to theKingdom of Romaniaby theTreaty of Parisin 1947. On 24 January 6 March and 10 May 1946, the Romanian students, who had come back to Cluj after the restoration of northern Transylvania, rose against the claims of autonomy made by nostalgic Hungarians and the new way of life imposed by the Soviets, resulting in clashes and street fights.[66]

TheHungarian Revolution of 1956produced a powerful echo within the city; there was a real possibility that demonstrations by students sympathizing with their peers across the border could escalate into an uprising.[67][68]The protests provided the Romanian authorities with a pretext to speed up the process of "unification" of the local Babeș (Romanian) and Bolyai (Hungarian) universities,[69]allegedly contemplated before the 1956 events.[70][71]Hungarians remained the majority of the city's population until the 1960s. Then Romanians began to outnumber Hungarians,[72]due to the population increase as a result of the government's forced industrialisation of the city and new jobs.[73]During theCommunist period,the city recorded a high industrial development, as well as enforced construction expansion.[73]On 16 October 1974, when the city celebrated 1850 years since its first mention as Napoca, theCommunist governmentchanged the name of the city by adding "Napoca" to it.[27]

1989 revolution and after[edit]

During theRomanian Revolutionof 1989, Cluj-Napoca was one of the scenes of the rebellion: 26 were killed and approximately 170 injured.[74]After the end of totalitarian rule, the nationalist politicianGheorghe Funarbecame mayor and governed for the next 12 years. His tenure was marked by strong Romanian nationalism and acts ofethnicprovocation against the Hungarian-speaking minority. This deterred foreign investment;[11]however, inJune 2004,Gheorghe Funar was voted out of office, and the city entered a period of rapid economic growth.[11]From 2004 to 2009, the mayor wasEmil Boc,concurrently president of theDemocratic Liberal Party.He went on to be elected asprime minister,returning as mayor in 2012.[75][76]

Geography[edit]

Cluj-Napoca, located in the central part ofTransylvania,has a surface area of 179.5 square kilometres (69.3 sq mi). The city lies at the confluence of theApuseni Mountains,the Someș plateau and the Transylvanian plain.[77]It sprawls over the valleys ofSomeșul MicandNadăș,and, to some extent over the secondary valleys of the Popești, Chintău, Borhanci and Popii rivers.[78][79]The southern part of the city occupies the upper terrace of the northern slope ofFeleacHill, and is surrounded on three sides by hills or mountains with heights between 500 metres (1,600 ft) and 700 metres (2,300 ft).[79]The Someș plateau is situated to the east, while the northern part of town includesDealurile Clujului( "the Hills of Cluj" ), with the peaks, Lombului (684 m (2,244 ft)), Dealul Melcului (617 m (2,024 ft)), Techintău (633 m (2,077 ft)), Hoia (506 m (1,660 ft)) and Gârbău (570 m (1,870 ft)).[78]Other hills are located in the western districts, and the hills of Calvaria andCetățuia(Belvedere) are located near the centre of city.

Built on the banks of the river Someșul Mic, the city is also crossed over by brooks or streams such asPârâul Țiganilor,Pârâul Popești,Pârâul Nădășel,Pârâul Chintenilor,Pârâul Becaș,Pârâul Murătorii;Canalul Morilorruns through the centre of town.[78]

A wide variety of flora grow in theCluj-Napoca Botanical Garden;some animals have also found refuge there. The city has a number of other parks, of which the largest is theCentral Park.This park was founded during the 19th century and includes an artificial lake with an island, as well as the largest casino in the city,Chios.Other notable parks in the city are theIuliu HațieganuPark of theBabeș-Bolyai University,which features some sport facilities, theHașdeuPark, within the eponymous student housing district, the high-elevation Cetățuia, and the Opera Park, behind the building of theCluj-Napoca Romanian Opera.

Surroundings[edit]

The city is surrounded by forests and grasslands. Rare species of plants, such asVenus's slipperandiris,are found in the two botanical reservations of Cluj-Napoca,Fânațele ClujuluiandRezervația Valea Morii( "Mill Valley Reservation" ).[80]Animals such as boars, badgers, foxes, rabbits and squirrels live in nearby forest areas such as Făget and Hoia. The latter forest hosts the Romulus Vuia ethnographical park, with exhibits dating back to 1678.[81]Various people report alien encounters in theHoia-Baciu forest,large networks ofcatacombsthat connect the old churches of the city, or the presence of a monster in the nearby lake ofTarnița.[82][83]

A modern, 750-metre (820 yd)-longski resortsits on Feleac Hill, with an altitude difference of 98 metres (107 yd) between its highest and lowest points. This ski resort offers outdoor lighting,artificial snowand aski tow.[84]Băișoarawinter resortis located approximately 50 kilometres (31 mi) from the city of Cluj-Napoca, and includes two ski trails, for beginner and advanced skiers, respectively:Zidul MicandZidul Mare.[85]Two other summer resorts/spas are included in the metropolitan area, namelyCojocnaandSomeșeniBaths.[86]

There are a large number of castles in the countryside surroundings, constructed by wealthy medieval families living in the city. The most notable of them is theBonțida Bánffy Castle—once known as "theVersaillesof Transylvania "[87]—in the nearby village ofBonțida,32 kilometres (20 mi) from the city centre. In 1963, the castle was used as a set forLiviu Ciulei's filmForest of the Hanged,which won an award atCannes.[88]There are other castles located in the vicinity of the city; indeed, the castle at Bonțida is not even the only one constructed by the Bánffy family. The commune ofGilăufeatures the Wass-Bánffy Castle,[89]while another Bánffy Castle is located in theRăscruciarea.[90]In addition,Nicula Monastery,erected during the 18th century, is an important pilgrimage site in northern Transylvania. This monastery houses the renowned wonder-workingMadonnaof Nicula.[91][92]Theiconis said to have wept between 15 February and 12 March 1669.[93]During this time, nobles, officers, laity and clergy came to see it. At first they were sceptical, looking at it on both sides, but then humbly crossed themselves and returned home petrified by the wonder they had seen.[93]During the feast of theDormition of the Theotokos(commemorating the death of theVirgin Mary) on 15 August, more than 150,000 people from all over the country come to visit the monastery.[91]

Climate[edit]

Cluj-Napoca has awarm-summer humid continental climate(Köppen:Dfb). The climate is influenced by the city's proximity to theApuseni Mountains,as well as by urbanisation. Some West-Atlantic influences are present during winter and autumn. Winter temperatures are often below 0 °C (32 °F), even though they rarely drop below −10 °C (14 °F). On average, snow covers the ground for 65 days each winter.[94]In summer, the average temperature is approximately 20 °C (68 °F), despite the fact that temperatures sometimes reach 35 °C (95 °F) in mid-summer in the city centre. There are infrequent yet heavy and often violent storms in summer. During spring and autumn, temperatures vary between 0 °C (32 °F) to 22 °C (72 °F), with more frequent yet milder periods of rain.

The city has the best air quality in the European Union,[95]according to research published in 2014 by a French magazine and air-quality organization that studied the EU's hundred largest cities.[96]

| Climate data for Cluj-Napoca, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1901–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.1 (57.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.5 (90.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

38.0 (100.4) |

38.5 (101.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

32.6 (90.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.2 (22.6) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −34.2 (−29.6) |

−32.5 (−26.5) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

0.4 (32.7) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

−22.3 (−8.1) |

−27.9 (−18.2) |

−34.2 (−29.6) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 27.3 (1.07) |

24.8 (0.98) |

34.6 (1.36) |

51.0 (2.01) |

71.2 (2.80) |

91.0 (3.58) |

87.2 (3.43) |

64.7 (2.55) |

55.5 (2.19) |

45.3 (1.78) |

33.8 (1.33) |

34.0 (1.34) |

620.4 (24.43) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 6.0 (2.4) |

11.5 (4.5) |

5.8 (2.3) |

1.3 (0.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (0.2) |

2.6 (1.0) |

5.8 (2.3) |

33.5 (13.2) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.7 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 8.5 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 94.8 |

| Average snowy days | 13.6 | 10.3 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 11 | 46.7 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 87 | 82 | 74 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 76 | 76 | 78 | 81 | 86 | 88 | 79 |

| Averagedew point°C (°F) | −4.3 (24.3) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.0 (41.1) |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 70.2 | 100.9 | 159.2 | 188.7 | 230.1 | 253.1 | 265.7 | 260.7 | 190.2 | 153.5 | 89.4 | 54.6 | 2,016.3 |

| Mean dailydaylight hours | 9 | 10.3 | 11.9 | 13.6 | 15.1 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 14.2 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 12.2 |

| Averageultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1:NOAA(snow and Dew Point 1961–1990)[97][98]Romanian National Statistic Institute,[99] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2:Deutscher Wetterdienst(humidity, 1973–1993),[100]Weather Atlas (Daylight-UV),[101]Meteomanz (snow days 2000-2023, extremes since 2021)[102] | |||||||||||||

Law and government[edit]

Administration[edit]

The city government is headed by amayor.[103]Since 2012, the office is held byEmil Boc,who was returned at that year'slocal electionfor a third term, having resigned in 2008 to becomePrime Minister.[76]Decisions are approved and discussed by the local government (consiliu local) made up of 27 elected councillors.[103]The city is divided into 15 districts (cartiere) laid out radially. City hall intends to develop local administrative branches for most of the districts.

| Party | Seats | Current Local Council[104] | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Liberal Party(PNL) | 16 | |||||||||||||||||

| Save Romania Union(USR) | 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Democratic Alliance of Hungarians(UDMR/RMDSZ) | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Social Democratic Party(PSD) | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

Because of the last years' massive urban development, in 2005 some areas of Cluj were named as districts (Sopor, Borhanci, Becaș, Făget, Zorilor South), but most of them are still construction sites.[105]Beside these, there are some other building areas likeTineretului,LombuluiorOser,which are likely to become districts in the following years.[106]

Additionally, as Cluj-Napoca is the capital ofCluj County,the city hosts the palace of the prefecture, the headquarters of thecounty council(consiliu județean) and theprefect,who is appointed by Romania's central government.[103]The prefect is not allowed to be a member of a political party, and his role is to represent the national government at the local level, acting as a liaison and facilitating the implementation of National Development Plans and governing programmes at the local level.[103]Like all other local councils in Romania, the Cluj-Napoca local council, the county council and the city's mayor are elected every four years by the population.[103]

Cluj-Napoca is also the capital of the historical region ofTransylvania,a status that resonates to this day. Currently, the city is the largest in theNord-Vest development region,which is equivalent toNUTS-IIregions in theEuropean Unionand is used by the European Union and the Romanian Government for statistical analysis and regional development. The Nord-Vest development region is not, however, an administrative entity.[103]TheCluj-Napoca metropolitan areabecame operational in December 2008,[8]and comprises a population of 411,379.[4][7]Besides Cluj-Napoca, it includes seventeencommunes:Aiton,Apahida,Baciu,Bonțida,Borșa,Căianu,Chinteni,Ciurila,Cojocna,Feleacu,Florești,Gârbău,Gilău,Jucu,Petreștii de Jos,TureniandVultureni.

The executive presidium of theDemocratic Union of Hungarians in Romania(UDMR) and all its departments are headquartered in Cluj,[107][108]as are local and regional organisations of most Romanian political parties. In order to counterbalance the political influence of Transylvania's Hungarian minority, nationalist Romanians in Transylvania founded theParty of Romanian National Unity(PUNR) at the beginnings of the 1990s; the party was present in the Romanian Parliament during the 1992–1996 legislature.[109]The party eventually moved its main offices to Bucharest and fell into decline as its leadership joined the ideologically similarPRM.[109]In 2008, theInstitute for Research on National Minorities,subordinated to theRomanian Government,opened its official headquarters in Cluj-Napoca.[110]

Eleven hospitals function in the city, nine of which are run by the county and two (for oncology and cardiology) by thehealth ministry.Additionally, there are well over a hundred private medical cabinets and dentists' offices each.[79]In 2022, work began on an emergency hospital for the entireNorth-West region;the cost is estimated at over 500 million euros.[111][112][113]

Justice system[edit]

Cluj-Napoca has a complex judicial organisation, as a consequence of its status ofcountycapital. The Cluj-Napoca Court of Justice is the local judicial institution and is under the purview of the Cluj County Tribunal, which also exerts its jurisdiction over the courts ofDej,Gherla,Turda,andHuedin.[114]Appeals from these tribunals' verdicts, and more serious cases, are directed to the Cluj Court of Appeals. The city also hosts the county's commercial and military tribunals.[114]

Cluj-Napoca has its own municipal police force,Poliția Municipiului Cluj-Napoca,which is responsible for policing of crime within the whole city, and operates a number of special divisions. The Cluj-Napoca Police are headquartered on Decebal Street in the city centre (with a number of precincts throughout the city) and it is subordinated to theCounty's Police Inspectorateon Traian Street.[115]City Hall has its own community police force,Poliția Primăriei,dealing with local community issues. Cluj-Napoca also houses theCounty's Gendarmerie Inspectorate.

Crime[edit]

Cluj-Napoca and the surrounding area (Cluj County) had a rate of 268 criminal convictions per 100,000 inhabitants during 2006, just above the national average.[116]After therevolution in 1989,the criminal conviction rate in the county entered a phase of sustained growth, reaching a historic high of 429 in 1998, when it began to fall.[116]Although the overall crime rate is reassuringly low, petty crime can be an irritant for foreigners, as in other large cities of Romania.[117]During the 1990s, two large financial institutions, Banca Dacia Felix andCaritas,went bankrupt due to large-scale fraud and embezzlement.[118][119]

Also notorious was the case of serial killerRomulus Vereș,"the man with the hammer"; during the 1970s, he was charged with five murders and severalattempted murders,but never imprisoned ongrounds of insanity:he hadschizophrenia,blaming theDevilfor his actions. Instead, he was institutionalised in the Ștei psychiatric facility in 1976, following a three-yearforensicinvestigation during which four thousand people were questioned.Urban mythsbrought the number of victims up to two hundred women, though the actual number was much smaller. This confusion is probably explained by the lack of attention this case received, despite its magnitude, in the Communist press of the time.[120]

A 2006 poll shows a high degree of satisfaction with the work of the local police department. More than half the people surveyed during a 2005–2006 poll declared themselves satisfied (62.3%) or very satisfied (3.3%) with the activity of the county police department.[121]The study found the highest satisfaction with car traffic supervision, the presence of officers in the street, and road education; on the negative side, corruption and public transport safety remain concerns.

Efforts made by local authorities in the Cluj-Napoca district at the end of the 1990s to reform the protection ofchildren's rightsand assistance forstreet childrenproved insufficient due to lack of funding, incoherent policies and the absence of any real collaboration between the actors involved (Child Rights Protection Directorate, Social Assistance Service within the District Directorate for Labour and Social Protection, Minors Receiving Centre, Guardian Authority within the City Hall, Police). There are numerous street children, whose poverty and lack of documented identity brings them into constant conflict with local law enforcement.[122]

Following cooperation between the local governmental council and thePrison FellowshipRomania Foundation,homelesspeople, street children andbeggarsare taken, identified and accommodated within the Christian Centers for Street Children and Homeless People, respectively, and the Ruhama centre.[123]The latter features a marshaling center for beggars and street children, as well as aflophouse.[124]As a consequence, the fluctuating movement of children, beggars and homeless people in and out of the centre has been considerably reduced, with most of the initial beneficiaries successfully integrated into the programme rather than returning to the streets.[122]

From 2000 onwards, Cluj-Napoca has seen an increase in illegalroad races,which occur mainly at night on the city's outskirts or on industrial sites and occasionally produce victims. There have been attempts to organize legal races as a solution to this problem.[125]

Demographics[edit]

| Historical population of Cluj-Napoca | |||||||||||||

| Year | Population | %± | Romanians | Hungarians | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1453 est. | 6,000[126] | — | — | — | |||||||||

| 1703 | 7,500[127] | 25% | — | — | |||||||||

| 1714 | 5,000[128] | −33.3% | — | — | |||||||||

| 1770 | 10,500[129] | 110% | — | — | |||||||||

| 1785 | 9,703[127][130] | −7.6% | — | — | |||||||||

| 1787 | 10,476[127][130] | 7.9% | — | — | |||||||||

| 1835 | 14,000[127][131] | 33.6% | — | — | |||||||||

| 1850 | 19,612 | 40% | 21.0% | 62.8% | |||||||||

| 1880 | 32,831 | 67.4% | 17.1% | 72.1% | |||||||||

| 1890 | 37,184 | 13.2% | 15.2% | 79.1% | |||||||||

| 1900 | 50,908 | 36.9% | 14.1% | 81.1% | |||||||||

| 1910 census[b] | 62,733 | 23.2% | 14.2% | 81.6% | |||||||||

| 1920 | 85,509 | 36.3% | 34.7% | 49.3% | |||||||||

| 1930 census | 100,844[132] | 17.9% | 34.6% | 47.3% | |||||||||

| 1941[c][d] | 114,984 | 14% | 9.8% | 85.7% | |||||||||

| 1948 census | 117,915 | 2.5% | 40% | 57% | |||||||||

| 1956 census[e] | 154,723 | 31.2% | 47.8% | 47.9% | |||||||||

| 1966 census | 185,663 | 20% | 56.5% | 41.4% | |||||||||

| 1977 census | 262,858 | 41.5% | 65.8% | 32.8% | |||||||||

| 1992 census | 328,602 | 25% | 76.6% | 22.7% | |||||||||

| 2002 census | 317,953[133] | −3.2% | 79.4% | 19.0% | |||||||||

| 2011 census[f] | 324,576[134][4][135] | 2.1% | 81.5% | 16.4% | |||||||||

| 2021 census | 286,598[136] | −11.7% | 84.6% | 13.9% | |||||||||

|

Source (if not otherwise specified): | |||||||||||||

The city's population, at the2021 census,was 286,598 inhabitants,[5]marking a decrease from the figure recorded at the 2011 census (324,576 inhabitants). The population of theCluj-Napoca metropolitan areawas estimated at 411,379 (2011).[4][6]As defined byEurostat,the Cluj-Napocafunctional urban areahas a population of 379,733 residents (as of 2015[update]).[137]Finally, the population of the peri-urban area numbers over 420,000 residents.[4][7]The newmetropolitan government of Cluj-Napocabecame operational in December 2008.[8]According to the 2007 data provided by the County Population Register Service, the total population of the city is as high as 392,276 people.[9]The variation between this number and the census data is partially explained by the real growth of the population residing in Cluj-Napoca, as well as by different counting methods: "In reality, more people live in Cluj than those who are officially registered", Traian Rotariu, director of the Center for Population Studies, toldFoaia Transilvană.[9]Moreover, this number does not include the floating population—an average of over 20 thousand people each year during 2004–2007, according to the same source.[9]

Ethnic composition of Cluj-Napoca (2021)

Religious composition of Cluj-Napoca (2021)

In the modern era, Cluj's population experienced two phases of rapid growth, the first in the late 19th century, when the city grew in importance and size, and the second during theCommunist period,when a massive urbanisation campaign was launched and many peoplemigrated from rural areasand from beyond the Carpathians to the county's capital.[138]About two-thirds of the population growth during this era was based onnet migrationinflows; after 1966, the date of Ceaușescu's ban on abortion and contraception,natural increasewas also significant, being responsible for the remaining third.[73]

From theMiddle Agesonwards, the city of Cluj has been a multicultural city with a diverse cultural and religious life. In 1930, the city was 26.7% Reformed, 22.6% Greek Catholic, 20.1% Roman Catholic, 13.4% Jewish, 11.8% Orthodox, 2.4% Lutheran and 2.1% Unitarian.[139]Contributing factors for demographic shifts were the extermination[140]and emigration[141]of the city's Jews, the outlawing of the Greek-Catholic Church (1948–89)[142]and the gradual decline in the Hungarian population.

On a more historical note, the Jewish community has figured centrally in the history of Transylvania, and in that of the wider region.[143]They were a substantial and increasingly vibrant presence in Cluj in the modern era, contributing significantly to the town's economic dynamism and cultural flourishing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[143]Although the community comprised a significant share of the town's population during the interwar era—between 13 and 15 percent[144]—this figure plummeted as a consequence of theHolocaustand emigration; by the 1990s only a few hundred Jews remained in Cluj-Napoca.[143]

In the 14th century, most of the town's inhabitants and the local elite wereSaxons,[42]largely descended from settlers brought in by theKings of Hungaryin the twelfth and thirteenth centuries[145]to develop and defend the southern borders of the province.[145]By the middle of the next century roughly half the population had Hungarian names. In Transylvania as a whole, the Reformation sharpened ethnic divisions: Saxons became Lutheran while Hungarians either remained Catholic or became Calvinist or Unitarian. In Kolozsvár, however, the religious lines were blurred. Isolated both geographically from the main areas of German settlement in southern Transylvania[143]and institutionally because of their distinctive religious trajectory, many Saxons eventually assimilated to the Hungarian majority over several generations. New settlers to the town largely spoke Hungarian, a language that many Saxons gradually adopted.[42](In the seventeenth century, out of more than thirty royal free towns, only seven had a Hungarian majority, with Kolozsvár/Klausenburg being one of them;[146]the rest were largely German-dominated.[146]) In this manner Kolozsvár became largely Hungarian speaking and would remain so through the mid-20th century, though 4.8% of its residents identified as German as late as 1880.[147]

TheRomaform a sizable minority in contemporary Romania, and a small but visible presence in Cluj-Napoca: self-identifying Roma in the city comprise only 1 percent of the population; yet they are a familiar presence in and around the central market, selling flowers, used clothes, and tinware.[143]They are an important object of public discourse and media representation at the national level; however, Cluj-Napoca, with its small Roma population, has not been a major focus of Roma ethno-political activity.[143]

Hungarian community[edit]

Almost 50,000Hungarianslive in Cluj-Napoca. The city is home to the second-largest urban Hungarian community in Romania, afterTârgu Mureș,[135]with an active cultural and academic life: the city features aHungarian state theatreandopera,as well as Hungarian research institutions, such asErdélyi Múzeumi Egyesület(EME),Erdélyi Magyar Műszaki Tudományos TársaságandBolyai Társaság.[148]With respect to religious affairs, the city houses central offices for theReformedDiocese of Transylvania, theUnitarianDiocese and an Evangelical Lutheran Church Diocese (all of which train their clergy at theProtestant Theological Institute of Cluj). Several newspapers and magazines are published in theHungarian language,yet the community also receives public and private television and radio broadcasts (seeCulture and media). As of 2007[update],7,000 students attended courses in the 55 Hungarian-language specialisations at theBabeș-Bolyai University.[149]Gheorghe Funar,mayor of Cluj-Napoca from 1992 to 2004, was notorious for acts of ethnic provocation, bedecking the city's streets in the colours of the Romanian flag and arranging pickets outside the city's Hungarian consulate; however, tensions have subsided since.[11]Since 2010, theHungarian Cultural Days of Clujfestival takes place each summer.[150]

Economy[edit]

Cluj-Napoca is an important economic centre in Romania. Local brands that have become well known at a national, and to some extent even international level, include:Banca Transilvania,[151]Terapia Ranbaxy,[152]Farmec,[153]Jolidon,[154]andUrsusbreweries.[155]

The American online magazineInformationWeekreports that much of the software/ITactivity in Romania is taking place in Cluj-Napoca, which is quickly becoming Romania'stechnopolis.[156]Nokiainvested 200 million euros in a mobile telephone factory near Cluj-Napoca;[157]this began production in February 2008 and closed in December 2011.[158]It also opened a research centre in the city[159]that was shut down in April 2011.[160]The former Nokia factory was purchased by Italian appliance manufacturerDe'Longhi.[161]The city houses regional or national headquarters ofMOL,[162]Aegon,[163]Emerson,[164]De'Longhi,[165]Bechtel,[166]FrieslandCampina,[167]Office Depot,Genpact[168]andNew Yorker.[169]Boschhas also built a factory near Cluj-Napoca, in the same industrial park as De'Longhi.[170]

Cluj-Napoca is also an important regional commercial centre, with many streetmallsandhypermarkets.Eroilor Avenueand Napoca and Memorandumului streets are the most expensive venues, with a yearly rent price of 720 euro/m2,[171]butRegele Ferdinandand 21 Decembrie 1989 avenues also feature high rental costs. There are two large malls:VIVO!(including aCarrefourhypermarket) andIulius Mall(including anAuchanhypermarket). Other large stores include branches of various international hypermarket chains, likeCora,Metro,Selgrosand do-it-yourself stores such asBaumaxandPraktiker.

Among the retailers found in the city's shopping centers are H&M, Zara, Guess, Camaïeu, Bigotti, Orsay, Jolidon, Kenvelo, Triumph, Tommy Hilfiger, Sephora, Yves Rocher, Swarovski, Ecco, Bata, Adidas, Converse, and Nike.[172]

In 2021, the city's general budget was 2.117 billionlei,the equivalent of over 433 millionEuros.[173]This marks a 114% increase over the 2008 level of 990 million lei[174]or 266 millionEuros.

Tourism[edit]

In 2007, the hotel industry in the county of Cluj offered total accommodations of 6,472 beds, of which 3,677 were in hotels, 1,294 in guesthouses and the rest in chalets, campgrounds, or hostels.[175]A total of 700,000 visitors, 140,000 of whom were foreigners, stayed overnight.[175]However, a considerable share of visits is made by those who visit Cluj-Napoca for a single day, and their exact number is not known. The largest numbers of foreign visitors come from Hungary, Italy, Germany, the United States, France, and Austria.[175]Moreover, the city's 140 or so travel agencies help organise domestic and foreign trips; car rentals are also available.[176]

Arts and culture[edit]

Cluj-Napoca has a diverse and growing cultural scene, with cultural life exhibited in a number of fields, including thevisual arts,performing artsandnightlife.The city's cultural scene spans its history, dating back to Roman times: the city started to be built in that period, which has left its mark on the urban layout (centered on today's Piața Muzeului) as well as surviving ruins. However, the medieval town saw a shift in its centre towards new civil and religious structures, notablySt. Michael's Church.[177] During the 16th century the city became the chief cultural and religious centre of Transylvania;[178]in the 1820s and the first half of the 1830s, Kolozsvár was the most important centre for Hungarian theatre and opera,[179]while at the beginning of the 20th century, still a Hungarian city, it became the chief alternative to the cinematography of Budapest.[180]After its incorporation into theKingdom of Romaniaat the end of World War I, the renamed Cluj saw a resurgence of its Romanian culture, most conspicuous in the completion of the monumental Orthodox cathedral in 1933 across from the (newly nationalised)Romanian National Theatre.[181]This marked an unambiguously "Romanian" centre, a few blocks to the east of the old Hungarian centre;[181]however, the Romanian-ness of the town—like the Romanian hold on Transylvania—was by no means securely established even by the end of the interwar period.[181]The late 1960s brought a revival of nationalist discourse, concomitant with the urbanisation and industrialisation of the city that gradually advanced theRomanianisationof the city.[182]Nowadays, the city is home to people of different cultures, with corresponding cultural institutions such as the Hungarian State Theatre, as well as theBritish Counciland various other centres for the promotion of foreign cultures. These institutions hold eclectic manifestations in honour of their cultures, includingBessarabian,[183]Hungarian,[184]Tunisian,[185]and Japanese.[186]Nevertheless, contemporary cultural manifestations cross ethnic boundaries, being aimed at students, cinephiles, and arts and science lovers, among others.

Landmarks[edit]

Cluj-Napoca has a number of landmark buildings and monuments. One of those is theSaint Michael's ChurchinUniriiSquare,built at the end of the 14th century in theGothic styleof that period. It was only in the 19th century that theNeo-Gothictower of the church was erected; it remains the tallest church tower in Romania to this day.[187]

In front of the church is theequestrian statue of Matthias Corvinus,erected in honour of the locally bornKing of Hungary.TheOrthodox Church'sequivalent to St. Michael's Church is theOrthodox CathedralonAvram IancuSquare,built in theinterwarera. TheRomanian Greek-Catholic Churchalso has a cathedral in Cluj-Napoca,Transfiguration Cathedral.[citation needed]

Another landmark of Cluj-Napoca is thePalace of Justice,built between 1898 and 1902, and designed by architect Gyula Wagner in aneclecticstyle.[188]This building is part of an ensemble erected in Avram Iancu Square that also includes the National Theatre, the Palace ofCăile Ferate Române,the Palace of the Prefecture, the Palace of Finance and the Palace of the Orthodox Metropolis. An important eclectic ensemble isIuliu Maniu Street,featuring symmetrical buildings on either side, after the urbanistic trend ofGeorges-Eugène Haussmann.[189]A highlight of the city is thebotanical garden,situated in the vicinity of the centre. Beside this garden, Cluj-Napoca is also home to some large parks, the most notable being theCentral Parkwith the Chios Casino and a large statuary ensemble. Many of the city's notable figures are buried in Hajongard Cemetery, which covers 14 hectares (35 acres).[citation needed]

As an important cultural centre, Cluj-Napoca has many theatres and museums. The latter include theNational Museum of Transylvanian History,theEthnographic Museum,theCluj-Napoca Art Museum,the Pharmacy Museum, the Water Museum and the museums ofBabeș-Bolyai University—the University Museum, the Museum of Mineralogy, the Museum of Paleontology and Stratigraphy, the Museum of Speleology, the Botanical Museum and the Zoological Museum.

Visual arts[edit]

In terms ofvisual arts,the city contains a number of galleries featuring both classical and contemporary Romanian art, as well as selected international works.

TheNational Museum of Artis located in the former palace of the count György Bánffy, the most representative secular construction built in theBaroquestyle inTransylvania.[190][191][192]The museum features extensive collections of Romanian art, including works of artists likeNicolae Grigorescu,Ștefan LuchianandDimitrie Paciurea,as well as some works of foreign artists likeKároly Lotz,Luca Giordano,Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin,Herri met de BlesandClaude Michel,[193]and was nominated to be European Museum of the Year in 1996.[194]

The most notable of the city's other galleries is theGallery of the Union of Plastic Artists.Situated in the city centre, this gallery presents collections drawn from the contemporary arts scene. The Gallery of Folk Art includes traditional Romanian interior decoration artworks.

Historically, the city was one of the most important cultural and artistic centres in 16th-century Transylvania. The Renaissance workshop, formed in 1530 and strongly supported by the Transylvanian princes, served local and wider requirements: from the middle of the century onwards, when theOttomanshadconqueredcentral Hungary, it extended its activity throughout the new principality. Its style, the "Flower Renaissance", used a variety of plant ornament enriched with coats of arms, figures and inscriptions. It continued to be of great importance into the 18th century, and traces of it are still apparent in 20th-century vernacular art; Klausenburg was central to the long, anachronistic survival of the style, particularly among Hungarians.[195]

Performing arts[edit]

The city has a number of renowned facilities and institutions involvingperforming arts.The most prominent is theNeo-baroquetheatre at theAvram Iancu Square.[196]Built at the beginning of the 20th century by theViennesecompanyHelmer and Fellner,this structure is inscribed inUNESCO's list of specially protected monuments.[197]Since 1919, shortly after the union of Transylvania with Romania, the building has hosted theLucian Blaga National Theatreand theRomanian National Opera.The Transylvania Philharmonic, founded in 1955, gives classical music concerts.[198]The multiculturalism in the city is once again attested by theHungarian Theatre and Opera,home for four professional groups of performers. There is also a number of smaller independent theatres, including the Puck Theatre, where puppet shows are performed.

Music and nightlife[edit]

Cluj-Napoca is the residence of some well-known Romanian musicians. Examples of homegrown bands include the Romanian alternative rock bandKumm,the rock bandCompact,[199]therhythm and bluesbandNightlosers,[200]thealternativebandLuna Amară,[201]Grimus—the winners of the 2007 National Finals ofGlobal Battle of the Bands,[202]the modern pop bandSistem—which finished third in theEurovision Song Contest 2005,[203]as well as a large assortment of electronic music producers, notably Horace Dan D.[204]The Cheeky Girlsalso grew up in the city, where they studied at the High School of Choreography and Dramatic Art.[205]While manydiscosplay commercialhouse music,the city has an increasingminimal technoscene, and, to an extentjazz/bluesandheavy metal/punk.The city's nightlife, particularly itsclubscene, grew significantly in the 1990s, and continues to increase. Most entertainment venues are dispersed throughout the city centre, spreading from the oldest one of all,Diesel Club,[206]onUnirii Square.The list of large and fancy clubs continues withObsession The ClubandMidi,the latter being a venue for the new minimal techno music genre. These three clubs are classified as the top three clubs in the Transylvania-Banat region in a chart published by the national dailyRomânia Liberă.[206]The Unirii area also features theFashion Bar,with an exclusive terrace sponsored byFashion TV.Some other clubs in the centre are Aftereight, Avenue, Bamboo, Decadence, Kharma and Molotov Pub. Numerous restaurants, pizzerias and coffee shops provide regional as well as international cuisine; many of these offer cultural activities like music and fashion shows or art exhibitions.[176]

The city also includesStrada Piezișă(slanted street), a central nightlife strip located in the Hașdeu student area, where a large number of bars and terraces are situated. Cluj-Napoca is not limited to these international music genres, as there are also a number ofdiscoswhere local "Lăutari"playmanele,a Turkish-influenced type of music.

Traditional culture[edit]

In spite of the influences of modern culture, traditional Romanian culture continues to influence various domains of art.

Cluj-Napoca hosts anethnographicmuseum, the Ethnographic Museum of Transylvania, which features a large indoor collection of traditional cultural objects, as well as an open-air park, the oldest of this kind in Romania, dating back to 1929.[207][208]

TheNational Museum of Transylvanian Historyis another important museum in Cluj-Napoca, containing a collection of artefacts detailing Romanian history and culture from prehistoric times, theDacianera, medieval times and the modern era.[209]Moreover, the city also preserves a Historic Collection of the Pharmacy, in the building of its first pharmacy (16th century), theHintz House.[209]

Cultural events and festivals[edit]

Cluj-Napoca hosts a number of cultural festivals of various types. These occur throughout the year, though are more frequent in the summer months. "Sărbătoarea Muzicii" (Fête de la Musique) is a music festival taking place yearly on 21 June in a number of Romanian cities, Cluj-Napoca included, organised under the aegis of the French Cultural Centre.[210]Additionally, Splaiul Independenței, on the banks of Someșul Mic, hosts a number of beer festivals throughout the summer, among them the "Septemberfest",modelled after the GermanOktoberfest.[211]In 2015, the city will be theEuropean Youth Capital,an event with a budget of 5.7 million euros that is projected to boost tourism by about a fifth.[212]

The city has seen a number of important music events, including theMTV RomâniaMusic Award ceremony which was held at theSala Sporturilor Horia Demianin 2006 with theSugababes,PachangaandUniting Nationsas special international guests.[213]In 2007,Beyoncéalso performed in Cluj-Napoca, at theIon Moina Stadium.[214]In 2010,Iron Maidenincluded the city in theirFinal Frontier World Tour.[215]TheCluj Arenawas inaugurated in 2011 with concerts byScorpionsandSmokie,the main event drawing over 40,000 people;[216]other events followed, for instanceRoxettein 2012[217]andDeep Purplein 2013.[218]Smaller events occur regularly at thePolyvalent Hall,the Opera and the Students' House of Culture. Moreover, the local clubs regularly organise events featuring international artists, usually foreign disc jockeys, likeAndré Tanneberger,Sasha,Timo Maas,Tania Vulcano,Satoshi Tomiie,Yves Larock,Dave Seaman,Plump DJs,Stephane KorAndy Fletcher.

TheTransilvania International Film Festival(TIFF), held in the city since 2001 and organised by the Association for the Promotion of the Romanian Film, is the first Romanian film festival for international features.[219]The festival jury awards the Transilvania Trophy for the best film in competition, as well as prizes for best director, best performance and best photography. With the support ofHome Box Office,TIFF also organises a national script contest.Comedy Cluj,which debuted in 2009, is the newest annual film festival organised in Cluj-Napoca.[220]

Toamna Muzicală Clujeană,Romania's most important classical music event after theGeorge Enescu Festival,has taken place annually since 1965, and is run by theTransylvania State Philharmonic Orchestra.[221]A Mozart Festival has taken place annually since 1991.[222]Another annual event, taking place at the Romanian National Opera, is the Opera Ball, established in 1992.[223]Additionally, in 2012, a Festival of National Operas was introduced, which aside from the hometown troupe, also features opera companies fromBucharest,IașiandTimișoara.[224]The Interferences International Theatre Festival, started in 2007, takes place at the Hungarian Theatre.[225]

Also held in the city is Delahoya, Romania's oldestelectronic musicfestival, established in 1997.[226]Electric Castle Festival,which takes place atBánffy Castlein nearbyBonțida,had an audience of over 30,000 people for its first edition in 2013 and was nominated byEuropean Festivals Awardsfor the Best New Festival and Best Medium Size Festival awards.[227]By 2016, over 120,000 were in attendance.[228]Untold Festival,which began in 2015, is Romania's largest music festival. Held mainly in theCluj Arena,and also at thePolyvalent Hall,it drew over 300,000 in its second edition.[229][230]

Architecture[edit]

Cluj-Napoca's salient architecture is primarilyRenaissance,BaroqueandGothic.The modern era has also produced a remarkable set of buildings from themid-century style.The mostly utilitarian Communist-era architecture is also present, although only to a certain extent, as Cluj-Napoca never faced a largesystematisationprogramme. Of late, the city has seen significant growth in contemporary structures such as skyscrapers and office buildings, mainly constructed after 2000.[231]

Historical architecture[edit]

The nucleus of the old city, an important cultural and commercial centre, used to be a military camp, attested in documents with the name "castrum Clus".

The oldest residence in Cluj-Napoca is theMatthias Corvinus House,originally a Gothic structure that bears TransylvanianRenaissancecharacteristics due to a later renovation.[232]Such changes feature on other Hungarian townspeople's residences, built from the mid-15th century mostly of stone and wood with a cellar, ground floor and upper storey, in the Late Gothic and Renaissance styles; although the late medieval houses have often been considerably altered, the street façades of the old town are mostly preserved.[195]St. Michael's Church,the oldest and most representative Gothic-style building in the country, dates back to the 14th century. The oldest of its sections is the altar, dedicated in 1390, while the newest part is the clock tower, which was built inGothic Revivalstyle (1860).[187]

As Renaissance styles survived late in the city, the appearance of Baroque art was also delayed, but from the mid-18th century Klausenburg was once again at the centre of the development and spread of art in Transylvania, as it had been two centuries earlier. The first enthusiasts for Baroque were the Catholic Church and the landed aristocracy. Artists came initially from south Germany and Austria, but by the end of the century most of the work was by local craftsmen. The earliest signs of the new style appear in the furnishings of St. Michael's church: the altarpieces and pulpit, which date to the 1740s, are carved, painted and richly decorated with figures. An altarpiece depicting theAdoration of the Magi(1748–50) is the work ofFranz Anton Maulbertsch.Theearliest two-towered Baroque churchwas built by the Jesuits from 1718 to 1724 on the pattern ofKošiceand was later handed over to the Piarists. During the century more simply designed Baroque churches were built for the mendicant orders, Lutherans, Unitarians and the Orthodox Church. The noble families built houses and even palaces in the old town.[195]The BaroqueBánffy Palace(1774–1785), constructed around a rectangular yard, is the masterpiece of Eberhardt Blaumann. Its peculiarity lies in the appearance of the principal façade.[231]

BothAvram IancuandUnrii Squaresfeature ensembles ofeclecticandbaroque–rococoarchitecture, including thePalace of Justice,[188]theTheatre,[196]theIuliu Maniu symmetrical street,[189]and the New York Palace, among others.[233]In the 19th century many houses were built in the Neo-classical, Romantic and Eclectic styles. Also dating to that period are thetwo-towered Neo-classical Calvinist church(1829–50), its new college building of 1801, and the City Hall (1843–46) in the marketplace, byAntal Kagerbauer.[195]

The banks of the Someșul Mic also feature a wide variety of such old buildings. The end of the 19th century brought a building ensemble that fastens the corners of the oldest bridge over the river, at the north end of theRegele Ferdinand Avenue.The Berde, Babos, Elian, Urania, andSzékipalaces consist of a mixture of Baroque, Renaissance and Gothic styles, following theArt Nouveau/Secession and Revival specifics.[234]

In the 2000s, the old city centre underwent extensive restoration works, meant to convert much of it into a pedestrian area, includingBulevardul Eroilor,Unirii Squareand other smaller streets.[235]In some residential areas of the city, particularly the high-income southern areas, likeAndrei MureșanuorStrada Republicii,there are manyturn-of-the-centuryvillas.

Modern and Communist architecture[edit]

Part of Cluj-Napoca's architecture is made up of buildings constructed during theCommunist era,when historical architecture was replaced with "more efficient" high-density apartment blocks. Nicolae Ceaușescu's project ofsystematisationdid not really affect the heart of the city, instead reaching the marginal, shoddily built districts surrounding it.[231]

Still, the centre hosts some examples of modern architecture dating back to the Communist era. The Hungarian Theatre building was erected at the beginning of the 20th century, but underwent an avant-garde renovation in 1961, when it acquired amodernist style of architecture.[236]Another example of modernist architectural art isPalatul Telefoanelor,situated in the vicinity ofMihai ViteazulSquare, an area that also features a complex of large apartment buildings.

Some outer districts, especiallyMănăștur,and to a certain extentGheorgheniandGrigorescu,consist mainly of such large apartment ensembles.[231]

Contemporary architecture[edit]

Since 1989, modern skyscrapers and glass-fronted buildings have altered the skyline of Cluj-Napoca. Buildings from this time are mostly made out of glass and steel, and are usually high-rise. Examples include shopping malls (particularly theIulius Mall), office buildings and bank headquarters. Of this last, regional headquarters of theBanca Română pentru Dezvoltareis the tallest office building in Cluj-Napoca, with 50 metres (160 ft).[237]Its twelve storeys were completed in 1997 after 4 years of work and house offices for the bank and for divisions of several other companies, including insurance and oil companies.

Anotherarchitecturallyinteresting building is the so-called "Clădirea biscuite" (the biscuit building). This building was supposed to house the local headquarters of the Banca Agricolă (Agricultural Bank), but entered in the custody of the city due to the failure of that bank in the 1990s and its subsequent purchase by theRaiffeisen Bank,to be eventually converted in an office building.[238]

The headquarters ofBanca Transilvania,at the intersection ofRegele Ferdinand Avenueand Barițiu Street, is also a large contemporary building and was originally constructed to host the regional offices ofRomtelecom,the public phone company, but was later sold to the bank.[239]

Cluj-Napoca is undergoing a period of architectural revitalisation that is set to bring the manner of expansion to the vertical. Afinancial centre,containing a tower of 15 storeys, is slated for completion in 2010 on Ploiești Street.[240]Two 35-storeytwin towersare projected to be constructed in the Sigma area in Zorilor,[241][242]while theFloreștiarea will host a complex of three towers with 32 levels each.[243]As of February 2020, the aforementioned projects were never completed or were postponed indefinitely.

Transport[edit]

Cluj-Napoca has a complex system of regional transportation, providing road, air and rail connections to major cities in Romania and Europe. It also features a public transportation system consisting of bus, trolleybus and tram lines.

Road[edit]

Cluj-Napoca is an important node in theEuropean road network,being on three different European routes (E60,E81andE576). At anational level,Cluj-Napoca is located on three different main national roads:DN1,DN1C and DN1F. TheRomanian Motorway A3,also known asTransylvania Motorway(Autostrada Transilvania), currently under construction, will link the city withBucharestand Romania's western border.[244]The 2B section betweenCâmpia Turziiand Cluj Vest (Gilău) opened in late 2010.[245][246]The Cluj-Napoca Coach Station (Autogara) is used by several private transport companies to providecoachconnections from Cluj-Napoca to a large number of locations from all over the country.

The number of automobiles licensed in Cluj-Napoca is estimated at 175,000.[247]As of 2007[update],Cluj Countyranks sixth nationwide according to the cars sold during that year, with 12,679 units, corresponding to a four percent share. One tenth of these cars were limousines or SUVs.[248]Some 3,300 taxis are also licensed to operate in Cluj-Napoca.[249]

Air[edit]

TheCluj-Napoca International Airport(CLJ), located 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) to the east of the city centre, is the second busiest airport in Romania,[250]after Bucharest'sOTP,handling over 1.4 million passengers in 2015.[251]Situated on theEuropean route E576(Cluj-Napoca–Dej), the airport is connected to the city centre by the local public transport company, CTP, bus number 8 and trolley number 5. The airport serves various direct international destinations across Europe. In 2016, a 42 m-high control tower will be inaugurated on the site of the old tower, built in the 1960s.[252]The new control tower will be one of the most modern in the country.[253]

Rail[edit]

Cluj-Napoca Rail Station,located about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north of the city centre, is situated on theCFR-Romanian RailwaysMain Line 300 (Bucharest–Oradea– Romanian Western Border) and on Line 401 (Cluj-Napoca –Dej). CFR provides direct rail connections to all the major Romanian cities and toBudapest.The rail station is very well connected to all parts of the city by the trams,trolleybusesand buses of the local public transport company, CTP.

The city is also served by two other secondary rail stations, theLittle Station(Gara Mică), which is technically part of and situated immediately near the main station, andCluj-Napoca East(Est). There is also a cargo station,Halta "Clujana".

Public transport[edit]

CTP,the local public transport company, runs an extensive 321 kilometres (199 mi) public transport network within the city using 3 tram lines, 6trolleybuslines and 21 bus routes.[79]Transport in the Cluj-Napoca metropolitan area is also covered by a number of private bus companies, such as Fany and MV Trans 2007, providing connections to neighboring towns and villages.[254]

Trams[edit]

The local transportation company, CTP, manages a tram line that runs through the city. Planned modernisation will involve the installation of new rail tracks and the separation of the tram route from road traffic. This will bring a number of advantages, including vibration and shock reduction, a substantial noise decrease, long use expectancy and highertransitspeed – 60 to 80 km/h (37 to 50 mph).[255]The route will undergo major alteration on Horea Street, between theChamber of Commerceand the central rail station, a rather problematic area. This dilemma should be solved either with the relocation of the track next to the sidewalk, or through the construction of a suspended tunnel.[256]Another area that will benefit from large-scale changes is "Splaiul Independenței", where the tracks will be pulled back to theCentral Park,so that the roadway can host two lanes. In the Mănăștur area, under the bridge, the tracks will be brought closer, while other major works will executed on the traffic circle on Primăverii Street. Given the development of themetropolitan area,further plans feature the creation of alight railtrack betweenGilăuandJucuthat will use these modernised tracks in the city.[257]

Metro[edit]

In late 2018, studies began for a proposedCluj-Napoca Metro,[258]continuing into 2020.[259]In February 2023, the design and execution works for Line I of the metro were awarded to theGülermak–Alstom Transport– Arcada Company. The total duration of the contract is estimated at 96 months.[260]

Culture and media[edit]

Cluj-Napoca is an important centre forTransylvanianmass media, since it is the headquarters of all regional television networks, newspapers and radio stations. The largest daily newspapers published inBucharestare usually reissued from Cluj-Napoca in a regional version, covering Transylvanian issues. Such newspapers includeRomânia Liberă,Gardianul,[261]Ziarul Financiar,ProSportandGazeta Sporturilor.Ringieredited a regional version ofEvenimentul Zileiin Cluj-Napoca until 2008, when it decided to close this enterprise.[262]

Apart from the regional editions, which are distributed throughoutTransylvania,the national newspaperZiuaalso runs a local franchise,Ziua de Cluj,that acts as a local daily, available only within city limits. Cluj-Napoca also boasts other newspapers of local interest, likeFăcliaandMonitorul de Cluj,as well as two free dailies,Informația ClujandCluj Expres.Clujeanul,the first of a series of local weeklies edited by the media trustCME,is one of the largest newspapers in Transylvania, with an audience of 53,000 readers per edition.[263]This weekly has a daily online version, entitledClujeanul, ediție online,updated on a real-time basis. Cluj-Napoca is also the centre of the RomanianHungarian languagepress. The city hosts the editorial offices of the two largest newspapers of this kind,KrónikaandSzabadság,[264]as well as those of the magazinesErdélyi NaplóandKorunk.Săptămâna Clujeanăis an economic weekly published in the city, that also issues two magazines on successful local people and companies (Oameni de SuccesandCompanii de Succes) every year, whilePiața A-Zis a newspaper for announcements and advertisements distributed throughout Transylvania. Cluj had an active press in the interwar period as well: publications included theZionistnewspaperÚj Kelet,the official party organsKeleti Újság(for theMagyar Party) andPatria(for theNational Peasants' Party);[265]and the nationalistConștiința RomâneascăandȚara Noastră,the latter a magazine directed byOctavian Goga.[266]Under Communism, publications included the socio-political and literary magazinesTribuna,Steaua,Utunk,Korunk,NapsugárandElőreas well as the regional Communist party daily organsFăcliaandIgazságand the trilingual student magazineEchinox.[267][268]

Among the local television stations in the city,TVR Cluj(public) andOne TV(private) broadcast regionally, while the others are restricted to the metropolitan area.Napoca Cable Networkis available through cable, and broadcasts local content throughout the day. Other stations work as affiliates of national TV stations, only providing the audience with local reports in addition to the national programming. This situation is mirrored in the radio broadcasting companies: except forRadio Cluj,Radio Impulsand the Hungarian-languagePaprika Rádió,all other stations are local affiliates of the national broadcasters.Casa Radio,situated on Donath Street, is one of the modern landmarks of the media and communications industry; it is, however, not the only one:Palatul Telefoanelor( "the telephone palace" ) is also a major modernist symbol of communications in the city centre.[citation needed]

Magazines published in Cluj-Napoca includeHR Journal,a publication discussing human resources issues,J'Adore,a local shopping magazine that is also franchised in Bucharest,Maximum Rock Magazine,dealing with the rock music industry,RDV,a national hunting publication andCluj-Napoca WWW,an English-language magazine designed for tourists. Cultural and social events as well as all other entertainment sources are the leading subjects of such magazines asȘapte SeriandCJ24FUN.

In the early 20th century, film production in Kolozsvár, led byJenő Janovics,was the chief alternative to Budapest.[180]The first film made in the city, in association with the Parisian producerPathé,wasSárga csikó( "Yellow Foal", 1912), based on a popular "peasant drama".Yellow Foalbecame the first worldwide Hungarian success, distributed abroad under the titleThe Secret of the Blind Man:137 prints were sold internationally and the movie was even screened in Japan.[180]

The first artistically prestigious film in the annals of Hungarian cinematography was also produced on this site, based on a national classic,Bánk bán(1914), a tragedy written byJózsef Katona.[180]

Later, the city was the production site of the 1991 Romanian dramaUndeva în Est( "Somewhere in the East" ),[269]and the 1995 Hungarian language filmA Részleg( "Outpost" ).[270]Moreover, the Romanian-language filmCartier( "Neighbourhood", 2001) and its sequelÎnapoi în cartier( "Back to the Neighbourhood", 2006) both feature a story replete with violence and rude language, behind the blocks in the city'sMănășturdistrict.[271]This district is also mentioned in the lyrics to the songÎnapoi în cartierbyLa Familiamember Puya, featured on the soundtrack of the motion picture.

Documentary and mockumentary productions set in the city includeIrshad Ashraf'sSt. Richard of Austin,a tribute to the American film directorRichard Linklater,[272]andCluj-Napocolonia,a mockumentary imagining a fabulous city of the future.[273]

Education[edit]

Higher education has a long tradition in Cluj-Napoca. TheBabeș-Bolyai University(UBB) is the largest in the country, with approximately 50,000 students[274]attending various specialisations inRomanian,Hungarian,German and English. Its name commemorates two importantTransylvanianfigures, the Romanian physicianVictor Babeșand the Hungarian mathematicianJános Bolyai.The university claims roots as far back as 1581, when aJesuitcollege opened in Cluj, but it was in 1872 that emperorFranz Josephfounded the University of Cluj, later renamed theFranz Joseph University(József Ferenc Tudományegyetem).[275]During 1919, immediately after the end of World War I, the university was moved toBudapest,where it stayed until 1921, after which it was moved to the Hungarian city ofSzeged.Briefly, it returned to Cluj in the first half of the 1940s, when the city came back under Hungarian administration, but it was again relocated in Szeged, following the reincorporation of Cluj into Romanian territory. The Romanian branch acquired the nameBabeș;a Hungarian university,Bolyai,was established in 1945, and the two were merged in 1959. The city also hosts nine other universities, among them theTechnical University,theIuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy,theUniversity of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca(USAMV), theUniversity of Arts and Design,theGheorghe Dima Music Academyand other private universities and educational institutes.[citation needed]