Convoy PQ 8

| Convoy PQ 8 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part ofArctic Convoysof theSecond World War | |||||||

The Norwegian and the Barents seas, site of the Arctic convoys | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Escorts: L. S. Saunders Convoy: R. W. Brundle |

Hans-Jürgen Stumpff Hermann Böhm | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 destroyer sunk 1 merchantman damaged | |||||||

Convoy PQ 8(8–17 January 1942) was anArctic convoyof theWestern Alliesto aid theSoviet Unionduring theSecond World War.The convoy leftIcelandon 8 January 1942. On 12 January the convoy had to turn south to avoid ice; the weather was calm, visibility was exceptional, with a short period of twilight around noon. and arrived inMurmansknine days later.

Having ignored earlier convoys, the Germans had begun to reinforce their forces in Norway and assembled the first U-boatwolfpackin the Arctic against PQ 8. On 17 January,U-454of wolfpackUlandamaged the merchant ship SSHarmatrisand sank the destroyerHMSMatabelewith the loss of all but two of its crew, when the convoy had almost reached Murmansk. The rest of the convoy reached Murmansk that day;Harmatriswas towed into harbour on 20 January.

Harmatriswas stranded in Russia by the winter weather, a lack of labour to repair the torpedo damage, frequent air attacks on Murmansk by theLuftwaffeand the cessation of convoys after the disaster ofConvoy PQ 17.Harmatrissailed for Archangelsk on 21 July Not untilConvoy QP 14(13–26 September 1942) wasHarmatrisable to make the return journey.

Background

[edit]Lend-lease

[edit]

AfterOperation Barbarossa,the German invasion of theUSSR,began on 22 June 1941, the UK and USSR signed an agreement in July that they would "render each other assistance and support of all kinds in the present war against Hitlerite Germany".[1]Before September 1941 the British had dispatched 450 aircraft, 22,000 long tons (22,000 t) of rubber, 3,000,000 pairs of boots and stocks of tin, aluminium, jute, lead and wool. In September British and US representatives travelled to Moscow to study Soviet requirements and their ability to meet them. The representatives of the three countries drew up a protocol in October 1941 to last until June 1942 and to agree new protocols to operate from 1 July to 30 June of each following year until the end of Lend-Lease. The protocol listed supplies, monthly rates of delivery and totals for the period.[2]

The first protocol specified the supplies to be sent but not the ships to move them. The USSR turned out to lack the ships and escorts and the British and Americans, who had made a commitment to "help with the delivery", undertook to deliver the supplies for want of an alternative. The main Soviet need in 1941 was military equipment to replace losses because, at the time of the negotiations, two large aircraft factories were being moved east from Leningrad and two more from Ukraine. It would take at least eight months to resume production, until when, aircraft output would fall from 80 to 30 aircraft per day. Britain and the US undertook to send 400 aircraft a month, at a ratio of three bombers to one fighter (later reversed), 500 tanks a month and 300Bren gun carriers.The Anglo-Americans also undertook to send 42,000 long tons (43,000 t) of aluminium and 3, 862 machine tools, along with sundry raw materials, food and medical supplies.[2]

British grand strategy

[edit]

The growing German air strength in Norway and increasing losses to convoys and their escorts, led Rear-AdmiralStuart Bonham Carter,commander of the18th Cruiser Squadron,Admiral sirJohn Tovey,Commander in ChiefHome Fleetand Admiral SirDudley PoundtheFirst Sea Lord,the professional head of theRoyal Navy,unanimously to advocate the suspension of Arctic convoys during the summer months.[3]

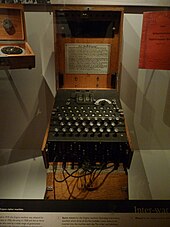

Bletchley Park

[edit]The BritishGovernment Code and Cypher School(GC&CS) based atBletchley Parkhoused a small industry of code-breakers andtraffic analysts.By June 1941, the GermanEnigmamachine Home Waters (Heimish) settings used by surface ships and U-boats could quickly be read. On 1 February 1942, the Enigma machines used in U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean were changed but German ships and the U-boats in Arctic waters continued with the olderHeimish(Hydrafrom 1942, Dolphin to the British). By mid-1941, BritishY-stationswere able to receive and readLuftwaffeW/Ttransmissions and give advance warning ofLuftwaffeoperations. In 1941, navalHeadachepersonnel with receivers to eavesdrop onLuftwaffewireless transmissions were embarked on warships.[4]

B-Dienst

[edit]The rival GermanBeobachtungsdienst(B-Dienst,Observation Service) of theKriegsmarineMarinenachrichtendienst(MND,Naval Intelligence Service) had broken several Admiralty codes and cyphers by 1939, which were used to helpKriegsmarineships elude British forces and provide opportunities for surprise attacks. From June to August 1940, six British submarines were sunk in the Skaggerak using information gleaned from British wireless signals. In 1941,B-Dienstread signals from the Commander in Chief Western Approaches informing convoys of areas patrolled by U-boats, enabling the submarines to move into "safe" zones.[5]B-Diensthad broken Naval Cypher No 3 in February 1942 and by March was reading up to 80 per cent of the traffic, which continued until 15 December 1943. By coincidence, the British lost access to theSharkcypher and had no information to send in Cypher No 3 which might compromise Ultra.[6]In early September,Finnish Radio Intelligencedeciphered a Soviet Air Force transmission which divulged the convoy itinerary, which was forwarded it to the Germans.[7]

Arctic Ocean

[edit]

Between Greenland and Norway are some of the most stormy waters of the world's oceans, 890 mi (1,440 km) of water under gales full of snow, sleet and hail.[8]The cold Arctic water was met by theGulf Stream,warm water from theGulf of Mexico,which became theNorth Atlantic Drift.Arriving at the south-west of England the drift moves between Scotland and Iceland; north of Norway the drift splits. One stream bears north ofBear IslandtoSvalbardand a southern stream follows the coast of Murmansk into the Barents Sea. The mingling of cold Arctic water and warmer water of higher salinity generates thick banks of fog for convoys to hide in but the waters drastically reduced the effectiveness ofASDICas U-boats moved in waters of differing temperatures and density.[8]

In winter, polar ice can form as far south as 50 mi (80 km) off the North Cape and in summer it can recede to Svalbard. The area is in perpetual darkness in winter and permanent daylight in the summer and can make air reconnaissance almost impossible.[8]Around theNorth Capeand in theBarents Seathe sea temperature rarely rises about 4°Celsiusand a man in the water will die unless rescued immediately.[8]The cold water and air makes spray freeze on the superstructure of ships, which has to be removed quickly to avoid the ship becoming top-heavy. Conditions in U-boats were, if anything, worse the boats having to submerge in warmer water to rid the superstructure of ice. Crewmen on watch were exposed to the elements, oil lost its viscosity, nuts froze and sheared off. Heaters in the hull wee too demanding of current and could not be run continuously.[9]

Prelude

[edit]Kriegsmarine

[edit]German naval forces in Norway were commanded byHermann Böhm,theKommandierender Admiral Norwegen.Two U-boats were based in Norway in July 1941, four in September, five in December and four in January 1942.[10]By mid-February twenty U-boats were anticipated in the region, with six based in Norway, two inNarvikorTromsø,two atTrondheimand two at Bergen. Hitler contemplated establishing a unified command but decided against it. The German battleshipTirpitzarrived at Trondheim on 16 January, the first ship of a general move of surface ships to Norway. British convoys to Russia had received little attention since they averaged only eight ships each and the long Arctic winter nights negated even the limitedLuftwaffeeffort that was available.[11]

Luftflotte5

[edit]

In mid-1941,Luftflotte 5(Air Fleet 5) had been re-organised for Operation Barbarossa withLuftgau Norwegen(Air Region Norway) was headquartered inOslo.Fliegerführer Stavanger(Air CommanderStavanger) the centre and north of Norway,Jagdfliegerführer Norwegen(Fighter Leader Norway) commanded the fighter force andFliegerführer Kerkenes(Oberst[colonel] Andreas Nielsen) in the far north had airfields atKirkenesandBanak.The Air Fleet had 180 aircraft, sixty of which were reserved for operations on theKarelian Frontagainst theRed Army.The distance from Banak toArchangelskwas 560 mi (900 km) andFliegerführer Kerkeneshad only tenJunkers Ju 88bombers ofKampfgeschwader 30,thirtyJunkers Ju 87Stukadive-bombers tenMesserschmitt Bf 109fighters ofJagdgeschwader 77,fiveMesserschmitt Bf 110heavy fighters ofZerstörergeschwader 76,ten reconnaissance aircraft and an anti-aircraft battalion.[12]

Sixty aircraft were far from adequate in such a climate and terrain where "there is no favourable season for operations". The emphasis of air operations changed from army support to anti-shipping operations as Allied Arctic convoys became more frequent.[12]Hubert Schmundt,theAdmrial Nordmeernoted gloomily on 22 December 1941 that the number long-range reconnaissance aircraft was exiguous and from 1 to 15 December only two Ju 88 sorties had been possible. After the Lofoten Raids, Schmundt wantedLuftflotte 5to transfer aircraft to northern Norway but its commander,GeneraloberstHans-Jürgen Stumpff,was reluctant to deplete the defences of western Norway. Despite this some air units were transferred, a catapult ship (Katapultschiff),MSSchwabenland,was sent to northern Norway andHeinkel He 115floatplane torpedo-bombers, ofKüstenfliegergruppe1./406 was transferred toSola.By the end of 1941, III Gruppe, KG 30 had been transferred to Norway and in the new year, anotherStaffelof Focke-Wulf Fw 200KondorsfromKampfgeschwader 40(KG 40) had arrived.Luftflotte 5Was also expected to receive aGruppecomprising threeStaffelnofHeinkel He 111torpedo-bombers.[13]

Air-sea rescue

[edit]

TheLuftwaffe Sea Rescue Service(Seenotdienst) along with theKriegsmarine,theNorwegian Society for Sea Rescue(RS) and ships on passage, recovered aircrew and shipwrecked sailors. The service comprisedSeenotbereich VIIIat Stavanger, covering Bergen and Trondheim withSeenotbereich IXat Kirkenes for Tromsø, Billefjord and Kirkenes. Co-operation was as important in rescues as it was in anti-shipping operations if people were to be saved before they succumbed to the climate and severe weather. The sea rescue aircraft comprisedHeinkel He 59floatplanes,Dornier Do 18andDornier Do 24seaplanes.[14]Oberkommando der Luftwaffe(OKL, the high command of the Luftwaffe) was not able to increase the number ofsearch and rescueaircraft in Norway, due to a general shortage of aircraft and crews, despite Stumpff pointing out that coming down in such cold waters required extremely swift recovery and that his crews "must be given a chance of rescue" or morale could not be maintained.[14]

Arctic convoys

[edit]A convoy was defined as at least one merchant ship sailing under the protection of at least one warship.[15]At first the British had intended to run convoys to Russia on a forty-day cycle (the number of days between convoy departures) during the winter of 1941–1942 but this was shortened to a ten-day cycle. The round trip to Murmansk for warships was three weeks and each convoy needed a cruiser and two destroyers, which severely depleted the Home Fleet. Convoys left port and rendezvoused with the escorts at sea. A cruiser provided distant cover from a position to the west of Bear Island. Air support was limited to330 Squadronand269 Squadron,RAF Coastal CommandfromIceland,with some help from anti-submarine patrols from Sullom Voe, inShetland,along the coast of Norway.Anti-submarine trawlersescorted the convoys on the first part of the outbound journey. Built for Arctic conditions, the trawlers were coal-burning ships with sufficient endurance. The trawlers were commanded by their peacetime crews and captains with the rank ofSkipper,Royal Naval Reserve(RNR), who were used to Arctic conditions, supplemented by anti-submarine specialists of theRoyal Naval Volunteer Reserve(RNVR).[16]British minesweepers based at Archangelsk met the convoys to join the escort for the remainder of the voyage.[17]

By late 1941, the convoy system used in the Atlantic had been established on the Arctic run; aconvoy commodoreensured that the ships' masters and signals officers attended a briefing to make arrangements for the management of the convoy, which sailed in a formation of long rows of short columns. The commodore was usually a retired naval officer or from the Royal Naval Reserve and would be aboard one of the merchant ships (identified by a white pendant with a blue cross). The commodore was assisted by a Naval signals party of four men, who used lamps,semaphore flagsand telescopes to pass signals in code. The codebooks were carried in a weighted bag which was to be dumped overboard to prevent capture. In large convoys, the commodore was assisted by vice- and rear-commodores with whom he directed the speed, course and zig-zagging of the merchant ships and liaised with the escort commander.[18]

In October 1941, the Prime Minister,Winston Churchill,made a commitment to send a convoy to the Arctic ports of the USSR every ten days and to deliver1,200 tanksa month from July 1942 to January 1943, followed by2,000 tanksand another3,600 aircraftin excess of those already promised.[1][a]The first convoy was due at Murmansk around 12 October and the next convoy was to depart Iceland on 22 October. A motley of British, Allied and neutral shipping, loaded with military stores and raw materials for the Soviet war effort would be assembled atHvalfjörður(Hvalfiord) inIceland,convenient for ships from both sides of the Atlantic.[20]

By the end of 1941, 187Matilda IIand 249Valentine tankshad been delivered, comprising 25 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks in the Red Army and 30 to 40 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks defending Moscow. In December 1941, 16 per cent of the fighters defending Moscow wereHawker HurricanesandCurtiss Tomahawksfrom Britain; by 1 January 1942, 96 Hurricane fighters were flying in theSoviet Air Forces(Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily,VVS). The British supplied radar apparatuses, machine tools, ASDIC and other commodities.[21]During the summer months, convoys went as far north as 75 N latitude then south into the Barents Sea and to the ports of Murmansk in theKola Inletand Archangel in theWhite Sea.In winter, due to thepolar iceexpanding southwards, the convoy route ran closer to Norway.[22]The voyage was between 1,400 and 2,000 nmi (2,600 and 3,700 km; 1,600 and 2,300 mi) each way, taking at least three weeks for a round trip.[23]

Convoy PQ 8

[edit]

PQ 8 consisted of eight merchant ships; theBritishtankersBritish PrideandBritish Workmanand the British merchant shipsDartford,SouthgateandHarmatris(ship of the convoy commodore, R. W. Brundle), theSovietStarii Bolshevik,Larranga,the firstUSship on the Arctic run andEl Almirantea US ship ofPanamanianregistry. The convoy sailed fromLoch EweinWester Ross,Scotland, an anchorage large enough to accommodate forty ships.[24]The convoy sailed for Hvalfjörður (Hvalfiord) in Iceland on 28 December 1941.[25]Convoys had a standard formation of short columns, number 1 to the left in the direction of travel.[26][b]

Ships in column sailed at intervals of 400 yd (370 m) until 1943 when the interval was increased to 600 yd (550 m) then 800 yd (730 m) to cater for inexperienced captains reluctant to keep so close.[28]PQ 8 had a close escort of two minesweepers,HMSHarrier(Lieutenant-Commander E. P. Hinton) andSpeedwell(Lieutenant-Commander J. J. Youngs) and arrived at Hvalfiord on 1 January 1942 at8:20 p.m.,Brundle being re-appointed convoy commodore for the voyage to Russia.[29][30]On 11 January, the convoy rendezvoused with the ocean escort comprising the destroyersHMSMatabeleandSomaliand the cruiserHMSTrinidad(Captain L. S. Saunders).[31]

Voyage

[edit]8–16 January

[edit]PQ 8 sailed from Hvalfjörður on 8 January 1942 and was joined on the night of 10/11 January in fine weather by the ocean escort, which had sailed from Scapa flow and re-fuelled atSeidisfiordon 9 January. On 12 January the convoy reached73°45′N00°00′E/ 73.750°N 0.000°Eand had to turn south to avoid ice; the weather remained calm and visibility was exceptional, with a short period of twilight around noon.Trinidadmade several departures from the convoy for training.[29]TheKriegsmarinehad establishedUlanits first Arcticwolfpack,a patrol line consisting of theU-boatsU-134(Rudolf Schendel),U-454(Burckhard Hacklander) andU-584(Joachim Deecke), based at Kirkenes, searched for the convoy.[32]

17 January

[edit]

In the continuous darkness of thepolar night,German reconnaissance aircraft and U-boats failed to find PQ 8. On 17 January, the convoy was heading south at 8 kn (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) withHarrierahead,Triinidadoff the starboard bow ofHarmatrisat the head of the third column (position 31) and the destroyers 1 nmi (1.9 km; 1.2 mi) distant on each flank,Speedwellfollowing on behind. A junction with the Murmansk-based minesweepers was made difficult by fog;HMSBritomartandSalamanderwere stuck in the Kola Inlet butSharpshootersailed, followed a while later byHazard.[29]

The Russian trawler RT-68Enisej(557 GRT), sailing independently, was attacked at about6:00 a.m.byU-454(KapitänleutnantBurkhard Hackländer) with two torpedoes which missed but at6:32 a.m.a third torpedo sank the boat; two men were killed and 34 survived, their lifeboat reaching the shore.[33]At 7:45 p.m.,U-454found PQ 8 and fired a torpedo at the merchant shipHarmatris,which exploded in No. 1 hold on the starboard side. Brundle was off the bridge and the First Mate, George Masterman, promptly ordered the ship stopped, to prevent its forward motion from driving the ship under water. The crew was ordered to boat stations; luckily the torpedo warheads in No. 1 hold had fallen through the hole in the hull without detonating. FromTrinidadit looked as ifHarmatrishad hit a mine butMatabelereported hearing a torpedo on its hydrophones.[34]

The destroyers conducted an abortive anti-submarine sweep andSpeedwelldropped back to stand near the ship. As the rest of the convoy sailed past in line, the vice-commodore onLarrangatook over the convoy. An hour later the ship shook and Brundle thought it was a mine explosion but U-454 had manoeuvred round and hitHarmatrison the port side with a torpedo that failed to explode.Speedwellcame alongside and took off the crew. During the night, asHarmatrissettled at the bow and its propeller rose out of the sea, Brundle thought thatHarmatriscould be towed and having persuaded Lieutenant-Commander Youngs, the captain ofSpeedwell,to attempt a tow, asked for volunteers; all of the crew offered to re-board the ship and were promptly transferred. Eventually a cable was passed toHarmatrisbut the towing sweeps soon snapped. The starboard anchor was found to have been dislodged by the torpedo and was dragging along the seabed 90 fathoms (540 ft; 160 m) below.[35]At10:00 p.m.TrinidadsentMatabeleback toHarmatrisasSharpshooterhad arrived from Kola at9:45 p.m.[34]

U-454had sailed ahead of the ships and saw the tankerBritish Prideilluminated by the lighthouse at Cape Teriberskiy and fired a salvo of torpedoes. The torpedoes missed the tanker but one hitMatabelewhich exploded. Only two men, Ordinary Seamen William Burras and Ernest Higgins survived, the crew being killed in the torpedo explosion, the detonation of its depth charges or of hypothermia in the water.[36][c]The convoy scattered, the escorts roving around them until the seven undamaged ships returned to line ahead and resumed course.Somalimade a wide circuit 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) around the starboard side of the convoy and depth-charged several Asdic contacts.U-454had descended almost to the sea bed and depth charges fromSomaliexploded above it without effect.[36]

18–19 January

[edit]OnHarmatristhewindlasshad been damaged in the explosion and was jammed, the anchor cable would have to be cut by hand. Youngs, onSpeedwell,suggested that the crew ofHarmatrisshould return and the crew spent the night onSpeedwell,returning at6:00 a.m.The crew found that the steam pipes had frozen; the steam had been left on, emptying the boilers and work on splitting the anchor cable had to resume by hand. Eventually the cable parted and cables were passed toHarmatris.At8:00 a.m.,Speedwellbegan the tow.SharpshooterandHazardof the Eastern Local Escort had joined the two ships and around noon, about 8 nmi (15 km; 9.2 mi) from Cape Teriberski, as the sky lightened, a He 111 bomber attacked the ships. TheLuftflotte5 had been reinforced and now had 230 aircraft, based at airfields in northern Norway and at Petsamo in Finland.[37]

The HeinkelstrafedHarmatrisat low altitude but was hit and driven off, trailing smoke, by the anti-aircraft fire of the minesweepers and the eightDefensively equipped merchant ship(DEMS) gunners on board. Brundle tried to fire hisParachute and Cablerockets but they had frozen. A Junkers Ju 88 attacked about an hour later, straddled the ship with bombs, which caused no damage and turned away, also trailing smoke, leaving bullet holes in the superstructure. (At Murmansk, Youngs said that the Heinkel had crashed and that the Russians had credited the two ships with the victory.) At2:30 p.m.a steam pipe onSpeedwellburst, severely injuring three men and Youngs called for a Soviet tug, which arrived quickly, taking over the tow asSpeedwellraced for port to get the injured into hospital. Two more tugs arrived at5:00 p.m.on 19 January.[38]

20 January

[edit]The German navy had planned to attack the convoy with thebattleshipTirpitzbut lack of fuel and insufficientdestroyerescorts, due to them being diverted in support of theChannel Dash,forced a cancellation of the attack.[39]Another two tugs arrived and helped guideHarmatrisinto Murmansk, down at the bow with its propeller out of the water, at2:00 p.m.on 20 January.[40]The crew surveyed the ship and found that iron locking bars had been scattered about the deck and wooden hatched and tarpaulins were trapped in the rigging. Much of the interior was waterlogged, number 1 hold being almost full of water and the forward bulkhead had been broken along with the forepeak tank and the fore and aft bulkhead.[41]

Aftermath

[edit]Analysis

[edit]While PQ 8 had sailed to Murmansk,Convoy QP 5comprisingArcos,Dekabrist,EulimaandSan Ambrosiohad departed for Iceland on 13 January, escorted by the cruiserHMSCumberlandand the destroyersIcarusandTartararriving safely on 24 January.[42]Despite the loss ofMatabele,PQ 8 had been fortunate that a sortie byTirpitzhad been cancelled, due to its destroyer escorts being diverted south for the Channel Dash. The regular sailings to Murmansk and the failure of the German Army to capture the port six months after the start of Operation Barbarossa, made the establishment of a U-boat force in Norway permanent and become a significant part of the anti-shipping effort.[43]

Subsequent operations

[edit]The next convoy, the combined PQ 9 and PQ 10 (ten ships) and PQ 11 (13 ships) slipped past the German defences unscathed but the increasing hours of daylight made further convoys more vulnerable, when it would be another eight to twelve weeks before the pack ice receded. Tovey thought that it was wrong for U-boats to be able to lie in wait off the Kola Inlet. In Tovey's view the Russians should be able to make these waters too dangerous for U-boats and provide fighter cover to convoys as they approached their destination. In February, Rear-AdmiralHarold Burrough,commander of the10th Cruiser Squadron,was despatched to Murmansk inHMSNigeriato represent Tovey's views that the Russians should make more effort to defend convoys between Bear Island and the Kola Inlet.[44]

Harmatris

[edit]Harmatrishad reached Murmansk but the crew found that it was ill-equipped to handle the number of ships or the quantity of cargo to be unloaded. The two tankers passed highly volatile aviation spirit straight into railway tankers on the jetty, risky in itself and worse during the frequent Luftwaffe air raids on the port. (After Stalingrad Murmansk was the most bombed city of the Soviet Union). Discharge facilities were lacking, despite the development of the port since theFirst World War.Work began as soon asHarmatrisberthed to get the ice out of the steam pipes, which took three days. With steam up, the cargo could be unloaded, which took until 4 February, most of the cargo being undamaged. Two of the fifteen lorries in No. 1 hold were write-offs and 750 long tons (760 t) of sugar was lost. On 5 February the ship was ordered to quay 6, to await dry-docking. The ship had a severe list to starboard but there was little steam to get the ice and snow off the deck, because only sufficient steam pipes to unload had been cleared. To make matters worse, a fire began in the stokehold ashes, which heated the bulkhead of the cadets' room to red hot and caused their wardrobe to burn along with the cadets' clothes, two hours' work being needed to put out the fire.Harmatriswent into dry-dock on 10 February, down 21 ft (6.4 m) at the head and up 11 ft (3.4 m) at the stern.[45]

There was a hole about 60 by 30 ft (18.3 by 9.1 m) on the starboard side, the No. 1 ballast tank had been destroyed and the bulkheads were damaged. On the port side there was a big bulge about 14 ft (4.3 m) wide, rivets had popped and the decks and other parts of the superstructure were severely damaged. The engine room needed repairs but it was exceedingly difficult to find spare parts or obtain labour because of the shortage. The Captain sent groups of crewmembers to cadge spares from other ships but the shortages and the intense cold stopped work, then Brundle was told thatHarmatriswas being evicted from the dry dock to make room for a destroyer. The Senior British Naval Officer, Rear-AdmiralRichard Bevan,overruled Brundle's objections and on 14 MarchHarmatriswas moved to a coal dock near Vaenga, about 4 mi (6.4 km) from Murmansk. No help was forthcoming from the Russian authorities and the engineers in the crew offered to continue the repair work provided the employer paid overtime. Since the U-boat attack, No. 2 hold had been taking on water which would add to the ship's list; Brundle spent much time telephoning British and Russian agencies to find an electric pump and had to be talked out of writing to Stalin in despair. The ship owners in Britain were informed, who promised help and some Russian labour was provided in the form of 16–18-year old girls.[46]

Murmansk received about three raids a day from theLuftwaffe,whose bases were five minutes' flying time away. A ship was sunk on the night of 3/4 April and one nearby was bombed and set on fire, its cargo being unloaded between air raids and between fire-fighting, then the ship was sunk on 16 June. On 14 April another ship was sunk. Many of the sinkings were fromConvoy PQ 13,two were from were fromConvoy PQ 15andAlcoa Cadetwas sunk by an internal explosion;Steel Workerwas blown up on a mine. The crew ofHarmatrisdecided to work at night and sleep by day onshore. While at Murmansk the dock was attacked thirty times,Harmatrisbeing rained with bomb splinters and shuddering from nearby bomb explosions. There was an acute food shortage, adults being rationed to 11 oz (300 g) and crew fromHarmatrisrowed out to ships sunk in shallow water to recover tinned food; a ship from the parent company brought more food.Harmatrissailed for Archangelsk on 21 July, a 400 nmi (740 km; 460 mi) journey completed on 24 July. On 26 July the ship moved to Ekonomiya to discharge ballast and took on 3,000 long tons (3,000 t) of steel pipe at Myrmaxa. There was a food shortage at Archangelsk and the merchant captains kept in touch to make sure that the crews got their share when food appeared. The port was less frequently bombed than Murmansk and was a gathering point for about survivors, including 141 fromConvoy PQ 17.[47]By SeptemberHarmatrishad taken on twenty survivors and 200 long tons (200 t) of dubious quality coal, ready to sail for Britain, departing on 13 September inConvoy QP 14.[48]

List of ships

[edit]Merchant ships

[edit]| Ship | Year | Flag | GRT | No.[d] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Pride | 1931 | 7,106 | 22 | Tanker, arrived on 17 January | |

| British Workman | 1922 | 6,994 | 32 | Tanker, arrived on 17 January | |

| Dartford | 1930 | 4,093 | 12 | Arrived on 17 January | |

| El Almirante | 1917 | 5,248 | 11 | Arrived on 17 January | |

| Harmatris | 1932 | 5,395 | 31 | Convoy Commodore; torpedoed, towed to port bySpeedwelland Soviet tugs, arrived 20 January[50] | |

| Larranga | 1917 | 3,804 | 21 | Vice-Convoy Commodore took over fromHarmatris,arrived 17 January | |

| Southgate | 1926 | 4,862 | 41 | Arrived on 17 January | |

| Starii Bolshevik | 1933 | 3,974 | 42 | Arrived on 17 January |

Escorts

[edit]| Name | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMSHarrier | Minesweeper | Escort 8–17 January | |

| HMSHazard | Minesweeper | Escort 16–17 January | |

| HMSMatabele | Destroyer | Escort 11–17 January, sunk byU-454at69°21′N35°34′E/ 69.350°N 35.567°E,two survivors[51] | |

| HMSSharpshooter | Minesweeper | Escort 16–17 January | |

| HMSSomali | Destroyer | Escort 11–17 January | |

| HMSSpeedwell | Minesweeper | Escort 8–17 January | |

| HMSTrinidad | Cruiser | Escort 11–17 January |

Notes

[edit]- ^In October 1941, the unloading capacity of Archangel was 300,000 long tons (300,000 t), Vladivostok (Pacific Route) 140,000 long tons (140,000 t) and 60,000 long tons (61,000 t) in the Persian Gulf (for thePersian Corridorroute) ports.[19]

- ^Each position in the column was numbered; 11 was the first ship in column 1 and 12 was the second ship in the column; 21 was the first ship in column 2.[27]

- ^Higgins had been ordered to close the magazine hatches and then tried to release theCarley floatsbut they were iced solid and he was told to go forward and close more hatches but the magazine exploded and broke the ship in two. Higgins had to jump into the water amidst many other crewmen, trying to swim away from the wreck before it sank. Some men called for help and others succumbed to the cold but Higgins saw a coiled boarding net; with Burras, Higgins swam for it but the cold made them slip into semi-consciousness.Somali,on the far side of the convoy, increased speed to 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph) and crossed the bows ofBritish Prideat the moment thatMatabeleexploded. Captain Bain, the Senior Escort Commander, realised thatMatabelewas beyond help and orderedHarrierto the rescue. Many bodies of the crew were taken out of the water by the crew ofHarrier;Burras and Higgins were pulled from the sea covered in fuel oil, which probably insulated them from the cold. One of the survivors thought that 50 to 60 men had gone into the water.[36]

- ^Convoys had a standard formation of short columns, number 1 to port in the direction of travel. Each position in the column was numbered; 11 was the first ship in column 1 and 12 was the second ship in the column; 21 was the first ship in column 2.[27]

- ^Data taken from Ruegg and Hague (1993) unless indicated.[49]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^abWoodman 2004,p. 22.

- ^abHancock & Gowing 1949,pp. 359–362.

- ^Woodman 2004,pp. 144–145.

- ^Macksey 2004,pp. 141–142;Hinsley 1994,pp. 141, 145–146.

- ^Kahn 1973,pp. 238–241.

- ^Budiansky 2000,pp. 250, 289.

- ^FIB 1996.

- ^abcdClaasen 2001,pp. 195–197.

- ^Paterson 2016,pp. 100–101.

- ^Rahn 2001,p. 348.

- ^Claasen 2001,pp. 190–192, 194.

- ^abClaasen 2001,pp. 188–189.

- ^Claasen 2001,pp. 189–194.

- ^abClaasen 2001,pp. 203–205.

- ^Roskill 1957,p. 92.

- ^Woodman 2004,p. 44.

- ^Roskill 1957,pp. 92, 492.

- ^Woodman 2004,pp. 22–23.

- ^Howard 1972,p. 44.

- ^Woodman 2004,p. 14.

- ^Edgerton 2011,p. 75.

- ^Roskill 1962,p. 119.

- ^Butler 1964,p. 507.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,pp. 56, 61.

- ^Roskill 2004,p. 432.

- ^Woodman 2004,p. 104;Ruegg & Hague 1993,p. 31, inside front cover.

- ^abRuegg & Hague 1993,p. 31, inside front cover.

- ^Hague 2000,p. 27.

- ^abcWoodman 2004,p. 56.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,p. 66.

- ^Ruegg & Hague 1993,p. 25;Woodman 2004,p. 58.

- ^Woodman 2004,p. 56;Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005,p. 134;Blair 1996,Appendix 5.

- ^Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005,p. 134;Paterson 2016,p. 62.

- ^abWoodman 2004,p. 57.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,pp. 74–75.

- ^abcWadsworth 2009,pp. 77–78.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,pp. 80–81.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,pp. 80–83, 58–59, 85.

- ^Garzke & Dulin 1985,p. 250;Paterson 2016,p. 61.

- ^Woodman 2004,pp. 58–59.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,p. 85.

- ^Woodman 2004,p. 58.

- ^Paterson 2016,pp. 62–63.

- ^Roskill 1962,pp. 119–120.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,pp. 85–87, 95–96.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,pp. 96–97.

- ^Woodman 2004,p. 284.

- ^Wadsworth 2009,pp. 98–101, 116–118, 121.

- ^abRuegg & Hague 1993,p. 25.

- ^Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005,p. 134.

- ^Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005,p. 134;Brown 1995,p. 56.

References

[edit]- Blair, Clay (1996).Hitler's U-Boat War.Vol. I. New York: Random House.ISBN0-304-35260-8.

- Brown, David (1995) [1990].Warship Losses of World War Two(2nd rev. ed.). London: Arms and Armour Press.ISBN978-1-85409-278-6.

- Boog, H.; Rahn, W.; Stumpf, R.; Wegner, B. (2001).The Global War: Widening of the Conflict into a World War and the Shift of the Initiative 1941–1943.Germany in the Second World War. Vol. VI. Translated by Osers, E.; Brownjohn, J.; Crampton, P.; Willmot, L. (Eng trans. Oxford University Press, London ed.). Potsdam: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Research Institute for Military History).ISBN0-19-822888-0.

- Rahn, W. "Part III The War at Sea in the Atlantic and in the Arctic Ocean. III. The Conduct of the War in the Atlantic and the Coastal Area (b) The Third Phase, April–December 1941: The Extension of the Areas of Operations". InBoog et al. (2001).

- Budiansky, S. (2000).Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II.New York: The Free Press (Simon & Schuster).ISBN0-684-85932-7– via Archive Foundation.

- Butler, J. R. M.(1964).Grand Strategy: June 1941 – August 1942 (Part II).History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III. London: HMSO.OCLC504770038.

- Claasen, A. R. A. (2001).Hitler's Northern War: The Luftwaffe's Ill-fated Campaign, 1940–1945.Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.ISBN0-7006-1050-2.

- Edgerton, D.(2011).Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources and Experts in the Second World War.London: Allen Lane.ISBN978-0-7139-9918-1.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985).Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II.Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.ISBN978-0-87021-101-0.

- Hague, Arnold (2000).The Allied Convoy System, 1939–1945: Its Organization, Defence and Operation.Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.ISBN978-1-55750-019-9.

- Hancock, W. K.;Gowing, M. M.(1949). Hancock, W. K. (ed.).British War Economy.History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Civil Series. London: HMSO.OCLC630191560.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993].British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations.History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: HMSO.ISBN978-0-11-630961-7.

- Howard, M.(1972).Grand Strategy: August 1942 – September 1943.History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. London:HMSO.ISBN978-0-11-630075-1– via Archive Foundation.

- Kahn, D. (1973) [1967].The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing(10th abr. Signet, Chicago ed.). New York: Macmillan.LCCN63-16109.OCLC78083316.

- Macksey, K.(2004) [2003].The Searchers: Radio Intercept in two World Wars(Cassell Military Paperbacks ed.). London: Cassell.ISBN978-0-304-36651-4.

- Paterson, Lawrence (2016).Steel and Ice: The U-Boat Battle in the Arctic and Black Sea 1941–45.Stroud: The History Press.ISBN978-1-59114-258-4.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (2005) [1972].Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two(3rd rev. ed.). London: Chatham.ISBN978-1-86176-257-3.

- Roskill, S. W.(1957) [1954].Butler, J. R. M.(ed.).The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Defensive.History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (4th impr. ed.). London: HMSO.OCLC881709135.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2022.

- Roskill, S. W.(1962) [1957].The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Period of Balance.History of the Second World War.Vol. II (3rd impr. ed.). London:HMSO.OCLC174453986.Retrieved4 June2018– via Hyperwar.

- Roskill, S. W. (2004) [1961].The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Offensive Part II 1st June 1944 – 14th August 1945.History of the Second World War. Vol. III (facs. repr. Naval and Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London:HMSO.ISBN978-1-84342-806-0.

- Ruegg, R.; Hague, A. (1993) [1992].Convoys to Russia: Allied Convoys and Naval Surface Operations in Arctic Waters 1941–1945(2nd rev. enl. ed.). Kendal: World Ship Society.ISBN0-905617-66-5.

- Wadsworth, M. (2009).Arctic Convoy PQ 8: The Story of Capt Robert Brundle and the SS Harmatris.Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime.ISBN978-1-84884-051-5.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994].Arctic Convoys 1941–1945.London: John Murray.ISBN978-0-7195-5752-1.

Websites

- "Birth of Radio Intelligence in Finland and its Developer Reino Hallamaa".Pohjois–Kymenlaakson Asehistoriallinen Yhdistys Ry (North-Karelia Historical Association Ry)(in Finnish). 1996.Retrieved26 July2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Kemp, Paul (2000).Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters.London: Cassell.ISBN978-0-30435-451-1.

- Schofield, Bernard (1964).The Russian Convoys.London: BT Batsford.OCLC862623.

- Jordan, Roger W. (2006) [1999].The World's Merchant Fleets 1939: The Particulars and Wartime Fates of 6,000 Ships(2nd ed.). London: Chatham/Lionel Leventhal.ISBN978-1-86176-293-1.