Corinthian order

TheCorinthian order(Greek:Κορινθιακὸς ῥυθμός,Korinthiakós rythmós;Latin:Ordo Corinthius) is the last developed and most ornate of the three principalclassical ordersofAncient Greek architectureandRoman architecture.The other two are theDoric order,which was the earliest, followed by theIonic order.In Ancient Greek architecture, the Corinthian order follows the Ionic in almost all respects, other than the capitals of the columns, though this changed in Roman architecture.[1]

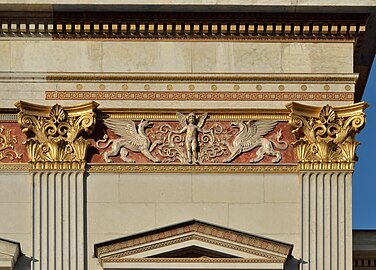

A Corinthian capital may be seen as an enriched development of the Ionic capital, though one may have to look closely at a Corinthian capital to see the Ionicvolutes( "helices" ), at the corners, perhaps reduced in size and importance, scrolling out above the two ranks ofstylized acanthus leavesand stalks ( "cauliculi" orcaulicoles), eight in all, and to notice that smaller volutes scroll inwards to meet each other on each side. The leaves may be quite stiff, schematic and dry, or they may be extravagantly drilled and undercut, naturalistic and spiky. The flatabacusat the top of the capital has a concave curve on each face, and usually a single flower ( "rosette" ) projecting from the leaves below overlaps it on each face.

Whenclassical architecturewas revived during theRenaissance,two more orders were added to thecanon:theTuscan orderand theComposite order,known in Roman times, but regarded as a grand imperial variant of the Corinthian. The Corinthian hasflutedcolumnsand elaboratecapitalsdecorated withacanthusleaves and scrolls. There are many variations.[2]

The nameCorinthianis derived from the ancient Greek city ofCorinth,although it was probably invented inAthens.[3]

Description[edit]

Greek Corinthian order[edit]

The Corinthian order is named for the Greek city-state ofCorinth,to which it was connected in the period. However, according to the architectural historianVitruvius,the column was created by the sculptorCallimachus,probably an Athenian, who drew acanthus leaves growing around a votive basket of toys, with a slab on top, on the grave of a Corinthian girl.[3]

Its earliest use can be traced back to the Late Classical Period (430–323 BC). The earliest Corinthian capitals, already in fragments and now lost, were found inBassaein 1811–12; they are dated around 420 BC, and are in a temple of Apollo otherwise using the Ionic. There were three of them, carrying the frieze across the far end of the cella, which was open to theadytum.The Corinthian was probably devised to solve the awkwardness the Ionic capital created at corners by having clear and distinct front or back and side-on faces,[4]a problem only finally solved byVincenzo Scamozziin the 16th century.

A simplified late version of the Greek Corinthian capital is often known as the "Tower of the Winds Corinthian" after its use on the porches of theTower of the Windsin Athens (about 50 BC). There is a single row ofacanthusleaves at the bottom of the capital, with a row of "tall, narrow leaves" behind.[5]These cling tightly to the swelling shaft, and are sometimes described as "lotus" leaves, as well as the vague "water-leaves" and palm leaves; their similarity to leaf forms on many ancient Egyptian capitals has been remarked on.[6]The form is usually found in smaller columns, both ancient and modern.

Roman Corinthian order[edit]

The style developed its own model in Roman practice, following precedents set by theTemple of Mars Ultorin theForum of Augustus(c. 2 AD).[7]It was employed in southern Gaul at theMaison Carrée,Nîmes and at the comparableTemple of Augustus and LiviaatVienne.Other prime examples noted byMark Wilson Jonesare the lower order of theBasilica Ulpiaand theArch of TrajanatAncona(both of the reign ofTrajan,98–117 AD), theColumn of Phocas(re-erected inLate Antiquitybut 2nd century in origin), and theTemple of BacchusatBaalbek(c. 150 AD).[8]

Proportion is a defining characteristic of the Corinthian order: the "coherent integration of dimensions and ratios in accordance with the principles ofsymmetria"are noted by Mark Wilson Jones, who finds that the ratio of total column height to column-shaft height is in a 6:5 ratio, so that, secondarily, the full height of column with capital is often a multiple of 6Roman feetwhile the column height itself is a multiple of 5. In its proportions, the Corinthian column is similar to theIonic column,though it is more slender, and stands apart by its distinctive carved capital.[9]

Theabacusupon the capital has concave sides to conform to the outscrolling corners of the capital, and it may have a rosette at the center of each side. Corinthian columns were erected on the top level of the RomanColosseum,holding up the least weight, and also having the slenderest ratio of thickness to height. Their height to width ratio is about 10:1.[9]

One variant is the Tivoli order, found at the Temple of Vesta, Tivoli. The Tivoli order's Corinthian capital has two rows of acanthus leaves and its abacus is decorated with oversizefleuronsin the form of hibiscus flowers with pronounced spiral pistils. The column flutes have flat tops. The frieze exhibits fruitfestoonssuspended betweenbucrania.Above each festoon has arosetteover its center. The cornice does not havemodillions.

Gandharan capitals[edit]

Indo-Corinthian capitalsare capitals crowningcolumnsorpilasters,which can be found in the northwesternIndian subcontinent,and usually combineHellenisticandIndianelements. These capitals are typically dated to the 1st centuries of our era, and constitute important elements ofGreco-Buddhist artofGandhara.

The classical design was often adapted, usually taking a more elongated form, and sometimes being combined with scrolls, generally within the context of Buddhist stupas and temples. Indo-Corinthian capitals also incorporated figures of theBuddhaorBodhisattvas,usually as central figures surrounded, and often in the shade, of the luxurious foliage of Corinthian designs.

Byzantine Empire and Medieval Europe[edit]

Though the term "Corinthian" is reserved for columns and capitals that adhere fairly closely to one of the classical versions, vegetal decoration to capitals continued to be extremely common inByzantine architectureand the various styles of the EuropeanMiddle Ages,fromCarolingian architecturetoRomanesque architectureandGothic architecture.There was considerable freedom in the details and the relationship between column (generally not fluted) and capital. Many types of plant were represented, sometimes realistically, as in the capitals in thechapter houseatSouthwell Minsterin England.

Renaissance Corinthian order[edit]

During the first flush of theItalian Renaissance,the Florentine architectural theoristFrancesco di Giorgioexpressed the human analogies that writers who followed Vitruvius often associated with the human form, in squared drawings he made of the Corinthian capital overlaid with human heads, to show the proportions common to both.[10]

The Corinthianarchitraveis divided in two or three sections, which may be equal, or may bear interesting proportional relationships, to one with another. Above the plain, unadorned architrave lies thefrieze,which may be richly carved with a continuous design or left plain, as at the U.S. Capitol extension. At the Capitol the proportions of architrave to frieze are exactly 1:1. Above that, the profiles of thecornicemouldings are like those of the Ionic order. If the cornice is very deep, it may be supported by brackets or modillions, which are ornamental brackets used in a series under a cornice.

The Corinthian column is almost always fluted, and the flutes of a Corinthian column may be enriched. They may be filleted, with rods nestled within the hollow flutes, or stop-fluted, with the rods rising a third of the way, to where theentasisbegins. In French, these are calledchandellesand sometimes terminate in carved wisps of flame, or with bellflowers. Alternatively, beading or chains of husks may take the place of the fillets in the fluting, Corinthian being the most flexible of the orders, with more opportunities for variation.

Elaborating upon an offhand remark when Vitruvius accounted for the origin of its acanthus capital, it became a commonplace to identify the Corinthian column with the slender figure of a young girl; in this mode the classifying French painterNicolas Poussinwrote to his friendFréart de Chantelouin 1642:

The beautiful girls whom you will have seen inNîmeswill not, I am sure, have delighted your spirit any less than the beautiful columns of Maison Carrée for the one is no more than an old copy of the other.[11]

Sir William Chambersexpressed the conventional comparison with the Doric order:

The proportions of the orders were by the ancients formed on those of the human body, and consequently, it could not be their intention to make a Corinthian column, which, as Vitruvius observes, is to represent the delicacy of a young girl, as thick and much taller than a Doric one, which is designed to represent the bulk and vigour of a muscular full grown man.[12]

History[edit]

The oldest known example of a Corinthian column is in the Temple ofApollo EpicuriusatBassaein Arcadia, c. 450–420 BC. It is not part of the order of the temple itself, which has a Doriccolonnadesurrounding the temple and an Ionic order within thecellaenclosure. A single Corinthian column stands free, centered within the cella. This is a mysterious feature, and archaeologists debate what this shows: some state that it is simply an example of avotive column.A few examples of Corinthian columns in Greece during the next century are all usedinsidetemples. A more famous example, and the first documented use of the Corinthian order on the exterior of a structure, is the circular Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, erected c. 334 BC.

A Corinthian capital carefully buried in antiquity in the foundations of the circulartholosatEpidauruswas recovered during modern archaeological campaigns. Its Enigma tic presence and preservation have been explained as a sculptor's model for stonemasons to follow[13]in erecting the temple dedicated toAsclepius.The architectural design of the building was credited in antiquity to the sculptorPolykleitos the Younger,son of the Classical Greek sculptorPolykleitosthe Elder.

The temple was erected in the 4th century BC. These capitals, in one of the most-visited sacred sites of Greece, influenced later Hellenistic and Roman designs for the Corinthian order. The concave sides of the abacus meet at a sharp keel edge, easily damaged, which in later and post-Renaissance practice has generally been replaced by a canted corner. Behind the scrolls the spreading cylindrical form of the central shaft is plainly visible.

Much later, the Roman writerVitruvius(c. 75 BC– c. 15 BC) related that the Corinthian order had been invented byCallimachus,a Greek architect and sculptor who was inspired by the sight of a votive basket that had been left on the grave of a young girl. A few of her toys were in it, and a square tile had been placed over the basket, to protect them from the weather. Anacanthusplant had grown through the woven basket, mi xing its spiny, deeply cut leaves with the weave of the basket.[14]

Claude Perraultincorporated a vignette epitomizing the Callimachus tale in his illustration of the Corinthian order for his translation of Vitruvius, published in Paris, 1684. Perrault demonstrates in his engraving how the proportions of the carved capital could be adjusted according to demands of the design, without offending. The texture and outline of Perrault's leaves is dry and tight compared to their 19th-century naturalism at the U.S. Capitol.

In Late Antique and Byzantine practice, the leaves may be blown sideways, as if by the wind of Faith. Unlike the Doric and Ionic column capitals, a Corinthian capital has no neck beneath it, just a ring-likeastragalmolding or a banding that forms the base of the capital, recalling the base of the legendary basket.

Most buildings (and most clients) are satisfied with just two orders. When orders are superposed one above another, as they are at theColosseum,the natural progression is from sturdiest and plainest (Doric) at the bottom, to slenderest and richest (Corinthian) at the top. The Colosseum's topmost tier has an unusual order that came to be known as theComposite orderduring the 16th century. The mid-16th-century Italians, especiallySebastiano SerlioandJacopo Barozzi da Vignola,who established acanonicversion of the orders, thought they detected a "Composite order", combining the volutes of the Ionic with the foliage of the Corinthian, but in Roman practice volutes were almost always present.

InRomanesqueandGothic architecture,where the Classical system had been replaced by a new aesthetic composed of arched vaults springing from columns, the Corinthian capital was still retained. It might be severely plain, as in the typicalCistercian architecture,which encouraged no distraction from liturgy and ascetic contemplation, or in other contexts it could be treated to numerous fanciful variations, even on the capitals of a series of columns orcolonetteswithin the same system.

During the 16th century, a sequence of engravings of the orders in architectural treatises helped standardize their details within rigid limits: Sebastiano Serlio; theRegola delli cinque ordiniofGiacomo Barozzi da Vignola(1507–1573);I quattro libri dell'architetturaofAndrea Palladio,and Vincenzo Scamozzi'sL'idea dell'architettura universale,were followed in the 17th century by French treatises with further refined engraved models, such as Perrault's.

Notable examples[edit]

- Argentina

- Bangladesh

- Tajhat Palace,Rangpur

- France

- Maison Carrée,Nimes

- TheJuly Column,Paris

- Germany

- Greece

- Israel

- Italy

- Jordan

- Philippines

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- Serbia

- Singapore

- South Africa

- Syria

- Ukraine

- Great Lavra Belltower(fourth tier – 8 columns)

- Independence Monument

- United Kingdom

- United States of America

Gallery[edit]

-

Reconstructed Corinthian capital, with originalcolours

-

Ancient GreekCorinthian columns in theTemple of Apollo at Bassae,Bassae,Greece, illustration byCharles Robert Cockerell,unknown architect,c.429-400 BC[15]

-

Ancient Greek Corinthian order of theChoragic Monument of Lysicrates,Athens,c.335 BC

-

Ancient Greek Corinthian capital from thetholosatEpidaurus,Archaeological Museum of Epidaurus,Greece, said to have been designed byPolyclitus the Younger,c.350 BC[16]

-

Ancient Greek Corinthian order of theTower of the Winds,Athens, probablyc.50 BC

-

Roman Corinthian capitals in theTemple of Hercules Victor,Rome, later 2nd century BC

-

Roman Corinthian capital of theTemple of Vesta,Tivoli,Italy, with an oversizedfleuron(flower) on theabacus,probably a stylized hibiscus blossom with spiralpistil,compressed acanthus rows, and flutes squared at the top, rather than rounded as on a standard Corinthian column, 1st century BC

-

The variant known as "Tower of the WindsCorinthian "after the monument in Athens,c.50 BC

-

Group ofBuddhaseated between two monks, with two quasi-Corinthian pilasters that are here because of the influence of Greek culture during theHellenistic period,1st-3rd centuries, stone,State Museum of History of Uzbekistan

-

Roman Corinthian capital of theTemple of Castor and Pollux,Rome, with intertwining central stems, 1st century

-

Roman Corinthian columns andpilastersof theArch of Hadrian,Athens, 131 or 132 AD

-

The ConstantinianbasilicaofSanta Sabinainterior, withspoliaCorinthian columns from theTemple of JunoRegina

-

Romanesquequasi-Corinthian columns inSaint-Germain-des-Prés,Paris, 8th century, restored in the 19th century with original polychromy

-

Islamicquasi-Corinthian capital fromAndalusia(Madīnat az-Zahrā’), present-daySpain,mid-10th century, marble, Inv. no. 5053,Pergamon Museum,Berlin

-

Romanesque quasi-Corinthian capital,Church of St. Philibert,Tournus,France,c.1008 to mid-11th century[18]

-

RenaissanceCorinthian pilasters of theBasilica of Sant'Andrea,Mantua,Italy,Leon Battista Alberti,begun inc.1450[19]

-

RenaissanceCorinthian pilasters of the entrance of theSanta Maria dei Miracoli,Venice,byPietro Lombardo,1481–1489

-

Renaissance Corinthian columns of the Tomb ofAscanio Maria Sforza,Santa Maria del Popolo,Rome, byAndrea Sansovino,c.1505

-

BaroqueCorinthian column capitals in theSan Carlo alle Quattro Fontane,Rome, byFrancesco Borromini,1638–1677

-

Baroque Corinthian columns in theChapel of the Palace of Versailles,1696–1710[20]

-

Stylized Baroque Corinthian columns in theAustrian National Library,Hofburg,Vienna,Austria,designed byJohann Bernhard Fischer von Erlachinc.1716–1720, built in 1723–1726[21]

-

BrâncovenescCorinthian capitals of theStavropoleos MonasteryChurch,Bucharest,Romania,unknown architect, 1724

-

Rococoreinterpretations of the Corinthian order in an design for an interior, byFranz Xaver Habermann,1731–1775, etching on paper,Rijksmuseum,Amsterdam,theNetherlands

-

Rococo reinterpretations of the Corinthian order in an altar design, with asymmetric capitals and more sinuous S-shaped acanthuses, by Franz Xaver Habermann, 1740–1745, etching on paper, Rijksmuseum

-

Rococo reinterpretations of the Corinthian order in thePilgrimage Church of Wies,Steingaden,Germany, byDominikusandJohann Baptist Zimmermann,1746-1754[22]

-

Rococo reinterpretations of the Corinthian order at the high altar in theabbey churchofOttobeuren,Germany, byJohann Michael Fischer,1748-1754[23]

-

Neoclassical Corinthian pilaster in the Salon des dames d'honneur,Château de Compiègne,Compiègne,France, unknown architect,c.1810

-

Neoclassical Corinthian capitals of theBirmingham Town Hall,Birmingham,UK,inspired by those of the Temple of Castor and Pollux in Rome, byJoseph HansomandEdward Welch,1834

-

Greek RevivalCorinthian columns of theSturdivant Hall,Selma,Alabama,US, inspired by those of the Tower of the Winds, byThomas Helm Lee,1852–1856

-

The Neoclassical Corinthian order as used in extending theUnited States Capitolin 1854: the column's shaft has been omitted

-

Neoclassical reinterpretation of the Corinthian capital at the Grave ofClaude Bonnefond,Loyasse Cemetery,Lyon,France, designed byAntoine-Marie Chenavardand sculpted byGuillaume Bonnet,c.1860

-

Beaux ArtsCorinthian columns on the facade of thePalais Garnier,Paris, byCharles Garnier,1861–1874[24]

-

Neoclassical Corinthian capital of theTemple de la Sibylle,Parc des Buttes Chaumont,Paris, heavily inspired by those of the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, byGabriel Davioud,1866

-

Greek RevivalCorinthian columns in theAustrian Parliament Building,Vienna,inspired by those of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, byTheophil von Hansen,1873–1883[25]

-

Greek Revival pilaster capitals on the facade of the Austrian Parliament Building

-

Greek Revival Corinthian columns of theBowling Green Offices Building,New York City, a mix of those of the Tower of the Winds and those of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, byW. & G. Audsley,1895-1898[26]

-

Neoclassical polychrome Corinthian columns, entablature and pediment of thePhiladelphia Museum of Art,Philadelphia,US, byHorace TrumbauerandZantzinger, Borie & Medary,1933[27]

-

PostmodernneonCorinthian capital inSouth Bay Galleria,Redondo Beach, California,US, byRTKL AssociatesandTheo Kondos Associates,1985

-

Reinterpreted Postmodern Corinthian columns of theIsle of Dogs Pumping Station,London,John Outram,1988[29]

-

New ClassicalGreek Revival Corinthian column in theGonville and Caius CollegeHall,Cambridge,UK, inspired by the one from the Temple of Apollo at Bassaem byJohn Simpson,1998

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Lawrence, 85; Summerson, 124, 176

- ^ab"Corinthian Columns".Architect of the Capitol.Retrieved2019-03-24.

- ^abSummerson, 124

- ^Lawrence, 179 (Plate 80)

- ^Lawrence, 237

- ^Brown, 232;Fergusson, James,The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture,Vol 2, p. 273, 1855, John Murray,google books

- ^Mark Wilson Jones, "Designing the Roman Corinthian order",Journal of Roman Archaeology2:35-69 (1989).

- ^Jones 1989.

- ^abPeter D'Epiro; Mary Desmond Pinkowish (22 December 2010).What are the Seven Wonders of the World?: And 100 Other Great Cultural Lists--Fully Explicated.Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 133.ISBN978-0-307-49107-7.

- ^Francesco di Giorgio's sheet with the drawings, from the Turin codex Saluzziano of hisTrattati di architettura ingegneria e arte militare,c. 1480–1500, is illustrated byRudolf Wittkower,Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism(1962) 1965, pl. ic

- ^Quoted bySir Kenneth Clark,The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form,1956, p. 45.

- ^Chambers,A Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture(Joseph Gwilt ed, 1825:pp 159–61).

- ^Alison Burford (The Greek Temple Builders at Epidauros,Liverpool, 1969, p. 65) suggests instead that it was spoilt in the carving, one volute being incorrectly detached from its field; Hugh Plommer, reviewing it forThe Classical Review(New Series,21.2 [June 1971], pp 269–272), remarks that the error involved an excess of work and remains convinced that the capital was a model.

- ^Vitr. 4.1.9-10

- ^Watkin, David (2022).A History of Western Architecture.Laurence King. p. 40.ISBN978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^Hugh Honour, John Fleming (2009).A World History of Art - Revised Seventh Edition.Laurence King Publishing. p. 147.ISBN978-1-85669-584-8.

- ^Hugh Honour, John Fleming (2009).A World History of Art - Revised Seventh Edition.Laurence King Publishing. p. 177.ISBN978-1-85669-584-8.

- ^Watkin, David (2022).A History of Western Architecture.Laurence King. p. 123.ISBN978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^Watkin, David (2022).A History of Western Architecture.Laurence King. p. 217.ISBN978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^Martin, Henry (1927).Le Style Louis XIV(in French). Flammarion. p. 39.

- ^Watkin, David (2022).A History of Western Architecture.Laurence King. p. 325.ISBN978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^J. Philippe, Minguet (1973).Estetica Rococoului(in Romanian). Meridiane.

- ^Watkin, David (2022).A History of Western Architecture.Laurence King. p. 333.ISBN978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^Robertson, Hutton (2022).The History of Art - From Prehistory to Presentday - A Global View.Thames & Hudson. p. 989.ISBN978-0-500-02236-8.

- ^Watkin, David (2022).A History of Western Architecture.Laurence King. p. 490.ISBN978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^"Greek Classicism: A Design Resource for Historic and Contemporary Architecture, Part II, with Calder Loth (29:46 in the video)".classicist.org.Retrieved14 June2024.

- ^"Greek Classicism: A Design Resource for Historic and Contemporary Architecture, Part II, with Calder Loth (28:36 in the video)".classicist.org.Retrieved14 June2024.

- ^Hugh Honour, John Fleming (2009).A World History of Art - Revised Seventh Edition.Laurence King Publishing. p. 867.ISBN978-1-85669-584-8.

- ^Gura, Judith (2017).Postmodern Design Complete.Thames & Hudson. p. 121.ISBN978-0-500-51914-1.

References[edit]

- Brown, Frank C.,Study of the Orders,2002 digital edn. (1st edn 1906), Digital Scanning Incorporated, ISBN 9781582187334,google books

- Lawrence, A. W.,Greek Architecture,1957, Penguin, Pelican history of art

- Summerson, John,The Classical Language of Architecture,1980 edition,Thames and HudsonWorld of Artseries,ISBN0500201773

![Ancient Greek Corinthian columns in the Temple of Apollo at Bassae, Bassae, Greece, illustration by Charles Robert Cockerell, unknown architect, c.429-400 BC[15]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Temple_of_Apollo_Epikourios%2C_Bassae%2C_details_of_a_Corinthian_isolated_column_in_the_interior.webp/169px-Temple_of_Apollo_Epikourios%2C_Bassae%2C_details_of_a_Corinthian_isolated_column_in_the_interior.webp.png)

![Ancient Greek Corinthian capital from the tholos at Epidaurus, Archaeological Museum of Epidaurus, Greece, said to have been designed by Polyclitus the Younger, c.350 BC[16]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Corinthian_capital%2C_AM_of_Epidauros%2C_202545.jpg/406px-Corinthian_capital%2C_AM_of_Epidauros%2C_202545.jpg)

![Roman Temple of Olympian Zeus, Athens, 174 BC–c.130 AD[17]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/93/L%27Olympieion_%28Ath%C3%A8nes%29_%2830776483926%29.jpg/405px-L%27Olympieion_%28Ath%C3%A8nes%29_%2830776483926%29.jpg)

![Romanesque quasi-Corinthian capital, Church of St. Philibert, Tournus, France, c.1008 to mid-11th century[18]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ef/Tournus_%2871%29_Abbatiale_Saint-Philibert_-_Int%C3%A9rieur_-_Chapiteau_-_13.jpg/180px-Tournus_%2871%29_Abbatiale_Saint-Philibert_-_Int%C3%A9rieur_-_Chapiteau_-_13.jpg)

![Renaissance Corinthian pilasters of the Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua, Italy, Leon Battista Alberti, begun in c.1450[19]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Fa%C3%A7ade_de_la_basilique_Saint-Andr%C3%A9_de_Mantoue%2C_r%C3%A9alis%C3%A9e_par_Leon_Alberti.jpg/326px-Fa%C3%A7ade_de_la_basilique_Saint-Andr%C3%A9_de_Mantoue%2C_r%C3%A9alis%C3%A9e_par_Leon_Alberti.jpg)

![Baroque Corinthian columns in the Chapel of the Palace of Versailles, 1696–1710[20]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/Versailles_Chapel_-_July_2006_edit.jpg/175px-Versailles_Chapel_-_July_2006_edit.jpg)

![Stylized Baroque Corinthian columns in the Austrian National Library, Hofburg, Vienna, Austria, designed by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach in c.1716–1720, built in 1723–1726[21]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/%C3%96NB_8.jpg/178px-%C3%96NB_8.jpg)

![Rococo reinterpretations of the Corinthian order in the Pilgrimage Church of Wies, Steingaden, Germany, by Dominikus and Johann Baptist Zimmermann, 1746-1754[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/64/Wieskirche%2C_Gemeinde_Steingaden_Ortsteil_Wies.JPG/405px-Wieskirche%2C_Gemeinde_Steingaden_Ortsteil_Wies.JPG)

![Rococo reinterpretations of the Corinthian order at the high altar in the abbey church of Ottobeuren, Germany, by Johann Michael Fischer, 1748-1754[23]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/97/BasilikaOttobeurenHochaltar02.JPG/180px-BasilikaOttobeurenHochaltar02.JPG)

![Beaux Arts Corinthian columns on the facade of the Palais Garnier, Paris, by Charles Garnier, 1861–1874[24]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/Detail_of_the_principal_facade_of_the_Op%C3%A9ra_Garnier%2C_23_March_2010.jpg/405px-Detail_of_the_principal_facade_of_the_Op%C3%A9ra_Garnier%2C_23_March_2010.jpg)

![Greek Revival Corinthian columns in the Austrian Parliament Building, Vienna, inspired by those of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, by Theophil von Hansen, 1873–1883[25]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/2023-04-22_Parlament_S%C3%A4ulenhalle1.jpg/406px-2023-04-22_Parlament_S%C3%A4ulenhalle1.jpg)

![Greek Revival Corinthian columns of the Bowling Green Offices Building, New York City, a mix of those of the Tower of the Winds and those of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, by W. & G. Audsley, 1895-1898[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/Bowling_Green_NYC_Feb_2021_53.jpg/405px-Bowling_Green_NYC_Feb_2021_53.jpg)

![Neoclassical polychrome Corinthian columns, entablature and pediment of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, US, by Horace Trumbauer and Zantzinger, Borie & Medary, 1933[27]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/93/Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art%2C_main_building.jpg/378px-Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art%2C_main_building.jpg)

![Postmodern Corinthian columns of the Piazza d'Italia, New Orleans, US, by Charles Moore, 1978–1979[28]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/PiazzaDItalia1990.jpg/460px-PiazzaDItalia1990.jpg)

![Reinterpreted Postmodern Corinthian columns of the Isle of Dogs Pumping Station, London, John Outram, 1988[29]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Pumping_station%2C_Stewart_Street_%28geograph_4678320%29.jpg/242px-Pumping_station%2C_Stewart_Street_%28geograph_4678320%29.jpg)