Muscogee language

| Muscogee | |

|---|---|

| Creek (exonym) | |

| Mvskoke | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | East centralOklahoma,Muscogee and Seminole, south Alabama Creek,Florida,Seminole of Brighton Reservation. |

| Ethnicity | 100,000Muscogee people(2024)[1] |

Native speakers | fewer than 400 (2024)[2] |

Muskogean

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mus |

| ISO 639-3 | mus |

| Glottolog | cree1270 |

| ELP | Muskogee |

Current geographic distribution of the Creek language | |

Distribution ofNative American languagesinOklahoma | |

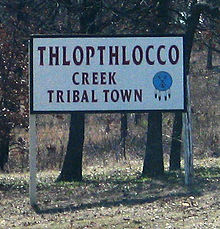

TheMuscogee language(Muskogee,MvskokeIPA:[maskókî]in Muscogee), previously referred to by itsexonym,Creek,[3]is aMuskogean languagespoken byMuscogee(Creek) andSeminolepeople, primarily in theUS statesofOklahomaandFlorida.Along withMikasuki,when it is spoken by the Seminole, it is known asSeminole.

Historically, the language was spoken by various constituent groups of the Muscogee orMaskokiin what are nowAlabamaandGeorgia.It is related to but not mutually intelligible with the other primary language of the Muscogee confederacy,Hitchiti-Mikasuki,which is spoken by the kindred Mikasuki, as well as with other Muskogean languages.

The Muscogee first brought the Muscogee and Miccosukee languages toFloridain the early 18th century. Combining with other ethnicities there, they emerged as theSeminole.During the 1830s, however, the US government forced most Muscogee and Seminole to relocate west of theMississippi River,with most forced intoIndian Territory.

The language is today spoken by fewer than 400 people, most of whom live inOklahomaand are members of theMuscogee Nationand theSeminole Nation of Oklahoma.[4]

Current status

[edit]Muscogee is widely spoken among the Muscogee people. The Muscogee Nation offers free language classes and immersion camps to Muscogee children.[5]

Language programs

[edit]

TheCollege of the Muscogee Nationoffers a language certificate program.[6][7]Tulsapublic schools, theUniversity of Oklahoma[8]and Glenpool Library in Tulsa[9]and the Holdenville,[10]Okmulgee, and Tulsa Muscogee Communities of theMuscogee Nation[11]offer Muscogee Creek language classes. In 2013, theSapulpaCreek Community Center graduated a class of 14 from its Muscogee language class.[12]In 2018, 8 teachers graduated from a class put on by the Seminole nation at Seminole State College to try and reintroduce the Muscogee language to students in elementary and high school in several schools around the state.

Phonology

[edit]The phoneme inventory of Muscogee consists of thirteenconsonantsand threevowel qualities,which distinguishlength,toneandnasalization.[13]It also makes use of thegeminationofstops,fricativesandsonorants.[14]

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Lateral | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Plosive | p | t | tʃ | k | ||

| Fricative | f | s | ɬ | h | ||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||

Plosives

[edit]There are four voiceless stops in Muscogee:/ptt͡ʃk/./t͡ʃ/is avoiceless palatal affricateand patterns as a single consonant and so with the other voiceless stops./t͡ʃ/has analveolarallophone[t͡s]before/k/.[16]Theobstruentconsonants/ptt͡ʃk/are voiced to[bdd͡ʒɡ]betweensonorantsandvowelsbut remain voiceless at the end of asyllable.[17]

Between instances of[o],or after[o]at the end of a syllable, the velar/k/is realized as the uvular[q]or[ɢ].For example:[18]

in-coko 'his or her house' [ɪnd͡ʒʊɢo] tokná:wa 'money' [toqnɑːwə]

Fricatives

[edit]There are four voiceless fricatives in Muscogee:/fsɬh/./f/can be realized as either labiodental[f]or bilabial[ɸ]inplace of articulation.Predominantly among speakers in Florida, the articulation of/s/is morelaminal,resulting in/s/being realized as[ʃ],but for most speakers,/s/is a voiceless apico-alveolar fricative[s].[19]

Like/k/,the glottal/h/is sometimes realized as the uvular [χ] when it is preceded by[o]or when syllable-final:[18]

oh-leyk-itá 'chair' [oχlejɡɪdə] ohɬolopi: 'year' [oχɬolobiː]

Sonorants

[edit]The sonorants in Muscogee are two nasals (/m/and/n/), twosemivowels(/w/and/j/), and the lateral/l/,allvoiced.[20]Nasal assimilation occurs in Muscogee:/n/becomes[ŋ]before/k/.[18]

Sonorants are devoiced when followed by/h/in the same syllable and results in a single voiceless consonant:[21]

camhcá:ka 'bell' [t͡ʃəm̥t͡ʃɑːɡə] akcáwhko 'a type of water bird' [ɑkt͡ʃəw̥ko]

Geminates

[edit]All plosives and fricatives in Muscogee can begeminated(lengthened). Some sonorants may also be geminated, but[hh]and[mm]are less common than other sonorant geminates, especially in roots. For the majority of speakers, except for those influenced by theAlabamaorKoasatilanguages, the geminate[ww]does not occur.[22]

Vowels

[edit]The vowel phonemes of Muscogee are as follows:[15]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | ||

| Close-mid | o oː | ||

| Open | ɑ ɑː |

There are three short vowels/iɑo/and three long vowels/iːɑːoː/.There are also the nasal vowels/ĩɑ̃õĩːɑ̃ːõː/(in the linguistic orthography, they are often written with anogonekunder them or a following superscript "n" ). Most occurrences of nasal vowels are the result of nasal assimilation or the nasalizing grade, but there are some forms that show contrast between oral and nasal vowels:[23]

pó-ɬki 'our father' opónɬko 'cutworm'

Short vowels

[edit]The three short vowels/iɑo/can be realized as the lax and centralized ([ɪəʊ]) when a neighboring consonant iscoronalor in closed syllables. However,/ɑ/will generally not centralize when it is followed by/h/or/k/in the same syllable, and/o/will generally remain noncentral if it is word-final.[22]Initial vowels can be deleted in Muscogee, mostly applying to the vowel/i/.The deletion will affect the pitch of the following syllable by creating a higher-than-expected pitch on the new initial syllable. Furthermore, initial vowel deletion in the case of single-morpheme, short words such asifa'dog' oricó'deer' is impossible, as the shortest a Muscogee word can be is a one-syllable word ending in a long vowel (fóː'bee') or a two-syllable word ending with a short vowel (ací'corn').[24]

Long vowels

[edit]There are three long vowels in Muscogee (/iːɑːoː/), which are slightly longer than short vowels and are never centralized.

Long vowels are rarely followed by a sonorant in the same syllable. Therefore, when syllables are created (often from suffixation or contractions) in which a long vowel is followed by a sonorant, the vowel is shortened:[25]

in-ɬa:m-itá 'to uncover, open' in-ɬam-k-itá 'to be uncovered, open'

Diphthongs

[edit]In Muscogee, there are three diphthongs, generally realized as[əɪʊjəʊ].[26]

Nasal vowels

[edit]Both long and short vowels can be nasalized (the distinction betweenaccesandąccesbelow), but long nasal vowels are more common. Nasal vowels usually appear as a result of a contraction, as the result of a neighboring nasal consonant, or as the result of nasalizing grade, a grammaticalablaut,which indicates intensification through lengthening and nasalization of a vowel (likoth-'warm' with the nasalizing grade intensifies the word tolikŏ:nth-os-i:'nice and warm').[27]Nasal vowels may also appear as part of a suffix that indicates a question (o:sk-ihá:n'I wonder if it's raining').[23]

Tones

[edit]There are three phonemic tones in Muscogee; they are generally unmarked except in the linguistic orthography: high (marked in the linguistic orthography with anacute accent:á,etc.), low (unmarked:a,etc.), and falling (marked with acircumflex:â,etc.).

Orthography

[edit]The traditional MuscogeeAlpha betwas adopted by the tribe in the late 1800s[28]and has 20letters.

Although it is based on theLatin Alpha bet,some sounds are vastly different from those inEnglishlike those represented byc,e,i,r,andv.Here are the (approximately) equivalent sounds using familiar English words and theIPA:

| Spelling | Sound (IPA) | English equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| a | aː~a | like the "a" in father |

| c | tʃ~ts | like the "ch" in suchor the "ts" in cats |

| e | ɪ | like the "i" in hit |

| ē | iː | like the "ee" in seed |

| f | f | like the "f" infather |

| h | h | like the "h" inhatch |

| i | ɛ~ɛj | like the "ay" in day |

| k | k | like the "k" in skim |

| l | l | like the "l" inlook |

| m | m | like the "m" inmoon |

| n | n | like the "n" in moon |

| o | oː~ʊ~o | like the "o" in bone or the "oo" in book |

| p | p | like the "p" in spot |

| r | ɬ | a soundthat does not occur in English but is often represented as "hl" or "thl" in non-Muscogee texts. The sound is made by blowing air around the sides of the tongue while pronouncing Englishland is identical toWelshll. |

| s | s | like the "s" inspot |

| t | t | like the "t" in stop |

| u | ʊ~o | like the "oo" in book or the "oa" in boat |

| v | ə~a | like the "a" inabout |

| w | w | like the "w" inwet |

| y | j | like the "y" inyet |

There are also three vowel sequences whose spellings match their phonetic makeup:[29]

| Spelling | Sound (IPA) | English equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| eu | iʊ | similar to the exclamation "ew!". A combination of the sounds represented byeandu |

| ue | oɪ | like the "oy" in boy |

| vo | aʊ~əʊ | like the "ow" in how |

Consonants

[edit]As mentioned above, certain consonants in Muscogee, when they appear between twosonorants(a vowel orm,n,l,w,ory), becomevoiced.[28]They are the consonants represented byp,t,k,c,ands:

- ccan sound like[dʒ],the "j" injust

- kcan sound like[ɡ],the "g" ingoat

- pcan sound like[b],the "b" inboat

- scan sound like[z],the "z" inzoo

- tcan sound like[d],the "d" indust

In addition, certain combinations of consonants sound differently from English, giving multiple possibletranscriptions.The most prominent case is the second person singular ending for verbs.Wiketvmeans "to stop:" the verb for "you are stopping" may be written in Muscogee aswikeckesorwiketskes.Both are pronounced the same. The-eck-transliteration is preferred by Innes (2004), and the-etsk-transliteration has been used by Martin (2000) and Loughridge (1964).

Vowel length

[edit]While vowel length in Muscogee is distinctive, it is somewhat inconsistently indicated in the traditional orthography. The following basic correspondences can be noted:

- The short vowelvwith the long vowela(/a/vs./aː/)

- The short vowelewith the long vowelē(/i/vs./iː/)

- The short voweluwith the long vowelo(/o/vs./oː/)

However, the correspondences do not always apply,[30]and in some words, short/a/is spelleda,long/iː/is spellede,and short/o/is spelledo.

Nonstandard orthography

[edit]Muscogee words carry distinctivetonesandnasalizationof their vowels. These features are not marked in the traditional orthography, only in dictionaries and linguistic publications. The following additional markers have been used by Martin (2000) and Innes (2004):

- Falling tonein a syllable is shown using acircumflex.In English, falling tone is found in phrases such as "uh-oh" or commands such as "stop!" In Muscogee, however, changing a verb such asacces( "she is putting on (a dress)" ) toâccesalters the meaning from one of process to one of state ( "she is wearing (a dress)" ).

- Nasalizationof a vowel is shown with anogonekunder the vowel. Changing the verbaccestoąccesadds theimperfective aspect,a sense of repeated or habitual action ( "she kept putting on (that same dress)" ).

- Thekey syllableof a word is often shown with an accent and is the last syllable that has normal (high) tone within a word; the following syllables are all lower in pitch.

Grammar

[edit]Word order

[edit]The generalsentencestructure fits the patternsubject–object–verb.The subject or object may be anounor a noun followed by one or moreadjectives.Adverbstend to occur either at the beginning of the sentence (for time adverbs) or immediately before the verb (for manner adverbs).

Grammatical case

[edit]Case is marked on noun phrases using the clitics-tfor subjects, and-nfor non-subjects. The clitic-ncan appear on multiple noun phrases in a single sentence at once, such as the direct object, indirect object, and adverbial nouns. Despite the distinction in verbal affixes between theagentandpatientof the verb, the clitic-tmarks subject of both transitive and intransitive verbs.

In some situations, case marking is omitted. This is especially true of sentences with only one noun where the role of the noun is obvious from the personal marking on the verb. Case marking is also omitted on fixed phrases that use a noun, e.g. "goto town"or" builda fire".

Verbs

[edit]In Muscogee, a single verb can translate into an entire English sentence. The rootinfinitiveform of the verb is altered for:

- Person of agent.Letketv= to run.

- Lētkis.= I am running.

- Lētketskes.= You are running.

- Lētkes.= He / She is running.

- Plural forms can be a bit more complicated (see below).

- Person of patient and/or indirect object.That is accomplished withprefixes.Hecetv= to see.

- Cehēcis= I see you.

- Cvhēcetskes.= You see me.

- Hvtvm Cehēcares.= I will see you again.

- Tense.Pohetv= to hear.

- Pohis.= I am hearing (present).

- Pohhis.= I just heard (first or immediate past; within a day ago).

- Pohvhanis.= I am going to hear.

- Pohares.= I will hear.

- Pohiyvnks.= I heard recently (second or middle past, within a week ago).

- Pohimvts.= I heard (third or distant past, within a year ago).

- Pohicatēs.= Long ago I heard (fourth or remote past, beyond a year ago).

- There are at least ten more tenses, includingperfectversions of the above, as well as future, indefinite, andpluperfect.

- Mood.Wiketv= to stop.

- Wikes.= He / She is stopping (indicative).

- Wikvs.= Stop! (imperative)

- Wike wites.= He / She may stop (potential).

- Wiken omat.= If he / she stops (subjunctive).

- Wikepices.= He / She made someone stop (causative).

- Aspect.Kerretv= to learn.

- Kērris.= I am learning (progressive, ongoing or in progress).

- Kêrris.= I know (resulting state).

- Kęrris.= I keep learning (imperfect, habitual or repeated action).

- Kerîyis.= I just learned (action completed in the past).

- Voice.

- Wihkis.= I just stopped (active voice, 1st past).

- Cvwihokes.= I was just stopped (passive voice, 1st past).

- Negatives.

- Wikarēs.= I will stop (positive, future tense).

- Wikakarēs.= I will not stop (negative, future tense).

- Questions.Hompetv= to eat;nake= what.

- Hompetskes.= You are eating.

- Hompetskv?= Are you eating? (expecting a yes or no answer)

- Naken hompetska?= What are you eating? (expecting a long answer)

Verbs with irregular plurals

[edit]Some Muscogee verbs, especially those involving motion, have highly irregular plurals:letketv= to run, with a singular subject, buttokorketv= to run of two subjects andpefatketv= to run of three or more.

Stative verbs

[edit]Another entire class of Muscogee verbs is thestative verbs,which express no action, imply no duration, and provide only description of a static condition. In some languages, such as English, they are expressed as adjectives. In Muscogee, the verbs behave like adjectives but are classed and treated as verbs. However, they are not altered for the person of the subject by anaffix,as above; instead, theprefixchanges:

- enokkē= to be sick;

- enokkēs= he / she is sick;

- cvnokkēs= I'm sick;

- cenokkēs= you are sick.

Locative prefixes

[edit]Prefixes are also used in Muscogee for shades of meaning of verbs that are expressed, in English, by adverbs inphrasal verbs.For example, in English, the verbto gocan be changed toto go up,to go in,to go around,and other variations. In Muscogee, the same principle of shading a verb's meaning is handled by locative prefixes:

Example:

- vyetv= to go (singular subjects only, see above);

- ayis= I am going;

- ak-ayis= I am going (in water / in a low place / under something);

- tak-ayis= I am going (on the ground);

- oh-ayis= I am going (on top of something).

However, for verbs of motion, Muscogee has a large selection of verbs with a specific meaning:ossetv= to go out;ropottetv= to go through.

Switch-reference

[edit]Clauses in a sentence useswitch-referenceclitics to co-ordinate their subjects. The clitic-ton a verb in a clause marks that the verb's subject is the same as that of the next clause. The clitic-nmarks that verb's subject is different from the next clause.

Possession

[edit]In some languages, a special form of the noun, thegenitive case,is used to showpossession.In Muscogee this relationship is expressed in two quite different ways, depending on the nature of the noun.

Nouns in fixed relationships (inalienable possession)

[edit]A body part or family member cannot be named in Muscogee without mentioning the possessor, which is an integrated part of the word. A set of changeable prefixes serves this function:

- enke= his / her hand

- cvnke= my hand

- cenke= your hand

- punke= our hand

Even if the possessor is mentioned specifically, the prefix still must be part of the word:Toskē enke= Toske's hand. It is not redundant in Muscogee ( "Toske his_hand" ).

Transferable nouns

[edit]All other nouns are possessed through a separate set ofpronouns.

- efv= dog;

- vm efv= my dog;

- cem efv= your dog;

- em efv= his / her dog;

- pum efv= our dog.

Again, even though the construction in English would be redundant, the proper way to form the possessive in Muscogee must include the correct preposition:Toskē em efv= Toske's dog. That is grammatically correct in Muscogee, unlike the literal English translation "Toske his dog".

Locative nouns

[edit]A final distinctive feature, related to the above, is the existence oflocational nouns.In English, speakers have prepositions to indicate location, for example,behind,around,beside,and so on. In Muscogee, the locations are actually nouns. These are possessed just like parts of the body and family members were above.

- cuko= house;yopv= noun for "behind";cuko yopv= behind the house;cvyopv= behind me;ceyopv= behind you.

- lecv= under;eto= tree;eto lecv= under the tree.

- tempe= near;cvtempe= near me;cetempe= near you;putempe= near us.

Examples

[edit]- Family.

- Erke.= Father.

- Ecke.= Mother.

- Pauwv.= Maternal Uncle.

- Erkuce.= Paternal Uncle.

- Eckuce.= Aunt.

- Puca.= Grandpa.

- Puse.= Grandma.

- Cēpvnē.= Boy.

- Hoktuce.= Girl.

Male vs. female speech

[edit]Claudio Saunt,writing about the language of the later 18th century, said that there were different feminine and masculine versions, which he also calls dialects, of the Muscogee language. Males "attach[ed] distinct endings to verbs", while Females "accent[ed] different syllables". These forms, mentioned in the first (1860) grammar of the Muscogee language, persisted in theHichiti,Muscogee proper, andKoasatilanguages at least into the first half of the 20th century.[31]: 141

Seminole dialects

[edit]The forms of Muscogee used by theSeminolesof Oklahoma and Florida are separate dialects from the ones spoken by Muscogee people. Oklahoma Seminole speak a dialect known as Oklahoma Seminole Creek. Florida Seminole Creek is one of two languages spoken among Florida Seminoles; it is less common than the Mikasuki language. The most distinct dialect of the language is said to be that of the Florida Seminole, which is described as "rapid", "staccato" and "dental", with more loan words from Spanish and Mikasuki as opposed to English. Florida Seminole Creek is the most endangered register of the Muscogee language.[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^Muscogee Nation website

- ^Powell, Amy; Martin, Jack (May 17, 2024). "The Muscogee Language Documentation Project". William & Mary.

- ^"Muscogee Citizen Data".Muscogee Nation.

- ^Powell, Amy; Martin, Jack (May 17, 2024). "The Muscogee Language Documentation Project". William & Mary

- ^"Muscogee (Creek) Nation".Archived fromthe originalon 2015-07-15.Retrieved2015-07-15.

- ^"Academics."College of the Muscogee Nation.(retrieved 27 Dec 2010)

- ^Pratt, Stacey (2013-04-15)."Language vital part of cultural identity".Tahlequah Daily Press.Retrieved2013-04-17.

- ^"Creek,"Archived2011-02-24 at theWayback MachineUniversity of Oklahoma: The Department of Anthropology.(retrieved 27 Dec 2010)

- ^"Library Presents Mvskoke (Creek) Language Class."Native American Times.8 Sept 2009 (retrieved 27 Dec 2010)

- ^"Holdenville Indian Community."Muscogee (Creek) Nation.(retrieved 27 Dec 2010)

- ^"Thunder Road Theater Company to perform plays in the Mvskoke (Creek) Language."Archived2015-07-15 at theWayback MachineMuscogee (Creek) Nation.(retrieved 27 Dec 2010)

- ^Brock, John (2013-08-17)."Creek language class graduates 14".Sapulpa Herald Online.Sapulpa, Oklahoma.Archived fromthe originalon 2013-08-23.Retrieved2013-08-23.

- ^Hardy 2005:211-12

- ^Martin, 2011, p. 50–51

- ^abMartin, 2011, p. 47

- ^Martin, 2011, p.48-49

- ^Martin, 2011, p. 62

- ^abcMartin, 2011, p. 63

- ^Martin, 2011, p. 49

- ^Martin, 2011, p.49-50

- ^Martin, 2011, p.64

- ^abMartin, 2011, p. 51

- ^abMartin, 2011, p. 53

- ^Martin, 2011, pp. 64, 72-23

- ^Martin, 2011, p. 64–65

- ^Martin, 2011, pp. 54–55

- ^Martin, 2011, pp. 53–54, 95

- ^abInnes 2004

- ^Hardy 2005, pg. 202

- ^Hardy 2005, pp. 201-2

- ^Saunt, Claudio (1999).A New Order of Things. Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1810.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0521660432.

- ^Brown, Keith, and Sarah Ogilvie (2008).Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world,pp. 738–740. Elsevier. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Haas, Mary R.and James H. Hill. 2014. Creek (Muskogee) Texts.[2]Edited and translated by Jack B. Martin, Margaret McKane Mauldin, and Juanita McGirt. UC Publications in Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hardy, Donald E. (January 2005). "Creek". In Hardy, Heather K.; Scancarelli, Janine (eds.).Native Languages of the Southeastern United States.Lincoln, NE:University of Nebraska Press(published 2005). pp. 200–245.ISBN0803242352.

- Johnson, Keith; Martin, Jack (2001)."Acoustic Vowel Reduction in Creek: Effects of Distinctive Length and Position in the Word"(PDF).Phonetica.58(1–2): 81–102.doi:10.1159/000028489.PMID11096370.S2CID38872292.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2010-06-26.Retrieved2009-04-26.

- Innes, Pamela; Linda Alexander; Bertha Tilkens (2004).Beginning Creek: Mvskoke Emponvkv.Norman, OK:University of Oklahoma Press.ISBN0-8061-3583-2.

- Loughridge, R.M.; David M. Hodge (1964).Dictionary Muskogee and English.Okmulgee, OK: Baptist Home Mission Board.

- Martin, Jack B. (2011).A Grammar of Creek (Muskogee).Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.ISBN9780803211063.

- Martin, Jack B.; Margaret McKane Maudlin (2000).A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee.Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.ISBN0-8032-8302-4.

External links

[edit]- TheCreek Language Archive.This site includes a draft of a Creek textbook, which may bedownloadedin.pdf format (Pum Opunvkv, Pun Yvhiketv, Pun Fulletv: Our Language, Our Songs, Our Waysby Margaret Mauldin, Jack Martin, and Gloria McCarty).

- The official website for theMuskogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma

- Acoustic vowel reduction in Creek: Effects of distinctive length and position in the word(pdf)

- Mvskoke Nakcokv Eskerretv Esvhokkolat. Creek Second Reader. (1871)

- Muskogee Genesis Translation

- OLAC resources in and about the Creek language

- ^Powell, Amy; Martin, Jack (May 17, 2024)."The Muscogee Language Documentation Project".William & Mary.

- ^"Haas/Hill texts - Muskogee (Seminole/Creek) Documentation Project".Muskogee (Seminole/Creek) Documentation Project.Retrieved2017-12-22.