Cyanobacteria

| Cyanobacteria Temporal range:(Possible Paleoarchean records)

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Microscope image ofCylindrospermum,a filamentous genus of cyanobacteria | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Clade: | Terrabacteria |

| Clade: | Cyanobacteria-Melainabacteria group |

| Phylum: | Cyanobacteria Stanier,1973 |

| Class: | Cyanophyceae |

| Orders[3] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Cyanobacteria(/saɪˌænoʊbækˈtɪəri.ə/), also calledCyanobacteriotaorCyanophyta,are aphylumofautotrophicgram-negative bacteria[4]that can obtainbiological energyviaoxygenic photosynthesis.The name "cyanobacteria" (fromAncient Greekκύανος(kúanos)'blue') refers to their bluish green (cyan) color,[5][6]which forms the basis of cyanobacteria's informalcommon name,blue-green algae,[7][8][9]although asprokaryotesthey are not scientifically classified asalgae.[note 1]

Cyanobacteria are probably the most numeroustaxonto have ever existed on Earth and the first organisms known to have producedoxygen,[10]having appeared in the middleArchean eonand apparently originated in afreshwaterorterrestrial environment.[11]Theirphotopigmentscan absorb the red- and blue-spectrum frequencies ofsunlight(thus reflecting a greenish color) to splitwater moleculesintohydrogen ionsand oxygen. The hydrogen ions are used to react withcarbon dioxideto produce complexorganic compoundssuch ascarbohydrates(a process known ascarbon fixation), and the oxygen is released as abyproduct.By continuously producing and releasing oxygen over billions of years, cyanobacteria are thought to have converted theearly Earth's anoxic,weakly reducingprebiotic atmosphereinto anoxidizingone with free gaseous oxygen (which would have been immediately removed by varioussurfacereductantspreviously), resulting in theGreat Oxidation Eventand the "rusting of the Earth"during the earlyProterozoic,[12]dramatically changing the composition of life forms on Earth.[13]The subsequentadaptationof earlysingle-celled organismsto survive in oxygenous environments likely had led toendosymbiosisbetweenanaerobesandaerobes,and hence the evolution ofeukaryotesduring thePaleoproterozoic.

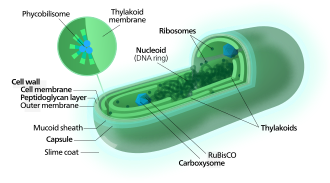

Cyanobacteria usephotosynthetic pigmentssuch as various forms ofchlorophyll,carotenoids,phycobilinsto convert thephotonic energyin sunlight tochemical energy.Unlikeheterotrophicprokaryotes, cyanobacteria haveinternal membranes.These are flattened sacs calledthylakoidswhere photosynthesis is performed.[14][15]Photoautotrophiceukaryotes such asred algae,green algaeandplantsperform photosynthesis in chlorophyllicorganellesthat are thought to have their ancestry in cyanobacteria, acquired long ago via endosymbiosis. Theseendosymbiontcyanobacteria in eukaryotes then evolved and differentiated into specialized organelles such aschloroplasts,chromoplasts,etioplasts,andleucoplasts,collectively known asplastids.

Sericytochromatia, the proposed name of theparaphyleticand most basal group, is the ancestor of both the non-photosynthetic groupMelainabacteriaand the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, also called Oxyphotobacteria.[16]

The cyanobacteriaSynechocystisandCyanotheceare important model organisms with potential applications in biotechnology forbioethanolproduction, food colorings, as a source of human and animal food, dietary supplements and raw materials.[17]Cyanobacteria produce a range of toxins known ascyanotoxinsthat can cause harmful health effects in humans and animals.

Overview

[edit]

Cyanobacteria are a very large and diverse phylum ofphotosyntheticprokaryotes.[19]They are defined by their unique combination ofpigmentsand their ability to performoxygenic photosynthesis.They often live incolonial aggregatesthat can take on a multitude of forms.[20]Of particular interest are thefilamentous species,which often dominate the upper layers ofmicrobial matsfound in extreme environments such ashot springs,hypersaline water,deserts and the polar regions,[21]but are also widely distributed in more mundane environments as well.[22]They are evolutionarily optimized for environmental conditions of low oxygen.[23]Some species arenitrogen-fi xingand live in a wide variety of moist soils and water, either freely or in a symbiotic relationship with plants orlichen-formingfungi(as in the lichen genusPeltigera).[24]

Cyanobacteria are globally widespread photosynthetic prokaryotes and are major contributors to globalbiogeochemical cycles.[25]They are the only oxygenic photosynthetic prokaryotes, and prosper in diverse and extreme habitats.[26]They are among the oldest organisms on Earth with fossil records dating back at least 2.1 billion years.[27]Since then, cyanobacteria have been essential players in the Earth's ecosystems. Planktonic cyanobacteria are a fundamental component ofmarine food websand are major contributors to globalcarbonandnitrogen fluxes.[28][29]Some cyanobacteria formharmful algal bloomscausing the disruption of aquatic ecosystem services and intoxication of wildlife and humans by the production of powerful toxins (cyanotoxins) such asmicrocystins,saxitoxin,andcylindrospermopsin.[30][31]Nowadays, cyanobacterial blooms pose a serious threat to aquatic environments and public health, and are increasing in frequency and magnitude globally.[32][25]

Cyanobacteria are ubiquitous in marine environments and play important roles asprimary producers.They are part of the marinephytoplankton,which currently contributes almost half of the Earth's total primary production.[33]About 25% of the global marine primary production is contributed by cyanobacteria.[34]

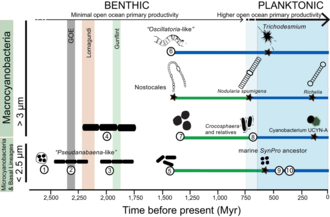

Within the cyanobacteria, only a few lineages colonized the open ocean:Crocosphaeraand relatives,cyanobacterium UCYN-A,Trichodesmium,as well asProchlorococcusandSynechococcus.[35][36][37][38]From these lineages, nitrogen-fi xing cyanobacteria are particularly important because they exert a control onprimary productivityand theexport of organic carbonto the deep ocean,[35]by converting nitrogen gas into ammonium, which is later used to make amino acids and proteins. Marinepicocyanobacteria(ProchlorococcusandSynechococcus) numerically dominate most phytoplankton assemblages in modern oceans, contributing importantly to primary productivity.[37][38][39]While some planktonic cyanobacteria are unicellular and free living cells (e.g.,Crocosphaera,Prochlorococcus,Synechococcus); others have established symbiotic relationships withhaptophyte algae,such ascoccolithophores.[36]Amongst the filamentous forms,Trichodesmiumare free-living and form aggregates. However, filamentous heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria (e.g.,Richelia,Calothrix) are found in association withdiatomssuch asHemiaulus,RhizosoleniaandChaetoceros.[40][41][42][43]

Marine cyanobacteria include the smallest known photosynthetic organisms. The smallest of all,Prochlorococcus,is just 0.5 to 0.8 micrometres across.[44]In terms of numbers of individuals,Prochlorococcusis possibly the most plentiful genus on Earth: a single millilitre of surface seawater can contain 100,000 cells of this genus or more. Worldwide there are estimated to be severaloctillion(1027,a billion billion billion) individuals.[45]Prochlorococcusis ubiquitous between latitudes 40°N and 40°S, and dominates in theoligotrophic(nutrient-poor) regions of the oceans.[46]The bacterium accounts for about 20% of the oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere.[47]

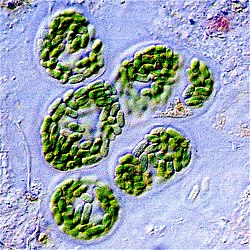

Morphology

[edit]Cyanobacteria are variable in morphology, ranging fromunicellularandfilamentoustocolonial forms.Filamentous forms exhibit functional cell differentiation such asheterocysts(for nitrogen fixation),akinetes(resting stage cells), andhormogonia(reproductive, motile filaments). These, together with the intercellular connections they possess, are considered the first signs of multicellularity.[48][49][50][25]

Many cyanobacteria form motile filaments of cells, calledhormogonia,that travel away from the main biomass to bud and form new colonies elsewhere.[51][52]The cells in a hormogonium are often thinner than in the vegetative state, and the cells on either end of the motile chain may be tapered. To break away from the parent colony, a hormogonium often must tear apart a weaker cell in a filament, called a necridium.

scale bars about 10 μm

• Non-heterocytous:(c)Arthrospira maxima,

Some filamentous species can differentiate into several differentcelltypes:

- Vegetative cells – the normal, photosynthetic cells that are formed under favorable growing conditions

- Akinetes– climate-resistant spores that may form when environmental conditions become harsh

- Thick-walledheterocysts– which contain the enzymenitrogenasevital fornitrogen fixation[54][55][56]in an anaerobic environment due to its sensitivity to oxygen.[56]

Each individual cell (each single cyanobacterium) typically has a thick, gelatinouscell wall.[57]They lackflagella,but hormogonia of some species can move about byglidingalong surfaces.[58]Many of the multicellular filamentous forms ofOscillatoriaare capable of a waving motion; the filament oscillates back and forth. In water columns, some cyanobacteria float by forminggas vesicles,as inarchaea.[59]These vesicles are notorganellesas such. They are not bounded bylipid membranes,but by a protein sheath.

Nitrogen fixation

[edit]

Some cyanobacteria can fix atmosphericnitrogenin anaerobic conditions by means of specialized cells calledheterocysts.[55][56]Heterocysts may also form under the appropriate environmental conditions (anoxic) when fixed nitrogen is scarce. Heterocyst-forming species are specialized for nitrogen fixation and are able to fix nitrogen gas intoammonia(NH3),nitrites(NO−2) ornitrates(NO−3), which can be absorbed by plants and converted to protein and nucleic acids (atmospheric nitrogen is notbioavailableto plants, except for those having endosymbioticnitrogen-fi xing bacteria,especially the familyFabaceae,among others).

Free-living cyanobacteria are present in the water ofrice paddies,and cyanobacteria can be found growing asepiphyteson the surfaces of the green alga,Chara,where they may fix nitrogen.[60]Cyanobacteria such asAnabaena(a symbiont of the aquatic fernAzolla) can provide rice plantations withbiofertilizer.[61]

Photosynthesis

[edit]

Carbon fixation

[edit]Cyanobacteria use the energy ofsunlightto drivephotosynthesis,a process where the energy of light is used to synthesizeorganic compoundsfrom carbon dioxide. Because they are aquatic organisms, they typically employ several strategies which are collectively known as a "CO2concentrating mechanism "to aid in the acquisition of inorganic carbon (CO2orbicarbonate). Among the more specific strategies is the widespread prevalence of the bacterial microcompartments known ascarboxysomes,[63]which co-operate with active transporters of CO2and bicarbonate, in order to accumulate bicarbonate into the cytoplasm of the cell.[64]Carboxysomes areicosahedralstructures composed of hexameric shell proteins that assemble into cage-like structures that can be several hundreds of nanometres in diameter. It is believed that these structures tether the CO2-fi xing enzyme,RuBisCO,to the interior of the shell, as well as the enzymecarbonic anhydrase,usingmetabolic channelingto enhance the local CO2concentrations and thus increase the efficiency of the RuBisCO enzyme.[65]

Electron transport

[edit]In contrast topurple bacteriaand other bacteria performinganoxygenic photosynthesis,thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria are not continuous with the plasma membrane but are separate compartments.[66]The photosynthetic machinery is embedded in thethylakoidmembranes, withphycobilisomesacting aslight-harvesting antennaeattached to the membrane, giving the green pigmentation observed (with wavelengths from 450 nm to 660 nm) in most cyanobacteria.[67]

While most of the high-energyelectronsderived from water are used by the cyanobacterial cells for their own needs, a fraction of these electrons may be donated to the external environment viaelectrogenicactivity.[68]

Respiration

[edit]Respirationin cyanobacteria can occur in the thylakoid membrane alongside photosynthesis,[69]with their photosyntheticelectron transportsharing the same compartment as the components of respiratory electron transport. While the goal of photosynthesis is to store energy by building carbohydrates from CO2,respiration is the reverse of this, with carbohydrates turned back into CO2accompanying energy release.

Cyanobacteria appear to separate these two processes with their plasma membrane containing only components of the respiratory chain, while the thylakoid membrane hosts an interlinked respiratory and photosynthetic electron transport chain.[69]Cyanobacteria use electrons fromsuccinate dehydrogenaserather than fromNADPHfor respiration.[69]

Cyanobacteria only respire during the night (or in the dark) because the facilities used for electron transport are used in reverse for photosynthesis while in the light.[70]

Electron transport chain

[edit]Many cyanobacteria are able to reduce nitrogen and carbon dioxide underaerobicconditions, a fact that may be responsible for their evolutionary and ecological success. The water-oxidizing photosynthesis is accomplished by coupling the activity ofphotosystem(PS) II and I (Z-scheme). In contrast togreen sulfur bacteriawhich only use one photosystem, the use of water as an electron donor is energetically demanding, requiring two photosystems.[71]

Attached to the thylakoid membrane,phycobilisomesact aslight-harvesting antennaefor the photosystems.[72]The phycobilisome components (phycobiliproteins) are responsible for the blue-green pigmentation of most cyanobacteria.[73]The variations on this theme are due mainly tocarotenoidsandphycoerythrinsthat give the cells their red-brownish coloration. In some cyanobacteria, the color of light influences the composition of the phycobilisomes.[74][75]In green light, the cells accumulate more phycoerythrin, which absorbs green light, whereas in red light they produce morephycocyaninwhich absorbs red. Thus, these bacteria can change from brick-red to bright blue-green depending on whether they are exposed to green light or to red light.[76]This process of "complementary chromatic adaptation" is a way for the cells to maximize the use of available light for photosynthesis.

A few genera lack phycobilisomes and havechlorophyll binstead (Prochloron,Prochlorococcus,Prochlorothrix). These were originally grouped together as theprochlorophytesor chloroxybacteria, but appear to have developed in several different lines of cyanobacteria. For this reason, they are now considered as part of the cyanobacterial group.[77][78]

Metabolism

[edit]In general, photosynthesis in cyanobacteria uses water as anelectron donorand producesoxygenas a byproduct, though some may also usehydrogen sulfide[79]a process which occurs among other photosynthetic bacteria such as thepurple sulfur bacteria.

Carbon dioxideis reduced to formcarbohydratesvia theCalvin cycle.[80]The large amounts of oxygen in the atmosphere are considered to have been first created by the activities of ancient cyanobacteria.[81]They are often found assymbiontswith a number of other groups of organisms such as fungi (lichens),corals,pteridophytes(Azolla),angiosperms(Gunnera), etc.[82]The carbon metabolism of cyanobacteria include the incompleteKrebs cycle,[83]thepentose phosphate pathway,andglycolysis.[84]

There are some groups capable ofheterotrophicgrowth,[85]while others areparasitic,causing diseases in invertebrates or algae (e.g., theblack band disease).[86][87][88]

Ecology

[edit]

Cyanobacteria can be found in almost every terrestrial andaquatic habitat–oceans,fresh water,damp soil, temporarily moistened rocks indeserts,bare rock and soil, and evenAntarcticrocks. They can occur asplanktoniccells or formphototrophic biofilms.They are found inside stones and shells (inendolithic ecosystems).[90]A few areendosymbiontsinlichens,plants, variousprotists,orspongesand provide energy for thehost.Some live in the fur ofsloths,providing a form ofcamouflage.[91]

Aquatic cyanobacteria are known for their extensive and highly visiblebloomsthat can form in bothfreshwaterand marine environments. The blooms can have the appearance of blue-green paint or scum. These blooms can betoxic,and frequently lead to the closure of recreational waters when spotted.Marine bacteriophagesare significantparasitesof unicellular marine cyanobacteria.[92]

Cyanobacterial growth is favoured in ponds and lakes where waters are calm and have little turbulent mi xing.[93]Their lifecycles are disrupted when the water naturally or artificially mixes from churning currents caused by the flowing water of streams or the churning water of fountains. For this reason blooms of cyanobacteria seldom occur in rivers unless the water is flowing slowly. Growth is also favoured at higher temperatures which enableMicrocystisspecies to outcompetediatomsandgreen algae,and potentially allow development of toxins.[93]

Based on environmental trends, models and observations suggest cyanobacteria will likely increase their dominance in aquatic environments. This can lead to serious consequences, particularly the contamination of sources ofdrinking water.Researchers includingLinda LawtonatRobert Gordon University,have developed techniques to study these.[94]Cyanobacteria can interfere withwater treatmentin various ways, primarily by plugging filters (often large beds of sand and similar media) and by producingcyanotoxins,which have the potential to cause serious illness if consumed. Consequences may also lie within fisheries and waste management practices. Anthropogeniceutrophication,rising temperatures, vertical stratification and increasedatmospheric carbon dioxideare contributors to cyanobacteria increasing dominance of aquatic ecosystems.[95]

Cyanobacteria have been found to play an important role in terrestrial habitats and organism communities. It has been widely reported that cyanobacteriasoil crustshelp to stabilize soil to preventerosionand retain water.[96]An example of a cyanobacterial species that does so isMicrocoleus vaginatus.M. vaginatusstabilizes soil using apolysaccharidesheath that binds to sand particles and absorbs water.[97]M. vaginatusalso makes a significant contribution to the cohesion ofbiological soil crust.[98]

Some of these organisms contribute significantly to global ecology and theoxygen cycle.The tiny marine cyanobacteriumProchlorococcuswas discovered in 1986 and accounts for more than half of the photosynthesis of the open ocean.[99]Circadian rhythmswere once thought to only exist in eukaryotic cells but many cyanobacteria display abacterial circadian rhythm.

"Cyanobacteria are arguably the most successful group ofmicroorganismson earth. They are the most genetically diverse; they occupy a broad range of habitats across all latitudes, widespread in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems, and they are found in the most extreme niches such as hot springs, salt works, and hypersaline bays.Photoautotrophic,oxygen-producing cyanobacteria created the conditions in the planet's early atmosphere that directed the evolution of aerobic metabolism and eukaryotic photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria fulfill vital ecological functions in the world's oceans, being important contributors to global carbon and nitrogen budgets. "– Stewart and Falconer[100]

Cyanobionts

[edit]

Leaf and root colonization by cyanobacteria

(2) On the root surface, cyanobacteria exhibit two types of colonization pattern; in theroot hair,filaments ofAnabaenaandNostocspecies form loose colonies, and in the restricted zone on the root surface, specificNostocspecies form cyanobacterial colonies.

(3) Co-inoculation with2,4-DandNostocspp. increases para-nodule formation and nitrogen fixation. A large number ofNostocspp. isolates colonize the rootendosphereand form para-nodules.[101]

Some cyanobacteria, the so-calledcyanobionts(cyanobacterial symbionts), have asymbioticrelationship with other organisms, both unicellular and multicellular.[102]As illustrated on the right, there are many examples of cyanobacteria interactingsymbioticallywithland plants.[103][104][105][106]Cyanobacteria can enter the plant through thestomataand colonize the intercellular space, forming loops and intracellular coils.[107]Anabaenaspp. colonize the roots of wheat and cotton plants.[108][109][110]Calothrixsp. has also been found on the root system of wheat.[109][110]Monocots,such as wheat and rice, have been colonised byNostocspp.,[111][112][113][114]In 1991, Ganther and others isolated diverseheterocystousnitrogen-fi xing cyanobacteria, includingNostoc,AnabaenaandCylindrospermum,from plant root and soil. Assessment of wheat seedling roots revealed two types of association patterns: loose colonization of root hair byAnabaenaand tight colonization of the root surface within a restricted zone byNostoc.[111][101]

(a)O. magnificuswith numerous cyanobionts present in the upper and lower girdle lists (black arrowheads) of the cingulum termed the symbiotic chamber.

(b)O. steiniiwith numerous cyanobionts inhabiting the symbiotic chamber.

(c) Enlargement of the area in (b) showing two cyanobionts that are being divided by binary transverse fission (white arrows).

The relationships betweencyanobionts(cyanobacterial symbionts) and protistan hosts are particularly noteworthy, as some nitrogen-fi xing cyanobacteria (diazotrophs) play an important role inprimary production,especially in nitrogen-limitedoligotrophicoceans.[115][116][117]Cyanobacteria, mostlypico-sizedSynechococcusandProchlorococcus,are ubiquitously distributed and are the most abundant photosynthetic organisms on Earth, accounting for a quarter of all carbon fixed in marine ecosystems.[39][118][46]In contrast to free-living marine cyanobacteria, some cyanobionts are known to be responsible for nitrogen fixation rather than carbon fixation in the host.[119][120]However, the physiological functions of most cyanobionts remain unknown. Cyanobionts have been found in numerous protist groups, includingdinoflagellates,tintinnids,radiolarians,amoebae,diatoms,andhaptophytes.[121][122]Among these cyanobionts, little is known regarding the nature (e.g., genetic diversity, host or cyanobiont specificity, and cyanobiont seasonality) of the symbiosis involved, particularly in relation to dinoflagellate host.[102]

Collective behaviour

[edit]

Some cyanobacteria – even single-celled ones – show striking collective behaviours and form colonies (orblooms) that can float on water and have important ecological roles. For instance, billions of years ago, communities of marinePaleoproterozoiccyanobacteria could have helped create thebiosphereas we know it by burying carbon compounds and allowing the initial build-up of oxygen in the atmosphere.[124]On the other hand,toxic cyanobacterial bloomsare an increasing issue for society, as their toxins can be harmful to animals.[32]Extreme blooms can also deplete water of oxygen and reduce the penetration of sunlight and visibility, thereby compromising the feeding and mating behaviour of light-reliant species.[123]

As shown in the diagram on the right, bacteria can stay in suspension as individual cells, adhere collectively to surfaces to form biofilms, passively sediment, or flocculate to form suspended aggregates. Cyanobacteria are able to produce sulphatedpolysaccharides(yellow haze surrounding clumps of cells) that enable them to form floating aggregates. In 2021, Maeda et al. discovered that oxygen produced by cyanobacteria becomes trapped in the network of polysaccharides and cells, enabling the microorganisms to form buoyant blooms.[125]It is thought that specific protein fibres known aspili(represented as lines radiating from the cells) may act as an additional way to link cells to each other or onto surfaces. Some cyanobacteria also use sophisticated intracellulargas vesiclesas floatation aids.[123]

The diagram on the left above shows a proposed model of microbial distribution, spatial organization, carbon and O2cycling in clumps and adjacent areas. (a) Clumps contain denser cyanobacterial filaments and heterotrophic microbes. The initial differences in density depend on cyanobacterial motility and can be established over short timescales. Darker blue color outside of the clump indicates higher oxygen concentrations in areas adjacent to clumps. Oxic media increase the reversal frequencies of any filaments that begin to leave the clumps, thereby reducing the net migration away from the clump. This enables the persistence of the initial clumps over short timescales; (b) Spatial coupling between photosynthesis and respiration in clumps. Oxygen produced by cyanobacteria diffuses into the overlying medium or is used for aerobic respiration.Dissolved inorganic carbon(DIC) diffuses into the clump from the overlying medium and is also produced within the clump by respiration. In oxic solutions, high O2concentrations reduce the efficiency of CO2fixation and result in the excretion of glycolate. Under these conditions, clumping can be beneficial to cyanobacteria if it stimulates the retention of carbon and the assimilation of inorganic carbon by cyanobacteria within clumps. This effect appears to promote the accumulation ofparticulate organic carbon(cells, sheaths and heterotrophic organisms) in clumps.[126]

It has been unclear why and how cyanobacteria form communities. Aggregation must divert resources away from the core business of making more cyanobacteria, as it generally involves the production of copious quantities of extracellular material. In addition, cells in the centre of dense aggregates can also suffer from both shading and shortage of nutrients.[127][128]So, what advantage does this communal life bring for cyanobacteria?[123]

New insights into how cyanobacteria form blooms have come from a 2021 study on the cyanobacteriumSynechocystis.These use a set of genes that regulate the production and export of sulphatedpolysaccharides,chains of sugar molecules modified withsulphategroups that can often be found in marine algae and animal tissue. Many bacteria generate extracellular polysaccharides, but sulphated ones have only been seen in cyanobacteria. InSynechocystisthese sulphated polysaccharide help the cyanobacterium form buoyant aggregates by trapping oxygen bubbles in the slimy web of cells and polysaccharides.[125][123]

Previous studies onSynechocystishave showntype IV pili,which decorate the surface of cyanobacteria, also play a role in forming blooms.[130][127]These retractable and adhesive protein fibres are important for motility, adhesion to substrates and DNA uptake.[131]The formation of blooms may require both type IV pili and Synechan – for example, the pili may help to export the polysaccharide outside the cell. Indeed, the activity of these protein fibres may be connected to the production of extracellular polysaccharides in filamentous cyanobacteria.[132]A more obvious answer would be that pili help to build the aggregates by binding the cells with each other or with the extracellular polysaccharide. As with other kinds of bacteria,[133]certain components of the pili may allow cyanobacteria from the same species to recognise each other and make initial contacts, which are then stabilised by building a mass of extracellular polysaccharide.[123]

The bubble flotation mechanism identified by Maeda et al. joins a range of known strategies that enable cyanobacteria to control their buoyancy, such as using gas vesicles or accumulating carbohydrate ballasts.[134]Type IV pili on their own could also control the position of marine cyanobacteria in the water column by regulating viscous drag.[135]Extracellular polysaccharide appears to be a multipurpose asset for cyanobacteria, from floatation device to food storage, defence mechanism and mobility aid.[132][123]

Cellular death

[edit]

One of the most critical processes determining cyanobacterial eco-physiology iscellular death.Evidence supports the existence of controlled cellular demise in cyanobacteria, and various forms of cell death have been described as a response to biotic and abiotic stresses. However, cell death research in cyanobacteria is a relatively young field and understanding of the underlying mechanisms and molecular machinery underpinning this fundamental process remains largely elusive.[25]However, reports on cell death of marine and freshwater cyanobacteria indicate this process has major implications for the ecology of microbial communities/[137][138][139][140]Different forms of cell demise have been observed in cyanobacteria under several stressful conditions,[141][142]and cell death has been suggested to play a key role in developmental processes, such as akinete and heterocyst differentiation, as well as strategy for population survival.[136][143][144][48][25]

Cyanophages

[edit]Cyanophagesare viruses that infect cyanobacteria. Cyanophages can be found in both freshwater and marine environments.[145]Marine and freshwater cyanophages haveicosahedralheads, which contain double-stranded DNA, attached to a tail by connector proteins.[146]The size of the head and tail vary among species of cyanophages. Cyanophages, like otherbacteriophages,rely onBrownian motionto collide with bacteria, and then use receptor binding proteins to recognize cell surface proteins, which leads to adherence. Viruses with contractile tails then rely on receptors found on their tails to recognize highly conserved proteins on the surface of the host cell.[147]

Cyanophages infect a wide range of cyanobacteria and are key regulators of the cyanobacterial populations in aquatic environments, and may aid in the prevention of cyanobacterial blooms in freshwater and marine ecosystems. These blooms can pose a danger to humans and other animals, particularly ineutrophicfreshwater lakes. Infection by these viruses is highly prevalent in cells belonging toSynechococcusspp. in marine environments, where up to 5% of cells belonging to marine cyanobacterial cells have been reported to contain mature phage particles.[148]

The first cyanophage,LPP-1,was discovered in 1963.[149]Cyanophages are classified within thebacteriophagefamiliesMyoviridae(e.g.AS-1,N-1),Podoviridae(e.g. LPP-1) andSiphoviridae(e.g.S-1).[149]

Movement

[edit]

It has long been known thatfilamentous cyanobacteriaperform surface motions, and that these movements result fromtype IV pili.[150][132][151]Additionally,Synechococcus,a marine cyanobacteria, is known to swim at a speed of 25 μm/s by a mechanism different to that of bacterial flagella.[152]Formation of waves on the cyanobacteria surface is thought to push surrounding water backwards.[153][154]Cells are known to bemotileby a gliding method[155]and a novel uncharacterized, non-phototactic swimming method[156]that does not involve flagellar motion.

Many species of cyanobacteria are capable of gliding.Glidingis a form of cell movement that differs from crawling or swimming in that it does not rely on any obvious external organ or change in cell shape and it occurs only in the presence of asubstrate.[157][158]Gliding in filamentous cyanobacteria appears to be powered by a "slime jet" mechanism, in which the cells extrude a gel that expands quickly as it hydrates providing a propulsion force,[159][160]although someunicellularcyanobacteria usetype IV pilifor gliding.[161][22]

Cyanobacteria have strict light requirements. Too little light can result in insufficient energy production, and in some species may cause the cells to resort to heterotrophic respiration.[21]Too much light can inhibit the cells, decrease photosynthesis efficiency and cause damage by bleaching. UV radiation is especially deadly for cyanobacteria, with normal solar levels being significantly detrimental for these microorganisms in some cases.[20][162][22]

Filamentous cyanobacteria that live in microbial mats often migrate vertically and horizontally within the mat in order to find an optimal niche that balances their light requirements for photosynthesis against their sensitivity to photodamage. For example, the filamentous cyanobacteriaOscillatoriasp. andSpirulina subsalsafound in the hypersaline benthic mats ofGuerrero Negro,Mexico migrate downwards into the lower layers during the day in order to escape the intense sunlight and then rise to the surface at dusk.[163]In contrast, the population ofMicrocoleus chthonoplastesfound in hypersaline mats inCamargue,France migrate to the upper layer of the mat during the day and are spread homogeneously through the mat at night.[164]An in vitro experiment usingPhormidium uncinatumalso demonstrated this species' tendency to migrate in order to avoid damaging radiation.[20][162]These migrations are usually the result of some sort of photomovement, although other forms of taxis can also play a role.[165][22]

Photomovement – the modulation of cell movement as a function of the incident light – is employed by the cyanobacteria as a means to find optimal light conditions in their environment. There are three types of photomovement: photokinesis, phototaxis and photophobic responses.[166][167][168][22]

Photokinetic microorganisms modulate their gliding speed according to the incident light intensity. For example, the speed with whichPhormidium autumnaleglides increases linearly with the incident light intensity.[169][22]

Phototactic microorganisms move according to the direction of the light within the environment, such that positively phototactic species will tend to move roughly parallel to the light and towards the light source. Species such asPhormidium uncinatumcannot steer directly towards the light, but rely on random collisions to orient themselves in the right direction, after which they tend to move more towards the light source. Others, such asAnabaena variabilis,can steer by bending the trichome.[170][22]

Finally, photophobic microorganisms respond to spatial and temporal light gradients. A step-up photophobic reaction occurs when an organism enters a brighter area field from a darker one and then reverses direction, thus avoiding the bright light. The opposite reaction, called a step-down reaction, occurs when an organism enters a dark area from a bright area and then reverses direction, thus remaining in the light.[22]

Evolution

[edit]Earth history

[edit]−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stromatolitesare layered biochemicalaccretionarystructuresformed in shallow water by the trapping, binding, and cementation of sedimentary grains bybiofilms(microbial mats) ofmicroorganisms,especially cyanobacteria.[171]

During thePrecambrian,stromatolite communities of microorganisms grew in most marine and non-marine environments in thephotic zone.After the Cambrian explosion of marine animals, grazing on the stromatolite mats by herbivores greatly reduced the occurrence of the stromatolites in marine environments. Since then, they are found mostly in hypersaline conditions where grazing invertebrates cannot live (e.g.Shark Bay,Western Australia). Stromatolites provide ancient records of life on Earth by fossil remains which date from 3.5Gaago.[172]The oldest undisputed evidence of cyanobacteria is dated to be 2.1 Ga ago, but there is some evidence for them as far back as 2.7 Ga ago.[27]Cyanobacteria might have also emerged 3.5 Ga ago.[173]Oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere remained around or below 0.001% of today's level until 2.4 Ga ago (theGreat Oxygenation Event).[174]The rise in oxygen may have caused a fall in the concentration ofatmospheric methane,and triggered theHuronian glaciationfrom around 2.4 to 2.1 Ga ago. In this way, cyanobacteria may have killed off most of the other bacteria of the time.[175]

Oncolitesaresedimentary structurescomposed of oncoids, which are layered structures formed by cyanobacterial growth. Oncolites are similar to stromatolites, but instead of forming columns, they form approximately spherical structures that were not attached to the underlying substrate as they formed.[176]The oncoids often form around a central nucleus, such as a shell fragment,[177]and acalcium carbonatestructure is deposited by encrustingmicrobes.Oncolites are indicators of warm waters in thephotic zone,but are also known in contemporary freshwater environments.[178]These structures rarely exceed 10 cm in diameter.

One former classification scheme of cyanobacterial fossils divided them into theporostromataand thespongiostromata.These are now recognized asform taxaand considered taxonomically obsolete; however, some authors have advocated for the terms remaining informally to describe form and structure of bacterial fossils.[179]

-

Stromatolitesleft behind by cyanobacteria are the oldest known fossils of life on Earth. This fossil is one billion years old.

-

Oncolitic limestone formed from successive layers of calcium carbonate precipitated by cyanobacteria

-

Cyanobacterial remains of an annulated tubularmicrofossilOscillatoriopsis longa [180]

Scale bar: 100 μm

Origin of photosynthesis

[edit]Oxygenic photosynthesisonly evolved once (in prokaryotic cyanobacteria), and all photosyntheticeukaryotes(including allplantsandalgae) have acquired this ability fromendosymbiosiswith cyanobacteria or theirendosymbionthosts. In other words, all the oxygen that makes the atmosphere breathable foraerobic organismsoriginally comes from cyanobacteria or theirplastiddescendants.[181]

Cyanobacteria remained the principalprimary producersthroughout the latter half of theArcheaneonand most of theProterozoic eon,in part because the redox structure of the oceans favored photoautotrophs capable ofnitrogen fixation.However, their population is argued to have varied considerably across this eon.[10][182][183]Archaeplastidssuch asgreenandred algaeeventually surpassed cyanobacteria as major primary producers oncontinental shelvesnear the end of theNeoproterozoic,but only with theMesozoic(251–65 Ma) radiations of secondary photoautotrophs such asdinoflagellates,coccolithophoridsanddiatomsdidprimary productionin marine shelf waters take modern form. Cyanobacteria remain critical tomarine ecosystemsas primary producers in oceanic gyres, as agents of biological nitrogen fixation, and, in modified form, as the plastids ofmarine algae.[184]

Origin of chloroplasts

[edit]Primary chloroplasts are cell organelles found in someeukaryoticlineages, where they are specialized in performing photosynthesis. They are considered to have evolved fromendosymbioticcyanobacteria.[185][186]After some years of debate,[187]it is now generally accepted that the three major groups of primary endosymbiotic eukaryotes (i.e.green plants,red algaeandglaucophytes) form one largemonophyletic groupcalledArchaeplastida,which evolved after one unique endosymbiotic event.[188][189][190][191]

Themorphologicalsimilarity between chloroplasts and cyanobacteria was first reported by German botanistAndreas Franz Wilhelm Schimperin the 19th century[192]Chloroplasts are only found inplantsandalgae,[193]thus paving the way for Russian biologistKonstantin Mereschkowskito suggest in 1905 the symbiogenic origin of the plastid.[194]Lynn Margulisbrought this hypothesis back to attention more than 60 years later[195]but the idea did not become fully accepted until supplementary data started to accumulate. The cyanobacterial origin of plastids is now supported by various pieces ofphylogenetic,[196][188][191]genomic,[197]biochemical[198][199]and structural evidence.[200]The description of another independent and more recent primary endosymbiosis event between a cyanobacterium and a separate eukaryote lineage (therhizarianPaulinellachromatophora) also gives credibility to the endosymbiotic origin of the plastids.[201]

In addition to this primary endosymbiosis, many eukaryotic lineages have been subject tosecondaryor eventertiary endosymbiotic events,that is the "Matryoshka-like "engulfment by a eukaryote of another plastid-bearing eukaryote.[203][185]

Chloroplastshave many similarities with cyanobacteria, including a circularchromosome,prokaryotic-typeribosomes,and similar proteins in the photosynthetic reaction center.[204][205]Theendosymbiotic theorysuggests that photosynthetic bacteria were acquired (byendocytosis) by earlyeukaryoticcells to form the firstplantcells. Therefore, chloroplasts may be photosynthetic bacteria that adapted to life inside plant cells. Likemitochondria,chloroplasts still possess their own DNA, separate from thenuclear DNAof their plant host cells and the genes in this chloroplast DNA resemble those in cyanobacteria.[206]DNA in chloroplasts codes forredoxproteins such as photosynthetic reaction centers. TheCoRR hypothesisproposes this co-location is required for redox regulation.

Marine origins

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

Cyanobacteria have fundamentally transformed the geochemistry of the planet.[210][207]Multiple lines of geochemical evidence support the occurrence of intervals of profound global environmental change at the beginning and end of theProterozoic(2,500–542 Mya).[211] [212][213]While it is widely accepted that the presence of molecular oxygen in the early fossil record was the result of cyanobacteria activity, little is known about how cyanobacteria evolution (e.g., habitat preference) may have contributed to changes inbiogeochemical cyclesthrough Earth history. Geochemical evidence has indicated that there was a first step-increase in the oxygenation of the Earth's surface, which is known as theGreat Oxidation Event(GOE), in the earlyPaleoproterozoic(2,500–1,600 Mya).[210][207]A second but much steeper increase in oxygen levels, known as the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (NOE),[212][81][214]occurred at around 800 to 500 Mya.[213][215]Recentchromiumisotope data point to low levels of atmospheric oxygen in the Earth's surface during the mid-Proterozoic,[211]which is consistent with the late evolution of marine planktonic cyanobacteria during theCryogenian;[216]both types of evidence help explain the late emergence and diversification of animals.[217][43]

Understanding the evolution of planktonic cyanobacteria is important because their origin fundamentally transformed thenitrogenandcarbon cyclestowards the end of thePre-Cambrian.[215]It remains unclear, however, what evolutionary events led to the emergence of open-ocean planktonic forms within cyanobacteria and how these events relate to geochemical evidence during the Pre-Cambrian.[212]So far, it seems that ocean geochemistry (e.g.,euxinicconditions during the early- to mid-Proterozoic)[212][214][218]and nutrient availability [219]likely contributed to the apparent delay in diversification and widespread colonization of open ocean environments by planktonic cyanobacteria during theNeoproterozoic.[215][43]

Genetics

[edit]Cyanobacteria are capable of natural genetictransformation.[220][221][222]Natural genetic transformation is the genetic alteration of a cell resulting from the direct uptake and incorporation of exogenous DNA from its surroundings. For bacterial transformation to take place, the recipient bacteria must be in a state ofcompetence,which may occur in nature as a response to conditions such as starvation, high cell density or exposure to DNA damaging agents. In chromosomal transformation, homologous transforming DNA can be integrated into the recipient genome byhomologous recombination,and this process appears to be an adaptation forrepairing DNA damage.[223]

DNA repair

[edit]Cyanobacteria are challenged by environmental stresses and internally generatedreactive oxygen speciesthat causeDNA damage.Cyanobacteria possess numerousE. coli-likeDNA repairgenes.[224]Several DNA repair genes are highly conserved in cyanobacteria, even in smallgenomes,suggesting that core DNA repair processes such asrecombinational repair,nucleotide excision repairand methyl-directedDNA mismatch repairare common among cyanobacteria.[224]

Classification

[edit]Phylogeny

[edit]| 16S rRNA basedLTP_12_2021[225][226][227] | GTDB 08-RS214 byGenome Taxonomy Database[228][229][230] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Taxonomy

[edit]

Historically, bacteria were first classified as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes, which along with the Schizophyceae (blue-green algae/Cyanobacteria) formed the phylum Schizophyta,[231]then in the phylumMonerain the kingdomProtistabyHaeckelin 1866, comprisingProtogens, Protamaeba, Vampyrella, Protomonae,andVibrio,but notNostocand other cyanobacteria, which were classified with algae,[232]later reclassified as theProkaryotesbyChatton.[233]

The cyanobacteria were traditionally classified by morphology into five sections, referred to by the numerals I–V. The first three –Chroococcales,Pleurocapsales,andOscillatoriales– are not supported by phylogenetic studies. The latter two –NostocalesandStigonematales– are monophyletic as a unit, and make up the heterocystous cyanobacteria.[234][235]

The members of Chroococales are unicellular and usually aggregate in colonies. The classic taxonomic criterion has been the cell morphology and the plane of cell division. In Pleurocapsales, the cells have the ability to form internal spores (baeocytes). The rest of the sections include filamentous species. In Oscillatoriales, the cells are uniseriately arranged and do not form specialized cells (akinetes and heterocysts).[236]In Nostocales and Stigonematales, the cells have the ability to develop heterocysts in certain conditions. Stigonematales, unlike Nostocales, include species with truly branched trichomes.[234]

Most taxa included in the phylum or division Cyanobacteria have not yet been validly published underThe International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes(ICNP) except:

- The classesChroobacteria,Hormogoneae,andGloeobacteria

- The ordersChroococcales,Gloeobacterales,Nostocales,Oscillatoriales,Pleurocapsales,andStigonematales

- The familiesProchloraceaeandProchlorotrichaceae

- The generaHalospirulina,Planktothricoides,Prochlorococcus,Prochloron,andProchlorothrix

The remainder are validly published under theInternational Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants.

Formerly, some bacteria, likeBeggiatoa,were thought to be colorless Cyanobacteria.[237]

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on theList of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature(LPSN)[238]andNational Center for Biotechnology Information(NCBI).[239] Class "Cyanobacteriia"

- Subclass "Gloeobacteria"Cavalier-Smith 2002

- GloeobacteralesCavalier-Smith 2002

- Subclass "Phycobacteria"Cavalier-Smith 2002

- AcaryochloridalesMiyashita et al. 2003 ex Strunecký & Mareš 2022[incl. Thermosynechococcales]

- AegeococcalesStrunecký & Mareš 2022

- "Elainellales"

- "Eurycoccales"

- GeitlerinematalesStrunecký & Mareš 2022

- GloeoemargaritalesMoreira et al. 2016

- "Leptolyngbyales"Strunecký & Mareš 2022

- NodosilinealesStrunecký & Mareš 2022

- OculatellalesStrunecký & Mareš 2022

- "Phormidesmiales"

- ProchlorococcaceaeKomárek & Strunecky 2020{ "PCC-6307" }

- PseudanabaenalesHoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- "Pseudophormidiales"

- ThermostichalesKomárek & Strunecký 2020

- SynechococcophycidaeHoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- "Limnotrichales"

- ProchlorotrichalesStrunecký & Mareš 2022(PCC-9006)

- SynechococcalesHoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- NostocophycidaeHoffmann, Komárek & Kastovsky 2005

- CyanobacterialesRippka & Cohen-Bazire 1983(Chamaesiphonales,Chroococcales,Chroococcidiopsidales,Nostocales,Oscillatoriales,Pleurocapsales,Spirulinales,Stigonematales)

Relation to humans

[edit]Biotechnology

[edit]

The unicellular cyanobacteriumSynechocystissp. PCC6803 was the third prokaryote and first photosynthetic organism whosegenomewas completelysequenced.[240]It continues to be an important model organism.[241]CyanotheceATCC 51142 is an importantdiazotrophicmodel organism. The smallest genomes have been found inProchlorococcusspp. (1.7Mb)[242][243]and the largest inNostoc punctiforme(9 Mb).[144]Those ofCalothrixspp. are estimated at 12–15 Mb,[244]as large asyeast.

Recent research has suggested the potential application of cyanobacteria to the generation ofrenewable energyby directly converting sunlight into electricity. Internal photosynthetic pathways can be coupled to chemical mediators that transfer electrons to externalelectrodes.[245][246]In the shorter term, efforts are underway to commercializealgae-based fuelssuch asdiesel,gasoline,andjet fuel.[68][247][248]Cyanobacteria have been also engineered to produce ethanol[249]and experiments have shown that when one or two CBB genes are being over expressed, the yield can be even higher.[250][251]

Cyanobacteria may possess the ability to produce substances that could one day serve as anti-inflammatory agents and combat bacterial infections in humans.[252]Cyanobacteria's photosynthetic output of sugar and oxygen has been demonstrated to have therapeutic value in rats with heart attacks.[253]While cyanobacteria can naturally produce various secondary metabolites, they can serve as advantageous hosts for plant-derived metabolites production owing to biotechnological advances in systems biology and synthetic biology.[254]

Spirulina's extracted blue color is used as a natural food coloring.[255]

Researchers from several space agencies argue that cyanobacteria could be used for producing goods for human consumption in future crewed outposts on Mars, by transforming materials available on this planet.[256]

Human nutrition

[edit]

Some cyanobacteria are sold as food, notablyArthrospira platensis(Spirulina) and others(Aphanizomenon flos-aquae).[257]

Somemicroalgaecontain substances of high biological value, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids, amino acids, proteins, pigments, antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals.[258]Edible blue-green algae reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting NF-κB pathway in macrophages and splenocytes.[259]Sulfate polysaccharides exhibit immunomodulatory, antitumor, antithrombotic, anticoagulant, anti-mutagenic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and even antiviral activity against HIV, herpes, and hepatitis.[260]

Health risks

[edit]Some cyanobacteria can produceneurotoxins,cytotoxins,endotoxins,andhepatotoxins(e.g., themicrocystin-producing bacteria genusmicrocystis), which are collectively known ascyanotoxins.

Specific toxins includeanatoxin-a,guanitoxin,aplysiatoxin,cyanopeptolin,cylindrospermopsin,domoic acid,nodularin R(fromNodularia),neosaxitoxin,andsaxitoxin.Cyanobacteria reproduce explosively under certain conditions. This results inalgal bloomswhich can becomeharmful to other speciesand pose a danger to humans and animals if the cyanobacteria involved produce toxins. Several cases of human poisoning have been documented, but a lack of knowledge prevents an accurate assessment of the risks,[261][262][263][264]and research byLinda Lawton,FRSEatRobert Gordon University,Aberdeen and collaborators has 30 years of examining the phenomenon and methods of improving water safety.[265]

Recent studies suggest that significant exposure to high levels of cyanobacteria producing toxins such asBMAAcan causeamyotrophic lateral sclerosis(ALS). People living within half a mile of cyanobacterially contaminated lakes have had a 2.3 times greater risk of developing ALS than the rest of the population; people around New Hampshire'sLake Mascomahad an up to 25 times greater risk of ALS than the expected incidence.[266]BMAA from desert crusts found throughout Qatar might have contributed to higher rates of ALS inGulf Warveterans.[262][267]

Chemical control

[edit]Several chemicals can eliminate cyanobacterial blooms from smaller water-based systems such as swimming pools. They includecalcium hypochlorite,copper sulphate,Cupricide (chelated copper), andsimazine.[268]The calcium hypochlorite amount needed varies depending on the cyanobacteria bloom, and treatment is needed periodically. According to the Department of Agriculture Australia, a rate of 12 g of 70% material in 1000 L of water is often effective to treat a bloom.[268]Copper sulfate is also used commonly, but no longer recommended by the Australian Department of Agriculture, as it kills livestock, crustaceans, and fish.[268]Cupricide is a chelated copper product that eliminates blooms with lower toxicity risks than copper sulfate. Dosage recommendations vary from 190 mL to 4.8 L per 1000 m2.[268]Ferric alum treatments at the rate of 50 mg/L will reduce algae blooms.[268][269]Simazine, which is also a herbicide, will continue to kill blooms for several days after an application. Simazine is marketed at different strengths (25, 50, and 90%), the recommended amount needed for one cubic meter of water per product is 25% product 8 mL; 50% product 4 mL; or 90% product 2.2 mL.[268]

Climate change

[edit]Climate changeis likely to increase the frequency, intensity and duration of cyanobacterial blooms in manyeutrophiclakes, reservoirs and estuaries.[270][32]Bloom-forming cyanobacteria produce a variety ofneurotoxins,hepatotoxinsanddermatoxins,which can be fatal to birds and mammals (including waterfowl, cattle and dogs) and threaten the use of waters for recreation, drinking water production, agricultural irrigation and fisheries.[32]Toxic cyanobacteriahave caused major water quality problems, for example inLake Taihu(China),Lake Erie(USA),Lake Okeechobee(USA),Lake Victoria(Africa) and theBaltic Sea.[32][271][272][273]

Climate changefavours cyanobacterial blooms both directly and indirectly.[32]Many bloom-forming cyanobacteria can grow at relatively high temperatures.[274]Increasedthermal stratificationof lakes and reservoirs enables buoyant cyanobacteria to float upwards and form dense surface blooms, which gives them better access to light and hence a selective advantage over nonbuoyant phytoplankton organisms.[275][93]Protracted droughts during summer increase water residence times in reservoirs, rivers and estuaries, and these stagnant warm waters can provide ideal conditions for cyanobacterial bloom development.[276][273]

The capacity of the harmful cyanobacterial genusMicrocystisto adapt to elevated CO2levels was demonstrated in both laboratory and field experiments.[277]Microcystisspp. take up CO2andHCO−

3and accumulateinorganic carbonincarboxysomes,and strain competitiveness was found to depend on the concentration of inorganic carbon. As a result,climate changeand increased CO2levels are expected to affect the strain composition of cyanobacterial blooms.[277][273]

Gallery

[edit]-

Cyanobacteria activity turnsCoatepeque Calderalake a turquoise color

-

Cyanobacterial bloom nearFiji

-

Cyanobacteria inLake Köyliö.

-

Video –OscillatoriaandGleocapsa– with oscillatory movement as filaments ofOscillatoriaorient towards light

See also

[edit]- Archean Eon

- Bacterial phyla,other major lineages of Bacteria

- Biodiesel

- Cyanobiont

- Endosymbiotic theory

- Geological history of oxygen

- Hypolith

Notes

[edit]- ^Botanists restrict the namealgaetoprotisteukaryotes,which does not extend to cyanobacteria, which areprokaryotes.However, the common name blue-green algae continues to be used synonymously with cyanobacteria outside of the biological sciences.

References

[edit]- ^Silva PC, Moe RL (December 2019)."Cyanophyceae".AccessScience.McGraw Hill Education.doi:10.1036/1097-8542.175300.Retrieved21 April2011.

- ^Oren A (September 2004)."A proposal for further integration of the cyanobacteria under the Bacteriological Code".International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology.54(Pt 5): 1895–1902.doi:10.1099/ijs.0.03008-0.PMID15388760.

- ^Komárek J, Kaštovský J, Mareš J, Johansen JR (2014)."Taxonomic classification of cyanoprokaryotes (cyanobacterial genera) 2014, using a polyphasic approach"(PDF).Preslia.86:295–335.

- ^Sinha RP, Häder DP (2008). "UV-protectants in cyanobacteria".Plant Science.174(3): 278–289.Bibcode:2008PlnSc.174..278S.doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.12.004.

- ^Harper, Douglas."cyan".Online Etymology Dictionary.Retrieved21 January2018.

- ^κύανος.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;A Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.

- ^"Life History and Ecology of Cyanobacteria".University of California Museum of Paleontology.Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2012.Retrieved17 July2012.

- ^"Taxonomy Browser – Cyanobacteria".National Center for Biotechnology Information.NCBI:txid1117.Retrieved12 April2018.

- ^Allaby M, ed. (1992). "Algae".The Concise Dictionary of Botany.Oxford:Oxford University Press.

- ^abCrockford PW, Bar On YM, Ward LM, Milo R, Halevy I (November 2023). "The geologic history of primary productivity".Current Biology.33(21): 4741–4750.e5.Bibcode:2023CBio...33E4741C.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.09.040.PMID37827153.S2CID263839383.

- ^Stal LJ, Cretoiu MS (2016).The Marine Microbiome: An Untapped Source of Biodiversity and Biotechnological Potential.Springer Science+Business Media.ISBN978-3319330006.

- ^Whitton BA, ed. (2012)."The fossil record of cyanobacteria".Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time.Springer Science+Business Media.p. 17.ISBN978-94-007-3855-3.

- ^"Bacteria".Basic Biology. 18 March 2016.

- ^Liberton M, Pakrasi HB (2008). "Chapter 10. Membrane Systems in Cyanobacteria". In Herrero A, Flore E (eds.).The Cyanobacteria: Molecular Biology, Genomics, and Evolution.Norwich, United Kingdom:Horizon Scientific Press.pp. 217–287.ISBN978-1-904455-15-8.

- ^Liberton M, Page LE, O'Dell WB, O'Neill H, Mamontov E, Urban VS, Pakrasi HB (February 2013)."Organization and flexibility of cyanobacterial thylakoid membranes examined by neutron scattering".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.288(5): 3632–3640.doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.416933.PMC3561581.PMID23255600.

- ^Monchamp ME, Spaak P, Pomati F (27 July 2019)."Long Term Diversity and Distribution of Non-photosynthetic Cyanobacteria in Peri-Alpine Lakes".Frontiers in Microbiology.9:3344.doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03344.PMC6340189.PMID30692982.

- ^Pathak J, Rajneesh, Maurya PK, Singh SP, Haeder DP, Sinha RP (2018)."Cyanobacterial Farming for Environment Friendly Sustainable Agriculture Practices: Innovations and Perspectives".Frontiers in Environmental Science.6.doi:10.3389/fenvs.2018.00007.ISSN2296-665X.

- ^Morrison J (11 January 2016)."Living Bacteria Are Riding Earth's Air Currents".Smithsonian Magazine.Retrieved10 August2022.

- ^Whitton BA, Potts M (2012). "Introduction to the Cyanobacteria". In Whitton BA (ed.).Ecology of Cyanobacteria II.pp. 1–13.doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3855-3_1.ISBN978-94-007-3854-6.

- ^abcTamulonis C, Postma M, Kaandorp J (2011)."Modeling filamentous cyanobacteria reveals the advantages of long and fast trichomes for optimizing light exposure".PLOS ONE.6(7): e22084.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622084T.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022084.PMC3138769.PMID21789215.

- ^abStay LJ (5 July 2012)."Cyanobacterial Mats and Stromatolites".In Whitton BA (ed.).Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time.Springer Science & Business Media.ISBN9789400738553.Retrieved15 February2022– via Google Books.

- ^abcdefghTamulonis C, Postma M, Kaandorp J (2011)."Modeling filamentous cyanobacteria reveals the advantages of long and fast trichomes for optimizing light exposure".PLOS ONE.6(7): e22084.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622084T.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022084.PMC3138769.PMID21789215.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^Weiss KR (30 July 2006)."A Primeval Tide of Toxins".Los Angeles Times.Archived fromthe originalon 14 August 2006.

- ^Dodds WK, Gudder DA, Mollenhauer D (1995). "The ecology of 'Nostoc'".Journal of Phycology.31(1): 2–18.Bibcode:1995JPcgy..31....2D.doi:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1995.00002.x.S2CID85011483.

- ^abcdefAguilera A, Klemenčič M, Sueldo DJ, Rzymski P, Giannuzzi L, Martin MV (2021)."Cell Death in Cyanobacteria: Current Understanding and Recommendations for a Consensus on Its Nomenclature".Frontiers in Microbiology.12:631654.doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.631654.PMC7965980.PMID33746925.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^Raven RA (5 July 2012). "Physiological Ecology: Carbon". In Whitton BA (ed.).Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time.Springer. p. 442.ISBN9789400738553.

- ^abSchirrmeister BE, de Vos JM, Antonelli A, Bagheri HC (January 2013)."Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(5): 1791–1796.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1791S.doi:10.1073/pnas.1209927110.PMC3562814.PMID23319632.

- ^Bullerjahn GS, Post AF (2014)."Physiology and molecular biology of aquatic cyanobacteria".Frontiers in Microbiology.5:359.doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00359.PMC4099938.PMID25076944.

- ^Tang W, Wang S, Fonseca-Batista D, Dehairs F, Gifford S, Gonzalez AG, et al. (February 2019)."Revisiting the distribution of oceanic N2fixation and estimating diazotrophic contribution to marine production ".Nature Communications.10(1): 831.doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08640-0.PMC6381160.PMID30783106.

- ^Bláha L, Babica P, Maršálek B (June 2009)."Toxins produced in cyanobacterial water blooms - toxicity and risks".Interdisciplinary Toxicology.2(2): 36–41.doi:10.2478/v10102-009-0006-2.PMC2984099.PMID21217843.

- ^Paerl HW, Otten TG (May 2013). "Harmful cyanobacterial blooms: causes, consequences, and controls".Microbial Ecology.65(4): 995–1010.Bibcode:2013MicEc..65..995P.doi:10.1007/s00248-012-0159-y.PMID23314096.S2CID5718333.

- ^abcdefHuisman J, Codd GA, Paerl HW, Ibelings BW, Verspagen JM, Visser PM (August 2018). "Cyanobacterial blooms".Nature Reviews. Microbiology.16(8): 471–483.doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0040-1.PMID29946124.S2CID49427202.

- ^Field CB, Behrenfeld MJ, Randerson JT, Falkowski P (July 1998)."Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components".Science.281(5374): 237–240.Bibcode:1998Sci...281..237F.doi:10.1126/science.281.5374.237.PMID9657713.

- ^Cabello-Yeves PJ, Scanlan DJ, Callieri C, Picazo A, Schallenberg L, Huber P, et al. (October 2022)."α-cyanobacteria possessing form IA RuBisCO globally dominate aquatic habitats".The ISME Journal.16(10). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 2421–2432.Bibcode:2022ISMEJ..16.2421C.doi:10.1038/s41396-022-01282-z.PMC9477826.PMID35851323.

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^abZehr JP (April 2011). "Nitrogen fixation by marine cyanobacteria".Trends in Microbiology.19(4): 162–173.doi:10.1016/j.tim.2010.12.004.PMID21227699.

- ^abThompson AW, Foster RA, Krupke A, Carter BJ, Musat N, Vaulot D, et al. (September 2012). "Unicellular cyanobacterium symbiotic with a single-celled eukaryotic alga".Science.337(6101): 1546–1550.Bibcode:2012Sci...337.1546T.doi:10.1126/science.1222700.PMID22997339.S2CID7071725.

- ^abJohnson ZI, Zinser ER, Coe A, McNulty NP, Woodward EM, Chisholm SW (March 2006). "Niche partitioning among Prochlorococcus ecotypes along ocean-scale environmental gradients".Science.311(5768): 1737–1740.Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1737J.doi:10.1126/science.1118052.PMID16556835.S2CID3549275.

- ^abScanlan DJ, Ostrowski M, Mazard S, Dufresne A, Garczarek L, Hess WR, et al. (June 2009)."Ecological genomics of marine picocyanobacteria".Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews.73(2): 249–299.doi:10.1128/MMBR.00035-08.PMC2698417.PMID19487728.

- ^abFlombaum P, Gallegos JL, Gordillo RA, Rincón J, Zabala LL, Jiao N, et al. (June 2013)."Present and future global distributions of the marine Cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(24): 9824–9829.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.9824F.doi:10.1073/pnas.1307701110.PMC3683724.PMID23703908.

- ^Foster RA, Kuypers MM, Vagner T, Paerl RW, Musat N, Zehr JP (September 2011)."Nitrogen fixation and transfer in open ocean diatom-cyanobacterial symbioses".The ISME Journal.5(9): 1484–1493.Bibcode:2011ISMEJ...5.1484F.doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.26.PMC3160684.PMID21451586.

- ^Villareal TA (1990). "Laboratory Culture and Preliminary Characterization of the Nitrogen-Fi xing Rhizosolenia-Richelia Symbiosis".Marine Ecology.11(2): 117–132.Bibcode:1990MarEc..11..117V.doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.1990.tb00233.x.

- ^Janson S, Wouters J, Bergman B, Carpenter EJ (October 1999). "Host specificity in the Richelia-diatom symbiosis revealed by hetR gene sequence analysis".Environmental Microbiology.1(5): 431–438.Bibcode:1999EnvMi...1..431J.doi:10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00053.x.PMID11207763.

- ^abcdeSánchez-Baracaldo P (December 2015)."Origin of marine planktonic cyanobacteria".Scientific Reports.5:17418.Bibcode:2015NatSR...517418S.doi:10.1038/srep17418.PMC4665016.PMID26621203.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under aCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^Kettler GC, Martiny AC, Huang K, Zucker J, Coleman ML, Rodrigue S, et al. (December 2007)."Patterns and implications of gene gain and loss in the evolution of Prochlorococcus".PLOS Genetics.3(12): e231.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030231.PMC2151091.PMID18159947.

- ^Nemiroff R, Bonnell J, eds. (27 September 2006)."Earth from Saturn".Astronomy Picture of the Day.NASA.

- ^abPartensky F, Hess WR, Vaulot D (March 1999)."Prochlorococcus, a marine photosynthetic prokaryote of global significance".Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews.63(1): 106–127.doi:10.1128/MMBR.63.1.106-127.1999.PMC98958.PMID10066832.

- ^"The Most Important Microbe You've Never Heard Of".npr.org.

- ^abClaessen D, Rozen DE, Kuipers OP, Søgaard-Andersen L, van Wezel GP (February 2014)."Bacterial solutions to multicellularity: a tale of biofilms, filaments and fruiting bodies"(PDF).Nature Reviews. Microbiology.12(2): 115–124.doi:10.1038/nrmicro3178.hdl:11370/0db66a9c-72ef-4e11-a75d-9d1e5827573d.PMID24384602.S2CID20154495.

- ^Nürnberg DJ, Mariscal V, Parker J, Mastroianni G, Flores E, Mullineaux CW (March 2014). "Branching and intercellular communication in the Section V cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus, a complex multicellular prokaryote".Molecular Microbiology.91(5): 935–949.doi:10.1111/mmi.12506.hdl:10261/99110.PMID24383541.S2CID25479970.

- ^Herrero A, Stavans J, Flores E (November 2016). "The multicellular nature of filamentous heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria".FEMS Microbiology Reviews.40(6): 831–854.doi:10.1093/femsre/fuw029.hdl:10261/140753.PMID28204529.

- ^Risser DD, Chew WG, Meeks JC (April 2014)."Genetic characterization of the hmp locus, a chemotaxis-like gene cluster that regulates hormogonium development and motility in Nostoc punctiforme".Molecular Microbiology.92(2): 222–233.doi:10.1111/mmi.12552.PMID24533832.S2CID37479716.

- ^Khayatan B, Bains DK, Cheng MH, Cho YW, Huynh J, Kim R, et al. (May 2017)."A Putative O-Linked β-N-Acetylglucosamine Transferase Is Essential for Hormogonium Development and Motility in the Filamentous Cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme ".Journal of Bacteriology.199(9): e00075–17.doi:10.1128/JB.00075-17.PMC5388816.PMID28242721.

- ^Esteves-Ferreira AA, Cavalcanti JH, Vaz MG, Alvarenga LV, Nunes-Nesi A, Araújo WL (2017)."Cyanobacterial nitrogenases: phylogenetic diversity, regulation and functional predictions".Genetics and Molecular Biology.40(1 suppl 1): 261–275.doi:10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2016-0050.PMC5452144.PMID28323299.

- ^Meeks JC, Elhai J, Thiel T, Potts M, Larimer F, Lamerdin J, et al. (2001). "An overview of the genome of Nostoc punctiforme, a multicellular, symbiotic cyanobacterium".Photosynthesis Research.70(1): 85–106.doi:10.1023/A:1013840025518.PMID16228364.S2CID8752382.

- ^abGolden JW, Yoon HS (December 1998). "Heterocyst formation in Anabaena".Current Opinion in Microbiology.1(6): 623–629.doi:10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80106-9.PMID10066546.

- ^abcFay P (June 1992)."Oxygen relations of nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria".Microbiological Reviews.56(2): 340–373.doi:10.1128/MMBR.56.2.340-373.1992.PMC372871.PMID1620069.

- ^Singh V, Pande PC, Jain DK (eds.)."Cyanobacteria, Actinomycetes, Mycoplasma, and Rickettsias".Text Book of Botany Diversity of Microbes And Cryptogams.Rastogi Publications. p. 72.ISBN978-8171338894.

- ^"Differences between Bacteria and Cyanobacteria".Microbiology Notes.29 October 2015.Retrieved21 January2018.

- ^Walsby AE (March 1994)."Gas vesicles".Microbiological Reviews.58(1): 94–144.doi:10.1128/MMBR.58.1.94-144.1994.PMC372955.PMID8177173.

- ^

Sims GK, Dunigan EP (1984). "Diurnal and seasonal variations in nitrogenase activityC

2H

2reduction) of rice roots ".Soil Biology and Biochemistry.16:15–18.doi:10.1016/0038-0717(84)90118-4. - ^Bocchi S, Malgioglio A (2010)."Azolla-Anabaena as a Biofertilizer for Rice Paddy Fields in the Po Valley, a Temperate Rice Area in Northern Italy".International Journal of Agronomy.2010:1–5.doi:10.1155/2010/152158.hdl:2434/149583.

- ^Huokko T, Ni T, Dykes GF, Simpson DM, Brownridge P, Conradi FD, et al. (June 2021)."Probing the biogenesis pathway and dynamics of thylakoid membranes".Nature Communications.12(1): 3475.Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.3475H.doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23680-1.PMC8190092.PMID34108457.

- ^Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC (2010)."Bacterial microcompartments".Annual Review of Microbiology.64(1): 391–408.doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134211.PMC6022854.PMID20825353.

- ^Rae BD, Long BM, Badger MR, Price GD (September 2013)."Functions, compositions, and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria".Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews.77(3): 357–379.doi:10.1128/MMBR.00061-12.PMC3811607.PMID24006469.

- ^Long BM, Badger MR, Whitney SM, Price GD (October 2007)."Analysis of carboxysomes from Synechococcus PCC7942 reveals multiple Rubisco complexes with carboxysomal proteins CcmM and CcaA".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.282(40): 29323–29335.doi:10.1074/jbc.M703896200.PMID17675289.

- ^Vothknecht UC, Westhoff P (December 2001)."Biogenesis and origin of thylakoid membranes".Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research.1541(1–2): 91–101.doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(01)00153-7.PMID11750665.

- ^Sobiechowska-Sasim M, Stoń-Egiert J, Kosakowska A (February 2014)."Quantitative analysis of extracted phycobilin pigments in cyanobacteria-an assessment of spectrophotometric and spectrofluorometric methods".Journal of Applied Phycology.26(5): 2065–2074.Bibcode:2014JAPco..26.2065S.doi:10.1007/s10811-014-0244-3.PMC4200375.PMID25346572.

- ^abPisciotta JM, Zou Y, Baskakov IV (May 2010). Yang CH (ed.)."Light-dependent electrogenic activity of cyanobacteria".PLOS ONE.5(5): e10821.Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510821P.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010821.PMC2876029.PMID20520829.

- ^abcVermaas WF (2001). "Photosynthesis and Respiration in Cyanobacteria".Photosynthesis and Respiration in Cyanobacteria. eLS.John Wiley & Sons,Ltd.doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001670.ISBN978-0-470-01590-2.S2CID19016706.

- ^Armstronf JE (2015).How the Earth Turned Green: A Brief 3.8-Billion-Year History of Plants.TheUniversity of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-06977-7.

- ^Klatt JM, de Beer D, Häusler S, Polerecky L (2016)."Cyanobacteria in Sulfidic Spring Microbial Mats Can Perform Oxygenic and Anoxygenic Photosynthesis Simultaneously during an Entire Diurnal Period".Frontiers in Microbiology.7:1973.doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01973.PMC5156726.PMID28018309.

- ^Grossman AR, Schaefer MR, Chiang GG, Collier JL (September 1993)."The phycobilisome, a light-harvesting complex responsive to environmental conditions".Microbiological Reviews.57(3): 725–749.doi:10.1128/MMBR.57.3.725-749.1993.PMC372933.PMID8246846.

- ^"Colors from bacteria | Causes of Color".webexhibits.org.Retrieved22 January2018.

- ^Garcia-Pichel F (2009). "Cyanobacteria". In Schaechter M (ed.).Encyclopedia of Microbiology(third ed.). pp. 107–24.doi:10.1016/B978-012373944-5.00250-9.ISBN978-0-12-373944-5.

- ^Kehoe DM (May 2010)."Chromatic adaptation and the evolution of light color sensing in cyanobacteria".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.107(20): 9029–9030.Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9029K.doi:10.1073/pnas.1004510107.PMC2889117.PMID20457899.

- ^Kehoe DM, Gutu A (2006). "Responding to color: the regulation of complementary chromatic adaptation".Annual Review of Plant Biology.57:127–150.doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105215.PMID16669758.

- ^Palenik B, Haselkorn R (January 1992). "Multiple evolutionary origins of prochlorophytes, the chlorophyll b-containing prokaryotes".Nature.355(6357): 265–267.Bibcode:1992Natur.355..265P.doi:10.1038/355265a0.PMID1731224.S2CID4244829.

- ^Urbach E, Robertson DL, Chisholm SW (January 1992). "Multiple evolutionary origins of prochlorophytes within the cyanobacterial radiation".Nature.355(6357): 267–270.Bibcode:1992Natur.355..267U.doi:10.1038/355267a0.PMID1731225.S2CID2011379.

- ^Cohen Y, Jørgensen BB, Revsbech NP, Poplawski R (February 1986)."Adaptation to Hydrogen Sulfide of Oxygenic and Anoxygenic Photosynthesis among Cyanobacteria".Applied and Environmental Microbiology.51(2): 398–407.Bibcode:1986ApEnM..51..398C.doi:10.1128/AEM.51.2.398-407.1986.PMC238881.PMID16346996.

- ^Blankenship RE(2014).Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis.Wiley-Blackwell.pp. 147–73.ISBN978-1-4051-8975-0.

- ^abOch LM, Shields-Zhou GA (January 2012). "The Neoproterozoic oxygenation event: Environmental perturbations and biogeochemical cycling".Earth-Science Reviews.110(1–4): 26–57.Bibcode:2012ESRv..110...26O.doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.09.004.

- ^Adams DG, Bergman B, Nierzwicki-Bauer SA, Duggan PS, Rai AN, Schüßler A (2013). "Cyanobacterial-Plant Symbioses". In Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F (eds.).The Prokaryotes.Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 359–400.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30194-0_17.ISBN978-3-642-30193-3.

- ^Zhang S, Bryant DA (December 2011). "The tricarboxylic acid cycle in cyanobacteria".Science.334(6062): 1551–1553.Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1551Z.doi:10.1126/science.1210858.PMID22174252.S2CID206536295.

- ^Xiong W, Lee TC, Rommelfanger S, Gjersing E, Cano M, Maness PC, et al. (December 2015). "Phosphoketolase pathway contributes to carbon metabolism in cyanobacteria".Nature Plants.2(1): 15187.doi:10.1038/nplants.2015.187.PMID27250745.S2CID40094360.

- ^Smith A (1973)."Synthesis of metabolic intermediates".In Carr NG, Whitton BA (eds.).The Biology of Blue-green Algae.University of California Press. pp.30–.ISBN978-0-520-02344-4.

- ^Jangoux M (1987)."Diseases of Echinodermata. I. Agents microorganisms and protistans".Diseases of Aquatic Organisms.2:147–62.doi:10.3354/dao002147.

- ^Kinne O, ed. (1980).Diseases of Marine Animals(PDF).Vol. 1. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-0-471-99584-5.

- ^Kristiansen A (1964)."Sarcinastrum urosporae,a Colourless Parasitic Blue-green Alga "(PDF).Phycologia.4(1): 19–22.Bibcode:1964Phyco...4...19K.doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-4-1-19.1.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 January 2015.

- ^Mazard S, Penesyan A, Ostrowski M, Paulsen IT, Egan S (May 2016)."Tiny Microbes with a Big Impact: The Role of Cyanobacteria and Their Metabolites in Shaping Our Future".Marine Drugs.14(5): 97.doi:10.3390/md14050097.PMC4882571.PMID27196915.

- ^de los Ríos A, Grube M, Sancho LG, Ascaso C (February 2007)."Ultrastructural and genetic characteristics of endolithic cyanobacterial biofilms colonizing Antarctic granite rocks".FEMS Microbiology Ecology.59(2): 386–395.Bibcode:2007FEMME..59..386D.doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00256.x.PMID17328119.

- ^Vaughan T (2011).Mammalogy.Jones and Barlett. p. 21.ISBN978-0763762995.

- ^Schultz N (30 August 2009)."Photosynthetic viruses keep world's oxygen levels up".New Scientist.

- ^abcJöhnk KD, Huisman J, Sharples J, Sommeijer B, Visser PM, Stroom JM (1 March 2008)."Summer heatwaves promote blooms of harmful cyanobacteria".Global Change Biology.14(3): 495–512.Bibcode:2008GCBio..14..495J.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01510.x.S2CID54079634.

- ^"Linda Lawton – 11th International Conference on Toxic Cyanobacteria".Retrieved25 June2021.

- ^Paerl HW, Paul VJ (April 2012). "Climate change: links to global expansion of harmful cyanobacteria".Water Research.46(5): 1349–1363.Bibcode:2012WatRe..46.1349P.doi:10.1016/j.watres.2011.08.002.PMID21893330.

- ^Thomas AD, Dougill AJ (15 March 2007). "Spatial and temporal distribution of cyanobacterial soil crusts in the Kalahari: Implications for soil surface properties".Geomorphology.85(1): 17–29.Bibcode:2007Geomo..85...17T.doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.03.029.

- ^Belnap J, Gardner JS (1993). "Soil Microstructure in Soils of the Colorado Plateau: The Role of the Cyanobacterium Microcoleus Vaginatus".The Great Basin Naturalist.53(1): 40–47.JSTOR41712756.