Czech language

| Czech | |

|---|---|

| čeština,český jazyk | |

| Native to | Czech Republic |

| Ethnicity | Czechs |

Native speakers | 10.6 million (2015)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Institute of the Czech Language (of theAcademy of Sciences of the Czech Republic) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | cs |

| ISO 639-2 | cze(B)ces(T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ces |

| Glottolog | czec1258 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-da <53-AAA-b...-d |

| IETF | cs[4] |

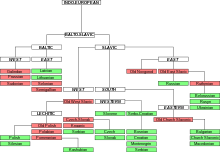

Czech(/tʃɛk/CHEK;endonym:čeština[ˈtʃɛʃcɪna]), historically also known asBohemian[5](/boʊˈhiːmiən,bə-/boh-HEE-mee-ən, bə-;[6]Latin:lingua Bohemica), is aWest Slavic languageof theCzech–Slovak group,written inLatin script.[5]Spoken by over 10 million people, it serves as the official language of theCzech Republic.Czech is closely related toSlovak,to the point of highmutual intelligibility,as well as toPolishto a lesser degree.[7]Czech is afusional languagewith a rich system ofmorphologyand relatively flexibleword order.Its vocabulary has been extensively influenced byLatinandGerman.

The Czech–Slovak group developed within West Slavic in thehigh medievalperiod, and the standardization of Czech and Slovak within the Czech–Slovak dialect continuum emerged in the early modern period. In the later 18th to mid-19th century, the modern written standard became codified in the context of theCzech National Revival.The most widely spokennon-standard variety,known as Common Czech, is based on thevernacularofPrague,but is now spoken as aninterdialectthroughout most ofBohemia.TheMoravian dialectsspoken inMoraviaandCzech Silesiaare considerably more varied than the dialects of Bohemia.[8]

Czech has a moderately-sized phoneme inventory, comprising tenmonophthongs,threediphthongsand 25 consonants (divided into "hard", "neutral" and "soft" categories). Words may contain complicated consonant clusters or lack vowels altogether. Czech has araised alveolar trill,which is known to occur as aphonemein only a few other languages, represented by thegraphemeř.

Classification[edit]

Czech is a member of theWest Slavicsub-branch of theSlavicbranch of theIndo-Europeanlanguage family. This branch includesPolish,Kashubian,UpperandLower SorbianandSlovak.Slovak is the most closely related language to Czech, followed by Polish andSilesian.[9]

The West Slavic languages are spoken in Central Europe. Czech is distinguished from other West Slavic languages by a more-restricted distinction between "hard" and "soft" consonants (seePhonologybelow).[9]

History[edit]

Medieval/Old Czech[edit]

The term "Old Czech" is applied to the period predating the 16th century, with the earliest records of the high medieval period also classified as "early Old Czech", but the term "Medieval Czech" is also used. The function of the written language was initially performed byOld Slavonicwritten inGlagolitic,later byLatinwritten inLatin script.

Around the 7th century, theSlavic expansionreached Central Europe, settling on the eastern fringes of theFrankish Empire.The West Slavic polity ofGreat Moraviaformed by the 9th century. TheChristianization of Bohemiatook place during the 9th and 10th centuries. The diversification of theCzech-Slovakgroup withinWest Slavicbegan around that time, marked among other things by its use of thevoiced velar fricativeconsonant (/ɣ/)[10]and consistent stress on the first syllable.[11]

The Bohemian (Czech) language is first recorded in writing in glosses and short notes during the 12th to 13th centuries. Literary works written in Czech appear in the late 13th and early 14th century and administrative documents first appear towards the late 14th century. The first completeBible translation,theLeskovec-Dresden Bible,also dates to this period.[12]Old Czech texts, including poetry and cookbooks, were also produced outside universities.[13]

Literary activity becomes widespread in the early 15th century in the context of theBohemian Reformation.Jan Huscontributed significantly to the standardization ofCzech orthography,advocated for widespread literacy among Czech commoners (particularly in religion) and made early efforts to model written Czech after the spoken language.[12]

Early Modern Czech[edit]

There was no standardization distinguishing between Czech and Slovak prior to the 15th century. In the 16th century, the division between Czech and Slovak becomes apparent, marking the confessional division between Lutheran Protestants in Slovakia using Czech orthography and Catholics, especially Slovak Jesuits, beginning to use a separate Slovak orthography based on Western Slovak dialects.[14][15]

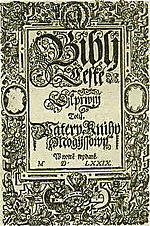

The publication of theKralice Biblebetween 1579 and 1593 (the first complete Czech translation of the Bible from the original languages) became very important for standardization of the Czech language in the following centuries as it was used as a model for the standard language.[16]

In 1615, the Bohemiandiettried to declare Czech to be the only official language of the kingdom. After theBohemian Revolt(of predominantly Protestant aristocracy) which was defeated by theHabsburgsin 1620, the Protestant intellectuals had to leave the country. This emigration together with other consequences of theThirty Years' Warhad a negative impact on the further use of the Czech language. In 1627, Czech and German became official languages of the Kingdom of Bohemia and in the 18th century German became dominant in Bohemia and Moravia, especially among the upper classes.[17]

Modern Czech[edit]

The modern standard Czech language originates in standardization efforts of the 18th century.[18]By then the language had developed a literary tradition, and since then it has changed little; journals from that period have no substantial differences from modern standard Czech, and contemporary Czechs can understand them with little difficulty.[19]Sometime before the 18th century, the Czech language abandoned a distinction between phonemic /l/ and /ʎ/ which survives in Slovak.[20]

With the beginning of the national revival of the mid-18th century, Czech historians began to emphasize their people's accomplishments from the 15th through the 17th centuries, rebelling against theCounter-Reformation(the Habsburg re-catholization efforts which had denigrated Czech and other non-Latinlanguages).[21]Czechphilologistsstudied sixteenth-century texts, advocating the return of the language tohigh culture.[22]This period is known as the Czech National Revival[23](or Renaissance).[22]

During the national revival, in 1809 linguist and historianJosef Dobrovskýreleased a German-language grammar of Old Czech entitledAusführliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprache('Comprehensive Doctrine of the Bohemian Language'). Dobrovský had intended his book to bedescriptive,and did not think Czech had a realistic chance of returning as a major language. However,Josef Jungmannand other revivalists used Dobrovský's book to advocate for a Czech linguistic revival.[23]Changes during this time included spelling reform (notably,íin place of the formerjandjin place ofg), the use oft(rather thanti) to end infinitive verbs and the non-capitalization of nouns (which had been a late borrowing from German).[20]These changes differentiated Czech from Slovak.[24]Modern scholars disagree about whether the conservative revivalists were motivated by nationalism or considered contemporary spoken Czech unsuitable for formal, widespread use.[23]

Adherence to historical patterns was later relaxed and standard Czech adopted a number of features from Common Czech (a widespread, informally used interdialectal variety), such as leaving some proper nouns undeclined. This has resulted in a relatively high level of homogeneity among all varieties of the language.[25]

Geographic distribution[edit]

Czech is spoken by about 10 million residents of theCzech Republic.[17][26]AEurobarometersurvey conducted from January to March 2012 found that thefirst languageof 98 percent of Czech citizens was Czech, the third-highest proportion of a population in theEuropean Union(behindGreeceandHungary).[27]

As the official language of the Czech Republic (a member of theEuropean Unionsince 2004), Czech is one of the EU's official languages and the 2012 Eurobarometer survey found that Czech was the foreign language most often used in Slovakia.[27]Economist Jonathan van Parys collected data on language knowledge in Europe for the 2012European Day of Languages.The five countries with the greatest use of Czech were theCzech Republic(98.77 percent),Slovakia(24.86 percent),Portugal(1.93 percent),Poland(0.98 percent) andGermany(0.47 percent).[28]

Czech speakers in Slovakia primarily live in cities. Since it is a recognizedminority languagein Slovakia, Slovak citizens who speak only Czech may communicate with the government in their language to the extent that Slovak speakers in the Czech Republic may do so.[29]

United States[edit]

Immigration of Czechs from Europe to the United States occurred primarily from 1848 to 1914. Czech is aLess Commonly Taught Languagein U.S. schools, and is taught at Czech heritage centers. Large communities ofCzech Americanslive in the states ofTexas,NebraskaandWisconsin.[30]In the2000 United States Census,Czech was reported as the commonestlanguage spoken at home(besidesEnglish) inValley,ButlerandSaundersCounties,Nebraska andRepublic County, Kansas.With the exception ofSpanish(the non-English language most commonly spoken at home nationwide), Czech was the most common home language in more than a dozen additional counties in Nebraska, Kansas, Texas,North DakotaandMinnesota.[31]As of 2009,[update]70,500 Americans spoke Czech as their first language (49th place nationwide, afterTurkishand beforeSwedish).[32]

Phonology[edit]

Vowels[edit]

Standard Czech contains ten basicvowelphonemes,and three diphthongs. The vowels are/a/,/ɛ/,/ɪ/,/o/,and/u/,and their long counterparts/aː/,/ɛː/,/iː/,/oː/and/uː/.The diphthongs are/ou̯/,/au̯/and/ɛu̯/;the last two are found only in loanwords such asauto"car" andeuro"euro".[33]

In Czech orthography, the vowels are spelled as follows:

- Short:a, e/ě, i/y, o, u

- Long:á, é, í/ý, ó, ú/ů

- Diphthongs:ou, au, eu

The letter⟨ě⟩indicates that the previous consonant is palatalized (e.g.něco/ɲɛt͡so/). After a labial it represents/jɛ/(e.g.běs/bjɛs/); but⟨mě⟩is pronounced /mɲɛ/, cf.měkký(/mɲɛkiː/).[34]

Consonants[edit]

The consonant phonemes of Czech and their equivalent letters in Czech orthography are as follows:[35]

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m⟨m⟩ | n⟨n⟩ | ɲ⟨ň⟩ | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p⟨p⟩ | t⟨t⟩ | c⟨ť⟩ | k⟨k⟩ | ||

| voiced | b⟨b⟩ | d⟨d⟩ | ɟ⟨ď⟩ | (ɡ)⟨g⟩ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s⟨c⟩ | t͡ʃ⟨č⟩ | ||||

| voiced | (d͡z) | (d͡ʒ) | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f⟨f⟩ | s⟨s⟩ | ʃ⟨š⟩ | x⟨ch⟩ | ||

| voiced | v⟨v⟩ | z⟨z⟩ | ʒ⟨ž⟩ | ɦ⟨h⟩ | |||

| Trill | plain | r⟨r⟩ | |||||

| fricative | r̝⟨ř⟩ | ||||||

| Approximant | l⟨l⟩ | j⟨j⟩ | |||||

Czech consonants are categorized as "hard", "neutral", or "soft":

- Hard:/d/,/ɡ/,/ɦ/,/k/,/n/,/r/,/t/,/x/

- Neutral:/b/,/f/,/l/,/m/,/p/,/s/,/v/,/z/

- Soft:/c/,/ɟ/,/j/,/ɲ/,/r̝/,/ʃ/,/t͡s/,/t͡ʃ/,/ʒ/

Hard consonants may not be followed byioríin writing, or soft ones byyorý(except in loanwords such askilogram).[36]Neutral consonants may take either character. Hard consonants are sometimes known as "strong", and soft ones as "weak".[37]This distinction is also relevant to thedeclensionpatterns of nouns, which vary according to whether the final consonant of the noun stem is hard or soft.[38]

Voicedconsonantswith unvoiced counterparts are unvoiced at the end of a word before a pause, and inconsonant clustersvoicing assimilationoccurs, which matches voicing to the following consonant. The unvoiced counterpart of /ɦ/ is /x/.[39]

The phoneme represented by the letterř(capitalŘ) is very rare among languages and often claimed to be unique to Czech, though it also occurs in some dialects ofKashubian,and formerly occurred in Polish.[40]It represents theraised alveolar non-sonorant trill(IPA:[r̝]), a sound somewhere between Czechrandž(example:),[41]and is present inDvořák.In unvoiced environments, /r̝/ is realized as its voiceless allophone [r̝̊], a sound somewhere between Czechrandš.[42]

The consonants/r/,/l/,and/m/can besyllabic,acting assyllable nucleiin place of a vowel.Strč prst skrz krk( "Stick [your] finger through [your] throat" ) is a well-known Czechtongue twisterusing syllabic consonants but no vowels.[43]

Stress[edit]

Each word has primarystresson its firstsyllable,except forenclitics(minor, monosyllabic, unstressed syllables). In all words of more than two syllables, every odd-numbered syllable receives secondary stress. Stress is unrelated to vowel length; both long and short vowels can be stressed or unstressed.[44]Vowels are never reduced in tone (e.g. toschwasounds) when unstressed.[45]When a noun is preceded by a monosyllabic preposition, the stress usually moves to the preposition, e.g.doPrahy"to Prague".[46]

Grammar[edit]

Czech grammar, like that of other Slavic languages, isfusional;its nouns, verbs, and adjectives areinflectedby phonological processes to modify their meanings and grammatical functions, and the easily separableaffixescharacteristic ofagglutinativelanguages are limited.[47] Czech inflects for case, gender and number in nouns and tense, aspect,mood,person and subject number and gender in verbs.[48]

Parts of speech include adjectives,adverbs,numbers,interrogative words,prepositions,conjunctionsandinterjections.[49]Adverbs are primarily formed from adjectives by taking the finalýoríof the base form and replacing it withe,ě,y,oro.[50]Negative statements are formed by adding the affixne-to the main verb of a clause,[51]with one exception:je(he, she or it is) becomesnení.[52]

Sentence and clause structure[edit]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | já | my |

| 2. | ty vy(formal) |

vy |

| 3. | on(masculine) ona(feminine) ono(neuter) |

oni(masculine animate) ony(masculine inanimate, feminine) ona(neuter) |

Because Czech usesgrammatical caseto convey word function in a sentence (instead of relying onword order,as English does), its word order is flexible. As apro-drop language,in Czech anintransitivesentence can consist of only a verb; information about its subject is encoded in the verb.[53]Enclitics (primarilyauxiliary verbsand pronouns) appear in the second syntactic slot of a sentence, after the first stressed unit. The first slot can contain a subject or object, a main form of a verb, an adverb, or a conjunction (except for the light conjunctionsa,"and",i,"and even" orale,"but" ).[54]

Czech syntax has asubject–verb–objectsentence structure. In practice, however, word order is flexible and used to distinguishtopic and focus,with the topic or theme (known referents) preceding the focus or rheme (new information) in a sentence; Czech has therefore been described as atopic-prominent language.[55]Although Czech has aperiphrasticpassiveconstruction (like English), in colloquial style, word-order changes frequently replace the passive voice. For example, to change "Peter killed Paul" to "Paul was killed by Peter" the order of subject and object is inverted:Petr zabil Pavla( "Peter killed Paul" ) becomes "Paul, Peter killed" (Pavla zabil Petr).Pavlais in theaccusative case,the grammatical object of the verb.[56]

A word at the end of a clause is typically emphasized, unless an upwardintonationindicates that the sentence is a question:[57]

- Pes jí bagetu.– The dog eats the baguette (rather than eating something else).

- Bagetu jí pes.– The dog eats the baguette (rather than someone else doing so).

- Pes bagetu jí.– The dog eats the baguette (rather than doing something else to it).

- Jí pes bagetu?– Does the dog eat the baguette? (emphasis ambiguous)

In parts ofBohemia(includingPrague), questions such asJí pes bagetu?without an interrogative word (such asco,"what" orkdo,"who" ) areintonedin a slow rise from low to high, quickly dropping to low on the last word or phrase.[58]

In modern Czech syntax, adjectives precede nouns,[59]with few exceptions.[60]Relative clausesare introduced byrelativizerssuch as the adjectivekterý,analogous to the Englishrelative pronouns"which", "that" and "who" / "whom". As with other adjectives, itagreeswith its associated noun in gender, number and case. Relative clauses follow the noun they modify. The following is aglossedexample:[61]

Chc-i

want-1SG

navštív-it

visit-INF

universit-u,

university-SG.ACC,

na

on

kter-ou

which-SG.F.ACC

chod-í

attend-3SG

Jan.

John.SG.NOM

I want to visit the university that John attends.

Declension[edit]

In Czech, nouns and adjectives are declined into one of sevengrammatical caseswhich indicate their function in a sentence, twonumbers(singular and plural) and threegenders(masculine, feminine and neuter). The masculine gender is further divided intoanimate and inanimateclasses.

Case[edit]

Anominative–accusative language,Czech marks subject nouns of transitive and intransitive verbs in the nominative case, which is the form found in dictionaries, anddirect objectsof transitive verbs are declined in the accusative case.[62]The vocative case is used to address people.[63]The remaining cases (genitive, dative, locative and instrumental) indicate semantic relationships, such asnoun adjuncts(genitive),indirect objects(dative), or agents in passive constructions (instrumental).[64]Additionallyprepositionsand some verbs require their complements to be declined in a certain case.[62]The locative case is only used after prepositions.[65]An adjective's case agrees with that of the noun it modifies. When Czech children learn their language's declension patterns, the cases are referred to by number:[66]

| No. | Ordinal name (Czech) | Full name (Czech) | Case | Main usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | první pád | nominativ | nominative | Subjects |

| 2. | druhý pád | genitiv | genitive | Noun adjuncts, possession, prepositions of motion, time and location |

| 3. | třetí pád | dativ | dative | Indirect objects, prepositions of motion |

| 4. | čtvrtý pád | akuzativ | accusative | Direct objects, prepositions of motion and time |

| 5. | pátý pád | vokativ | vocative | Addressing someone |

| 6. | šestý pád | lokál | locative | Prepositions of location, time and topic |

| 7. | sedmý pád | instrumentál | instrumental | Passive agents, instruments, prepositions of location |

Some prepositions require the nouns they modify to take a particular case. The cases assigned by each preposition are based on the physical (or metaphorical) direction, or location, conveyed by it. For example,od(from, away from) andz(out of, off) assign the genitive case. Other prepositions take one of several cases, with their meaning dependent on the case;nameans "onto" or "for" with the accusative case, but "on" with the locative.[67]

This is a glossed example of a sentence using several cases:

Nes-l

carry-SG.M.PST

js-em

be-1.SG

krabic-i

box-SG.ACC

do

into

dom-u

house-SG.GEN

se

with

sv-ým

own-SG.INS

přítel-em.

friend-SG.INS

I carried the box into the house with my friend.

Gender[edit]

Czech distinguishes threegenders—masculine, feminine, and neuter—and the masculine gender is subdivided intoanimateand inanimate. With few exceptions, feminine nouns in the nominative case end in-a,-e,or a consonant; neuter nouns in-o,-e,or-í,and masculine nouns in a consonant.[68]Adjectives, participles, most pronouns, and the numbers "one" and "two" are marked for gender and agree with the gender of the noun they modify or refer to.[69]Past tense verbs are also marked for gender, agreeing with the gender of the subject, e.g.dělal(he did, or made);dělala(she did, or made) anddělalo(it did, or made).[70]Gender also plays a semantic role; most nouns that describe people and animals, including personal names, have separate masculine and feminine forms which are normally formed by adding a suffix to the stem, for exampleČech(Czech man) has the feminine formČeška(Czech woman).[71]

Nouns of different genders follow different declension patterns. Examples of declension patterns for noun phrases of various genders follow:

| Case | Noun/adjective | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big dog (m. anim. sg.) | Black backpack (m. inanim. sg.) | Small cat (f. sg.) | Hard wood (n. sg.) | |

| Nom. | velký pes (big dog) |

černý batoh (black backpack) |

malá kočka (small cat) |

tvrdé dřevo (hard wood) |

| Gen. | bez velkého psa (without the big dog) |

bez černého batohu (without the black backpack) |

bez malé kočky (without the small cat) |

bez tvrdého dřeva (without the hard wood) |

| Dat. | k velkému psovi (to the big dog) |

k černému batohu (to the black backpack) |

k malé kočce (to the small cat) |

ke tvrdému dřevu (to the hard wood) |

| Acc. | vidím velkého psa (I see the big dog) |

vidím černý batoh (I see the black backpack) |

vidím malou kočku (I see the small cat) |

vidím tvrdé dřevo (I see the hard wood) |

| Voc. | velký pse! (big dog!) |

černý batohu! (black backpack!) |

malá kočko! (small cat!) |

tvrdé dřevo! (hard wood!) |

| Loc. | o velkém psovi (about the big dog) |

o černém batohu (about the black backpack) |

o malé kočce (about the small cat) |

o tvrdém dřevě (about the hard wood) |

| Inst. | s velkým psem (with the big dog) |

s černým batohem (with the black backpack) |

s malou kočkou (with the small cat) |

s tvrdým dřevem (with the hard wood) |

Number[edit]

Nouns are also inflected fornumber,distinguishing between singular and plural. Typical of a Slavic language, Czech cardinal numbers one through four allow the nouns and adjectives they modify to take any case, but numbers over five require subject and direct object noun phrases to be declined in the genitive plural instead of the nominative or accusative, and when used as subjects these phrases take singular verbs. For example:[72]

| English | Czech |

|---|---|

| one Czech crown was... | jedna koruna česká byla... |

| two Czech crowns were... | dvě koruny české byly... |

| three Czech crowns were... | tři koruny české byly... |

| four Czech crowns were... | čtyři koruny české byly... |

| five Czech crowns were... | pět korun českých bylo... |

Numbers decline for case, and the numbers one and two are also inflected for gender. Numbers one through five are shown below as examples. The number one has declension patterns identical to those of thedemonstrative pronounten.[73][74]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | jeden(masc) jedna(fem) jedno(neut) |

dva(masc) dvě(fem, neut) |

tři | čtyři | pět |

| Genitive | jednoho(masc) jedné(fem) jednoho(neut) |

dvou | tříortřech | čtyřorčtyřech | pěti |

| Dative | jednomu(masc) jedné(fem) jednomu(neut) |

dvěma | třem | čtyřem | pěti |

| Accusative | jednoho(masc an.) jeden(masc in.) jednu(fem) jedno(neut) |

dva(masc) dvě(fem, neut) |

tři | čtyři | pět |

| Locative | jednom(masc) jedné(fem) jednom(neut) |

dvou | třech | čtyřech | pěti |

| Instrumental | jedním(masc) jednou(fem) jedním(neut) |

dvěma | třemi | čtyřmi | pěti |

Although Czech'sgrammatical numbersare singular andplural,several residuals ofdualforms remain, such as the wordsdva( "two" ) andoba( "both" ), which decline the same way. Some nouns for paired body parts use a historical dual form to express plural in some cases:ruka(hand)—ruce(nominative);noha(leg)—nohama(instrumental),nohou(genitive/locative);oko(eye)—oči,anducho(ear)—uši.While two of these nouns are neuter in their singular forms, all plural forms are considered feminine; their gender is relevant to their associated adjectives and verbs.[75]These forms are plural semantically, used for any non-singular count, as inmezi čtyřma očima(face to face, lit.among four eyes). The plural number paradigms of these nouns are a mixture of historical dual and plural forms. For example,nohy(legs; nominative/accusative) is a standard plural form of this type of noun.[76]

Verb conjugation[edit]

Czech verbs agree with their subjects inperson(first, second or third),number(singular or plural), and in constructions involvingparticiples,which includes the past tense, also ingender.They are conjugated for tense (past, present orfuture) and mood (indicative,imperativeorconditional). For example, the conjugated verbmluvíme(we speak) is in the present tense and first-person plural; it is distinguished from other conjugations of theinfinitivemluvitby its ending,-íme.[77]The infinitive form of Czech verbs ends in-t(archaically,-tior-ci). It is the form found in dictionaries and the form that follows auxiliary verbs (for example,můžu tě slyšet— "I canhearyou ").[78]

Aspect[edit]

Typical of Slavic languages, Czech marks its verbs for one of twogrammatical aspects:perfectiveandimperfective.Most verbs are part of inflected aspect pairs—for example,koupit(perfective) andkupovat(imperfective). Although the verbs' meaning is similar, in perfective verbs the action is completed and in imperfective verbs it is ongoing or repeated. This is distinct frompastandpresent tense.[79]Any verb of either aspect can be conjugated into either the past or present tense,[77]but the future tense is only used with imperfective verbs.[80]Aspect describes the state of the action at the time specified by the tense.[79]

The verbs of most aspect pairs differ in one of two ways: by prefix or by suffix. In prefix pairs, the perfective verb has an added prefix—for example, the imperfectivepsát(to write, to be writing) compared with the perfectivenapsat(to write down). The most common prefixes arena-,o-,po-,s-,u-,vy-,z-andza-.[81]In suffix pairs, a different infinitive ending is added to the perfective stem; for example, the perfective verbskoupit(to buy) andprodat(to sell) have the imperfective formskupovatandprodávat.[82]Imperfective verbs may undergo further morphology to make other imperfective verbs (iterative andfrequentativeforms), denoting repeated or regular action. The verbjít(to go) has the iterative formchodit(to go regularly) and the frequentative formchodívat(to go occasionally; to tend to go).[83]

Many verbs have only one aspect, and verbs describing continual states of being—být(to be),chtít(to want),moct(to be able to),ležet(to lie down, to be lying down)—have no perfective form. Conversely, verbs describing immediate states of change—for example,otěhotnět(to become pregnant) andnadchnout se(to become enthusiastic)—have no imperfective aspect.[84]

Tense[edit]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | budu | budeme |

| 2. | budeš | budete |

| 3. | bude | budou |

The present tense in Czech is formed by adding an ending that agrees with the person and number of the subject at the end of the verb stem. As Czech is anull-subject language,the subject pronoun can be omitted unless it is needed for clarity.[85]The past tense is formed using aparticiplewhich ends in-land a further ending which agrees with the gender and number of the subject. For the first and second persons, the auxiliary verbbýtconjugated in the present tense is added.[86]

In some contexts, the present tense of perfective verbs (which differs from the Englishpresent perfect) implies future action; in others, it connotes habitual action.[87]The perfective present is used to refer to completion of actions in the future and is distinguished from the imperfective future tense, which refers to actions that will be ongoing in the future. The future tense is regularly formed using the future conjugation ofbýt(as shown in the table on the left) and the infinitive of an imperfective verb, for example,budu jíst— "I will eat" or "I will be eating".[80]Wherebuduhas a noun or adjective complement it means "I will be", for example,budu šťastný(I will be happy).[80]Some verbs of movement form their future tense by adding the prefixpo-to the present tense forms instead, e.g.jedu( "I go" ) >pojedu( "I will go" ).[88]

Mood[edit]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | koupil/a bych | koupili/y bychom |

| 2. | koupil/a bys | koupili/y byste |

| 3. | koupil/a/o by | koupili/y/a by |

Czech verbs have threegrammatical moods:indicative,imperativeandconditional.[89]The imperative mood is formed by adding specific endings for each of three person–number categories:-Ø/-i/-ejfor second-person singular,-te/-ete/-ejtefor second-person plural and-me/-eme/-ejmefor first-person plural.[90]Imperatives are usually expressed using perfective verbs if positive and imperfective verbs if negative.[91]The conditional mood is formed with a conditionalauxiliary verbafter the participle ending in -l which is used to form the past tense. This mood indicates hypothetical events and can also be used to express wishes.[92]

Verb classes[edit]

Most Czech verbs fall into one of fiveclasses,which determine their conjugation patterns. The future tense ofbýtwould be classified as a Class I verb because of its endings. Examples of the present tense of each class and some common irregular verbs follow in the tables below:[93]

|

|

Orthography[edit]

Czech has one of the mostphonemic orthographiesof all European languages. Its Alpha bet contains 42graphemes,most of which correspond to individualphonemes,[94]and only contains only onedigraph:ch,which followshin the Alpha bet.[95]The charactersq,wandxappear only in foreign words.[96]Theháček(ˇ) is used with certain letters to form new characters:š,ž,andč,as well asň,ě,ř,ť,andď(the latter five uncommon outside Czech). The last two letters are sometimes written with a comma above (ʼ, an abbreviated háček) because of their height.[97]Czech orthography has influenced the orthographies of other Balto-Slavic languages and some of its characters have been adopted fortransliteration of Cyrillic.[98]

Czech orthography reflectsvowel length;long vowels are indicated by anacute accentor, in the case of the characterů,aring.Longuis usually writtenúat the beginning of a word or morpheme (úroda,neúrodný) andůelsewhere,[99]except for loanwords (skútr) or onomatopoeia (bú).[100]Long vowels anděare not considered separate letters in the Alpha betical order.[101]The characteróexists only in loanwords andonomatopoeia.[102]

Czechtypographicalfeatures not associated with phonetics generally resemble those of most European languages that use theLatin script,including English.Proper nouns,honorifics,and the first letters of quotations arecapitalized,andpunctuationis typical of other Latin European languages. Ordinal numbers (1st) use a point, as in German (1.). The Czech language uses a decimal comma instead of a decimal point. When writing a long number, spaces between every three digits, including those in decimal places, may be used for better orientation in handwritten texts. The number 1,234,567.89101 may be written as 1234567,89101 or 1 234 567,891 01.[103]Inproper nounphrases (except personal and settlement names), only the first word and proper nouns inside such phrases are capitalized (Pražský hrad,Prague Castle).[104][105]

Varieties[edit]

The modern literary standard and prestige variety, known as "Standard Czech" (spisovná čeština) is based on the standardization during theCzech National Revivalin the 1830s, significantly influenced byJosef Jungmann's Czech–German dictionary published during 1834–1839. Jungmann used vocabulary of theBible of Kralice(1579–1613) period and of the language used by his contemporaries. He borrowed words not present in Czech from other Slavic languages or created neologisms.[106]Standard Czech is the formal register of the language which is used in official documents, formal literature, newspaper articles, education and occasionally public speeches.[107]It is codified by theCzech Language Institute,who publish occasional reforms to the codification. The most recent reform took place in 1993.[108]The termhovorová čeština(lit. "Colloquial Czech" ) is sometimes used to refer to the spoken variety of standard Czech.[109]

The most widely spoken vernacular form of the language is called "Common Czech" (obecná čeština), aninterdialectinfluenced by spoken Standard Czech and the Central Bohemian dialects of thePragueregion. Other Bohemian regional dialects have become marginalized, whileMoravian dialectsremain more widespread and diverse, with a political movement for Moravian linguistic revival active since the 1990s.

These varieties of the language (Standard Czech, spoken/colloquial Standard Czech, Common Czech, and regional dialects) form astylistic continuum,in which contact between varieties of a similar prestige influences change within them.[110]

Common Czech[edit]

The main Czech vernacular, spoken primarily inBohemiaincluding the capitalPrague,is known as Common Czech (obecná čeština). This is an academic distinction; most Czechs are unaware of the term or associate it with deformed or "incorrect" Czech.[111]Compared to Standard Czech, Common Czech is characterized by simpler inflection patterns and differences in sound distribution.[112]

Common Czech is distinguished from spoken/colloquial Standard Czech (hovorová čeština), which is astylistic varietywithin standard Czech.[113][114]Tomasz Kamuselladefines the spoken variety of Standard Czech as a compromise between Common Czech and the written standard,[115]whileMiroslav Komárekcalls Common Czech an intersection of spoken Standard Czech and regional dialects.[116]

Common Czech has become ubiquitous in most parts of the Czech Republic since the later 20th century. It is usually defined as aninterdialectused in common speech inBohemiaand western parts ofMoravia(by about two thirds of all inhabitants of theCzech Republic). Common Czech is notcodified,but some of its elements have become adopted in the written standard. Since the second half of the 20th century, Common Czech elements have also been spreading to regions previously unaffected, as a consequence of media influence. Standard Czech is still the norm for politicians, businesspeople and other Czechs in formal situations, but Common Czech is gaining ground in journalism and the mass media.[112]The colloquial form of Standard Czech finds limited use in daily communication due to the expansion of the Common Czech interdialect.[113]It is sometimes defined as a theoretical construct rather than an actual tool of colloquial communication, since in casual contexts, the non-standard interdialect is preferred.[113]

Common Czechphonologyis based on that of the Central Bohemian dialect group, which has a slightly different set of vowel phonemes to Standard Czech.[116]The phoneme /ɛː/ is peripheral and usually merges with /iː/, e.g. inmalýměsto(small town),plamínek(little flame) andlítat(to fly), and a second native diphthong /ɛɪ̯/ occurs, usually in places where Standard Czech has /iː/, e.g.malejdům(small house),mlejn(mill),plejtvat(to waste),bejt(to be).[117]In addition, a protheticv-is added to most words beginningo-,such asvotevřítvokno(to open the window).[118]

Non-standardmorphologicalfeatures that are more or less common among all Common Czech speakers include:[118]

- unifiedpluralendingsofadjectives:malýlidi(small people),malýženy(small women),malýměsta(small towns) – standard:malí lidé, malé ženy, malá města;

- unifiedinstrumentalending-mainplural:s těmadobrejmalidma,ženama,chlapama,městama(with the good people, women, guys, towns) – standard:s těmi dobrými lidmi, ženami, chlapy, městy.In essence, this form resembles the form of thedual,which was once a productive form, but now is almost extinct and retained in a lexically specific set of words. In Common Czech the ending became productive again around the 17th century, but used as a substitute for a regular plural form.[119]

- omission of the syllabic-lin the masculine ending of past tense verbs:řek(he said),moh(he could),pích(he pricked) – standard:řekl, mohl, píchl.

- tendency of merging the locative singular masculine/neuter for adjectives with the instrumental by changing the locative ending-émto-ýmand then shortening the vowel:mladém(standard locative),mladým(standard instrumental) >mladým(Common Czech locative),mladym(Common Czech instrumental) >mladym(Common Czech locative/instrumental with shortening).[120]

Examples of declension (Standard Czech is added in italics for comparison):

| Masculine animate |

Masculine inanimate |

Feminine | Neuter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg. | Nominative | mladejčlověk mladý člověk |

mladejstát mladý stát |

mladá žena mladá žena |

mladýzvíře mladé zvíře |

| Genitive | mladýhočlověka mladého člověka |

mladýhostátu mladého státu |

mladýženy mladé ženy |

mladýhozvířete mladého zvířete | |

| Dative | mladýmučlověkovi mladému člověku |

mladýmustátu mladému státu |

mladýženě mladé ženě |

mladýmuzvířeti mladému zvířeti | |

| Accusative | mladýhočlověka mladého člověka |

mladejstát mladý stát |

mladou ženu mladou ženu |

mladýzvíře mladé zvíře | |

| Vocative | mladejčlověče! mladý člověče! |

mladejstáte! mladý státe! |

mladá ženo! mladá ženo! |

mladýzvíře! mladé zvíře! | |

| Locative | mladýmčlověkovi mladém člověkovi |

mladýmstátě mladém státě |

mladýženě mladé ženě |

mladýmzvířeti mladém zvířeti | |

| Instrumental | mladymčlověkem mladým člověkem |

mladymstátem mladým státem |

mladou ženou mladou ženou |

mladymzvířetem mladým zvířetem | |

| Pl. | Nominative | mladýlidi mladí lidé |

mladýstáty mladé státy |

mladýženy mladé ženy |

mladýzvířata mladá zvířata |

| Genitive | mladejchlidí mladých lidí |

mladejchstátů mladých států |

mladejchžen mladých žen |

mladejchzvířat mladých zvířat | |

| Dative | mladejmlidem mladým lidem |

mladejmstátům mladým státům |

mladejmženám mladým ženám |

mladejmzvířatům mladým zvířatům | |

| Accusative | mladýlidi mladé lidi |

mladýstáty mladé státy |

mladýženy mladé ženy |

mladýzvířata mladá zvířata | |

| Vocative | mladýlidi! mladí lidé! |

mladýstáty! mladé státy! |

mladýženy! mladé ženy! |

mladýzvířata! mladá zvířata! | |

| Locative | mladejchlidech mladých lidech |

mladejchstátech mladých státech |

mladejchženách mladých ženách |

mladejchzvířatech mladých zvířatech | |

| Instrumental | mladejmalidma mladými lidmi |

mladejmastátama mladými státy |

mladejmaženama mladými ženami |

mladejmazvířatama mladými zvířaty |

mladý člověk – young man/person, mladí lidé – young people, mladý stát – young state, mladá žena – young woman, mladé zvíře – young animal

Bohemian dialects[edit]

Apart from the Common Czech vernacular, there remain a variety of other Bohemian dialects, mostly in marginal rural areas. Dialect use began to weaken in the second half of the 20th century, and by the early 1990s regional dialect use was stigmatized, associated with the shrinking lower class and used in literature or other media for comedic effect. Increased travel and media availability to dialect-speaking populations has encouraged them to shift to (or add to their own dialect) Standard Czech.[121]

TheCzech Statistical Officein 2003 recognized the following Bohemian dialects:[122]

- Nářečí středočeská(Central Bohemian dialects)

- Nářečí jihozápadočeská(Southwestern Bohemian dialects)

- Nářečí severovýchodočeská(Northeastern Bohemian dialects)

- Podskupina podkrknošská(Krkonošesubgroup)

Moravian dialects[edit]

The Czech dialects spoken inMoraviaandSilesiaare known asMoravian(moravština). In theAustro-Hungarian Empire,"Bohemian-Moravian-Slovak" was a language citizens could register as speaking (with German, Polish and several others).[123]In the 2011 census, where respondents could optionally specify up to two first languages,[124]62,908 Czech citizens specified Moravian as their first language and 45,561 specified both Moravian and Czech.[125]

Beginning in the sixteenth century, some varieties of Czech resembled Slovak;[14]the southeastern Moravian dialects form a continuum between the Czech and Slovak languages,[126]using the same declension patterns for nouns and pronouns and the same verb conjugations as Slovak.[127]

A popular misconception holds that eastern Moravian dialects are closer to Slovak than Czech, but this is incorrect; in fact, the opposite is true, and certain dialects in far western Slovakia exhibit features more akin to standard Czech than to standard Slovak.[8]

TheCzech Statistical Officein 2003 recognized the following Moravian dialects:[122]

- Nářečí českomoravská(Bohemian–Moravian dialects)

- Nářečí středomoravská(Central Moravian dialects)

- Podskupina tišnovská(Tišnovsubgroup)

- Nářečí východomoravská(Eastern Moravian dialects)

- Podskupina slovácká(Moravian Slovaksubgroup)

- Podskupina valašská(Moravian Wallachiansubgroup)

- Nářečí slezská(Silesian dialects)

Sample[edit]

In a 1964 textbook on Czechdialectology,Břetislav Koudela used the following sentence to highlight phonetic differences between dialects:[128]

| Standard Czech: | Dejmoukuzemlýna na vozík. |

| Common Czech: | Dejmoukuzemlejna na vozejk. |

| Central Moravian: | Démókozemléna na vozék. |

| Eastern Moravian: | Dajmúkuzemłýna na vozík. |

| Silesian: | Dajmukuzemłyna na vozik. |

| Slovak: | Dajmúkuz mlyna na vozík. |

| English: | Put the flour from the mill into the cart. |

Mutual intelligibility with Slovak[edit]

Czech and Slovak have been consideredmutually intelligible;speakers of either language can communicate with greater ease than those of any other pair of West Slavic languages.[129]Following the 1993dissolution of Czechoslovakia,mutual intelligibility declined for younger speakers, probably because Czech speakers began to experience less exposure to Slovak and vice versa.[130]A 2015 study involving participants with a mean age of around 23 nonetheless concluded that there remained a high degree of mutual intelligibility between the two languages.[129]Grammatically, both languages share a common syntax.[14]

One study showed that Czech and Slovaklexiconsdiffered by 80 percent, but this high percentage was found to stem primarily from differing orthographies and slight inconsistencies in morphological formation;[131]Slovak morphology is more regular (when changing from thenominativeto thelocative case,PrahabecomesPrazein Czech andPrahein Slovak). The two lexicons are generally considered similar, with most differences found in colloquial vocabulary and some scientific terminology. Slovak has slightly more borrowed words than Czech.[14]

The similarities between Czech and Slovak led to the languages being considered a single language by a group of 19th-century scholars who called themselves "Czechoslavs" (Čechoslované), believing that the peoples were connected in a way which excludedGerman Bohemiansand (to a lesser extent)Hungariansand other Slavs.[132]During theFirst Czechoslovak Republic(1918–1938), although "Czechoslovak" was designated as the republic's official language, both Czech and Slovak written standards were used. Standard written Slovak was partially modeled on literary Czech, and Czech was preferred for some official functions in the Slovak half of the republic. Czech influence on Slovak was protested by Slovak scholars, and when Slovakia broke off from Czechoslovakia in 1938 as theSlovak State(which then aligned withNazi GermanyinWorld War II), literary Slovak was deliberately distanced from Czech. When theAxis powerslost the war and Czechoslovakia reformed, Slovak developed somewhat on its own (with Czech influence); during thePrague Springof 1968, Slovak gained independence from (and equality with) Czech,[14]due to the transformation of Czechoslovakia from a unitary state to a federation. Since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, "Czechoslovak" has referred to improvisedpidginsof the languages which have arisen from the decrease in mutual intelligibility.[133]

Vocabulary[edit]

Czech vocabulary derives primarily from Slavic, Baltic and other Indo-European roots. Although most verbs have Balto-Slavic origins, pronouns, prepositions and some verbs have wider, Indo-European roots.[134]Some loanwords have been restructured byfolk etymologyto resemble native Czech words (e.g.hřbitov,"graveyard" andlistina,"list" ).[135]

Most Czech loanwords originated in one of two time periods. Earlier loanwords, primarily from German,[136]Greekand Latin,[137]arrived before the Czech National Revival. More recent loanwords derive primarily from English andFrench,[136]and also fromHebrew,ArabicandPersian.Many Russian loanwords, principally animal names and naval terms, also exist in Czech.[138]

Although older German loanwords were colloquial, recent borrowings from other languages are associated with high culture.[136]During the nineteenth century, words with Greek and Latin roots were rejected in favor of those based on older Czech words and common Slavic roots; "music" ismuzykain Polish andмузыка(muzyka) in Russian, but in Czech it ishudba.[137]Some Czech words have been borrowed as loanwords intoEnglishand other languages—for example,robot(fromrobota,"labor" )[139]andpolka(frompolka,"Polishwoman "or from" půlka "" half ").[140]

Example text[edit]

Article 1 of theUniversal Declaration of Human Rightsin Czech:

- Všichni lidé rodí se svobodní a sobě rovní co do důstojnosti a práv. Jsou nadáni rozumem a svědomím a mají spolu jednat v duchu bratrství.[141]

Article 1 of theUniversal Declaration of Human Rightsin English:

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[142]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^CzechatEthnologue(18th ed., 2015)(subscription required)

- ^abcde"Full list".Council of Europe.

- ^Ministry of Interior of Poland: Act of 6 January 2005 on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional languages

- ^IANA language subtag registry,retrieved October 15, 2018

- ^ab"Czech language".Encyclopædia Britannica.Retrieved6 January2015.

- ^Jones, Daniel(2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.),English Pronouncing Dictionary,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-3-12-539683-8

- ^Swan, Oscar E. (2002).A grammar of contemporary Polish.Bloomington, Ind.: Slavica. p. 5.ISBN0893572969.OCLC50064627.

- ^abRejzek, Jiří (2021).Zrození češtiny(in Czech). Prague: Univerzita Karlova, Filozofická fakulta. pp. 102, 130.ISBN978-80-7422-799-8.

- ^abSussex & Cubberley 2011,pp. 54–56

- ^Liberman & Trubetskoi 2001,p. 112

- ^Liberman & Trubetskoi 2001,p. 153

- ^abSussex & Cubberley 2011,pp. 98–99

- ^Piotrowski 2012,p. 95

- ^abcdeBerger, Tilman."Slovaks in Czechia – Czechs in Slovakia"(PDF).University of Tübingen.Retrieved2014-08-09.

- ^Kamusella, Tomasz (2008).The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe.Springer. pp. 134–135.

- ^Michálek, Emanuel."O jazyce Kralické bible".Naše řeč(in Czech). Czech Language Institute.Retrieved2021-11-02.

- ^abCerna & Machalek 2007,p. 26

- ^Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993,p. 92

- ^Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993,p. 95

- ^abMaxwell 2009,p. 106

- ^Agnew 1994,p. 250

- ^abAgnew 1994,pp. 251–252

- ^abcWilson 2009,p. 18

- ^Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993,p. 96

- ^Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993,pp. 93–95

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 2

- ^ab"Europeans and Their Languages"(PDF).Eurobarometer.June 2012.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2012-06-22.RetrievedJuly 25,2014.

- ^van Parys, Jonathan (2012)."Language knowledge in the European Union".Language Knowledge.RetrievedJuly 23,2014.

- ^Škrobák, Zdeněk."Language Policy of Slovak Republic"(PDF).Annual of Language & Politics and Politics of Identity. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on July 26, 2014.RetrievedJuly 26,2014.

- ^Hrouda, Simone J."Czech Language Programs and Czech as a Heritage Language in the United States"(PDF).University of California, Berkeley.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2013-03-02.RetrievedJuly 23,2014.

- ^"Chapter 8: Language"(PDF).Census.gov.2000.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2008-10-06.RetrievedJuly 23,2014.

- ^"Languages of the U.S.A"(PDF).U.S. English.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 20, 2009.RetrievedJuly 25,2014.

- ^Dankovičová 1999,p. 72

- ^Campbell, George L.; Gareth King (1984).Compendium of the world's languages.Routledge.

- ^Dankovičová 1999,pp. 70–72

- ^"Psaní i – y po písmenu c".Czech Language Institute.Retrieved11 August2014.

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 11

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 20–21

- ^Dankovičová 1999,p. 73

- ^Nichols, Joanna(2018). Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.).Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics.p. 1607.

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 6

- ^Dankovičová 1999,p. 71

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 5

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 12

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 9

- ^"Sound Patterns of Czech".Charles University Institute of Phonetics.Retrieved3 November2021.

- ^Qualls 2012,pp. 6–8

- ^Qualls 2012,p. 5

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. v–viii

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 61–63

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 212

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 134

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 74

- ^Short 2009,p. 324.

- ^Anderman, Gunilla M.; Rogers, Margaret (2008).Incorporating Corpora: The Linguist and the Translator.Multilingual Matters. pp. 135–136.

- ^Short 2009,p. 325.

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 10–11

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 10

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 48

- ^Uhlířová, Ludmila."SLOVOSLED NOMINÁLNÍ SKUPINY".Nový encyklopedický slovník češtiny.Retrieved2017-10-18.

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 271

- ^abNaughton 2005,p. 196

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 201

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 197–199

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 199

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 25

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 201–205

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 22–24

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 51

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 141

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 238

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 114

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 83

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 117

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 40

- ^Komárek 2012,p. 238

- ^abNaughton 2005,p. 131

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 7

- ^abNaughton 2005,p. 146

- ^abcNaughton 2005,p. 151

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 147

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 147–148

- ^Lukeš, Dominik (2001)."Gramatická terminologie ve vyučování – Terminologie a platonický svět gramatických idejí".DominikLukeš.net. Archived fromthe originalon September 23, 2011.RetrievedAugust 5,2014.

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 149

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 134

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 140–142

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 150

- ^Karlík, Petr; Migdalski, Krzysztof."FUTURUM (budoucí čas)".Nový encyklopedický slovník češtiny.Retrieved18 August2019.

- ^Rothstein & Thieroff 2010,p. 359

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 157

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 159

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 152–154

- ^Naughton 2005,pp. 136–140

- ^Neustupný, J.V.;Nekvápil, Jiří. Kaplan, Robert B.; Baldauf, Richard B. Jr. (eds.).Language Planning and Policy in Europe.pp. 78–79.

- ^Pansofia 1993,p. 11

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 1

- ^Harkins 1952,pp. 6–8

- ^Berger, Tilman. "Religion and diacritics: The case of Czech orthography". In Baddeley, Susan; Voeste, Anja (eds.).Orthographies in Early Modern Europe.p. 255.

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 7

- ^Pansofia 1993,p. 26

- ^Hajičová 1986,p. 31

- ^Harkins 1952,p. 8

- ^Členění čísel,Internetová jazyková příručka, ÚJČ AVČR

- ^Naughton 2005,p. 11

- ^Pansofia 1993,p. 34

- ^Naughton, James."CZECH LITERATURE, 1774 TO 1918".Oxford University. Archived fromthe originalon 12 June 2012.Retrieved25 October2012.

- ^Tahal 2010,p. 245

- ^Tahal 2010,p. 252

- ^Hoffmanová, Jana."HOVOROVÝ STYL".Nový encyklopedický slovník češtiny.Retrieved21 August2019.

- ^Koudela 1964,p. 136

- ^Wilson 2009,p. 21

- ^abDaneš, František (2003)."The present-day situation of Czech".Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic.RetrievedAugust 10,2014.

- ^abcBalowska, Grażyna (2006)."Problematyka czeszczyzny potocznej nieliterackiej (tzw. obecná čeština) na łamach czasopisma" Naše řeč "w latach dziewięćdziesiątych"(PDF).Bohemistyka(in Polish) (1). Opole.ISSN1642-9893.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2019-05-05.

- ^Štěpán, Josef (2015)."Hovorová spisovná čeština"(PDF).Bohemistyka(in Czech) (2). Prague.ISSN1642-9893.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2019-05-10.

- ^Kamusella, Tomasz (2008).The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe.Springer. p. 506.ISBN9780230583474.

- ^abKomárek 2012,p. 117

- ^Komárek 2012,p. 116

- ^abTahal 2010,pp. 245–253

- ^Komárek 2012,pp. 179–180

- ^Cummins, George M. (2005). "Literary Czech, Common Czech, and the Instrumental Plural".Journal of Slavic Linguistics.13(2). Slavica Publishers: 271–297.JSTOR24599659.

- ^Eckert 1993,pp. 143–144

- ^ab"Map of Czech Dialects".Český statistický úřad (Czech Statistical Office). 2003. Archived fromthe originalon December 1, 2012.RetrievedJuly 26,2014.

- ^Kortmann & van der Auwera 2011,p. 714

- ^Zvoníček, Jiří (30 March 2021)."Sčítání lidu a moravská národnost. Přihlásíte se k ní?".Kroměřížský Deník.Retrieved30 September2021.

- ^"Tab. 614b Obyvatelstvo podle věku, mateřského jazyka a pohlaví (Population by Age, Mother Tongue, and Gender)"(in Czech). Český statistický úřad (Czech Statistical Office). March 26, 2011.RetrievedJuly 26,2014.

- ^Kortmann & van der Auwera 2011,p. 516

- ^Šustek, Zbyšek (1998)."Otázka kodifikace spisovného moravského jazyka (The question of codifying a written Moravian language)"(in Czech).University of Tartu.RetrievedJuly 21,2014.

- ^Koudela 1964,p. 173

- ^abGolubović, Jelena; Gooskens, Charlotte (2015)."Mutual intelligibility between West and South Slavic languages".Russian Linguistics.39(3): 351–373.doi:10.1007/s11185-015-9150-9.

- ^Short 2009,p. 306.

- ^Esposito 2011,p. 82

- ^Maxwell 2009,pp. 101–105

- ^Nábělková, Mira (January 2007)."Closely-related languages in contact: Czech, Slovak," Czechoslovak "".International Journal of the Sociology of Language.RetrievedAugust 18,2014.

- ^Mann 1957,p. 159

- ^Mann 1957,p. 160

- ^abcMathesius 2013,p. 20

- ^abSussex & Cubberley 2011,p. 101

- ^Mann 1957,pp. 159–160

- ^Harper, Douglas."robot (n.)".Online Etymology Dictionary.RetrievedJuly 22,2014.

- ^Harper, Douglas."polka (n.)".Online Etymology Dictionary.RetrievedJuly 22,2014.

- ^"Universal Declaration of Human Rights".unicode.org.

- ^"Universal Declaration of Human Rights".un.org.

References[edit]

- Agnew, Hugh LeCaine (1994).Origins of the Czech National Renascence.University of PittsburghPress.ISBN978-0-8229-8549-5.

- Dankovičová, Jana (1999). "Czech".Handbook of the International Phonetic Association(9th ed.). International Phonetic Association/Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-63751-0.

- Cerna, Iva; Machalek, Jolana (2007).Beginner's Czech.Hippocrene Books.ISBN978-0-7818-1156-9.

- Chloupek, Jan; Nekvapil, Jiří (1993).Studies in Functional Stylistics.John Benjamins Publishing Company.ISBN978-90-272-1545-1.

- Eckert, Eva (1993).Varieties of Czech: Studies in Czech Sociolinguistics.Editions Rodopi.ISBN978-90-5183-490-1.

- Esposito, Anna (2011).Analysis of Verbal and Nonverbal Communication and Enactment: The Processing Issues.Springer Press.ISBN978-3-642-25774-2.

- Hajičová, Eva (1986).Prague Studies in Mathematical Linguistics(9th ed.). John Benjamins Publishing.ISBN978-90-272-1527-7.

- Harkins, William Edward (1952).A Modern Czech Grammar.King's Crown Press (Columbia University).ISBN978-0-231-09937-0.

- Komárek, Miroslav (2012).Dějiny českého jazyka(in Czech). Brno: Host.ISBN978-80-7294-591-7.

- Kortmann, Bernd; van der Auwera, Johan (2011).The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide (World of Linguistics).Mouton De Gruyter.ISBN978-3-11-022025-4.

- Koudela, Břetislav; et al. (1964).Vývoj českého jazyka a dialektologie(in Czech). Československé státní pedagogické nakladatelství.

- Liberman, Anatoly; Trubetskoi, Nikolai S. (2001).N.S. Trubetzkoy: Studies in General Linguistics and Language Structure.Duke UniversityPress.ISBN978-0-8223-2299-3.

- Mann, Stuart Edward (1957).Czech Historical Grammar.Helmut Buske Verlag.ISBN978-3-87118-261-7.

- Mathesius, Vilém (2013).A Functional Analysis of Present Day English on a General Linguistic Basis.De Gruyter.ISBN978-90-279-3077-4.

- Maxwell, Alexander (2009).Choosing Slovakia: Slavic Hungary, the Czechoslovak Language and Accidental Nationalism.Tauris Academic Studies.ISBN978-1-84885-074-3.

- Naughton, James (2005).Czech: An Essential Grammar.Routledge Press.ISBN978-0-415-28785-2.

- Pansofia (1993).Pravidla českého pravopisu(in Czech). Ústav pro jazyk český AV ČR.ISBN978-80-901373-6-3.

- Piotrowski, Michael (2012).Natural Language Processing for Historical Texts.Morgan & Claypool Publishers.ISBN978-1-60845-946-9.

- Qualls, Eduard J. (2012).The Qualls Concise English Grammar.Danaan Press.ISBN978-1-890000-09-7.

- Rothstein, Björn; Thieroff, Rolf (2010).Mood in the Languages of Europe.John Benjamins Publishing Company.ISBN978-90-272-0587-2.

- Short, David (2009). "Czech and Slovak". In Bernard Comrie (ed.).The World's Major Languages(2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 305–330.

- Scheer, Tobias (2004).A Lateral Theory of Phonology: What is CVCV, and why Should it Be?, Part 1.Walter De Gruyter.ISBN978-3-11-017871-5.

- Stankiewicz, Edward (1986).The Slavic Languages: Unity in Diversity.Mouton De Gruyter.ISBN978-3-11-009904-1.

- Sussex, Rolan; Cubberley, Paul (2011).The Slavic Languages.Cambridge Language Surveys.ISBN978-0-521-29448-5.

- Tahal, Karel (2010).A grammar of Czech as a foreign language.Factum.

- Wilson, James (2009).Moravians in Prague: A Sociolinguistic Study of Dialect Contact in the Czech.Peter Lang International Academic Publishers.ISBN978-3-631-58694-5.

External links[edit]

- Ústav pro jazyk český–Czech Language Institute,the regulatory body for the Czech language(in Czech)

- Czech National Corpus

- Czech Monolingual Online Dictionary

- Online Translation Dictionaries

- Czech Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words(from Wiktionary'sSwadesh-list appendix)

- Online Czech Grammar and Exercises