Denisovan

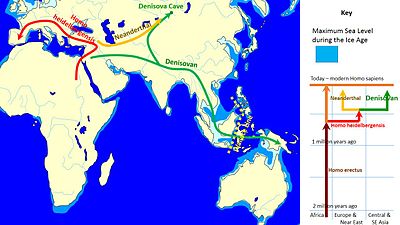

TheDenisovansorDenisova hominins(/dəˈniːsəvə/də-NEE-sə-və) are anextinctspeciesorsubspeciesofarchaic humanthat ranged across Asia during theLowerandMiddle Paleolithic,and lived, based on current evidence, from 285 to 25 thousand years ago.[1]Denisovans are known from few physical remains; consequently, most of what is known about them comes fromDNAevidence. No formal species name has been established pending more complete fossil material.

The first identification of a Denisovan individual occurred in 2010, based onmitochondrial DNA(mtDNA) extracted from ajuvenilefemale finger bone excavated from the SiberianDenisova Cavein theAltai Mountainsin 2008.[2]Nuclear DNAindicates close affinities withNeanderthals.The cave was also periodically inhabited by Neanderthals, but it is unclear whether Neanderthals and Denisovans ever cohabited in the cave. Additional specimens from Denisova Cave were subsequently identified, as was a single specimen from theBaishiya Karst Caveon theTibetan Plateau,and Cobra Cave in theAnnamite Mountainsof Laos. DNA evidence suggests they had dark skin, eyes, and hair, and had a Neanderthal-like build and facial features. However, they had largermolarswhich are reminiscent ofMiddletoLate Pleistocenearchaic humans andaustralopithecines.

Denisovans apparentlyinterbredwith modern humans, with a high percentage (roughly 5%) occurring inMelanesians,Aboriginal Australians,andFilipino Negritos.This distribution suggests that there were Denisovan populations across Asia. There is also evidence of interbreeding with the Altai Neanderthal population, with about 17% of the Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave deriving from them. A first-generation hybrid nicknamed "Denny"was discovered with a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother. Additionally, 4% of the Denisovan genome comes from an unknown archaic human species, which diverged from modern humans over one million years ago.

Taxonomy

[edit]Denisovans may represent a new species ofHomoor an archaic subspecies ofHomo sapiens(modern humans), but there are too few fossils to erect a propertaxon.Proactively proposed species names for Denisovans areH. denisova[3]orH. altaiensis.[4]Chinese researchers suggest the Denisovans were members ofHomo longi,and the idea has been supported by the palaeontologistChris Stringer.[5]

Discovery

[edit]

Denisova Caveis in south-centralSiberia,Russia, in theAltai Mountainsnear the border with Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia. It is named after Denis (Dyonisiy), a Russianhermitwho lived there in the 18th century. The cave was first inspected for fossils in the 1970s by RussianpaleontologistNikolai Ovodov, who was looking for remains ofcanids.[6]

In 2008,Michael Shunkovfrom theRussian Academy of Sciencesand other Russianarchaeologistsfrom the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of theSiberian Branch of the Russian Academy of SciencesinNovosibirskAkademgorodokinvestigated the cave and found the finger bone of a juvenile femalehomininoriginally dated to 50–30,000 years ago.[2][7]The estimate has changed to 76,200–51,600 years ago.[8]The specimen was originally named X-woman becausematrilinealmitochondrial DNA(mtDNA) extracted from the bone demonstrated it to belong to a novel ancient hominin, genetically distinct both from contemporary modern humans and fromNeanderthals.[2]

In 2019, Greek archaeologistKaterina Doukaand colleaguesradiocarbon datedspecimens from Denisova Cave, and estimated that Denisova 2 (the oldest specimen) lived 195,000–122,700 years ago.[8]Older Denisovan DNA collected from sediments in the East Chamber dates to 217,000 years ago. Based onartifactsalso discovered in the cave, hominin occupation (most likely by Denisovans) began 287±41 or 203±14ka.Neanderthals were also present 193±12 ka and 97±11 ka, possibly concurrently with Denisovans.[9]

Specimens

[edit]The fossils of multiple distinct Denisovan individuals fromDenisova Cavehave been identified through theirancient DNA(aDNA): Denisova 2, 3, 4, 8,11,and 25. An mtDNA-based phylogenetic analysis of these individuals suggested that Denisova 2 is the oldest, followed by Denisova 8, while Denisova 3 and Denisova 4 were roughly contemporaneous.[10]In 2024, scientists announced the sequence of Denisova 25, which was in a layer dated to 200ka.[11]During DNA sequencing, a low proportion of the Denisova 2, Denisova 4 and Denisova 8 genomes were found to have survived, but a high proportion of the Denisova 3 and Denisova 25 genomes were intact.[10][12][11]The Denisova 3 sample was cut into two, and the initial DNA sequencing of one fragment was later independently confirmed by sequencing the mtDNA from the second.[13]

Denisova Cave contained the only known examples of Denisovans until 2019, when a research group led byFahu Chen,Dongju Zhang,andJean-Jacques Hublindescribed a partial mandible discovered in 1980 by aBuddhist monkin theBaishiya Karst Caveon theTibetan Plateauin China. Known as theXiahe mandible,the fossil became part of the collection ofLanzhou University,where it remained unstudied until 2010.[14]It was determined byancient proteinanalysis to containcollagenthat by sequence was found to have close affiliation to that of the Denisovans from Denisova Cave, whileuranium decaydating of thecarbonatecrust enshrouding the specimen indicated it was more than 160,000 years old.[15]The identity of this population was later confirmed through study ofenvironmental DNA,which found Denisovan mtDNA in sediment layers ranging in date from 100,000 to 60,000 years before present, and perhaps more recent.[16]

In 2018, a team of Laotian, French, and American anthropologists, who had been excavating caves in the Laotian jungle of theAnnamite Mountainssince 2008, was directed by local children to the site Tam Ngu Hao 2 ( "Cobra Cave" ) where they recovered a human tooth. The tooth (catalogue number TNH2-1) developmentally matches a 3.5 to 8.5 year old, and a lack ofamelogenin(a protein on theY chromosome) suggests it belonged to a girl barring extreme degradation of the protein over a long period of time. Dental proteome analysis was inconclusive for this specimen, but the team found it anatomically comparable with the Xiahe mandible, and so tentatively categorized it as a Denisovan, although they could not rule out it being Neanderthal. The tooth probably dates to 164,000 to 131,000 years ago.[17]

In 2024 aZooMSanalysis of more than 2,500 bones found in Baishiya Karst Cave revealed a further bone fragment; a rib bone dating from between 48,000 BP and 32,000 BP. The conclusion of the ZooMS analysis was there was no evidence of any other human group having occupied the cave. Other bone fragments included a large number ofblue sheep,wild yaks,woolly rhino,spotted hyena,marmots,other small mammals and birds. Examination of the animal bone surfaces indicates the Denisovans removed meat and bone marrow from the bones and also show the humans used them as raw material to make tools. There was also evidence of stone artefacts in each layer excavated.[18][19]

Some older findings may or may not belong to the Denisovan line, but Asia is not well mapped in regards tohuman evolution.Such findings include theDali skull,[20]theXujiayaohominin,[21]Maba Man,theJinniushanhominin, and theNarmada Human.[22]The Xiahe mandible shows morphological similarities to some later East Asian fossils such asPenghu 1,[15][23]but also to ChineseH. erectus.[13]In 2021, Chinese palaeoanthropologist Qiang Ji suggested his newly erected species,H. longi,may represent the Denisovans based on the similarity between the type specimen's molar and that of the Xiahe mandible.[24]

| Name | Fossil elements | Age | Discovery | Place | Sex and age | Publication | Image | GenBank accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denisova 3 (also known asX Woman)[25][13][2] |

Distalphalanxof thefifth finger | 76.2–51.6 ka[8] | 2008 | Denisova cave (Russia) | 13.5-year-old adolescent female | 2010 |  |

NC013993 |

| Denisova 4[25][20] | Permanent upper 2nd or 3rd molar | 84.1–55.2 ka[8] | 2000 | Denisova cave (Russia) | Adult male | 2010 |  |

FR695060 |

| Denisova 8[12] | Permanent upper 3rd molar | 136.4–105.6 ka[8] | 2010 | Denisova cave (Russia) | Adult male | 2015 | KT780370 | |

| Denisova 2[10] | Deciduous2nd lower molar | 194.4–122.7 ka[8] | 1984 | Denisova cave (Russia) | Adolescent female | 2017 | KX663333 | |

| Xiahe mandible[15] | Partial mandible | > 160 ka | 1980 | Baishiya Cave(China) | 2019 |

|

||

| Denisova 11 (also known asDenny,Denisovan x Neanderthal hybrid) [26] |

Arm or leg bone fragment | 118.1–79.3 ka[8] | 2012 | Denisova cave (Russia) | 13 year old adolescent female | 2016 |

|

|

| Denisova 13[27] | Parietal bonefragment | Found in layer 22[27]which dates to ~285±39 ka[9] | 2019 | Denisova cave (Russia) | pending | |||

| TNH2-1[17] | Permanent lower left 1st or 2nd molar | 164–131 ka | 2018 | Tam Ngu Hao 2 cave (Laos) | 3.5 to 8.5 year old female | 2022 |

|

|

| BSY-19-B896-1 (Xiahe 2) | Distal rib fragment | 48–32 ka | 1980 | Baishiya Cave (China) | Unknown | 2024 |

| |

| Denisova 25[11] | Molar | 200 ka | 2024 | Denisova cave (Russia) | Male | pending |

Evolution

[edit]

Sequencedmitochondrial DNA(mtDNA), preserved by the cool climate of the cave (average temperature is at freezing point), was extracted from Denisova 3 by a team of scientists led byJohannes KrauseandSvante Pääbofrom theMax Planck Institute for Evolutionary AnthropologyinLeipzig,Germany. Denisova 3's mtDNA differs from that of modern humans by 385 bases (nucleotides) out of approximately 16,500, whereas the difference between modern humans andNeanderthalsis around 202 bases. In comparison, the difference betweenchimpanzeesand modern humans is approximately 1,462 mtDNA base pairs. This suggested that Denisovan mtDNA diverged from that of modern humans and Neanderthals about 1,313,500–779,300 years ago; whereas modern human and Neanderthal mtDNA diverged 618,000–321,200 years ago. Krause and colleagues then concluded that Denisovans were the descendants of an earlier migration ofH. erectusout of Africa, completely distinct from modern humans and Neanderthals.[2]

However, according to thenuclear DNA(nDNA) of Denisova 3—which had an unusual degree of DNA preservation with only low-level contamination—Denisovans and Neanderthals were more closely related to each other than they were to modern humans. Using the percent distance fromhuman–chimpanzee last common ancestor,Denisovans/Neanderthals split from modern humans about 804,000 years ago, and from each other 640,000 years ago.[25]Using a mutation rate of1×10−9or0.5×10−9perbase pair(bp) per year, the Neanderthal/Denisovan split occurred around either 236–190,000 or 473–381,000 years ago respectively.[28]Using1.1×10−8per generation with a new generation every 29 years, the time is 744,000 years ago. Using5×10−10nucleotidesite per year, it is 616,000 years ago. Using the latter dates, the split had likely already occurred by the time hominins spread out across Europe.[29]H. heidelbergensisis typically considered to have been the direct ancestor of Denisovans and Neanderthals, and sometimes also modern humans.[30]Due to the strong divergence in dental anatomy, they may have split before characteristic Neanderthal dentition evolved about 300,000 years ago.[25]

The more divergent Denisovan mtDNA has been interpreted as evidence of admixture between Denisovans and an unknown archaic human population,[31]possibly arelictH. erectusorH. erectus-like population about 53,000 years ago.[28]Alternatively, divergent mtDNA could have also resulted from the persistence of an ancient mtDNA lineage which only went extinct in modern humans and Neanderthals throughgenetic drift.[25]Modern humans contributed mtDNA to the Neanderthal lineage, but not to the Denisovan mitochondrial genomes yet sequenced.[32][33][34][35]The mtDNA sequence from the femur of a 400,000-year-oldH. heidelbergensisfrom theSima de los Huesos Cavein Spain was found to be related to those of Neanderthals and Denisovans, but closer to Denisovans,[36][37]and the authors posited that this mtDNA represents an archaic sequence which was subsequently lost in Neanderthals due to replacement by a modern-human-related sequence.[38]

Demographics

[edit]

Denisovans are known to have lived in Siberia, Tibet, and Laos.[17]The Xiahe mandible is the earliest recorded human presence on the Tibetan Plateau.[15]Though their remains have been identified in only these three locations, traces of Denisovan DNA in modern humans suggest they ranged acrossEast Asia,[39][40]and potentially western Eurasia.[41]In 2019,geneticistGuy Jacobs and colleagues identified three distinct populations of Denisovans responsible for the introgression into modern populations now native to, respectively: Siberia and East Asia; New Guinea and nearby islands; andOceaniaand, to a lesser extent, across Asia. Usingcoalescent modeling,the Denisova Cave Denisovans split from the second population about 283,000 years ago; and from the third population about 363,000 years ago. This indicates that there was considerable reproductive isolation between Denisovan populations.[42]In a 2024 study, scientist Danat Yermakovich, of theUniversity of Tartu,discovered that people living at different elevations in Papa New Guinea have differences in Denisovan DNA; with people living in the highlands having variants for early brain development and those living in the lowlands having variants for the immune system.[43]

Based on the high percentages of Denisovan DNA in modern Papuans and Australians, Denisovans may have crossed theWallace Lineinto these regions (with little back-migration west), the second known human species to do so,[22]along with earlierHomo floresiensis.By this logic, they may have also entered the Philippines, living alongsideH. luzonensiswhich, if this is the case, may represent the same or a closely related species.[44]These Denisovans may have needed to cross large bodies of water.[42]Alternately, high Denisovan DNA admixture in modern Papuan populations may simply represent higher mi xing among the original ancestors of Papuans prior to crossing the Wallace line. Icelanders also have an anomalously high Denisovan heritage, which could have stemmed from a Denisovan population far west of the Altai mountains. Genetic data suggests Neanderthals were frequently making long crossings between Europe and the Altai mountains especially towards the date of their extinction.[41]

Usingexponential distributionanalysis onhaplotypelengths, Jacobs calculatedintrogressioninto modern humans occurred about 29,900 years ago with the Denisovan population ancestral to New Guineans; and 45,700 years ago with the population ancestral to both New Guineans and Oceanians. Such a late date for the New Guinean group could indicate Denisovan survival as late as 14,500 years ago, which would make them the latest surviving archaic human species. A third wave appears to have introgressed into East Asia, but there is not enough DNA evidence to pinpoint a solid timeframe.[42]

The mtDNA from Denisova 4 bore a high similarity to that of Denisova 3, indicating that they belonged to the same population.[25]Thegenetic diversityamong the Denisovans from Denisova Cave is on the lower range of what is seen in modern humans, and is comparable to that of Neanderthals. However, it is possible that the inhabitants of Denisova Cave were more or less reproductively isolated from other Denisovans, and that, across their entire range, Denisovan genetic diversity may have been much higher.[10]

Denisova Cave, over time of habitation, continually swung from a fairly warm and moderately humid pine and birch forest to tundra or forest-tundra landscape.[9]Conversely, Baishiya Karst Cave is situated at a high elevation, an area characterized by low temperature, low oxygen, and poor resource availability. Colonization of high-altitude regions, due to such harsh conditions, was previously assumed to have only been accomplished by modern humans.[15]Denisovans seem to have also inhabited the jungles of Southeast Asia.[40]The Tam Ngu Hao 2 site might have been a closed forest environment.[17]

Anatomy

[edit]Little is known of the precise anatomical features of the Denisovans since the only physical remains discovered so far are a finger bone, four teeth,long bonefragments, a partial jawbone,[14][17]aparietal boneskull fragment,[27]and a rib bone.[18][19]The finger bone is within the modern human range of variation for women,[13]which is in contrast to the large, robust molars which are more similar to those of Middle to Late Pleistocene archaic humans. The third molar is outside the range of anyHomospecies exceptH. habilisandH. rudolfensis,and is more like those ofaustralopithecines.The second molar is larger than those of modern humans and Neanderthals, and is more similar to those ofH. erectusandH. habilis.[25]Like Neanderthals, the mandible had a gap behind the molars, and the front teeth were flattened; but Denisovans lacked a high mandibular body, and themandibular symphysisat the midline of the jaw was more receding.[15][23]The parietal is reminiscent of that ofH. erectus.[45]

A facial reconstruction has been generated by comparingmethylationat individual genetic loci associated with facial structure.[46]This analysis suggested that Denisovans, much like Neanderthals, had a long, broad, and projecting face; large nose; sloping forehead; protruding jaw; elongated and flattened skull; and wide chest and hips. The Denisovantooth rowwas longer than that of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans.[47]

Middle-to-Late Pleistocene East Asian archaic human skullcaps typically share features with Neanderthals. The skullcaps from Xuchang feature prominent brow ridges like Neanderthals, though the nuchal and angular tori near the base of the skull are either reduced or absent, and the back of the skull is rounded off like inearly modern humans.Xuchang 1 had a large brain volume of approximately 1800 cc, on the high end for Neanderthals and early modern humans, and well beyond the present-day human average.[48]

The Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave has variants of genes which, in modern humans, are associated with dark skin, brown hair, and brown eyes.[49]The Denisovan genome also contains a variant region around theEPAS1gene that inTibetansassists with adaptation to low oxygen levels at high elevation,[50][15]and in a region containing theWARS2andTBX15loci which affect body-fat distribution in theInuit.[51]In Papuans, introgressed Neanderthal alleles are highest in frequency in genes expressed in the brain, whereas Denisovan alleles have highest frequency in genes expressed in bones and other tissue.[52]

Culture

[edit]Denisova Cave

[edit]EarlyMiddle Paleolithicstone tools from Denisova Cave includedcores,scrapers,denticulate tools,and notched tools, deposited about 287±41 thousand years ago in the Main Chamber of the cave; and about 269±97 thousand years ago in the South Chamber; up to 170±19 thousand and 187±14 thousand years ago in the Main and East Chambers, respectively.[9]

Middle Paleolithic assemblages were dominated by flat, discoidal, and Levallois cores, and there were some isolated sub-prismatic cores. There were predominantly side scrapers (a scraper with only the sides used to scrape), but also notched-denticulate tools, end-scrapers (a scraper with only the ends used to scrape),burins,chisel-like tools, and truncated flakes. These dated to 156±15 thousand years ago in the Main Chamber, 58±6 thousand years ago in the East Chamber, and 136±26–47±8 thousand years ago in the South Chamber.[9]

EarlyUpper Paleolithicartefacts date to 44±5 thousand years ago in the Main Chamber, 63±6 thousand years ago in the East Chamber, and 47±8 thousand years ago in the South Chamber, though some layers of the East Chamber seem to have been disturbed. There wasbladeproduction and Levallois production, but scrapers were again predominant. A well-developed, Upper Paleolithic stone bladelet technology distinct from the previous scrapers began accumulating in the Main Chamber around 36±4 thousand years ago.[9]

In the Upper Paleolithic layers, there were also severalbone toolsand ornaments: amarblering, an ivory ring, an ivory pendant, ared deertooth pendant, anelktooth pendant, achloritolitebracelet, and a bone needle. However, Denisovans are only confirmed to have inhabited the cave until 55 ka; the dating of Upper Paleolithic artefacts overlaps with modern human migration into Siberia (though there are no occurrences in the Altai region); and the DNA of the only specimen in the cave dating to the time interval (Denisova 14) is too degraded to confirm species identity, so the attribution of these artefacts is unclear.[53][9]

Tibet

[edit]In 1998, five child hand- and footprint impressions were discovered in atravertineunitnear the Quesanghot springsin Tibet; in 2021, they were dated to 226 to 169 thousand years ago using uranium decay dating. This is the oldest evidence of human occupation of the Tibetan Plateau, and since the Xiahe mandible is the oldest human fossil from the region (though younger than the Quesang impressions), these may have been made by Denisovan children. The impressions were printed onto a small panel of space, and there is little overlap between all the prints, so they seem to have been taking care to make new imprints in unused space. If considered art, they are the oldest known examples ofrock art.Similar hand stencils and impressions do not appear again in the archeological record until roughly 40,000 years ago.[54]

The footprints comprise four right impressions and one left superimposed on one of the rights. They were probably left by two individuals. The tracks of the individual who superimposed their left onto their right may have scrunched up their toes and wiggled them in the mud, or dug their finger into the toe prints. The footprints average 192.3 mm (7.57 in) long, which roughly equates to a 7 or 8 year old child by modern human growth rates. There are two sets of handprints (from a left and right hand), which may have been created by an older child unless one of the former two individuals had long fingers. The handprints average 161.1 mm (6.34 in), which roughly equates with a 12 year old modern human child, and the middle finger length agrees with a 17 year old modern human. One of the handprints shows an impression of the forearm, and the individual was wiggling their thumb through the mud.[54]

Interbreeding

[edit]Analyses of the modern human genomes indicate past interbreeding with at least two groups of archaic humans, Neanderthals[55]and Denisovans,[25][56]and that such interbreeding events occurred on multiple occasions. Comparisons of the Denisovan, Neanderthal, and modern human genomes have revealed evidence of a complex web of interbreeding among these lineages.[55]

Archaic humans

[edit]As much as 17% of the Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave represents DNA from the local Neanderthal population.[55]Denisova 11 was anF1(first generation) Denisovan/Neanderthal hybrid; the fact that such an individual was found may indicate interbreeding was a common occurrence here.[57]The Denisovan genome shares more derived alleles with the Altai Neanderthal genome from Siberia than with theVindija CaveNeanderthal genome from Croatia or theMezmaiskaya caveNeanderthal genome from the Caucasus, suggesting that the gene flow came from a population that was more closely related to the local Altai Neanderthals.[58]However, Denny's Denisovan father had the typical Altai Neanderthalintrogression,while her Neanderthal mother represented a population more closely related to Vindija Neanderthals.[59]Denisova 25, dated to 200ka, is estimated to have inherited 5% of his genome from a previously unknown population of Neanderthals, and came from a different population of Denisovans than the younger samples.[11]

About 4% of the Denisovan genome derives from an unidentified archaic hominin,[55]perhaps the source of the anomalous ancient mtDNA, indicating this species diverged from Neanderthals and humans over a million years ago. The only identifiedHomospecies ofLate PleistoceneAsia areH. erectusandH. heidelbergensis,[58][60]though in 2021, specimens allocated to the latter species were reclassified asH. longiandH. daliensis.[61]

Before splitting from Neanderthals, their ancestors ( "Neandersovans" ) migrating into Europe apparently interbred with an unidentified "superarchaic" human species who were already present there; these superarchaics were the descendants of a very early migration out of Africa around 1.9 mya.[62]

Modern humans

[edit]−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A 2011 study found that Denisovan DNA is prevalent inPapuans,Aboriginal Australians,Near Oceanians,Polynesians,Fi gian s,EasternIndonesians,andAeta(from the Philippines); but not inEast Asians,western Indonesians,Jahai people(from Malaysia), orOnge(from theAndaman Islands). This may suggest that Denisovan introgression occurred within the Pacific region rather than on the Asian mainland, and that ancestors of the latter groups were not present in Southeast Asia at the time.[40][63]In theMelanesiangenome, about 4–6%[25]or 1.9–3.4% derives from Denisovan introgression.[64]Prior to 2021, New Guineans and Australian Aborigines were reported to have the most introgressed DNA,[22]but Australians have less than New Guineans.[65]A 2021 study discovered 30 to 40% more Denisovan ancestry inAeta peoplein the Philippines than inPapuans,estimated as about 5% of the genome. The Aeta Magbukon in Luzon have the highest known proportion of Denisovan ancestry of any population in the world.[44]In Papuans, less Denisovan ancestry is seen in theX chromosomethanautosomes,and some autosomes (such aschromosome 11) also have less Denisovan ancestry, which could indicatehybrid incompatibility.The former observation could also be explained by less female Denisovan introgression into modern humans, or more female modern human immigrants who diluted Denisovan X chromosome ancestry.[49]

In contrast, 0.2% derives from Denisovan ancestry in mainland Asians andNative Americans.[66]South Asianswere found to have levels of Denisovan admixture similar to that seen in East Asians.[67]The discovery of the 40,000-year-old Chinese modern humanTianyuan Manlacking Denisovan DNA significantly different from the levels in modern-day East Asians discounts the hypothesis that immigrating modern humans simply diluted Denisovan ancestry whereas Melanesians lived in reproductive isolation.[68][22]A 2018 study of Han Chinese,Japanese,andDaigenomes showed that modern East Asians have DNA from two different Denisovan populations: one similar to the Denisovan DNA found in Papuan genomes, and a second that is closer to the Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave. This could indicate two separate introgression events involving two different Denisovan populations. In South Asian genomes, DNA only came from the same single Denisovan introgression seen in Papuans.[67]A 2019 study found a third wave of Denisovans which introgressed into East Asians. Introgression, also, may not have immediately occurred when modern humans immigrated into the region.[42]

The timing of introgression into Oceanian populations likely occurred after Eurasians and Oceanians split roughly 58,000 years ago, and before Papuan and Aboriginal Australians split from each other roughly 37,000 years ago. Given the present day distribution of Denisovan DNA, this may have taken place in Wallacea, though the discovery of a 7,200 year oldToaleangirl (closely related to Papuans and Aboriginal Australians) from Sulawesi carrying Denisovan DNA makes Sundaland another potential candidate. Other early Sunda hunter gatherers so far sequenced carry very little Denisovan DNA, which either means the introgression event did not take place in Sundaland, or Denisovan ancestry was diluted with gene flow from the mainland AsianHòabìnhianculture and subsequentNeolithiccultures.[69]

In other regions of the world, archaic introgression into humans stems from a group of Neanderthals related to those which inhabitedVindija Cave,Croatia, as opposed to archaics related to Siberian Neanderthals and Denisovans. However, about 3.3% of the archaic DNA in the modern Icelandic genome descends from the Denisovans, and such a high percentage could indicate a western Eurasian population of Denisovans which introgressed into either Vindija-related Neanderthals or immigrating modern humans.[41]

Denisovan genes may have helped early modern humans migrating out of Africa to acclimatize[citation needed].Although not present in the sequenced Denisovan genome, the distribution pattern and divergence of HLA-B*73 from otherHLAalleles (involved in theimmune system'snatural killer cell receptors) has led to the suggestion that it introgressed from Denisovans into modern humans inWest Asia.In a 2011 study, half of the HLA alleles of modern Eurasians were shown to represent archaic HLA haplotypes, and were inferred to be of Denisovan or Neanderthal origin.[70]A haplotype of EPAS1 in modern Tibetans, which allows them to live at high elevations in a low-oxygen environment, likely came from Denisovans.[50][15]Genes related tophospholipidtransporters (which are involved infat metabolism) and totrace amine-associated receptors(involved in smelling) are more active in people with more Denisovan ancestry.[71]Denisovan genes may have conferred a degree of immunity against the G614 mutation ofSARS-CoV-2.[72]Denisovan introgressions may have influenced the immune system of present-day Papuans and potentially favoured "variants to immune-related phenotypes" and "adaptation to the local environment".[73]

In December 2023, scientists reported thatgenesinherited bymodern humansfromNeanderthalsand Denisovans may biologically influence the daily routine of modern humans.[74]

See also

[edit]- Red Deer Cave people– Prehistoric humans from 12,500 BCE in southwest China

- Homo longi– Archaic human from China, 146,000 BP

- Homo naledi– South African archaic human species

- Nesher RamlaHomo– Extinct population of archaic humans

- Timeline of human evolution

References

[edit]- ^Zimmer, Carl(2 March 2024)."On the Trail of the Denisovans - DNA has shown that the extinct humans thrived around the world, from chilly Siberia to high-altitude Tibet — perhaps even in the Pacific islands".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 2 March 2024.Retrieved2 March2024.

- ^abcdeKrause, J.; Fu, Q.; Good, J. M.; Viola, B.; et al. (2010)."The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia".Nature.464(7290): 894–897.Bibcode:2010Natur.464..894K.doi:10.1038/nature08976.ISSN1476-4687.PMC10152974.PMID20336068.S2CID4415601.

- ^Douglas, M. M.; Douglas, J. M. (2016).Exploring Human Biology in the Laboratory.Morton Publishing Company. p. 324.ISBN9781617313905.

- ^Zubova, A.; Chikisheva, T.; Shunkov, M. V. (2017)."The Morphology of Permanent Molars from the Paleolithic Layers of Denisova Cave".Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia.45:121–134.doi:10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.1.121-134.

- ^McKie, Robin (30 March 2024)."Scientists link elusive human group to 150,000-year-old Chinese 'dragon man'".The Observer.ISSN0029-7712.Retrieved31 March2024.

- ^Ovodov, N. D.; Crockford, S. J.; Kuzmin, Y. V.; Higham, T. F.; et al. (2011)."A 33,000-Year-Old Incipient Dog from the Altai Mountains of Siberia: Evidence of the Earliest Domestication Disrupted by the Last Glacial Maximum".PLOS ONE.6(7): e22821.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622821O.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022821.PMC3145761.PMID21829526.

- ^Reich, D.(2018).Who We Are and How We Got Here.Oxford University Press.p. 53.ISBN978-0-19-882125-0.

- ^abcdefgDouka, K. (2019)."Age estimates for hominin fossils and the onset of the Upper Palaeolithic at Denisova Cave".Nature.565(7741): 640–644.Bibcode:2019Natur.565..640D.doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0870-z.PMID30700871.S2CID59525455.Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2020.Retrieved7 December2019.

- ^abcdefgJacobs, Zenobia; Li, Bo; Shunkov, Michael V.; Kozlikin, Maxim B.; et al. (January 2019)."Timing of archaic hominin occupation of Denisova Cave in southern Siberia".Nature.565(7741): 594–599.Bibcode:2019Natur.565..594J.doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0843-2.ISSN1476-4687.PMID30700870.S2CID59525956.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2020.Retrieved29 May2020.

- ^abcdSlon, V.;Viola, B.; Renaud, G.; Gansauge, M.-T.; et al. (2017)."A fourth Denisovan individual".Science Advances.3(7): e1700186.Bibcode:2017SciA....3E0186S.doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700186.PMC5501502.PMID28695206.

- ^abcdGibbons, Ann (11 July 2024)."The most ancient human genome yet has been sequenced—and it's a Denisovan's".Science.doi:10.1126/science.zi9n4zp.

- ^abSawyer, S.; Renaud, G.; Viola, B.; Hublin, J.-J.; et al. (2015)."Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences from two Denisovan individuals".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.112(51): 15696–700.Bibcode:2015PNAS..11215696S.doi:10.1073/pnas.1519905112.PMC4697428.PMID26630009.

- ^abcdBennett, E. A.; Crevecoeur, I.; Viola, B.; et al. (2019)."Morphology of the Denisovan phalanx closer to modern humans than to Neanderthals".Science Advances.5(9): eaaw3950.Bibcode:2019SciA....5.3950B.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw3950.PMC6726440.PMID31517046.

- ^abGibbons, Anne (2019). "First fossil jaw of Denisovans finally puts a face on elusive human relatives".Science.doi:10.1126/science.aax8845.S2CID188493848.

- ^abcdefghChen, F.;Welker, F.; Shen, C.-C.; et al. (2019)."A late Middle Pleistocene Denisovan mandible from the Tibetan Plateau"(PDF).Nature.569(7756): 409–412.Bibcode:2019Natur.569..409C.doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1139-x.PMID31043746.S2CID141503768.Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 December 2019.Retrieved7 December2019.

- ^Shang, D.; et al. (2020). "Denisovan DNA in Late Pleistocene sediments from Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau".Science.370(6516): 584–587.doi:10.1126/science.abb6320.PMID33122381.S2CID225956074.

- ^abcdeDemeter, F.; Zanolli, C.; Westaway, K. E.; et al. (2022)."A Middle Pleistocene Denisovan molar from the Annamite Chain of northern Laos".Nature Communications.13(2557): 2557.Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.2557D.doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29923-z.PMC9114389.PMID35581187.

- ^ab"Extinct humans survived on the Tibetan plateau for 160,000 years".ScienceDaily.3 July 2024.Retrieved5 July2024.

- ^abXia, Huan; Zhang, Dongju; Wang, Jian; Fagernäs, Zandra; Li, Ting; Li, Yuanxin; Yao, Juanting; Lin, Dongpeng; Troché, Gaudry; Smith, Geoff M.; Chen, Xiaoshan; Cheng, Ting; Shen, Xuke; Han, Yuanyuan; Olsen, Jesper V. (3 July 2024)."Middle and Late Pleistocene Denisovan subsistence at Baishiya Karst Cave".Nature.632(8023): 108–113.doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07612-9.ISSN1476-4687.PMC11291277.PMID38961285.

- ^abCallaway, Ewen (2010)."Fossil genome reveals ancestral link".Nature.468(7327): 1012.Bibcode:2010Natur.468.1012C.doi:10.1038/4681012a.PMID21179140.

- ^Ao, H.; Liu, C.-R.; Roberts, A. P. (2017)."An updated age for the Xujiayao hominin from the Nihewan Basin, North China: Implications for Middle Pleistocene human evolution in East Asia".Journal of Human Evolution.106:54–65.Bibcode:2017AGUFMPP13B1080A.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.01.014.hdl:1885/232536.PMID28434540.

- ^abcdeCooper, A.;Stringer, C. B.(2013). "Did the Denisovans Cross Wallace's Line?".Science.342(6156): 321–23.Bibcode:2013Sci...342..321C.doi:10.1126/science.1244869.PMID24136958.S2CID206551893.

- ^abWarren, M. (2019)."Biggest Denisovan fossil yet spills ancient human's secrets".Nature News.569(7754): 16–17.Bibcode:2019Natur.569...16W.doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01395-0.PMID31043736.

- ^Ji, Qiang; Wu, Wensheng; Ji, Yannan; Li, Qiang; et al. (25 June 2021)."Late Middle Pleistocene Harbin cranium represents a new Homo species".The Innovation.2(3): 100132.Bibcode:2021Innov...200132J.doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100132.ISSN2666-6758.PMC8454552.PMID34557772.

- ^abcdefghiReich, D.;Green, R. E.; Kircher, M.; et al. (2010)."Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia"(PDF).Nature.468(7327): 1053–60.Bibcode:2010Natur.468.1053R.doi:10.1038/nature09710.hdl:10230/25596.PMC4306417.PMID21179161.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2020.Retrieved29 July2018.

- ^Brown, S.; Higham, T.; Slon, V.;Pääbo, S.(2016)."Identification of a new hominin bone from Denisova Cave, Siberia using collagen fingerprinting and mitochondrial DNA analysis".Scientific Reports.6:23559.Bibcode:2016NatSR...623559B.doi:10.1038/srep23559.PMC4810434.PMID27020421.

- ^abcViola, B. T.; Gunz, P.; Neubauer, S. (2019)."A parietal fragment from Denisova cave".88th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists.Archivedfrom the original on 26 September 2019.Retrieved18 January2020.

- ^abLao, O.; Bertranpetit, J.; Mondal, M. (2019)."Approximate Bayesian computation with deep learning supports a third archaic introgression in Asia and Oceania".Nature Communications.10(1): 246.Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..246M.doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08089-7.ISSN2041-1723.PMC6335398.PMID30651539.

- ^Rogers, A. R.; Bohlender, R. J.; Huff, C. D. (2017)."Early history of Neanderthals and Denisovans".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.114(37): 9859–9863.Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.9859R.doi:10.1073/pnas.1706426114.PMC5604018.PMID28784789.

- ^Ho, K. K. (2016)."Hominin interbreeding and the evolution of human variation".Journal of Biological Research-Thessaloniki.23:17.doi:10.1186/s40709-016-0054-7.PMC4947341.PMID27429943.

- ^Malyarchuk, B. A. (2011). "Adaptive evolution of theHomomitochondrial genome ".Molecular Biology.45(5): 845–850.doi:10.1134/S0026893311050104.PMID22393781.S2CID43284294.

- ^Pääbo, S.;Kelso, J.;Reich, D.;Slatkin, M.; et al. (2014)."The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains".Nature.505(7481): 43–49.Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P.doi:10.1038/nature12886.ISSN1476-4687.PMC4031459.PMID24352235.

- ^Kuhlwilm, M.; Gronau, I.; Hubisz, M. J.; de Filippo, C.; et al. (2016)."Ancient gene flow from early modern humans into Eastern Neanderthals".Nature.530(7591): 429–433.Bibcode:2016Natur.530..429K.doi:10.1038/nature16544.ISSN1476-4687.PMC4933530.PMID26886800.

- ^Posth, C.; Wißing, C.; Kitagawa, K.; Pagani, L.; et al. (2017)."Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals".Nature Communications.8:16046.Bibcode:2017NatCo...816046P.doi:10.1038/ncomms16046.ISSN2041-1723.PMC5500885.PMID28675384.

- ^Bertranpetit, J.; Majumder, P. P.; Li, Q.; Laayouni, H.; et al. (2016). "Genomic analysis of Andamanese provides insights into ancient human migration into Asia and adaptation".Nature Genetics.48(9): 1066–1070.doi:10.1038/ng.3621.hdl:10230/34401.ISSN1546-1718.PMID27455350.S2CID205352099.

- ^Callaway, E. (2013)."Hominin DNA baffles experts".Nature.504(7478): 16–17.Bibcode:2013Natur.504...16C.doi:10.1038/504016a.PMID24305130.

- ^Tattersall, I.(2015).The Strange Case of the Rickety Cossack and other Cautionary Tales from Human Evolution.Palgrave Macmillan.p. 200.ISBN978-1-137-27889-0.

- ^Meyer, M.; Arsuaga, J.-L.; et al. (2016). "Nuclear DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos hominins".Nature.531(7595): 504–507.Bibcode:2016Natur.531..504M.doi:10.1038/nature17405.PMID26976447.S2CID4467094.

- ^Callaway, E. (2011). "First Aboriginal genome sequenced".Nature News.doi:10.1038/news.2011.551.

- ^abcReich, David; Patterson, Nick; Kircher, Martin; Delfin, Frederick; et al. (2011)."Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania".The American Journal of Human Genetics.89(4): 516–28.doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005.PMC3188841.PMID21944045.

- ^abcSkov, L.; Macià, M. C.; Sveinbjörnsson, G.; et al. (2020). "The nature of Neanderthal introgression revealed by 27,566 Icelandic genomes".Nature.582(7810): 78–83.Bibcode:2020Natur.582...78S.doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2225-9.PMID32494067.S2CID216076889.

- ^abcdJacobs, G. S.; Hudjashov, G.; Saag, L.; Kusuma, P.; et al. (2019)."Multiple Deeply Divergent Denisovan Ancestries in Papuans".Cell.177(4): 1010–1021.e32.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.035.hdl:1983/7df38af7-d075-4444-9111-b859650f6d38.ISSN0092-8674.PMID30981557.

- ^"Denisovan DNA may help modern humans adapt to different environments".

- ^abLarena, Maximilian; McKenna, James; Sanchez-Quinto, Federico; Bernhardsson, Carolina; et al. (August 2021)."Philippine Ayta possess the highest level of Denisovan ancestry in the world".Current Biology.31(19): 4219–4230.e10.Bibcode:2021CBio...31E4219L.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.07.022.PMC8596304.PMID34388371.S2CID236994320.

- ^Callaway, E. (2019)."Siberia's ancient ghost clan starts to surrender its secrets".Nature News.566(7745): 444–446.Bibcode:2019Natur.566..444C.doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00672-2.PMID30814723.

- ^Gokhman, D.; Lavi, E.; Prüfer, K.; Fraga, M. F.; et al. (2014)."Reconstructing the DNA methylation maps of the Neandertal and the Denisovan".Science.344(6183): 523–27.Bibcode:2014Sci...344..523G.doi:10.1126/science.1250368.PMID24786081.S2CID28665590.

- ^Gokhman, D.; Mishol, N.; de Manuel, M.; Marques-Bonet, T.; et al. (2019)."Reconstructing Denisovan Anatomy Using DNA Methylation Maps".Cell.179(1): 180–192.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.035.PMID31539495.S2CID202676502.

- ^Li, Z.-Y.; Wu, X.-J.; Zhou, L.-.P; et al. (2017). "Late Pleistocene archaic human crania from Xuchang, China".Science.355(6328): 969–972.Bibcode:2017Sci...355..969L.doi:10.1126/science.aal2482.PMID28254945.S2CID206654741.

- ^abMeyer, M.; Kircher, M.; Gansauge, M.-T.; et al. (2012)."A High-Coverage Genome Sequence from an Archaic Denisovan Individual".Science.338(6104): 222–226.Bibcode:2012Sci...338..222M.doi:10.1126/science.1224344.PMC3617501.PMID22936568.

- ^abHuerta-Sánchez, E.; Jin, X.; et al. (2014)."Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA".Nature.512(7513): 194–97.Bibcode:2014Natur.512..194H.doi:10.1038/nature13408.PMC4134395.PMID25043035.

- ^Racimo, Fernando; Gokhman, David; Fumagalli, Matteo; Ko, Amy; et al. (2017)."Archaic Adaptive Introgression in TBX15/WARS2".Molecular Biology and Evolution.34(3): 509–524.doi:10.1093/molbev/msw283.PMC5430617.PMID28007980.

- ^Akkuratov, Evgeny E.; Gelfand, Mikhail S.; Khrameeva, Ekaterina E. (2018). "Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry in Papuans: A functional study".Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology.16(2): 1840011.doi:10.1142/S0219720018400115.PMID29739306.

- ^Dennell, R. (2019)."Dating of hominin discoveries at Denisova".Nature News.565(7741): 571–572.Bibcode:2019Natur.565..571D.doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00264-0.PMID30700881.

- ^abZhang, D. D.; Bennett, M. R.; Cheng, H.; Wang, L.; et al. (2021)."Earliest parietal art: Hominin hand and foot traces from the middle Pleistocene of Tibet".Science Bulletin.66(24): 2506–2515.Bibcode:2021SciBu..66.2506Z.doi:10.1016/j.scib.2021.09.001.ISSN2095-9273.PMID36654210.S2CID239102132.

- ^abcdPennisi, E.(2013). "More Genomes from Denisova Cave Show Mi xing of Early Human Groups".Science.340(6134): 799.Bibcode:2013Sci...340..799P.doi:10.1126/science.340.6134.799.PMID23687020.

- ^Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, et al. (2010)."A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome"(PDF).Science.328(5979): 710–22.Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G.doi:10.1126/science.1188021.PMC5100745.PMID20448178.Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 August 2012.Retrieved3 May2013.

- ^Warren, M. (2018)."Mum's a Neanderthal, Dad's a Denisovan: First discovery of an ancient-human hybrid – Genetic analysis uncovers a direct descendant of two different groups of early humans".Nature.560(7719): 417–418.Bibcode:2018Natur.560..417W.doi:10.1038/d41586-018-06004-0.PMID30135540.

- ^abPrüfer, K.; Racimo, Fernando; Patterson, N.; Jay, F.; Sankararaman, S.; Sawyer, S.; et al. (2013)."The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains".Nature.505(7481): 43–49.Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P.doi:10.1038/nature12886.PMC4031459.PMID24352235.

- ^Warren, Matthew (2018)."Mum's a Neanderthal, Dad's a Denisovan: First discovery of an ancient-human hybrid".Nature.560(7719): 417–18.Bibcode:2018Natur.560..417W.doi:10.1038/d41586-018-06004-0.PMID30135540.

- ^Wolf, A. B.; Akey, J. M. (2018)."Outstanding questions in the study of archaic hominin admixture".PLOS Genetics.14(5): e1007349.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007349.PMC5978786.PMID29852022.

- ^Ni, X.; Ji, Q.; Wu, W.; et al. (2021)."Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage".Innovation.2(3): 100130.Bibcode:2021Innov...200130N.doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130.ISSN2666-6758.PMC8454562.PMID34557770.S2CID236784246.

- ^Rogers, A. R.; Harris, N. S.; Achenbach, A. A. (2020)."Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors interbred with a distantly related hominin".Science Advances.6(8): eaay5483.Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5483R.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay5483.PMC7032934.PMID32128408.

- ^Yang, Melinda A. (6 January 2022)."A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia".Human Population Genetics and Genomics.2(1): 1–32.doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001.ISSN2770-5005.

- ^Vernot, B.; et al. (2016)."Excavating Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from the genomes of Melanesian individuals".Science.352(6282): 235–239.Bibcode:2016Sci...352..235V.doi:10.1126/science.aad9416.PMC6743480.PMID26989198.

- ^Rasmussen, M.; Guo, Xiaosen; Wang, Yong; Lohmueller, Kirk E.; Rasmussen, Simon; et al. (2011)."An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia".Science.334(6052): 94–98.Bibcode:2011Sci...334...94R.doi:10.1126/science.1211177.PMC3991479.PMID21940856.

- ^Prüfer, K.; Racimo, F.; Patterson, N.; Jay, F.; et al. (2013)."The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains".Nature.505(7481): 43–49.Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P.doi:10.1038/nature12886.PMC4031459.PMID24352235.

- ^abBrowning, S. R.;Browning, B. L.; Zhou, Yi.; Tucci, S.; et al. (2018)."Analysis of Human Sequence Data Reveals Two Pulses of Archaic Denisovan Admixture".Cell.173(1): 53–61.e9.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.031.ISSN0092-8674.PMC5866234.PMID29551270.

- ^Fu, Q.; Meyer, M.; Gao, X.; et al. (2013)."DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.110(6): 2223–2227.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.2223F.doi:10.1073/pnas.1221359110.PMC3568306.PMID23341637.

- ^Carlhoff, Selina (2021)."Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallace".Nature.596(7873): 543–547.Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C.doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6.PMC8387238.PMID34433944.

- ^Abi-Rached, L.; Jobin, M. J.; Kulkarni, S.; McWhinnie, A.; et al. (2011)."The Shaping of Modern Human Immune Systems by Multiregional Admixture with Archaic Humans".Science.334(6052): 89–94.Bibcode:2011Sci...334...89A.doi:10.1126/science.1209202.PMC3677943.PMID21868630.

- ^Sankararaman, S.; Mallick, S.; Patterson, N.; Reich, D. (2016)."The combined landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans".Current Biology.26(9): 1241–1247.Bibcode:2016CBio...26.1241S.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.037.PMC4864120.PMID27032491.

- ^Muscat, Baron Y. (2021)."Could the Denisovan Genes have conferred enhanced Immunity Against the G614 Mutation of SARS-CoV-2?".Human Evolution.36.Archived(PDF)from the original on 19 July 2021.Retrieved19 July2021.

- ^Vespasiani, Davide M.; Jacobs, Guy S.; Cook, Laura E.; Brucato, Nicolas; Leavesley, Matthew; Kinipi, Christopher; Ricaut, François-Xavier; Cox, Murray P.; Gallego Romero, Irene (8 December 2022)."Denisovan introgression has shaped the immune system of present-day Papuans".PLOS Genetics.18(12): e1010470.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1010470.ISSN1553-7390.PMC9731433.PMID36480515.

- ^Zimmer, Carl(14 December 2023)."Morning Person? You Might Have Neanderthal Genes to Thank. - Hundreds of genetic variants carried by Neanderthals and Denisovans are shared by people who like to get up early".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2023.Retrieved14 December2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Karlsson, Mattis.From Fossil To Fact: The Denisova Discovery as Science in Action(Thesis). LiU E-press.ISBN9789179291716.Retrieved18 March2022.

External links

[edit] Media related toDenisovaat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toDenisovaat Wikimedia Commons- The Denisova Consortium's raw sequence data and alignments

- Human Timeline (Interactive)–Smithsonian,National Museum of Natural History(August 2016).

- Picture of Denisovan molar.