Dennis Gabor

Dennis Gabor | |

|---|---|

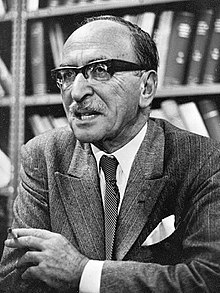

Gabor,c.1971 | |

| Born | Dénes Günszberg 5 June 1900 |

| Died | 9 February 1979(aged 78) London, England |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Spouse |

Marjorie Louise Butler

(m.1936) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students | |

Dennis GaborCBEFRS[1](/ˈɡɑːbɔːr,ɡəˈbɔːr/GAH-bor, gə-BOR;[3][4][5][6]Hungarian:Gábor Dénes,pronounced[ˈɡaːborˈdeːnɛʃ];5 June 1900 – 9 February 1979) was a Hungarian-Britishelectrical engineerandphysicistwho inventedholography,for which he received the 1971Nobel Prize in Physics.[7][8][9][10][11][12]He obtained British citizenship in 1934 and spent most of his life in England.[13][14]

Life and career[edit]

Gabor was born asGünszberg Dénes,into a Jewish family inBudapest,Hungary. In 1900, his family converted toLutheranism.[15]Dennis was the first-born son of Günszberg Bernát and Jakobovits Adél. Despite having a religious background, religion played a minor role in his later life and he considered himself agnostic.[16]In 1902, the family received permission to change their surname from Günszberg to Gábor. He served with the Hungarian artillery in northern Italy duringWorld War I.[17]

He began his studies in engineering at theBudapest University of Technology and Economicsin 1918, later in Germany, at theTechnische Hochschule CharlottenburginBerlin,now known asTechnische Universität Berlin.[18]At the start of his career, he analysed the properties of high voltage electric transmission lines by using cathode-beam oscillographs, which led to his interest in electron optics.[18]Studying the fundamental processes of theoscillograph,Gabor was led to other electron-beam devices such aselectron microscopesand TV tubes. He eventually wrote his PhD thesis on Recording of Transients in Electric Circuits with the Cathode Ray Oscillograph in 1927, and worked onplasma lamps.[18]

In 1933 Gabor fled fromNazi Germany,where he was considered Jewish, and was invited toBritainto work at the development department of theBritish Thomson-Houstoncompany inRugby, Warwickshire.During his time in Rugby, he met Marjorie Louise Butler, and they married in 1936. He became aBritish citizenin 1946,[19]and it was while working at British Thomson-Houston in 1947 that he invented holography, based on anelectron microscope,and thus electrons instead of visible light.[20]He experimented with a heavily filteredmercury arc light source.[18]The earliest visual hologram was only realised in 1964 following the 1960 invention of thelaser,the firstcoherentlight source. After this, holography became commercially available.

Gabor's research focused on electron inputs and outputs, which led him to the invention of holography.[18]The basic idea was that for perfect optical imaging, the total of all the information has to be used; not only the amplitude, as in usual optical imaging, but also the phase. In this manner, a complete holo-spatial picture can be obtained.[18]Gabor published his theories of holography in a series of papers between 1946 and 1951.[18]

Gabor also researched how human beings communicate and hear; the result of his investigations was the theory ofgranular synthesis,althoughGreekcomposerIannis Xenakisclaimed that he was actually the first inventor of this synthesis technique.[21]Gabor's work in this and related areas was foundational in the development oftime–frequency analysis.

In 1948 Gabor moved from Rugby toImperial College London,and in 1958 became professor ofApplied Physicsuntil his retirement in 1967. His inaugural lecture on 3 March 1959, 'Electronic Inventions and their Impact on Civilisation' provided inspiration forNorbert Wiener's treatment of self-reproducing machines in the penultimate chapter in the 1961 edition of his bookCybernetics.

As part of his many developments related to CRTs, in 1958 Gabor patented a newflat screen televisionconcept. This used anelectron gunaimed perpendicular to the screen, rather than straight at it. The beam was then directed forward to the screen using a series of fine metal wires on either side of the beam path. The concept was significantly similar to theAiken tube,introduced in the US the same year. This led to a many-yearspatent battlewhich resulted in Aiken keeping the US rights and Gabor the UK. Gabor's version was later picked up byClive Sinclairin the 1970s, and became a decades-long quest to introduce the concept commercially. Its difficult manufacturing, due to the many wires within the vacuum tube, meant this was never successful. While looking for a company willing to try to manufacture it, Sinclair began negotiations withTimex,who instead took over production of theZX81.[22]

In 1963 Gabor publishedInventing the Futurewhich discussed the three major threats Gabor saw to modern society: war, overpopulation and the Age of Leisure. The book contained the now well-known expression that "the future cannot be predicted, but futures can be invented." ReviewerNigel Calderdescribed his concept as, "His basic approach is that we cannot predict the future, but we can invent it..." Others such asAlan Kay,Peter Drucker,andForrest Shakleehave used various forms of similar quotes.[23]His next book,Innovations: scientific, technological, and socialwhich was published in 1970, expanded on some of the topics he had already earlier touched upon, and also pointed to his interest in technological innovation as mechanism of both liberation and destruction.

In 1971 he was the single recipient of theNobel Prize in Physicswith the motivation "for his invention and development of the holographic method"[24]and presented the history of the development of holography from 1948 in his Nobel lecture.

While spending much of his retirement in Italy atLavinioRome, he remained connected with Imperial College as a senior research fellow and also became staff scientist ofCBS Laboratories,inStamford, Connecticut;there, he collaborated with his lifelong friend, CBS Labs' presidentDr. Peter C. Goldmarkin many new schemes of communication and display. One of Imperial College's new halls of residence in Prince's Gardens,Knightsbridgeis named Gabor Hall in honour of Gabor's contribution to Imperial College. He developed an interest in social analysis and publishedThe Mature Society: a view of the futurein 1972.[25]He also joined theClub of Romeand supervised a working group studying energy sources and technical change. The findings of this group were published in the reportBeyond the Age of Wastein 1978, a report which was an early warning of several issues that only later received widespread attention.[26]

Following the rapid development of lasers and a wide variety of holographic applications (e.g., art, information storage, and the recognition of patterns), Gabor achieved acknowledged success and worldwide attention during his lifetime.[18]He received numerous awards besides the Nobel Prize.

Gabor died in a nursing home inSouth Kensington,London, on 9 February 1979. In 2006 ablue plaquewas put up on No. 79Queen's GateinKensington,where he lived from 1949 until the early 1960s.[27]

Personal life[edit]

On 8 August 1936, he married Marjorie Louise Butler. They did not have any children.

Publications[edit]

- The Electron Microscope (1934)

- Inventing the Future (1963)

- Innovations: Scientific, Technological, and Social (1970)

- The Mature Society (1972)

- Proper Priorities of Science and Technology (1972)

- Beyond the Age of Waste: A Report to the Club of Rome (1979, with U. Colombo, A. King en R. Galli)

Awards and honors[edit]

- 1956 – Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS)[1]

- 1964 – Honorary Member of theHungarian Academy of Sciences

- 1964 –D.Sc.,University of London

- 1967 –Young Medal and Prize,for distinguished research in the field ofoptics

- 1967 – Columbus Award of the International Institute for Communications,Genoa

- 1968 – The firstAlbert A. Michelson Medalfrom TheFranklin Institute,Philadelphia[28]

- 1968 –Rumford Medalof the Royal Society

- 1970 –Honorary Doctorate,University of Southampton

- 1970 –Medal of Honorof theInstitute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

- 1970 – Commander of theOrder of the British Empire(CBE)

- 1971 –Nobel Prize in Physics,for his invention and development of the holographic method

- 1971 –Honorary Doctorate,Delft University of Technology

- 1972 –Holweck Prizeof the Société Française de Physique

- 1983 – theInternational Society for Optical Engineering(SPIE) established the annualDennis Gabor Award,"in recognition of outstanding accomplishments in diffractive wavefront technologies, especially those which further the development of holography andmetrologyapplications. "[29]

- 1989 – theRoyal Society of Londonbegan issuing theGabor Medalfor "acknowledged distinction of interdisciplinary work between the life sciences with other disciplines".[30]

- 1992 –Gábor Dénes CollegeinBudapest,Hungary,is named after Gabor.

- 1993 – theNOVOFER Foundationof theHungarian Academy of Sciencesestablished its annualInternational Dennis Gabor Award,for outstanding young scientists researching in the fields of physics and applied technology.

- 2000 – the asteroid72071 Gáboris named after Gabor.

- 2008 – theInstitute of Physicsrenamed its Duddell Medal and Prize, established in 1923, into theDennis Gabor Medal and Prize.

- 2009 – Imperial College London opened the Gabor Hall.[31]

- Dennis-Gabor-Straße inPotsdamis named in his honour and is the location of the Potsdamer Centrum für Technologie.

In popular culture[edit]

- TheGabor familyfrom the animated TV seriesJem and The Hologramswas named after Dennis Gabor.

- On 5 June 2010, the logo for theGooglewebsite was drawn to resemble a hologram in honour of Dennis Gabor's 110th birthday.[32]

- InDavid Foster Wallace'sInfinite Jest,Hal suggests that "Dennis Gabor may very well have been the Antichrist."[33]

See also[edit]

- Adaptive Gabor representation

- Gabor expansion

- Gabor frame

- Microsound

- Meniscus corrector

- Gábor Dénes College

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

References[edit]

- ^abcAllibone, T. E. (1980). "Dennis Gabor. 5 June 1900 – 9 February 1979".Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society.26:106.doi:10.1098/rsbm.1980.0004.S2CID53732181.

- ^Shewchuck, S. (December 1952)."SUMMARY OF RESEARCH PROGRESS MEETINGS OF OCT. 16, 23 AND 30, 1952".Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory:3.

- ^"Gabor".The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language(5th ed.). HarperCollins.Retrieved26 July2019.

- ^"Gabor".Collins English Dictionary.HarperCollins.Retrieved26 July2019.

- ^"Gabor, Dennis".LexicoUK English Dictionary.Oxford University Press.Archived fromthe originalon 25 June 2021.

- ^"Gabor".Merriam-Webster Dictionary.Retrieved26 July2019.

- ^Ash, Eric A. (1979)."Dennis Gabor, 1900–1979".Nature.280(5721): 431–433.Bibcode:1979Natur.280..431A.doi:10.1038/280431a0.PMID379651.

- ^Gabor, Dennis (1944).The electron microscope: Its development, present performance and future possibilities.London.[ISBN missing]

- ^Gabor, Dennis (1963).Inventing the Future.London: Secker & Warburg.[ISBN missing]

- ^Gabor, Dennis (1970).Innovations: Scientific, Technological, and Social.London: Oxford University Press.[ISBN missing]

- ^Gabor, Dennis (1972).The Mature Society. A View of the Future.London: Secker & Warburg.[ISBN missing]

- ^Gabor, Dennis; and Colombo, Umberto (1978).Beyond the Age of Waste: A Report to the Club of Rome.Oxford: Pergamon Press.[ISBN missing]

- ^"GÁBOR DÉNES".sztnh.gov.hu(in Hungarian). Szellemi Tulajdon Nemzeti Hivatala. 25 April 2016.Retrieved19 July2021.

- ^"Gábor Dénes".itf.njszt.hu(in Hungarian). Neumann János Számítógép-tudományi Társaság. 28 August 2019.Retrieved19 July2021.

- ^Dennis Gabor Biography.Bookrags (2 November 2010). Retrieved on 7 September 2017.

- ^Brigham Narins (2001).Notable Scientists from 1900 to the Present: D-H.Gale Group. p.797.ISBN978-0-7876-1753-0.

Although Gabor's family became Lutherans in 1918, religion appeared to play a minor role in his life. He maintained his church affiliation through his adult years but characterized himself as a "benevolent agnostic".

- ^Johnston, Sean (2006)."Wavefront Reconstruction and beyond".Holographic Visions.OUP Oxford. p. 17.ISBN978-0-19-857122-3.

- ^abcdefghBor, Zsolt(1999)."Optics by Hungarians".Fizikai Szemle.5:202.Bibcode:1999AcHA....5..202Z.ISSN0015-3257.Retrieved5 June2010.

- ^Wasson, Tyler; Brieger, Gert H. (1987).Nobel Prize Winners: An H. W. Wilson Biographical Dictionary.H. W. Wilson. p. 359.ISBN0-8242-0756-4.

- ^GB685286 GB patent GB685286,British Thomson-Houston Company,published 1947

- ^Xenakis, Iannis (2001).Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition.Vol. 9th (2nd ed.). Pendragon Pr. pp. preface xiii.ISBN1-57647-079-2.

- ^Adamson, Ian; Kennedy, Richard (1986).Sinclair and the 'sunrise' Technology.Penguin. pp. 91–92.

- ^"We Cannot Predict the Future, But We Can Invent It".quoteinvestigator. 27 September 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 26 December 2013.Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^"The Nobel Prize in Physics 1971".nobelprize.org.

- ^IEEE Global History Network (2011)."Dennis Gabor".IEEE History Center.Retrieved14 July2011.

- ^Gabor, Dennis; Colombo, Umberto; King, Alexander; Galli, Riccardo (1978).Club of Rome: Beyond the Age of Waste.Pergamon Press.ISBN0-08-021834-2.

- ^"Blue Plaque for Dennis Gabor, inventor of Holograms".Government News. 1 June 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2013.Retrieved23 November2013.

- ^"Franklin Laureate Database – Albert A. Michelson Medal Laureates".Franklin Institute.Archived fromthe originalon 6 April 2012.Retrieved14 June2011.

- ^"Dennis Gabor Award".SPIE.2010. Archived fromthe originalon 25 October 2015.Retrieved4 June2010.

- ^"The Gabor Medal (1989)".Royal Society.2009.Retrieved4 June2010.

- ^Eastside Halls.imperial.ac.uk

- ^"Dennis Gabor's birth celebrated by Google doodle".The Telegraph.London. 5 June 2010.Retrieved5 June2010.

- ^Wallace, David Foster (1996)."Infinite Jest".New York: Little, Brown and Co.: 12.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links[edit]

- Dennis Gaboron Nobelprize.orgincluding the Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1970Magnetism and the Local Molecular Field

- Nobel Prize presentation speechby Professor Erik Ingelstam of theRoyal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Biographyat theWayback Machine(archived 27 July 2008)

- Works by or about Dennis GaboratInternet Archive

- 1900 births

- 1979 deaths

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- British Nobel laureates

- Hungarian Nobel laureates

- Nobel laureates from Austria-Hungary

- Academics of Imperial College London

- Technische Universität Berlin alumni

- Academic staff of Technische Universität Berlin

- British agnostics

- British electrical engineers

- 20th-century British inventors

- British Lutherans

- British Jews

- 20th-century British physicists

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Futurologists

- Hungarian agnostics

- Hungarian electrical engineers

- Hungarian emigrants to England

- 20th-century Hungarian inventors

- Hungarian Jews

- Hungarian refugees

- 20th-century Hungarian physicists

- Members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

- IEEE Medal of Honor recipients

- Jews who immigrated to the United Kingdom to escape Nazism

- Jewish agnostics

- Jewish engineers

- Jewish physicists

- People from Pest, Hungary

- Hungarian emigrants to Germany

- Converts to Christianity from Judaism

- Optical engineers