Dire wolf

| Dire wolf Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton,Sternberg Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Subfamily: | Caninae |

| Tribe: | Canini |

| Subtribe: | Canina |

| Genus: | †Aenocyon Merriam,1918[2] |

| Species: | †A. dirus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Aenocyon dirus | |

| Subspecies[3] | |

| Synonyms | |

Thedire wolf(Aenocyon dirus[10]/iːˈnɒsaɪ.ɒnˈdaɪrəs/) is an extinctcanine.The dire wolf lived in theAmericas(with a possible single record also known fromEast Asia) during theLate Pleistoceneand EarlyHoloceneepochs (125,000–9,500 years ago). The species was named in 1858, four years after the first specimen had been found. Twosubspeciesare recognized:Aenocyon dirus guildayiandAenocyon dirus dirus.The largest collection of itsfossilshas been obtained from the RanchoLa Brea Tar PitsinLos Angeles.

Dire wolf remains have been found across a broad range of habitats including the plains, grasslands, and some forested mountain areas of North America, the arid savanna of South America. The sites range in elevation from sea level to 2,255 meters (7,400 ft). Dire wolf fossils have rarely been found north of42°N latitude;there have been only five unconfirmed reports above this latitude. This range restriction is thought to be due to temperature, prey, or habitat limitations imposed by proximity to theLaurentideandCordilleranice sheets that existed at the time.

The dire wolf was about the same size as the largest moderngray wolves(Canis lupus): theYukon wolfand thenorthwestern wolf.A.d.guildayiweighed on average 60 kilograms (132 lb) andA.d.diruswas on average 68 kg (150 lb). Its skull and dentition matched those ofC.lupus,but its teeth were larger with greater shearing ability, and its bite force at thecanine toothwas stronger than any knownCanisspecies. These characteristics are thought to be adaptations for preying on Late Pleistocenemegaherbivores,and in North America, its prey is known to have includedwestern horses,ground sloths,mastodons,ancient bison,andcamels.Its extinction occurred during theQuaternary extinction eventalong with its main prey species. Its reliance on megaherbivores has been proposed as the cause of its extinction, along withclimatic changeandcompetitionwith other species, or a combination of those factors. Dire wolves lived as recently as 9,500 years ago, according to dated remains.

Taxonomy

[edit]From the 1850s, the fossil remains of extinct large wolves were being found in the United States, and it was not immediately clear that these all belonged to one species. The first specimen of what would later become associated withAenocyon diruswas found in mid-1854 in the bed of theOhio RivernearEvansville, Indiana.The fossilized jawbone with cheek teeth was obtained by the geologistJoseph Granville Norwoodfrom an Evansville collector, Francis A. Linck. The paleontologistJoseph Leidydetermined that the specimen represented an extinct species of wolf and reported it under the name ofCanis primaevus.[4]Norwood's letters to Leidy are preserved along with thetype specimen(the first of a species that has a written description) at theAcademy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.In 1857, while exploring theNiobrara Rivervalley in Nebraska, Leidy found the vertebrae of an extinctCanisspecies that he reported the following year under the nameC.dirus.[1]The nameC.primaevus(Leidy 1854) was later renamedCanis indianensis(Leidy 1869) when Leidy found out that the nameC.primaevushad previously been used by the British naturalistBrian Houghton Hodgsonfor thedhole.[5]

In 1876 the zoologistJoel Asaph Allendiscovered the remains ofCanis mississippiensis(Allen 1876) and associated these withC.dirus(Leidy 1858) andCanis indianensis(Leidy 1869). As so little was found of these three specimens, Allen thought it best to leave each specimen listed under its provisional name until more material could be found to reveal their relationship.[6]In 1908 the paleontologistJohn Campbell Merriambegan retrieving numerous fossilized bone fragments of a large wolf from the Rancho LaBrea tar pits. By 1912 he had found a skeleton sufficiently complete to be able to formally recognize these and the previously found specimens under the nameC.dirus(Leidy 1858). Because the rules ofnomenclaturestipulated that the name of a species should be the oldest name ever applied to it,[12]Merriam therefore selected the name of Leidy's 1858 specimen,C.dirus.[13]In 1915 the paleontologist Edward Troxell indicated his agreement with Merriam when he declaredC.indianensisa synonym ofC.dirus.[14]In 1918, after studying these fossils, Merriam proposed consolidating their names under the separate genusAenocyon(fromainos,'terrible' andcyon,'dog') to becomeAenocyon dirus,[2]but at that time not everyone agreed with this extinct wolf being placed in a new genus separate from the genusCanis.[15]Canis ayersi(Sellards 1916) andAenocyon dirus(Merriam 1918) were recognized as synonyms ofC.dirusby the paleontologistErnest Lundeliusin 1972.[16]All of the above taxa were declared synonyms ofC.dirusin 1979, according to the paleontologist Ronald M. Nowak.[17]

In 1984 a study byBjörn Kurténrecognized a geographic variation within the dire wolf populations and proposed two subspecies:Canis dirus guildayi(named by Kurtén in honor of the paleontologist John E. Guilday) for specimens from California and Mexico that exhibited shorter limbs and longer teeth, andCanis dirus dirusfor specimens east of the North AmericanContinental Dividethat exhibited longer limbs and shorter teeth.[3][18][19][20]Kurtén designated amaxillafound in Hermit's Cave, New Mexico as representing the nominate subspeciesC. d. dirus.[3]

In 2021, a DNA study found the dire wolf to be a highlydivergentlineage when compared with the extantwolf-like canines,and this finding is consistent with the previously proposed taxonomic classification of the dire wolf as genusAenocyon(Ancient Greek: "terrible wolf" ) as proposed by Merriam in 1918.[21]

Evolution

[edit]In North America, thecanidfamily came into existence 40 million years ago,[22][23]and the canine subfamilyCaninaeabout 32 million years ago.[24]From the Caninae, the ancestors of the fox-likeVulpiniand the dog-likeCaninicame into existence 9 million years ago. This group was first represented byEucyon,and mostly bycoyote-likeEucyon davisithat was spread widely across North America.[25]From the Canini theCerdocyonina,today represented by the South American canids, came into existence 6–5 million years ago.[26]Its sister the wolf-likeCaninacame into existence 5 million years ago, however, they are likely to have originated as far back as 9 million years ago.[25]Around 7 million years ago, the canines expanded into Eurasia and Africa, withEucyongiving rise to the first of the genusCanisin Europe.[27]Around 4–3 million years agoC. chihliensis,the first wolf-sized member ofCanis,arose in China and expanded to give rise to other wolf-like members across Eurasia and Africa. Members of the genusCaniswould later expand into North America.[26]

The dire wolf evolved in North America.[26][21]However, its ancestral lineage is debated, with two competing theories. The first theory is based on fossilmorphology,which indicates that an expansion of the genusCanisout of Eurasia led to the dire wolf.[26]The second theory is based on DNA evidence, which indicates that the dire wolf arose from an ancestral lineage that originated in the Americas and was separate from the genusCanis.[21]

Morphological evidence

[edit]| Dire wolf divergence based on morphology | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Evolutionary divergenceof the dire wolf based on morphology[26][28] |

Morphological evidence based on fossil remains indicates an expansion of genusCanisfrom out of Eurasia led to the dire wolf.[26][28]

In 1974 Robert A. Martin proposed that the large North American wolfC. armbrusteri(Armbruster's wolf) wasC. lupus.[29]Nowak, Kurtén, andAnnalisa Bertaproposed thatC. diruswas not derived fromC. lupus.[17][30][31]In 1987, a new hypothesis proposed that a mammal population could give rise to a larger form called a hypermorph during times when food was abundant, but when food later became scarce the hypermorph would either adapt to a smaller form or go extinct. This hypothesis might explain the large body sizes found in many Late Pleistocene mammals compared to their modern counterparts. Both extinction andspeciation– a process by which a new species splits from an older one – could occur together during periods of climatic extremes.[32][33]Gloria D. Goulet agreed with Martin, proposing further that this hypothesis might explain the sudden appearance ofC. dirusin North America and, judging from the similarities in their skull shapes, thatC. lupushad given rise to theC. dirushypermorph due to an abundance of game, a stable environment, and large competitors.[34]

The three paleontologistsXiaoming Wang,Richard H. Tedford,and Ronald M. Nowak propose thatC. dirusevolved fromCanis armbrusteri,[26][28]with Nowak stating that both species arose in the Americas[35]and that specimens found inCumberland Cave, Maryland,appear to beC. armbrusteridiverging intoC. dirus.[36][37]Nowak believed thatCanis edwardiiwas the first appearance of the wolf in North America, and it appears to be close to the lineage which producedC. armbrusteriandC. dirus.[38]Tedford believes that the early wolf from China,Canis chihliensis,may have been the ancestor of bothC. armbrusteriand thegray wolfC. lupus.[39]The sudden appearance ofC. armbrusteriin mid-latitude North America during theEarly Pleistocene1.5 million years ago, along with the mammoth, suggests that it was an immigrant from Asia,[28]with the gray wolfC. lupusevolving in Beringia later in thePleistoceneand entering mid-latitude North America during theLast Glacial Periodalong with its Beringian prey.[26][28][37]In 2010 Francisco Prevosti proposed thatC. diruswas asister taxontoC. lupus.[40]

C. diruslived in the Late Pleistocene to the earlyHolocene,125,000–10,000YBP(years before present), in North and South America.[3]The majority of fossils from the easternC. d. dirushave been dated 125,000–75,000 YBP, but the westernC. d. guildayifossils are not only smaller in size but more recent; thus it has been proposed thatC. d. guildayiderived fromC. d. dirus.[3][20]However, there are disputed specimens ofC. dirusthat date to 250,000 YBP. Fossil specimens ofC. dirusdiscovered at four sites in theHay Springsarea ofSheridan County, Nebraska,were namedAenocyon dirus nebrascensis(Frick 1930, undescribed), but Frick did not publish a description of them. Nowak later referred to this material asC. armbrusteri;[41]then, in 2009, Tedford formally published a description of the specimens and noted that, although they exhibited some morphological characteristics of bothC. armbrusteriandC. dirus,he referred to them only asC. dirus.[39]

A fossil discovered in the Horse Room of the Salamander Cave in theBlack Hillsof South Dakota may possibly beC. dirus;if so, this fossil is one of the earliest specimens on record.[19][42]It was catalogued asCanis cf. C. dirus[43](wherecf.in Latin means confer, uncertain). The fossil of a horse found in the Horse Room provided auranium-series datingof 252,000YBPand theCanis cf. dirusspecimen was assumed to be from the same period.[19][43]C. armbrusteriandC. dirusshare some characteristics (synapomorphies) that imply the latter's descent from the former. The fossil record suggestsC. dirusoriginated around 250,000 YBP in the open terrain of the mid-continent before expanding eastward and displacing its ancestorC. armbrusteri.[28]The first appearance ofC. diruswould therefore be 250,000 YBP in California and Nebraska, and later in the rest of the United States, Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru,[39]but the identity of these earliest fossils is not confirmed.[44]

In South America,C. dirusspecimens dated to the Late Pleistocene were found along the north and west coasts, but none have been found in Argentina, an area that was inhabited byCanis geziandCanis nehringi.[39]Given their similarities and timeframes, it is proposed thatC. geziwas the ancestor ofCanis nehringi.One study found thatC. diruswas moreevolutionarily derivedcompared withC. nehringi,and was larger in the size and construction of its lower molars for more efficient predation.[45]For this reason, some researchers have proposed thatC. dirusmay have originated in South America.[46][19][31]Tedford proposed thatC. armbrusteriwas the common ancestor for both the North and South American wolves.[39]Later studies concluded thatC. dirusandC. nehringiwere the same species,[40][47]and thatC. dirushad migrated from North America into South America, making it a participant in theGreat American Interchange.[40]In 2018, a study found thatCanis gezidid not fall under genusCanisand should be classified under the subtribeCerdocyonina,however no genus was proposed.[47]

The 2020 discovery of a claimed dire wolf fossil in northeast China indicates that dire wolves may have crossedBeringiawhen it existed.[48]

DNA evidence

[edit]| Cladogramshowing relationships among living and extinct wolf-like canids based on DNA[note 1] |

| Based onnDNAdata indicating that the dire wolf branched 5.7 million years ago[21] |

DNA evidence indicates the dire wolf arose from an ancestral lineage that originated in the Americas and was separate to genusCanis.[21]

In 1992 an attempt was made to extract amitochondrial DNAsequence from the skeletal remains ofA.d.guildayito compare its relationship to otherCanisspecies. The attempt was unsuccessful because these remains had been removed from the LaBrea pits and tar could not be removed from the bone material.[51]In 2014 an attempt to extract DNA from aColumbian mammothfrom the tar pits also failed, with the study concluding that organic compounds from the asphalt permeate the bones of all ancient samples from the LaBrea pits, hindering the extraction of DNA samples.[52]

In 2021, researchers sequenced thenuclear DNA(from the cell nucleus) taken from five dire wolf fossils dating from 13,000 to 50,000 years ago. The sequences indicate the dire wolf to be a highly divergent lineage which last shared amost recent common ancestorwith the wolf-like canines 5.7 million years ago. The study also measured numerous dire wolf and gray wolf skeletal samples that showed their morphologies to be highly similar, which had led to the theory that the dire wolf and the gray wolf had a close evolutionary relationship. The morphological similarity between dire wolves and gray wolves was concluded to be due toconvergent evolution.Members of the wolf-like canines are known to hybridize with each other but the study could find no indication ofgenetic admixturefrom the five dire wolf samples with extant North American gray wolves and coyotes nor their common ancestor. This finding indicates that the wolf and coyote lineages evolved in isolation from the dire wolf lineage.[21]

The study proposes an early origin of the dire wolf lineage in the Americas, and that this geographic isolation allowed them to develop a degree ofreproductive isolationsince their divergence 5.7 million years ago. Coyotes, dholes, gray wolves, and the extinctXenocyonevolved in Eurasia and expanded into North America relatively recently during the Late Pleistocene, therefore there was no admixture with the dire wolf. The long-term isolation of the dire wolf lineage implies that other American fossil taxa, includingC. armbrusteriandC. edwardii,may also belong to the dire wolf's lineage. The study's findings are consistent with the previously proposed taxonomic classification of the dire wolf as genusAenocyon.[21]

Radiocarbon dating

[edit]The age of most dire wolf localities is determined solely bybiostratigraphy,but biostratigraphy is an unreliable indicator within asphalt deposits.[53][54]Some sites have beenradiocarbon dated,with dire wolf specimens from the LaBrea pits dated in calendar years as follows: 82 specimens dated 13,000–14,000YBP; 40 specimens dated 14,000–16,000YBP; 77 specimens dated 14,000–18,000YBP; 37 specimens dated 17,000–18,000YBP; 26 specimens dated 21,000–30,000YBP; 40 specimens dated 25,000–28,000YBP; and 6specimens dated 32,000–37,000YBP.[44]: T1 A specimen from Powder Mill Creek Cave, Missouri, was dated at 13,170YBP.[19]

Description

[edit]

The average dire wolf proportions were similar to those of two modern North American wolves: theYukon wolf(Canis lupus pambasileus)[55][13]and theNorthwestern wolf(Canis lupus occidentalis).[55]The largest northern wolves today have a shoulder height of up to 38 in (97 cm) and a body length of 69 in (180 cm).[56]: 1 Some dire wolf specimens from Rancho LaBrea are smaller than this, and some are larger.[13]

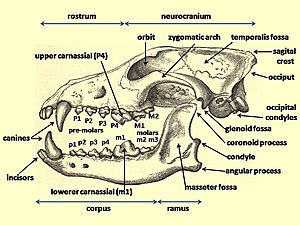

The dire wolf had smaller feet and a larger head when compared with a northern wolf of the same body size. The skull length could reach up to 310 mm (12 in) or longer, with a broaderpalate,frontal region,andzygomatic archescompared with the Yukon wolf. These dimensions make the skull very massive. Itssagittal crestwas higher, with theinionshowing a significant backward projection, and with the rear ends of thenasal bonesextending relatively far back into the skull. A connected skeleton of a dire wolf from Rancho LaBrea is difficult to find because the tar allows the bones to disassemble in many directions. Parts of avertebral columnhave been assembled, and it was found to be similar to that of the modern wolf, with the same number of vertebrae.[13]

Geographic differences in dire wolves were not detected until 1984, when a study of skeletal remains showed differences in a few cranio-dental features and limb proportions between specimens from California and Mexico (A.d.guildayi) and those found from the east of theContinental Divide(A.d.dirus). A comparison of limb size shows that the rear limbs ofA.d.guildayiwere 8% shorter than the Yukon wolf due to a significantly shortertibiaandmetatarsus,and that the front limbs were also shorter due to their slightly shorter lower bones.[57][58]With its comparatively lighter and smaller limbs and massive head,A.d.guildayiwas not as well adapted for running as timber wolves and coyotes.[58][13]A.d.diruspossessed significantly longer limbs thanA.d.guildayi.The forelimbs were 14% longer thanA.d.guildayidue to 10% longerhumeri,15% longerradii,and 15% longermetacarpals.The rear limbs were 10% longer thanA.d.guildayidue to 10% longerfemoraand tibiae, and 15% longermetatarsals.A.d.dirusis comparable to the Yukon wolf in limb length.[57]The largestA.d.dirusfemur was found in Carroll Cave, Missouri, and measured 278 mm (10.9 in).[20]

| Limb variable | A. d. guildayi[58] | Yukon wolf[58] | A. d. dirus[57] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humerus (upper front leg) | 218 mm (8.6 in) | 237 mm (9.3 in) | 240 mm (9.4 in) |

| Radius (lower front leg) | 209 mm (8.2 in) | 232 mm (9.1 in) | 240 mm (9.4 in) |

| Metacarpal (front foot) | 88 mm (3.4 in) | 101 mm (4.0 in) | 101 mm (4.0 in) |

| Femur (upper back leg) | 242 mm (9.5 in) | 251 mm (9.9 in) | 266 mm (10.5 in) |

| Tibia (lower back leg) | 232 mm (9.1 in) | 258 mm (10.2 in) | 255 mm (10.0 in) |

| Metatarsal (back foot) | 93 mm (3.7 in) | 109 mm (4.3 in) | 107 mm (4.2 in) |

A.d.guildayiis estimated to have weighed on average 60 kg (132 lb), andA.d.dirusweighed on average 68 kg (150 lb) with some specimens being larger,[20]but these could not have exceeded 110 kg (243 lb) due to skeletal limits.[59]In comparison, the average weight of the Yukon wolf is 43 kg (95 lb) for males and 37 kg (82 lb) for females. Individual weights for Yukon wolves can vary from 21 kg (46 lb) to 55 kg (121 lb),[60]with one Yukon wolf weighing 79.4 kg (175 lb).[56]: 1 These figures show the average dire wolf to be similar in size to the largest modern gray wolf.[20]

The remains of a complete maleA. dirusare sometimes easy to identify compared to otherCanisspecimens because thebaculum(penis bone) of the dire wolf is very different from that of all other livingcanids.[19][57]

Adaptation

[edit]

Ecological factors such as habitat type, climate, prey specialization, and predatory competition have been shown to greatly influence gray wolf craniodentalplasticity,which is an adaptation of thecraniumand teeth due to the influences of the environment.[62][63][64]Similarly, the dire wolf was a hypercarnivore, with a skull and dentition adapted for hunting large and struggling prey;[65][66][67]the shape of its skull and snout changed across time, and changes in the size of its body have been correlated with climate fluctuations.[68]

Paleoecology

[edit]Thelast glacial period,commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000[69]–14,500YBP[70]and was the most recentglacial periodwithin thecurrent ice age,which occurred during the last years of the Pleistocene era.[69]The Ice Age reached its peak during theLast Glacial Maximum,whenice sheetsbegan advancing from 33,000YBP and reached their maximum limits 26,500YBP. Deglaciation commenced in the Northern Hemisphere approximately 19,000YBP and in Antarctica approximately 14,500YBP, which is consistent with evidence that glacial meltwater was the primary source for an abrupt rise in sea level 14,500YBP.[70]Access into northern North America was blocked by theWisconsin glaciation.The fossil evidence from the Americas points to theextinctionmainly of large animals, termedPleistocene megafauna,near the end of the last glaciation.[71]

Coastal southern California from 60,000YBP to the end of the Last Glacial Maximum was cooler and with a more balanced supply of moisture than today. During the Last Glacial Maximum, the mean annual temperature decreased from 11 °C (52 °F) down to 5 °C (41 °F) degrees, and annual precipitation had decreased from 100 cm (39 in) down to 45 cm (18 in).[72]This region was unaffected by the climatic effects of the Wisconsin glaciation and is thought to have been an Ice Agerefugiumfor animals and cold-sensitive plants.[73][74][75]By 24,000YBP, the abundance of oak and chaparral decreased, but pines increased, creating open parklands similar to today's coastalmontane/juniper woodlands. After 14,000YBP, the abundance of conifers decreased, and those of the modern coastal plant communities, including oak woodland, chaparral, andcoastal sage scrub,increased. The Santa Monica Plain lies north of the city ofSanta Monicaand extends along the southern base of theSanta Monica Mountains,and 28,000–26,000YBP it was dominated by coastal sage scrub, with cypress and pines at higher elevations. The Santa Monica Mountains supported a chaparral community on its slopes and isolated coast redwood and dogwood in its protected canyons, along with river communities that included willow, red cedar, and sycamore. These plant communities suggest a winter rainfall similar to that of modern coastal southern California, but the presence of coast redwood now found 600 kilometres (370 mi) to the north indicates a cooler, moister, and less seasonal climate than today. This environment supported large herbivores that were prey for dire wolves and their competitors.[72]

Prey

[edit]

A range of animal and plant specimens that became entrapped and were then preserved in tar pits have been removed and studied so that researchers can learn about the past. The Rancho LaBrea tar pits located near Los Angeles in Southern California are a collection of pits of sticky asphalt deposits that differ in deposition time from 40,000 to 12,000YBP. Commencing 40,000YBP, trapped asphalt has been moved through fissures to the surface by methane pressure, forming seeps that can cover several square meters and be 9–11 m (30–36 ft) deep.[53]A large number of dire wolf fossils have been recovered from the La Brea tar pits.[26]Over 200,000 specimens (mostly fragments) have been recovered from the tar pits,[20]with the remains ranging fromSmilodonto squirrels, invertebrates, and plants.[53]The time period represented in the pits includes the Last Glacial Maximum when global temperatures were 8 °C (14 °F) lower than today, the Pleistocene–Holocene transition (Bølling-Allerødinterval), theOldest Dryascooling, theYounger Dryascooling from 12,800 to 11,500YBP, and the American megafaunal extinction event 12,700YBP when 90 genera of mammals weighing over 44 kg (97 lb) became extinct.[54][68]

Isotope analysiscan be used to identify some chemical elements, allowing researchers to make inferences about the diet of the species found in the pits. Isotope analysis of bonecollagenextracted from LaBrea specimens provides evidence that the dire wolf,Smilodon,and theAmerican lion(Panthera atrox) competed for the same prey. Their prey included"yesterday's camel"(Camelops hesternus), thePleistocene bison(Bison antiquus), the"dwarf" pronghorn(Capromeryx minor), thewestern horse(Equus occidentalis), and the"grazing" ground sloth(Paramylodon harlani) native to North American grasslands. TheColumbian mammoth(Mammuthus columbi) and theAmerican mastodon(Mammut americanum) were rare at LaBrea. The horses remained mixed feeders and the pronghorns mixed browsers, but at the Last Glacial Maximum and its associated shift in vegetation the camels and bison were forced to rely more heavily on conifers.[72]

A study of isotope data of La Brea dire wolf fossils dated 10,000YBP provides evidence that the horse was an important prey species at the time, and that sloth, mastodon, bison, and camel were less common in the dire wolf diet.[65][73]This indicates that the dire wolf was not a prey specialist, and at the close of the Late Pleistocene before its extinction it was hunting or scavenging the most available herbivores.[73]

Dentition and bite force

[edit]

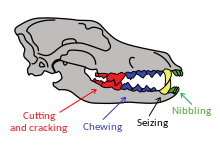

When compared with thedentition of genusCanismembers,the dire wolf was considered the most evolutionary derived (advanced) wolf-like species in the Americas. The dire wolf could be identified separately from all otherCanisspecies by its possession of: "P2 with a posterior cusplet; P3 with two posterior cusplets; M1 with a mestascylid, entocristed, entoconulid, and a transverse crest extending from the metaconid to the hyperconular shelf; M2 with entocristed and entoconulid."[30]

A study of the estimated bite force at the canine teeth of a large sample of living and fossil mammalian predators, when adjusted for the body mass, found that forplacentalmammals the bite force at the canines (innewtons/kilogram of body weight) was greatest in the dire wolf (163), followed among the modern canids by the four hypercarnivores that often prey on animals larger than themselves: theAfrican hunting dog(142), the gray wolf (136), thedhole(112), and thedingo(108). The bite force at the carnassials showed a similar trend to the canines. A predator's largest prey size is strongly influenced by its biomechanical limits. The morphology of the dire wolf was similar to that of its living relatives, and assuming that the dire wolf was a social hunter, then its high bite force relative to living canids suggests that it preyed on relatively large animals. The bite force rating of the bone-consumingspotted hyena(117) challenged the common assumption that high bite force in the canines and the carnassials was necessary to consume bone.[67]

A study of thecranial measurementsand jaw muscles of dire wolves found no significant differences with modern gray wolves in all but 4 of 15 measures. Upper dentition was the same except that the dire wolf had larger dimensions, and the P4 had a relatively larger, more massive blade that enhanced slicing ability at the carnassial. The jaw of the dire wolf had a relatively broader and more massivetemporalismuscle, able to generate slightly more bite force than the gray wolf. Due to the jaw arrangement, the dire wolf had less temporalis leverage than the gray wolf at the lower carnassial (m1) and lower p4, but the functional significance of this is not known. The lower premolars were relatively slightly larger than those of the gray wolf,[66]and the dire wolf m1 was much larger and had more shearing ability.[13][31][66]The dire wolf canines had greater bending strength than those of living canids of equivalent size and were similar to those of hyenas and felids.[78]All these differences indicate that the dire wolf was able to deliver stronger bites than the gray wolf, and with its flexible and more rounded canines was better adapted for struggling with its prey.[65][66]

| Tooth variable | lupusmodern

North American[79] |

lupus La Brea[79] |

lupusBeringia[79] | dirus dirus Sangamonianera[3][65] (125,000–75,000 YBP) |

dirus dirus Late Wisconsin[3][65] (50,000 YBP) |

dirus guildayi[3][65]

(40,000–13,000 YBP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 length | 28.2 | 28.9 | 29.6 | 36.1 | 35.2 | 33.3 |

| m1 width | 10.7 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 14.1 | 13.4 | 13.3 |

| m1trigonidlength | 19.6 | 21.9 | 20.9 | 24.5 | 24.0 | 24.4 |

| p4 length | 15.4 | 16.6 | 16.5 | 16.7 | 16.0 | 19.9 |

| p4 width | - | - | - | 10.1 | 9.6 | 10.3 |

| p2 length | - | - | - | 15.7 | 14.8 | 15.7 |

| p2 width | - | - | - | 7.1 | 6.7 | 7.4 |

Behavior

[edit]At La Brea, predatory birds and mammals were attracted to dead or dying herbivores that had become mired, and then these predators became trapped themselves.[53][80]Herbivore entrapment was estimated to have occurred once every fifty years,[80]and for every instance of herbivore remains found in the pits there were an estimated ten carnivores.[53]A.d.guildayiis the most common carnivoran found at LaBrea, followed bySmilodon.[54][68]Remains of dire wolves outnumber remains of gray wolves in the tar pits by a ratio of five to one.[44]During the Last Glacial Maximum, coastal California, with a climate slightly cooler and wetter than today, is thought to have been a refuge,[73]and a comparison of the frequency of dire wolves and other predator remains at LaBrea to other parts of California and North America indicates significantly greater abundances; therefore, the higher dire wolf numbers in the LaBrea region did not reflect the wider area.[81]Assuming that only a few of the carnivores that were feeding became trapped, it is likely that fairly sizeable groups of dire wolves fed together on these occasions.[82]

The difference between the male and female of a species apart from their sex organs is calledsexual dimorphism,and in this regard little variance exists among the canids. A study of dire wolf remains dated 15,360–14,310YBP and taken from one pit that focused on skull length, canine tooth size, and lower molar length showed little dimorphism, similar to that of the gray wolf, indicating that dire wolves lived in monogamous pairs.[82]Their large size and highly carnivorous dentition supports the proposal that the dire wolf was a predator that fed on large prey.[82][83][84]To kill ungulates larger than themselves, the African wild dog, the dhole, and the gray wolf depend on their jaws as they cannot use their forelimbs to grapple with prey, and they work together as a pack consisting of an Alpha pair and their offspring from the current and previous years. It can be assumed that dire wolves lived in packs of relatives that were led by an Alpha pair.[82]Large and social carnivores would have been successful at defending carcasses of prey trapped in the tar pits from smaller solitary predators, and thus the most likely to become trapped themselves. The manyA.d.guildayiandSmilodonremains found in the tar pits suggests that both were social predators.[81][85]

All social terrestrial mammalian predators prey mostly on terrestrial herbivorous mammals with a body mass similar to the combined mass of the social group members attacking the prey animal.[59][86]The large size of the dire wolf provides an estimated prey size in the 300 to 600 kg (660 to 1,320 lb) range.[20][83][84]Stable isotope analysisof dire wolf bones provides evidence that they had a preference for consumingruminantssuch as bison rather than other herbivores but moved to other prey when food became scarce, and occasionally scavenged on beached whales along the Pacific coast when available.[20][66][87]A pack of timber wolves can bring down a 500 kg (1,100 lb) moose that is their preferred prey,[20][56]: 76 and a pack of dire wolves bringing down a bison is conceivable.[20]Although some studies have suggested that because of tooth breakage, the dire wolf must have gnawed bones and may have been a scavenger, its widespread occurrence and the more gracile limbs of the dire wolf indicate a predator. Like the gray wolf today, the dire wolf probably used its post-carnassial molars to gain access to marrow, but the dire wolf's larger size enabled it to crack larger bones.[66]

Tooth breakage

[edit]

Tooth breakage is related to a carnivore's behavior.[88]A study of nine modern carnivores found that one in four adults had suffered tooth breakage and that half of these breakages were of the canine teeth. The most breakage occurred in the spotted hyena that consumes all of its prey including the bone; the least breakage occurred in theAfrican wild dog,and the gray wolf ranked in between these two.[89][88]The eating of bone increases the risk of accidental fracture due to the relatively high, unpredictable stresses that it creates. The most commonly broken teeth are the canines, followed by the premolars, carnassial molars, and incisors. Canines are the teeth most likely to break because of their shape and function, which subjects them to bending stresses that are unpredictable in both direction and magnitude. The risk of tooth fracture is also higher when killing large prey.[89]

A study of the fossil remains of large carnivores from LaBrea pits dated 36,000–10,000YBP shows tooth breakage rates of 5–17% for the dire wolf, coyote, American lion, andSmilodon,compared to 0.5–2.7% for ten modern predators. These higher fracture rates were across all teeth, but the fracture rates for the canine teeth were the same as in modern carnivores.[clarification needed]The dire wolf broke its incisors more often when compared to the modern gray wolf; thus, it has been proposed that the dire wolf used its incisors more closely to the bone when feeding. Dire wolf fossils from Mexico and Peru show a similar pattern of breakage. A 1993 study proposed that the higher frequency of tooth breakage among Pleistocene carnivores compared with living carnivores was not the result of hunting larger game, something that might be assumed from the larger size of the former. When there is low prey availability, the competition between carnivores increases, causing them to eat faster and thus consume more bone, leading to tooth breakage.[68][88][90]As their prey became extinct around 10,000 years ago, so did these Pleistocene carnivores, except for the coyote (which is anomnivore).[88][90]

A later La Brea pits study compared tooth breakage of dire wolves in two time periods. One pit contained fossil dire wolves dated 15,000YBP and another dated 13,000YBP. The results showed that the 15,000YBP dire wolves had three times more tooth breakage than the 13,000YBP dire wolves, whose breakage matched those of nine modern carnivores. The study concluded that between 15,000 and 14,000YBP prey availability was less or competition was higher for dire wolves and that by 13,000YBP, as the prey species moved towards extinction, predator competition had declined and therefore the frequency of tooth breakage in dire wolves had also declined.[90][91]

Carnivores include bothpack huntersand solitary hunters. The solitary hunter depends on a powerful bite at the canine teeth to subdue their prey, and thus exhibits a strongmandibular symphysis.In contrast, a pack hunter, which delivers many shallower bites, has a comparably weaker mandibular symphysis. Thus, researchers can use the strength of the mandibular symphysis in fossil carnivore specimens to determine what kind of hunter it was – a pack hunter or a solitary hunter – and even how it consumed its prey. The mandibles of canids are buttressed behind the carnassial teeth to enable the animals to crack bones with their post-carnassial teeth (molars M2 and M3). A study found that the mandible buttress profile of the dire wolf was lower than that of the gray wolf and the red wolf, but very similar to the coyote and the African hunting dog. The dorsoventrally weak symphyseal region (in comparison to premolars P3 and P4) of the dire wolf indicates that it delivered shallow bites similar to its modern relatives and was therefore a pack hunter. This suggests that the dire wolf may have processed bone but was not as well adapted for it as was the gray wolf.[92]The fact that the incidence of fracture for the dire wolf reduced in frequency in the Late Pleistocene to that of its modern relatives[88][91]suggests that reduced competition had allowed the dire wolf to return to a feeding behavior involving a lower amount of bone consumption, a behavior for which it was best suited.[90][92]

The results of a study ofdental microwearon tooth enamel for specimens of the carnivore species from LaBrea pits, including dire wolves, suggest that these carnivores were not food-stressed just before their extinction. The evidence also indicated that the extent of carcass utilization (i.e., amount consumed relative to the maximum amount possible to consume, including breakup and consumption of bones) was less than among large carnivores today. These findings indicates that tooth breakage was related to hunting behavior and the size of prey.[93]

Climate impact

[edit]Past studies proposed that changes in dire wolf body size correlated with climate fluctuations.[68][94]A later study compared dire wolf craniodental morphology from four LaBrea pits, each representing four different time periods. The results are evidence of a change in dire wolf size, dental wear and breakage, skull shape, and snout shape across time. Dire wolf body size had decreased between the start of the Last Glacial Maximum and near its ending at the warmAllerød oscillation.Evidence of food stress (food scarcity leading to lower nutrient intake) is seen in smaller body size, skulls with a larger cranial base, and shorter snout (shapeneotenyand size neoteny), and more tooth breakage and wear. Dire wolves dated 17,900YBP showed all of these features, which indicates food stress. Dire wolves dated 28,000YBP also showed to a degree many of these features but were the largest wolves studied, and it was proposed that these wolves were also suffering from food stress and that wolves earlier than this date were even bigger in size.[68]Nutrient stress is likely to lead to stronger bite forces to more fully consume carcasses and to crack bones,[68][95]and with changes to skull shape to improve mechanical advantage. North American climate records reveal cyclic fluctuations during the glacial period that included rapid warming followed by gradual cooling, calledDansgaard–Oeschger events.These cycles would have caused increased temperature and aridity, and at LaBrea would have caused ecological stress and therefore food stress.[68]A similar trend was found with the gray wolf, which in the Santa Barbara basin was originally massive, robust, and possibly convergent evolution with the dire wolf, but was replaced by more gracile forms by the start of the Holocene.[35][34][68]

Dire wolf information based on skull measurements[68] Variable 28,000YBP 26,100 YBP 17,900 YBP 13,800 YBP Body size largest large smallest medium/small Tooth breakage high low high low Tooth wear high low high low Snout shape shortening, largest cranial base average shortest, largest cranial base average Tooth row shape robust – – gracile DOevent number 3 or 4 none imprecise data imprecise data

Competitors

[edit]

Just before the appearance of the dire wolf, North America was invaded by theCanissubgenusXenocyon(ancestor of the Asian dhole and the African hunting dog) that was as large as the dire wolf and more hypercarnivorous. The fossil record shows them as rare, and it is assumed that they could not compete with the newly derived dire wolf.[96]Stable isotope analysis provides evidence that the dire wolf,Smilodon,and the American lion competed for the same prey.[72][93]Other large carnivores included the extinct North American giantshort-faced bear(Arctodus simus), the moderncougar(Puma concolor), thePleistocene coyote(Canis latrans), and the Pleistocene gray wolf that was more massive and robust than today. These predators may have competed with humans who hunted for similar prey.[93]

Specimens that have been identified by morphology asBeringian wolves(C.lupus) and radiocarbon dated 25,800–14,300 YBP have been found in theNatural Trap Caveat the base of theBighorn MountainsinWyoming,in the western United States. The location is directly south of what would at that time have been a division between theLaurentide Ice Sheetand theCordilleran Ice Sheet.A temporary channel between the glaciers may have existed that allowed these large, Alaskan direct competitors of the dire wolf, which were also adapted for preying on megafauna, to come south of the ice sheets. Dire wolf remains are absent north of the 42°Nlatitude in North America, therefore, this region would have been available for Beringian wolves to expand south along the glacier line. How widely they were then distributed is not known. These also became extinct at the end of the Late Pleistocene, as did the dire wolf.[44]

After arriving in easternEurasia,the dire wolf would have likely faced competition from the area's most dominant, widespread predator, the eastern subspecies ofcave hyena(Crocuta crocuta ultima). Competition with this species may have kept Eurasian dire wolf populations very low, leading to the paucity of dire wolf fossil remains in this otherwise well-studied fossil fauna.[97]

Range

[edit]

Dire wolf remains have been found across a broad range of habitats including the plains, grasslands, and some forested mountain areas of North America, the arid savannah of South America, and possibly the steppes of eastern Asia. The sites range in elevation from sea level to 2,255 m (7,400 ft).[19]The location of these fossil remains suggests that dire wolves lived predominantly in the open lowlands along with their prey the large herbivores.[46]Dire wolf remains are not often found at high latitudes in North America.[19]This lack of fossils was used as evidence that the dire wolves did not migrate east via Beringia until the discovery of Asian dire wolf remains in 2020.[97]

In the United States, dire wolf fossils have been reported in Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming,[19]and Nevada.[98]The identity of fossils reported farther north than California is not confirmed.[44]There have been five reports of unconfirmed dire wolf fossils north of 42°Nlatitude atFossil Lake, Oregon(125,000–10,000YBP),American Falls Reservoir, Idaho(125,000–75,000YBP), Salamander Cave, South Dakota (250,000YBP), and four closely grouped sites in northern Nebraska (250,000YBP).[44]This suggests a range restriction on dire wolves due to temperature, prey, or habitat.[44]The major fossil-producing sites forA.d.dirusare located east of theRocky Mountainsand include Friesenhahn Cave, near San Antonio, Texas; Carroll Cave, near Richland, Missouri; andReddick, Florida.[20]

Localities in Mexico where dire wolf remains have been collected include ElCedazo inAguascalientes,Comondú MunicipalityinBaja California Sur,ElCedral inSan Luis Potosí,ElTajo Quarry nearTequixquiac,state of Mexico,Valsequillo inPuebla,Lago de ChapalainJalisco,Loltun CaveinYucatán,Potrecito inSinaloa,San Josecito Cave nearAramberriinNuevo Leónand Térapa inSonora.The specimens from Térapa were confirmed asA.d.guildayi.[65]The finds at San Josecito Cave and ElCedazo have the greatest number of individuals from a single locality.

In South America, dire wolves have been dated younger than 17,000 YBP and have been reported from six localities: Muaco in the westernFalcónstate ofVenezuela,Talara ProvinceinPeru,Monagasstate in easternVenezuela,theTarija DepartmentinBolivia,Atacama DesertofChile,andEcuador.[99][100][19][101]If the dire wolf originated in North America, the species likely dispersed into South America via the Andean corridor,[19][102]a proposed pathway for temperate mammals to migrate from Central to South America because of the favorable cool, dry, and open habitats that characterized the region at times. This most likely happened during a glacial period because the pathway then consisted of open, arid regions and savanna, whereas during inter-glacial periods it would have consisted of tropical rain forest.[19][103]

In 2020, a fossil mandible later analyzed as a dire wolf’s was found in the vicinity ofHarbin,northeastern China. The fossil was taxonomically described and dated 40,000 YBP. This discovery challenges previous theories that the cold temperatures and ice sheets at northern latitudes in North America would be a barrier for dire wolves, which was based on no dire wolf fossils being found above the42° latitudein North America. It is proposed that the dire wolf followed migrating prey from mid-latitude North America then acrossBeringiainto Eurasia.[97]

Extinction

[edit]

During theQuaternary extinction eventaround 12,700YBP, 90genera of mammals weighing over 44 kilograms (97 lb) became extinct.[54][68]The extinction of the large carnivores and scavengers is thought to have been caused by the extinction of the megaherbivore prey upon which they depended.[104][105][19][88]The cause of the extinction of the megafauna is debated[93]but has been attributed to the impact ofclimatic change,competitionwith other species includingoverexploitationby newly arrived human hunters, or a combination of both.[93][106]One study proposes that several extinction models should be investigated because so little is known about the biogeography of the dire wolf and its potential competitors and prey, nor how all these species interacted and responded to the environmental changes that occurred at the time of extinction.[19]

Ancient DNA and radiocarbon data indicate that local genetic populations were replaced by others within the same species or by others within the same genus.[107]Both the dire wolf and the Beringian wolf went extinct in North America, leaving only the less carnivorous and more gracile form of the wolf to thrive,[79]which may have outcompeted the dire wolf.[108]One study proposes an early origin of the dire wolf lineage in the Americas which led to its reproductive isolation, such that when coyotes, dholes, gray wolves, andXenocyonexpanded into North America from Eurasia in the Late Pleistocene there could be no admixture with the dire wolf. Gray wolves and coyotes may have survived due to their ability to hybridize with other canids – such as the domestic dog – to acquire traits that resist diseases brought by taxa arriving from Eurasia. Reproductive isolation may have prevented the dire wolf from acquiring these traits.[21]A 2023 study documented a high degree ofsubchondral defectsin joint surfaces of dire wolf andSmilodonspecimens from the La Brea Tar pits that resembledosteochondrosis dissecans.As modern dogs with this disease areinbred,the researchers suggested this would have been the case for the prehistoric species as well as they approached extinction, but cautioned that more research was needed to determine if this was also the case in specimens from other parts of the Americas.[109]

Dire wolf remains having the youngest geological ages are dated at 9,440YBP at Brynjulfson Cave,Boone County, Missouri,[31][108]9,860YBP at Rancho La Brea, California, and 10,690YBP atLa Mirada, California.[108]Dire wolf remains have been radiocarbon dated to 8,200YBP fromWhitewater DrawinArizona,[106][110]However, one author has stated that radiocarbon dating of bone carbonate is unreliable.[19]All of these dates areuncalibratedand the actual age of the remains is likely older. In South America, the most recent remains atTalara,Peru date to 9,030 ± 240 YBP (also uncalibrated), while the most recent remains of"C. nehringi"fromLuján,Argentina are older than the most recentstratigraphicalsection of the site, dated to 10–11,000 YBP.[111]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcdLeidy, J. (1858)."Notice of remains of extinct vertebrata, from the Valley of the Niobrara River, collected during the Exploring Expedition of 1857, in Nebraska, under the command of Lieut. G. K. Warren, U. S. Top. Eng., by Dr. F. V. Hayden, Geologist to the Expedition, Proceedings".Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.10:21.

- ^abMerriam, J.C. (1918)."Note on the systematic position of the wolves of the Canis dirus group".Bulletin of the Department of Geology of the University of California.10:533.

- ^abcdefghiKurtén, B. (1984). "Geographic differentiation in the Rancholabrean dire wolf (Canis dirusLeidy) in North America ". In Genoways, H. H.; Dawson, M. R. (eds.).Contributions in Quaternary Vertebrate Paleontology: A Volume in Memorial to John E. Guilday.Special Publication 8.Carnegie Museum of Natural History.pp.218–227.ISBN978-0-935868-07-4.

- ^abLeidy, J. (1854)."Notice of some fossil bones discovered by Mr. Francis A. Lincke, in the banks of the Ohio River, Indiana".Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.7(7): 200.

- ^abLeidy, J. (1869)."The extinct mammalian fauna of Dakota and Nebraska, including an account of some allied forms from other localities, together with a synopsis of the mammalian remains of North America".Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.7:368.

- ^abAllen, J. A. (1876)."Description of some remains of an extinct species of wolf and an extinct species of deer from the lead region of the upper Mississippi".American Journal of Science.s3-11 (61): 47–51.Bibcode:1876AmJS...11...47A.doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-11.61.47.hdl:2027/hvd.32044107326068.S2CID88320413.

- ^AMEGHINO, F. 1902. Notas sobre algunos mamíferos fósiles nuevos ó poco conocidos del valle de Tarija. Anales del Museo Nacional de Buenos Aires, 3º serie, 1:225–261

- ^Sellards, E.H. (1916)."Human remains and associated fossils from the Pleistocene of Florida".Annual Report of the Florida Geological Survey.8:152.

- ^Frick, C. (1930). "Alaska's frozen fauna".Natural History(30): 71–80.

- ^From Greekαἰνός(ainós) 'dreadful' +κύων(kúōn) 'dog' and Latindīrus'fearsome'

- ^Page Museum."View the collections at Rancho La Brea".The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Foundation.Archived fromthe originalon 25 January 2017.Retrieved19 December2016.

- ^ICZN (2017)."The Code online (refer Chapter 6, article 23.1)".International Code of Zoological Nomenclature online.International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-05-24.Retrieved2017-04-17.

- ^abcdefMerriam, J. C. (1912)."The fauna of Rancho La Brea, Part II. Canidae".Memoirs of the University of California.1:217–273.

- ^Troxell, E.L. (1915)."Vertebrate fossils of Rock Creek, Texas".American Journal of Science.189(234): 613–618.Bibcode:1915AmJS...39..613T.doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-39.234.613.

- ^Stevenson, Marc (1978)."9".In Hall, Roberta L.; Sharp, Henry S. (eds.).Wolf and Man: Evolution in Parallel.New York: Academic Press. p. 180.ISBN978-0-12-319250-9.Retrieved1 May2017.

- ^Lundelius, E. L. (1972). "Fossil vertebrates, late Pleistocene Ingleside Fauna, San Patricio County, Texas".Bureau of Economic Geology.Report of Investigations no.77: 1–74.

- ^abNowak 1979,pp. 106–108

- ^Wang, X. (1990). "Pleistocene dire wolf remains from the Kansas River with notes on dire wolves in Kansas".Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas.137:1–7.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoDundas, R.G. (1999)."Quaternary records of the dire wolf,Canis dirus,in North and South America "(PDF).Boreas.28(3): 375–385.Bibcode:1999Borea..28..375D.doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.1999.tb00227.x.S2CID129900134.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2020-09-27.Retrieved2015-08-28.

- ^abcdefghijkAnyonge, William; Roman, Chris (2006). "New body mass estimates forCanis dirus,the extinct Pleistocene dire wolf ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.26:209–212.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[209:NBMEFC]2.0.CO;2.S2CID83702167.

- ^abcdefghiPerri, Angela R.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Mouton, Alice; Álvarez-Carretero, Sandra; Hulme-Beaman, Ardern; Haile, James; Jamieson, Alexandra; Meachen, Julie; Lin, Audrey T.; Schubert, Blaine W.; Ameen, Carly; Antipina, Ekaterina E.; Bover, Pere; Brace, Selina; Carmagnini, Alberto; Carøe, Christian; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Chatters, James C.; Dobney, Keith; Dos Reis, Mario; Evin, Allowen; Gaubert, Philippe; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Gower, Graham; Heiniger, Holly; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Kapp, Josh; Kosintsev, Pavel A.; Linderholm, Anna; Ozga, Andrew T.; Presslee, Samantha; Salis, Alexander T.; Saremi, Nedda F.; Shew, Colin; Skerry, Katherine; Taranenko, Dmitry E.; Thompson, Mary; Sablin, Mikhail V.; Kuzmin, Yaroslav V.; Collins, Matthew J.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.;Gilbert, M. Thomas P.;Stone, Anne C.; Shapiro, Beth;Van Valkenburgh, Blaire;Wayne, Robert K.; Larson, Greger; Cooper, Alan; Frantz, Laurent A. F. (2021)."Dire wolves were the last of an ancient New World canid lineage".Nature.591(7848): 87–91.Bibcode:2021Natur.591...87P.doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03082-x.PMID33442059.S2CID231604957.

- ^Wang & Tedford 2008,pp. 20

- ^Wang, Xiaoming (2008)."How Dogs Came to Run the World".Natural History Magazine.Vol. July/August.Retrieved2014-05-24.

- ^Wang & Tedford 2008,pp. 49

- ^abTedford, Wang & Taylor 2009,pp. 4

- ^abcdefghiWang & Tedford 2008,pp. 148–150

- ^Wang & Tedford 2008,pp. 143–144

- ^abcdefTedford, Wang & Taylor 2009,pp. 181

- ^Martin, R. A.; Webb, S. D. (1974). "Late Pleistocene mammals from the Devil's Den fauna, Levy County". In Webb, S. D. (ed.).Pleistocene Mammals of Florida.Gainesville:University Press of Florida.pp.114–145.ISBN978-0-8130-0361-0.

- ^abBerta 1988,pp. 50

- ^abcdKurtén, B.; Anderson, E. (1980). "11-Carnavora".Pleistocene mammals of North America.Columbia University Press,New York. pp. 168–172.ISBN978-0-231-03733-4.

- ^Geist, Valerius (1998).Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behaviour, and Ecology(1 ed.). Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania:Stackpole Books.p. 10.ISBN978-0-8117-0496-0.Retrieved1 May2017.

- ^Geist, Valerius (1987). "On speciation in Ice Age mammals, with special reference to cervids and caprids".Canadian Journal of Zoology.65(5): 1067–1084.doi:10.1139/z87-171.

- ^abGoulet, G. D. (1993).Comparison of temporal and geographical skull variation among Nearctic, modern, Holocene, and late Pleistocene gray wolves (Canis lupus) and selectedCanis(Master's thesis). University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. pp. 1–116.

- ^abNowak 1979,pp. 102

- ^Nowak, Ronald M.; Federoff, Nicholas E. (Brusco) (2002). "The systematic status of the Italian wolfCanis lupus".Acta Theriologica.47(3): 333–338.doi:10.1007/BF03194151.S2CID366077.

- ^abR.M. Nowak (2003). "9-Wolf evolution and taxonomy". In Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi (eds.).Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation.University of Chicago Press.pp. 242–243.ISBN978-0-226-51696-7.

- ^Nowak 1979,pp. 84

- ^abcdeTedford, Wang & Taylor 2009,pp. 146–148

- ^abcPrevosti, Francisco J. (2010)."Phylogeny of the large extinct South American Canids (Mammalia, Carnivora, Canidae) using a" total evidence "approach".Cladistics.26(5): 456–481.doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00298.x.PMID34875763.S2CID86650539.Refer page 472

- ^Nowak 1979,pp. 93

- ^Lundelius, E.L.; Bell, C.J. (2004)."7 The Blancan, Irvingtonian, and Rancholabrean Mammal Ages"(PDF).In Michael O. Woodburne (ed.).Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America: Biostratigraphy and Geochronology.Columbia University Press. p. 285.ISBN978-0-231-13040-0.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 8 June 2017.Retrieved1 May2017.

- ^abMead, J. I.; Manganaro, C.; Repenning, C. A.; Agenbroad, L. D. (1996)."Early Rancholabrean mammals from Salamander Cave, Black Hills, South Dakota".In Stewart, K. M.; Seymour, K. L. (eds.).Palaeoecology and Palaeoenvironments of Late Cenozoic Mammals, Tributes to the Career of C. S. (Rufus) Churcher.University of Toronto Press,Toronto, Ontario, Canada. pp. 458–482.ISBN978-0-8020-0728-5.Archived fromthe originalon 2015-01-10.

- ^abcdefgMeachen, Julie A.; Brannick, Alexandria L.; Fry, Trent J. (2016)."Extinct Beringian wolf morphotype found in the continental U.S. has implications for wolf migration and evolution".Ecology and Evolution.6(10): 3430–8.Bibcode:2016EcoEv...6.3430M.doi:10.1002/ece3.2141.PMC4870223.PMID27252837.

- ^Berta 1988,pp. 113

- ^abNowak 1979,pp. 116–117

- ^abZrzavý, Jan; Duda, Pavel; Robovský, Jan; Okřinová, Isabela; Pavelková Řičánková, Věra (2018). "Phylogeny of the Caninae (Carnivora): Combining morphology, behaviour, genes and fossils".Zoologica Scripta.47(4): 373–389.doi:10.1111/zsc.12293.S2CID90592618.

- ^Lu, Dan; Yang, Yangheshan; Li, Qiang; Ni, Xijun (October 2020)."A late Pleistocene fossil from Northeastern China is the first record of the dire wolf (Carnivora: Canis dirus) in Eurasia".Quaternary International.591:87–92.Bibcode:2021QuInt.591...87L.doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.09.054.S2CID224877090– via ResearchGate.

- ^Koepfli, K.-P.; Pollinger, J.; Godinho, R.; Robinson, J.; Lea, A.; Hendricks, S.; Schweizer, R. M.; Thalmann, O.; Silva, P.; Fan, Z.; Yurchenko, A. A.; Dobrynin, P.; Makunin, A.; Cahill, J. A.; Shapiro, B.; Álvares, F.; Brito, J. C.; Geffen, E.; Leonard, J. A.; Helgen, K. M.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Wayne, R. K. (2015-08-17)."Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species".Current Biology.25(16): 2158–65.Bibcode:2015CBio...25.2158K.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060.PMID26234211.

- ^Alvares, Francisco; Bogdanowicz, Wieslaw; Campbell, Liz A.D.; Godinho, Rachel; Hatlauf, Jennifer; Jhala, Yadvendradev V.; Kitchener, Andrew C.; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Krofel, Miha; Moehlman, Patricia D.; Senn, Helen; Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; Viranta, Suvi; Werhahn, Geraldine (2019)."Old WorldCanisspp. with taxonomic ambiguity: Workshop conclusions and recommendations. CIBIO. Vairão, Portugal, 28th–30th May 2019 "(PDF).IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group.Retrieved6 March2020.

- ^Janczewski, D. N.; Yuhki, N.; Gilbert, D. A.; Jefferson, G. T.; O'Brien, S. J. (1992)."Molecular phylogenetic inference from saber-toothed cat fossils of Rancho La Brea".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.89(20): 9769–73.Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.9769J.doi:10.1073/pnas.89.20.9769.PMC50214.PMID1409696.

- ^Gold, David A.; Robinson, Jacqueline; Farrell, Aisling B.; Harris, John M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Jacobs, David K. (2014)."Attempted DNA extraction from a Rancho La Brea Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi): Prospects for ancient DNA from asphalt deposits ".Ecology and Evolution.4(4): 329–36.Bibcode:2014EcoEv...4..329G.doi:10.1002/ece3.928.PMC3936381.PMID24634719.

- ^abcdeStock, C. (1992).Rancho La Brea: A Record of Pleistocene Life in California.Science Series (7 ed.). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 1–113.ISBN978-0-938644-30-9.

- ^abcdO'Keefe, F.R.; Fet, E.V.; Harris, J.M. (2009)."Compilation, calibration, and synthesis of faunal and floral radiocarbon dates, Rancho La Brea, California"(PDF).Contributions in Science.518:1–16.doi:10.5962/p.226783.S2CID128107590.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2017-07-03.Retrieved2017-06-28.

- ^abTedford, Wang & Taylor 2009,pp. 325

- ^abcMech, L. David(1966).The Wolves of Isle Royale.Fauna Series 7. Fauna of the National Parks of the United States.ISBN978-1-4102-0249-9.Retrieved1 May2017.

- ^abcdHartstone-Rose, Adam; Dundas, Robert G.; Boyde, Bryttin; Long, Ryan C.; Farrell, Aisling B.; Shaw, Christopher A. (September 15, 2015). John M. Harris (ed.). "The Bacula of Rancho La Brea".Contributions in Science.Science Series 42 (A Special Volume Entitled la Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas in Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Excavations at Rancho la Brea). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County: 53–63.

- ^abcdStock, Chester; Lance, John F. (1948)."The Relative Lengths of Limb Elements inCanis dirus".Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences.47(3): 79–84.

- ^abSorkin, Boris (2008). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators".Lethaia.41(4): 333–347.Bibcode:2008Letha..41..333S.doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00091.x.

- ^"Gray wolf (in the Yukon)"(PDF).Environment Yukon.Government of Canada. 2017.Retrieved18 April2017.

- ^Rancho la Brea. Restoration by Chas. R. Knight. Mural for Amer. Museum Hall of Man. Coast Range in background, Old Baldy at left[1]

- ^Perri, Angela (2016). "A wolf in dog's clothing: Initial dog domestication and Pleistocene wolf variation".Journal of Archaeological Science.68:1–4.Bibcode:2016JArSc..68....1P.doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.003.

- ^Leonard, Jennifer (2014)."Ecology drives evolution in grey wolves"(PDF).Evolution Ecology Research.16:461–473.

- ^Flower, Lucy O.H.; Schreve, Danielle C. (2014). "An investigation of palaeodietary variability in European Pleistocene canids".Quaternary Science Reviews.96:188–203.Bibcode:2014QSRv...96..188F.doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.04.015.

- ^abcdefgHodnett, John-Paul; Mead Jim; Baez, A. (March 2009). "Dire Wolf,Canis dirus(Mammalia; Carnivora; Canidae), from the Late Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) of East-Central Sonora, Mexico ".The Southwestern Naturalist.54(1): 74–81.doi:10.1894/CLG-12.1.S2CID84760786.

- ^abcdefAnyonge, W.; Baker, A. (2006). "Craniofacial morphology and feeding behavior inCanis dirus,the extinct Pleistocene dire wolf ".Journal of Zoology.269(3): 309–316.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00043.x.

- ^abWroe, S.; McHenry, C.; Thomason, J. (2005)."Bite club: Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.272(1563): 619–25.doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2986.PMC1564077.PMID15817436.

- ^abcdefghijkO'Keefe, F.Robin; Binder, Wendy J.; Frost, Stephen R.; Sadlier, Rudyard W.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire (2014)."Cranial morphometrics of the dire wolf,Canis dirus,at Rancho La Brea: temporal variability and its links to nutrient stress and climate ".Palaeontologia Electronica.17(1): 1–24.

- ^abIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (UN) (2007)."IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007 – Palaeoclimatic Perspective".Nobel Foundation.Archived fromthe originalon 2015-10-30.Retrieved2016-12-11.

- ^abClark, P. U.; Dyke, A. S.; Shakun, J. D.; Carlson, A. E.; Clark, J.;Wohlfarth, B.;Mitrovica, J. X.; Hostetler, S. W.; McCabe, A. M. (2009). "The Last Glacial Maximum".Science.325(594 1): 710–4.Bibcode:2009Sci...325..710C.doi:10.1126/science.1172873.PMID19661421.S2CID1324559.

- ^Elias, S.A.; Schreve, D. (2016). "Late Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinctions".Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences(PDF).pp. 3202–3217.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10283-0.ISBN978-0-12-409548-9.S2CID130031864.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2016-12-20.

- ^abcdColtrain, Joan Brenner; Harris, John M.; Cerling, Thure E.; Ehleringer, James R.; Dearing, Maria-Denise; Ward, Joy; Allen, Julie (2004). "Rancho La Brea stable isotope biogeochemistry and its implications for the palaeoecology of late Pleistocene, coastal southern California".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.205(3–4): 199–219.Bibcode:2004PPP...205..199C.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2003.12.008.

- ^abcdFox-Dobbs, K.; Bump, J.K.; Peterson, R.O.; Fox, D.L.; Koch, P.L. (2007)."Carnivore-specific stable isotope variables and variation in the foraging ecology of modern and ancient wolf populations: Case studies from Isle Royale, Minnesota, and La Brea"(PDF).Canadian Journal of Zoology.85(4): 458–471.doi:10.1139/Z07-018.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 9 August 2017.Retrieved6 May2017.

- ^Moratto, Michael J. (1984).California Archaeology.Academic Press,Orlando, Florida. p. 89.ISBN978-0-12-506180-3.Retrieved1 May2017.

- ^Johnson, Donald Lee (1977). "The Late Quaternary Climate of Coastal California: Evidence for an Ice Age Refugium".Quaternary Research.8(2): 154–179.Bibcode:1977QuRes...8..154J.doi:10.1016/0033-5894(77)90043-6.S2CID129072450.

- ^College of Arts and Sciences (2016)."Rancho la Brea Tar Pool. Restoration by Bruce Horsfall for W.B. Scott".Case Western Reserve University.Retrieved24 December2016.

- ^Merriam, J.C. (1911).The fauna of Rancho La Brea.Vol. 1. University of California – Berkeley. pp.224–225.

- ^Valkenburgh, B. Van; Ruff, C. B. (1987). "Canine tooth strength and killing behaviour in large carnivores".Journal of Zoology.212(3): 379–397.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1987.tb02910.x.

- ^abcdLeonard, J. A.; Vilà, C; Fox-Dobbs, K; Koch, P. L.; Wayne, R. K.; Van Valkenburgh, B. (2007)."Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ectomorph"(PDF).Current Biology.17(13): 1146–50.Bibcode:2007CBio...17.1146L.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.072.hdl:10261/61282.PMID17583509.S2CID14039133.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 December 2016.Retrieved6 May2017.

- ^abMarcus, L. F.; Berger, R. (1984). "The significance of radiocarbon dates for Rancho La Brea". In Martin, P. S.; Klein, R. G. (eds.).Quaternary Extinctions.University of Arizona Press, Tucson. pp. 159–188.ISBN978-0-8165-0812-9.

- ^abMcHorse, Brianna K.; Orcutt, John D.; Davis, Edward B. (2012). "The carnivoran fauna of Rancho La Brea: Average or aberrant?".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.329–330: 118–123.Bibcode:2012PPP...329..118M.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.02.022.

- ^abcdVan Valkenburgh, Blaire; Sacco, Tyson (2002). "Sexual dimorphism, social behavior, and intrasexual competition in large Pleistocene carnivorans".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.22:164–169.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0164:SDSBAI]2.0.CO;2.S2CID86156959.

- ^abVan Valkenburgh, B.; Koepfli, K.-P. (1993). "Cranial and dental adaptations to predation in canids". In Dunston, N.; Gorman, J. L. (eds.).Mammals as Predators.Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 15–37.

- ^abVan Valkenburgh, B. (1998). "The decline of North American predators during the late Pleistocene". In Saunders, J. J.; Styles, B. W.; Baryshnikov, G. F. (eds.).Quaternary Paleozoology in the Northern Hemisphere.Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers, Springfield. pp. 357–374.ISBN978-0-89792-156-5.

- ^Carbone, C.; Maddox, T.; Funston, P. J.; Mills, M. G. L.; Grether, G. F.; Van Valkenburgh, B. (2009)."Parallels between playbacks and Pleistocene tar seeps suggest sociality in an extinct sabretooth cat,Smilodon".Biology Letters.5(1): 81–5.doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0526.PMC2657756.PMID18957359.

- ^Earle, M. (1987). "A flexible body mass in social carnivores".The American Naturalist.129(5): 755–760.doi:10.1086/284670.S2CID85236511.

- ^Fox-Dobbs, K.; Koch, P. L.; Clementz, M. T. (2003). "Lunchtime at La Brea: isotopic reconstruction ofSmilodon fatalisandCanis dirusdietary patterns through time ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.23(3, Supplement): 51A.doi:10.1080/02724634.2003.10010538.S2CID220410105.

- ^abcdefVan Valkenburgh, Blaire; Hertel, Fritz (1993)."Tough Times at La Brea: Tooth Breakage in Large Carnivores of the Late Pleistocene"(PDF).Science.New Series.261(5120): 456–459.Bibcode:1993Sci...261..456V.doi:10.1126/science.261.5120.456.PMID17770024.S2CID39657617.

- ^abVan Valkenburgh, B. (1988). "Incidence of tooth breakage among large predatory mammals".American Naturalist.131(2): 291–302.doi:10.1086/284790.S2CID222330098.

- ^abcdVan Valkenburgh, Blaire (2008)."Costs of carnivory: Tooth fracture in Pleistocene and Recent carnivorans".Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.96:68–81.doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01108.x.

- ^abBinder, Wendy J.; Thompson, Elicia N.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire (2002). "Temporal variation in tooth fracture among Rancho La Brea dire wolves".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.22(2): 423–428.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0423:TVITFA]2.0.CO;2.S2CID85799312.

- ^abTherrien, François (2005). "Mandibular force profiles of extant carnivorans and implications for the feeding behaviour of extinct predators".Journal of Zoology.267(3): 249–270.doi:10.1017/S0952836905007430.

- ^abcdeDeSantis, L.R.G.; Schubert, B.W.; Schmitt-Linville, E.; Ungar, P.; Donohue, S.; Haupt, R.J. (September 15, 2015). John M. Harris (ed.)."Dental microwear textures of carnivorans from the La Brea Tar Pits, California and potential extinction implications".Contributions in Science.Science Series 42 (A Special Volume Entitled la Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas in Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Excavations at Rancho la Brea). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County: 37–52.

- ^O'Keefe, F.R. (2008). "Population-level response of the dire wolf,Canis dirus,to climate change in the upper Pleistocene ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.28:122A.doi:10.1080/02724634.2008.10010459.S2CID220405736.

- ^Tseng, Zhijie Jack; Wang, Xiaoming (2010). "Cranial functional morphology of fossil dogs and adaptation for durophagy inBorophagusandEpicyon(Carnivora, Mammalia) ".Journal of Morphology.271(11): 1386–98.doi:10.1002/jmor.10881.PMID20799339.S2CID7150911.

- ^Wang & Tedford 2008,pp. 60

- ^abcDan, Lu; Yang, Yangheshan; Lia, Qiang; Nia, Xijun (1 October 2020). "A late Pleistocene fossil from Northeastern China is the first record of the dire wolf (Carnivora: Canis dirus) in Eurasia".Quaternary International.591:87–92.Bibcode:2021QuInt.591...87L.doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.09.054.S2CID224877090.

- ^Scott, Eric; Springer, Kathleen B. (2016)."First records ofCanis dirusandSmilodon fatalisfrom the late Pleistocene Tule Springs local fauna, upper Las Vegas Wash, Nevada ".PeerJ.4:e2151.doi:10.7717/peerj.2151.PMC4924133.PMID27366649.

- ^Tedford, Wang & Taylor 2009,p. 146.

- ^Caro, Francisco J.; Labarca, Rafael; Prevosti, Francisco J.; Villavicencio, Natalia; Jarpa, Gabriela M.; Herrera, Katherine A.; Correa-Lau, Jacqueline; Latorre, Claudio; Santoro, Calogero M. (2023). "First record of cf.Aenocyon dirus(Leidy, 1858) (Carnivora, Canidae), from the Upper Pleistocene of the Atacama Desert, northern Chile ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.42(4).doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2190785.S2CID258757704.

- ^Ruiz-Ramoni, Damián; Wang, Xiaoming; Rincón, Ascanio D. (2022)."Canids (Caninae) from the Past of Venezuela".Ameghiniana.59.doi:10.5710/AMGH.16.09.2021.3448.S2CID240576546.

- ^Berta 1988,pp. 119

- ^Webb, S.D. (1991). "Ecogeography and the great American interchange".Paleobiology.17(3): 266–280.Bibcode:1991Pbio...17..266W.doi:10.1017/S0094837300010605.S2CID88305955.

- ^Graham, R. W.; Mead, J. I. (1987). "Environmental fluctuations and evolution of mammalian faunas during the last deglaciation in North America". In Ruddiman, W. F.; Wright, H. E. (eds.).North America and Adjacent Oceans During the Last Deglaciation.Geological Society of America K–3, Boulder, Colorado. pp. 371–402.ISBN978-0-8137-5203-7.

- ^Barnosky, A. D. (1989). "The Late Pleistocene extinction event as a paradigm for widespread mammal extinction". In Donovan, Stephen K. (ed.).Mass Extinctions: Processes and Evidence.Columbia University Press,New York. pp. 235–255.ISBN978-0-231-07091-1.

- ^abBrannick, Alexandria L.; Meachen, Julie A.; O'Keefe, F. Robin (September 15, 2015). John M. Harris (ed.). "Microevolution of Jaw Shape in the Dire Wolf,Canis dirus,at Rancho La Brea ".Contributions in Science.Science Series 42 (A Special Volume Entitled la Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas in Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Excavations at Rancho la Brea). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County: 23–32.

- ^Cooper, A. (2015)."Abrupt warming events drove Late Pleistocene Holarctic megafaunal turnover".Science.349(6248): 602–6.Bibcode:2015Sci...349..602C.doi:10.1126/science.aac4315.PMID26250679.S2CID31686497.

- ^abcAnderson, Elaine (1984)."Chapter 2: Who's who in the Pleistocene".In Paul S. Martin; Richard G. Klein (eds.).Quaternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution.Tucson:University of Arizona Press.p. 55.ISBN978-0-8165-1100-6.

- ^Schmökel, Hugo; Farrell, Aisling; Balisi, Mairin F. (2023)."Subchondral defects resembling osteochondrosis dissecans in joint surfaces of the extinct saber-toothed catSmilodon fatalisand dire wolfAenocyon dirus".PLOS ONE.18(7): e0287656.Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1887656S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287656.PMC10337945.PMID37436967.

- ^Hester, Jim J. (1960). "Late Pleistocene Extinction and Radiocarbon Dating".American Antiquity.26(1): 58–77.doi:10.2307/277160.JSTOR277160.S2CID161116564.

- ^Prevosti, F. J., Tonni, E. P., & Bidegain, J. C. (2009). "Stratigraphic range of the large canids (Carnivora, Canidae) in South America, and its relevance to quaternary biostratigraphy".Quaternary International,210(1-2), 76-81.

Works cited

[edit]- Berta, A.(1988)."Quaternary evolution and biogeography of the large South American Canidae (Mammalia: Carnivora)".University of California Publications in Geological Sciences(132).ISBN978-0-520-09960-9.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (1979).North American Quaternary Canis.6. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas.doi:10.5962/bhl.title.4072.ISBN978-0-89338-007-6.Retrieved1 May2017.

- Tedford, Richard H.;Wang, Xiaoming;Taylor, Beryl E. (2009)."Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)"(PDF).Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.325:1–218.doi:10.1206/574.1.hdl:2246/5999.S2CID83594819.

- Wang, Xiaoming;Tedford, Richard H.(2008).Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History.Columbia University Press,New York. pp. 1–232.ISBN978-0-231-13529-0.

External links

[edit]- For younger readers –Dire Wolfby Marc Zabludoff, Marshall Cavendish, 2009

- The Evansville Dire Wolf

- Information on the dire wolf from the Illinois State Museum