Naïve realism

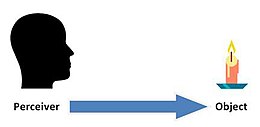

Inphilosophy of perceptionandepistemology,naïve realism(also known asdirect realismorperceptual realism) is the idea that thesensesprovide us with directawarenessofobjectsas they really are.[1]When referred to as direct realism, naïve realism is often contrasted withindirect realism.[2]

According to the naïve realist, the objects of perception are not representations of external objects, but are in fact those external objects themselves. The naïve realist is typically also ametaphysical realist,holding that these objects continue to obey the laws ofphysicsand retain all of their properties regardless of whether or not there is anyone to observe them.[3]They are composed ofmatter,occupyspace,and have properties, such as size, shape, texture, smell, taste and colour, that are usuallyperceivedcorrectly. The indirect realist, by contrast, holds that the objects of perception are simply representations of reality based on sensory inputs, and thus adheres to theprimary/secondary quality distinctionin ascribing properties to external objects.[1]

In addition to indirect realism, naïve realism can also be contrasted with some forms ofidealism,which claim that no world exists apart from mind-dependent ideas, and some forms ofphilosophical skepticism,which say that we cannot trust our senses or prove that we are notradically deceivedin our beliefs;[4]that our conscious experience is not of the real world but of an internal representation of the world.

Overview[edit]

The naïve realist is generally committed to the following views:[5]

- Metaphysical realism:There exists a world ofmaterialobjects, which exist independently of being perceived, and which have properties such as shape, size, color, mass, and so on independently of being perceived

- Empiricism:Some statements about these objects can be known to be true throughsensory experience

- Naïve realism: By means of our senses, we perceive the world directly, and pretty much as it is, meaning that our claims to haveknowledgeof it are justified

Amongcontemporaryanalytic philosopherswho defended direct realism one might refer to, for example,Hilary Putnam,[6]John McDowell,[7][8]Galen Strawson,[9]John R. Searle,[10]andJohn L. Pollock.[11]

Searle, for instance, disputes the popular assumption that "we can only directly perceive our own subjective experiences, but never objects and states of affairs in the world themselves".[12]According to Searle, it has influenced many thinkers to reject direct realism. But Searle contends that the rejection of direct realism is based on a bad argument: theargument from illusion,which in turn relies on vague assumptions on the nature or existence of "sense data".Various sense data theories were deconstructed in 1962 by the British philosopherJ. L. Austinin a book titledSense and Sensibilia.[13]

Talk of sense data has largely been replaced today by talk of representational perception in a broader sense, and scientific realists typically take perception to be representational and therefore assume that indirect realism is true. But the assumption is philosophical, and arguably little prevents scientific realists from assuming direct realism to be true. In a blog post on"Naive realism and color realism",Hilary Putnam sums up with the following words: "Being an apple is not a natural kind in physics, but it is in biology, recall. Being complex and of no interest to fundamental physics isn't a failure to be" real ". I think green is as real as applehood."[14]

The direct realist claims that the experience of a sunset, for instance, is the real sunset that we directly experience. The indirect realist claims that our relation to reality is indirect, so the experience of a sunset is a subjective representation of what really is radiation as described by physics. But the direct realist does not deny that the sunset is radiation; the experience has a hierarchical structure, and the radiation is part of what amounts to the direct experience.[12]

Simon Blackburnhas argued that whatever positions they may take in books, articles or lectures, naive realism is the view of "philosophers when they are off-duty."[15]

History[edit]

For a history of direct realist theories, seeDirect and indirect realism § History.

Scientific realism and naïve perceptual realism[edit]

Many philosophers claim that it is incompatible to accept naïve realism in thephilosophy of perceptionandscientific realismin thephilosophy of science.Scientific realism states that theuniversecontains just those properties that feature in ascientificdescription of it, which would mean thatsecondary qualitieslike color are not realper se,and that all that exists are certain wavelengths which are reflected by physical objects because of their microscopic surface texture.[16]

John Lockenotably held that the world only contains theprimary qualitiesthat feature in acorpuscularianscientific account of the world, and that secondary qualities are in some sensesubjectiveand depend for their existence upon the presence of some perceiver who can observe the objects.[3]

Influence in psychology[edit]

Naïve realism in philosophy has also inspired work onvisual perceptioninpsychology.The leading direct realist theorist in psychology wasJ. J. Gibson.Other psychologists were heavily influenced by this approach, including William Mace, Claire Michaels,[17]Edward S. Reed,[18]Robert Shaw, andMichael Turvey.More recently,Carol Fowlerhas promoted a direct realist approach tospeech perception.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^abThe Problem of Perception.Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2021.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^"The Contents of Perception".Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Retrieved12 July2020.

- ^abNaïve Realism,Theory of Knowledge.

- ^Lehar, Steve.RepresentationalismArchived2012-09-05 at theWayback Machine

- ^Naïve Realism,University of Reading.

- ^Putnam, Hilary. Sep. 1994. "The Dewey Lectures 1994: Sense, Nonsense, and the Senses: An Inquiry into the Powers of the Human Mind."The Journal of Philosophy91(9):445–518.

- ^John McDowell,Mind and World.Harvard University Press, 1994, p. 26.

- ^Roger F. Gibson, "McDowell's Direct Realism and Platonic Naturalism",Philosophical IssuesVol. 7,Perception(1996), pp. 275–281.

- ^Galen Strawson,"Real Direct Realism",a lecture recorded 2014 at Marc Sanders Foundation, Vimeo.

- ^John R. Searle,Seeing Things as They Are: A Theory of Perception,Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 15.

- ^John L. Pollock, Joseph CruzContemporary Theories of Knowledge,Rowman and Littlefield

- ^abJohn R. Searle, 'Seeing Things as They Are; A Theory of Perception', Oxford University Press. 2015. p.111-114

- ^Austin, J. L.Sense and Sensibilia,Oxford: Clarendon. 1962.

- ^"Sardonic comment".Putnamphil.blogspot.Retrieved9 April2019.

- ^Blackburn, Simon (2008). Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (Second edition, revised), Oxford University PressISBN9780199541430

- ^Michaels, Claire & Carello, Claudia. (1981).Direct PerceptionArchived2007-06-21 at theWayback Machine.Prentice-Hall.

- ^"Untitled Document".Archived fromthe originalon 2011-01-28.Retrieved2011-03-27.

- ^"Oxford University Press: Encountering the World: Edward S. Reed".Archived fromthe originalon 2011-05-25.Retrieved2011-03-27.

Sources and further reading[edit]

- Ahlstrom, Sydney E. "The Scottish Philosophy and American Theology,"Church History,Vol. 24, No. 3 (Sep., 1955), pp. 257–272in JSTOR

- Cuneo, Terence, and René van Woudenberg, eds.The Cambridge companion to Thomas Reid(2004)

- Gibson, J.J. (1972). A Theory of Direct Visual Perception. In J. Royce, W. Rozenboom (Eds.). The Psychology of Knowing. New York: Gordon & Breach.

- Graham, Gordon. "Scottish Philosophy in the 19th Century"Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(2009)online

- Marsden, George M.Fundamentalism and American Culture(2006)excerpt and text search

- S. A. Grave,"Common Sense", inThe Encyclopedia of Philosophy,ed.Paul Edwards(Collier Macmillan, 1967).

- Peter J. King,One Hundred Philosophers(2004: New York, Barron's Educational Books),ISBN0-7641-2791-8.

- Selections from the Scottish Philosophy of Common Sense,ed. by G.A. Johnston (1915)online,essays by Thomas Reid,Adam Ferguson,James Beattie, and Dugald Stewart

- David Edwards & Steven Wilcox (1982)."Some Gibsonian perspectives on the ways that psychologists use physics"(PDF).Acta Psychologica.52(1–2): 147–163.doi:10.1016/0001-6918(82)90032-4.

- Fowler, C. A. (1986)."An event approach to the study of speech perception from a direct-realist perspective".Journal of Phonetics.14:3–28.doi:10.1016/S0095-4470(19)30607-2.

- James J. Gibson.The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception.Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1987.ISBN0-89859-959-8

- Claire F. Michaels and Claudia Carello.Direct Perception.Prentice-Hall.ISBN978-0-13214-791-0.1981. Download this book athttps://web.archive.org/web/20070621155304/http://ione.psy.uconn.edu/~psy254/MC.pdf

- Edward S. Reed.Encountering the World.Oxford University Press, 2003.ISBN0-19-507301-0

- Sophia Rosenfeld.Common Sense: A Political History(Harvard University Press; 2011) 346 pages; traces the paradoxical history of common sense as a political ideal since 1688

- Shaw, R. E./Turvey, M. T./Mace, W. M. (1982): Ecological psychology. The consequence of a commitment to realism. In: W. Weimer & D. Palermo (Eds.), Cognition and the symbolic processes. Vol. 2, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp. 159–226.

- Turvey, M. T., & Carello, C. (1986). "The ecological approach to perceiving-acting a pictorial essay".Acta Psychologica.63(1–3): 133–155.doi:10.1016/0001-6918(86)90060-0.PMID3591430.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nicholas Wolterstorff.Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology.Cambridge University Press, 2006.ISBN0-521-53930-7

- Nelson, Quee. (2007).The Slightest PhilosophyDog's Ear Publishing.ISBN978-1-59858-378-6

- J L. Austin. (1962).Sense and Sensibilia.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0195003079

- John R., Searle. (2015).Seeing Things as They Are; A Theory of Perception.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-938515-7

External links[edit]

This article'suse ofexternal linksmay not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines.(April 2019) |

- James Feiser, "A Bibliography of Scottish Common Sense Philosophy"

- Naïve Realism and the Argument from Illusion

- Representationalism

- Naïve Realism in Contemporary Philosophy

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Epistemological Problems of Perception

- Physics and Commonsense: Reassessing the connection in the light of quantum theory

- Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods

- Nature Journal: Physicists bid farewell to reality?

- Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness

- Virtual Realism

- The reality of virtual reality

- IEEE Symposium on Research Frontiers in Virtual Reality: Understanding Synthetic Experience Must Begin with the Analysis of Ordinary Perceptual Experience

- Realism,article form theStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Sense Data,article from theStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Skepticism and the Veil of Perception,book defending direct realism.

- Pierre Le Morvan, "Arguments against direct realism and how to counter them",American Philosophical Quarterly41, no. 3 (2004): 221–234. (pdf)

- Steven Lehar, "Gestalt Isomorphism"(2003), paper criticizing direct realism.

- A Direct Realist Account of Perceptual Awareness,dissertation on direct realism.

- Epistemological debate on PSYCHE-D mailing list

- A Cartoon Epistemology