Dogme 95

| Years active | 1995–2005 |

|---|---|

| Location | International, started inDenmark |

| Major figures | Lars von Trier,Thomas Vinterberg,Kristian Levring,Søren Kragh-Jacobsen,Jean-Marc Barr,Harmony Korine |

| Influences | Realism,French New Wave |

| Influenced | Mumblecore,New Puritans,Remodernist,Philippine New Wave |

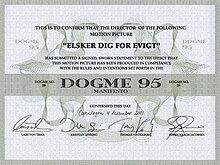

Dogme 95(Danish for "Dogma 95") is a 1995avant-gardefilmmaking movement founded by theDanishdirectorsLars von TrierandThomas Vinterberg,who created the "Dogme 95 Manifesto" and the "Vows of Chastity" (Danish:kyskhedsløfter). These were rules to create films based on the traditional values of story, acting, and theme, and excluding the use of elaborate special effects or technology. It was supposedly created as an attempt to "take back power for the directors as artists", as opposed to the studio.[1]They were later joined by fellow Danish directorsKristian LevringandSøren Kragh-Jacobsen,forming theDogme 95 Collectiveor theDogme Brethren.Dogme(pronounced[ˈtʌwmə]) is the Danish word fordogma.

The movement took Von Trier's first film underZentropa-productionBreaking the Wavesas the main inspiration by ethos although the film breaks many of the movement's "rules".[2]

History

[edit]Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg wrote and co-signed the manifesto and its companion "vows". Vinterberg said that they wrote the pieces in 45 minutes.[3]The manifesto initially mimics the wording ofFrançois Truffaut's 1954 essay "Une certaine tendance du cinéma français" inCahiers du cinéma.

They announced the Dogme movement on March 13, 1995, inParis,atLe cinéma vers son deuxième siècleconference. The cinema world had gathered to celebrate the first century of motion pictures and contemplate the uncertain future of commercial cinema. Called upon to speak about the future of film, Lars von Trier showered a bemused audience with red pamphlets announcing "Dogme 95".[citation needed]

In response to criticism, von Trier and Vinterberg have both stated that they just wanted to establish a new extreme: "In a business of extremely high budgets, we figured we should balance the dynamic as much as possible."[4]

In 1996, the movement tookBreaking the Wavesas the main inspiration by ethos, although the film breaks many of the movement's "rules", including built sets, post-dubbed music, violence, and computer graphics in the end of the film.[5][2]

Like theNo Wave Cinemacreative movement, Dogme 95 has been described as a defining period inlow budget filmproduction.[6][better source needed]

Since 2002 and the 31st film, Spanish director Juan Pinzás no longer needs to have his work verified by the original board to identify it as a Dogme 95 work after finishing up his own trilogy. The founding "brothers" have begun working on new experimental projects and have been skeptical about the later common interpretation of the Manifesto as a brand or a genre. The movement broke up in 2005.[7]

Since the late 2000s, the emergence of video technology in DSLR photography cameras, such as theCanon EOS 550D,has resulted in a tremendous surge of both feature and short films shot with most, if not all, of the rules pertaining to the Dogme 95 manifesto.[citation needed]However, because of advancements in technology and quality, the aesthetic of these productions typically appears drastically different from that of the Dogme films shot on Tape or DVD-R Camcorders. Largely erasing the primitive and problematic features of past technologies, newer technologies have helped Dogme 95 filmmakers achieve an aesthetic of higher resolution, as well as of lower contrast, film grain, and saturation.[citation needed]

Goals and rules

[edit]The goal of the Dogme collective is to "purify" filmmaking by refusing expensive and spectacular special effects, post-production modifications and other technicalgimmicks.The filmmakers concentrate on the story and the actors' performances. They claim this approach may better engage the audience, as they are not "alienated or distracted by overproduction". To this end, von Trier and Vinterberg produced ten rules to which any Dogme film must conform. These rules, referred to as the "Vow of Chastity", are as follows:[1]

- Shooting must be done on location.Propsand sets must not be brought in (if a particular prop is necessary for the story, a location must be chosen where this prop is to be found).

- The sound must never be produced apart from the images orvice versa.(Music must not be used unlessit occurs where the scene is being shot.)

- The camera must be hand-held. Any movement or immobility attainable in the hand is permitted.

- The film must be in colour. Special lighting is not acceptable. (If there is too little light for exposure the scene must be cut or a single lamp be attached to the camera.)

- Optical work and filters are forbidden.

- The film must not contain superficial action. (Murders, weapons, etc. must not occur.)

- Temporal and geographical alienation are forbidden. (That is to say that the film takes place here and now.)

- Genre moviesare not acceptable.

- The film format must beAcademy 35 mm.

- Thedirectormust not be credited.

″Furthermore I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste! I am no longer an artist. I swear to refrain from creating a “work”, as I regard the instant as more important than the whole. My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings. I swear to do so by all the means available and at the cost of any good taste and any aesthetic considerations. Thus I make my VOW OF CHASTITY.″[8]

Firsts

[edit]In total, thirty-five films made between 1998 and 2005 are considered to be part of the movement.

- The first of the Dogme films (Dogme #1) was Vinterberg's 1998 filmFesten(The Celebration), first produced in Denmark.

- Since the first four films from Denmark were released, other international directors have made films based onDogmeprinciples. French-American actor and directorJean-Marc Barr,von Trier's frequent collaborator, was the first non-Dane to direct a Dogme film:Lovers(1999) (Dogme #5).[citation needed]

- American directorHarmony Korine's filmJulien Donkey-Boy(Dogme #6) is also a first non-European and the first American film to be considered a Dogme.

- South Korean'sLa Femis-graduate and academicDaniel H. Byun,who directs his film debutInterview(Dogme #7), being the first and only Asian film ever made under the Dogme movement.

- Argentine filmmaker José Luis Marquès' mockumentary filmFuckland(Dogme #8), is the firstLatin Americanand the first Argentina film to follow the Dogme 95 movement minimalist guidelines.

- Trier attempted to make a Dogme trilogy, known as "Golden Heart"(consisting ofBreaking the Waves(1996),The Idiots(1998; Dogme #2), andDancer in the Dark(2000)), but onlyThe Idiotsis a certified Dogme 95 film whileBreaking the WavesandDancer in the Darkare sometimes associated or heavily laid out with the movement.[9]As a result, Pinzás was the only filmmaker to submit three films, making atrilogycalled "Gay Galician Dogma", which comprisesOnce Upon Another Time(2000; Dogme #22),Wedding Days(2002; Dogme #30), andThe Outcome(2005; Dogme #31)[10]

Attempts

[edit]WhileInterview(2000) does not explicitly mention that it is registered as Dogma #7, the number had originally referred to a scheduled German film titledBroken Cookies,directed by another one of von Trier's frequent collaborators,Udo Kier.The film was never produced, andInterviewwas registered instead.[11]

The end credits ofHet Zuiden(South) (2004), directed byMartin Koolhoven,included thanks to "Dogme 95". Koolhoven originally planned to shoot it as a Dogme film, and it was co-produced by von Trier'sZentropa.Finally, the director decided he did not want to be so severely constrained as by Dogme principles.[citation needed]

Uses and abuses

[edit]The above rules have been both circumvented and broken from numerous films submitted as a Dogme, particularly a director's credit and background music appearing inInterviewandFucklandas for examples. Some films include;

- For instance from the first Dogme film to be produced, Vinterberg "confessed" to having covered a window during the shooting of one scene inThe Celebration(Festen). With this, he both brought a prop onto the set and used "special lighting".

- Von Trier used background music (Le CygnebyCamille Saint-Saëns) in the filmThe Idiots(Idioterne).

- Korine'sJulien Donkey-Boyfeatures two scenes withnon-diegeticmusic, several shot with non-handheld, hidden cameras and a non-diegetic prop.

- Byun'sInterviewalso features that violated the rules including cramming in dolly shots, moody lighting, a director's credit, and Park's background music.[12]

- Márques'Fucklandbroke some of the Dogme 95 guidelines, including the use of non-diegetic music, digital video, and a directorial credit.

Concepts and influences

[edit]Breaking the Waves,von Trier's first film after founding the Dogme 95 movement, was heavily influenced by the Dogme 95 style and ethos, even though it breaks many of the "rules" (including a directorial credit, background sets, non-diegetic music, and use ofCGI).[5]

The 2001 experimental filmHotel,directed byMike Figgis,makes several mentions of the Dogme 95 style of filmmaking, and has been described as a "Dogme film-within-a-film".[13][14]

Keyboard player and music producerMoney Markused principles inspired by Dogme 95 to record hisMark's Keyboard Repairalbum.[15]

The Dogme 95 influenced Russian-born violinist Mikhail Gurewitsch to name his dogma chamber orchestra which he founded in 2004 in Germany.

Notable Dogme films

[edit]

A complete list of the 35 films is available from the Dogme95 web site.[16]Juan Pinzás (#22, #30, and #31) is the only filmmaker to have submitted more than once.

- Dogme #1:Festen

- Dogme #2:The Idiots

- Dogme #3:Mifune's Last Song

- Dogme #4:The King Is Alive

- Dogme #5:Lovers

- Dogme #6:Julien Donkey-Boy

- Dogme #7:Interview

- Dogme #8:Fuckland

- Dogme #12:Italian for Beginners

- Dogme #13:Amerikana

- Dogme #14:Joy Ride

- Dogme #28:Open Hearts

Reception

[edit]Most of the Dogme films received mixed or negative reviews, though some were critically acclaimed such as Vinterberg's filmFesten(The Celebration), Scherfig's filmItaliensk for begyndere(Italian for Beginners), and Bier's filmElsker dig for evigt(Open Hearts).[citation needed]Films such as Von Trier's filmIdioterne(The Idiots) and Jacobsen's filmMifunes sidste sang(Mifune's Last Song), also received lukewarm reviews.[citation needed]

Festenwon numerous awards including theJury Prizeat theCannes Film Festivaland won seven atRobert Awardsin 1998.[17]Italiensk for begynderealso won theSilver Bear Grand Jury Prizeat theBerlin Film Festivalin 2000.[citation needed]

In 2015, theMuseum of Arts and Designcelebrated the movement with the retrospectiveThe Director Must Not Be Credited: 20 Years of Dogme 95.The retrospective included work byLars von Trier,Thomas Vinterberg,Jean-Marc Barr,Susanne Bier,Daniel H. Byun,Harmony Korine,Kristian Levring,Annette K. Olesen,andLone Scherfig.[18][19]

Notable directors and actors/actresses appeared in films

[edit]- Miles Anderson

- Jean-Marc Barr[citation needed]

- Susanne Bier[citation needed]

- David Bradley

- Daniel H. Byun[citation needed]

- Søren Kragh-Jacobsen

- Lee Jung-jae

- Nicole Kidman

- Harmony Korine

- Jennifer Jason Leigh

- Kristian Levring[citation needed]

- Mads Mikkelsen

- Anthony Dod Mantle

- Richard Martini

- Lone Scherfig[citation needed]

- Chloë Sevigny

- Paprika Steen

- Thomas Vinterberg[citation needed]

- Lars von Trier

Legacy

[edit]Although the movement was dissolved in 2005, the filmmakers continued to develop independent and experimental films using or influenced the concept includingJan Dunn'sGypoandBrillante Mendoza's filmsSerbis,Tirador,andMa' Rosa.[20]

The use of 'Dogme 95' style filming is in a list of a hostage taker's demands in theBlack Mirrorepisode, "The National Anthem".[citation needed]

After the release of Byun's filmInterview(2000), some South Korean films who considered as an influence to Dogme 95 films, but rejected that serves as an actual Dogme; this includesThis Charming Girl(2004) byLee Yoon-Ki,Secret Sunshine(2007) byLee Chang-dong,andThe Housemaid(2010) byIm Sang-soo.[citation needed]

Much of Von Trier's works were influenced by the manifesto. His first film after founding the movement wasBreaking the Waves,which was heavily influenced by the movement's style and ethos, although the film broke many of the "rules" laid out by the movement's manifesto, including built sets, and usage of non-diegetic musics and computer graphics. Most of his films that followed these principles can be traced from the 1998 filmIdioterneuntilRiget: Exodus.[21][22]

Vinterberg's 2012 film,Jagten,was also influenced by the manifesto.[22]

Money Markhas stated that the albumMark's Keyboard Repairwas an "experimental concept based loosely on" the Dogme 95 idea.[23]

Academy Award-nomineeDaughter(2019) was inspired by its aesthetic.

See also

[edit]- Category:Dogme 95 films

- Minimalism

- Realism (arts)

- Pluginmanifesto

- New Puritans

- Stuckism

- New Sincerity

- Remodernism

- Remodernist film

- Post-postmodernism

Notes and references

[edit]- ^abUtterson, Andrew (2005).Technology and Culture, the Film Reader.Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-31985-0.

- ^abBodil Marie Stavning Thomsen (April 1, 2019)."Lars von Trier (b. 1956)".nordics.info.RetrievedAugust 17,2021.

- ^Krause, Stefanie (2007).The Implementing of the 'Vow of Chastity' in Jan Dunn's "Gypo".Verlag.ISBN978-3-638-76811-5.

- ^Sfectu, Nicolae (2014).The Art of Movies.

- ^abBreaking the WavesDVD liner notes. The Criterion Collection. 2014. Spine number 705. page 6.

- ^Coulter, Tomas (2004). "Low-budget movements that defined cinema" (Document). Tomas Coulter. p. 26.

- ^Kristian Levring interview(viaInternet Archive)

- ^"THE VOW OF CHASTITY | Dogme95.dk - A tribute to the official Dogme95".RetrievedNovember 16,2020.

- ^Unconventional TrilogiesArchived1 November 2014 at theWayback Machine,dated June 2013, at andsoitbeginsfilms

- ^Prout, Ryan."Speaking Up / Coming Out: Regions of Authenicity in Juan Pinzás's Gay Galician Dogma Trilogy"(PDF).Galicia.21(B).

- ^Schepelern, Peter (2005)."Films according to Dogma: Ground Rules, Obstacles, and Liberations".Wayne State University Press:99.ISBN0814332439.

- ^Kelly, Richard (December 10, 2000)."Film: So you really think you can do it Dogme style? Directors subscribing to the film-making manifesto need clear intentions to dodge stylistic traps, suggests Richard Kelly".The Independent:2.ProQuest311825376.

- ^Brook, Tom (April 6, 2002),"Figgis unlocks Hotel's secrets",BBC News,archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2014,retrievedFebruary 1,2014

- ^Ebert, Roger (September 26, 2003),Hotel,Roger Ebert,archivedfrom the original on February 20, 2014,retrievedFebruary 3,2014

- ^"Interview with Money Mark - Ableton".ableton.Archivedfrom the original on May 2, 2018.RetrievedMay 2,2018.

- ^"Dogme Films | Dogme95.dk - A tribute to the official Dogme95".dogme95.dk.Archivedfrom the original on December 31, 2017.RetrievedDecember 31,2017.

- ^"FESTEN".Festival de Cannes.RetrievedJuly 9,2024.

- ^"The Director Must Not Be Credited: 20 Years of Dogme 95".Museum of Arts and Design.Archivedfrom the original on July 26, 2015.RetrievedAugust 5,2015.

- ^Berman, Judy."What Dogme 95 did for women directors".The Dissolve.Pitchfork Media, Inc.Archivedfrom the original on July 26, 2015.RetrievedAugust 5,2015.

- ^Stevenson, Billy (January 26, 2019)."Mendoza: Ma'Rosa (2016)".cinematelevisionmusic.RetrievedSeptember 24,2022.

- ^Sondermann, Selina (September 5, 2022)."Venice Film Festival 2022: The Kingdom: Exodus (Riget: Exodus) | Review".The Upcoming.RetrievedOctober 2,2022.

- ^abLazic, Manuela (December 14, 2018)."The Hell That Lars von Trier Built".The Ringer.RetrievedSeptember 22,2022.

- ^"Interview with Money Mark | Ableton".ableton.RetrievedJanuary 17,2023.

External links

[edit]- "Interview: Mogens Rukov",Zakka

- "Lars From 1-10",10-minute film with reflections by von Trier on Dogme 95, The Perverts Guide

- Roberts, John (November–December 1999)."Dogme 95".New Left Review.I(238). New Left Review.

- Inside Cinema - Dogma 95