Donbas

Donbas

Донбас (Ukrainian) | |

|---|---|

Location of Donbas within Ukraine | |

| Country | Ukraine[note 1] |

| Largest city | Donetsk |

| Area | |

| • Total | 53,201 km2(20,541 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 6,651,378a |

| • Density | 125/km2(320/sq mi) |

| a. Before war | |

TheDonbas(UK:/dɒnˈbɑːs/,[2]US:/ˈdɒnbɑːs,dʌnˈbæs/;[3][4]Ukrainian:Донба́с[donˈbɑs];[5]) orDonbass(Russian:Донба́сс[dɐnˈbas][6]) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in easternUkraine.[7][8]Parts of the Donbasare occupiedbyRussiaas a result of theRusso-Ukrainian War.[9][10][11]

The wordDonbasis aportmanteauformed from "Donets Basin",an abbreviation of"Donets Coal Basin"(Ukrainian:Донецький вугільний басейн,romanized:Donetskyi vuhilnyi basein;Russian:Донецкий угольный бассейн,romanized:Donetskiy ugolnyy basseyn). The name of the coal basin is a reference to theDonets Ridge;the latter is associated with theDonetsriver.

There are numerous definitions of the region's extent.[12]TheEncyclopedia of History of Ukrainedefines the "small Donbas" as the northern part ofDonetskand the southern part ofLuhanskregions of Ukraine, and the attached part ofRostovregion of Russia.[13]The historicalcoal miningregion excluded parts of Donetsk and Luhanskoblasts,and included areas inDnipropetrovsk OblastandSouthern Russia.[8]AEuroregionof the same name is composed of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in Ukraine andRostov OblastinRussia.[14]

The Donbas formed the historical border between theZaporizhian Sichand theDon Cossack Host.It has been an important coal mining area since the late 19th century, when it became a heavily industrialised territory.[15]

In March 2014, following theEuromaidanprotest movement and the resultingRevolution of Dignity,large swaths of the Donbas became gripped bypro-Russian and anti-government unrest.This unrest later grew intoa warbetween Ukrainian government forces and pro-Russian separatists affiliated with the self-proclaimedDonetskandLuhansk"People's Republics", who were supported by Russia as part of the broaderRusso-Ukrainian War.The conflict split the Donbas into Ukrainian-held territory, constituting about two-thirds of the region, and separatist-held territory, constituting about one-third. The region remained this way for years until Russia launcheda full-scale invasion of Ukraine.On 30 September 2022, Russia unilaterally declared itsannexation of Donbas together with two other Ukrainian oblasts, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia.[16]

The city ofDonetsk(the fifth largest city in Ukraine) is considered the unofficialcapitalof the Donbas. Other large cities (over 100,000 inhabitants) includeLuhansk,Makiivka,Horlivka,Kramatorsk,Sloviansk,Mariupol,Alchevsk,Lysychansk,andSievierodonetsk.

History

Ancient, medieval and imperial Russian periods

TheKurgan hypothesisplaces thePontic steppesof Ukraine and southern Russia as thelinguistic homelandof theProto-Indo-Europeans.[18]TheYamnaya cultureis identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans.[19]

The region has been inhabited for centuries by various nomadic tribes, such asScythians,Alans,Huns,Bulgars,Pechenegs,Kipchaks,Turco-Mongols,TatarsandNogais.The region now known as the Donbas was largely unpopulated until the second half of the 17th century, whenDon Cossacksestablished the first permanent settlements in the region.[20]

The first town in the region was founded in 1676, called Solanoye (nowSoledar), which was built for the profitable business of exploiting newly discovered rock-salt reserves. Known for being aCossackland, the "Wild Fields"(Ukrainian:дике поле,dyke pole), the area that is now called the Donbas was largely under the control of the UkrainianCossack Hetmanateand the TurkicCrimean Khanateuntil the mid-late 18th century, when theRussian Empireconquered the Hetmanate and annexed the Khanate.[21][22]

In the second half of the 17th century, settlers and fugitives fromHetman's UkraineandMuscovysettled the lands north of theDonetsriver.[23]At the end of the 18th century, manyRussians,Ukrainians,SerbsandGreeksmigrated to lands along the southern course of the Donets river, into an area previously inhabited by nomadicNogais,who were nominally subject to the Crimean Khanate.[23][24]Tsarist Russia named the conquered territories "New Russia"(Russian:Новоро́ссия,Novorossiya). As theIndustrial Revolutiontook hold across Europe, the vastcoalresources of the region, discovered in 1721, began to be exploited in the mid-late 19th century.[25]

It was at this point that the nameDonbascame into use, derived from the term "Donets Coal Basin" (Ukrainian:Донецький вугільний басейн;Russian:Донецкий каменноугольный бассейн), referring to the area along theDonetsriver where most of the coal reserves were found. The rise of the coal industry led to a population boom in the region, largely driven by Russian settlers.[26]

Donetsk,the most important city in the region today, was founded in 1869 byWelshbusinessmanJohn Hugheson the site of the oldZaporozhian Cossacktown of Oleksandrivka. Hughes built a steel mill and established severalcollieriesin the region. The city was named after him as "Yuzovka" (Russian:Юзовка). With the development of Yuzovka and similar cities, large numbers of landless peasants from peripheralgovernorates of the Russian Empirecame looking for work.[27]

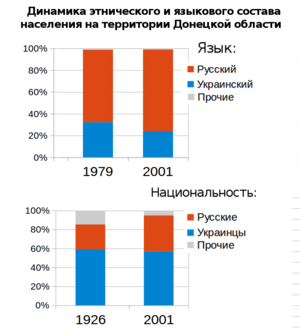

According to theRussian Imperial Censusof 1897, Ukrainians ( "Little Russians",in the official imperial language) accounted for 52.4% of the population of the region, whilst ethnic Russians constituted 28.7%.[28]Ethnic Greeks,Germans,JewsandTatarsalso had a significant presence in the Donbas, particularly in thedistrictofMariupol,where they constituted 36.7% of the population.[29]Despite this, Russians constituted the majority of the industrial workforce. Ukrainians dominated rural areas, but cities were often inhabited solely by Russians who had come seeking work in the region's heavy industries.[30]Those Ukrainians who did move to the cities for work were quickly assimilated into the Russian-speaking worker class.[31]

Russian Civil War and Soviet period (1918–1941)

In April 1918 troops loyal to theUkrainian People's Republictook control of large parts of the region.[32]For a while, its government bodies operated in the Donbas alongside theirRussian Provisional Governmentequivalents.[33]TheUkrainian State,the successor of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was able in May 1918 to bring the region under its control for a short time with the help of itsGermanandAustro-Hungarianallies.[33]

During the 1917–22Russian Civil War,Nestor Makhno,who commanded theRevolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine,was the most popular leader in the Donbas.[33]

Along with other territories inhabited by Ukrainians, the Donbas was incorporated into theUkrainian Soviet Socialist Republicin the aftermath of the Russian Civil War. Cossacks in the region were subjected todecossackisationduring 1919–1921.[34]Ukrainians in the Donbas were greatly affected by the 1932–33Holodomorfamine and theRussificationpolicy ofJoseph Stalin.As most ethnic Ukrainians were rural peasant farmers, they bore the brunt of the famine.[35][36]

Nazi occupation (1941–1943)

The Donbas was greatly affected by theSecond World War.In the lead-up to the war, the region was racked by poverty and food shortages. War preparations resulted in an extension of the working day for factory labourers, whilst those who deviated from the heightened standards were arrested.[37]Nazi Germany's leaderAdolf Hitlerviewed the resources of the Donbas as critical toOperation Barbarossa.As such, the Donbas suffered under Nazi occupation during 1941 and 1942.[38]

Thousands of industrial labourers were deported toNazi Germanyfor use in factories. In what was then called StalinoOblast,nowDonetsk Oblast,279,000 civilians were killed over the course of the occupation. In Voroshilovgrad Oblast, nowLuhansk Oblast,45,649 were killed.[39]

In 1943 theOperation Little SaturnandDonbas strategic offensiveby theRed Armyresulted in the return of Donbas to Soviet control. The war had taken its toll, leaving the region both destroyed and depopulated.

Soviet period (1943–1991)

During the reconstruction of the Donbas after the end of the Second World War, large numbers of Russian workers arrived to repopulate the region, further altering the population balance. In 1926, 639,000 ethnic Russians resided in the Donbas, and Ukrainians made up 60% of the population.[40]As a result of theRussificationpolicy, the Ukrainian population of the Donbass then declined drastically as ethnic Russians settled in the region in large numbers.[41]By 1959, the ethnic Russian population was 2.55 million. Russification was further advanced by the 1958–59 Soviet educational reforms, which led to the near elimination of all Ukrainian-language schooling in the Donbas.[42][43]By the time of theSoviet Census of 1989,45% of the population of the Donbas reported their ethnicity as Russian.[44]In 1990, theInterfront of the Donbasswas founded as a movement against Ukrainian independence.

In independent Ukraine (from 1991)

In the1991 referendumon Ukrainian independence, 83.9% of voters in Donetsk Oblast and 83.6% in Luhansk Oblast supported independence from theSoviet Union.Turnout was 76.7% in Donetsk Oblast and 80.7% in Luhansk Oblast.[45]In October 1991, a congress of South-Eastern deputies from all levels of government took place in Donetsk, where delegates demanded federalisation.[33]

The region's economy deteriorated severely in the ensuing years. By 1993, industrial production had collapsed, and average wages had fallen by 80% since 1990. The Donbas fell into crisis, with many accusing the new central government inKyivof mismanagement and neglect. Donbas coal miners went on strike in 1993, causing a conflict that was described by historian Lewis Siegelbaum as "a struggle between the Donbas region and the rest of the country". One strike leader said that Donbas people had voted for independence because they wanted "power to be given to the localities, enterprises, cities", not because they wanted heavily centralised power moved from "Moscow to Kyiv".[45]

This strike was followed by a 1994 consultative referendum on various constitutional questions in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, held concurrently with thefirst parliamentary electionsin independent Ukraine.[46]These questions included whether Russian should be declared an official language of Ukraine, whether Russian should be the language of administration in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, whether Ukraine should federalise, and whether Ukraine should have closer ties with theCommonwealth of Independent States.[47]

Close to 90% of voters voted in favour of these propositions.[48]None of them were adopted since the vote was nationwide. Ukraine remained aunitary state,Ukrainian was retained as the sole official language, and the Donbas gained no autonomy.[44]Nevertheless, the Donbas strikers gained many economic concessions from Kyiv, allowing for an alleviation of the economic crisis in the region.[45]

Small strikes continued throughout the 1990s, though demands for autonomy faded. Some subsidies to Donbas heavy industries were eliminated, and many mines were closed by the Ukrainian government because of liberalising reforms pushed for by theWorld Bank.[45]Leonid Kuchma,who had won the1994 presidential electionwith support from the Donbas and other areas in eastern Ukraine, was re-elected aspresident of Ukrainein1999.[45]President Kuchma gave economic aid to the Donbas, using development money to gain political support in the region.[45]

Power in the Donbas became concentrated in a regional political elite, known asoligarchs,during the early 2000s. Privatisation of state industries led to rampant corruption. Regional historian Hiroaki Kuromiya described this elite as the "Donbas clan", a group of people that controlled economic and political power in the region.[45]Prominent members of the "clan" includedViktor YanukovychandRinat Akhmetov.

A brief attempt at gaining autonomy by pro-Viktor Yanukovych politicians and officials was made in 2004 during theOrange Revolution.The so-calledSouth-East Ukrainian Autonomous Republicwas intended to consist out of nineSouth-Easternregions of Ukraine. The project was initiated on 26 November 2004 by the Luhansk Oblast Council, and was discontinued the next month by the Donetsk Oblast Council. On 28 November 2004, inSievierodonetsk,the so-calledFirst All-Ukraine Congress of People's Deputies And Local-Council's Deputies[uk]took place, organised by the supporters of Viktor Yanukovych.[49][50]

A total of 3,576 delegates from 16oblastsof Ukraine,CrimeaandSevastopoltook part in the congress, claiming to represent over 35 million citizens. Moscow MayorYurii Luzhkovand an advisor from the Russian Embassy were present in the presidium. There were calls for the appointment of Viktor Yanukovych as president of Ukraine orprime minister,for declaring of martial law in Ukraine, dissolution of theVerkhovna Rada,creation of self-defence forces, and for the creation of a federative South-Eastern state with its capital inKharkiv.[49][50]

Donetsk MayorOleksandr Lukyanchenko,however, stated that no one wanted autonomy, but rather sought to stop the Orange Revolution demonstrations going on at the time in Kyiv and negotiate a compromise. After the Orange Revolution's victory, some of the organisers of the congress were charged with "encroachment upon the territorial integrity and inviolability of Ukraine", but no convictions were made.[51][52]

In other parts of Ukraine during the 2000s, the Donbas was often perceived as having a "thug culture", as being a "Soviet cesspool", and as "backward". Writing in theNarodne slovonewspaper in 2005, commentator Viktor Tkachenko said that the Donbas was home to "fifth columns",and that speaking Ukrainian in the region was" not safe for one's health and life ".[53]It was also portrayed as being home to pro-Russian separatism. The Donbas is home to a significantly higher number of cities and villages that were named afterCommunistfigures compared to the rest of Ukraine.[54]Despite this portrayal, surveys taken across that decade and during the 1990s showed strong support for remaining within Ukraine and insignificant support for separatism.[55]

Russo-Ukrainian War (2014–present)

War in Donbas

From the beginning of March 2014, demonstrations bypro-Russianand anti-government groups took place in the Donbas, as part of the aftermath of theRevolution of Dignityand theEuromaidanmovement. These demonstrations, which followed theannexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation,and which were part of a wider group ofconcurrent pro-Russian protests across southern and eastern Ukraine,escalated in April 2014 intoa warbetween the Russian-backedseparatist forcesof the self-declaredDonetskandLuhanskPeople's Republics (DPR and LPR respectively), and theUkrainian government.[56][57]

Amid that conflict, the self-proclaimed republics heldreferendumson the status of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts on 11 May 2014. In the referendums, viewed as illegal by Ukraine and undemocratic by the international community, about 90% voted for the independence of the DPR and LPR.[58][note 2]

The initial protests in the Donbas were largely native expressions of discontent with the new Ukrainian government.[60]Russian involvement at this stage was limited to its voicing of support for the demonstrations. The emergence of the separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk began as a small fringe group of the protesters, independent of Russian control.[60][61]This unrest, however, only evolved into an armed conflict because of Russian military backing for what had been a marginal group as part of theRusso-Ukrainian War.The conflict was thus, in the words of historian Hiroaki Kuromiya, "secretly engineered and cleverly camouflaged by outsiders".[62]

There was limited support for separatism in the Donbas before the outbreak of the war, and little evidence of support for an armed uprising.[63]Russian claims that Russian speakers in the Donbas were being persecuted or even subjected to "genocide"by the Ukrainian government, forcing its hand to intervene, were deemed false.[62][64]

Fighting continued through the summer of 2014, and by August 2014, the Ukrainian "Anti-Terrorist Operation" was able to vastly shrink the territory under the control of the pro-Russian forces, and came close to regaining control of the Russo-Ukrainian border.[65]In response to the deteriorating situation in the Donbas, Russia abandoned what has been called its "hybrid war"approach, and begana conventional invasionof the region.[65][66]As a result of the Russian invasion, DPR and LPR insurgents regained much of the territory they had lost during the Ukrainian government's preceding military offensive.[67]

Only this Russian intervention prevented an immediate Ukrainian resolution to the conflict.[68][69][70]This forced the Ukrainian side to seek the signing of a ceasefire agreement.[71]Called theMinsk Protocol,this was signed on 5 September 2014.[72]As this failed to stop the fighting, another agreement, calledMinsk IIwas signed on 12 February 2015.[73]This agreement called for the eventual reintegration of the Donbas republics into Ukraine, with a level of autonomy.[73]The aim of the Russian intervention in the Donbas was to establish pro-Russian governments that, upon reincorporation into Ukraine, would facilitate Russian interference in Ukrainian politics.[74]The Minsk agreements were thus highly favourable to the Russian side, as their implementation would accomplish these goals.[75]

The conflict led to a vast exodus from the Donbas: half the region's population were forced to flee their homes.[76]AUN OHCHRreport released on 3 March 2016 stated that, since the conflict broke out in 2014, the Ukrainian government registered 1.6 million internally displaced people who had fled the Donbas to other parts of Ukraine.[77]Over 1 million were said to have fled elsewhere, mostly to Russia. At the time of the report, 2.7 million people were said to continue to live in areas under DPR and LPR control,[77]comprising about one-third of the Donbas.[78]

Despite the Minsk agreements, low-intensity fighting along the line of contact between Ukrainian government and Russian-controlled areas continued until 2022. Since the start of the conflict there have been 29 ceasefires, each intended to remain in force indefinitely, but none of them stopped the violence.[79][80][81]This led the war to be referred to as a "frozen conflict".[82] On 11 January 2017, the Ukrainian government approved a plan to reintegrate the occupied part of the Donbas and its population into Ukraine.[83]The plan would give Russian-backed political entities partial control of the electorate and has been described byZerkalo Nedelias "implanting a cancerous cell into Ukraine's body."[84]This was never implemented, and was subject to public protest.

A 2018 survey bySociological Group "Rating"of residents of the Ukrainian-controlled parts of the Donbas found that 82% of respondents believed there was no discrimination against Russian-speaking people in Ukraine.[85]Only 11% saw some evidence of discrimination.[85]The same survey also found that 71% of respondents did not support Russia's military intervention to "protect" the Russian-speaking population, with only 9% offering support for that action.[85]Another survey by Rating, conducted in 2019, found that only 23% of those Ukrainians polled supported granting the Donbas autonomous status,[86]whilst 34% supported a ceasefire and "freezing" the conflict, 23% supported military action to recover the occupied Donbas territories, and 6% supported separating these territories from Ukraine.[86]

Full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 21 February 2022, Russia officially recognised theindependence of the Donetsk and Luhanskrepublics,[87][88]effectively killing theMinsk agreements.[89]Russia subsequently launched a new,full-scale invasion of Ukraineon 24 February 2022, which Russian presidentVladimir Putinsaid was intended to "protect" the people of the Donbas from the "abuse" and "genocide" of the Ukrainian government.[90][91]However, Putin's claims have been refuted.[92][93]The DPR and LPR joined Russia's operation; the separatists stated that an operation to capture the entirety of Donetsk Oblast and Luhansk Oblast had begun.[94]

On 18 April 2022, thebattle of Donbasbegan, a Russian offensive in mid-2022 within the largereastern Ukraine campaign.[95][96]

Demographics and politics

According to the 2001 census, ethnic Ukrainians form 58% of the population of Luhansk Oblast and 56.9% of Donetsk Oblast.Ethnic Russiansform the largest minority, accounting for 39% and 38.2% of the two oblasts respectively.[97]In the present day, the Donbas is a predominatelyRussophone region.According to the 2001 census, Russian is the main language of 74.9% of residents in Donetsk Oblast and 68.8% in Luhansk Oblast.[98]

Residents of Russian origin are mainly concentrated in the larger urban centers. Russian became the main language andlingua francain the course of industrialization, boosted by the immigration of many Russians, particularly fromKursk Oblast,to newly founded cities in the Donbas. A subject of continuing research controversies, and often denied in these two oblasts, is the extent of forced emigration and deaths during the Soviet period, which particularly affected rural Ukrainians during the Holodomor which resulted as a consequence of early Soviet industrialization policies combined with two years of drought throughout southern Ukraine and the Volga region.[99][100]

Nearly all Ukrainian Jews either fled or were murdered inthe Holocaust in Ukraineduring theGerman occupation in World War II.The Donbas is about 6%Muslimaccording to the official censuses of1926and2001.

Prior to the Revolution of Dignity, the politics of the region were dominated by the pro-RussianParty of Regions,which gained about 50% of Donbas votes in the2008 Ukrainian parliamentary election.Prominent members of that party, such as former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, were from the Donbas.

According to linguistGeorge Shevelov,in the early 1920s the proportion ofsecondary schoolsteaching in the Ukrainian language was lower than the proportion of ethnic Ukrainians in the Donbas[101]– even though the Soviet Union had ordered[when?]that all schools in theUkrainian SSRshould be Ukrainian-speaking (as part of itsUkrainizationpolicy).[102]

Surveys of regional identities in Ukraine have shown that around 40% of Donbas residents claim to have a "Soviet identity".[103]Roman HorbykofSödertörn Universitywrote that in the 20th century, "[a]s peasants from all surrounding regions were flooding its then busy mines and plants on the border of ethnically Ukrainian and Russian territories", "incomplete and archaic institutions" prevented Donbas residents from "acquiring a notably strong modern urban – and also national – new identity".[101]

Religion

Religion in Donbas (2016)[104]

According to a 2016 survey ofreligion in Ukraineheld by theRazumkov Center,65.0% of the population in the Donbas believe inChristianity(including 50.6% Orthodox, 11.9% who declared themselves to be "simply Christians", and 2.5% who belonged toProtestantchurches).Islamis the religion of 6% of the population of the Donbas andHinduismof the 0.6%, both the religions with a share of the population that is higher compared to other regions of Ukraine. People who declared to be not believers or believers in some other religions, not identifying in one of those listed, were 28.3% of the population.[104]

Economy

TheGross regional productof Donbas was ₴335 billion (€10 billion) in 2021.[105]

In 2013 (before war) GDP of Donbas was ₴220 billion (€20 billion).[106]

The Donbas economy is dominated byheavy industry,such ascoal miningandmetallurgy.The region takes its name from an abbreviation of the term "Donets Coal Basin" (Ukrainian:Донецький вугільний басейн,Russian:Донецкий угольный бассейн), and while annual extraction of coal has decreased since the 1970s, the Donbas remains a significant producer. The Donbas represents one of the largest coal reserves in Ukraine, with estimated reserves of 60 billion tonnes of coal.[107]

Coal mining in the Donbas is conducted at very deep depths. Lignite mining takes place at around 600 metres (2,000 ft) below the surface, whilst mining for the more valuableanthraciteandbituminous coaltakes place at depths of around 1,800 metres (5,900 ft).[25]Prior to the start of the region's war in April 2014, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts together produced about 30 percent of Ukraine's exports.[108]

Other industries in the Donetsk region include blast-furnace and steel-making equipment, railway freight-cars, metal-cutting machine-tools, tunneling machines, agricultural harvesters and ploughing systems, railway tracks, mining cars, electric locomotives, military vehicles, tractors and excavators. The region also produces consumer goods like household washing-machines, refrigerators, freezers, TV sets, leather footwear, and toilet soap. Over half its production is exported,[when?]and about 22% is exported to Russia.[109]

In mid-March 2017, Ukrainian presidentPetro Poroshenkosigned a decree on a temporary ban on the movement of goods to and from territory controlled by the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic, so since then Ukraine does not buy coal from the Donets Coal Basin.[110]

Shale gasreserves, part of the largerDnieper–Donets basin,[111]are present in the Donbas, most notably theYuzivska gas field.[112]In an effort to reduce Ukrainian dependence on Russian gas imports, the Ukrainian government reached an agreement withRoyal Dutch Shellin 2012 to develop the Yuzivska field.[112]Shell was forced to freeze operations after the outbreak of war in the region in 2014, and officially withdrew from the project in June 2015.[113]

Occupational safety in the coal industry

The coal mines of the Donbas are some of the mosthazardousin the world because of the deep depths of mines, as well as frequentmethane explosions,coal-dust explosions,rock burstdangers, and outdated infrastructure.[114]Even more hazardous illegal coal mines became very common across the region in the late 2000s.[15][115]

Environmental problems

Intensive coal-mining andsmeltingin the Donbas have led to severe damage to the local environment. The most common problems throughout the region include:

- water-supply disruption and flooding due to themine water

- visible air pollution aroundcokeandsteel mills

- air/water contamination andmudslidethreat fromspoil tips

Additionally, severalchemical waste-disposal sites in the Donbas have not been maintained, and pose a constant threat to the environment. One unusual threat is the result of the Soviet-era1979 project[uk]to test experimentalnuclear mininginYenakiieve.For example, on 16 September 1979, at the Yunkom Mine, known today as the Young Communard mine in Yenakiyeve, a 300kt nuclear test explosion was conducted at 900m to free methane gas or to degasified coal seams into a sandstone oval dome known as theKlivazh[Rift] Site so that methane would not pose a hazard or threat to life.[116]BeforeGlasnost,no miners were informed of the presence of radioactivity at the mine, however.[116]

Culture and religion

Sviatohirsk(Holy Mountain City) is the main religious sanctuary of the region. Near the city is located theSviatohirsk Lavra.The monastery was restored following thedissolution of the Soviet Unionand theindependence of Ukraine.In 2004 the monastery was granted the status oflavra.In 1997 area around the monastery was turned into theHoly Mountains National Nature Park.

See also

- Donbass Arena

- HC Donbass,an ice hockey team based inDonetskbearing the name of the region

- Russians in Ukraine

- Kryvbas

Notes

References

- ^"Ukraine Census, population as of 1st August 2012".State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Archived fromthe originalon 12 March 2010.Retrieved20 June2009.

- ^"Donbas".LexicoUK English Dictionary.Oxford University Press.Archived fromthe originalon 1 March 2021.

- ^"Donbas".The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language(5th ed.). HarperCollins.Retrieved6 September2019.

- ^"Donbas".Merriam-Webster Dictionary.Retrieved26 December2021.

- ^"Donets Basin – region, Europe".Encyclopaedia Britannica.4 June 2023.

- ^Как далеко зайдет Москва на Донбассе. Срочное обращение Байдена. Первые санкции | ВЕЧЕР | 22.2.22.VoA(in Russian).Voice of America.22 February 2022.Retrieved22 February2022.

- ^"Donets Basin".LexicoUK English Dictionary UK English Dictionary.Oxford University Press.Archived fromthe originalon 22 April 2021.

- ^abHiroaki Kuromiya (2003).Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s.Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–13.ISBN0521526086.

- ^Kitsoft."Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine – Temporary Occupation of Territories in Donetsk and Luhansk Regions".mfa.gov.ua.Retrieved26 January2022.

- ^Kitsoft."Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine – 10 facts you should know about the Russian military aggression against Ukraine".mfa.gov.ua.Retrieved26 January2022.

- ^"A Russian court document mentioned Russian troops" stationed "in eastern Ukraine. Moscow insists there are none".CBS News. 17 December 2021.Retrieved26 January2022.

- ^Тимошенко, Денис (23 June 2018).Донбасс – единственная часть Украины, возникшая из промышленного региона[Donbass is the only part of Ukraine that emerged from an industrial region].Radio Liberty(in Russian).Retrieved7 December2023.

- ^"ДОНБАС, РЕГІОН В УКРАЇНІ ТА РОСІЇ".resource.history.org.ua.Retrieved20 June2024.

- ^"Euroregion Donbass".Association of European Border Regions. Archived fromthe originalon 16 March 2018.Retrieved12 March2015.

- ^ab"The coal-mining racket threatening Ukraine's economy".BBC News.23 April 2013.Retrieved18 September2013.

- ^Dickson, Janice (30 September 2022)."Putin signs documents to illegally annex four Ukrainian regions, in drastic escalation of Russia's war".The Globe and Mail.Retrieved5 March2023.

- ^Gibbons, Ann (21 February 2017)."Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population".Science.

- ^Balter, Michael (13 February 2015)."Mysterious Indo-European homeland may have been in the steppes of Ukraine and Russia".Science.

- ^Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (11 June 2015)."Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe".Nature.522(7555): 207–211.arXiv:1502.02783.Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H.doi:10.1038/nature14317.ISSN0028-0836.PMC5048219.PMID25731166.

- ^Katchanovski, Ivan; Kohut, Zenon E.; Nebesio, Bohdan Y.; Yurkevich, Myroslav (11 July 2013).Historical Dictionary of Ukraine.Lanham:Scarecrow Press. pp. 135–136.ISBN978-0-8108-7847-1.

- ^Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003).Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s.Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–13.ISBN0521526086.

- ^Hauter, Jakob (2023).Russia's Overlooked Invasion: The Causes of the 2014 Outbreak of War in Ukraine's Donbas.Ibidem Verlag. p. 14.ISBN978-3-8382-1803-8.

- ^abAllen, W. E. D. (2014).The Ukraine.Cambridge University Press. p. 362.ISBN978-1107641860.

- ^Yekelchyk, Serhy (2015).The Conflict in Ukraine: What Everyone Needs to Know.Oxford University Press. p. 113.ISBN978-0190237301.

- ^ab"Donets Basin".Encyclopædia Britannica.2014.

- ^Andrew Wilson (April 1995). "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes".Journal of Contemporary History.30(2): 274.JSTOR261051.

- ^Klinova, Olha (11 December 2014).Як формувалась регіональна ідентичність Донбасу[How the Donbas identity was formed].Istorychna Pravda.Retrieved7 December2023.

- ^Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003).Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s.Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–42.ISBN0521526086.

- ^"The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 − Breakdown of population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia".Institute of Demography at the National Research University 'Higher School of Economics'.Archived fromthe originalon 6 October 2014.Retrieved22 September2014.

- ^Lewis H. Siegelbaum; Daniel J. Walkowitz (1995).Workers of the Donbass Speak: Survival and Identity in the New Ukraine, 1982–1992.Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 162.ISBN0-7914-2485-5.

- ^Stephen Rapawy (1997).Ethnic Reidentification in Ukraine(PDF).Washington, D.C.: United States Census Bureau. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 19 October 2012.Retrieved7 March2015.

- ^"100 років тому визволили Бахмут і решту Донбасу"[100 years ago Bakhmut and the rest of Donbas liberated].Istorychna Pravda(in Ukrainian). 18 April 2018.Retrieved7 December2023.

- ^abcdLessons for the Donbas from two wars,The Ukrainian Week(16 January 2019)

- ^"Soviet order to exterminate Cossacks is unearthed".University of York.19 November 2010.Retrieved11 September2014.

'Ten thousand Cossacks were slaughtered systematically in a few weeks in January 1919 [...] 'And while that wasn't a huge number in terms of what happened throughout the Russia, it was one of the main factors which led to the disappearance of the Cossacks as a nation. [...]'

- ^Potocki, Robert (2003).Polityka państwa polskiego wobec zagadnienia ukraińskiego w latach 1930–1939(in Polish and English). Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej.ISBN978-8-391-76154-0.

- ^Piotr Eberhardt (2003).Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe.Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. pp. 208–209.ISBN0-7656-0665-8.

- ^Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003).Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s.Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–255.ISBN0521526086.

- ^Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003).Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s.Cambridge University Press. p. 251.ISBN0521526086.

- ^Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003).Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s.Cambridge University Press. p. 273.ISBN0521526086.

- ^Andrew Wilson (April 1995). "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes".Journal of Contemporary History.30(2): 275.JSTOR261051.

By 1924 there were 158 Ukrainian schools in the Donbas; by 1930 44 per cent of the 'industrial apparat' was Ukrainian-speaking; while the percentage of the working class who considered themselves Ukrainian supposedly rose from 40.6 per cent in 1926 to 70 per cent in 1929 (the overall population of the Donbas was 60 per cent Ukrainian in 1926).

- ^Andrew Wilson (April 1995). "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes".Journal of Contemporary History.30(2): 275.JSTOR261051.

Russification was achieved first and foremost through the physical inflow of huge numbers of Russians in the years after 1945. Their numbers grew from 0.77 million in 1926 to 2.55 million in 1959 and 3.6 million in 1989. In percentage terms the number of Russians grew from 31.4 per cent in 1926 to 44 per cent in 1989.

- ^L.A. Grenoble (2003).Language Policy in the Soviet Union.Springer Science & Business Media.ISBN1402012985.

- ^Bohdan Krawchenko (1985).Social change and national consciousness in twentieth-century Ukraine.Macmillan.ISBN0333361997.

- ^abDon Harrison Doyle, ed. (2010).Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements.University of Georgia Press. pp. 286–287.ISBN978-0820330082.

- ^abcdefgOliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008).Europe's Last Frontier?.New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 103–105.ISBN978-0-230-60372-1.

- ^Kataryna Wolczuk (2001).The Moulding of Ukraine.Central European University Press. pp. 129–188.ISBN9789639241251.

- ^Hryhorii Nemyria (1999).Regional Identity and Interests: The Case of East Ukraine.Studies in Contemporary History and Security Policy.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^Bohdan Lupiy."Ukraine And European Security – International Mechanisms As Non-Military Options For National Security of Ukraine".Individual Democratic Institutions Research Fellowships 1994–1996.NATO.Retrieved21 September2014.

- ^abThe Congress of the Victors ( "Съезд победителей" ),Zerkalo Nedeli[in Russian],zn.ua

- ^ab"The Congress of Regions" took place in Sievierodonetsk[in Ukrainian],bbc

- ^Head of the Luhansk Oblast Council was charged with separatism[in Ukrainian],ua.korrespondent.net

- ^Ukrainian Governors are accused of separatism[in Russian],rbc.ru

- ^Oliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008).Europe's Last Frontier?.New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 102–103.ISBN978-0-230-60372-1.

- ^"В Україні перейменують 22 міста і 44 селища"[In Ukraine rename 22 cities and 44 villages].Ukrainska Pravda(in Ukrainian). 4 June 2015.Retrieved7 December2023.

- ^Oliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008).Europe's Last Frontier?.New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 108–111.ISBN978-0-230-60372-1.

- ^Grytsenko, Oksana (12 April 2014)."Armed pro-Russian insurgents in Luhansk say they are ready for police raid".Kyiv Post.

- ^Leonard, Peter (14 April 2014)."Ukraine to deploy troops to quash pro-Russian insurgency in the east".Yahoo News Canada.Associated Press. Archived fromthe originalon 14 April 2014.Retrieved26 October2014.

- ^abWiener-Bronner, Daniel (11 May 2014)."Referendum on Self-Rule in Ukraine 'Passes' with Over 90% of the Vote".The Wire.Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved12 May2014.

"Ukraine denounces pro-Russian referendums".The Globe and Mail.11 May 2014.Retrieved12 May2014. - ^East Ukraine goes to the polls for independence referendum | The Observer.The Guardian.10 May 2014.

- ^abKofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017).Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine(PDF)(Report). Santa Monica: Rand Corporation. pp. 33–34.

- ^Wilson, Andrew (20 April 2016). "The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but not Civil War".Europe-Asia Studies.68(4): 631–652.doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1176994.ISSN0966-8136.S2CID148334453.

- ^abKuromiya, Hiroaki."The Enigma of the Donbas: How to Understand Its Past and Future".historians.in.ua.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^Wilson, Andrew (20 April 2016). "The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but not Civil War".Europe-Asia Studies.68(4): 641.doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1176994.ISSN0966-8136.S2CID148334453.

- ^"Defending Ukraine Threat, Putin Regurgitates Misleading 'Genocide' Claim".Polygraph.info.18 February 2022.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^abKofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017).Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine(PDF)(Report). Santa Monica: Rand Corporation. p. 44.

- ^Snyder, Timothy (3 April 2018).The road to unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America(First ed.). New York. p. 191.ISBN978-0-525-57446-0.OCLC1029484935.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Ivan Katchanovski(1 October 2016)."The Separatist War in Donbas: A Violent Break-up of Ukraine?".European Politics and Society.17(4): 473–489.doi:10.1080/23745118.2016.1154131.ISSN2374-5118.S2CID155890093.

- ^Freedman, Lawrence (2 November 2014)."Ukraine and the Art of Limited War".Survival.56(6): 13.doi:10.1080/00396338.2014.985432.ISSN0039-6338.S2CID154981360.

- ^Wilson, Andrew (20 April 2016). "The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but not Civil War".Europe-Asia Studies.68(4): 634, 649.doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1176994.ISSN0966-8136.S2CID148334453.

- ^Mykhnenko, Vlad (15 March 2020)."Causes and Consequences of the War in Eastern Ukraine: An Economic Geography Perspective".Europe-Asia Studies.72(3): 528–560.doi:10.1080/09668136.2019.1684447.ISSN0966-8136.

- ^"The background to the Minsk agreements".Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^"The Minsk-1 agreement".Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^ab"The Minsk-2 agreement".Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^"Conclusions".Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^Kofman, Michael; Migacheva, Katya; Nichiporuk, Brian; Radin, Andrew; Tkacheva, Olesya; Oberholtzer, Jenny (2017).Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine(PDF)(Report). Santa Monica: Rand Corporation. pp. 45–46.

- ^Kuznetsova, Irina (15 March 2020)."To Help 'Brotherly People'? Russian Policy Towards Ukrainian Refugees"(PDF).Europe-Asia Studies.72(3): 505–527.doi:10.1080/09668136.2020.1719044.ISSN0966-8136.S2CID216252795.

- ^abReport on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 November 2015 to 15 February 2016(PDF).Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 3 March 2016.Retrieved3 March2016.

- ^Seddon, Max; Chazan, Guy; Foy, Henry (22 February 2022)."Putin backs separatist claims to whole Donbas region of Ukraine".Financial Times.Retrieved4 March2022.

- ^"Найдовше перемир'я на Донбасі. Чи воно існує насправді"[The longest truce in Donbas. Does it really exist].Ukrainska Pravda(in Ukrainian). 7 September 2020.Retrieved7 December2023.

- ^New Year ceasefire enters into force in Donbass,TASS(29 December 2018)

- ^"Four DPR servicemen killed in shellings by Ukrainian troops in past week".Information Telegraph Agency of Russia.23 October 2018.Retrieved28 October2018.

- ^"Ukraine accuses separatists of abusing Minsk deal with land grab".Reuters.21 January 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 21 March 2017.Retrieved22 January2015.

- ^"Government's plan for the reintegration of Donbas: the pros, cons and alternatives | UACRISIS.ORG".[:en]Ukraine crisis media center [:ua]Український кризовий медіа-центр.24 January 2017.Retrieved19 February2017.

- ^"Ukraine's leaders may be giving up on reuniting the country".The Economist.11 February 2017.Retrieved19 February2017.

- ^abcСоціологія: ідеї руського миру в неокупованому Донбасі скоріше маргінальні(Report) (in Ukrainian). Sociological Group "Rating". 13 January 2016.

- ^ab"ATTITUDES OF UKRAINIANS TOWARDS THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ISSUE SOLUTION".Sociological Group "Rating".2 October 2019.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^"Russia recognises Ukraine separatist regions as independent states".BBC News. 21 February 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2022.Retrieved21 February2022.

- ^"Locals in Ukraine breakaway regions recount short-lived joy, hope".Al Jazeera. 1 March 2022.

- ^Rathke, Jeff (27 February 2022)."Putin Accidentally Started a Revolution in Germany".Foreign Policy.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^"Russia launches" full-scale invasion "of Ukraine, sparks international outcry".Kyodo News.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^"Ukraine-Russia crisis: Ukraine: Russia has launched 'full-scale invasion'".BBC News.Retrieved24 February2022.

- ^"Putin's claims that Ukraine is committing genocide are baseless, but not unprecedented".The Conversation.25 February 2022.

- ^"PolitiFact – Vladimir Putin repeats false claim of genocide in Ukraine".Washington, DC.Retrieved3 March2022.

- ^Troianovski, Anton; MacFarquhar, Neil (23 February 2022)."Ukraine Live Updates: Russia Begins Invasion From Land and Sea".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved24 February2022.

- ^"Battle of Donbas begins: Why Russia has turned its attention to east of Ukraine".Firstpost.20 April 2022.

- ^"Ukraine says 'Battle of Donbas' has begun, Russia pushing in east".Reuters.18 April 2022.

- ^"About number and composition population of UKRAINE by data All-Ukrainian population census 2001 data".State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 17 December 2011.

- ^"Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 – English version – Results – General results of the census –& Linguistic composition of the population".2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua.

- ^"Ukrainian 'Holodomor' (man-made famine) Facts and History".holodomorct.org.Archived fromthe originalon 24 April 2013.Retrieved17 October2016.

- ^"The Cause and the Consequences of Famines in Soviet Ukraine".faminegenocide.Archived fromthe originalon 15 March 2016.Retrieved19 March2018.

- ^abGames from the Past: The continuity and change of the identity dynamic in Donbas from a historical perspective,Södertörn University(19 May 2014)

- ^Language Policy in the Soviet UnionbyLenore Grenoble,Springer Science+Business Media,2003,ISBN978-1-4020-1298-3(page 84)

- ^Soviet conspiracy theories and political culture in Ukraine:Understanding Viktor Yanukovych and the Party of RegionArchived16 May 2014 at theWayback MachinebyTaras Kuzio(23 August 2011)

- ^abРЕЛІГІЯ, ЦЕРКВА, СУСПІЛЬСТВО І ДЕРЖАВА: ДВА РОКИ ПІСЛЯ МАЙДАНУ (Religion, Church, Society and State: Two Years after Maidan)Archived22 April 2017 at theWayback Machine,2016 report byRazumkov Centerin collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches. pp. 27–29.

- ^""Валовии регіональнии продукт"".ukrstat.gov.ua(in Ukrainian).Retrieved25 September2023.

- ^Gross regional product in 2004-2019,archived fromthe originalon 23 May 2021

- ^"Coal in Ukraine"(PDF).edu.ua. 2012. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 15 December 2017.Retrieved23 July2013.

- ^Oliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008).Europe's Last Frontier?.New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 97.ISBN978-0-230-60372-1.

- ^"Donets'k Region – Regions of Ukraine – MFA of Ukraine".mfa.gov.ua.

- ^Ukrainian energy industry: thorny road of reform,Ukrainian Independent Information Agency(10 January 2018)

- ^"Assessment of Undiscovered Continuous Oil and Gas Resources in the Dnieper-Donets Basin and North Carpathian Basin Provinces, Ukraine, Romania, Moldova, and Poland, 2015"(PDF).U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^abGent, Stephen E. (2021).Market power politics: war, institutions, and strategic delays in world politics.New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 159.ISBN978-0-19-752984-3.OCLC1196822660.

- ^Olearchyk, Roman (11 June 2015)."Shell to withdraw from shale gas exploration in eastern Ukraine".Financial Times.Retrieved8 March2022.

- ^Grumau, S. (2002). Coal mining in Ukraine. Economic Review. 44.

- ^Panova, Kateryna (8 July 2011)."Illegal mines profitable, but at massive cost to nation".Kyiv Post.Retrieved18 September2013.

- ^abKazanskyi, Denys (16 April 2018),"Disaster in the making: The" DPR government "has announced its intention to flood the closed Young Communard mine in Yenakiyeve. 40 years ago, nuclear tests were carried out in it, and nobody knows today what the consequences would be if groundwater erodes the radioactive rock",The Ukrainian Week,retrieved5 October2018

External links

- "Deconstructing the Donbass", overview of the 2014–2015 conflict,Archived19 October 2017 at theWayback Machinemidwestdiplomacy

- "The coal-mining racket threatening Ukraine's economy"byBBC News

- Bulletin board "Объявления Донбасса",Archived7 April 2022 at theWayback Machinedonbass.men