Douglas DC-3

| DC-3 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A DC-3 operated in periodScandinavian Airlinescolours byFlygande Veteranerflying overLidingö,Sweden, in 1989 | |

| Role | Airlinerand transport aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| First flight | December 17, 1935 |

| Introduction | 1936, withAmerican Airlines |

| Status | In service |

| Produced | 1936–1942, 1950 |

| Number built | 607[1] |

| Developed from | Douglas DC-2 |

| Variants | Douglas C-47 Skytrain Douglas R4D-8/C-117D Lisunov Li-2 Showa/Nakajima L2D Basler BT-67 Conroy Turbo-Three Conroy Tri-Turbo-Three |

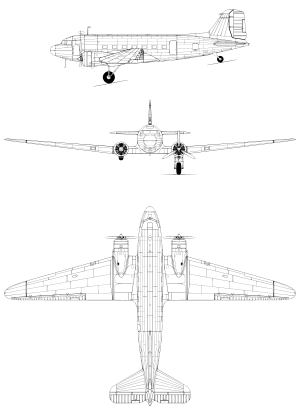

TheDouglas DC-3is apropeller-drivenairliner manufactured byDouglas Aircraft Company,which had a lasting effect on theairlineindustry in the 1930s to 1940s andWorld War II. It was developed as a larger, improved 14-bed sleeper version of theDouglas DC-2. It is alow-wingmetal monoplane withconventional landing gear,powered by two radial piston engines of 1,000–1,200 hp (750–890 kW). Although the DC-3s originally built for civil service had theWright R-1820 Cyclone,later civilian DC-3s used thePratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Waspengine.[2] The DC-3 has a cruising speed of 207 mph (333 km/h), a capacity of 21 to 32 passengers or 6,000 lbs (2,700 kg) of cargo, and a range of 1,500 mi (2,400 km), and can operate from short runways.

The DC-3 had many exceptional qualities compared to previous aircraft. It was fast, had a good range, was more reliable, and carried passengers in greater comfort. Before the war, it pioneered many air travel routes. It was able to cross thecontinental United Statesfrom New York to Los Angeles in 18 hours, with only three stops. It is one of the first airliners that could profitably carry only passengers without relying on mail subsidies.[3][4]In 1939, at the peak of its dominance in the airliner market, around ninety percent of airline flights on the planet were by a DC-3 or some variant.[5]

Following the war, the airliner market was flooded with surplus transport aircraft, and the DC-3 was no longer competitive because it was smaller and slower than aircraft built during the war. It was made obsolete on main routes by more advanced types such as theDouglas DC-4andConvair 240,but the design proved adaptable and was still useful on less commercially demanding routes.

Civilian DC-3 production ended in 1943 at 607 aircraft. Military versions, including theC-47 Skytrain(the Dakota in BritishRAFservice), and Soviet- and Japanese-built versions, brought total production to over 16,000. Many continued to be used in a variety of niche roles; 2,000 DC-3s and military derivatives were estimated to be still flying in 2013;[6]by 2017 more than 300 were still flying.[7]As of 2023 it is estimated about 150 are still flying.[8]

Design and development[edit]

"DC" stands for "Douglas Commercial". The DC-3 was the culmination of a development effort that began after an inquiry fromTranscontinental and Western Airlines(TWA) toDonald Douglas.TWA's rival in transcontinental air service,United Airlines,was starting service with theBoeing 247,and Boeing refused to sell any 247s to other airlines until United's order for 60 aircraft had been filled.[9]TWA asked Douglas to design and build an aircraft that would allow TWA to compete with United. Douglas' design, the 1933DC-1,was promising, and led to theDC-2in 1934. The DC-2 was a success, but with room for improvement.

The DC-3 resulted from a marathon telephone call fromAmerican AirlinesCEOC. R. Smithto Donald Douglas, when Smith persuaded a reluctant Douglas to design a sleeper aircraft based on the DC-2 to replace American'sCurtiss Condor IIbiplanes. The DC-2's cabin was 66 inches (1.7 m) wide, too narrow for side-by-side berths. Douglas agreed to go ahead with development only after Smith informed him of American's intention to purchase 20 aircraft. The new aircraft was engineered by a team led by chief engineerArthur E. Raymondover the next two years, and the prototype DST (Douglas Sleeper Transport) first flew on December 17, 1935 (the 32nd anniversary of theWright Brothers' flight at Kitty Hawk) with Douglas chief test pilotCarl Coverat the controls. Its cabin was 92 in (2,300 mm) wide, and a version with 21 seats instead of the 14–16 sleeping berths[11]of the DST was given the designationDC-3.No prototype was built, and the first DC-3 built followed seven DSTs off the production line for delivery to American Airlines.[12]

The DC-3 and DST popularized air travel in the United States. Eastbound transcontinental flights could cross the U.S. in about 15 hours with three refueling stops, while westbound trips against the wind took17+1⁄2hours. A few years earlier, such a trip entailed short hops in slower and shorter-range aircraft during the day,coupled with train travel overnight.[13]

Severalradial engineswere offered for the DC-3. Early-production civilian aircraft used either the 9-cylinderWright R-1820 Cyclone 9or the 14-cylinderPratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp,but the Twin Wasp was chosen for most military versions and was also used by most DC-3s converted from military service. Five DC-3SSuper DC-3swithPratt & Whitney R-2000 Twin Waspswere built in the late 1940s, three of which entered airline service.

Production[edit]

Total production including all military variants was 16,079.[14]More than 400 remained in commercial service in 1998. Production was:

- 607 civilian variants

- 10,048 military C-47 and C-53 derivatives built atSanta Monica, California,Long Beach, California,andOklahoma City

- 4,937 built under license in the Soviet Union (1939–1950) as theLisunov Li-2(NATO reporting name:Cab)

- 487Mitsubishi Kinsei-engined aircraft built by Showa and Nakajima in Japan (1939–1945), as theL2D Type 0 transport(Allied codenameTabby)

Production of DSTs ended in mid-1941 and civilian DC-3 production ended in early 1943, although dozens of the DSTs and DC-3s ordered by airlines that were produced between 1941 and 1943 were pressed into the US military service while still on the production line.[15][16]Military versions were produced until the end of the war in 1945. A larger, more powerful Super DC-3 was launched in 1949 to positive reviews. The civilian market was flooded with second-hand C-47s, many of which were converted to passenger and cargo versions. Only five Super DC-3s were built, and three of them were delivered for commercial use. The prototype Super DC-3 served the US Navy with the designation YC-129 alongside 100 R4Ds that had been upgraded to the Super DC-3 specifications.

Turboprop conversions[edit]

From the early 1950s, some DC-3s were modified to useRolls-Royce Dartengines, as in theConroy Turbo Three.Other conversions featuredArmstrong Siddeley MambaorPratt & Whitney PT6Aturbines.

The Greenwich Aircraft Corp DC-3-TP is a conversion with an extended fuselage and withPratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-65AR or PT6A-67Rengines fitted.[17][18][19]

TheBasler BT-67is a conversion of the DC-3/C-47. Basler refurbishes C-47s and DC-3s atOshkosh,Wisconsin,fitting them with Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-67R turboprop engines, lengthening the fuselage by 40 in (1,000 mm) with a fuselage plug ahead of the wing, and some local strengthening of the airframe.[20]

South Africa-based Braddick Specialised Air Services International (commonly referred to as BSAS International) has also performed Pratt & Whitney PT6 turboprop conversions, having performed modifications on over 50 DC-3/C-47s / 65ARTP / 67RTP / 67FTPs.[21]

Operational history[edit]

American Airlines inaugurated passenger service on June 26, 1936, with simultaneous flights fromNewark, New JerseyandChicago,Illinois.[22]Early U.S. airlines likeAmerican,United,TWA,Eastern,andDeltaordered over 400 DC-3s. These fleets paved the way for the modern American air travel industry, which eventually replacedtrainsas the favored means of long-distance travel across the United States. A nonprofit group, Flagship Detroit Foundation, continues to operate the only original American Airlines Flagship DC-3 with air show and airport visits throughout the U.S.[23]

In 1936,KLMRoyal Dutch Airlines received its first DC-3, which replaced the DC-2 in service fromAmsterdamvia Batavia (nowJakarta) toSydney,by far the world's longest scheduled route at the time. In total, KLM bought 23 DC-3s before the war broke out in Europe.[citation needed]In 1941, aChina National Aviation Corporation(CNAC) DC-3 pressed into wartime transportation service was bombed on the ground at Suifu Airfield in China, destroying the outer right wing. The only spare available was that of a smaller Douglas DC-2 in CNAC's workshops. The DC-2's right wing was removed, flown to Suifu under the belly of another CNAC DC-3, and bolted up to the damaged aircraft. After a single test flight, in which it was discovered that it pulled to the right due to the difference in wing sizes, the so-called DC-2½ was flown to safety.[24]

During World War II, many civilian DC-3s were drafted for the war effort and more than 10,000 U.S. military versions of the DC-3 were built, under the designationsC-47, C-53, R4D, and Dakota.Peak production was reached in 1944, with 4,853 being delivered.[25]The armed forces of many countries used the DC-3 and its military variants for the transport of troops, cargo, and wounded. Licensed copies of the DC-3 were built in Japan as the Showa L2D (487 aircraft); and in the Soviet Union as theLisunov Li-2(4,937 aircraft).[14]

After the war, thousands of cheap ex-military DC-3s became available for civilian use.[26]Cubana de Aviaciónbecame the first Latin American airline to offer a scheduled service toMiamiwhen it started its first scheduled international service fromHavanain 1945 with a DC-3. Cubana used DC-3s on some domestic routes well into the 1960s.[27][28]

Douglas developed an improved version, the Super DC-3, with more power, greater cargo capacity, and an improved wing, but with surplus aircraft available for cheap, they failed to sell well in the civilian aviation market.[29]Only five were delivered, three of them toCapital Airlines.The U.S. Navy had 100 of its early R4Ds converted to Super DC-3 standard during the early 1950s as theDouglas R4D-8/C-117D.The last U.S. Navy C-117 was retired July 12, 1976.[30]The last U.S. Marine Corps C-117, serial 50835, was retired from active service during June 1982. Several remained in service with small airlines in North and South America in 2006.[31]

TheUnited States Forest Serviceused the DC-3 forsmoke jumpingand general transportation until the last example was retired in December 2015.[32]

A number of aircraft companies attempted to design a "DC-3 replacement" over the next three decades (including the very successfulFokker F27 Friendship), but no single type could match the versatility, rugged reliability, and economy of the DC-3. While newer airliners soon replaced it on longer high-capacity routes, it remained a significant part of air transport systems well into the 1970s as a regional airliner before being replaced by earlyregional jets.

DC-3 in the 21st century[edit]

Perhaps unique among prewar aircraft, the DC-3 continues to fly in active commercial and military service as of 2021, eighty-six years after the type's first flight in 1935, although the number is dwindling due to expensive maintenance and a lack of spare parts.[citation needed]There are small operators with DC-3s in revenue service and ascargo aircraft.Applications of the DC-3 have included passenger service, aerial spraying, freight transport, military transport, missionary flying,skydivershuttling and sightseeing. There have been a very large number of civil and military operators of the DC-3/C-47 and related types, which would have made it impracticable to provide a comprehensive listing of all operators.

A common saying among aviation enthusiasts and pilots is "the only replacement for a DC-3 is another DC-3".[33][34] Its ability to use grass or dirt runways makes it popular in developing countries or remote areas, where runways may be unpaved.[35][36]

The oldest surviving DST is N133D, the sixth Douglas Sleeper Transport built, manufactured in 1936. This aircraft was delivered toAmerican Airlineson 12 July 1936 as NC16005. In 2011 it was at Shell Creek Airport,Punta Gorda, Florida.[37]It has been repaired and has been flying again, with a recent flight on 25 April 2021.[38][39]The oldest DC-3 still flying is the original American AirlinesFlagship Detroit(c/n 1920, the 43rd aircraft off the Santa Monica production line, delivered on 2 March 1937),[40]which appears at airshows around the United States and is owned and operated by the Flagship Detroit Foundation.[23]

The base price of a new DC-3 in 1936 was around $60,000–$80,000, and by 1960 used aircraft were available for $75,000.[41]In 2023, flying DC-3s can be bought from $400,000-$700,000.

As of 2024, the Basler BT-67 with additions to handle cold weather and snow runways are used in Antarctica including regularly landing at the South Pole during the austral summer.

Original operators[edit]

Variants[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(December 2017) |

Civil[edit]

- DST

- Douglas Sleeper Transport; the initial variant with two 1,000–1,200-horsepower (750–890 kW)Wright R-1820 Cycloneengines and standard sleeper accommodation for up to 16 with small upper windows, convertible to carry up to 24 day passengers.[42]

- DST-A

- DST with 1,000–1,200 hp (750–890 kW)Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Waspengines

- DC-3

- Initial non-sleeper variant; with 21 day-passenger seats, 1,000–1,200 hp (750–890 kW) Wright R-1820 Cyclone engines, no upper windows.

- DC-3A

- DC-3 with 1,000–1,200 hp (750–890 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines.

- DC-3B

- Version of DC-3 for TWA, with two 1,100–1,200 hp (820–890 kW) Wright R-1820 Cyclone engines and smaller convertible sleeper cabin forward with fewer upper windows than DST.

- DC-3C

- Designation for ex-military C-47, C-53, and R4D aircraft rebuilt by Douglas Aircraft in 1946, given new manufacturer numbers, and sold on the civil market; Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engines.[43]

- DC-3D

- Designation for 28 new aircraft completed by Douglas in 1946 with unused components from the cancelled USAAF C-117 production line; Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engines.[44]

- DC-3S

- Also known as Super DC-3, substantially redesigned DC-3 with fuselage lengthened by 39 inches (1.0 m); outer wings of a different shape with squared-off wingtips and shorter span; distinctive taller rectangular tail; and fitted with more powerfulPratt & Whitney R-2000or 1,475 hp (1,100 kW) Wright R-1820 Cyclone engines. Five completed by Douglas for civil use using existing surplus secondhand airframes.[45]Three Super DC-3s were operated by Capital Airlines 1950–1952.[46]Designation also used for examples of the 100 R4Ds that had been converted by Douglas to this standard for the U.S. Navy as R4D-8s (later designated C-117Ds), all fitted with more powerful Wright R-1820 Cyclone engines, some of which entered civil use after retirement from military service.[47]

Military[edit]

- C-41, C-41A

- The C-41 was the first DC-3 to be ordered by the USAAC and was powered by two 1,200 hp (890 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1830-21 engines. It was delivered in October 1938 for use byUnited States Army Air Corps(USAAC) chief GeneralHenry H. Arnoldwith the passenger cabin fitted out in a 14-seat VIP configuration.[48]The C-41A was a single VIP DC-3A supplied to the USAAC in September 1939, also powered by R-1830-21 engines; and used by theSecretary of War.The forward cabin converted to sleeper configuration with upper windows similar to the DC-3B.[49][50]

- C-48

- Various DC-3A and DST models; 36 impressed as C-48, C-48A, C-48B, and C-48C.

- C-48 - 1 impressed ex-United AirlinesDC-3A.

- C-48A - 3 impressed DC-3As with 18-seat interiors.

- C-48B - 16 impressed ex-United Airlines DST-Aair ambulanceswith 16-berth interiors.

- C-48C - 16 impressed DC-3As with 21-seat interiors.

- C-49

- Various DC-3 and DST models; 138 impressed into service as C-49, C-49A, C-49B, C-49C, C-49D, C-49E, C-49F, C-49G, C-49H, C-49J, and C-49K.

- C-50

- Various DC-3 models, fourteen impressed as C-50, C-50A, C-50B, C-50C, and C-50D.

- C-51

- One impressed aircraft originally ordered by Canadian Colonial Airlines, had starboard-side door.

- C-52

- DC-3A aircraft with R-1830 engines, five impressed as C-52, C-52A, C-52B, C-52C, and C-52D.

- C-68

- Two DC-3As impressed with 21-seat interiors.

- C-84

- One impressed DC-3B aircraft.

- Dakota II

- BritishRoyal Air Forcedesignation for impressed DC-3s.

- LXD1

- A single DC-3 supplied for evaluation by theImperial Japanese Navy Air Service(IJNAS).

- R4D-2

- Two Eastern Air Lines DC-3-388s impressed intoUnited States Navy(USN) service as VIP transports, later designatedR4D-2Fand laterR4D-2Z.

- R4D-4

- Ten DC-3As impressed for use by the USN.

- R4D-4R

- Seven DC-3s impressed as staff transports for the USN.

- R4D-4Q

- Radar countermeasures version of R4D-4 for the USN.

Conversions[edit]

- Dart-Dakota

- for BEA test services, powered by twoRolls-Royce Dartturboprop engines.

- Mamba-Dakota

- A single conversion for the Ministry of Supply, powered by twoArmstrong-Siddeley Mambaturboprop engines.

- Airtech DC-3/2000

- DC-3/C-47 engine conversion byAirtech Canada,first offered in 1987. Powered by twoPZL ASz-62ITradial engines.[51]

- Basler BT-67

- DC-3/C-47 conversion with a stretched fuselage, strengthened structure, modern avionics, and powered by twoPratt & Whitney Canada PT-6A-67Rturboprop engines.

- BSAS C-47TP Turbo Dakota

- A South African C-47 conversion for theSouth African Air Forceby Braddick Specialised Air Services, with two Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-65R turboprop engines, revised systems, stretched fuselage, and modern avionics.

- Conroy Turbo-Three

- One DC-3/C-47 converted byConroy Aircraftwith twoRolls-Royce Dart Mk. 510turboprop engines.

- Conroy Super-Turbo-Three

- Same as the Turbo Three but converted from a Super DC-3. One converted.

- Conroy Tri-Turbo-Three

- Conroy Turbo Three further modified by the removal of the two Rolls-Royce Dart engines and their replacement by three Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6s (one mounted on each wing and one in the nose).

- Greenwich Aircraft Corp Turbo Dakota DC-3

- DC-3/C-47 conversion with a stretched fuselage, strengthened wing center section, updated systems, and powered by two Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-65AR turboprop engines.[52][53]

- TS-62

- Douglas-built C-47s fitted with RussianShvetsov ASh-62radial engines after World War II due to shortage of American engines in the Soviet Union.[citation needed]Some TS-62s featured an small extra cockpit window on the left side.

- TS-82

- Similar to TS-62, but with 1650 hpShvetsov ASh-82radial engines.[citation needed]

- USAC DC-3 Turbo Express

- A turboprop conversion by the United States Aircraft Corporation, fittingPratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-45Rturboprop engines with an extended forward fuselage to maintain center of gravity. First flight of the prototype conversion, (N300TX), was on July 29, 1982.[54]

Military and foreign derivatives[edit]

- Douglas C-47 Skytrain and C-53 Skytrooper

- Production military DC-3A variants.

- Showa and Nakajima L2D

- Developments manufactured under license in Japan byNakajimaandShowafor the IJNAS; 487 built.

- Lisunov Li-2 and PS-84

- Developments manufactured under license in theUSSR;4,937 built.

Accidents and incidents[edit]

Specifications (DC-3A-S1C3G)[edit]

Data fromMcDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920[1]

General characteristics

- Crew:two

- Capacity:21–32 passengers

- Length:64 ft 5 in (19.7 m)

- Wingspan:95 ft 0 in (29.0 m)

- Height:16 ft 9 in (5.16 m) (level attitude) 23 ft 6 in

- Wing area:987 sq ft (91.7 m2)

- Aspect ratio:9.17

- Airfoil:NACA2215 / NACA2206

- Empty weight:16,865 lb (7,650 kg)

- Gross weight:25,200 lb (11,431 kg) payload w/full fuel, 3,446 lb

- Fuel capacity:822 gal. (3736 L)

- Powerplant:2 ×Pratt & Whitney R-1830-S1C3G Twin Wasp14-cyl. air-cooled two row radial piston engine, 1,200 hp (890 kW) each

- Propellers:3-bladedHamilton Standard 23E50series, 11 ft 6 in (3.5 m) diameter hydraulically controlled constant speed, feathering

Performance

- Maximum speed:223 kn (257 mph, 413 km/h) at 8,500 ft (2,590 m)

- Cruise speed:183 kn (211 mph, 339 km/h)

- Stall speed:68.0 kn (78.2 mph, 125.9 km/h)

- Never exceed speed:223 kn (257 mph, 413 km/h)

- Minimum control speed:77 kn (89 mph, 143 km/h) with one engine inoperative

- Range:1,370 nmi (1,580 mi, 2,540 km) (maximum fuel, 3500 lb payload), cruise speed/range at 10,000 ft ASL, cruise fuel consumption of 94 gph at 50% power, 157kt IAS, 1,740 nm

- Service ceiling:23,200 ft (7,100 m), with one engine operative, 9,000 ft

- Rate of climb:1,140 ft/min (5.8 m/s), rate of climb at sea level with one engine operative, 200 fpm

- Wing loading:25.5 lb/sq ft (125 kg/m2)

- Power/mass:0.0952 hp/lb (156.5 W/kg)[55]

Notable appearances in media[edit]

An attraction for the cityTaupōinNew Zealand,is aMcDonald'soutlet, where a decommissioned model is attached to the store. There is dine-in seating available in the plane.[56]

See also[edit]

Related development

- Basler BT-67

- Douglas AC-47 Spooky

- Douglas C-47 Skytrain

- Douglas R4D-8/C-117D

- Douglas DC-2

- Lisunov Li-2

- Showa/Nakajima L2D

- Conroy Turbo-Three

- Conroy Tri-Turbo-Three

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Boeing 247

- Curtiss C-46 Commando

- Douglas DC-5

- Focke-Wulf Fw 206

- Junkers Ju 52

- Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar

- Saab 90 Scandia

- Vickers VC.1 Viking

Related lists

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^abFrancillon 1979, pp. 217–251.

- ^"Douglas DC-3 and C-47 Engines".The Dakota Association of South Africa.RetrievedApril 10,2023.

- ^Kathleen Burke (April 2013)."How the DC-3 Revolutionized Air Travel".Smithsonian.

- ^"Boeing: Historical Snapshot: DC-3 Commercial Transport".boeing.Archived fromthe originalon June 4, 2023.RetrievedDecember 10,2020.

- ^"Douglas DC-3 | National Air and Space Museum".airandspace.si.edu.RetrievedApril 21,2024.

- ^Jonathan Glancey(October 9, 2013)."The Douglas DC-3: Still revolutionary in its 70s".BBC.

- ^"Why the DC-3 is such a Badass Plane".Eric Tegler, Popular Mechanics, August 8, 2017.RetrievedAugust 22,2020.

- ^"The plane that won't quit: celebrating the Douglas DC-3".The Garden of Memory.December 18, 2023.RetrievedDecember 24,2023.

- ^O'Leary 1992, p. 7.

- ^May, Joseph (January 8, 2013)."Flagship Knoxville — an American Airlines Douglas DC-3".Seattle Post-Intelligencer blogs. Archived fromthe originalon October 10, 2017.RetrievedAugust 3,2014.

- ^Berths were 77 in (2.0 m) long; lowers were 36 in (910 mm) wide and uppers were 30 in (760 mm).

- ^Pearcy 1987, p. 17.

- ^O'Leary 2006, p. 54.

- ^abGradidge 2006, p. 20.

- ^Pearcy 1987, p. 76

- ^Pearcy 1987, pp. 69–117

- ^Turbo Dakota DC-3 "Turbine Conversion Aircraft".dodson. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^"FAA Supplemental Type Certificate Number SA3820SW"ArchivedDecember 28, 2016, at theWayback Machineretrieved March 28, 2015

- ^Turbo Dakota DC-3 Conversion ProcessArchived2014-09-26 at theWayback Machine,Dodson International. Retrieved March 28, 2015

- ^"Basler BT-67".Basler Turbo Conversions, LLC via baslerturbo, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^Turbine AircraftRetrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^Holden, Henry."The DC-3 Genesis of The Legend".dc3history.org. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ab"DC-3".Flagship Detroit Foundation. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^"CNAC'S DC-2 1/2"Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^Gradidge 2006, p. 15.

- ^Norton, Bill (2004).Air War on the Edge: A History of the Israeli Air Force and Its Aircraft Since 1947.Midland. p. 99.ISBN9781857800883.

- ^FlightGlobal archive (April 18, 1953)

- ^FlightGlobal archive (November 14, 1946)

- ^"Douglas DC-3 Dakota".UK Heritage Aviation Trust.Archived fromthe originalon December 24, 2019.RetrievedNovember 9,2019.

- ^"The Seventies 1970–1980: C-117, p. 316".Archived2013-05-13 at theWayback Machinehistory.navy.mil.Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^Gradidge 2006, pp. 634–637.

- ^Gabbert, Bill (December 21, 2015)."The last Forest Service DC-3 retires".RetrievedMarch 7,2020.

- ^Holden 1991, p. 145

- ^Glancey, Jonathan (October 10, 2013)."The Douglas DC-3: Still Revolutionary in its 70s".BBC.RetrievedJanuary 21,2017.

- ^"Colombia's Workhorse, the DC-3 airplane".The Washington Post.RetrievedMarch 15,2012.

- ^"Douglas DC-3".Buffalo Airways.Archived fromthe originalon January 18, 2013.RetrievedJanuary 1,2021.

- ^ Moss, Frank."World's Oldest DC-3".douglasdc3.RetrievedAugust 9,2011.

- ^"Sunshine Skies".facebook.Archived fromthe originalon February 26, 2022.RetrievedJune 23,2020.

- ^"N133D Flight Tracking and History".FlightAware.RetrievedJune 23,2020.

- ^Pearcy 1987 p. 22

- ^"The de Havilland Aircraft Co. Ltd".Flight,November 18, 1960, p. 798. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^"Sleeping Car of the Air Has Sixteen Sleeping Berths".Popular Mechanics,January 1936.

- ^"Aircraft Specifications NO. A-669".FAA.Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^Gradidge 2006, pp. 632–633.

- ^Gradidge, 2006, p. 634

- ^Pearcy, ArthurDouglas Propliners DC-1 – DC-7,Shrewsbury, England: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 1995,ISBN1-8531026-1-X,pp. 93–95.

- ^Gradidge 2006, pp. 634–639.

- ^Pearcy 1987, p. 34

- ^"Douglas C-41A".Archived2008-09-07 at theWayback Machineaero-web.org. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^Rickard, J. (November 11, 2008)."Douglas C-41A".historyofwar.org.RetrievedJune 8,2017.

- ^"AirTech Company Profile"ArchivedAugust 7, 2016, at theWayback Machine.ic.gc.ca. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^Turbo Dakota DC-3 Conversion ProcessArchived2014-09-26 at theWayback Machine,Dodson International. Retrieved January 4, 2013

- ^Specs – Engines & PropsArchived2013-04-13 at theWayback Machine,Dodson International. Retrieved January 4, 2013

- ^Taylor 1983[page needed]

- ^Accessed 6 October 2023,https:// aopa.org/news-and-media/all-news/1994/june/pilot/flying-the-dc-3

- ^lovetaupo, Love Taupo |."McDonald's Taupo".lovetaupo.RetrievedApril 9,2024.

Bibliography[edit]

- Francillon, René.McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Since 1920: Volume I.London: Putnam, 1979.ISBN0-87021-428-4.

- Gradidge, Jennifer M.The Douglas DC-1/DC-2/DC-3: The First Seventy Years, Volumes One and Two.Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd., 2006.ISBN0-85130-332-3.

- Holden, Henry M..The Douglas DC-3.Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania: TAB Books, 1991.ISBN0-8306-3450-9.

- Kaplan, Philip.Legend: A Celebration of the Douglas DC-3/C-47/Dakota.Peter Livanos & Philip Kaplan, 2009.ISBN978-0-9557061-1-0.

- Key Publishing (2023).Lockheed Constellation.Historic Commercial Aircraft Series, Vol 13. Stamford, Lincs, UK: Key Publishing.ISBN9781802823707.

- O'Leary, Michael.DC-3 and C-47 Gooney Birds.St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1992.ISBN0-87938-543-X.

- O'Leary, Michael.When Fords Ruled the Sky (Part Two).Air Classics,Volume 42, No. 5, May 2006.

- Pearcy, Arthur.Douglas DC-3 Survivors, Volume 1.Bourne End, Bucks, UK: Aston Publications, 1987.ISBN0-946627-13-4.

- Pearcy, Arthur.Douglas Propliners: DC-1–DC-7.Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1995.ISBN1-85310-261-X.

- Reinhard, Martin A. (January–February 2004). "Talkback".Air Enthusiast.No. 109. p. 74.ISSN0143-5450.

- Taylor, John W. R.Jane's All the World's Aircraft, 1982–83.London: Jane's Publishing Company, 1983.ISBN0-7106-0748-2.

- Wulf, Herman de (August–November 1990). "An Airline at War".Air Enthusiast(13): 72–77.ISSN0143-5450.

- Yenne, Bill.McDonnell Douglas: A Tale of Two Giants.Greenwich, Connecticut: Bison Books, 1985.ISBN0-517-44287-6.