Drake Passage

TheDrake Passagealso known asHoces Sea,is the body of water between South America'sCape Horn,Chile, Argentina, and theSouth Shetland IslandsofAntarctica.It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean (Scotia Sea) with the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean and extends into theSouthern Ocean.The passage is named after the 16th-century English explorer and privateerSir Francis Drake.

The Drake Passage is considered one of the most treacherous voyages for ships to make. Currents at its latitude meet no resistance from any landmass, and waves top 40 feet (12 m), giving it a reputation for being "the most powerful convergence of seas".[1]

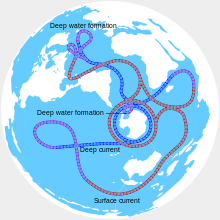

As the Drake Passage is the narrowest passage (choke point) around Antarctica, its existence and shape strongly influence the circulation of water around Antarctica and theglobal oceanic circulation,as well as the global climate. Thebathymetryof the Drake Passage plays an important role in the global mi xing of oceanic water.

History[edit]

In 1525, Spanish navigatorFrancisco de Hocesdiscovered the Drake Passage while sailing south from the entrance of theStrait of Magellan.[2]Because of this, the Drake Passage is referred to as the"Mar de Hoces (Sea of Hoces)"inSpanishmaps and sources, while almost always in the rest of theSpanish-speaking countriesit is mostly known as “Pasaje de Drake” (Argentina, mainly), “Paso Drake” or “Mar de Drake” (Chile, mainly).

The passage received its English name fromSir Francis Drakeduringhis raiding expedition.After passing in 1578 through the Strait of Magellan withMarigold,Elizabeth,and hisflagshipGolden Hind,Drake entered the Pacific Ocean and was blown far south in a tempest.Marigoldwas lost andElizabethabandoned the fleet. Only Drake'sGolden Hindentered the passage.[3]This incident demonstrated to the English that there was open water south of South America.[4]

In 1616, Dutch navigatorWillem Schoutenbecame the first to sail aroundCape Hornand through the Drake Passage.[5]

On December 25, 2019, a crew of six explorers successfully rowed across the passage, becoming the first in history to do so.[6]This accomplishment became the subject of a 2020 documentary,The Impossible Row.[7]

Geography[edit]

The Drake Passage opened when Antarctica separated from South America due toplate tectonics,however, there is much debate about when this occurred, with estimates ranging from 49 to 17 million years ago (Ma).[8][9]

The opening had a major effect on the global oceans due to deep currents like theAntarctic Circumpolar Current(ACC). This opening could have been a primary cause of changes in global circulation and climate, as well as the rapid expansion ofAntarctic ice sheets,because, as Antarctica was encircled by ocean currents, it was cut off from receiving heat from warmer regions.[10]

The 800-kilometre-wide (500 mi) passage betweenCape HornandLivingston Islandis the shortest crossing from Antarctica to another landmass. The boundary between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans is sometimes taken to be a line drawn from Cape Horn toSnow Island(130 kilometres (81 mi) north of mainland Antarctica), though theInternational Hydrographic Organizationdefines it as the meridian that passes through Cape Horn: 67° 16′ W.[11]Both lines lie within the Drake Passage.

The other two passages around the southern extremity of South America — theStrait of Magellanand theBeagle Channel— have frequentnarrows,leaving little maneuvering room for a ship, as well as unpredictable winds and tidal currents. Most sailing ships thus prefer the Drake Passage, which is open water for hundreds of miles.

No significant land sits at the latitudes of the Drake Passage. This is important to the unimpeded eastward flow of theAntarctic Circumpolar Current,which carries a huge volume of water through the passage and around Antarctica.

The passage hosts whales, dolphins, andseabirdsincludinggiant petrels,otherpetrels,albatrosses,andpenguins.

Importance in physical oceanography[edit]

The presence of the Drake Passageway allows the three main ocean basins (Atlantic, Pacific and Indian) to be connected via theAntarctic Circumpolar current(ACC), the strongest oceanic current, with an estimated transport of 100–150 Sv (Sverdrups,million m3/s). This flow is the only large-scale exchange occurring between the global oceans, and the Drake passage is the narrowest passage on its flow around Antarctica. As such, a significant amount of research has been done in understanding how the shape of the Drake passage (bathymetryand width) affects the global climate.

Oceanic and climate interactions[edit]

Major features of the modern ocean’s temperature and salinity fields, including the overall thermal asymmetry between the hemispheres, the relative saltiness of deep water formed in the northern hemisphere, and the existence of a transequatorial conveyor circulation, develop after Drake Passage is opened.[12]

The importance of an open Drake Passage extends farther than theSouthern Oceanlatitudes. TheRoaring Fortiesand the Furious Fifties blow around Antarctica and drive theAntarctic Circumpolar Current(ACC). As a result ofEkman Transport,water gets transported northward from the ACC (on the left-hand side while facing the stream direction). Using aLagrangian approach,water parcels passing through the Drake Passage can be followed in their journey in the oceans. Around 23 Sv of water is transported from the Drake Passage to the equator, mainly in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.[13]This value is not far from theGulf Streamtransport in theFlorida Strait(33 Sv[14]), but is an order of magnitude lower than the transport of the ACC (100–150 Sv). Water transported from the Southern Ocean to the Northern Hemisphere contributes to the globalmass balanceand permits themeridional circulationacross the oceans.

Several studies have linked the current shape of the Drake Passage to an effectiveAtlantic meridional overturning circulation(AMOC). Models have been run with different widths and depths of the Drake Passage, and consequent changes in the global oceanic circulation and temperature distribution have been analyzed:[12][15]It appears that the "conveyor belt" of the globalthermohaline circulationappears only in presence of an open Drake Passage, subject towind forcing.[12]With a closed Drake Passage, there is noNorth Atlantic Deep Water(NADW) cell, and no ACC. With a shallower Drake Passage, a weak ACC appears, but still no NADW cell.[15]

It has also been shown that present-day distribution ofdissolved inorganic carboncan be obtained only with an open Drake Passage.[16]

Regarding theglobal surface temperature,an open (and sufficiently deep) Drake Passage cools the Southern Ocean and warms the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. The isolation of Antarctica by the ACC (that can flow only with an open Drake Passage) is credited by many researchers with causing the glaciation of the continent and global cooling in theEoceneepoch.

Turbulence and mi xing[edit]

Diapycnal mi xingis the process by which different layers of astratified fluidmix. It directly affects vertical gradients, thus it is of great importance to all gradient-driven types of transport and circulation (includingthermohaline circulation). Mi xing drives the global thermohaline circulation; without internal mi xing, cooler water would never rise above warmer water, and there would be no density (buoyancy)-driven circulation. However, mi xing in the interior of most of the ocean is thought to be ten times weaker than required to support the global circulation.[17][18][19]It has been hypothesised that the extra-mi xing can be ascribed to breaking ofinternal waves(Lee waves).[20]When a stratified fluid reaches an internal obstacle, a wave is created that can eventually break, mi xing the fluid's layers. It has been estimated that thediapycnal diffusivityin the Drake Passage is ~20 times the value immediately to the west in the Pacific sector of theAntarctic Circumpolar Current(ACC).[18]Much of the energy that is dissipated through internal wave breaking (around 20% of the wind energy put into the ocean) is dissipated in the Southern Ocean.[21]

In short, without the coarse topography in the depths of the Drake Passage, oceanic internal mi xing would be weaker, and the global circulation would be affected.

Historical importance in oceanographic observations[edit]

Worldwide satellite measurements of oceanic properties have been available since the 1980s. Before then, data could be only gathered through oceanic ships taking direct measurements. TheAntarctic Circumpolar Current(ACC) has been (and is) surveyed making repeated transects. South America and theAntarctic Peninsulaconstrain the ACC in the Drake Passage; the convenience of measuring the ACC across the passage lays in the clear boundaries of the current in that stripe. Even after the advent ofsatellite altimetrydata, direct observations in the Drake Passage have not lost their exceptionality. The relative shallowness and narrowness of the passage makes it particularly suitable to assess the validity of horizontallyandvertically changing quantities (such as velocity inEkman's theory[22]).

In addition, the strength of the ACC makes meanders and pinchingcold-core cyclonic ringseasier to observe.[23]

Fauna[edit]

Wildlife in the Drake Passage includes the following species:

Birds[edit]

- Sooty shearwater

- White-chinned petrel

- Southern giant petrel

- Northern giant-petrel

- Black-browed albatross

- Campbell albatross

- Grey-headed albatross

- Atlantic yellow-nosed albatross

- Indian yellow-nosed albatross

- Buller's albatross

- Salvin's albatross

- Shy albatross

- Southern royal albatross

- Northern royal albatross

- Wandering albatross

- Light-mantled albatross

- Sooty albatross

- Great shearwater

- Great-winged petrel

- Kerguelen petrel

- Southern fulmar

- Cape petrel

- Soft-plumaged petrel

- White-headed petrel

- Atlantic petrel

- Grey petrel

- Antarctic prion

- Slender-billed prion

- Blue petrel

- Black-bellied storm petrel

- Wilson's storm-petrel

Cetaceans[edit]

Gallery[edit]

-

Rough seas are common in the Drake Passage

-

Tourists watch whales in the Drake Passage

-

Seabird (light-mantled sooty albatross) flying over the Drake Passage

-

Humpback whalesare a common sight in the Drake Passage

-

Hourglass dolphinsleaping in the Passage

-

Drake Passage orMar de HocesbetweenSouth AmericaandAntarctica

-

Drake Passage

See also[edit]

- Elizabeth Island (Cape Horn)

- Garcia de Nodal expedition

- Bransfield Strait

- Sars Bank

- Timeline of Francis Drake's circumnavigation

References[edit]

- ^"6 men become 1st to cross perilous Drake Passage unassisted".AP NEWS.Associated Press.2019-12-28.Retrieved2020-10-30.

- ^Oyarzun, Javier,Expediciones españolas al Estrecho de Magallanes y Tierra de Fuego,1976, Madrid: Ediciones Cultura HispánicaISBN978-84-7232-130-4

- ^Sugden, John (2006).Sir Francis Drake.London: Pimlico. p. 46.ISBN978-1-844-13762-6.

- ^Martinic B., Mateo(2019)."Entre el mito y la realidad. La situación de la misteriosa Isla Elizabeth de Francis Drake"[Between myth and reality. The situation of the mysterious Elizabeth Island of Francis Drake].Magallania(in Spanish).47(1): 5–14.doi:10.4067/S0718-22442019000100005.

- ^Quanchi, Max (2005).Historical dictionary of the discovery and exploration of the Pacific islands.Lanham, Md.:Scarecrow Press.ISBN0810853957.

- ^"Impossible Row team achieve first ever row across the Drake Passage".Guinness World Records.2019-12-27.Retrieved2020-03-10.

- ^"'The Impossible Row'. Historic first row of the Southern Ocean ".World Rowing.17 January 2020.

- ^Scher, Howie D.; Martin, Ellen E. (21 April 2006)."Timing and Climatic Consequences of the Opening of Drake Passage".Science.312(5772): 428–430.Bibcode:2006Sci...312..428S.doi:10.1126/science.1120044.PMID16627741.S2CID19604128.

- ^van de Lagemaat, Suzanna H.A.; Swart, Merel L.A.; Vaes, Bram; Kosters, Martha E.; Boschman, Lydian M.; Burton-Johnson, Alex; Bijl, Peter K.; Spakman, Wim; van Hinsbergen, Douwe J.J. (April 2021)."Subduction initiation in the Scotia Sea region and opening of the Drake Passage: When and why?".Earth-Science Reviews.215:103551.Bibcode:2021ESRv..21503551V.doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103551.hdl:20.500.11850/472835.S2CID233576410.

- ^Livermore, Roy; Hillenbrand, Claus-Dieter; Meredith, Mik e; Eagles, Graeme (2007)."Drake Passage and Cenozoic climate: An open and shut case?".Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems.8(1): n/a.Bibcode:2007GGG.....8.1005L.doi:10.1029/2005GC001224.ISSN1525-2027.

- ^International Hydrographic Organization,Limits of Oceans and Seas,Special Publication No. 28, 3rd edition, 1953[1]Archived2011-10-08 at theWayback Machine,p.4

- ^abcToggweiler, J. R.; Bjornsson, H. (2000)."Drake Passage and palaeoclimate".Journal of Quaternary Science.15(4): 319–328.Bibcode:2000JQS....15..319T.doi:10.1002/1099-1417(200005)15:4<319::AID-JQS545>3.0.CO;2-C.ISSN1099-1417.

- ^Friocourt, Yann; Drijfhout, Sybren; Blanke, Bruno; Speich, Sabrina (2005-07-01)."Water Mass Export from Drake Passage to the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans: A Lagrangian Model Analysis".Journal of Physical Oceanography.35(7): 1206–1222.Bibcode:2005JPO....35.1206F.doi:10.1175/JPO2748.1.ISSN1520-0485.

- ^Heiderich, Joleen; Todd, Robert E. (2020-08-01)."Along–Stream Evolution of Gulf Stream Volume Transport".Journal of Physical Oceanography.50(8): 2251–2270.Bibcode:2020JPO....50.2251H.doi:10.1175/JPO-D-19-0303.1.hdl:1912/26689.ISSN0022-3670.S2CID219927256.

- ^abcSijp, Willem P.; England, Matthew H. (2004-05-01)."Effect of the Drake Passage Throughflow on Global Climate".Journal of Physical Oceanography.34(5): 1254–1266.Bibcode:2004JPO....34.1254S.doi:10.1175/1520-0485(2004)034<1254:EOTDPT>2.0.CO;2.ISSN0022-3670.

- ^Fyke, Jeremy G.; D'Orgeville, Marc; Weaver, Andrew J. (May 2015)."Drake Passage and Central American Seaway controls on the distribution of the oceanic carbon reservoir".Global and Planetary Change.128:72–82.Bibcode:2015GPC...128...72F.doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2015.02.011.OSTI1193435.

- ^Munk, Walter H. (August 1966)."Abyssal recipes".Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts.13(4): 707–730.Bibcode:1966DSRA...13..707M.doi:10.1016/0011-7471(66)90602-4.

- ^abWatson, Andrew J.; Ledwell, James R.; Messias, Marie-José; King, Brian A.; Mackay, Neill; Meredith, Michael P.; Mills, Benjamin; Naveira Garabato, Alberto C. (2013-09-19)."Rapid cross-density ocean mi xing at mid-depths in the Drake Passage measured by tracer release".Nature.501(7467): 408–411.Bibcode:2013Natur.501..408W.doi:10.1038/nature12432.ISSN0028-0836.PMID24048070.S2CID1624477.

- ^Ledwell, James R.; Watson, Andrew J.; Law, Clifford S. (August 1993)."Evidence for slow mi xing across the pycnocline from an open-ocean tracer-release experiment".Nature.364(6439): 701–703.Bibcode:1993Natur.364..701L.doi:10.1038/364701a0.ISSN0028-0836.S2CID4235009.

- ^Nikurashin, Maxim; Ferrari, Raffaele (2010-09-01)."Radiation and Dissipation of Internal Waves Generated by Geostrophic Motions Impinging on Small-Scale Topography: Application to the Southern Ocean".Journal of Physical Oceanography.40(9): 2025–2042.Bibcode:2010JPO....40.2025N.doi:10.1175/2010JPO4315.1.ISSN1520-0485.S2CID1681960.

- ^Nikurashin, Maxim; Ferrari, Raffaele (June 2013)."Overturning circulation driven by breaking internal waves in the deep ocean".MIT Web Domain.40(12).Massachusetts Institute of Technology:3133.Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.3133N.doi:10.1002/grl.50542.hdl:1721.1/85568.S2CID16754887.

- ^Polton, Jeff A.; Lenn, Yueng-Djern; Elipot, Shane; Chereskin, Teresa K.; Sprintall, Janet (2013-08-01)."Can Drake Passage Observations Match Ekman's Classic Theory?".Journal of Physical Oceanography.43(8): 1733–1740.Bibcode:2013JPO....43.1733P.doi:10.1175/JPO-D-13-034.1.ISSN0022-3670.S2CID129749697.

- ^Joyce, T.M.; Patterson, S.L.; Millard, R.C. (November 1981)."Anatomy of a cyclonic ring in the drake passage".Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers.28(11): 1265–1287.Bibcode:1981DSRA...28.1265J.doi:10.1016/0198-0149(81)90034-0.

- ^Lowen, James (2011).Antarctic Wildlife: A Visitor's Guide.Princeton:Princeton University Press.pp. 44–49, 112–158.ISBN978-0-691-15033-8.