Dreadlocks

Dreadlocks,also known asdreadsorlocs,are a hairstyle made of rope-like strands of hair. This is done by not combing the hair and allowing it to mat naturally or by twisting it manually. Over time, the hair will form tight braids or ringlets.[1][2]

Etymology

[edit]

The history of the name "dreadlocks" is unclear. Some authors trace the term to theRastafarians,a group of whom apparently coined it in 1959 as a reference to their"dread", or fear, of God.Rastafari developed in Jamaica in the 1930s, decades before theMau Mau rebellionemerged in Kenya. Byrd and Tharps write that the name "dredlocs" originated in the time of the slave trade: when transported Africans disembarked from the slave ships after spending months confined in unhygienic conditions, whites would report that their undressed and matted kinky hair was "dreadful". According to them it is due to these circumstances that many people wearing the style today drop the "a" in dreadlock to avoid negative implications.[3]

The word dreadlocks refers to matted locks of hair. Several different languages have names for these locks. InSanskritit isjaṭā,and inWolofit isndiagneandndjan,[4]InAkanit ismpesempese.InYorubait isdada.[5]InIgboit isezenwaandelena.[6]InHamerit isgoscha.[7]InShonait ismhotsi.[8]InNyanekait isnontombi.[9]

History

[edit]Africa

[edit]According to Sherrow inEncyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History,dreadlocks date back to ancient times in various cultures. Inancient Egypt,Egyptians wore locked hairstyles andwigsappeared onbas-reliefs,statuary and other artifacts.[10]Mummified remains of Egyptians with locked wigs have also been recovered from archaeological sites.[11]According to Maria Delongoria, braided hair was worn by people in theSahara desertsince 3,000 BC. Dreadlocks were also worn by followers ofAbrahamic religions.For example,Ethiopian CopticBahatowie priests adopted dreadlocks as a hairstyle before the fifth century AD (400 or 500 AD). Locking hair was practiced by some ethnic groups inEast,Central,West,andSouthernAfrica.[12][13][14]

Pre-Columbian Americas

[edit]Pre-ColumbianAztecpriests were described inAztec codices(including theDurán Codex,theCodex Tudelaand theCodex Mendoza) as wearing their hair untouched, allowing it to grow long and matted.[15]Bernal Diaz del Castillo records:

There were priests with long robes of black cloth... The hair of these priests was very long and so matted that it could not be separated or disentangled, and most of them had their ears scarified, and their hair was clotted with blood.

Hairstyles in Europe

[edit]

This section has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The earliest known possible depictions of dreadlocks date back as far as 1600–1500 BCE in theMinoan Civilization,centered inCrete(now part ofGreece).[17]Frescoesdiscovered on theAegean islandofThera(modernSantorini,Greece) portray individuals with long braided hair or long dreadlocks.[16][22][23][24]Another source describes the hair of the boys in theAkrotiri Boxer Frescoas long tresses, not dreadlocks. Tresses of hair are defined byCollins Dictionaryas braided hair, braided plaits, or long loose curls of hair.[25][26][27]

Nineteenth century

[edit]

In what is now Poland, for about a thousand years, some people wore a matted hairstyle similar to that of someIranicScythians.Zygmunt Glogerin hisEncyklopedia staropolskamentions that thePolish plait(plica polonica) hairstyle was worn by some people in thePinskregion and theMasoviaregion at the beginning of the 19th century. The Polish plait can vary between one large plait and multiple plaits that resemble dreadlocks.[28]Polish plaits according to historical records were often infested withlice.It was believed that not washing and combing the hair would protect a person from diseases. This folk belief was sometimes common inEastern Europe.[29]

InSenegal,the Baye Fall, followers of theMouridemovement, a Sufi movement ofIslamfounded in 1887 AD byShaykh Aamadu Bàmba Mbàkke,are famous for growing dreadlocks and wearing multi-colored gowns.[30]

Cheikh Ibra Fall,founder of the Baye Fall school of theMouride Brotherhood,popularized the style by adding a mystic touch to it. This sect of Islam in Senegal, where Muslims wearndjan(dreadlocks), aimed to Africanize Islam. Dreadlocks to this group of Islamic followers symbolize their religious orientation.[31][32]Jamaican Rastas also reside in Senegal and have settled in areas near Baye Fall communities. Baye Fall and Jamaican Rastas have similar cultural beliefs regarding dreadlocks. Both groups wear knitted caps to cover their locs and wear locs for religious and spiritual purposes.[33]Male members of the Baye Fall religion wear locs to detach from mainstream Western ideals.[34]

Twentieth century into present day

[edit]

In the 1970s in the United States and Britain, Americans and British people attended reggae concerts. This resulted in Americans and British people being exposed to Jamaican culture, including Rastafarians wearing locs.Hippiesrelated to the Rastafarian idea of rejectingcapitalismandcolonialism,symbolized by the name "Babylon".One of the ways Rastafarians rejected Babylon was by wearing their hair naturally in locs to defy Western standards of beauty. The 1960s was the height of thecivil rights movementin the US, and some White Americans joined Black people in the fight against inequality andsegregationand were inspired by Black culture. As a result, some White people joined the Rastafarian movement. Dreadlocks were not a common hairstyle in the United States, but by the 1970s, some White Americans were inspired by reggae music, the Rastafarian movement, andAfrican-American hair cultureand started wearing dreadlocks.[35][36]According to authors Bronner and Dell Clark, the clothing styles worn by hippies in the 1960s and 1970s were copied fromAfrican-American culture.The word hippie comes from theAfrican-American slangwordhip.African-American dress and hairstyles such as braids (often decorated with beads), dreadlocks, and language were copied (appropriated) by hippies and developed into a new countercultural movement used by hippies.[37][38]

In Europe in the 1970s, hundreds of Jamaicans and otherCaribbean peopleimmigrated to metropolitan centers of London,Birmingham,Paris, and Amsterdam. Communities ofJamaicans,Caribbeans,and Rastas emerged in these areas. Thus Europeans in these metropolitan cities were introduced to Black cultures from the Caribbean and Rastafarian practices and were inspired byCaribbean culture,leading some of them to adopt Black hair culture, music, and religion. However, the strongest influence of Rastafari religion is amongEurope's Black population.[39][40]

Whenreggae music,which espoused Rastafarian ideals, gained popularity and mainstream acceptance in the 1970s, thanks toBob Marley's music and cultural influence, dreadlocks (often called "dreads" ) became a notable fashion statement worldwide, and have been worn by prominent authors, actors, athletes, and rappers.[41][42]Rastafari influenced its members worldwide to embrace dreadlocks. Black Rastas loc their hair to embrace their African heritage and accept African features as beautiful, such as dark skin tones, Afro-textured hair, and African facial features.[43]

Hip Hopandrapartists such asLauryn Hill,Lil Wayne,T-Pain,Snoop Dog,J-Cole,Wiz Khalifa,Chief Keef,Lil Jon,and other artists wear dreadlocks, which further popularized the hairstyle in the 1990s, early 2000s, and present day. Dreadlocks are a part of hip-hop fashion and reflect Black cultural music of liberation and identity.[44][45][46][47]Many rappers andAfrobeatartists inUgandawear locs, such asNavio,Delivad Julio,Fik Fameica,Vyper Ranking, Byaxy, Liam Voice, and other artists. From reggae music to hip hop, rap, and Afrobeat, Black artists in theAfrican diasporawear locs to display their Black identity and culture.[48][49][50]

Youth in Kenya who are fans of rap and hip hop music, and Kenyan rappers and musicians, wear locs to connect to the history of theMau Mau freedom fighterswho wore locs as symbols of anti-colonialism, and to Bob Marley, who was a Rasta.[51]Hip hop and reggae fashion spread toGhanaand fused with traditional Ghanaian culture.Ghanaian musicianswear dreadlocks incorporating reggae symbols and hip hop clothes mixed with traditional Ghanaian textiles, such as wearingGhanaian headwrapsto hold their locs.[52][53]Ghanaian women wear locs as a symbol of African beauty. The beauty industry in Ghana believe locs are a traditional African hair practice and market hair care products to promote natural African hairstyles such as afros and locs.[54]The previous generations of Black artists have inspired younger contemporary Black actresses to loc their hair, such asChloe Bailey,Halle Bailey,andR&BandPop musicsingerWillow Smith.More Black actors in Hollywood are choosing to loc their hair to embrace their Black heritage.[55]

Although more Black women in Hollywood and the beauty and music industries are wearing locs, there has never been a BlackMiss Americawinner with locs because there is pushback in the fashion industry towards Black women's natural hair. For example, modelAdesuwa Aighewilocked her hair and was told she might not receive any casting calls because of her dreadlocks. Some Black women in modeling agencies are forced to straighten their hair. However, more Black women are resisting and choosing to wear Black hairstyles such as afros and dreadlocks in fashion shows and beauty pageants.[56][57]For example, in 2007 Miss Universe Jamaica and Rastafarian,Zahra Redwood,was the first Black woman to break the barrier on a world pageant stage when she wore locs, paving the way and influencing other Black women to wear locs in beauty pageants. In 2015,Miss Jamaica WorldSanneta Myrie was the first contestant to wear locs to theMiss World Pageant.[58]In 2018,Dee-Ann Kentish-Rogersof Britain was crowned Miss Universe wearing her locs and became the first Black British woman to win the competition with natural locs.[59][60]

Hollywood cinemaoften uses the dreadlock hairstyle as a prop in movies for villains and pirates. According to author Steinhoff, this appropriates dreadlocks and removes them from their original meaning of Black heritage to one of dread and otherness. In the moviePirates of the Caribbean,the pirate Jack Sparrow wears dreadlocks. Dreadlocks are used in Hollywood to mystify a character and make them appear threatening or living a life of danger. In the movieThe Curse of the Black Pearl,pirates were dressed in dreadlocks to signify their cursed lives.[61]

Hairstyles at Burning Man

[edit]In the 1980s, artists and community organizers gathered together to celebrate freedom of expression through art calledBurning ManatBaker Beachin San Francisco, California. Burning Man started as a bonfiresummer solsticeritual. Over the years, participation in this event grew into the thousands. The location of Burning Man moved from Baker Beach toBlack Rock Desert, Nevada.Most of the attendants at Burning Man are White.Anthropologistsand historians who studied Burning Man argue that White people at Burning ManappropriateBlack and Native American culture in dress and hairstyles, such as Native American headdresses and dreadlocks.[62][63][64][65]

Some authors argue that the appropriation of dreadlocks was taken out of its original historical and cultural context of resisting oppression, having a Black identity, Black unity, a symbol of Black liberation and African beauty, and its spiritual meaning in other cultures to one of entertainment, a commodity, and a "fashion gadget."[66][67][68]In response to the backlash from the Black community about concerns of cultural appropriation from fashion creators putting fake dreadlocks on fashion models, in 2016 the modeling agency Assembly New York hired Black men with natural dreadlocks to model the hairstyle in a fashion show atNew York Fashion Week.[69]

By culture

[edit]Locks (like braids and plaits) have been worn for various reasons in many cultures and ethnic groups around the world throughout history. Their use has also been raised in debates aboutcultural appropriation.[70][71][72][73][74][75]

Africa

[edit]

The practice of wearing braids and dreadlocks in Africa dates back to 3,000 BC in the Sahara Desert. It has been commonly thought that other cultures influenced the dreadlock tradition in Africa. TheKikuyuandSomaliwear braided and locked hairstyles.[76][77]Warriors among theFulani,Wolof,andSererinMauritania,andMandinkainMaliwere known for centuries to have worncornrowswhen young and dreadlocks when old.

InWest Africa,the water spiritMami Watais said to have long locked hair. Mami Wata's spiritual powers of fertility and healing come from her dreadlocks.[78][79]West African spiritual priests calledDadawear dreadlocks to venerate Mami Wata in her honor as spiritual consecrations.[80]SomeEthiopianChristian monks and Bahatowie priests of theEthiopian Coptic Churchlock their hair for religious purposes.[81][82]InYorubaland,Aladura churchprophets calledwooliimat their hair into locs and wear long blue, red, white, or purple garments with caps and carry iron rods used as a staff.[83]Prophets lock their hair in accordance with the Nazarene vow in the Christian bible. This is not to be confused with the Rastafari religion that was started in the 1930s. The Aladura church was founded in 1925 andsyncretizesindigenous Yoruba beliefs about dreadlocks with Christianity.[84]Moses Orimolade Tunolasewas the founder of the first African Pentecostal movement started in 1925 in Nigeria. Tunolase wore dreadlocks and members of his church wear dreadlocks in his honor and for spiritual protection.[85]

TheYorubawordDadais given to children inNigeriaborn with dreadlocks.[86][87]SomeYoruba peoplebelieve children born with dreadlocks have innate spiritual powers, and cutting their hair might cause serious illness. Only the child's mother can touch their hair. "Dada children are believed to be young gods, they are often offered at spiritual altars for chief priests to decide their fate. Some children end up becoming spiritual healers and serve at the shrine for the rest of their lives." If their hair is cut, it must be cut by a chief priest and placed in a pot of water with herbs, and the mixture is used to heal the child if they get sick. Among theIgbo,Dada children are said to be reincarnatedJujuistsof great spiritual power because of their dreadlocks.[88][89]Children born with dreadlocks are viewed as special. However, adults with dreadlocks are viewed negatively. Yoruba Dada children's dreadlocks are shaved at a river, and their hair is grown back "tamed" and have a hairstyle that conforms to societal standards. The child continues to be recognized as mysterious and special.[90]It is believed that the hair of Dada children was braided in heaven before they were born and will bring good fortune and wealth to their parents. When the child is older, the hair is cut during a special ritual.[91]InYoruba mythology,theOrisha Yemojagave birth to a Dada who is a deified king in Yoruba.[92][93]However, dreadlocks are viewed in a negative light in Nigeria due to their stereotypical association with gangs and criminal activity; men with dreadlocks faceprofilingfrom Nigerian police.[94][95]

InGhana,among theAshanti people,Okomfo priestsare identified by their dreadlocks. They are not allowed to cut their hair and must allow it to mat and lock naturally. Locs are symbols of higher power reserved for priests.[96][97][98]Other spiritual people in Southern Africa who wear dreadlocks areSangomas.Sangomas wear red and white beaded dreadlocks to connect to ancestral spirits. Two African men were interviewed, explaining why they chose to wear dreadlocks. "One – Mr. Ngqula – said he wore his dreadlocks to obey his ancestors' call, given through dreams, to become a 'sangoma' in accordance with hisXhosa culture.Another – Mr. Kamlana – said he was instructed to wear his dreadlocks by his ancestors and did so to overcome 'intwasa', a condition understood in African culture as an injunction from the ancestors to become a traditional healer, from which he had suffered since childhood. "[99][100]InZimbabwe,there is a tradition of locking hair calledmhotsiworn by spirit mediums calledsvikiro.The Rastafarian religion spread to Zimbabwe and influenced some women inHarareto wear locs because they believe in the Rastafari's pro-Black teachings and rejection of colonialism.[101]

Maasaiwarriors inKenyaare known for their long, thin, red dreadlocks, dyed with red root extracts orred ochre(red earth clay).[102]TheHimba womeninNamibiaare also known for their red-colored dreadlocks. Himba women usered earth clay mixed with butterfatand roll their hair with the mixture. They use natural moisturizers to maintain the health of their hair.Hamar womeninEthiopiawear red-colored locs made using red earth clay.[103]InAngola,Mwila women create thick dreadlocks covered in herbs, crushed tree bark, dried cow dung, butter, and oil. The thick dreadlocks are dyed using oncula, an ochre of red crushed rock.[104][105][106]InSouthern,Eastern,andNorthernAfrica, Africans use red ochre as sunscreen and cover their dreadlocks and braids with ochre to hold their hair in styles and as a hair moisturizer by mi xing it with fats. Red ochre has a spiritual meaning of fertility, and in Maasai culture, the color red symbolizes bravery and is used in ceremonies and dreadlock hair traditions.[107][108]

Historians note that West and Central African people braid their hair to signify age, gender, rank, role in society, and ethnic affiliation. It is believed braided and locked hair provides spiritual protection, connects people to the spirit of the earth, bestows spiritual power, and enables people to communicate with the gods and spirits.[109][110][111]In the 15th and 16th centuries, theAtlantic slave tradesaw Black Africans forcibly transported fromSub-Saharan AfricatoNorth Americaand, upon their arrival in theNew World,their heads would be shaved in an effort to erase their culture.[112][113][114][115]Enslaved Africans spent months inslave shipsand their hair matted into dreadlocks that European slave traders called "dreadful."[116][117]

African diaspora

[edit]

In theAfrican diaspora,people loc their hair to have a connection to the spirit world and receive messages from spirits. It is believed locs of hair are antennas making the wearer receptive to spiritual messages.[118]Other reasons people loc their hair are for fashion and to maintain the health of natural hair, also calledkinky hair.[119]In the 1960s and 1970s in theUnited States,theBlack Power movement,Black is Beautifulmovement, and theNatural hair movementinspired manyBlack Americansto wear their hair natural inafros,braids,and locked hairstyles.[120][121]The Black is Beautiful cultural movement spread toBlack communities in Britain.In the 1960s and 1970s, Black people in Britain were aware of thecivil rights movementand other cultural movements in Black America and the social and political changes occurring at the time. The Black is Beautiful movement and Rastafari culture in Europe influenced Afro-Britons to wear their hair in natural loc styles and afros as a way to fight against racism, Western standards of beauty, and to develop unity among Black people of diverse backgrounds.[122][123]From the twentieth century to the present day, dreadlocks have been symbols of Black liberation and are worn by revolutionaries, activists,womanists,and radical artists in the diaspora.[124][125]For example, Black American literary authorToni Morrisonwore locs, andAlice Walkerwears locs to reconnect with their African heritage.[126]

Natural Black hairstyles worn by Black women are seen as not feminine and unprofessional in some American businesses.[127]Wearing locs in the diaspora signifies a person's racial identity and defiance of European standards of beauty, such as straight blond hair.[128]Locs encourage Black people to embrace other aspects of their culture that are tied to Black hair, such as wearing African ornaments like cowrie shells,beads,andAfrican headwrapsthat are sometimes worn with locs.[129][130]SomeBlack Canadianwomen wear locs to connect to theglobal Black culture.Dreadlocks unite Black people in the diaspora because wearing locs has the same meaning in areas of the world where there are Black people: opposing Eurocentric standards of beauty and sharing a Black and African diaspora identity.[131][132]For many Black women in the diaspora, locs are a fashion statement to express individuality and the beauty and versatility of Black hair. Locs are also aprotective hairstyleto maintain the health of their hair by wearing kinky hair in natural locs or faux locs. To protect their natural hair from the elements during thechanging seasons,Black women wear certain hairstyles to protect and retain the moisture in their hair. Black women wear soft locs as a protective hairstyle because they enclose natural hair inside them, protecting their natural hair from environmental damage. This protective soft loc style is created by "wrapping hair around the natural hair or crocheting pre-made soft locs into cornrows."[133]In the diaspora, Black men and women wear different styles of dreadlocks. Each style requires a different method of care. Freeform locs are formed organically by not combing the hair or manipulating the hair. There are also goddess locs, faux locs, sister locs, twisted locs, Rasta locs, crinkle locs, invisible locs, and other loc styles.[134][135][136]

Australia

[edit]

SomeIndigenous AustraliansofNorth Westand North Central Australia, as well as the Gold Coast region of Eastern Australia, have historically worn their hair in a locked style, sometimes also having long beards that are fully or partially locked. Traditionally, some wear the dreadlocks loose, while others wrap the dreadlocks around their heads or bind them at the back of the head.[137]In North Central Australia, the tradition is for the dreadlocks to be greased with fat and coated with red ochre, which assists in their formation.[138]In 1931 inWarburton Range,Western Australia, a photograph was taken of an Aboriginal Australian man with dreadlocks.[139]

In the 1970s, hippies from Australia's southern region moved toKuranda,where they introduced the Rastafari movement as expressed in thereggae musicofPeter ToshandBob Marleyto theBuluwaipeople in the 1970s. Aboriginal Australians found parallels between the struggles of Black people in theAmericasand their own racial struggles in Australia. Willie Brim, a Buluwai man born in the 1960s in Kuranda, identified with Tosh's and Marley's spiritually conscious music, and inspired particularly by Peter Tosh's albumBush Doctor,in 1978 he founded a reggae band calledMantakaafter the area alongside the Barron River where he grew up. He combined his people's cultural traditions with the reggae guitar he had played since he was young, and his band's music reflects Buluwai culture and history. Now a leader of the Buluwai people and a cultural steward, Brim and his band send an "Aboriginal message" to the world. He and other Buluwai people wear dreadlocks as a native part of their culture and not as an influence from the Rastafari religion. Although Brim was inspired by reggae music, he is not a Rastafarian as he and his people have their own spirituality.[140]Foreigners visiting Australia think the Buluwai people wearing dreadlocks were influenced by the Rastafarian movement, but the Buluwai say their ancestors wore dreadlocks before the movement began.[141]Some Indigenous Australians wear anAustralian Aboriginal flag(a symbol of unity and Indigenous identity in Australia) tied around their head to hold their dreadlocks.[142]

Buddhism/Hinduism

[edit]WithinTibetan Buddhismand other more esoteric forms of Buddhism, locks have occasionally been substituted for the more traditional shaved head. The most recognizable of these groups are known as theNgagpasofTibet.For Buddhists of these particular sects and degrees of initiation, their locked hair is not only a symbol of their vows but an embodiment of the particular powers they are sworn to carry.[143]Hevajra Tantra1.4.15 states that the practitioner of particular ceremonies "should arrange his piled up hair" as part of the ceremonial protocol.[144]Archeologists found a statue of a male deity,Shiva,with dreadlocks in Stung Treng province inCambodia.[145]In a sect of tantric Buddhism, some initiates wear dreadlocks.[146][147]The sect of tantric Buddhism in which initiates wear dreadlocks is calledweikzaandPassayanaorVajrayana Buddhism.Thissect of Buddhismis practiced in Burma. The initiates spend years in the forest with this practice, and when they return to the temples, they should not shave their heads to reintegrate.[148]

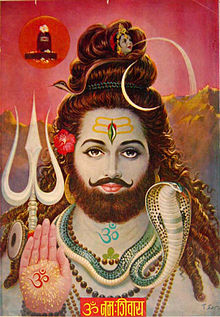

Hinduism

[edit]

The practice of wearing ajaṭā(dreadlocks) is observed in modern-day Hinduism,[150][151][152]most notably by sadhus who worshipShiva.[153][154]TheKapalikas,first commonly referenced in the6th century CE,were known to wear thejaṭā[155]as a form of deity imitation of thedevaBhairava-Shiva.[156]Shiva is often depicted with dreadlocks. According to Ralph Trueb, "Shiva's dreadlocks represent the potent power of his mind that enables him to catch and bind the unruly and wild rivergoddess Ganga."[157]

In a village inPune,Savitha Uttam Thorat, some women hesitate to cut their long dreadlocks because it is believed it will cause misfortune or bring down divine wrath. Dreadlocks practiced by the women in this region ofIndiaare believed to be possessed by the goddessYellamma.Cutting off the hair is believed to bring misfortune onto the woman, because having dreadlocks is considered to be a gift from the goddess Yellamma (also known as Renuka).[158]Some of the women have long and heavy dreadlocks that put a lot of weight on their necks, causing pain and limited mobility.[159][160]Some in local government and police in theMaharashtra regiondemand the women cut their hair, because the religious practice of Yellamma forbids women from washing and cutting their dreadlocks, causing health issues.[161]These locks of hair dedicated to Yellamma are calledjade,believed to be evidence of divine presence. However, in Southern India, people advocate for the end of the practice.[162] The goddessAngala Parameshvariin Indian mythology is said to havecataik-karimatted hair (dreadlocks). Women healers in India are identified by their locs of hair and are respected in spiritual rituals because they are believed to be connected to goddesses. A woman who has ajatais believed to derive her spiritual powers orshaktifrom her dreadlocks.[163]

Rastafari

[edit]

Rastafari movementdreadlocks are symbolic of theLion of Judah,and were inspired by theNazaritesof the Bible.[164]Jamaicans locked their hair after seeing images of Ethiopians with locs fighting Italian soldiers during theSecond Italo-Ethiopian War.The afro is the preferred hairstyle worn byEthiopians.During the Italian invasion, Ethiopians vowed not to cut their hair using the Biblical example of Samson, who got his strength from his seven locks of hair, until emperor Ras Tafari Makonnen (Haile Selassie) and Ethiopia were liberated and Selassie was returned from exile.[165]Scholars also state another indirect Ethiopian influence for Rastas locking their hair are the Bahatowie priests in Ethiopia and their tradition of wearing dreadlocks for religious reasons since the 5th century AD.[166]Another African influence for Rastas wearing locs was seeing photos ofMau Mau freedom fighterswith locs inKenyafighting against the British authorities in the 1950s. Dreadlocks to the Mau Mau freedom fighters were a symbol of anti-colonialism, and this symbolism of dreadlocks was an inspiration for Rastas to loc their hair in opposition to racism and promote an African identity.[167][168][169]The branch of Rastafari that was inspired to loc their hair after the Mau Mau freedom fighters was theNyabinghi Order,previously calledYoung Black Faith.Young Black Faith were considered a radical group of younger Rastafari members. Eventually, other Rastafari groups started locking their hair.[170]

In the Rastafarian belief, people wear locs for a spiritual connection to the universe and the spirit of the earth. It is believed that by shaking their locs, they will bring down the destruction ofBabylon.Babylon in the Rastafarian belief issystemic racism,colonialism, and any system of economic and social oppression of Black people.[171][172]Locs are also worn to defy European standards of beauty and help to develop a sense of Black pride and acceptance of African features as beautiful.[173][174]In another branch of Rastafari calledBoboshanti Order of Rastafari,dreadlocks are worn to display a black person's identity and social protest against racism.[175]The Bobo Ashanti are one of the strictestMansions of Rastafari.They cover their locs with brightturbansand wear long robes and can usually be distinguished from other Rastafari members because of this.[176]Other Rastas wear aRastacapto tuck their locs under the cap.[177]

TheBobo Ashanti( "Bobo" meaning "black" inIyaric;[178]and "Ashanti" in reference to theAshanti peopleofGhana,whom the Bobos claim are their ancestors),[179]were founded byEmmanuel Charles Edwardsin 1959 during the period known as the "groundation", where many protests took place calling for the repatriation of African descendants and slaves to Kingston. A Boboshanti branch spread to Ghana because of repatriated Jamaicans and other Black Rastas moving to Ghana. Prior to Rastas living in Ghana,GhanaiansandWest Africanspreviously had their own beliefs about locked hair. Dreadlocks in West Africa are believed to bestow children born with locked hair with spiritual power, and thatDadachildren, that is, those born with dreadlocks, were given to their parents bywater deities.Rastas and Ghanaians have similar beliefs about the spiritual significance of dreadlocks, such as not touching a person's or child's locs, maintaining clean locs, locs spiritual connections to spirits, and locs bestowing spiritual powers to the wearer.[180]

In sports

[edit]Dreadlocks have become a popular hairstyle among professional athletes. However, some athletes are discriminated against and were forced to cut their dreadlocks. For example, in December 2018, a Black high school wrestler in New Jersey was forced to cut his dreadlocks 90 seconds before his match, sparking a civil rights case that led to the passage of the CROWN Act in 2019.[181]

In professionalAmerican football,the number of players with dreadlocks has increased sinceAl HarrisandRicky Williamsfirst wore the style during the 1990s. In 2012, about 180National Football Leagueplayers wore dreadlocks. A significant number of these players are defensive backs, who are less likely to be tackled than offensive players. According to the NFL's rulebook, a player's hair is considered part of their "uniform", meaning the locks are fair game when attempting to bring them down.[182][183]

In theNBA,there has been controversy over Brooklyn Nets guardJeremy Lin,an Asian-American who garnered mild controversy over his choice of dreadlocks. Former NBA playerKenyon Martinaccused Lin of appropriating African-American culture in a since-deleted social media post, after which Lin pointed out that Martin has multiple Chinese characters tattooed on his body.[184]

David Diamante,the American Bo xingring announcerofItalian Americanheritage, sports prominent dreadlocks.

Hair discrimination

[edit]

On 3 July 2019, California became the first US state to prohibit discrimination over natural hair. GovernorGavin Newsomsigned theCROWN Actinto law, banning employers and schools fromdiscriminating against hairstylessuch as dreadlocks, braids, afros, andtwists.[185]Likewise, later in 2019, Assembly Bill 07797 became law in New York state; it "prohibits racediscrimination based on natural hairor hairstyles ".[186][187]Scholars call discrimination based on hair "hairism". Despite the passage of the CROWN Act, hairism continues, with some Black people being fired from work or not hired because of their dreadlocks.[188][189][190]According to the CROWN 2023 Workplace Research Study, sixty-six percent of Black women change their hairstyle for job interviews, and twenty-five percent of Black women said they were denied a job because of their hairstyle.[191]The CROWN Act was passed to challenge the idea that Black people must emulate other hairstyles to be accepted in public and educational spaces.[192]As of 2023, 24 states have passed the CROWN Act. July 3 is recognized as National CROWN Day, also called Black Hair Independence Day.[193][194][195]

The Perception Institute conducted a "Good Hair Study" using images of Black women wearing natural styles in locs, afros, twists, and other Black hairstyles. The Perception Institute is "a consortium of researchers, advocates and strategists" that uses psychological and emotional test studies to make participants aware of their racial biases. A Black-owned hair supply company,Shea Moisture,partnered with Perception Institute to conduct the study. The tests were done to reduce hair- and racially-based discrimination in education, civil justice, and law enforcement places. The study used animplicit-association teston 4,000 participants of all racial backgrounds and showed most of the participants had negative views about natural Black hairstyles. The study also showedMillennialswere the most accepting of kinky hair texture on Black people. "Noliwe Rooks,aCornell Universityprofessor who writes about the intersection of beauty and race, says for some reason, natural Black hair just frightens some White people. "[196][197]

In September of 2016, a lawsuit was filed by theEqual Employment Opportunity Commissionagainst the company Catastrophe Management Solutions located inMobile, Alabama.The court case ended with the decision that it was not a discriminatory practice for the company to refuse to hire an African American because they wore dreadlocks.[198]

In someTexaspublic schools, dreadlocks are prohibited, especially for male students, because long braided hair is considered unmasculine according to Western standards of masculinity which define masculinity as "short, tidy hair." Black and Native American boys are stereotyped and receive negative treatment and negative labeling for wearing dreadlocks, cornrows, and long braids. Non-white students are prohibited from practicing their traditional hairstyles that are a part of their culture.[199][200]

The policing of Black hairstyles also occurs inLondon, England.Black studentsin England are prohibited from wearing natural hairstyles such as dreadlocks,afros,braids, twists, and other African and Black hairstyles. Black students are suspended from school, are stereotyped, and receive negative treatment from teachers.[201]

InMidrand,north ofJoburginSouth Africa,a Black girl was kicked out of school for wearing her hair in a natural dreadlock style. Hair and dreadlock discrimination is experienced by people of color all over the world who do not conform to Western standards of beauty.[202][203]AtPretoria High School for GirlsinGauteng provincein South Africa, Black girls are discriminated against for wearing African hairstyles and are forced tostraightentheir hair.[204]

In 2017, theUnited States Armylifted the ban on dreadlocks. In the army, Black women can now wearbraidsand locs under the condition that they are groomed, clean, and meet the length requirements.[205]From slavery into the present day, the policing of Black women's hair continues to be controlled by some institutions and people. Even when Black women wear locs and they are clean and well-kept, some people do not consider locs to be feminine and professional because of thenatural kinkytexture of Black hair.[206][207]

Four African countries approved the wearing of dreadlocks in their courts:Kenya,Malawi,South Africa,andZimbabwe.However, hairism continues despite the approval. Although locked hairstyles are a traditional practice on theAfrican continent,some Africans disapprove of the hairstyle because of cultural taboos or pressure from Europeans in African schools and local African governments to conform to Eurocentric standards of beauty.[208][209]

Police profiling

[edit]Black men who wear locs areracially profiledand watched more by the police and are believed to be "thugs" or involved in gangs and violent crimes than Black men who do not wear dreadlocks.[210]

Guinness Book of World Records

[edit]On 10 December 2010, theGuinness Book of World Recordsrested its "longest dreadlocks" category after investigating its first and only female title holder, Asha Mandela, with this official statement:

Following a review of our guidelines for the longest dreadlock, we have taken expert advice and made the decision to rest this category. The reason for this is that it is difficult, and in many cases impossible, to measure the authenticity of the locks due to expert methods employed in the attachment of hair extensions/re-attachment of broken-off dreadlocks. Effectively the dreadlock can become an extension and therefore impossible to adjudicate accurately. It is for this reason Guinness World Records has decided to rest the category and will no longer be monitoring the category for longest dreadlock.[211]

See also

[edit]- List of hairstyles

- Protective hairstyle

- Braids

- Box braids

- Elflock

- Cornrows

- French braid

- Polish plait

References

[edit]- ^"dreadlocks".Oxford English Dictionary.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^"Dreadlocks".Cambridge Dictionary.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^Byrd, Ayana D.; Tharps, Lori L. (2014).Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America.New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 121.ISBN978-1-4668-7210-3.

ByrdTharps2014

- ^Morris, Julia (2014)."Baay Fall Sufi Da'iras Voicing Identity Through Acoustic Communities".African Arts.47(1): 45.doi:10.1162/AFAR_a_00121.JSTOR43306204.S2CID57563314.Retrieved5 December2023.

- ^Botchway (2018)."...The Hairs of Your Head Are All Numbered: Symbolisms of Hair and Dreadlocks in the Boboshanti Order of Rastafari"(PDF).Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 25.Retrieved20 November2023.

- ^Aluko, Adebukola (16 June 2023).""Dada": Beyond The Myths To Smart Haircare ".Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria.Retrieved22 November2023.

- ^Sherrow, Victoria (2023).Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History.Bloomsbury Publishing USA.ISBN9798216171683.

- ^Chikowero, Mhoze (2015).African Music, Power, and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe.Indiana University Press. p. 260.ISBN9780253018090.

- ^"Muila / Mumuila / Mwela / Plain Mumuila / Mountain Mumuila / Mwila".101lasttribes.Retrieved21 December2023.

- ^"Image of Egyptian with locks".freemaninstitute.Retrieved6 October2017.

- ^Egyptian Museum - "Return of the Mummy.Archived2005-12-30 at theWayback MachineToronto Life - 2002."Retrieved 01-26-2007.

- ^Sherrow, Victoria (2023).Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History.Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 140.ISBN9781440873492.

- ^Delongoria (2018)."Misogynoir: Black Hair, Identity Politics, and Multiple Black Realities"(PDF).Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 40.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Dreads.Artisan Books. 1999. p. 22.ISBN9781579651503.

- ^Berdán, Frances F. and Rieff Anawalt, Patricia (1997).The Essential Codex Mendoza.London, England: University of California Press. pp 149.

- ^abPoliakoff, Michael B. (1987).Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture.Yale University Press.p. 172.ISBN9780300063127.

The bo xing boys on a fresco from Thera (now the Greek island of Santorini), also 1500 B.C.E., are less martial with their jewelry and long braids, and it is hard to imagine that they are engaged in a hazardous fight...

- ^abBlencowe, Chris (2013).YRIA: The Guiding Shadow.Sidewalk Editions. p. 36.ISBN9780992676100.

... Archaeologist Christos Doumas, discoverer of Akrotiri, wrote: "Even though the character of the wall-paintings from Thera is Minoan,... the bo xing children with dreadlocks, and ochre-coloured naked fishermen proudly displaying their abundant hauls of blue and yellow fish.

- ^Bloomer, W. Martin (2015).A Companion to Ancient Education.John Wiley & Sons. p. 31.ISBN9781119023890.

Figure 2.1b Two Minoan boys with distinctive hairstyles, bo xing. Fresco from West House, Thera (Santorini), ca. 1600–1500 BCE (now in the National Museum, Athens).

- ^Kerr, Minott."Greek Kouroi".Reed Library.Reed College.Retrieved4 November2023.

- ^Haas; Toppe; Henz (2005)."Hairstyles in the Arts of Greek and Roman Antiquity".Journal of Investigative Dermatology.10(3): 298–300.doi:10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10120.x.PMID16382686.

- ^Stephens, Janet."Know Them by Their Hair".Archeologynow.org.Retrieved8 November2023.

- ^Jenkins, Ian (2001). "Archaic Kouroi in Naucratis: The Case for Cypriot Origin".The American Journal of Archaeology.105(2). American Journal of Archaeology: 168–175.doi:10.2307/507269.ISSN0002-9114.JSTOR507269.

The hair in both is filleted into a series of fine dreadlocks, tucked behind the ears and falling on each shoulder and down the back. A narrow fillet passes around the forehead and disappears behind the ears.... Two are in the British Museum (fig. 17) and another in Boston (fig. 18). These three could have been carved by the same hand. Distinctive points of comparison include the dreadlocks; high, prominent chest without division; sloping shoulders; manner of showing the arms by the side...the torso of a kouros, again in Boston (fig. 19), should probably also be assigned to this group.

- ^Sherrow, Victoria (2023).Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History.Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 140.ISBN9781440873492.

- ^Dreads.Artisan Books. 1999.ISBN9781579651503.

- ^"Tress".Collins Dictionary.Retrieved7 November2023.

- ^Cartwright, Mark."Akrotiri Frescoes".World History Encyclopedia.World History Foundation.Retrieved7 November2023.

- ^"Tress".Dictionary.Retrieved7 November2023.

- ^"Zeitreisen - Vom Einimpfen und Auskampeln".

- ^Sarasohn, Lisa (2021).Getting Under Our Skin: The Cultural and Social History of Vermin.JHU Press.ISBN9781421441382.

- ^Crowder, Nicole (2015)."The roots of fashion and spirituality in Senegal's Islamic brotherhood, the Baye Fall".The Washington Post.Retrieved21 November2023.

- ^Botchway, De-Valera (2018)."...The Hairs of Your Head Are All Numbered: Symbolisms of Hair and Dreadlocks in the Boboshanti Order of Rastafari"(PDF).Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 25 – via jpanafrican.org.

- ^Weston, Mark (24 May 2016)."On the Frontier of Islam: The Maverick Mystics of Senegal".Daily Maverick.Retrieved21 November2023.

- ^Savishinsky (1994)."The Baye Faal of Senegambia: Muslim Rastas in the Promised Land?".Journal of the International African Institute.64(2): 211–219, 212.doi:10.2307/1160980.JSTOR1160980.S2CID145284484.Retrieved21 November2023.

- ^Pellizzi, Francesco (2012).Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 59/60: Spring/Autumn 2011.Harvard University Press. p. 133.ISBN9780873658621.

- ^Loadenthal, Michael (2013)."Jah People: The Cultural Hybridity of White Rastafarians"(PDF).Glocalism.1:12–18.Retrieved9 November2023.

- ^Wakengut, Anastasia (2013)."Rastafari in Germany: Jamaican Roots and Global–Local Influences".Student Anthropologist.3(4): 60–81.doi:10.1002/j.sda2.20130304.0005.

- ^Bronner; Dell Clark (2016).Youth Cultures in America [2 volumes]: [2 volumes].Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 358.ISBN9781440833922.

- ^Grossberg, Lawrence (2005).Cultural Studies: Volume 7.Routledge. p. 408.ISBN9781134863495.

- ^Savishinsky, Neil J. (1994)."Transnational Popular Culture and the Global Spread of the Jamaican Rastafarian Movement".NWIG: New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids.68(3/4): 265–267.JSTOR41849614.Retrieved14 November2023.

- ^Cashmore (2013).Rastaman (Routledge Revivals): The Rastafarian Movement in England.Routledge.ISBN9781135083748.

- ^"19 Celebs Slaying In Beautiful Locs".Essence.Retrieved2020-03-06.

- ^Kuumba, M.; Ajanaku, Femi (1998). "Dreadlocks: The Hair Aesthetics of Cultural Resistance and Collective Identity Formation".Mobilization: An International Quarterly.3(2): 227–243.doi:10.17813/maiq.3.2.nn180v12hu74j318.

- ^"Dread History: The African Diaspora, Ethiopianism, and Rastafari".Smithsonianeducation.org.Smithsonian Institution.Retrieved7 December2023.

- ^Hook, Sue (2010).Hip-Hop Fashion.Capstone. p. 25.ISBN9781429640176.

- ^Allah, Sha Be (11 March 2023)."Exploring Culture: Dreadlocks and Hip Hop".Thesource.Retrieved8 December2023.

- ^Bennett, Dionne; Morgan, Marcyliena (2011)."Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form".Race, Inequality & Culture.2(140): 179–180.JSTOR23047460.Retrieved8 December2023.

- ^Fonseca, Anthony J.; Dawn Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula (2018).Hip Hop around the World [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes].Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 236, 282–283.ISBN9780313357596.

- ^Kemigisha, Martha (May 26, 2023)."Hair goals: 8 male celebrities with gorgeous dreadlocks".Uganda Pulse.Retrieved8 December2023.

- ^C.J., Nelson."How Afrobeats Artists Are Using Fashion to Tell Us Who They Are".Billboard.Retrieved8 December2023.

- ^Mercer, Kobena (2013).Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies.Routledge. pp. 98, 105–109.ISBN9781135204761.

- ^Ntarangwi, Mwenda (2009).East African Hip Hop: Youth Culture and Globalization.University of Illinois Press. pp. 32–33.ISBN9780252076534.

- ^Osumare, H. (2012).The Hiplife in Ghana: West African Indigenization of Hip-Hop.Springer. pp. 90–91, 56, 178.ISBN9781137021656.

- ^Talmor, Ruti (2023).Aesthetic Practices in African Tourism.Taylor & Francis.ISBN9780429534768.

- ^Kauppinen, Anna-Rikka; Spronk, Rachel (2020)."Afro-chic: Beauty, Ethics, and" Locks without Dread ".Green Consumption: The Global Rise of Eco-Chic.pp. 117–122.doi:10.4324/9781003085508-11.ISBN9781000182996.

- ^Brown, Nikki (26 October 2020)."19 Celebs Slaying In Beautiful Locs".Essence.Retrieved15 December2023.

- ^Thompson, Cheryl (2008)."Black Women and Identity: What's Hair Got to Do With It?"(PDF).Michigan Feminist Studies.22(1): 3.Retrieved16 December2023.

- ^Aighewi, Adesuwa (2017)."The fashion industry said my dreadlocks would stop me working. They were wrong".The Guardian.Retrieved19 December2023.

- ^Donato, Al (2015)."Miss Jamaica Is The First Contestant To Wear Dreadlocks to Miss World Pageant".Huffpost.Retrieved16 December2023.

- ^Bremer, Katherine (2007)."Dreadlocked Miss Jamaica puts Rastas in new light".Reuters.Retrieved16 December2023.

- ^"Miss Universe Great Britain".Going-natural.17 July 2018.Retrieved16 December2023.

- ^Steinhoff, Heike (2011).Queer Buccaneers: (de)constructing Boundaries in the Pirates of the Caribbean Film Series Volume 10 of Transnational and Transatlantic American Studies.LIT Verlag Münster. p. 56.ISBN9783643111005.

- ^Shoenberger, Elisa."Documenting the Ephemeral: Burning Man | Archives Deep Dive".Library Journal.Retrieved10 November2023.

- ^Devaney, Jacob (2017)."On Cultural Appropriation And Transformation At Burning Man".Huffington Post.Retrieved10 November2023.

- ^Kozinets; Sherry (2007)."Comedy of the Commons: Nomadic Spirituality and the Burning Man Festival".Consumer Culture Theory (Research in Consumer Behavior.Research in Consumer Behavior.11:119–147.doi:10.1016/S0885-2111(06)11006-6.ISBN978-0-7623-1446-1.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Rosenfeld, Jordana (23 September 2020)."Is spiritual growth possible without confronting whiteness? In 'White Utopias,' cultural appropriation at festivals like Burning Man goes under the microscope".High Country News.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Shujaa, Kenya; Shujaa, Mwalimu J. (2015).The SAGE Encyclopedia of African Cultural Heritage in North America.SAGE Publications. p. 442.ISBN9781483346380.

- ^Wagoner, Mackenzie (21 September 2016)."The Dreadlocks Debate: How Hair Is Sparking the Conversation of the Moment".VOGUE.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^Walker, Kate (19 June 2020)."The Exploited Trendsetter: Who's Really Behind the Looks We Love How popular fashion has appropriated Black culture for years".University Girl Magazine.Retrieved12 December2023.

- ^Donato, Al (2016)."New York Men's Fashion Week Show Casts Only Black Men With Dreadlocks".Huffpost.Retrieved12 December2023.

- ^"Students are claiming the White man harassed over his dreadlocks isn't telling the full story".The Independent.Retrieved2018-07-18.

- ^Ring, Kyle (5 October 2022)."Twisted Locks of Hair: The Complicated History of Dreadlocks".Esquire.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Stephens, Thomas; Rigendinger, Balz (July 29, 2022)."How a white reggae band forced Switzerland to question cultural appropriation".Swiss Broadcasting Corporation SRG SSR. SWI swissinfo.ch.Retrieved1 November2023.

- ^Bolton; Smith; Bebout (2019).Teaching with Tension: Race, Resistance, and Reality in the Classroom.Northwestern University Press.ISBN9780810139114.

- ^"Dear White People: Locs Are Not" Just Hair "".Ebony Magazine.6 April 2016.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^Thompson, MJ (2019)."White Dreadlocks: Black Aesthetics in the Work of Louise Lecavalier and La La La Human Steps".The Body, the Dance and the Text: Essays on Performance and the Margins of History:67–72.ISBN9781476634852.Retrieved7 December2023.

- ^Delongoria (2018)."Misogynoir: Black Hair, Identity Politics, and Multiple Black Realities"(PDF).Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 40.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Kasfir, Sidney (1994)."Reviewed Works: Mammy Water: In Search of the Water Spirits in Nigeria by Sabine Jell-Bahlsen; Mami Wata: Der Geist der Weissen Frau by Tobias Wendl, Daniela Weise".African Arts.27(1): 80.doi:10.2307/3337178.JSTOR3337178.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Opara; Chukwuma (2022).Legacies of Departed African Women Writers: Matrix of Creativity and Power.Rowman & Littlefield. p. 66.ISBN9781666914665.

- ^Dreads.Artisan Books. 1999. p. 22.ISBN9781579651503.

- ^Kasfir, Sidney (1994)."Reviewed Works: Mammy Water: In Search of the Water Spirits in Nigeria by Sabine Jell-Bahlsen; Mami Wata: Der Geist der Weissen Frau by Tobias Wendl, Daniela Weise".African Arts.27(1): 80.doi:10.2307/3337178.JSTOR3337178.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Gardner, Tom (2019)."These Preachers Perform Mass Exorcisms—And Live-Stream Them".The Atlantic.Retrieved12 December2023.

- ^Dreads.Artisan Books. 1999.ISBN9781579651503.

- ^Oyetade, Akintunde (1993)."The Yorùbá Community in London".African Languages and Cultures.6(1): 88.doi:10.1080/09544169308717762.JSTOR1771765.Retrieved5 December2023.

- ^Agwuele, Augustine (2016).The Symbolism and Communicative Contents of Dreadlocks in Yorubaland.Springer. p. 135.ISBN9783319301860.

- ^Idowu, Moses (2009).Moses Orimolade Tunolase: More Than a Prophet.Divine Artillery Publications. p. 46.ISBN9789783570450.

- ^Agwuele, Augustine (2016).The Symbolism and Communicative Contents of Dreadlocks in Yorubaland.Springer. pp. 10, 80–82.ISBN9783319301860.

- ^Abiodun, Hannah; Fashola, Joseph (2021)."The Ontology of Hair and Identity Crises in African Literature"(PDF).IASR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences.1(1): 37.Retrieved11 January2024.

- ^Oche, Gloria (2022)."Dreadlocks: The myths, misconceptions, culture, and lifestyles".News Agency of Nigeria.Retrieved10 November2023.

- ^Gilbert-Hickey; Green-Barteet (2021).Race in Young Adult Speculative Fiction.Univ. Press of Mississippi.ISBN9781496833839.

- ^Agwuele, Augustine (2019)."In Nigeria, dreadlocks are entangled with beliefs about danger and spirituality".The Conservation.Retrieved10 November2023.

- ^Biddle-Perry, Geraldine (2020).A Cultural History of Hair in the Modern Age.Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 32.ISBN9781350122833.

- ^Aluko, Adebukola (16 June 2023).""Dada": Beyond The Myths To Smart Haircare ".Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria.Retrieved22 November2023.

- ^Taylor, Bron; Kaplan, Jeffrey (2005).Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature.Bloomsbury Academic. p. 1035.ISBN9781847062734.

- ^"'People with locs are seen as miscreants'".BBC News.

- ^Agwuele, Augustine (2016).The Symbolism and Communicative Contents of Dreadlocks in Yorubaland.Springer.ISBN9783319301860.

- ^"Black Hairstyles Historical Significance and Etymology"(PDF).Illinois State Board of Education:13.Retrieved22 November2023.

- ^Rhodes, Jerusha (1996)."Fufuo, Dreadlocks, Chickens and Kaya: Practical Manifestations of Traditional Ashanti Religion".African Diaspora.28:18–19.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Cartwright, Angie."The Dreadlocks".Afrostyle Magazine.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Ramalapa, Jedidiah (2021).Soweto to Beirut.African Sun Media. p. 119.ISBN9780620931816.

- ^De Vos, Pierre (4 April 2013)."Putting the 'dread' into 'dreadlocks'".Daily Maverick.Retrieved26 October2023.

- ^Chitando (2004). "Black Female Identities in Harare: The Case of Young Women with Dreadlocks".Zambezia:9–13.S2CID145067627.

- ^Fihlani, Pumza (27 February 2013)."South Africa's dreadlock thieves".BBC News.Retrieved23 December2020.

- ^"Discovering the Vibrant Hamar Tribe: A Glimpse into their Fascinating Culture".Tribes.World.Retrieved28 November2023.

- ^"Muila / Mumuila / Mwela / Plain Mumuila / Mountain Mumuila / Mwila".101lasttribes.Retrieved21 December2023.

- ^"Angola, Mwila Tribe".Atlas of Humanity.Retrieved20 December2023.

- ^Nunoo, Ama (2020)."Meet the Mwila people of Angola whose women cover their hair with cow dung".face2faceafrica.Retrieved21 December2023.

- ^Dapschauskas; Sommer (December 2022). "The Emergence of Habitual Ochre Use in Africa and its Significance for The Development of Ritual Behavior During The Middle Stone Age".Journal of World Prehistory.35(3–4): 233–319.doi:10.1007/s10963-022-09164-1(inactive 2024-07-08).

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2024 (link) - ^McQuail, Lisa (2002).The Masai of Africa.Lerner Publications. p. 39.ISBN9780822548553.

- ^Davies, Monika (2017).Surprising Things We Do for Beauty 6-Pack.Teacher Created Materials. pp. 22–23.ISBN9781493837267.

- ^"The History of Hair".The African American Museum of Iowa.Retrieved24 October2023.

- ^Delongoria, Maria (2018)."Misogynoir: Black Hair, Identity Politics, and Multiple Black Realities"(PDF).Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 40.Retrieved24 October2023.

- ^Byrd, Ayana; Tharps, Lori (2001).Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America.St. Martin Press.ISBN9781250046574.

- ^Byrd, Ayana; Tharps, Lori."Sample text for Hair story: untangling the roots of Black hair in America".Library of Congress.Retrieved1 November2023.

- ^"Colonialism, Hair, and Enslavement".African American Museum of Iowa.Retrieved24 October2023.

- ^Andiswa Tshiki (23 November 2021)."African Hairstyles – The" Dreaded "Colonial Legacy".The Gale Review.Retrieved29 November2023.

- ^Sherrow, Victoria (2023).Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History.Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 140.ISBN9781440873492.

- ^White, Graham; White, Shane (1995)."Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries".The Journal of Southern History.61(1): 53–54.doi:10.2307/2211360.JSTOR2211360.Retrieved14 November2023.

- ^Consentino; Fabius (2001)."Body Talk".African Arts.34(2): 9.JSTOR3337908.Retrieved25 October2023.

- ^Davis-Sivasothy, Audrey (2011).The Science of Black Hair: A Comprehensive Guide to Textured Hair.SAJA Publishing Company. pp. 38, 248.ISBN9780984518425.

- ^Nyela (2021)."Braided Archives: Black hair as a site of diasporic transindividuation".Graduate Thesis Published at York University in Toronto, Ontario:20–24.Retrieved19 November2023.

- ^Jahangir, Rumeana (2015)."How does black hair reflect black history?".BBC News.Retrieved10 November2023.

- ^Owusu, Kwesi (2000).Black British Culture and Society: A Text Reader.Psychology Press. p. 117.ISBN9780415178457.

- ^Connell, Kieran (2019).Black Handsworth: Race in 1980s Britain.University of California Press. p. 105.ISBN9780520971950.

- ^Ajanaku, Femi; Kuumba, M. (1998)."Dreadlocks: The Hair Aesthetics of Cultural Resistance and Collective Identity Formation".Mobilization: An International Quarterly.3(2).Retrieved25 November2023.

- ^Mutukwa, Mendai (2016)."Dreadlocks as a Symbol of Resistance: Performance and Reflexivity".Feminist Africa.21(21): 70–74.JSTOR48725773.Retrieved5 December2023.

- ^Samuels, Anita (1994)."Just Locks".The New York Times.The New York Times.Retrieved16 December2023.

- ^Russell; Russell-Cole; Wilson; Hall (1993).The Color Complex: The Politics of Skin Color Among African Americans.Anchor Books. pp. 82–91.ISBN9780385471619.

- ^Montle (2020)."Debunking Eurocentric ideals of beauty and stereotypes against African natural hair(styles)".Journal of African Foreign Affairs.7(1): 111–127.doi:10.31920/2056-5658/2020/7n1a5.JSTOR26976619.S2CID225984335– via JSTOR.

- ^Erasmus, Zimitri (1997)."'Oe! My Hare Gaan Huistoe': Hair-Styling as Black Cultural Practice ".Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity.32(32): 11–16.doi:10.2307/4066147.JSTOR4066147.Retrieved13 November2023.

- ^Shujaa, Mwalimu J.; Shujaa, Kenya J. (2015).The SAGE Encyclopedia of African Cultural Heritage in North America.Sage Publications. p. 442.ISBN9781483346380.

- ^Brown, Shaunasea (2018).""Don't Touch My Hair": Problematizing Representations of Black Women in Canada "(PDF).Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 69–70.Retrieved14 November2023.

- ^Johnson, Chelsea (18 October 2016)."Kinky, curly hair: a tool of resistance across the African diaspora".USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.Retrieved19 November2023.

- ^Boakye, Omenaa."Everything You Need to Know About Soft Locs: The latest protective style you're already seeing everywhere".InStyle.Retrieved29 November2023.

- ^Ore, Michelle; McKenzie, Janae (13 February 2018)."41 Protective Hairstyles You'll Want to Wear This Summer".Glamour.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^"What Are The Different Types of Dreadlocks?".Style Seat.28 September 2021.Retrieved21 November2023.

- ^Thiga, Tatiana (2023)."Top 20 invisible locs hairstyles to try: Trendy and classy protective hairstyle".yen.gh.Retrieved21 December2023.

- ^Withnell, John G. (1901).The Customs And Traditions Of The Aboriginal Natives Of North Western Australia.ROEBOURNE. p. 14.

- ^Baldwin Spencer and F. J. Gillen (1899).The Native Tribes of North Central Australia.London: Macmillan.

- ^"Aboriginal man with dreadlocks standing next to the expedition's Morris Commercial truck, Warburton Range, western Australia, 1931 / Michael Terry".Trove / Australian Government Library.Retrieved28 October2023.

- ^Grieves, Victoria (2018).""Reggae Became the Main Transporter of Our Struggle... and Our Love"".Transition(126): 43–57.doi:10.2979/transition.126.1.07.S2CID158959786.Retrieved10 November2023.

- ^Gershon, Livia (2023)."Reggae in Australia".Arts and Culture.Retrieved28 October2023.

- ^Ottosson, Ase (2020).Making Aboriginal Men and Music in Central Australia.Routledge.ISBN9781000181784.

- ^Bogin, Benjamin (2008)."The Dreadlocks Treatise: On Tantric Hairstyles in Tibetan Buddhism".History of Religions.48(2): 85–109.doi:10.1086/596567.JSTOR10.1086/596567.S2CID162206598.

- ^Snellgrove, David.The Hevajra Tantra: A Critical Study.vol 1. Oxford University Press. 1959.

- ^Saran, Shyam (2018).Cultural and Civilisational Links between India and Southeast Asia: Historical and Contemporary Dimensions.Springer. p. 265.ISBN9789811073175.

- ^Wedemeyer, Christian (2014).Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions.Columbia University Press. p. 158.ISBN9780231162418.

- ^Bogin, Benjamin (2018)."The Dreadlocks Treatise: On Tantric Hairstyles in Tibetan Buddhism".History of Religions.48(2): 85–95.doi:10.1086/596567.JSTOR10.1086/596567.S2CID162206598.Retrieved26 October2023.

- ^Schmidt-Leukel; Grosshans; Krueger (2021).Ethnic and Religious Diversity in Myanmar: Contested Identities.Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 101.ISBN9781350187412.

- ^Hair: Styling, Culture and Fashion.University of Michigan [Michigan]: Bloomsbury Academic. 2009.ISBN9781845207922.

His jata (dreadlocks) are elegantly styled, and the source of the Ganges issues from his topknot. In the background are the Himalayas where Shiva performs his austerities.

- ^"Why Some Indian Women Are Terrified of Chopping off Their Dreadlocks, Even Though They Can't Move Their Necks".Vice.23 October 2019.Retrieved2021-01-29.

- ^Rattanpal, Divyani (2015-10-06)."Hair and Shanti: What Hair Means to Indians".TheQuint.Retrieved2021-01-29.

- ^"What Sadhus and Sadhvis at Kumbh Told Me About Their Long and Important Dreadlocks".News 18.Retrieved2021-01-29.

- ^"What Sadhus and Sadhvis at Kumbh Told Me About Their Long and Important Dreadlocks".3 February 2019.

- ^Hays, Jeffrey."SADHUS, HINDU HOLY MEN | Facts and Details".factsanddetails.Retrieved2021-01-29.

- ^Lorenzen, David (1972).The Kapalikas and Kalamukhas: Two Lost Saivite Sects.Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. pp. 4, 6, 14, 21–23, 41–42, 47.ISBN0-520-01842-7.

- ^Lorenzen, David (1972).The Kapalikas and Kalamukhas: Two Lost Saivite Sects.Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. pp. 4, 85.ISBN0-520-01842-7.

- ^Trueb, Ralph (2017)."From Hair in India to Hair India".International Journal of Trichology.9(1): 5–6.doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_10_17.PMC5514789.PMID28761257.

- ^Varde, Abhijit (1997).Daughters of Maharashtra: Portraits of Women who are Building Maharashtra: Interviews and Photographs.University of Virginia. p. 12.

- ^Chakraborty, Reshmi (23 October 2019)."Why Some Indian Women Are Terrified of Chopping off Their Dreadlocks, Even Though They Can't Move Their Necks".Vice.Retrieved26 October2023.

- ^Torgaltar, Varsha."This Maharashtra Group is Cutting off Superstition – One Dreadlock at a Time".The Wire.Retrieved27 October2023.

- ^Kassam, Zayn (2017).Women and Asian Religions.Bloomsbury Publishing USA.ISBN9798216166139.

- ^Krueger; Grosshans; Schmidt-Leukel (2021).Ethnic and Religious Diversity in Myanmar: Contested Identities.Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 101.ISBN9781350187412.

- ^Allocco, Amy (2013)."From Survival to Respect: The Narrative Performances and Ritual Authority of a Female Hindu Healer".Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion.29(1): 110.doi:10.2979/jfemistudreli.29.1.101.JSTOR10.2979/jfemistudreli.29.1.101.S2CID145535226.Retrieved5 December2023.

- ^"Dreadlocks".James Madison University.Retrieved22 November2023.

- ^"From slavery to colonialism and school rules: a history of myths about black hair".The Conversation.31 August 2016.Retrieved21 November2023.

- ^McFarlane; Spencer; Samuel Murrell (1998).Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader.Temple University Press. pp. 133–134.ISBN9781566395847.

- ^McFarlane; Spencer; Samuel Murrell (1998).Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader.Temple University Press. pp. 133–134.ISBN9781566395847.

- ^Kimutai, Cyprian (2022)."Why dreadlocks were an important symbol for Kenya's Mau Mau".Pulse.Retrieved30 November2023.

- ^Kinni, Yen-Kini (2015).Pan-Africanism: Political Philosophy and Socio-Economic Anthropology for African Liberation and Governance.African Books Collective. p. 838.ISBN9789956762651.

- ^"Rastafari"(PDF).RE: Online the Place for Excellence:13.Retrieved5 December2023.

- ^Gackstetter Nichols; Kenny (2017).Beauty around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia.Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 93.ISBN9781610699457.

- ^"Dare to dread".The Guardian.2003-08-23.Retrieved2022-11-11.

- ^Samuel Murrell; Spencer; McFarlane (1998).Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader.Temple University Press. p. 32.ISBN9781566395847.

- ^Coertzen; Green (2015).Law and Religion in Africa: The quest for the common good in pluralistic societies.African Sun Media. p. 189.ISBN9781919985633.

- ^Omotoso, Sharon Adetutu (2018)."Editorial: Human Hair: Intrigues and Complications"(PDF).Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 2.Retrieved14 November2023.

- ^"Religions - Rastafari: Bobo Shanti".BBC.co.uk.21 October 2009.Retrieved6 November2019.

- ^Lynch, Annette; Strauss, Mitchell (2014).Ethnic Dress in the United States: A Cultural Encyclopedia.Rowman & Littlefield. p. 248.ISBN9780759121508.

- ^"Rastafarians".Minority Rights.Minority Rights Group International. 19 June 2015.Retrieved26 June2021.

- ^Montlouis, Nathalie (2013).Lords and empresses in and out of Babylon: the EABIC community and the dialectic of female subordination(phd).doi:10.25501/SOAS.00017357.Retrieved6 November2019.

- ^Botchway (2018)."...The Hairs of Your Head Are All Numbered: Symbolisms of Hair and Dreadlocks in the Boboshanti Order of Rastafari"(PDF).Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 21–28.Retrieved20 November2023.

- ^Brown, Nadia; Lemi, Danielle (2021).Sister Style: The Politics of Appearance for Black Women Political Elites.Oxford University Press. p. 18.ISBN9780197540596.

- ^"Matz: NFL players embracing long hair".ESPN.29 December 2010.Retrieved6 October2017.

- ^Morgan, Emmanuel (2022)."For Dreadlocked N.F.L. Players, Hair Is a Point of Pride".The New York Times.The New York Times.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^"Jeremy Lin's dreadlocks have led to all kinds of comments — even Lil B's support".6 October 2017.

- ^"California bans racial discrimination based on hair in schools and workplaces".JURIST.Retrieved2019-07-03.

- ^"New York bans discrimination against natural hair".The Hill.2019-07-13.Retrieved2019-07-18.

- ^Lee; Nambudiri (2021)."The CROWN act and dermatology: Taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination".Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.84(4): 1181–1182.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065.PMID33290804.S2CID228078854.Retrieved27 October2023.

- ^Donahoo (2021)."Why We Need a National CROWN Act".The Body Politic: Women's Bodies and Political Conflict.10(2).Retrieved27 October2023.

- ^Alcindor, Yamiche; Wellford, Rachael (2021)."How hair discrimination impacts Black Americans in their personal lives and the workplace".PBS News Hour.Retrieved13 November2023.

- ^"Strands of Inspiration: Exploring Black Identities through Hair".National Museum of African American History and Culture.Smithsonian Institution.Retrieved19 November2023.

- ^Christ, Ginger."Two-thirds of Black women change their hair for job interviews, even as CROWN Act support grows".HRdive.Retrieved16 December2023.

- ^Donahoo, Sarah; Smith, Asia (2022)."Controlling the Crown: Legal Efforts to Professionalize Black Hair".Race and Justice.12(1): 182–203.doi:10.1177/2153368719888264.S2CID214303469.Retrieved20 November2023.

- ^Payne-Patterson, Jasmine."The CROWN Act: A jewel for combating racial discrimination in the workplace and classroom".Economic Policy Institute.Retrieved28 November2023.

- ^Hays, Gabrielle (July 3, 2023)."When CROWN acts stall in states, cities step in to ban hair discrimination".PBS. PBS News Hour.Retrieved28 November2023.

- ^Hardaway, Brittany (July 3, 2023)."National CROWN Day celebrates Black hair independence".13 WREX News.Retrieved28 November2023.

- ^Bates, Kare."New Evidence Shows There's Still Bias Against Black Natural Hair".NPR.Retrieved21 November2023.

- ^Martin, Areva (2017)."The Hatred of Black Hair Goes Beyond Ignorance".Times Magazine.Retrieved21 November2023.

- ^Gutierrez-Morfin, Noel (2016)."U.S. Court Rules Dreadlock Ban During Hiring Process Is Legal A U.S. Court of Appeals has ruled that denying potential Black employees for wearing dreadlocks does not legally constitute discrimination".NBC News.Retrieved9 November2023.

- ^Banks, Patricia (2023)."No Dreadlocks Allowed: Race, Hairstyles, and Exclusion in Schools".Multicultural Perspectives.25(1): 30–38.doi:10.1080/15210960.2022.2162525.S2CID258313128.Retrieved27 October2023.

- ^Serrano, Alejandro (March 21, 2023)."Texas lawmaker again tries to block discriminatory hairstyle bans in schools and workplaces".The Texas Tribune.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Joseph-Salisbury; Connelly (2018)."'If Your Hair Is Relaxed, White People Are Relaxed. If Your Hair Is Nappy, They're Not Happy': Black Hair as a Site of 'Post-Racial' Social Control in English Schools ".Social Sciences.7(11): 219.doi:10.3390/socsci7110219.

- ^Magadla, Mahlogonolo; Sibiya, Noxolo (August 16, 2023)."Girl kicked out of school for her natural dreadlocks".Sowetan Live News.Retrieved28 October2023.

- ^Chappell, Kate (July 31, 2020)."Jamaica's high court rules school can ban dreadlocks".Washington Post.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Jackson, Jada (2 November 2021)."Some South African Schools Still Have" Blatantly Racist "Dress Codes".Allure.Retrieved29 November2023.

- ^Mele, Christopher (2017)."Army Lifts Ban on Dreadlocks, and Black Servicewomen Rejoice".The New York Times.New York Times.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^Smith (2018)."The Policing of Black Women's Hair in the Military"(PDF).Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies.12(8): 51–55.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^Bero, Tayo."Tangled Roots: Decoding the History of Black Hair".CBC.Radio Canada.Retrieved19 November2023.

- ^Ntreh, Hii (March 26, 2021)."Four African countries where dreadlocks have been approved by courts".Face2Face Africa.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Princewill, Nimi (May 22, 2023)."Their son was banned from school for 3 years because of his dreadlocks".CNN World.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^McWhorter, John (14 September 2011)."Driving While Dreadlocked: Why Police Are So Bad At Racial Profiling".The New Republic.Retrieved18 November2023.

- ^"Longest Dreadlock Record – Rested".Archived fromthe originalon 2011-10-05.

External links

[edit] Media related toDreadlocksat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toDreadlocksat Wikimedia Commons- Celtic Hair Historyfrom Haverford University student blogs

- The cultural ramifications of dreadlocksfrom theWashington Post

- Dreadlocks Story– Documentary by Linda Aïnouche

- Guardianarticle