EC Comics

This article needs to beupdated.(February 2024) |

| |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Publishing |

| Genre | |

| Founded | 1944 |

| Founder | Max Gaines |

| Defunct | 1956[a] |

| Headquarters | New York City, New York ,U.S. |

Key people | Max Gaines William Gaines |

| Products | Comics |

| Owner | Gaines family[1] |

E.C. Publications, Inc.,(doing business asEC Comics) is anAmerican comic bookpublisherspecialized inhorror fiction,crime fiction,satire,military fiction,dark fantasy,andscience fictionfrom the 1940s through the mid-1950s, notably theTales from the Cryptseries. Initially, EC was founded asEducational ComicsbyMaxwell Gainesand specialized in educational and child-oriented stories. After Max Gaines died in a boating accident in 1947, his sonWilliam Gainestook over the company and was renamedEntertaining Comics.He printed more mature stories, delving into horror, war, fantasy, science-fiction, adventure, and other genres. Noted for their high quality and shock endings,[2]these stories were also unique in their socially conscious, progressive themes (includingracial equality,anti-war advocacy,nuclear disarmament,andenvironmentalism) that anticipated theCivil Rights Movementand the dawn of the1960s counterculture.[3]In 1954–55, censorship pressures prompted it to concentrate on the humor magazineMad,leading to the company's greatest and most enduring success. Consequently, by 1956, the company ceased publishing all its comic lines exceptMad.

History

[edit]1944–1950: Founding of publisher as Educational Comics

[edit]

The firm, first known as Educational Comics, was founded byMax Gaines,former editor of the comic-book companyAll-American Publications,and it was initially a shell company of All-American. When that company merged withDC Comicsin June 1945,[4]Gaines retained rights to the comic bookPicture Stories from the Bible,and began his new company using the EC name with a plan to market comics about science, history, and theBibleto schools and churches, and soon expanded to produce children's humor titles.[5]A decade earlier, Max Gaines had been one of the pioneers of the comic book form, withEastern Color Printing's proto-comic bookFunnies on Parade,and withDell Publishing'sFamous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics,considered by historians the first trueAmerican comic book.[6]

1950–1955: Rebranded as Entertaining Comics, introduction to "New Trend"

[edit]When Max Gaines died in 1947 in a boating accident, his sonWilliaminherited the comics company. After four years (1942–1946) in theArmy Air Corps,Gaines had returned home to finish school atNew York University,planning to work as a chemistry teacher. He never taught but instead took over the family business. In 1949 and 1950, Bill Gaines began a line of new titles featuringhorror,suspense,science fiction,military fictionandcrime fiction.His editors,Al FeldsteinandHarvey Kurtzman,who also drew covers and stories, gave assignments to such prominent and highly accomplished freelance artists asJohnny Craig,Reed Crandall,Jack Davis,Will Elder,George Evans,Frank Frazetta,Graham Ingels,Jack Kamen,Bernard Krigstein,Joe Orlando,John Severin,Al Williamson,Basil Wolverton,andWally Wood.With input from Gaines, the stories were written by Kurtzman, Feldstein, and Craig. Other writers, includingCarl Wessler,Jack Oleck,andOtto Binder,were later brought on board.

EC succeeded with its fresh approach and pioneered forming relationships with its readers through its letters to the editor and fan organization, the National EC Fan-Addict Club. EC Comics promoted its stable of illustrators, allowing each to sign his art and encouraging them to develop distinctive styles; the company published one-page biographies of them in comic books. This was in contrast to the industry's common practice, in which credits were often missing, although some artists at other companies, such as theJack Kirby–Joe Simonteam,Jack ColeandBob Kanehad been prominently promoted.

EC published distinct lines of titles under its Entertaining Comics umbrella. Most notorious were its horror books,Tales from the Crypt,The Vault of Horror,andThe Haunt of Fear.These titles reveled in a gruesomejoie de vivre,with grimly ironic fates meted out to many of the stories' protagonists. The company's war comics,Frontline CombatandTwo-Fisted Tales,often featured weary-eyed, unheroic stories out of step with the jingoistic times.Shock SuspenStoriestackled weighty political and social issues such asracism,sex,drug use,and the American way of life. EC always claimed to be "proudest of our science fiction titles", withWeird ScienceandWeird Fantasypublishing stories unlike thespace operafound in such titles asFiction House'sPlanet Comics.Crime SuspenStorieshad many parallels withfilm noir.As noted byMax Allan Collinsin his story annotations forRuss Cochran's 1983 hardcover reprint ofCrime SuspenStories,Johnny Craig had developed a "film noir-ish bag of effects "in his visuals,[page needed]while characters and themes found in the crime stories often showed the strong influence of writers associated withfilm noir,notablyJames M. Cain.[citation needed]Craig excelled in drawing stories of domestic scheming and conflict, leadingDavid Hajduto observe:

To young people of the postwar years, when the mainstream culture glorified suburban domesticity as the modern American ideal – the life that made theCold Warworth fighting – nothing else in the panels of EC comics, not the giant alien cockroach that ate earthlings, not the baseball game played with human body parts, was so subversive as the idea that the exits of theLong Island Expresswayemptied onto levels of Hell.[7]

Superior illustrations of stories with surprise endings became EC's trademark. Gaines would generally stay up late and read large amounts of material while seeking "springboards" for story concepts. The next day he would present each premise until Feldstein found one that he thought he could develop into a story.[8]At EC's peak, Feldstein edited seven titles while Kurtzman handled three. Artists were assigned stories specific to their styles; for example, Davis and Ingels often drew gruesome, supernatural-themed stories, while Kamen and Evans did tamer material.[9]

With hundreds of stories written, common themes surfaced. Some of EC's more well-known themes include:

- An ordinary situation given an ironic and gruesome twist, often aspoetic justicefor a character's crimes. In "Collection Completed", a man takes uptaxidermyto annoy his wife. When he kills and stuffs her beloved cat, the wife snaps and kills him, stuffing and mounting his body. In "Revulsion", a spaceship pilot is bothered by insects due to an experience when he found one in his food. After the story, a giantalieninsect screams in horror at finding the dead pilot in his salad.Dissection,the boiling oflobsters,Mexican jumping beans,fur coats,andfishingare just a small sample of the kind of situations and objects used in this fashion.

- The "Grim Fairy Tale", featuring gruesome interpretations of suchfairy talesas "Hansel and Gretel","Sleeping Beauty",and"Little Red Riding Hood".[10]

- Siamese twinswere a popular theme, primarily in EC's three horror comics. No fewer than nine Siamese twin stories appeared in EC's horror and crime comics from 1950 to 1954. In an interview, Feldstein speculated that he and Gaines wrote so many Siamese twin stories because of the interdependence they had on each other.[11]

- Adaptations ofRay Bradburyscience-fiction stories appeared in two dozen EC comics starting in 1952. It began inauspiciously, with an incident in which Feldstein and Gainesplagiarizedtwo of Bradbury's stories and combined them into a single tale. Learning of the story, Bradbury sent a note praising them, while remarking that he had "inadvertently" not yet received his payment for their use. EC sent a check and negotiated a productive series of Bradbury adaptations.[12]

- Stories with a political message, which became common in EC's science fiction and suspense comics. Among the many topics werelynching,antisemitism,andpolice corruption.[13]

The three horror titles featured stories introduced by a trio ofhorror hosts:The Crypt KeeperintroducedTales from the Crypt;The Vault-Keeperwelcomed readers toThe Vault of Horror;and theOld Witchcackled overThe Haunt of Fear.Besides gleefully recounting the unpleasant details of the stories, the characters squabbled with one another, unleashed an arsenal of puns, and even insulted and taunted the readers: "Greetings, boils and ghouls..." This irreverent mockery of the audience also became the trademark attitude ofMad,and such glib give-and-take was later mimicked by many, includingStan LeeatMarvel Comics.[citation needed]

EC's most enduring legacy came withMad,which started as a side project for Kurtzman before buoying the company's fortunes and becoming one of the country's most notable and long-running humor publications. When satire became an industry rage in 1954, and other publishers created imitations ofMad,EC introduced a sister title,Panic,edited by Al Feldstein and using the regularMadartists plusJoe Orlando.[citation needed]

1955–1956: "New Direction" and "Picto-Fiction"

[edit]EC shifted its focus to a line of more realistic comic book titles, includingM.D.andPsychoanalysis(known as theNew Directionline). It also renamed its remaining science-fiction comic. Since the initial issues did not carry the Comics Code seal, the wholesalers refused to carry them. After consulting with his staff, Gaines reluctantly started submitting his comics to the Comics Code; all the New Direction titles carried the seal starting with the second issue. This attempted revamp failed commercially and after the fifth issue, all the New Direction titles were canceled.[14]Incredible Science Fiction#33 was the last EC comic book published.[15]

Gaines switched focus to EC's Picto-Fiction titles, a line of typeset black-and-white magazines with heavily illustrated stories. Fiction was formatted to alternate illustrations with blocks of typeset text, and some of the contents were rewrites of stories previously published in EC's comic books. This experimental line lost money from the start and only lasted two issues per title. When EC's national distributor went bankrupt, Gaines dropped all of his titles exceptMad.[16]

1960–1989: Acquisition from Kinney National Company, focus towardsMADand other licensing

[edit]Madsold well throughout the company's troubles, and Gaines focused exclusively on publishing it in magazine form. This move was to reconcile its editorHarvey Kurtzman,who had received an offer to join the magazinePageant,[17]but preferred to remain in charge of his magazine. The switch also removedMadfrom the auspices of theComics Code.Kurtzman, regardless, leftMadsoon afterward when Gaines would not give him 51 percent control of the magazine, and Gaines brought backAl Feldsteinas Kurtzman's successor. The magazine enjoyed great success for decades afterward.[18]

Gaines sold the company in the 1960s as E.C. Publications, Inc., and was eventually absorbed into the same corporation that later purchasedNational Periodical Publications(later known asDC Comics).

During the 1960s, Gaines granted Bob Barrett, Roger Hill, and Jerry Norton Weist (1949–2011), the co-founder ofMillion Year Picnic,permission to produce aEC Comicsfanzine "Squa Tront" (1967 - 1983) that would last for several years.[19][20]In June 1967,Kinney National Company(it formed on August 12, 1966, after Kinney Parking/National Cleaning merge) bought National Periodical and E.C., then it purchasedWarner Bros.-Seven Artsin early 1969. Due to a financial scandal involving price fi xing in its parking operations, Kinney Services spun off its non-entertainment assets asNational Kinney Corporationin September 1971, and it changed names toWarner Communicationson February 10, 1972.[21]

TheTales from the Crypttitle was licensed for amovie of that namein 1972. This was followed by another film,The Vault of Horror,in 1973. The omnibus moviesCreepshow(1982) andCreepshow 2,while using original scripts written byStephen KingandGeorge A. Romero,were inspired by EC's horror comics.[citation needed]Creepshow 2included animated interstitial material between vignettes, featuring a young protagonist who goes to great length to acquire and keep possession of an issue of the comic bookCreepshow.[citation needed]

In 1989,Tales from the Cryptbegan airing on the U.S.cable-TV networkHBO.The series ran through 1996, comprising 93 episodes and seven seasons.Tales from the Cryptspawned twochildren's television seriesonbroadcast TV,Tales from the CryptkeeperandSecrets of the Cryptkeeper's Haunted House.It also spawned three "Tales from the Crypt" -branded movies,Demon Knight,Bordello of Blood,andRitual.In 1997, HBO followed the TV series with the similarPerversions of Science(comprising 10 episodes), the episodes of which were based on stories from EC'sWeird Science.[citation needed]

1973–2024: Focus on reprints

[edit]Although the last non-MadEC publication came out in 1956, EC Comics have remained popular for half a century, due to reprints that have kept them in the public eye. In 1964–1966,Ballantine Bookspublished five black-and-white paperbacks of EC stories:Tales of the Incredibleshowcased EC science fiction, while the paperbacksTales from the CryptandThe Vault of Horrorreprinted EC horror tales. EC's Ray Bradbury adaptations were collected inThe Autumn People(horror and crime) andTomorrow Midnight(science fiction).[22]

The EC Horror Library(Nostalgia Press, 1971) featured 23 EC stories selected byBhob Stewartand Bill Gaines, with an introduction by Stewart and an essay by theater criticLarry Stark.One of the first books to reprint comic book stories in color throughout, it followed the original color guides byMarie Severin.In addition to the stories from EC's horror titles, the book also includedBernard Krigstein's famous "Master Race" story fromImpactand the first publication ofAngelo Torres' "An Eye for an Eye", originally slated for the final issue ofIncredible Science Fictionbut rejected by the Comics Code.[23]

East Coast Comix reprinted several of EC's New Trend comics in comic form between 1973 and 1975. The first reprint was the final issue ofTales from the Crypt,with the title revised to stateThe Crypt of Terror.This issue was originally meant to be the first issue of a fourth horror comic which was changed to the final issue ofTales from the Cryptat the last minute when the horror comics were cancelled in 1954. A dozen issues ended up being reprinted.[24]

Russ Cochranreprints includeEC Portfolios,The Complete EC Library,EC Classics,RCP Reprints(Russ Cochran),EC Annuals,andEC Archives(hardcover books). The EC full-color hardcovers were under the Gemstone imprint. Dark Horse continued this series in the same format.[citation needed]

In February 2010,IDW Publishingbegan publishing a series of Artist's Editions books in 15 "× 22" format, which consist of scans of the original inked comic book art, including pasted lettering and other editorial artifacts that remain on the original pages.[25][26]Subsequent EC books in the series included a collection ofWally Wood's EC comic stories,[27]a collection of stories fromMad,[25]and books collecting the work ofJack Davis[28]andGraham Ingels.[29]

In 2012,Fantagraphics Booksbegan a reprint series calledThe EC Artists' Libraryfeaturing the comics published by EC, releasing each book by artist. This collection is printed inblack and white.[30]

In 2013,Dark Horse Comicsbegan reprinting theEC Archivesin hardcover volumes, picking up where Gemstone left off, and using the same hardcover full-color format. The first volume to be reprinted wasTales From the Crypt:Volume 4,with an essay by Cochran.[31]

2024–present: Return to comics

[edit]In February 2024,Oni Pressannounced that it will revive the brand,[32]starting with horror titleEpitaphs from the Abyssand the science fiction titleCruel Universe.[33]

The Gaines family licenses the titles.[34]

Criticisms and controversies

[edit]Beginning in the late 1940s, the comic book industry became the target of mounting public criticism for the content of comic books and their potentially harmful effects on children. The problem came to a head in 1948 with the publication by Dr.Fredric Werthamof two articles: "Horror in the Nursery" (inCollier's) and "The Psychopathology of Comic Books" (in theAmerican Journal of Psychotherapy). As a result, anindustry trade group,theAssociation of Comics Magazine Publishers,was formed in 1948 but proved ineffective. EC left the association in 1950 after Gaines argued with its executive director, Henry Schultz. By 1954 only three comic publishers were still members, and Schultz admitted that the ACMP seals placed on comics were meaningless.[35]

In 1954, the publication of Wertham'sSeduction of the Innocentand a highly publicized Congressional hearing onjuvenile delinquencycast comic books in an especially poor light. At the same time, a federal investigation led to a shakeup in the distribution companies that delivered comic books andpulp magazinesacross America. Sales plummeted, and several companies went out of business.[citation needed]

Gaines called a meeting of his fellow publishers and suggested that the comic book industry gather to fight outside censorship and help repair the industry's damaged reputation. They formed theComics Magazine Association of Americaand itsComics Code Authority.The CCA code expanded on the ACMP's restrictions. Unlike its predecessor, the CCA code was rigorously enforced, with all comics requiring code approval before their publication. This not being what Gaines intended, he refused to join the association.[36]Among the Code's new rules were that no comic book title could use the words "horror" or "terror" or "weird" on its cover. When distributors refused to handle many of his comics, Gaines ended publication of his three horror and the twoSuspenStorytitles on September 14, 1954.

"Judgment Day"

[edit]

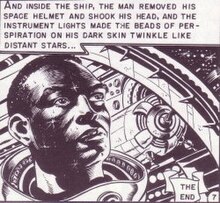

Gaines waged several battles with the Comics Code Authority to keep his magazines free from censorship. In one particular example noted by comics historian Digby Diehl, Gaines threatened Judge Charles Murphy, the Comics Code Administrator, with a lawsuit when Murphy ordered EC to alter the science-fiction story "Judgment Day", inIncredible Science Fiction#33 (February 1956).[37]The story, by the writerAl Feldsteinand artistJoe Orlando,was a reprint from the pre-CodeWeird Fantasy#18 (April 1953), inserted when the Code Authority had rejected an initial, original story, "An Eye for an Eye", drawn by Angelo Torres, but was itself also "objected to" because of "the central character beingBlack".[38]

The story depicted a human astronaut, a representative of the Galactic Republic, visiting the planet Cybrinia, inhabited by robots. He finds the robots divided into functionally identical orange and blue races, with one having fewer rights and privileges than the other. The astronaut determines that due to the robots' bigotry, the Galactic Republic should not admit the planet until these problems are resolved. In the final panel, he removes his helmet, revealing he is a Black man.[37]Murphy demanded, without any authority in the Code, that the Black astronaut had to be removed.[citation needed]

As Diehl recounted inTales from the Crypt: The Official Archives:

This really made 'em go bananas in the Code czar's office. "Judge Murphy was off his nut. He was really out to get us", recalls [EC editor] Feldstein. "I went in there with this story and Murphy says, 'It can't be a Black man'. But... but that's the whole point of the story!" Feldstein sputtered. When Murphy continued to insist that the Black man had to go, Feldstein put it on the line. "Listen", he told Murphy, "you've been riding us and making it impossible to put out anything at all because you guys just want us out of business". [Feldstein] reported the results of his audience with the czar to Gaines, who was furious [and] immediately picked up the phone and called Murphy. "This is ridiculous!" he bellowed. "I'm going to call a press conference on this. You have no grounds, no basis, to do this. I'll sue you". Murphy made what he surely thought was a gracious concession. "All right. Just take off the beads of sweat". At that, Gaines and Feldstein both went ballistic. "Fuck you!" they shouted into the telephone in unison. Murphy hung up on them, but the story ran in its original form.[15]

Feldstein, interviewed for the bookTales of Terror: The EC Companion,reiterated his recollection of Murphy making the request:

So he said it can't be a Black [person]. So I said, "For God's sakes, Judge Murphy, that's the whole point of the Goddamn story!" So he said, "No, it can't be a Black". Bill [Gaines] just called him up [later] and raised the roof, and finally they said, "Well, you gotta take the perspiration off". I had the stars glistening in the perspiration on his Black skin. Bill said, "Fuck you", and he hung up.[39]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^"E.C. Publications, Inc."continues to publishMad.

References

[edit]Citation

[edit]- ^Komassa, Cody."Tales from EC Comics: Behind the Bend".Bend Goods.Archived fromthe originalon September 15, 2017.RetrievedMay 26,2017.

- ^Groth, Gary (January 23, 2013)."Entertaining Comics".The Comics Journal.RetrievedDecember 7,2018.

- ^Duin, Steve (April 30, 2016)."The enduring art of EC Comics".Oregon Live.RetrievedDecember 7,2018.

- ^Schelly 2008.

- ^Booker 2014.

- ^Goulart 2004.

- ^Hajdu 2008,p. 180.

- ^Diehl 1996,p. 30–32.

- ^Diehl 1996,pp. 48–49.

- ^Diehl 1996,p. 51.

- ^Diehl 1996,p. 50.

- ^Gaines & Feldstein 1980.

- ^Diehl 1996,pp. 37, 40.

- ^Diehl 1996,p. 94.

- ^abDiehl 1996,p. 95.

- ^Diehl 1996,pp. 148–49.

- ^Diehl 1996,p. 147.

- ^Diehl 1996,p. 150.

- ^Jerry Weist (1949-2011). Obituary. January 13, 2011.https://locusmag /2011/01/jerry-weist-1949-2011/

- ^Hill, Roger. In Memoriam: Jerry Weist. 2011.https://scoop.previewsworld /Home/4/1/73/1012?articleID=104708

- ^Bruck 2013.

- ^Von Bernewitz & Geissman 2000,p. 208.

- ^Von Bernewitz & Geissman 2000,p. 209.

- ^Von Bernewitz & Geissman 2000,p. 211.

- ^abDoctorow, Cory(March 22, 2013)."MAD Artist's Edition: a massive tribute to Harvey Kurtzman".Boing Boing.RetrievedMay 20,2019.

- ^Rogers, Sean (July 19, 2011)."I Thought It Was Worth Doing, and That Was Enough: The Walter Simonson Interview".The Comics Journal.RetrievedMay 20,2019.

- ^Nadel, Dan (March 26, 2012)."A Few Notes on Wally Wood's EC Stories Artist's Edition"".The Comics Journal.Archived fromthe originalon January 18, 2022.RetrievedMay 20,2019.

- ^"Jack Davis: EC Stories – Artist's Edition".ComicBookRealm.RetrievedMay 20,2019.

- ^Johnston, Rich (March 13, 2013)."How The Artist's Editions Won Comics – Wondercon".Bleeding Cool.

- ^"The EC Comics Library".Fantagraphics Books.Archived fromthe originalon March 1, 2016.RetrievedSeptember 5,2017.

- ^Jennings, Dana (October 24, 2013)."They're... They're Still Alive!".The New York Times.RetrievedJanuary 3,2018.

- ^Kit, Borys (February 19, 2024)."After 70 Years, EC Comics Returns from the Crypt in Oni Press Deal".The Hollywood Reporter.RetrievedFebruary 21,2024.

- ^Johnston, Rich(February 19, 2024)."More Creators Oni Press EC Comics Revival Include Brian Azzarello".Bleeding Cool.RetrievedFebruary 22,2024.

- ^Gustines, George Gene (February 19, 2024)."It's Alive! EC Comics Returns".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.RetrievedFebruary 22,2024.

- ^Diehl 1996,p. 83.

- ^Von Bernewitz & Geissman 2000,p. 94.

- ^abLundin, Leigh (October 16, 2011)."The Mystery of Superheroes".Orlando:SleuthSayers.org.

- ^Thompson, Don & Maggie,"Crack in the Code",Newfangles#44, February 1971.

- ^Von Bernewitz & Geissman 2000,p. 88.

Sources

[edit]- Schelly, Bill(2008).Man of Rock: A Biography of Joe Kubert.Fantagraphics Books.ISBN978-1-56097-928-9.

- Goulart, Ron (2004).Comic Book Encyclopedia.New York:Harper Entertainment.ISBN978-0-06053-816-3.

- Hajdu, David (2008).The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How It Changed America.Farrar, Straus & Giroux.ISBN978-1-42993-705-4.

- Gaines, Bill; Feldstein, Al (1980).The Complete EC Library: Weird Fantasy Volume 3.Russ Cochran.ISBN978-1-5067-0501-9.

- Diehl, Digby (1996).Tales from the Crypt: The Official Archives.New York: St. Martin's Press.ISBN978-0-312-14486-9.

- Bruck, Connie(2013).Master of the Game: Steve Ross and the Creation of Time Warner.New York: Simon and Schuster.ISBN978-1-4767-3770-6.RetrievedAugust 30,2015.

- Von Bernewitz, Fred; Geissman, Grant (2000).Tales of Terror: The EC Companion.Timonium, Maryland,andSeattle, Washington:Gemstone PublishingandFantagraphics Books.ISBN978-1-56097-403-1.

- Booker, M. Keith (2014).Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas.ABC-Clio.ISBN978-0-313-39751-6.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- "Senate Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency Interim Report of the Committee on the Judiciary".US Congress.Senate.Committee on the Judiciary. Juvenile Deliquency. 1955–6. (Via ReoCities).LCCN55060638.Archived fromthe originalon October 27, 2009..

- Harris, Franklin (June 2005)."The Long, Gory Life of EC Comics".Reason.Archivedfrom the original on July 22, 2010.

- "Weird Fantasy".(fan site reprinting Russ Cochran Newsletter.Archivedfrom the original on July 18, 2011.