Early modern Romania

| History ofRomania |

|---|

|

|

|

Theearly modern times in Romaniastarted after the death ofMichael the Brave,[1]who ruled in apersonal union,Wallachia,Transylvania,andMoldavia– three principalities in the lands that now formRomania– for three months, in 1600. The three principalities were subjected to theOttoman Empire,and paid a yearly tribute to theOttoman Sultans,but they preserved their internal autonomy. In contrast,Dobrujaand theBanatwere fully incorporated into the Ottoman Empire.

TheEastern Orthodoxprinces of Wallachia and Moldavia ruled their realms with absolute power, but the boyars took control of state administration in the 1660s and 1670s. The growing influence of Greeks (who administered state revenues and seized landed estates) caused bitter conflicts in both principalities. Due to extensive taxation, the peasants often rebelled against their lords. The long reign ofMatei Basarabin Wallachia and ofVasile Lupuin Moldavia contributed to the development of local economy (especially mining and commerce). Most princes of Wallachia and Moldavia also paid tribute to theprinces of Transylvania.[citation needed]The latter administered their realm in cooperation with the Diet, composed of the representatives of theHungarian noblemen,theTransylvanian Saxons,and theSzékelysand of delegates appointed by the monarchs. In the principality, Catholicism,Lutheranism,Calvinism,andUnitarianismenjoyed an official status. Romanians had no representatives in the Diet and their Eastern Orthodox religion was only tolerated. The three outstanding princes – the CalvinistStephen Bocskai,Gabriel Bethlen,andGeorge I Rákóczi– expanded their countries and defended the liberties of the Estates inRoyal Hungaryagainst the Habsburgs in the first half of the 17th century.

During this period the lands inhabited by Romanians were characterised by the slow disappearance of thefeudalsystem,[dubious–discuss]by the leadership of some rulers likeDimitrie CantemirinMoldavia,Constantin BrâncoveanuinWallachia,Gabriel BethleninTransylvania,thePhanariot Epoch,and the appearance of theRussian Empireas a political and military influence.

Background[edit]

Thelands that now form Romaniawere divided among various polities in the Middle Ages.[2]Banat,Crişana,MaramureşandTransylvaniawere integrated into theKingdom of Hungary.[3][4]WallachiaandMoldaviadeveloped into independent principalities in the 14th century.[5]Dobrujaemerged asan autonomous realmafter the disintegration ofBulgariain the 1340s.[6]

In accordance with the Byzantine political traditions, the princes of Wallachia and Moldavia wereautocratswho ruled with absolute power.[7]Any male member of the royal families could be elected prince, which caused internal strives, giving pretext to the neighboring powers for intervention.[8]Most princes of Wallachia accepted the suzerainty of thekings of Hungary;the Moldavian monarchs preferred to yield to thekings of Poland.[9][10]Royal councils – which consisted of thelogofăt,thevornic,and other high officials – assisted the monarchs, but the princes could also discuss the most important matters at the assembly of the Orthodox clergy, theboyarsand the army.[11][12][13]The Orthodox Church, especially the monasteries, held extensive domains in both principalities.[14]The boyars were landowners who enjoyed administrative and judicial immunities.[15]A group of free peasants (known asrăzeşiin Wallachia andmoşneniin Moldavia) existed in each principality, but the princes' most subjects wereserfs– therumâniin Wallachia, and theveciniin Moldavia – who paidtithesor provided specific services to their lords.[15][16]Gypsyslavesalso played an eminent role in the economy, especially as black-smiths, basket-makers, and goldwashers.[17] The Kingdom of Hungary were divided intocounties.[3]Theheadsof most counties were directly subordinated to the sovereign, with the exception of the seven Transylvanian counties which were under the authority of a higher royal official, thevoivode.[3]Assemblies ofnoblemenwere the most important administrative bodies in the counties; in Transylvania, the voivodes held joint assemblies.[18]In theory, all noblemen enjoyed the same privileges, for instance, they were exempted of taxes.[19]However, the so-calledconditional nobles– including the Romaniancneazesand thenobles of the Church– did not have the same liberties: they paid taxes or rendered specific services either to the monarch or to their lords.[20]TheTransylvanian Saxons,whose territories were divided intoseats,formed an autonomous community which remained independent of the authority of the voivodes.[21]TheHungarian-speakingSzékelys,who lived in the easternmost part of Transylvania, were also organized into seats.[21]On 16 September 1437 the Transylvanian noblemen and the heads of the Saxon and Székely communities concluded an alliance – theUnion of the Three Nations– against the Hungarian and Romanian peasants who had risen up inopen rebellion.[22][23]This Union developed into the constitutional framework of the administration of Transylvania in the next decades.[24]Within the peasantry, Romanians had a special position, for instance, they did not pay the ecclesiastic tithe, payable by all Catholic peasants.[25]

The expansion of theOttoman Empirereached the Danube around 1390.[26]The Ottomans invaded Wallachia in 1390 and occupied Dobruja in 1395.[27][28]Wallachia paid tribute to the Ottomans for the first time in 1417, Moldavia in 1456.[29]However, the two principalities were not annexed, their princes were only required to assist the Ottomans in their military campaigns.[30]The most outstanding 15th-century Romanian monarchs –Vlad the Impaler of WallachiaandStephen the Great of Moldavia– were even able to defeat the Ottomans in major battles.[31]In Dobruja, which was included in theSilistra Eyalet,Nogai Tatarssettled and the local Gypsy tribes converted to Islam.[32]

The disintegration of the Kingdom of Hungary started with theBattle of Mohácson 29 August 1526.[33]The Ottomans annihilated the royal army andLouis II of Hungaryperished.[34]Rivalries between the partisans of the two newly elected kings –John ZápolyaandFerdinand of Habsburg– caused a civil war.[33]Ferdinand I's attempt to reunite the country after Zápolya's death provoked a new Ottoman campaign.[35]The Ottomans seizedBuda,the capital of Hungary, on 29 August 1541, but theOttoman SultanSuleiman the Magnificentgranted the lands east of the riverTiszato Zápolya's infant son,John Sigismund Zápolya.[35][36]The war between the two kings continued, enabling the Ottomans to expand their rule. The greater part of Banat fell to the Ottomans and was transformed into anOttoman province centered in Timişoarain 1552.[37][32]

Reformationspread in the lands under the rule of John Sigismund.[38][39]TheDiet of Turda of 1568declared that the "faith is a gift of God", allowing each village to freely elect their pastors.[40][41]In practise, only four denominations – Catholicism,Lutheranism,Calvinism,andUnitarianism– enjoyed a privileged status.[40][42][43]Orthodoxy and Judaism were only tolerated, and all other denominations were forbidden.[33][40][44]The Reformation also contributed to the spread and development of vernacular literature.[45]The first Romanian book (a Lutherancathecism) was printed inSibiuin 1544.[46]Decrees passed at the Diet of Transylvania were published in Hungarian from 1565.[47]John Sigismund renounced the title of king and adopted the new title of "Prince of Transylvaniaandparts of the Kingdom of Hungary"on 16 August 1570.[48]

The Romanian historianNicolae Iorgadescribed Wallachia and Moldavia asByzantium after Byzantium.[49]Indeed, especially after the disintegration of the Kingdom of Hungary, Byzantine cultural influence increased in both principalities.[49]Their rulers, who remained the only Orthodox monarchs inSoutheastern Europe,adopted the elements of the protocol of the one-time imperial court ofConstantinopleand supported Orthodox institutions throughout the Ottoman Empire.[49]The international status of the two principalities also changed in the 1530s and 1540s.[30]Although neither Wallachia nor Moldavia were integrated into theDar al-Islam,or "The Domain of Islam", the influence of the Ottoman Empire increased and the princes were prohibited to conclude treaties with foreign powers.[50]The Ottomans also hindered the princes from coining money, for which the use of foreign currency (especially Ottoman, Polish, Austrian, Venetian and Dutch coins) became widespread in Moldavia and Wallachia.[51]

A new war – the so-calledFifteen Years' War– broke out between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburgs in 1591.[52][53]Sigismund Báthory,prince of Transylvania, entered into an alliance withRudolph II, Holy Roman Emperorin 1595.[54]Michael the Brave,prince of Wallachia, accepted Báthory's suzerainty, agreeing that the Diet of Transylvania would introduce taxes in Wallachia.[55]Ştefan Răzvan,prince of Moldavia, also swore loyalty to Báthory who thus became the sovereign of the three principalities.[55]However, Ştefan Răzvan was soon dethroned, the Ottomans routed the Christian army in theBattle of Mezőkeresztesin October 1596 and Báthory abdicated in favor of Emperor Rudolph in April 1598.[55][56]Michael the Brave accepted the emperor's suzerainty, but Sigismund Báthory's cousin,Andrew Báthory,who seized Transylvania with Polish assistance, yielded to the Ottomans in the name of the three principalities in 1599.[57]

Michael the Brave invaded Transylvania and defeated Andrew Báthory in theBattle of Şelimbăron 28 October 1599.[58]He enteredAlba Iuliawhere the Diet recognized him as the Emperor's lieutenant.[58]Michael the Brave also occupied Moldavia in May 1600, uniting the three principalities under his rule.[57][59]However, the Transylvanian noblemen rose up against Michael the Brave and defeated him in theBattle of Mirăslăuon 18 September 1600.[60]The Poles invaded Moldavia and Wallachia, assistingIeremia MovilăandSimion Movilăto seize these principalities.[61]Michael the Brave tried to return with Emperor Rudolph's assistance, but he was murdered on 19 August 1601 nearCâmpia Turziiat the orders ofGiorgio Basta,the commander of the imperial troops.[60]The noblemen and nearly contemporaneous Hungarian and Saxon historians described Michael the Brave as a tyrant, willing to destroy the landowners with the assistance of Romanian and Székely commoners.[62]On the other hand, the personal union of Wallachia, Transylvania and Moldavia under his rule "became a symbol of Romanian national destiny"[63](the unification of the lands inhabited by Romanians) in the 19th century.[60][64]

End of the Fifteen Years War (1601–1606)[edit]

In Transylvania, extensive taxation, unpaid mercenaries' plundering raids, and attempts to spread Catholicism characterized the rule of Rudolph II's representatives.[65]The Ottomans supported pretenders, including Sigismund Báthory andMózes Székely,who tried to expel the imperial troops.[65][58]In Wallachia,Radu Șerban– the father-in-law of Michael the Brave's son – seized the throne with Rudolph II's support in July 1602.[66]A year later, he invaded Transylvania, defeated Mózes Székely and administered the principality in Emperor Rudolph's name until Giorgio Basta returned in September.[65][67]Moldavia remained under the rule of Ieremia Movilă who attempted to forge a reconciliation between the Ottomans and Poland.[68]

The changes and wars have turned [Transylvania] into desert. The boroughs and villages have been burned, most of the inhabitants and their cattle killed or driven away. In consequence, taxes, excise, bridge and road tolls yield but little, the mines are deserted, there are no hands to work.

— Giorgio Basta's letter of 1603[69]

An Italian imperial commander,Giacomo Belgiojoso,accused a wealthy Calvinist landowner,Stephen Bocskay,of treachery and ordered the forfeiture of his estates in Crişana in October 1604.[70][67]Bocskay hired at least 5,000Hajduks– a group of mainly Calvinist runaway serfs and noblemen who had settled in the borderlands – and rose up inopen rebellion.[69]After SultanAhmed Iappointed Bocskay prince of Transylvania, the Three Nations swore loyalty to him on 14 September 1605.[71]Bocskay's army invadedRoyal Hungaryand Austria, forcing theHabsburgsto sign thePeace of Viennaon 23 June 1606.[71]Rudolph II confirmed Bocskay's title of prince of Transylvania and granted four counties inUpper Hungaryto him.[72]

The Fifteen Years' War ended with thePeace of Zsitvatorok,which was signed in November 1606.[73]According to the treaty, Rudolph II acknowledged that the princes of Transylvania were subjected to the Sultans.[73]Bocskay, who had realized that only the autonomous status of Transylvania guaranteed the preservation of the liberties of the noblemen in Royal Hungary, emphasized that "as long as theHungarian Crownis with a nation mightier than ours, with the Germans,... it will be necessary and expedient to have a Hungarian prince in Transylvania ".[74]Bocskay died childless on 29 December 1606.[75]

Social changes after 1601[edit]

During Michael the Brave's brief tenure and the early years of Turkish suzerainty, the distribution of land in Wallachia and Moldavia changed dramatically.[76]Over the years, Wallachian and Moldavian princes made land grants to loyal boyars in exchange for military service so that by the 17th century hardly any land was left to be granted. Boyars in search of wealth began encroaching on peasant land and their military allegiance to the prince weakened. As a result, serfdom spread, successful boyars became more courtiers than warriors, and an intermediary class of impoverished lesser nobles developed. Would-be princes were forced to raise enormous sums to bribe their way to power, and peasant life grew more miserable as taxes and exactions increased.[76]Any prince wishing to improve the peasants' lot risked a financial shortfall that could enable rivals to out-bribe him at the Porte and usurp his position.[76]

According to the treaties (Capitulations) between the Romanian Principalities (Wallachia and Moldavia), Turkish subjects were not allowed to settle in the Principalities, to own land, to build houses ormosques,or to marry.[77]In spite of this restrictions imposed on the Turks, the princes allowed Greek and Turkish merchants and usurers to exploit the principalities' riches.

The three principalities under Ottoman rule[edit]

Principality of Transylvania (1606–1688)[edit]

Long winters and rainy summers with frequent floodings featured the "Little Ice Age"in 17th-century Transylvania.[78][79]Because of the short autumns,arable landson the plateaus were transformed intograzing lands.[78]The Fifteen Years' War had caused a demographic catastrophe.[79]For instance, the population decreased with about 80% in the lowland villages and with about 45% in the mountains in Solnocul de Mijloc andDăbâcaCounties during the wars; the two most important Saxon centers,SibiuandBrașov,lost more than 75% of their burghers.[79]The Diets often passed decrees that prescribed the return of runaway serfs to their lords or granted a six-year tax holiday for new settlers, but such decrees became rare from the 1620s, suggesting that a demographic regeneration had occurred in the meantime.[80]Nevertheless, epidemics –measlesandbubonic plague– which returned in each decade killed many peoples during the century.[78]

Bocskay designated a wealthy baron from Upper Hungary,Valentin Drugeth,as his successor.[81][82]The Ottomans supported Drugeth, but a member of the royalBáthory family,Gabriel Báthory,also claimed the throne.[81][82]Taking advantage of the two claimants' rivalry, the Diet electedSigismund Rákócziprince in early 1607.[83]A year later, Gabriel Báthory made an alliance with the Hajduks, forced Rákóczi to renounce and seized the throne.[81][84]Upon the Hajduk's demand, he promised that he would never secede from theHoly Crown of Hungary.[85]Radu Șerban of Wallachia andConstantin Movilăof Moldavia swore loyalty to Báthory.[86]Báthory's erratic behavior alienated both his subjects and the neighboring powers: he captured Sibiu and Brașov, and invaded Wallachia without the Sultan's approval.[87][88]TheSublime Portedecided to dethrone him and dispatchedGabriel Bethlento accomplish this task.[89]Bethlen invaded Transylvania accompanied by Ottoman, Wallachian andCrimean Tatartroops.[89]The Three Nations proclaimed him prince on 23 September 1613 and the Hajduks murdered his opponent.[89]

Transylvania prospered during Bethlen's reign.[90]He did not restrict the liberties of the Three Nations, but exercised royal prerogatives to limit their influence on state administration.[91]From 1615 at least two-thirds of those who attended the Diet were delegates appointed by him.[91][92]He introduced amercantilisteconomic policy, encouraging the immigration of Jews andBaptistcraftsmen from theHoly Roman Empire,creating state monopolies and promoting export.[41][93]The Diet controlled only about 10% of state revenues – around 70,000 florins from the annual income of about 700,000 florins – from the 1620s.[91]Bethlen set up a permanent army of mercenaries.[94]He forbade Székely communers from choosing serfdom to avoid military service in 1619 and increased the tax payable by Székely serfs in 1623.[95]He often granted nobility to serfs, but the Diet of 1619 requested him to stop this practise.[94]The Diet also prohibited the Romanians from bearing arms in 1620 and 1623.[94]Bethlen set up the first academy in Transylvania, promoted the building of schools and his subjects' studies abroad (especially in England), and punished those landowners who denied an education to children of serfs.[90]Laws prohibiting religious innovations were repeated in 1618 and the Diet obliged theSabbatarians– a community who adopted Jewish customs – to join one of the four official denominations.[96]He planned to convert the Romanians to Calvinism and tried to convinceCyril Lucaris,Patriarch of Constantinople, to assist him, but the latter refused, emphasizing the "blood ties" between the Romanians of Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia.[97]During theThirty Years' War,Bethlen made an alliance with theProtestant Unionand invaded Royal Hungary three times between 1619 and 1626.[98]He was elected king of Hungary in August 1620, but a year later he renounced this title.[99]In exchange, he received seven counties in Upper Hungary to rule during his lifetime.[100][101]

Bethlen died on 15 November 1629.[102]Conflicts between his widow and brother –Catherine of Brandenburgand Stephen Bethlen – enabledGeorge Rákóczi,Sigismund Rákóczi's son, to claim the throne for himself.[103]Rákóczi was proclaimed prince on 1 December 1630.[104]He did not continue Bethlen's mercantilism: state monopolies were abolished and taxes were lowered.[105]Instead, he expanded his own estates: he held 10 domains in 1630, but 18 years later he owned more than 30 large domains in Transylvania and Upper Hungary.[105][106]Rákóczi often accused his opponents of high treason, which enabled him to seize their property.[105]Especially Sabbatarian landowners were exposed to persecution.[107][96]For the Sabbatarians' teachings were based onAnti-Trinitariantheology, Rákóczi introduced a state control over the Unitarian Church in 1638.[96]Rákóczi invaded Royal Hungary andMoraviain 1644, but the Ottomans ordered him to retreat.[108]Even so,Ferdinand III of Hungaryagreed to grant him seven counties in Upper Hungary.[109]Transylvania was included in thePeace of Westphaliaamong the allies of England and Sweden.[109][110]

George I Rákóczi who died on 11 October 1648 was succeeded by his son,George II Rákóczi.[111][110]During his reign, thecodificationof the laws of the principality was accomplished with the publication of a law book (the so-calledApprobatae) in 1653.[112]TheApprobataeordered the landowners to capture all runaway commoners (especially the Ruthenians, Romanians and Wallachians who wandered in the country) and to force them to settle in their estates as serfs, prohibited the Romanians and the peasants to bear arms and obliged all Romanians to pay the tithe.[113]TheApprobataealso contained derogatory statements about the Romanians, stating that they were "admitted into the county for the public good".[114]Rákóczi who planned to acquire the Polish throne intervened in theSecond Northern Waron behalf of Sweden and invaded Poland in early 1657.[111][108]The Poles routed Rákóczi and his Moldavian and Wallachian allies, forcing them to withdraw.[111][115]On their route, a Crimean Tatar army annihilated Rákóczi's troops, capturing many of the leading noblemen.[116][117]

Rákóczi's action infuriated the newGrand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire,Köprülü Mehmed Pasha,who ordered his deposition in October 1657.[118]In the next years, princes supported by the Ottomans –Francis Rhédey,Ákos Barcsay,andMichael I Apafi– and their opponents – George II Rákóczi andJohn Kemény– fought against each other.[119]During this period the Ottomans capturedIneu,Lugoj,Caransebeș,andOradea,and destroyedAlba Iulia,the capital of the principality, and Crimean Tatars plundered theSzékely Land.[118][120]Although internal order was restored after John Kemény's death in a battle on 23 January 1662, Transylvania could never act as an independent state thereafter.[121][122]

Michael Apafi, who had been elected prince upon the Ottomans' demand on 14 September 1661, closely cooperated with the Diet throughout his reign.[123]He was the first prince to have invited the Orthodox bishop of Transylvania to the Diet.[123]Apafi declared salt mining a state monopoly and introduced a system oftax farming,which increased state revenues.[124]Upon his initiative, the decrees issued between 1653 and 1668 were revised and published in a new law code (theCompilatae) in early 1669.[125]Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperorsuspended the constitution of Royal Hungary and dismissed two-thirds of the Hungarian soldiers from the border forts.[126]The dismissed soldiers – known asKuruc– sought refuge in Transylvania.[126][127]Louis XIV of France,who waged a war against the emperor along theRhine,agreed to pay a subsidy to Apafi for his support of these outlaws in 1677 and 1678.[127][128]Apafi was forced to join the Ottoman armymarching against Viennain summer 1683, but he returned to Transylvania soon after the Ottomans were defeated on 12 September.[129]UponPope Innocent XI's initiative, Leopold I,John III Sobieski,King of Poland, and theRepublic of Veniceformed theHoly Leagueagainst the Ottoman Empire in early next year.[129]After the envoys of Apafi and Leopold I signed a treaty inCârțișoarain spring 1685, Transylvania became a secret member of the alliance.[130][131]According to the treaty, Apafi accepted the suzerainty of the Hungarian Crown, but Leopold I promised to respect the autonomous status of Transylvania.[130]These provisions were repeated in a new agreement which was signed in Vienna on 28 June 1686, but the new treaty also prescribed that imperial troops should be garrisoned inDevaandCluj.[132]Although the Diet refused to confirm the agreement, Apafi allowed the imperial troops to winter in Transylvania after a series of victories of the united army of the Holy League in autumn 1687.[133][131]Even so, Apafi did not fail to send the yearly tribute to the Sublime Porte at the end of the year.[131]Antonio Caraffa,commander of the imperial troops, forced the Three Nations to acknowledge the Habsburgs' hereditary rule and to allow to garrison imperial troops in the main towns.[133]The burghers ofBaia Mare,Brașov,Bistrița,and Sibiu denied to yield, but Caraffa submitted them by force in February 1688.[131]Leopold I was only willing to confirm the freedom of religion when Transylvanian delegates reminded him to his previous promises.[133]

New species of domesticated plants were introduced in Transylvania in the 17th century.Maize,which was first recorded in 1611, became a popular food in this period.[134]Tobacco was cultivated from the second half of the century, but the Diet passed decrees to regulate smoking already in 1670.[135]Hopswas introduced in the mountainous parts in the late 17th century.[134]Mining, which had declined in the previous centuries, flourished during Gabriel Bethlen's reign.[136]The Diet of 1618 decreed that both local and foreign miners could freely open new mines and exempted them of taxation.[137]Besides gold, silver and iron,mercuryextracted atAbrudandZlatnabecame an important source of state revenues.[138]Settlements destroyed during the Fifteen Years' War were restored between 1613 and 1648.[139]Because of the spread ofRenaissance architecture,the towns lost their medieval character in this period.[140]For instance, squares decorated with fountains or statues and parks were established in Alba Iulia andGilău, Cluj.[141]The villages also transformed: traditional huts disappeared and the new houses were divided into several rooms.[142]Excursions in the countryside became popular among townspeople in this century.[142]

Wallachia (1606–1688)[edit]

Radu Șerban concluded treaties with Sigismund Rákóczi and Gabriel Bethlen.[143]However, the latter invaded Wallachia, forcing Radu Șerban to flee in December 1610.[143]For Radu Șerban had adopted an anti-Ottoman policy, the Sublime Porte assistedRadu Mihneain seizing the throne in 1611.[144]Most boyars supported the new prince, which enabled him to repel Radu Șerban's attacks between 1611 and 1616.[145][143]The immigration of Greeks on a grand scale started during Radu Mihnea's reign.[146]Their financial background enabled them to buy landed property and acquire boyar status.[147]

The Sublime Porte transferred Radu Mihnea to Moldavia and appointedAlexandru Iliașprince of Wallachia in 1616.[146]Two years later, the new ruler's blatant favoritism towards the Greeks caused an uprising during which the discontented native noblemen, who were led byLupu Mehedițeanu,murdered Greek landowners and merchants.[146][148]The turmoil enabledGabriel Movilăto seize the throne.[146]He was expelled in 1620 by Radu Mihnea, who thus united Wallachia and Moldavia under his rule.[146]TheOttoman SultanOsman IIinvaded Poland and laid siege toHotin(now Khotyn in Ukraine) in September 1621.[149]After the Poles relieved the fort,[149]Radu Mihnea who had accompanied the Sultan mediated a peace treaty between the two parties.[146]Radu Mihnea appointed his son,Alexandru Coconul,prince of Wallachia in 1623.[146]Four years later Alexandru Iliaș seized the throne for the second time.[146]

During the reign ofLeon Tomșa,who mounted the throne in 1629, a new anti-Greek uprising started.[148]On 19 July 1631 the rebellious boyars, who were supported by George I Rákóczi,[146]forced Leon Tomșa to expel all Greeks who had not married a local woman and did not held landed property in Wallachia.[147][148]The prince also exempted the boyars of taxation and confirmed their property rights.[147]A year later, the Sublime Porte dethroned Leon Tomșa and appointed Alexandru Iliaș's son,Radu Iliaș,prince.[146]In fear of growing Greek influence, the boyars offered the throne to one of their number,Matei Brâncoveanu,in August 1632.[150]Matei Brâncoveanu, who had fled to Transylvania during Leon Tomșa's reign, returned to Wallachia and defeated Radu Iliaș atPlumbuitain October.[103]He convinced the Sublime Porte to confirm his rule; in exchange, he had to increase the amount of the yearly tribute from 45,000 to 135,000thalers.[103]Stating that he was a grandson of a former prince,Neagoe Basarab,he changed his name and reigned as Matei Basarab from September 1631.[103]

Matei Basarab closely cooperated with the boyars throughout his reign.[151]He regularly convoked their assembly and strengthened the boyars' control of the peasants who worked on their estates.[147]Uppon his initiative, the copper mine atBaia de Aramăand the iron mine atBaia de Fierwere reopened, and twopaper millsand a glasswork were built.[152]He stopped farming out the revenues from salt mining and custom duties and introduced a new system of taxation.[153]The latter reform increased the tax burden to such an extent that many of the serfs fled from Wallachia.[153]In response, Matei Basarab levied the taxes that the serfs who left the village would have paid upon those who stayed behind.[153]Increasing state revenues enabled him to finance the erection or renovation of 30 churches and monasteries in Wallachia and onMount Athos.[153]He established the first institution of higher education – a college inTârgoviște– in Wallachia in 1646.[154]He set up an army of mercenaries.[153]Matei Basarab concluded a series of treaties with George I and II Rákóczi between 1635 and 1650, promising to pay a yearly tribute.[153]In exchange, both princes assisted him againstVasile Lupuof Moldavia who made several attempts to expand his authority over Wallachia.[153]Excessive taxation and the prince's failure to satisfy his soldiers' demands for higher salary caused a revolt at the end of his rule.[155]He died on 9 April 1654.[156]

Ten days later, the boyars electedConstantin Șerban– Radu Șerban's illegitimate son – prince.[157]Upon the boyars' demand, the new ruler dismissed many soldiers, causing a new riot in February 1655.[157]The discontentedmusketeersand local guards – theseimenianddorobanți–[158]joined the rebellious serfs and attacked boyars' courts.[157][159]The prince sought the assistance of George II Rákóczi andGeorge Stephen of Moldavia.[157]Their united army routed the rebels on theTeleajen Riveron 26 June, but smaller groups of the dismissed soldiers continued to fight until their leader,Hrizea of Bogdănei,was killed in 1657.[157]Constantin Șerban acknowledged George II Rákóczi's suzerainty in 1657.[157]After Rákóczi's fall, the Sublime Porte dethroned Constantin Șerban and installedMihnea III,who was allegedly Radu Mihnea's son, as the new prince in early 1658.[157]However, the latter formed an anti-Ottoman alliance with George II Rákóczi and Constantin Șerban, who had in the meantime seized Moldavia.[160]He defeated the Ottomans atFrăteștion 23 November 1659, but a joint invasion of the Ottomans and the Crimean Tatars forced him to flee to Transylvania.[160][157]

The boyars, who were sharply opposed to Mihnea III's anti-Ottoman policy, exerted a powerful influence on state administration after his fall.[161]The boyars formed two parties, which were centered around theCantacuzinoandBălenifamilies.[162][163]George Ghicawas proclaimed prince in December 1659, but he soon renounced in favor of his son,Gregory.[164]The young prince governed with Constantine Cantacuzino's assistance.[164]Gregory Ghica took part in the Ottoman campaign against Royal Hungary in 1663 and 1664.[164]However, the Ottomans received information of his secret correspondence with the Habsburgs, forcing him to flee for Vienna.[164]The Sublime Porte appointedRadu Leon,who was Leon Tomșa's son, prince.[164]He favored the Greeks, but the boyars forced him to repeat his father's decree against them.[164][165]He was dethroned in March 1669, and the Catacuzinos' puppet,Anthony of Popeşti,was declared prince.[164][162]The Sublime Porte reinstalled George Ghica on the throne in 1672.[164]He accompanied theOttomans against Poland in 1673,but let himself captured by the Poles, which contributed to the Ottomans' defeat in theBattle of Khotynon 11 November 1673.[164][166]The Ottomans dethroned Ghica and appointedGeorge Ducas– a Greek fromIstanbul– prince.[164][167]Ghica promoted new boyar families – theCuparescufrom Moldavia and theLeurdeni– to counterbalance the Cantacuzinos' influence.[168]However, the Sublime Porte transferred Ducas to Moldavia and appointed the wealthyȘerban Cantacuzinoprince.[168]

The new prince who wanted to restore the monarchs' absolut power captured and executed many members of the Băleni family.[169]He set up a school for higher education and invited Orthodox scholars from the Ottoman Empire to teach philosophy, natural sciences and classical literature.[170]He supported the Ottomans during the siege of Vienna in 1683, but also negotiated with the Christian powers.[171]In fear of the Habsburgs' attempts to promote Catholicism, Cantacuzino tried to forge an alliance with Russia.[172]After imperial troops took control of Transylvania in 1688, Cantacuzino was willing to accept Leopold I's suzerainty in exchange for the Banat and the acknowledgement of his descendants' hereditary rule in Wallachia, but his offers were refused.[171][173]The negotiations were still in progress when Cantacuzino died unexpectedly in October.[171][173]

The spread ofhans– inns protected by walls – in the 17th century shows the important role of commerce.[174]For instance, according to foreign travelers' accounts, there were sevenhansin Bucharest in 1666.[174]Șerban Cantacuzino, who especially promoted commerce, had new roads and bridges built throughout the country.[152]Maize was also introduced in Wallachia upon his initiative.[168]Lofty mansions built for the Cantacuzinos atMăgureniandFilipeștiin the middle of the century show the boyars' increasing wealth.[174]

Moldavia (1606–1687)[edit]

Ieremia Movilă, who gave his daughters to Polish magnates in marriage, held firm to his alliance with Poland, but never turned against the Ottoman Empire.[68]He achieved that both Poland and the Ottomans acknowledged his family's hereditary right to the throne, but after his death in summer 1606, the boyars tried to hinder his son, Constantine, from seizing the throne.[175][68]The young prince,whose motherwas famed for her political skills,[86]only mounted the throne at the end of 1607.[175]Constantin Movilă strengthened his alliance with Poland, Transylvania and Wallachia, which irritated the Ottomans.[68]The Sublime Porte replaced him withStephen II Tomșain September 1611.[68]After Constantin Movilă's unsuccessful attempt to return with Polish support, Stephen Tomșa introduced a policy ofterror,executing many boyars.[176][177]The boyars rose up in open rebellion with Polish assistance and dethroned the prince in favor ofAlexander Movilăin November 1615.[178]The Ottomans stepped in, assisting Radu Mihnea, who had pacified Wallachia, to seize the throne in 1616.[177][178]

Moldavia was included in thePeace of Busza,signed in September 1617, between Poland and the Ottoman Empire, which obliged Poland to cede thefortress of Hotinto Moldavia and to give up supporting Radu Mihnea's opponents.[178]In the same year, peasant uprisings started in many places because of the increased taxation.[178]The Sublime Porte granted Moldavia toGaspar Graziani,a Venetian adventurer, in 1619.[178]He attempted to forge an anti-Ottoman alliance with Poland and the Habsburgs, but a group of boyars murdered him in August 1620.[178][179]In the following one and half decades six princes – Alexandru Iliaș, Stephen Tomșa, Radu Mihnea,Miron Barnovschi-Movilă,Alexandru Coconul, andMoise Movilă– succeeded on the throne.[175]Barnovschi-Movilă ordered that runaway serfs be returned to their lords.[178]An uprising of the peasantry forced Alexandru Iliaș to abdicate in 1633, and the mob massacred many of his Greek courtiers.[148]

A period of stability commenced when Vasile Lupu mounted the throne in 1634.[180]He was ofAlbanianorigin and received a Greek education, but he was proclaimed prince after an anti-Greek rebellion.[181]Lupu Vasile regarded himself as theByzantine emperors' successor and introduced anauthoritarianregime.[182][183]He gained the support of both the pro-Polish and the pro-Ottoman boyars,[184]but also strengthened the Greeks' position through farming out state revenues and supporting their acquisition of landed property.[172]He set up a college inIașiin 1639 and promoted the establishment of the first printing press in Moldavia three years later.[185]He was planning to unite Moldavia and Transylvania under his rule and invaded Matei Basarab's Moldavia four times between 1635 and 1653, but achieved nothing.[184]He attacked theCossacksand the Crimean Tatars who marched through Moldavia after their campaigns against Poland in 1649.[184]In retaliation, the Cossacks and the Tatars jointly invaded Moldavia in the next year.[186]HetmanBohdan Khmelnytskypersuaded Vasile Lupu to marry his daughter, Ruxandra, to the Hetman's son,Tymofiyin 1652.[186]Vasile Lupu was overthrown in a military coup thatlogofătGeorge Stephen organized against him with Transylvanian and Wallachian assistance in early 1653.[184]Tymofiy Khmelnytsky supported him to return, but their troops were defeated in the Battle of Finta on 27 May.[184]

George Stephen dismissed Vasile Lupu's relatives from the highest offices.[121]He spent enormous sums to pay his mercenaries, but could not hinder the latter from pillaging the countryside or fighting against each other.[121]Although the Sublime Porte forbade him to support George II Rákóczi, he sent a troop of 2,000 to accompany Rákóczi to Poland.[187]In retaliation, the Porte dethroned George Stephen and placed George Ghica on the throne in 1659.[121]

17th–18th centuries[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(November 2021) |

Although centuries of continued attacks and raids from Turks, Tatars, Poles, Hungarians, and Cossacks, had crippled Moldavia and Wallachia and caused economical and human losses, the two countries were relatively adapted to this type of warfare. During the second half of the 17th century, Poland suffered a similar series of attacks: Swedish, Cossack and Tartar attacks ultimately left Poland in ruin, and it lost its place as a Central European power (seeThe Deluge).

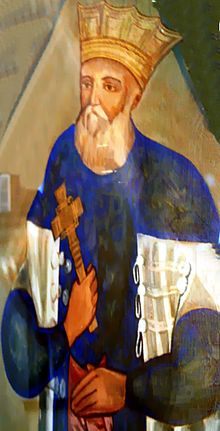

(1673–1723)

(1654–1714)

CatholicPoland and Hungary, which despite being Christian countries, constantly tried to take control of theEastern OrthodoxMoldavia and Wallachia. A new possible ally was Russia, which apparently posed no danger to Moldavia, for geographic and religious reasons.

During the early 17th century, Moldavia had unfortunate experiences in their efforts for Russian assistance fromIvan IIIandAlexis Michaelovitchagainst the Turks and Tatars. UnderPeter the Great,Russia's strength and influence had grown, and it seemed to be an excellent ally for Moldavia. Numerous Moldavians and Wallachians enlisted in Peter's army, which contained one squadron made up only of Romanian cavalry. UnderConstantin Cantemir,Antioh CantemirandConstantin Brâncoveanu,Moldavia and Wallachia hoped that with Russian help they might drive out the Turks from the border cities (Chilia,Cetatea Albă).

Charles XII of Sweden,after his defeat in 1709 at theBattle of Lesnaya,sought refuge inTighina,a border fort of the Turkish vassal state of Moldavia, guarded by Ottoman troops. As a response, Peter came to Iaşi in 1710. There he re-signed the Russian-Moldavian treaty of alliance (previously signed atLutskon 24 April 1711), which provided for the hereditary leadership his close friendDimitrie Cantemir(son of Constantin Cantemir and brother of Antioh Constantin) who was supposed to bear the title of Serene Lord of the land of Moldavia, Sovereign, and Friend (Volegator) of the land of Russia, but not as a subject vassal, as under the Ottomans. Although at that time Russia's western border was the SouthernBug River,the treaty stipulated that theDniestershould be the boundary between Moldavia and the Russian Empire and that theBudjakwould belong to Moldavia. The country was to pay not a cent of tribute. The Tsar bound himself not to infringe the rights of the Moldavian sovereign, or whoever might succeed him. Considering him the savior of Moldavia, the boyars held a banquet in honor of the Tsar and to celebrate the treaty.

In response, a great Ottoman army approached along the Prut and, at theBattle of Stanilestiin June 1711, the Russian and Moldavian armies were crushed. The war was ended by theTreaty of the Pruthon July 21, 1711. The Grand Vizier imposed drastic terms. The treaty stipulated that Russian armies would abandon Moldavia immediately, renounce its sovereignty over theCossacks,destroy the fortresses erected along the frontier, and restoreOtchakovto the Porte. Moldavia was obliged to assist at and to support all expenses for the reinforcements and supplies that traversed Moldavian territory. Prince Cantemir, many of his boyars[188]and much of the Moldavian army had to take refuge in Russia.

As a result of their victory of the 1711 war, the Turks placed a garrison inHotin,rebuilt the fortress under the direction of French engineers, and made the surrounding region into asanjak.Moldavia was now shut in by Turkish border strips at Hotin, Bender, Akkerman, Kilia, Ismail and Reni. The new sanjak was the most extensive on Moldavian territory, comprising a hundred villages and the market-towns of Lipcani-Briceni and Suliţa Noua. Under the Turks, Bessarabia and Transnistria witnessed a constant immigration from Poland and Ukraine, of Ukrainian speaking landless peasants, largely fugitives from the severe serfdom that prevailed there, to the districts of Hotin and Chişinău.

The existing Moldavians in the Russian armies were joined by newly joined Moldavian and Wallachian Hussars (Hansari in theRomanian language) from the1735–39 war.When Field MarshalBurkhard Christoph von Münnichentered Iaşi, the capital of Moldavia, Moldavian auxiliary troops on Turkish service changed side and joined the Russians. They were officially constituted into the "Regiment number 96 – Moldavian Hussars" ( "Moldavskiy Hussarskiy Polk" ), under Prince Cantemir, on October 14, 1741. They took part in the 1741–43 war with Sweden, and the 1741 and 1743 campaigns at Wilmanstrand andHelsinki.During theSeven Years' Warthey fought at theBattle of Gross-Jägersdorf(1757),Battle of Zorndorf(1758),Battle of Kunersdorf(1759) and the 1760 capturing of Berlin.

Phanariots[edit]

An important demand of the Treaty of Prut was that Moldavia and Wallachia would have only appointed rulers. The Phanariots would be appointed asHospodarsfrom 1711 to 1821. The late 18th century is regarded as one of the darkest time inRomanian history.The main goal of most Phanariots was to get rich and then to retire.

Under the Phanariots, Moldavia was the first state in Eastern Europe to abolish serfdom, whenConstantine Mavrocordatos,summoned the boyars in 1749 to a great council in the church of the Three Hierarchs inIași.In Transylvania, this reform did not take place until 1784, as a consequence of the bloody revolt of the Romanian peasantry under Horea, Cloşca and Crişan. Bessarabia was now still more attractive to the Polish and Russian serfs. The former had to serve their masters free for 150 days every year, and the latter were virtually slaves. Clandestine immigration from Poland and the Ukraine flowed particularly to the boundaries of Bessarabia, around Hotin and Cernăuţi.

Russian expansion[edit]

By the late 18th century and early 19th century, Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania found themselves as a clashing area for three neighboring empires: the Habsburg Empire, the newly appeared Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire.

In 1768, a six-year war broke out between Russia and Turkey (seeRusso-Turkish War (1768–74)). The Russians took Hotin, Bender and Iaşi, and occupied Moldavia the whole extent of the war. In 1772, the partition of Poland gave Galicia and Lodomeria to Austria, and Volhynia and Podolia to Russia, so that Moldavia was now in immediate contact with the Austrian and Russian Empires. In thePeace of Kuchuk-Kainarji(1774) Turkey ceded to Russia the country between Dnieper and Bug, but retained the Bessarabian border fortresses and their sanjaks. Moldavia kept its independence, under Turkish suzerainty, as before. Catherine self-assumed the right of protecting the Christians of the Romanian Principalities.

In 1775, Empress Maria Theresa of theHabsburg monarchytook advantage of the situation and occupied the northern extremity of Moldavia, calledBucovina,marching the Austrian armies throughCernăuţiandSuceava,considered the holy city of Moldavia, as it preserved the tombs of Stephen the Great and other Moldavian rulers. The occupation was acknowledged with a treaty between the Habsburg Empire and the Ottoman Empire, despite the protests ofGrigore Ghica,the Hospodar of Moldavia. Grigore Ghica was assassinated in 1777, at Iaşi, by Austrian paid Turkish troops.

In 1787, Russia and Austria declared war on Turkey (seeRusso-Turkish War (1787–92)). Empress Catherine wished to installGrigori Alexandrovich Potemkinas Prince ofDacia,a Russian vassal state corresponding to the ancient Roman Dacia, and thus to approach her final goal, Constantinople. In 1788 war started, but Turkey's preparations were inadequate and the moment was ill-chosen, now that Russia and Austria were in alliance. After a long list of failures, the Ottomans were forced to surrender. The Peace Treaty was signed at Iaşi (see theTreaty of Jassy) in January 1792. It stipulated that the Moldavia shall remain a Turkish vassal, that Dniester was the frontier between Moldavia and the Russian Empire, and that the Budjak shall pass under Russian control.

In 1806,Napoleon I of FranceencouragedCzar Alexander Pavlovitchto begin another war with Turkey. Russian troops occupied again Moldavia and Wallachia under GeneralKutuzovwho was made Governor-General of the Romanian Principalities. The foreign consuls and diplomatic agents had to leave the capital cities of Iaşi and Bucharest. After the Russians broke the truce with a surprise attack, the Ottomans entered peace negotiations. AtGiurgiuand atBucharest(seeTreaty of Bucharest (1812)), the Russians annexed the Budjak and the eastern part of Moldavia, which was called Bessarabia.

Bessarabia and Bukovina[edit]

Bessarabia, which according to the official Russian census of 1816, 92.5% of the population was Romanian (419,240 Romanians, 30,000 Ukrainians, 19,120 Jews, 6,000 Lipovans), would be held by Russia until 1918. During this time, the percentage of the Romanian population of the area decreased because of the politics of colonization pursued by the Russian government. In the first years following the annexation, several thousand peasant families fled beyond the Pruth out of fear that the Russian authorities would introduce serfdom.[189]This was one of the reasons behind the decision of the Russian government not to extend the regime of serfdom into Bessarbia.

During the first fifteen years after the annexation, Bessarabia enjoyed some measure of autonomy on the basis of "Temporary Rules for the Government of Bessarabia" of 1813 and more fundamentally, "the Statute for the Formation of Bessarbian Province" that was introduced by Alexander I during his personal visit to Chisinau in the spring of 1818. Both documents stipulated that the dispensation of justice is made on the basis of local laws and customs as well as the Russian laws. Romanian was used alongside Russian as the language of administration. The province was placed under the authority of a viceroy who governed together with the Supreme Council formed in part through election from the ranks of the local nobility. A considerable number of positions in the district administration were likewise filled through election. Bessarbia's autonomy was considerably reduced in 1828 when, on the representation of the governor general of New Russia and the viceroy of Bessarabia Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, Nicholas I adopted a new statute which abolished the Supreme Council and reduced the number of elected positions in the local administration.

In parallel, the Russian government pursued the policy of colonization. On 26 June 1812, TsarAlexander Ipromulgated the Special Colonization Status of Bessarabia. Bulgarians, Gagauz, Germans, Jews, Swiss and French colonists were brought in. In 1836, the Russian language was imposed as official administration, school and church. Initially an aspect of administrative unification of Bessarabia with the rest of the empire, the promotion of the Russian language in the public sphere became a full-fledged policy of Russification by the end of the 19th century, when the Russian government adopted repressive policies towards local Romanian intellectuals.

Bukovina (including North Bukovina) at that time (1775) had a population of 75,000 Romanians and 12,000 Ukrainians, Jews and Poles. It was annexed to the Habsburg-held province of Galicia, and colonized by Ukrainians, Germans, Hungarians, Jews and Armenians. They were granted free lands and exclusion from paying any taxes. Between 1905 and 1907, 60,000 Romanians were promised more land, and were sent to Siberia and the Central Asian provinces. Instead, further Belarusians and Ukrainians were brought in. The official languages in school and administration were German and Polish.

Transylvania[edit]

The Habsburgs[edit]

In 1683Jan Sobieski's Polish army crushed an Ottoman army besiegingVienna,and Christian forces soon began the slow process of driving the Turks from Europe. In 1688 the Transylvanian Diet renounced Ottoman suzerainty and accepted Austrian protection. Eleven years later, the Porte officially recognized Austria's sovereignty over the region. Although an imperial decree reaffirmed the privileges of Transylvania's nobles and the status of its four "recognized" religions, Vienna assumed direct control of the region and the emperor plannedannexation.[190]

The Romanian majority remained segregated from Transylvania's political life and almost totally enserfed; Romanians were forbidden to marry, relocate, or practice a trade without the permission of their landlords. Besides oppressive feudal exactions, the Orthodox Romanians had to pay tithes to the Roman Catholic or Protestant church, depending on their landlords' faith. Barred from collecting tithes, Orthodox priests lived in penury, and many labored as peasants to survive.[190]

Under Habsburg rule, Roman Catholics dominated Transylvania's more numerous Protestants, and Vienna mounted a campaign to convert the region to Catholicism. The imperial army delivered many Protestant churches to Catholic hands, and anyone who broke from the Catholic Church was liable to receive a public flogging. The Habsburgs also attempted to persuade Orthodox clergymen to join theRomanian Greek-Catholic Church,which retained Orthodox rituals and customs but accepted four key points of Catholic doctrine and acknowledged papal authority.[190]

Jesuitsdispatched to Transylvania promised Orthodox clergymen heightened social status, exemption from serfdom, and material benefits. In 1699 and 1701, EmperorLeopold Idecreed Transylvania's Orthodox Church to be one with the Roman Catholic Church; the Habsburgs, however, never intended to make Greek-Catholicism a "received" religion and did not enforce portions of Leopold's decrees that gave Greek-Catholic clergymen the same rights as Roman Catholic priests. Despite an Orthodox synod's acceptance of union, many Orthodox clergy and faithful rejected it.[190]

In 1711, having suppressed an eight-year rebellion of Hungarian nobles and serfs, the Austrian empire consolidated its hold on Transylvania, and within several decades the Greek-Catholic Church proved a seminal force in the rise of Romanian nationalism. Greek-Catholic clergymen had influence in Vienna; and Greek-Catholic priests schooled in Rome and Vienna acquainted the Romanians with Western ideas, wrote historiestracing their Daco-Romanorigins, adapted theLatin Alpha betto theRomanian language(seeRomanian Alpha bet), and publishedRomanian grammarsand prayer books. The Romanian Greek-Catholic Church's seat atBlaj,in southern Transylvania, became a center ofRomanian culture.[190]

The Romanians' struggle for equality in Transylvania found its first formidable advocate in a Greek-Catholic bishop,Inocenţiu Micu-Klein,who, with imperial backing, became abaronand a member of the Transylvanian Diet. From 1729 to 1744, Klein submitted petitions to Vienna on the Romanians' behalf and stubbornly took the floor of Transylvania's Diet to declare that Romanians were the inferiors of no other Transylvanian people, that they contributed more taxes and soldiers to the state than any of Transylvania's "nations", and that only enmity and outdated privileges caused their political exclusion and economic exploitation. Klein fought to gain Greek-Catholic clergymen the same rights as Roman Catholic priests, reduce feudal obligations, restore expropriated land to Romanian peasants, and bar feudal lords from depriving Romanian children of an education.

The bishop's words fell on deaf ears in Vienna; and Hungarian, German, and Szekler deputies, jealously clinging to their noble privileges, openly mocked the bishop and snarled that the Romanians were to the Transylvanian body politic what "moths are to clothing". Klein eventually fled to Rome where his appeals to the Pope proved fruitless. He died in a Roman monastery in 1768. Klein's struggle, however, stirred both Greek-Catholic and Orthodox Romanians to demand equal standing. In 1762 an imperial decree established an organization for Transylvania's Orthodox community, but the empire still denied Orthodoxy equality even with the Greek-Catholic Church.[190]

The Revolt of Horea, Cloşca and Crişan[edit]

EmperorJoseph II(ruled 1780–90), before his accession, witnessed the serfs' wretched existence during three tours of Transylvania. As emperor he launched an energetic reform program. Steeped in the teachings of theFrench Enlightenment,he practised "enlightened despotism,"or reform from above designed to preempt revolution from below. He brought the empire under strict central control, launched an education program, and instituted religious tolerance, including full civil rights for Orthodox Christians. In 1784, Transylvanian serfs underHorea, Cloşca and Crişan,convinced they had the Emperor's support, rebelled against their feudal masters, sacked castles and manor houses, and murdered about 100 nobles. Joseph ordered the revolt repressed, but granted amnesty to all participants except their leaders, whom the nobles tortured and put to death in front of peasants brought to witness the execution. Joseph, aiming to strike at the rebellion's root causes, emancipated the serfs, annulled Transylvania's constitution, dissolved the Union of Three Nations, and decreedGermanas the official language of the empire. Hungary's nobles and Catholic clergy resisted Joseph's reforms, and the peasants soon grew dissatisfied with taxes, conscription, and forced requisition of military supplies. Faced with broad discontent, Joseph rescinded many of his initiatives toward the end of his life.[191][192]

Joseph II'sGermanizationdecree triggered a chain reaction of national movements throughout the empire. Hungarians appealed for unification of Hungary and Transylvania andMagyarizationof minority peoples.[citation needed][dubious–discuss]Threatened by both Germanization and Magyarization, the Romanians and other minority nations experienced a cultural awakening. In 1791 two Romanian bishops—one Orthodox, the other Greek-Catholic—petitioned Emperor Leopold II (ruled 1790–92) to grant Romanians political and civil rights, to place Orthodox and Greek-Catholic clergy on an equal footing, and to apportion a share of government posts for Romanian appointees; the bishops supported their petition by arguing that Romanians were descendants of the Romans and the aboriginal inhabitants of Transylvania. The Emperor restored Transylvania as a territorial entity and ordered the Transylvanian Diet to consider the petition. The Diet, however, decided only to allow Orthodox believers to practise their faith; the deputies denied the Orthodox Church recognition and refused to give Romanians equal political standing alongside the other Transylvanian nations.[191]

Leopold's successor,Francis I(1792–1835), whose almost abnormal aversion to change and fear of revolution brought his empire four decades of political stagnation, virtually ignored Transylvania's constitution and refused to convoke the Transylvanian Diet for twenty-three years. When the Diet finally reconvened in 1834, the language issue reemerged, as Hungarian deputies proposed makingMagyar(Hungarian) the official language of Transylvania. In 1843 the Hungarian Diet passed a law making Magyar Hungary's official language, and in 1847 the Transylvanian Diet enacted a law requiring the government to use Magyar. Transylvania's Romanians protested futilely.[191]

At the end of the 17th century, following the defeat of the Turks, Hungary and Transylvania become part of theHabsburg monarchy.The Austrians, in turn, rapidly expanded their empire: in 1718 an important part of Wallachia, calledOltenia,was incorporated into the Austrian Empire as theBanat of Craiovaand was only returned in 1739.

Towards independence[edit]

See also[edit]

- List of Wallachian rulers(up to 1859)

- List of Moldavian rulers(up to 1859)

- List of Transylvanian rulers(up to 1918)

References[edit]

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,pp. 151–155.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 51.

- ^abcPop 1999,p. 41.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,pp. 36, 80, 125–126, 202.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,pp. 135–136, 218.

- ^Fine 1994,p. 367.

- ^Georgescu 1991,pp. 33–35.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 83.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 97.

- ^Georgescu 1991,p. 48.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,pp. 84–86.

- ^Pop 1999,p. 52.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,p. 46.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,pp. 84–88.

- ^abHitchins 2014,p. 25.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,pp. 139, 167, 176, 214.

- ^Crowe 2007,p. 109.

- ^Pop 1999,pp. 53–54.

- ^Cartledge 2011,pp. 39–40.

- ^Makkai 1994,pp. 215–216.

- ^abPop 1999,p. 54.

- ^Kontler 1999,pp. 109–110.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,pp. 44–45.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 110.

- ^Pop 2013,p. 284.

- ^Georgescu 1991,p. 53.

- ^Pop 1999,p. 60.

- ^Fine 1994,p. 423.

- ^Hitchins 2014,pp. 26, 29.

- ^abHitchins 2014,p. 30.

- ^Pop 1999,pp. 63–66.

- ^abAndea 2005,p. 316.

- ^abcCartledge 2011,p. 81.

- ^Stavrianos 2000,p. 76.

- ^abKontler 1999,p. 142.

- ^Cartledge 2011,p. 83.

- ^Barta 1994,p. 258.

- ^Pop 1999,p. 69.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 151.

- ^abcBarta 1994,p. 290.

- ^abCartledge 2011,p. 92.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 152.

- ^Georgescu 1991,p. 41.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 148.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 154.

- ^Hitchins 2014,p. 41.

- ^Barta 1994,p. 292.

- ^Barta 1994,p. 259.

- ^abcGeorgescu 1991,p. 59.

- ^Hitchins 2014,pp. 30–31.

- ^Georgescu 1991,p. 27.

- ^Stavrianos 2000,p. 160.

- ^Kontler 1999,pp. 160–162.

- ^Barta 1994,p. 294.

- ^abcBolovan et al. 1997,p. 144.

- ^Barta 1994,p. 295.

- ^abBolovan et al. 1997,p. 147.

- ^abcBarta 1994,p. 296.

- ^Hitchins 2014,p. 35.

- ^abcTreptow & Popa 1996,p. 131.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,pp. 150–151.

- ^Prodan 1971,pp. 84–89.

- ^Hitchins 2014,p. 31.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 151.

- ^abcAndea 2005,p. 322.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 317.

- ^abBarta 1994,p. 297.

- ^abcdeAndea 2005,p. 320.

- ^abCartledge 2011,p. 102.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 165.

- ^abBarta 1994,p. 298.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 167.

- ^abStavrianos 2000,p. 161.

- ^Barta 1994,p. 299.

- ^Barta 1994,p. 300.

- ^abcThe Ottoman Invasionsin U.S. Library of Congress country study on Romania (1989, Edited by Ronald D. Bachman).

- ^Dungaciu & Manolache 2019,p. xi.

- ^abcRüsz Fogarasi 2009,p. 182.

- ^abcPéter 1994,p. 301.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 301–302.

- ^abcAndea 2005,p. 323.

- ^abPéter 1994,p. 303.

- ^Péter 1994,p. 304.

- ^Péter 1994,p. 305.

- ^Péter 1994,p. 307.

- ^abPéter 1994,p. 306.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 168.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 309, 312–313.

- ^abcPéter 1994,p. 313.

- ^abCartledge 2011,p. 93.

- ^abcPéter 1994,p. 316.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 325.

- ^Szegedi 2009,p. 110.

- ^abcAndea 2005,p. 326.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 335–336.

- ^abcSzegedi 2009,p. 109.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,pp. 163–164.

- ^Andea 2005,pp. 327–328.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 321–322.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 327.

- ^Kontler 1999,p. 171.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 328.

- ^abcdAndea 2005,p. 329.

- ^Péter 1994,p. 326.

- ^abcPéter 1994,p. 329.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 334.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 328, 351.

- ^abCartledge 2011,p. 108.

- ^abAndea 2005,p. 335.

- ^abPéter 1994,p. 332.

- ^abcAndea 2005,p. 337.

- ^Dörner 2009,p. 159.

- ^Prodan 1971,pp. 100–101.

- ^Prodan 1971,p. 12.

- ^Péter 1994,p. 355.

- ^Cartledge 2011,pp. 108–109.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 355–356.

- ^abPéter 1994,p. 357.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 338.

- ^R. Várkonyi 1994,p. 359.

- ^abcdAndea 2005,p. 339.

- ^Cartledge 2011,p. 109.

- ^abR. Várkonyi 1994,p. 363.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 352.

- ^Dörner 2009,p. 160.

- ^abCartledge 2011,pp. 111–112.

- ^abKontler 1999,p. 179.

- ^Andea 2005,p. 353.

- ^abR. Várkonyi 1994,p. 367.

- ^abR. Várkonyi 1994,p. 368.

- ^abcdAndea 2005,p. 354.

- ^R. Várkonyi 1994,p. 369.

- ^abcR. Várkonyi 1994,p. 370.

- ^abRüsz Fogarasi 2009,p. 187.

- ^Rüsz Fogarasi 2009,p. 188.

- ^Rüsz Fogarasi 2009,p. 194.

- ^Rüsz Fogarasi 2009,p. 195.

- ^Rüsz Fogarasi 2009,p. 196.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 339–340.

- ^Péter 1994,p. 340.

- ^Péter 1994,pp. 340–341.

- ^abPéter 1994,p. 341.

- ^abcAndea 2005,p. 318.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,pp. 164–165.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 165.

- ^abcdefghijAndea 2005,p. 319.

- ^abcdHitchins 2014,p. 43.

- ^abcdBolovan et al. 1997,p. 167.

- ^abDavies 1982,p. 460.

- ^Andea 2005,pp. 319, 329.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 168.

- ^abGeorgescu 1991,p. 24.

- ^abcdefgAndea 2005,p. 330.

- ^Georgescu 1991,pp. 62–63.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,p. 128.

- ^Andea 2005,pp. 330–332.

- ^abcdefghAndea 2005,p. 340.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,pp. 90, 181.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 171.

- ^abBolovan et al. 1997,p. 173.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 175.

- ^abBolovan et al. 1997,p. 176.

- ^Georgescu 1991,p. 36.

- ^abcdefghijAndea 2005,p. 341.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 177.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 179.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,pp. 179–180.

- ^abcAndea 2005,p. 342.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 180.

- ^Georgescu 1991,p. 64.

- ^abcAndea 2005,p. 343.

- ^abHitchins 2014,p. 45.

- ^abGeorgescu 1991,p. 57.

- ^abcGeorgescu 1991,p. 70.

- ^abcTreptow & Popa 1996,p.liii.

- ^Andea 2005,pp. 320–321.

- ^abBolovan et al. 1997,p. 166.

- ^abcdefgAndea 2005,p. 321.

- ^Georgescu 1991,p. 56.

- ^Hitchins 2014,p. 44.

- ^Treptow & Popa 1996,p. 212.

- ^Hitchins 2014,pp. 44–45.

- ^Bolovan et al. 1997,p. 169.

- ^abcdeAndea 2005,p. 333.

- ^Georgescu 1991,pp. 61, 65.

- ^abTreptow & Popa 1996,p. 213.

- ^Andea 2005,pp. 337, 339.

- ^George Lupascu Hajdeu:"I, grandson and blood-heir of Prince Stephen Petriceicu, lord of the land of Moldavia, I, unfortunate fugitive from the land of my fathers, I, who was once a wealthy boyar, but who now am a wanderer in a strange land, so poor and poverty-stricken that in my old age I cannot even leave my God alms and a sacrifice, I promise that if God grants that Moldavia, or the district of Hotin, escapes from its enemies, the Turks, and my sons, or my grandsons, or my family regain possession of their estates and their holdings, a church shall be built to St. George in Dolineni (Hotin).... Let us not lose hope that God will pardon us, and that our dear Moldavia shall not always remain under the heel of the Muslims.... May pagan feet not tread on my ancestors' graves, and if my ashes may not rest in my ancestral soil, may my descendants' have that good fortune!"

- ^Gen.Pavel KiseleffRussia on the Danube,p. 211:"The inhabitants fled out of Bessarabia, preferring the Turkish regime, hard though it was, to ours."

- ^abcdefTransylvania under the Habsburgsin U.S. Library of Congress country study on Romania (1989, Edited by Ronald D. Bachman).

- ^abcThe Reign of Joseph IIin U.S. Library of Congress country study on Romania (1989, Edited by Ronald D. Bachman).

- ^With reference to the 1784 revolt, the U.S. Library of Congress country study says "under Ion Ursu". That is presumably "Vasile Ursu", generally known by his nom-de-guerre, Horea. The revolt is generally known to Romanians as the Revolt of Horea, Cloşca and Crişan.

Bibliography[edit]

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.Country Studies.Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.Country Studies.Federal Research Division.

- Andea, Susana (2005). "The Romanian Principalities in the 17th Century". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.).History of Romania: Compendium.Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 315–396.ISBN978-973-7784-12-4.

- Barta, Gábor (1994). "The Emergence of the Principality and its First Crises (1526–1606)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.).History of Transylvania.Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 245–300.ISBN963-05-6703-2.

- Bolovan, Ioan; Constantiniu, Florin; Michelson, Paul E.; Pop, Ioan Aurel; Popa, Cristian; Popa, Marcel; Scurtu, Ioan; Treptow, Kurt W.; Vultur, Marcela; Watts, Larry L. (1997).A History of Romania.The Center for Romanian Studies.ISBN973-98091-0-3.

- Cartledge, Bryan (2011).The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary.C. Hurst & Co.ISBN978-1-84904-112-6.

- Crowe, David M. (2007).A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia.Palgarve.ISBN978-1-4039-8009-0.

- Davies, Norman (1982).God's Playground: A History of Poland, Volume I: The Origins to 1795.Columbia University Press.ISBN0-231-05351-7.

- Dörner, Anton (2009). "Power Structure". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.).The History of Transylvania, Vol. II (From 1541 to 1711).Romanian Academy (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 134–178.ISBN978-973-7784-43-8.

- Dungaciu, Dan; Manolache, Viorella (2019).100 Years since the Great Union of Romania.Cambridge Scholars Publishing.ISBN978-15-27-54297-6.

- Fine, John V. A (1994).The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest.The University of Michigan Press.ISBN0-472-08260-4.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991).The Romanians: A History.Ohio State University Press.ISBN0-8142-0511-9.

- Hitchins, Keith(2014).A Concise History of Romania.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-87238-6.

- Kontler, László (1999).Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary.Atlantisz Publishing House.ISBN963-9165-37-9.

- Makkai, László (1994). "The Emergence of the Estates (1172–1526)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.).History of Transylvania.Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 178–243.ISBN963-05-6703-2.

- Péter, Katalin (1994). "The Golden Age of the Principality (1606–1660)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.).History of Transylvania.Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 245–300.ISBN963-05-6703-2.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1999).Romanians and Romania: A Brief History.Boulder.ISBN0-88033-440-1.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2013)."De manibus Valachorum scismaticorum...": Romanians and Power in the Mediaeval Kingdom of Hungary: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries.Peter Lang Edition.ISBN978-3-631-64866-7.

- Prodan, D. (1971).Supplex Libellus Valachorum or The Political Struggle of the Romamnians in Transylvania during the 18th Century.Publishing House of the Academy of the Socialist Republic of Romania.

- R. Várkonyi, Ágnes (1994). "The End of Turkish Rule in Transylvania and the Reunification of Hungary (1660–1711)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.).History of Transylvania.Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 359–411.ISBN963-05-6703-2.

- Rüsz Fogarasi, Enikő (2009). "Habitat, nutrition, crafts". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.).The History of Transylvania.Vol. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 181–197.ISBN978-973-7784-43-8.

- Stavrianos, L. S. (2000).The Balkans since 1453.Hurst & Company.ISBN978-1-85065-551-0.

- Szegedi, Edit (2009). "The Birth and Evolution of the Principality of Transylvania (1541–1690)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.).The History of Transylvania.Vol. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 99–111.ISBN978-973-7784-43-8.

- Treptow, Kurt W.; Popa, Marcel (1996).Historical Dictionary of Romania.Scarecrow Press, Inc.ISBN0-8108-3179-1.

- Charles Upson Clark:Bessarabia: Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea[1];

- Stanislaw Schwann: Marx-Engels Archives, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, the Netherlands;

- Karl Marx – Însemnări despre români,Ed. Academiei RPR, București, 1964

- Pop, Ioan Aurel,Istoria Transilvaniei medievale: de la etnogeneza românilor până la Mihai Viteazul( "Histori of medieval Transylvania, from the ethno-genesis the Romanians until Mihai Viteazul" ), Cluj-Napoca.

- Iorga Nicolae: "Byzance après Byzance. Continuation de l'" Histoire de la vie Byzantine "", Institut d'Etudes Byzantines, Bucharest 1935;

- Chris Hellier "Monasteries of Greece"; Tauris Editions, London 1995;