Eclogue 6

Eclogue 6(EclogaVI;BucolicaVI) is a pastoral poem by the Latin poetVirgil.In BC 40, a new distribution of lands took place in North Italy, and Alfenus Varus and Cornelius Gallus were appointed to carry it out.[1]At his request that the poet would sing some epic strain, Virgil sent Varus these verses.[1]

The poet speaks as though Varus had urged him to attempt epic poetry and excuses himself from the task, at the same time asking Varus to accept the dedication (line 12) of the pastoral poem which follows, and which relates how two shepherds caughtSilenusand induced him to sing a song containing an account of thecreationand many famous legends.[2]

Context

[edit]

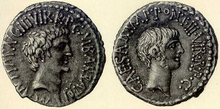

After thePerusine war(41 BC)Pollio,who had beenlegateinTranspadane Gauland aided Virgil to recover his farm (seeEclogue 1), had been superseded, as being a partisan ofAntony,by an adherent ofOctaviancalledAlfenus Varus.[2]This change of circumstances seems to have caused some difficulty to Virgil, and he is said to have nearly lost his life in a contest with Arrius, a centurion, to whom his farm had been assigned.[2]Also, in BC 40, a new distribution of lands took place in North Italy, andAlfenus Varus,with the poetCornelius Gallus,was appointed to carry it out (compareEclogue 9).[1]Varus and his friend Gallus (seeEclogue 10) helped Virgil, who addresses this Eclogue to his patron.[2]

Summary

[edit]The poem may be summarised as follows:[3]

1Virgil begins by explaining that his Muse,Thalea,first deigned to play songs in "Syracusan" verse (i.e. imitating those ofTheocritus,who came fromSyracuse, Sicily); when he attempted to write epic poetry ( "kings and battles" ) Apollo checked him with the words, "Tityrus, a herdsman ought to pasture fat sheep, but sing thin poetry". He says he will therefore leave the task of singing Varus's military exploits to others, but nonetheless wishes to honour Varus by inscribing his name at the top of his poem. No page is more welcome to Apollo than one which is dedicated to Varus.

13He then goes on to tell a story of how two boys, Chromis and Mnasyllus, came across the mythical figureSilenussleeping drunk in a cave and tied him up in his own garlands. Soon they were joined by anaiadcalled Aegle, who playfully painted his forehead with mulberry juice. Then Silenus laughed, and agreed to sing the boys a song; Aegle would have a different reward. When he began to sing,Faunsand wild animals began to play, and oak trees to move their branches.

31Silenus sings how the world began when, in a vast void, the seeds of the Earth, Soul, Sea, and Fire were gathered together; how land and sea separated, things gradually took form, the sun appeared for the first time, rain fell from the sky, woods grew up and wild animals roamed the mountains.

41He then recounts a cycle of the old Greek myths, beginning withPyrrha,who recreated the human race by throwing stones after the Great Flood, theGolden Ageof Saturn,Prometheuswho stole fire and was punished for it in the Caucasus mountains, the boyHylas,who drowned in a pool on the voyage of the Argonauts, andPasiphaë,who fell in love with a bull – a madness worse than that of thedaughters of Proetus,who imagined they were cows; he imagines the lament Pasiphaë sang as she vainly hunted for her bull in the mountain forests of Crete.

61Then he tells the story ofAtalanta,who was defeated in a foot race because she stopped to admire the golden apples of theHesperides;the sisters ofPhaethon,who were turned into poplar trees when mourning for their brother; how the poetGalluswas greeted by theMusesonMount Helicon,where the singerLinuspresented him with the Muses' panpipes and bade him sing of Apollo's sacred grove atGryneiumin Asia Minor.[4]

74Silenus continued with the story ofScylla,[5]whose lower parts consisted of barking dogs, the story of KingTereus,who raped his sister-in-lawPhilomela,and all the other songs which the god Apollo once sang beside the RiverEurotasin mourning for his belovedHyacinthus.

84Silenus continued to sing until evening came and he ordered the sheep to be gathered in to their stables.

Acrostic

[edit]In the introduction to Silenus's song (lines 14–24) Neil Adkin discovered an acrostic, consisting of the wordLAESIS,meaning'for those who have been harmed'.This occurs twice, reading both upwards and downwards from the same letter L in line 19. It is thought that this refers to the landholders in Mantua who had been harmed by Alfenus Varus's land confiscations in 41 BC. Thus although Virgil ostensibly dedicates the poem to Varus, the real dedicatees are the farmers whom Varus forced to leave their lands. The last line of the acrostic (24)solvite me, pueri; satis est potuisse videri'release me, boys; it is enough to be seen to have been able'could also be interpreted as'solve me, boys; it is enough to have been able to be seen',a possible pointer to the presence of the acrostic.[6]The poem also contains praise ofCornelius Gallus,who, apart from his role as a poet, is said to have made a speech criticising Varus for confiscating land right up to the walls of Mantua when he had been ordered to leave a margin of 3 miles.[7]

References

[edit]- ^abcGreenough, ed. 1883, p. 16.

- ^abcdPage, ed. 1898, p. 139.

- ^For a more detailed summary, see Page, T. E. (1898).P. Vergili Maronis: Bucolica et Georgica,pp. 139–147.

- ^This grove was the subject of a poem byEuphorion of Chalcis,which, according to the commentatorServius,was imitated by Gallus. See Dix, T. K. (1995)."Vergil in the Grynean Grove: Two Riddles in the Third Eclogue".Classical Philology,90 (3): 256–262.

- ^Virgil deliberately confuses the sea monster withScylla (daughter of Nisus).

- ^Adkin (2014), pp. 46–47.

- ^Wilkinson, L. P. (1966)."Virgil and the Evictions".Hermes,94(H. 3), 320–324; p. 321.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Adkin, N. (2014)."Read the edge: Acrostics in Virgil's Sinon Episode".Acta Classica Universitatis Scientiarum Debreceniensis.

- Courtney, E. (1990)."Vergil's SixthEclogue".Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica,New Series, Vol. 34, No. 1 (1990), pp. 99–112.

- Elder, J. P. (1961)."Non Iniussa Cano:Virgil's Sixth Eclogue ".Harvard Studies in Classical Philology.65:109–125.doi:10.2307/310834.JSTOR310834.

- Greenough, J. B., ed. (1883).Publi Vergili Maronis: Bucolica. Aeneis. Georgica.The Greater Poems of Virgil. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Ginn, Heath, & Co. pp. 16–18.(public domain)

- Page, T. E., ed. (1898).P. Vergili Maronis: Bucolica et Georgica.Classical Series. London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd. pp. 131–9.(public domain)

- Paschalis, M. (1993)."Two Implicit Myths in Virgil's SixthEclogue".Vergilius (1959–).39:25–29.JSTOR41592488.

- Putnam, Michael C. J. (1970).Virgil's Pastoral Art: Studies in the Eclogues.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 195–221.ISBN978-0-691-06178-8.

- Rutherford, R. B. (1989)."Virgil's Poetic Ambitions inEclogue6 ".Greece & Rome.36(1): 42–50.doi:10.1017/S0017383500029326.JSTOR643184.

- Segal, C. (1969)."Vergil's Sixth Eclogue and the Problem of Evil".Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association.100:407–435.doi:10.2307/2935924.JSTOR2935924.

- Seider, A. M. (2016)."Genre, Gallus, and Goats: Expanding the limits of pastoral in Eclogues 6 and 10".Vergilius(1959-), Vol. 62 (2016), pp. 3-23.

- Wilkinson, L. P. (1966)."Virgil and the Evictions".Hermes,94(H. 3), 320–324.