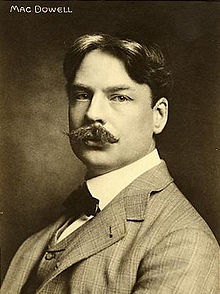

Edward MacDowell

Edward MacDowell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 18, 1860 |

| Died | January 23, 1908(aged 47) New York City |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | List of compositions |

| Spouse | Marian MacDowell |

| Signature | |

Edward Alexander MacDowell(December 18, 1860[1]– January 23, 1908) was an American composer and pianist of the lateRomantic period.He was best known for hissecond piano concertoand his piano suitesWoodland Sketches,Sea PiecesandNew England Idylls.Woodland Sketchesincludes his most popular short piece, "To a Wild Rose".In 1904 he was one of the first seven Americans honored by membership in theAmerican Academy of Arts and Letters.

Studies[edit]

Edward MacDowell was born inNew York Cityto Thomas MacDowell, a Manhattan milk dealer, and Frances “Fanny” Mary Knapp.[2][3]He received his first piano lessons from Juan Buitrago, a Colombianviolinistwho was living with the MacDowell family at the time. He also received music lessons from friends of Buitrago, including the Cuban pianist Pablo Desverine and Venezuelan pianist and composerTeresa Carreño.[4]MacDowell's mother decided to take her son to Paris, France, where in 1877 he was admitted to theParis Conservatoryafter receiving a competitive scholarship for international students.[4]

After two years of studies underAntoine François Marmonteland being at the top of his class, he continued his education atDr. Hoch's ConservatoryinFrankfurt,Germany, where he studied piano withCarl Heymannand composition withJoachim Raff.WhenFranz LisztandClara Schumannvisited the conservatory in early 1880 and attended a recital of student compositions, MacDowell performed Robert Schumann's Quintet, Op. 44 along with a transcription of a Lisztsymphonic poem.Next year, he paid a visit to Liszt inWeimarand performed some of his own compositions. Liszt recommended MacDowell's First Modern Suite, Op. 10 toAllgemeiner Deutscher Musikvereinfor performance and also introduced him to Leipzig music publishers atBreitkopf & Härtel.[4]

After finishing his studies in 1881, MacDowell remained for a while in Germany, where he composed, performed on stage and gave piano lessons.[3]He taught piano at various places inDarmstadtduring 1881–1884, including theSchmitt's Akademie für Tonkunst(now known as theAkademie für Tonkunst), and inWiesbaden,1884–1888.[5]

Marriage and family[edit]

In 1884, MacDowell marriedMarian Griswold Nevins,an American who had been one of his piano students in Frankfurt for three years. About the time that MacDowell composed a piano piece titledCradle Song,Marian suffered an illness that resulted in her being unable to bear children.[6]

Career[edit]

In Germany, the MacDowells settled first in Frankfurt, then inDarmstadt,and finally, inWiesbaden.From 1885 to 1888 MacDowell devoted himself almost exclusively to composition. That brought financial difficulties, and he decided to return to the United States in the autumn of 1888.[7]He madeBostonhis new home, where he became well known as a concert pianist and piano teacher. He performed inrecitalswith theBoston Symphony Orchestraand other American musical organizations.

The MacDowells lived in Boston until 1896, when Edward was appointed professor of music atColumbia University,the first music professor in the university's history. He was personally invited to Columbia University by its presidentSeth Lowto create a music department.[3]He stayed at Columbia until 1904. In addition to composing and teaching, from 1896 to 1898 he directed theMendelssohn Glee Club.MacDowell composed some music for the group to perform.

In 1896, Marian MacDowell purchased Hillcrest Farm, to serve as their summer residence inPeterborough, New Hampshire.MacDowell found his creativity flourished in the beautiful rural setting. His compositions included two piano concertos, two orchestral suites, four symphonic poems, fourpiano sonatas,pianosuites,and songs. He also published dozens of pianotranscriptionsof mostly 18th century pre-piano keyboard pieces.[8]

From 1896 to 1898, MacDowell also published 13 piano pieces and 4part songsunder the pseudonym of Edgar Thorn. These compositions were not mentioned in Lawrence Gilman's 1909 biography of MacDowell. They were listed withoutopus numbersin MacDowell'sCritical and Historical Essays(1912) and in John F. Porte'sEdward MacDowell(1922). They were listed with opus numbers in Oscar Sonneck'sCatalogue of First Editions of Edward MacDowell(1917).

MacDowell was also a noted teacher of the piano and music composition. His students includedJames Dunn,E. Ray Goetz,Frances TarboxandJohn Pierce Langs,a student fromBuffalo, New York,with whom he became very close friends. Langs was also close to noted Canadian pianistHarold Bradley,and both championed MacDowell's piano compositions. The linguistEdward Sapirwas also among his students.[9]

MacDowell was often stressed in his position at Columbia University, due to both administrative duties and growing conflict with the new university presidentNicholas Murray Butleraround a proposed two-course requirement in fine arts for all undergraduate students, as well as creation of combined Department of Fine Arts overseeing music, sculpture, painting and comparative literature.[10]: 243 After Butler stripped the academic affairs voting rights of Columbia faculty members in the arts and accused MacDowell of unprofessional conduct and sloppy teaching, in February 1904, MacDowell abruptly announced his resignation, raising an unfortunate public controversy.[3]

After stepping down from Columbia professorship, MacDowell fell into depression and his health rapidly deteriorated. E. Douglas Bomberger's biography notes that MacDowell suffered fromseasonal affective disorderthroughout his life, and often made decisions with negative implications in the darkest months of the year. Bomberger advances a new theory for the sudden decline of MacDowell's health:bromide poisoning,which was sometimes mistaken forparesisat the time,[11]as was the case with MacDowell's death certificate.[2]Indeed, MacDowell had long suffered from insomnia, and potassium bromide or sodium bromide were the standard treatment for that condition, and in fact were used in many common remedies of the day. MacDowell also was in contact with bromides through his avid hobby of photography.[10]

A 1904 accident in which MacDowell was run over by aHansom cabon Broadway may have contributed to his growing psychiatric disorder and resulting dementia. Of his final years, Lawrence Gilman, a contemporary, described: "His mind became as that of a little child. He sat quietly, day after day, in a chair by a window, smiling patiently from time to time at those about him, turning the pages of a book of fairy tales that seemed to give him a definite pleasure, and greeting with a fugitive gleam of recognition certain of his more intimate friends."[12]

TheMendelssohn Glee Clubraised money to help the MacDowells. Friends launched a public appeal to raise funds for his care; among the signers wereHoratio Parker,Victor Herbert,Arthur Foote,George Whitefield Chadwick,Frederick Converse,Andrew Carnegie,J. P. Morgan,New York MayorSeth Low,and former PresidentGrover Cleveland.

Marian MacDowell cared for her husband to the end of his life. In 1907, the composer and his wife foundedMacDowell (artists' residency and workshop)(formerly known as The MacDowell Colony) by deeding the Hillcrest Farm to the newly established Edward MacDowell Association. MacDowell died in 1908 inNew York Cityand was buried at his beloved Hillcrest Farm.

Legacy and honors[edit]

In 1896,Princeton Universityawarded MacDowell an honorary degree of Doctor of Music. In 1899, he was elected as the president of the Society of American Musicians and Composers (New York).[5]In 1904, he became one of the first seven people chosen for membership in theAmerican Academy of Arts and Letters.After this experience, the MacDowells envisioned establishing a residency for artists near their summer home inPeterborough, New Hampshire.

TheMacDowell (artists' residency and workshop),a multidisciplinary artists' retreat, continued to honor the composer's memory after his death by supporting the work of other artists in an interdisciplinary environment. With time, it created an important part of MacDowell's legacy. Marian MacDowell led the Edward MacDowell Association and Colony for more than 25 years, strengthening its initial endowment by resuming her piano performances and creating a wide circle of donors, especially among women's clubs and musical sororities and around 400MacDowell music clubs.The Edward MacDowell Association backed many American composers, includingAaron Copland,Edgard Varese,Roger Sessions,William Schuman,Walter Piston,Samuel Barber,Elliott Carter,andLeonard Bernstein,in the beginning phases of their careers by awarding them residencies, fellowships, and theEdward MacDowell Medal.Between 1925 and 1956, Copland received a fellowship eight times; in 1961 he was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal, and he served himself for 34 years on the board of Association and Colony.[13]Amy Beachwas at MacDowell on fellowships from its beginning for many summers while she was in her middle to later career.

After his death, MacDowell was considered as a great, internationally known American composer.[14]In 1940, MacDowell was one of five American composers honored in a series of United States postage stamps. The other four composers wereStephen Foster,John Philip Sousa,Victor Herbert,andEthelbert Nevin.However, as the twentieth century progressed, his fame was eclipsed by such American composers asCharles Ives,Aaron Copland,andRoy Harris.In 1950s,Gilbert Chase,an American music historian and critic, wrote, "When Edward MacDowell appeared on the scene, many Americans felt that here at last was 'the great American composer' awaited by the nation. But MacDowell was not a great composer. At his best he was a gifted miniaturist with an individual manner. Creatively, he looked toward the past, not toward the future. He does not mark the beginning of a new epoch in American music, but the closing of a fading era, thefin de siecledecline of the genteel tradition which had dominated American art since the days of Hopkinson and Hewitt. "[15]In the 1970s, John Gillespie reaffirmed Chase's opinion by writing that MacDowell's place in time "accounts for his decreasing popularity; he does not belong with the great Romantics, Schumann and Brahms, but neither can be regarded as a precursor of twentieth century music."[16]Other critics, such asVirgil Thomson,maintained that MacDowell's legacy would be reconsidered and regain a place proper to its significance in the history of American music.[3]

As romantic tradition in music never lost its relevance and importance, the twenty-first century brought a reassessment of MacDowell's legacy not only as a talented piano virtuoso and piano composer, but also as one of America's preeminent composers. On February 14, 2000, he was inducted into a nationalClassical Music Hall of Fame.[13]MacDowell's two concertos are now perceived as the "most important works in the genre by an American composer other than Gershwin."[17]His four sonatas, two orchestral suites and multiple solo piano pieces are performed and recorded.

Works[edit]

The following lists were compiled from information in collections of sheet music, Lawrence Gilman'sEdward MacDowell: A Study(1908), Oscar Sonneck'sCatalogue of First Editions of Edward MacDowell(1917), and John F. Porte'sEdward MacDowell(1922).

Published compositions for piano, a complete listing

- Op. 1Amourette(1896) (as Edgar Thorn)

- Op. 2In Lilting Rhythm(1897) (as Edgar Thorn)

- Op. 4Forgotten Fairy Tales(1897) (as Edgar Thorn)

- Op. 7Six Fancies(1898) (as Edgar Thorn)

- In 1895, an "Op. 8 Waltz" for piano by MacDowell was listed byBreitkopf & Härtel,but no price was shown, and the piece was not published.[18]

- Op. 10First Modern Suite(1883)

- Op. 13Prelude and Fugue(1883)

- Op. 14Second Modern Suite(1883)

- Op. 15Piano Concerto No. 1(1885)

- Op. 16Serenata(1883)

- Op. 17Two Fantastic Pieces(1884)

- Op. 18Two Compositions(1884)

- Op. 19Forest Idylls(1884)

- Op. 20Three Poems(1886) duets

- Op. 21Moon Pictures(1886) duets afterHans Christian Andersen's "Picture-book without Pictures"

- Op. 23Piano Concerto No. 2(1890)

- Op. 24Four Compositions(1887)

- Op. 28Six Idylls after Goethe(1887)

- Op. 31Six Poems after Heine(1887,1901)

- Op. 32Four Little Poems(1888)

- Op. 36Etude de Concert(1889)

- Op. 37Les Orientales(1889)

- Op. 38Marionettes(1888,1901)

- Op. 39Twelve Studies(1890)

- Op. 45Sonata Tragica(1893)

- Op. 46Twelve Virtuoso Studies(1894)

- Op. 49Air and Rigaudon(1894)

- Op. 50Sonata Eroica(1895) "Flos regum Arthurus"

- Op. 51Woodland Sketches(1896) (for Robert La Fosse's ballet, seeWoodland Sketches(ballet))

- Op. 55Sea Pieces(1898)

- Op. 57Third Sonata(1900)

- Op. 59Fourth Sonata(1901)

- Op. 61Fireside Tales(1902)

- Op. 62New England Idylls(1902)

MacDowell published two books ofTechnical Exercisesfor piano; piano duet transcriptions ofHamlet and Opheliafor orchestra (Op. 22);First Suitefor orchestra (Op. 42); and a piano solo version of Op. 42, No. 4,The Shepherdess' Song,renamedThe Song of the Shepherdess.MacDowell composed his First Piano Concerto in the key of A minor in 1885 and published it as his Op.15.[19]It is in three movements:Maestoso-Allegro con fuoco,Andantetranquillo, andPresto

Published compositions for orchestra (complete)

- Op. 15Piano Concerto No. 1(1885)

- Op. 22Hamlet and Ophelia(1885)

- Op. 23Piano Concerto No. 2(1890)

- Op. 25Lancelot and Elaine(1888)

- Op. 29Lamia(1908)

- Op. 30Two Fragments after the Song of Roland(1891) I. The Saracens - II. The Lovely Alda

- Op. 35Romance for Violoncello and Orchestra(1888)

- Op. 42First Suite(1891–1893) I. In a Haunted Forest - II. Summer Idyl - III. In October - IV. The Shepherdess' Song - V. Forest Spirits

- Op. 48Second ( "Indian" ) Suite(1897) I. Legend - II. Love Song - III. In War-time - IV. Dirge - V. Village Festival

Published songs

- Op. 3Love and TimeandThe Rose and the Gardener,for male chorus (1897) (as Edgar Thorn)

- Op. 5The Witch,for male chorus (1898) (as Edgar Thorn)

- Op. 6War Song,for male chorus (1898) (as Edgar Thorn)

- Op. 9Two Old Songs,for voice and piano (1894) I. Deserted - II. Slumber Song

- Op. 11 and 12An Album of Five Songs,for voice and piano (1883) I. My Love and I - II. You Love Me Not - III. In the Skies - IV. Night-Song - V. Bands of Roses

- Op. 26From an Old Garden,for voice and piano (1887) I. The Pansy - II. The Myrtle - III. The Clover - IV. The Yellow Daisy - V. The Blue Bell - VI. The Mignonette

- Op. 27Three Songs,for male chorus (1890) I. In the Starry Sky Above Us - II. Springtime - III. The Fisherboy

- Op. 33Three Songs,for voice and piano (1894) I. Prayer - II. Cradle Hymn - III. Idyl

- Op. 34Two Songs,for voice and piano (1889) I. Menie - II. My Jean

- Op. 40Six Love Songs,for voice and piano (1890) I. Sweet, Blue-eyed Maid - II. Sweetheart, Tell Me - III. Thy Beaming Eyes - IV. For Love's Sweet Sake - V. O Lovely Rose - VI. I Ask but This

- Op. 41Two Songs,for male chorus (1890) I. Cradle Song - II. Dance of the Gnomes

- Op. 43Two Northern Songs,for mixed chorus (1891) I. The Brook - II. Slumber Song

- Op. 44Barcarolle,for mixed chorus with four-hand piano accompaniment (1892)

- Op. 47Eight Songs,for voice and piano (1893) I. The Robin Sings in the Apple Tree - II. Midsummer Lullaby - III. Folk Song - IV. Confidence - V. The West Wind Croons in the Cedar Trees - VI. In the Woods - VII. The Sea - VIII. Through the Meadow

- Two Songs from the Thirteenth Century,for male chorus (1897) I. Winter Wraps his Grimmest Spell - II. As the Gloaming Shadows Creep

- Op. 52Three Choruses,for male voices (1897) I. Hush, hush! - II. From the Sea - III. The Crusaders

- Op. 53Two Choruses,for male voices (1898) I. Bonnie Ann - II. The Collier Lassie

- Op. 54Two Choruses,for male voices (1898) I. A Ballad of Charles the Bold - II. Midsummer Clouds

- Op. 56Four Songs,for voice and piano (1898) I. Long Ago - II. The Swan Bent Low to the Lily - III. A Maid Sings Light - IV. As the Gloaming Shadows Creep

- Op. 58Three Songs,for voice and piano (1899) I. Constancy - II. Sunrise - III. Merry Maiden Spring

- Op. 60Three Songs,for voice and piano (1902) I. Tyrant Love - II. Fair Springtide - III. To the Golden Rod

- Summer Wind,for women's voices (1902)

- Two College Songs,for women's voices (1907) I. Alma Mater - II. At Parting

Selected recordings[edit]

- Piano Concerto No. 2:Van Cliburn,Chicago Symphony Orchestra,Walter Hendl(1960)

- Piano Concerto No. 1andPiano Concerto No. 2:Donna Amato,London Philharmonic Orchestra,Paul Freeman(1985)

- Woodland Sketches, Op.51,Sea Pieces, Op.55, Fireside Tales, Op.61, New England Idyls, Op.62:James Barbagallo(1993)

- Piano Sonata No.4 "Keltic", Op.59, Forgotten Fairytales, Op.4, Six poems after Heine, Op.31, Twelve Virtuoso Studies, Op.46: James Barbagallo

- Étude de Concert, Op.36, Second Modern Suite, Op.14, Serenata, Op.16, Two Fantasy Pieces, Op.17, Twelve Études, Op.39: James Barbagallo

- Piano Music by Edward MacDowell,Sandra Carlock (2005)[20]

- Heroic Tales: Piano Music of Edward MacDowell,Fred Karpoff(2002)

Bibliography[edit]

- Gilman, Lawrence:Edward MacDowell: A Study(New York, 1909; reprint N.Y., 1969).

- Baltzell, W. J. (ed.):Critical and Historical Essays: Lectures Delivered at Columbia University by Edward MacDowell(Boston, 1912).

- Sonneck, Oscar:Catalogue of First Editions of Edward MacDowell(Washington D.C.: Library of Congress, 1917).

- Humiston, W. H.:Edward MacDowell(New York, 1921).

- Porte, John F.:Edward Macdowell: A Great American Tone Poet, His Life and Music(New York, 1922).

- Lowens, Margery Morgan:The New York Years of Edward MacDowell(Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1971).

- Levy, Alan H.:Edward MacDowell, an American Master(Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1998).

- Bomberger, E. Douglas:MacDowell(New York: Oxford University Press, 2013);ISBN9780199899296.

See also[edit]

- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 206:The MacDowell Graves

References[edit]

- ^Until 1975, it was generally accepted that MacDowell's year of birth was 1861. A scholarlyarticleinThe Musical Quarterlycorrected this error.

- ^abRobin Rausch (Music Specialist at the Library of Congress).MacDowell by E. Douglas Bomberger (review).Notes,Volume 71, Number 2, December 2014, pp. 280-283. DOI: 10.1353/not.2014.0150

- ^abcdeAlan Levy.MacDowell, Edward.American National Biography Online.February 2000. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^abcBiography: Edward Alexander MacDowell (1860-1908),Library of Congress

- ^abThe Biographical Dictionary of America,vol. 7, p. 147.

- ^Gilman, Lawrence.Edward MacDowell: A Study.New York, 1909, p. 26.

- ^D. Pesce: "MacDowell, Edward", in:Grove Music Online,ed. Laura Macy. Accessed January 7, 2006.

- ^Baltzell, W. J. (ed.):Critical and Historical Essays: Lectures Delivered at Columbia University by Edward MacDowell(Boston, 1912), pp. 288-289.

- ^Darnell, R. (1990).Edward Sapir: linguist, anthropologist, humanist.University of California press Berkeley & Los Angeles. p. 8.ISBN0-520-06678-2.

- ^abBomberger, E. Douglas:MacDowell(New York: Oxford University Press, 2013);ISBN9780199899296.

- ^J. Madison Taylor, A.M., M.D.Bromide Poisoning Mistaken for Paresis,in:Monthly Cyclopaedia of Practical Medicine,volume 9 (5), May 1906, p. 193-195.

- ^Lawrence Gilman (1909), p. 54.

- ^abEdward Macdowell Inducted Into Classical Music Hall Of Fame,April 28, 2000.

- ^See:Introductory Note by Dr. Allan J Eastman,in:Etude: The Music Magazine,vol. 40, December 1922, p. 817. But see "MacDowell's Protesting Demon," by Edward Robinson, The American Mercury, August 1931, at 500-04 (describing his mental struggles and suggesting they were because he knew his Romantic style 'was a weak refuge in a past and decadent European culture.')

- ^Chase, Gilbert:America's Music, from the Pilgrims to the Present(New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1955), p. 364.

- ^Gillespie, John:Five Centuries of Keyboard Music: An Historical Survey of Music for Harpsichord and Piano(Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Pub. Co.), 1965, p. 313.

- ^Bomberger, E. Douglas:MacDowell's Legacy,Oxford Scholarship Online,May 2015. DOI:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199899296.003.0020

- ^Sonneck, Oscar:Catalogue of First Editions of Edward MacDowell(Library of Congress, 1917), page 9.

- ^"MacDowell, Edward - Piano Concerto No. 1 in A minor Op. 15".Repertoire Explorer.Musikproduktion Höflich.RetrievedMarch 26,2022.

- ^Piano Music by Edward MacDowell – Sandra Carlock

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Gilman, D. C.;Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905)."MacDowell, Edward Alexander".New International Encyclopedia.Vol. XII (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 608.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Gilman, D. C.;Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905)."MacDowell, Edward Alexander".New International Encyclopedia.Vol. XII (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 608.

External links[edit]

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |

- Works by Edward MacDowellatProject Gutenberg

- Edward MacDowell by John F. PorteatProject Gutenbergonline book

- Edward MacDowell by Lawrence GilmanatProject Gutenbergonline book

- Works by or about Edward MacDowellatInternet Archive

- Oscar Sonneck,Catalogue of First Editions of Edward MacDowell(Library of Congress, 1917)online book

- Art of the States: Edward MacDowell

- Free scores by Edward MacDowellat theInternational Music Score Library Project(IMSLP)

- A Tribute to Edward MacDowell on American Music Preservation

- "To a Wild Rose"free PDF and MIDI

- "To a Wild Rose"onYouTube

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 23on YouTube, Thomas Pandolfi

- Polonaise, Op. 46 no. 12 by Edward MacDowellon YouTube

- Sheet music for "To a Wild Rose",A.P. Schmidt Company, 1919

- Sheet music for"Sea Pieces",Boston: Arthur P. Schmidt Co, 1898. FromWade Hall Sheet Music Collection

- Finding aid to Edward MacDowell papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Edward MacDowell recordingsat theDiscography of American Historical Recordings.

- American Piano Music: Edward MacDowell

- 1860 births

- 1908 deaths

- 19th-century American composers

- 19th-century classical composers

- 19th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American composers

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century classical composers

- American expatriates in France

- American expatriates in Germany

- American male classical composers

- American Romantic composers

- Classical musicians from New York (state)

- Columbia University faculty

- Composers for piano

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- Hoch Conservatory alumni

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Composers from New York City

- People from Peterborough, New Hampshire

- Pseudonyms