Einkorn wheat

| Einkorn wheat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Triticum |

| Species: | T. monococcum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Triticum monococcum | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Triticum monococcumsubsp.monococcum | |

| Wild einkorn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Triticum |

| Species: | T. boeoticum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Triticum boeoticum | |

| Synonyms | |

Einkorn wheat(from GermanEinkorn,literally "single grain" ) can refer either to a wild species ofwheat(Triticum) or to itsdomesticated form.The wild form isT. boeoticum(syn.T. m.subsp.boeoticum), and the domesticated form isT. monococcum(syn.T. m.subsp.monococcum). Einkorn is adiploidspecies (2n= 14 chromosomes) of hulled wheat, with toughglumes('husks') that tightly enclose thegrains.The cultivated form is similar to the wild, except that theear stays intact when ripe[1]and the seeds are larger. The domestic form is known as "petit épeautre" in French, "Einkorn" in German, "einkorn" or "littlespelt" in English, "piccolo farro" in Italian and "escanda menor" in Spanish.[2]The name refers to the fact that eachspikeletcontains only one grain.

Einkorn wheat was one of the first plants to bedomesticatedandcultivated.The earliest clear evidence of the domestication of einkorn dates from 10,600 to 9,900 yearsbefore present(8650 BCE to 7950 BCE) fromÇayönüandCafer Höyük,two EarlyPre-Pottery Neolithic Barchaeological sites in southernTurkey.[3]Remnants of einkorn were found with the iceman mummyÖtzi,dated the late 4th millenium BCE.[4]

History[edit]

Einkorn wheat commonly grows wild in the hill country in the northern part of theFertile CrescentandAnatoliaalthough it has a wider distribution reaching into theBalkansand south toJordannear theDead Sea.It is a short variety of wild wheat, usually less than 70 centimetres (28 in) tall and is not very productive of edible seeds.[citation needed]

The principal difference between wild einkorn and cultivated einkorn is the method of seed dispersal. In the wild variety the seed head usually shatters and drops the kernels (seeds) of wheat onto the ground.[1]This facilitates a new crop of wheat. In the domestic variety, the seed head remains intact. While such amutationmay occasionally occur in the wild, it is not viable there in the long term: the intact seed head will only drop to the ground when the stalk rots, and the kernels will not scatter but form a tight clump which inhibits germination and makes the mutant seedlings susceptible to disease. But harvesting einkorn with intact seed heads was easier for early human harvesters, who could then manually break apart the seed heads and scatter any kernels not eaten. Over time and through selection, conscious or unconscious, the human preference for intact seed heads created the domestic variety, which also has slightly larger kernels than wild einkorn. Domesticated einkorn thus requires human planting and harvesting for its continuing existence.[5]This process of domestication might have taken only 20 to 200 years with the end product a wheat easier for humans to harvest.[6]

Einkorn wheat is one of theearliest cultivated formsof wheat, alongsideemmerwheat (T. dicoccum). Hunter gatherers in theFertile Crescentmay have started harvesting einkorn as early as 30,000 years ago, according to archaeological evidence fromSyria.[7][8][9]Although gathered from the wild for thousands of years, einkorn wheat was first domesticated approximately 10,000 years BP in thePre-Pottery Neolithic A(PPNA) orB(PPNB) periods.[10]Evidence fromDNA fingerprintingsuggests einkorn was first domesticated nearKaraca Dağin southeast Turkey, an area in which a number of PPNB farming villages have been found.[11]One theory byYuval Noah Hararisuggests that the domestication of einkorn was linked to intensive agriculture to support the nearbyGöbekli Tepesite.[12]

An important characteristic facilitating the domestication of einkorn and other annual grains is that the plants are largely self-pollinating. Thus, the desirable (for human management) traits of einkorn could be perpetuated at less risk of cross-fertilization with wild plants which might have traits – e.g. smaller seeds, shattering seed heads,[1]as less desirable for human management.[13]

From the northern part of the Fertile Crescent, the cultivation of einkorn wheat spread to theCaucasus,the Balkans, and central Europe. Einkorn wheat was more commonly grown in cooler climates thanemmer wheat,the other domesticated wheat. Cultivation of einkorn in the Middle East began to decline in favor of emmer wheat around 2000 BC. Cultivation of einkorn was never extensive inItaly,southernFrance,andSpain.Einkorn continued to be cultivated in some areas of northern Europe throughout theMiddle Agesand until the early part of the 20th century.[14]

Taxonomy[edit]

- Triticum boeoticum

- syn.Triticum monococcumsubsp.boeoticum(wild)

- Triticum monococcum

- syn.T. monococcumsubsp.monococcum(domesticated)

Einkorn vs. common modern wheat varieties[edit]

Einkorn wheat is low-yielding but can survive on poor, dry, marginal soils where other varieties of wheat will not. It is primarily eaten boiled in whole grains or in porridge.[14]As with other ancient varieties of wheat, Einkorn is grouped with "the covered wheats" as its kernels do not break free from its seed coat (glume) with threshing and it is, therefore, difficult to separate the husk from the seed.[15]

Current use[edit]

Einkorn is a common food in northernProvence(France).[16]It is also used forbulguror asanimal feedin mountainous areas ofFrance,India,Italy,Morocco,theformer Yugoslavia,Turkey,and other countries.[15]

Nutrition and gluten[edit]

Einkorn containsglutenand has a higher percentage of protein than modern red wheats and is considered more nutritious because it has higher levels offat,phosphorus,potassium,pyridoxine,andbeta-carotene.[15]

Genetics[edit]

Disease resistance[edit]

Einkorn is the source of many potential introgressions for immunity –Nikolai Vavilovcalled it an "accumulator of complex immunities."[17]T. monococcumis the source ofSr21,astem rust resistance genewhich has beenintrogressedintohexaploidworldwide.[18]It is also the source ofYr34,aresistance geneforyellow rust.[19]

Salt-tolerance gene[edit]

The salt-tolerance feature ofT. monococcumhas been bred intodurumwheat.[20]

Images[edit]

-

Wild einkorn,Mount Karadağ

-

Associations of wild cereals and other wild grasses in northern Israel

-

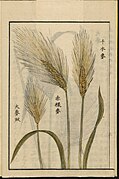

T. monococcum,Japanese agricultural encyclopediaSeikei Zusetsu(1804)

References[edit]

- ^abcBrown, Terence; Jones, Martin; Powell, Wayne; Allaby, Robin (2009)."The complex origins of domesticated crops in the Fertile Crescent"(PDF).Trends in Ecology & Evolution(Review).24(2). Cell Press: 103–109.Bibcode:2009TEcoE..24..103B.doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.008.ISSN0169-5347.PMID19100651.

- ^Le Brun, Alain (1992)."El poblamiento neolítico en la Isla de Chipre: el establecimiento de Khirokitia".Treballs d'Arqueologia(2): 51–67.ISSN1134-9263.Centre national de la recherche scientifique(França).

- ^Weiss, Ehud; Zohary, Daniel (October 2011). "The Neolithic Southwest Asian Founder Crops: Their Biology and Archaeobotany".Current Anthropology.52(S4): S239–S240.doi:10.1086/658367.S2CID83924400– viaJSTOR.

- ^"5,300 Years Ago, Ötzi t'he Iceman Died. Now We Know His Last Meal".Science & Innovation.National Geographic.2018-07-12. Archived fromthe originalon July 13, 2018.Retrieved2019-07-31.

- ^Weiss and Zohary, p. S239-S242

- ^Anderson, Patricia C. (1991). "Harvesting of Wild Cereals During the Natufian as seen from Experimental Cultivation and Harvest of Wild Einkorn Wheat and Microwear Analysis of Stone Tools". In Bar-Yosef, Ofer (ed.).Natufian Culture in the Levant.International Monographs in Prehistory. Ann Arbor, Michigan, US: Berghahn Books. p. 523.

- ^Arranz-Otaegui, A., Carretero, L. G., Ramsey, M. N., Fuller, D. Q., & Richter, T. (2018). "Archaeobotanical evidence reveals the origins of bread 14,400 years ago in northeastern Jordan."Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.doi:10.1073/pnas.1801071115

- ^"Crops evolving ten millennia before experts thought".ScienceDaily.23 October 2017.Retrieved23 October2017.

- ^Allaby, Robin; Stevens, Chris; Lucas, Leilani; Maeda, Osamu; Fuller, Dorian (Oct 2017)."Geographic mosaics and changing rates of cereal domestication".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.372(1735).The Royal Society:20160429.doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0429.PMC5665816.PMID29061901.

- ^Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria; Weiss, Ehud (2012).Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin(Fourth ed.).Oxford University Press(OUP). p. 38.ISBN9780199549061.

- ^Heun, M.; Schäfer-Pregl, R.; Klawan, D.; Castagna, R.; Accerbi, M.; Borghi, B.; Salamini, F. (1997). "Site of Einkorn Wheat Domestication Identified by DNA Fingerprinting".Science.278(5341): 1312–1314.Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1312H.doi:10.1126/science.278.5341.1312.

- ^Harari, Yuval N.; Watzman, Haim (10 February 2015).Sapiens: a brief history of humankind.Translated by Purcell, John (First U.S. ed.). New York: Harper.ISBN978-0-06-231609-7.OCLC896791508.

- ^Bellwood, Peter (2005).First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies.Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 46-49.

- ^abHopf, M.; Zohary, Daniel (2000).Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley(3rd ed.). Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. pp. 33–43.ISBN0-19-850356-3.

- ^abcStallknecht, G. F., Gilbertson, K. M., and Ranney, J.E. (1996), "Alternative Wheat Cereals as Food Grains: Einkorn, Emmer, Spelt, Kamut, and Triticale" in J. Janick, ed.,Progress in New Crops,Alexandria, VA: ASHA Press, pp. 156-170

- ^Payany, E (2011).Le Petit Épeautre.LaPlage.ISBN978-2-84221-283-4.

- ^Zaharieva, Maria; Monneveux, Philippe (2014). "Cultivated einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcumL. subsp.monococcum): the long life of a founder crop of agriculture ".Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution.61(3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 677–706.doi:10.1007/s10722-014-0084-7.eISSN1573-5109.ISSN0925-9864.S2CID16551824.

- ^Roelfs, Alan P.; Singh, R. P.; Saari, E. E. (1992).Rust diseases of wheat: concepts and methods of disease management.Mexico, D.F:CIMMYT(International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center). p. 81.ISBN968-6127-47-X.OCLC26827677.

- ^Baranwal, Deepak (2022)."Genetic and genomic approaches for breeding rust resistance in wheat".Euphytica.218(11).doi:10.1007/s10681-022-03111-y.S2CID252973250.

- ^"World Breakthrough On Salt-Tolerant Wheat".ScienceDaily. March 11, 2012.